Improving Systems of Follow-Up Care for Traumatic Brain Injury: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 2 Action Collaborative on Traumatic Brain Injury Care

The first session of the workshop featured reports from the working groups that are part of the forum’s Action Collaborative on Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) Care and described the groups’ progress and next steps. Forum members recently launched this Action Collaborative to advance care for community-acquired TBI, with an initial focus on follow-up care for adult TBI at the milder end of the severity spectrum, a key issue also addressed by this workshop.

INTRODUCTION TO THE ACTION COLLABORATIVE ON TBI CARE

Geoffrey Manley, professor and vice chair of neurological surgery, University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) and chief of neurosurgery, Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital, highlighted several current gaps in TBI research and follow-up care and introduced the goals of the

Action Collaborative. It has been reported that a majority of individuals with mild TBI receive little to no follow-up care (Seabury et al., 2018). Individuals who have the capacity to recover may experience disability instead, he said, because of the false assumption that this lack of follow-up care is related to an absence of post-TBI symptoms. In the absence of disease-modifying drugs for TBI, treatments to manage and address the various symptoms a person may experience after TBI can improve their quality of life. The research community has made substantial efforts to understand the TBI care needs of the sports and military communities, and of individuals with moderate and severe TBI, but less is known about the care needs associated with recovery following the often inaptly characterized “mild” TBI, in community-acquired settings, meaning TBI associated with accidents affecting community members. As a result, the Action Collaborative seeks to gather input on essential components for improved care systems for community-acquired TBI, with a focus on follow-up care in the first year postinjury, clinical guidance on symptom management aimed at outpatient TBI programs and primary care providers, and enhanced TBI education, discharge, and ongoing care instructions. The Action Collaborative has established several working groups to make progress in these areas, and these working groups also maintain regular communication and coordination to stay aligned in their efforts.

Manley emphasized the importance of incorporating patient and family input when addressing gaps in TBI management and care. He noted that as many as 50 percent of adult TBI patients with injuries at the milder end of the spectrum receive no discharge instructions, and many patients and families are not even aware of their TBI diagnosis after receiving emergency department (ED) treatment. Furthermore, the majority of practitioners in the health care community are unaware of the long-term consequences of TBI in patients who have Glasgow Coma Scale scores in the mild range of 13 to 15, approximately half of whom will not have fully recovered at 12 months postinjury (Nelson et al., 2019). Providers often tell ED patients with a mild TBI that a normal computed tomography (CT) scan signifies that their symptoms should disappear within a few days, Manley said; individuals are thus undereducated and unprepared when they experience persistent symptoms. To advance efforts to better address the needs of the 5 million individuals who seek ED care for TBI each year, Manley ended with a call to develop and scale a demonstration project incorporating key elements for improved post-TBI care and education, informed by the Action Collaborative working groups and other efforts.

REFLECTIONS FROM ACTION COLLABORATIVE WORKING GROUPS

Clinical Practice Guidelines

Kathy Lee, director of Department of Defense Warfighter Brain Health Policy, Office of the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Readiness Policy and Oversight, highlighted the Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPG) working group’s objective of enhancing support for community-based health professionals through evidence-based clinical management recommendations for optimizing the recovery and wellness of people with TBI. The working group has drafted a scope statement to inform the creation of guidance based on such recommendations. Although this scope statement is not yet finalized, the objective of a guideline or other clinical guidance in this area is to improve postacute clinical management of two groups of adults with TBI: those who can care for themselves at discharge from acute care and those who do not require acute hospital care. The intended CPG would provide a set of priority recommendations for health professionals in primary care community settings, including guidance on referral thresholds for specialty care. This proposed CPG would not address prehospital or hospital-based care, nor would it include recommendations to medical or allied health professionals in specialty care settings. Lee emphasized that this scope would continue to evolve through working group discussions, as appropriate.

The working group has identified 17 existing TBI CPGs that have been published or updated within the last 10 years as a foundation that may be built upon. Currently, the working group is mapping the overlap of these guidelines in such areas as early patient and family education and the timing and frequency of follow-up visits. Lee noted that many current CPGs are focused on the acute management of TBI and on specific subgroups of TBI patients, such as military and sports communities and those with severe TBI. She also noted that existing CPGs tend to be impractically lengthy, spanning more than 50 recommendations. The working group seeks to build on the existing base to create a targeted CPG or other form of guidance focusing on the 10 most effective actions clinicians can take, targeted to the weeks and months following a TBI diagnosis and with a focus on priorities identified by TBI patients, their families, and primary care providers (PCPs). Moving forward, the working group plans to (1) finish mapping the overlapping areas in existing CPGs and identify any areas not addressed, (2) use patient and provider input to prioritize areas to include in the anticipated new CPG, (3) identify actionable clinical recommendations, and (4) synthesize and coordinate with other Action Collaborative working groups to ensure coherence, standardization, and effect before wider dissemination.

TBI Education and Discharge Instructions

Matthew Breiding, acting deputy associate director of science in the Division of Violence Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), reported that the TBI Education and Discharge Instructions working group is striving to improve the educational materials provided to patients after a TBI. After identifying gaps within example discharge and education materials collected by members of the Action Collaborative, the working group is currently modifying existing materials and developing new ones to fill these gaps. Materials developed by the CDC Heads Up pediatric education initiative are a primary resource in this effort.1 These materials include discharge instructions, symptom-based recovery tips, and a school-based accommodations letter. Research indicates that the number of accommodations provided to students increases when accommodations letters such as the one created by CDC are used, added Breiding. Because the Heads Up materials focus primarily on the needs of children and youth, the working group is creating similar resources tailored to adults with TBI, including return-to-work instructions. The aim is for the materials to be further refined and ultimately made available through the CDC website. Incorporating input from the CDC National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, the working group is developing information for two sets of materials that patients could provide to employers. The first document outlines instructions and accommodations specific to the needs of people who have experienced TBIs but who, in the interest of privacy, do not wish to disclose their TBI diagnosis to an employer; it does not explicitly mention TBI. A second document contains TBI-relevant information that employees could choose to provide to their places of work.

The next steps for the working group entail soliciting feedback on these materials from the Action Collaborative, forum members, and others, creating user-friendly and attractive designs for the content, and developing videos and materials with embedded quick response (QR) codes. The group is also considering how to address additional gaps in patient education beyond return-to-work content. For instance, older adults—who face an increased risk of TBI associated with falls—could benefit from patient education materials that focus on reducing their fall risk and the balance-disturbing effects of some medications. The working group is also discussing methods of improving the dissemination of TBI education materials, such as integration into electronic health records (EHRs). Health care provider education is another key area identified by the group and recent National Academies report (NASEM, 2022); CDC has made progress in

___________________

1 More information about the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Heads Up resources and tools is available at https://www.cdc.gov/headsup/index.html (accessed June 8, 2023).

pediatric TBI education, but efforts are needed to expand provider education related to adult TBI.

Odette Harris, Paralyzed Veterans of America Professor of Spinal Cord Injury Medicine, and director of Brain Injury, Department of Neurosurgery at Stanford University School of Medicine and deputy chief of staff, Rehabilitation at the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System, added that the working group is focused on creating standardized resources that can be continuously updated in a sustainable way. This focus served as the impetus for building on existing materials rather than creating entirely novel resources. Harris and Breiding noted an ongoing discussion about whether mild TBI, TBI, or concussion is the most appropriate term for care providers to use with patients. The group has not reached agreement as to which term is most effective, accurate, and optimally lends itself to dissemination. To inform its work, the working group aims to enlist patients to test draft materials and provide feedback on terminology preferences and on the helpfulness and relatability of the resources.

Follow-Up Care After TBI

Flora Hammond, professor and chair of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation at Indiana University School of Medicine and the chief of medical affairs and brain injury co-medical director at the Rehabilitation Hospital of Indiana, reiterated the observation that despite many individuals experiencing symptoms for months or years post-TBI, fewer than half of all patients receive any form of follow-up care (Seabury et al., 2018). The Follow-Up Care After TBI working group is striving to identify core elements of a best-practice model for postacute clinical TBI care. The group’s discussions have included optimizing patient care flow by identifying points of entry into the follow-up care system and identifying mechanisms to connect patients to needed care. For instance, patients could be directed to an online portal that would guide their care along established pathways and measure their outcomes. Additionally, in a best-practice TBI model, multidisciplinary care is needed to facilitate patient progress, establish access, and provide specialized care when needed. Such a model entails considering patient volume and referral processes, as well as practices and strategies for operational resourcing and establishing return on investment. Furthermore, the creation of a learning health system for TBI would enable the collection of data records to build the evidence base aimed at improvements in care and care practices, thus facilitating the identification of steps that lead to best outcomes for patients. Hammond highlighted the guiding challenge of designing care solutions that are both individualized and scalable.

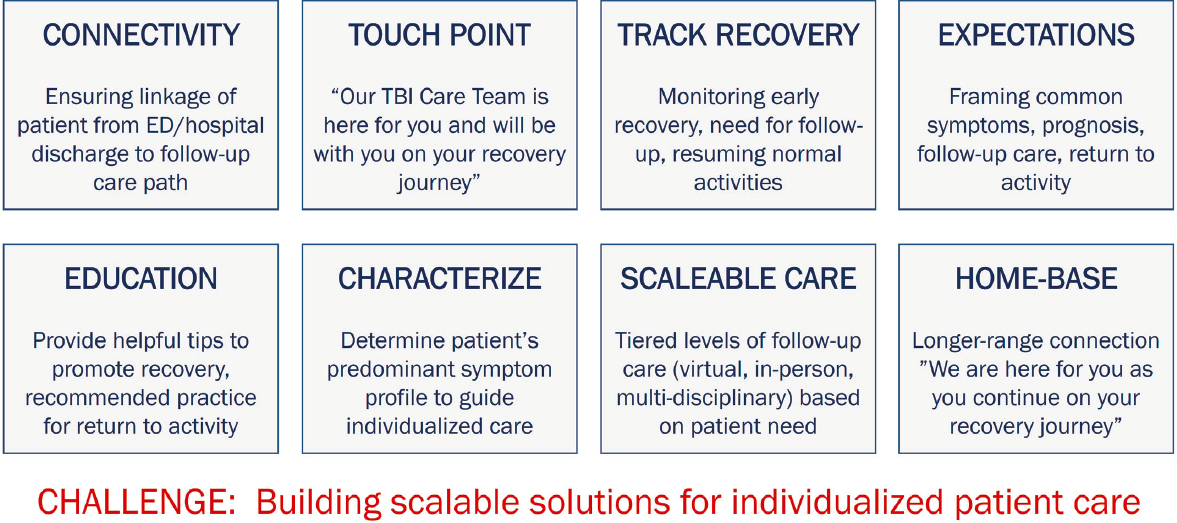

The working group has identified eight multidimensional goals for a TBI follow-up care system (see Figure 2-1). Connectivity involves ensur-

SOURCE: Presented by Flora Hammond, Indiana University School of Medicine, May 9, 2023; Michael McCrea, Medical College of Wisconsin.

ing that medical personnel link patients with the defined path of care before discharge. A touch point conveys to patients that they will have ongoing support throughout their recovery process. Recovery tracking monitors symptoms and determines when individuals require additional care. Expectation setting includes framing common symptoms and providing information on prognosis and follow-up care. Education involves providing tips to promote recovery and recommended practices when returning to activities. Characterizing a patient’s predominant symptom profile guides individualized care. Scalable care includes tiered levels of follow-up care that could be accessed according to patient need. Home base provides a mechanism for longer-term connection throughout a patient’s recovery process.

Designing a Learning Health Care System for TBI Care

Adam Barde, senior principal, and Glen Jacques, managing director, at Slalom Consulting, described a learning health care system (LHS) app their company is developing in conjunction with members of the LHS working group and Amazon Web Services (AWS) to meet the goal of reimagining well-connected postacute TBI care that continuously captures data to improve systems of care. To obtain TBI patient input in the design process, the group interviewed TBI survivors. Jacques noted that patients routinely commented about the lack of education they received but often recounted feeling confused and overwhelmed at hospital discharge, indicating that discharge may be an inopportune time for medical providers to offer detailed education and follow-up instructions. As Barde and Jacques noted, one TBI survivor who participated in focus group discussions commented,

I was struggling with communicating and focusing for more than a few seconds, and they sent me home with a 20-page packet. The whole [discharge] process was overwhelming; it was not easy to understand in a concussed state.

Although TBI patients are stable at the point of discharge, their recovery journey is only beginning, said Jacques. To create a recovery process that helps patients return to baseline more effectively, the working group partnered with Slalom Consulting and AWS to use a “design thinking” process to better understand TBI patient needs and how to meet them. This design thinking process guided the group through the steps of discerning the challenges to address, defining users and stakeholders, interviewing patients to develop a deep understanding and empathy, and generating innovative solutions. The process produced a patient journey map that describes the desired experience, and in turn enabled specification of technical require-

ments and initial design for a pilot digital app that patients could use throughout their recovery.

Barde demonstrated the experience of using the pilot approach and app under development. At discharge, he said, TBI patients would be given a simple document directing them to the app’s website or would be assisted by medical personnel to add it to a mobile device. During onboarding, patients (or their proxy) would create an account using a one-time text for identity verification in lieu of creating a password, thus relieving the patient of the need to remember a password during her state of recovery. Next, the app would provide a description of what to expect during the first few days postdischarge. Upon onboarding, patients would be immediately able to access educational content and resources—including short videos and guided meditations—curated to their unique circumstances. On days 4, 9, 14, and 28 after the injury, the app would prompt patients track and report their symptoms through a user interface designed to simplify the input process. The patients would see their symptoms and severity graphed over time. Based on their responses, the app may advise a patient to seek immediate care at an ED or follow-up care from a PCP or specialist to address post-TBI sequelae, ideally enabling a quicker return to baseline functioning and wellness.

The working group envisions the pilot app and other tools as part of a LHS that continuously improves the patient experience by using data analytics and ongoing learning, said Barde. Various levels of EHR integration will be key for clinician workflow, he added. In its prototype form, the app enables patient engagement and system tracking. In the future, the app could also be designed to automatically collect patient data directly from wearable devices. Researchers may be able to access such datasets to gain a deeper understanding of patients, improve care practices, and foster population health, Barde concluded.

Patient Perspectives

Scott Hamilton, an entrepreneur and TBI survivor, reported on the qualitative research he and colleagues conducted under the Patient Perspectives working group, focused on learning by listening. Four TBI consumer focus groups of eight participants each were held in Pittsburgh and Milwaukee.2 All participants had been diagnosed with TBI within the year prior and most were diagnosed with TBI on the milder end of the spectrum, although some

___________________

2 A white paper authored by Scott W. Hamilton and Alan Hamilton describing the focus group process and presenting themes that emerged is available at https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/05-09-2023/improving-systems-of-follow-up-care-for-traumatic-brain-injury-a-workshop (accessed July 26, 2023).

had experienced multiple TBIs. A number of themes emerged across these four focus groups. For example, many patients expressed that medical professionals who made their TBI diagnosis tended to downplay or minimize the consequences of the injury and, in some cases, did not explicitly state the TBI diagnosis. As reported by Hamilton, a 37-year-old woman said,

I wasn’t even told I had a concussion. I found out by looking at my paperwork from the ED visit. And then they didn’t give me any advice on what to do. I just started looking it up on the internet. I never had follow-up on anything.

Stigma was frequently cited by participants, many of whom did not feel comfortable discussing their TBI with others. One focus group member said, “I’m not gonna go advertising to everybody that I’ve had a brain injury.” Another remarked, “It’s frustrating, but I don’t want anyone to realize what I’m going through. I try to hide it as much as I possibly can. It’s a stigma.” Hamilton emphasized that stigma was even felt with medical professionals, as participants described feeling that their ongoing symptoms were minimized and not taken seriously. This sense of stigma can lead to isolation when TBI survivors feel they cannot talk to others about their experiences, he said. Many focus group participants reported feeling alone, regardless of whether they lived on their own or with family. They indicated a need for practical and psychological support and advocacy, remarking about craving a caring, sympathetic person who understood their needs. This sense of isolation appeared to be heightened by the burden they felt their needs placed on others.

Furthermore, focus group participants did not understand the plasticity of the brain and how to facilitate their healing, said Hamilton. People expressed accepting the “new normal” of their limitations, not recognizing that neuroplasticity may generate improved functioning. He cited his own TBI trajectory as an example of recovery, albeit one that lasted a decade. Returning to preinjury functioning is possible, he said, but it may require treatment and patience. Many participants indicated an eagerness for self-help activities, but lacked information on steps they could take to hasten healing. One 48-year-old man remarked,

Tell us more stuff that you can do for self-care. I hate Brussels sprouts, but if someone said that eating Brussels sprouts would make my brain back to the way it used to be, I’m like, oh boy!

Hamilton noted a tendency within the medical community to hold off on making recommendations until multiple randomized controlled trials indicate an intervention is effective. However, patient focus group partici-

pants indicated frustration, helplessness, and powerlessness in the absence of steps they could take to improve their health. If a measure shows indications that it could improve TBI outcomes and is not associated with clear negative effects, he suggested that it should not be withheld from TBI patients pending establishment of a more definitive evidence base.

Many participants also described experiencing psychological trauma during their injuries that had not been sufficiently addressed, Hamilton added. In addition to the trauma to their brains, some group members referred to the experience of living with long-term, untreated symptoms as traumatic. A 24-year-old male participant commented,

This is all traumatic because we’re dealing with this stuff to this day. Short term … we were throwing up and having nausea. The long term is right now: memory issues, remembering things, mumbling, ringing in the ears.

Another remarked, “I feel like all of us, all eight of us, have trauma from this.” A range of treatment options is available to help address symptoms from brain trauma, but most of the participants had not been referred for such interventions. Hamilton emphasized that among the 32 total participants, the best reports of postacute care and education came from participants who had been recruited into a study conducted by the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. A 60-year-old male reflected:

The treatment was spot on. They didn’t rush me, and they said, “This is what you’re gonna see. This is what you’re gonna feel. You can’t drive for a month. You can’t work for a month. Here’s who you follow up with, and this is when we want you to follow up.” You know, they called me to make sure I was gonna make the appointments.

Hamilton contended that all TBI patients should be able to receive this level of care and education.

Implications for Postacute TBI Care

Five components emerged from patient focus group feedback that should be considered in the creation of a TBI postacute care model, said Hamilton. First, the care model should encourage attention to the person’s TBI through possible actions such as increasing the use of objective measures, including biomarkers to confirm diagnosis; requiring doctors to explicitly inform patients of their TBI diagnosis; and shifting terminology from concussion to traumatic brain injury to adequately convey the serious nature of the injury. Second, medical professionals should describe brain health and plasticity to patients in layman’s terms. Given that between

5 and 6 million people experience TBI annually, this education could generate ripple effects and increase the odds that a person who experiences a TBI will receive sound advice about seeking medical care. Third, medical professionals should support patient resilience and empower patients by teaching them steps they can take to promote healing. Research indicates that people having higher resilience (based on measures of this characteristic) have an improved recovery prognosis (Merritt et al., 2015). Patient focus group members reported benefiting from hearing the stories of how other people were contending with and addressing similar challenges, which contributed to their resilience. Fourth, medical professionals should link patients with support and advocacy communities to reduce feelings of isolation. Fifth, the medical community should encourage screening for treatment of psychological trauma after injury. Referring to a popular weight loss app that uses a psychological approach, Hamilton noted that focus group participants expressed a desire for similar tools that could support their personal post-TBI care and recovery needs.

DISCUSSION

Amy Markowitz, program manager for the Traumatic Brain Injury Endpoints Development Initiative at San Francisco General Hospital, served as moderator and began the discussion by posing an opening question on dissemination and implementation of the proposed clinical guidance for post-TBI management described by members of the Action Collaborative. Subsequent topics arose in response to comments and questions from participants.

Clinical Practice Guideline Implementation

The first topic addressed was on strategies to expedite dissemination and implementation of clinical guidance for post-TBI management, while attending to the varied settings in which patients may access care, including the ED, PCP offices, and community practice settings. Lee highlighted policy as one of the most influential mechanisms for changing care standards within the military, although she noted that policy directives operate differently within the civilian sector. Policy compliance can be evaluated using established metrics, she said. Didactic, multidisciplinary training events are also a vehicle for educating practitioners on the use of effective tools. Additionally, using word-of-mouth to generate awareness around the ease and effectiveness of implementing guidance on TBI management could create culture shifts that hasten adoption of new guidelines. David Okonkwo, professor and director, Neurotrauma Clinical Trials Center, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, remarked that the equivalent

of military policy in the civilian sector is payment and insurance coverage. Establishing appropriate reimbursement for the implementation of a guideline that affects clinical care facilitates the speed of adoption, he said. Harris added that linking a CPG to accreditation can be an effective strategy that simultaneously ties it to the motivation of payment.

Pediatric TBI Population

Flaura Winston, professor of pediatrics, University of Pennsylvania and scientific director of the Center for Injury Research and Prevention, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), noted the absence of children in the Action Collaborative working group reports. Markowitz replied that adult care is the chosen starting point for this particular set of efforts, and that levels of TBI follow-up care may sometimes be lower for adults than for children. Manley highlighted the work CDC has contributed to the awareness of pediatric TBI via the Heads Up education initiative previously mentioned. The Action Collaborative may incorporate a focus on children after addressing the current gap in adult TBI care, he said. Christina Master, professor of clinical pediatrics, University of Pennsylvania and codirector, Minds Matter Concussion Program, CHOP, added that parallel pediatric work is in development through her organization and others, and these efforts can synergize with the Action Collaborative work focused on adults. In the future, Manley said that the Action Collaborative also plans to consider the specific needs of adults over age 65, who constitute an important part and the fastest growing proportion of the population that sustains a TBI.

Data Gaps in Understanding Which Patients Will Need Follow-Up Care and Potential Effects on Capacity

Ramon Diaz-Arrastia, John McCrea Dickson, MD Professor of Neurology and director, Clinical TBI Research Center at the University of Pennsylvania, noted that the vast majority of the 5 to 6 million people who suffer a mild TBI annually will recover, and he remarked on the potential risk of overmedicalizing the condition. He added that the participants in the study he coauthored, which found that half of the patients who visited the ED for mild TBI had not recovered within 12 months, were patients at a Level 1 trauma center who consented to participate in a study and follow-up visits (Nelson et al., 2019); it is possible results could differ for other TBI patient populations. Prognostic tools are needed to differentiate between the 15–20 percent of mild TBI patients who will experience long-term symptoms and the 80–85 percent who recover completely, he emphasized. Hamilton responded that although the participants in the

patient focus groups he conducted were not randomly selected, he observed the reverse, with approximately 20–25 percent of TBI survivors experiencing full recovery with the remainder struggling with ongoing issues that were not treated in the weeks and months postinjury.

A participant described that his 28-year-old daughter experienced a head injury at the age of 5, and he was never told that she had a TBI. Although she would qualify as having a mild TBI, he reported that nothing about the injury’s effects on her life had been mild. She, like many others, received no follow-up care, and therefore she is not in any system that could be used to collect TBI data, he said. Given that so many people with TBI receive no or limited medical care, limited data is collected on the majority of TBI survivors, and accurate conclusions about the percentage of patients who recover fully cannot be well determined, he maintained. Manley reiterated that additional data are needed to fully understand the scope of the issue, and this gap warrants further investigation. Diaz-Arrastia acknowledged the need for better data and contended that this data gap does not eliminate the risk of overmedicalizing the condition, noting that factors identified as prognostic for poor recovery after mild TBI include preexisting psychological and personality factors. Michael McCrea, Medical College of Wisconsin, underscored the need for a neuro-bio-psycho-socio-ecological model of TBI (NASEM, 2022; Nelson et al., 2018) that considers not only the injury itself but also the person experiencing the injury and the patient’s response to injury.

Frederick Korley, professor and associate chair for research, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Michigan, commented that overmedicalizing mild TBI could lead to overburdening care clinics with patients who do not require this level of follow-up care, pointing again to the need for improved prognostic tools to prioritize those patients who are likely to experience longer-term symptoms. McCrea referred to the second recommendation in the National Academies TBI consensus study report, which states, “All people with TBI should have reliable and timely access to integrated, multidisciplinary, and specialized care” (NASEM, 2022). He emphasized that this statement does not equate to a recommendation that all individuals who experience mild TBI should be seen in a multispecialty clinic within a week of injury, but that those who experience ongoing symptoms should have a pathway to receive follow-up care. Current TBI specialty care models do not cover many parts of the United States, he said, thus a new model for improving follow-up care needs to be scalable in different care settings. Hammond added that funding, institutional involvement, and community engagement will also be needed to create pathways to care for individuals lacking insurance.

Patient Considerations in Resource Development

Noting the range of symptoms that can occur after TBI, Katherine Bowman, director of the Forum on Traumatic Brain Injury, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, asked how these symptoms can be considered in the process of creating the educational materials, resources, and apps described by the working groups. Hammond replied that materials will need to be designed with simplicity and understandability in mind so patients and their family members have access to needed information without feeling overwhelmed by these resources. McCrea added that the working group’s goal is not to treat 5 million individuals each year in specialty clinics; rather, the goal is to provide people with resources to inform decisions about whether further postacute care is warranted.

Hamilton commented that discharge is not an opportune time to convey detailed information to someone who has just experienced a TBI. Additionally, the patient focus group members with whom he spoke conveyed a dislike for generic materials. Personalized resources that include a patient’s name and are tailored to their type of injury are more likely to be used, he contended. Health care professionals can harness technology to help create such materials. Hamilton noted a recent study that indicated that written responses generated using ChatGPT, an artificial intelligence natural language processing tool, were as accurate and conveyed a more sympathetic tone than responses written by doctors (Ayers et al., 2023). Barde remarked that another important future focus of app development will be streamlining integration with other platforms to remove data silos that require patients to use multiple apps for their various health conditions and providers.

Engaging Relevant Medical Associations

Donald Berwick, president emeritus and senior fellow, Institute for Healthcare Improvement, asked about the extent to which Action Collaborative members exploring post-TBI care issues have connected with primary care professional associations to establish an outlet for the guidelines, patient education, and discharge instructions they aim to develop. Breiding replied that for the pediatric TBI population, CDC and others have developed connections with youth organizations, sports organizations, and pediatric medical societies. Expanding the footprint for adult TBI education will require additional efforts. McCrea noted that the TBI forum is a convening arena that can help establish such needed connections, given the presence of representatives from a variety of medical associations. That said, further engagement with primary care and family medicine communities would be beneficial. TBI treatment involves

a range of medical professionals and specialties, and wide representation in the forum can improve collective problem solving and strengthen dissemination capacity.