The Future Pediatric Subspecialty Physician Workforce: Meeting the Needs of Infants, Children, and Adolescents (2023)

Chapter: 5 Influences on the Career Path of a Pediatric Subspecialty Physician

5

Influences on the Career Path of a Pediatric Subspecialty Physician

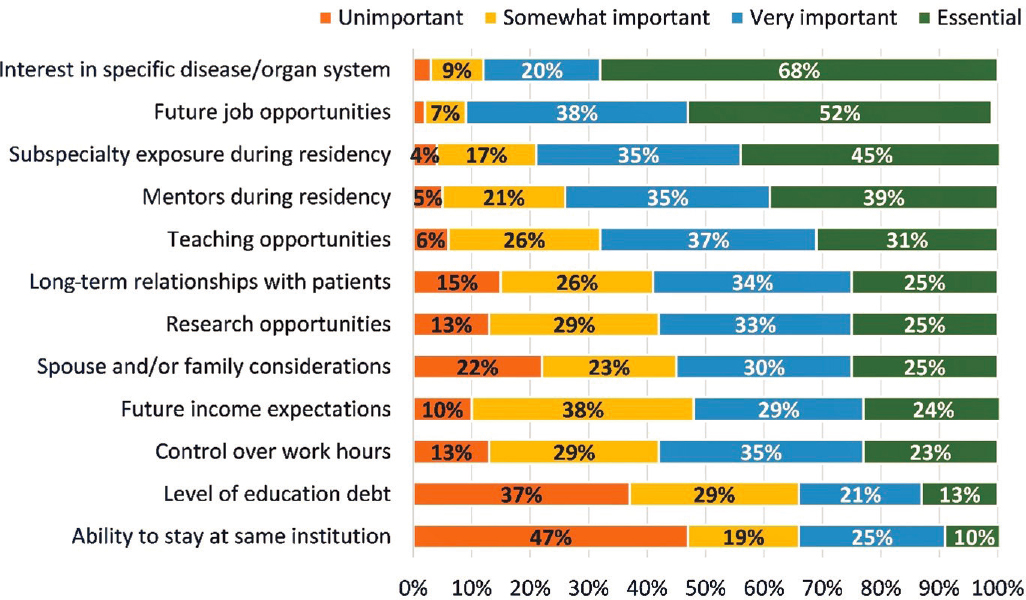

The majority of pediatric medical subspecialty physicians in the United States follow the typical career path of 4 years of medical school, followed by 3 years of pediatric residency and then 3 years of subspecialty fellowship training (ABP, 2022a,b).1 Major decisions along their career paths include: deciding to entering pediatrics in general, choosing to pursue subspecialty training, selecting a specific subspecialty, and choosing where and what type of practice. At each of those decision points, many factors may influence the outcome of that decision, including mentorship, personal interest, financial considerations, and lifestyle preferences. In choosing specialty training, medical students (in general) place the highest value on the content of the specialty and their personal interests, influential role models, and work–life balance (Youngclaus and Fresne, 2020). The decision to pursue a pediatric subspecialty is also affected by many of the same factors. Frintner and colleagues (2021a) used the 2019 American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Annual Survey of Graduating Residents to assess what factors influenced decisions to pursue pediatric subspecialty training. Among those who were planning to pursue such training, the highest rated factors were future job opportunities and interest in a specific disease/organ system, with most reporting these factors as essential or very important (90 percent and 88 percent, respectively). See Figure 5-1 for other factors identified as important in the decision to pursue fellowship training in a pediatric subspecialty.

___________________

1 One notable exception is that fellowship training for pediatric hospital medicine is 2 years (ABP, 2020). Non-standard pathways to certification may also apply in certain situations (ABP, 2022d).

SOURCE: Frintner et al., 2021a.

This chapter explores the influences—timing of exposure to pediatrics; education and training; coaching, mentoring, and role modeling; financing of graduate education; educational debt and earning potential; lifestyle preferences; and efforts in workforce planning, recruitment, and retention—that can encourage or discourage an individual from pursuing a career as a pediatric subspecialty physician. Many factors that can influence the choice to pursue a career in pediatrics can also influence the retention of clinicians in their chosen fields. Given limited evidence on some of these factors specific to pediatric subspecialists, drivers of career choices in medicine in general are also discussed, but the primary focus of this chapter is on the influences for a career as a pediatric subspecialty physician.

EXPOSURE TO PEDIATRICS

Early exposure to the medical specialty of pediatrics at various critical touch points, including high school and college, medical school, and early residency training, has been hypothesized to be critical in the decision to pursue a career in pediatrics and the pediatric subspecialties (Donnelly et al., 2007; Lindgren and Shah, 2023; Nelson et al., 2020; Vinci et al., 2021).

Before Medical School

An individual’s drive to pursue a career in pediatrics may be profoundly shaped by experiences that occur before entering medical school. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) compared students’ answers regarding a specialty preference on the 2022 Medical School Graduation Questionnaire to their previous answers on the Matriculating Student Questionnaire (administered during the summer before the first year of medical school) (AAMC, 2022a). Among all medical students, only 28 percent of students indicated the same preferred specialty upon graduation as they had intended upon matriculation. However, among students who indicated a preference for pediatrics upon graduation, nearly 45 percent had selected pediatrics at the beginning of medical school, suggesting that earlier life experiences may have had a significant impact on deciding to pursue a career in pediatrics. See Box 5-1 for clinician perspectives on the influence of their early exposure (before medical school) to pediatrics.

During Medical School and Residency

Experiences during medical school and residency also influence a student’s choice of specialty or subspecialty (Hauer et al., 2008; Pfarrwaller et al., 2015, 2017; Sozio et al., 2019; Tsai et al., 2022). The faculty of each medical school design the medical education curriculum, and there are no

specific requirements from the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) for exposure to topics such as pediatrics (LCME, 2023). Thus, medical students have variable exposure to pediatrics, and opportunities to enhance that exposure may be limited or occur late in the educational curriculum (Guiot et al., 2013; Laitman et al., 2019). Several institutions have offered preclinical electives in pediatrics in an effort to increase students’ confidence in caring for pediatric populations as well as to increase their interest in pediatrics as a career, but evidence of their impact is extremely limited (Keating et al., 2013; Laitman et al., 2019; Saba et al., 2015). See Box 5-2 for trainee and clinician perspectives on exposure to pediatrics during training.

Timing of Fellowship Decisions

Macy et al. (2018) found that 68 percent of individuals who entered pediatric subspecialty fellowship training first reported plans to do so at the start of their internship, and few changed plans to pursue such training. However, their selection of a specific subspecialty occurred across all 3 years of residency training, with the most common time being July of their second year of residency; nearly one-fifth of residents who entered fellowship training changed their choice of a specific subspecialty during

residency (Macy et al., 2018). In addition, international medical graduates were more likely than American medical graduates to decide on a specific pediatric subspecialty earlier in training.

Interest in the Specific Area of Specialization

One influence that may be intangible in influencing an individual’s choice of specialty or subspecialty is an academic or personal interest—something that potentially may be influenced by early exposure to that specialty or subspecialty. As noted earlier, simply being interested in the specific topic has been shown to be influential on medical students’ choice of specialty in general (Levaillant et al., 2020; Rao et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2019). In pediatrics, one survey of pediatrics residents found that “interest in a specific disease/patient population” was the highest ranked career factor in pursuing a pediatrics career (Orr et al., 2023), and a survey of graduating pediatric residents found that “interest in the specific disease/organ” was one of the most highly rated factors as influencing their decision

to pursue a specific fellowship (Haftel et al., 2020). The importance of interest in the specific area or the intellectual stimulation of the field has been documented for new pediatric subspecialists in general (Freed et al., 2016) as well as specifically in several pediatric subspecialties, including pediatric nephrology (Weinstein et al., 2010), pediatric endocrinology (Kumar et al., 2021), and pediatric pulmonology (Nelson et al., 2020). See Box 5-3 for trainee and clinician perspectives on how personal interest influenced their career choices.

EDUCATION AND TRAINING MODEL

While Chapter 1 presented a history of the development of subspecialty training and Chapter 4 provided the landscape of the current pediatric workforce, including an overview of the basic requirements of pediatric residency and fellowship training, the following sections emphasize some specific aspects of formal medical education and training that may directly influence an individual’s decision to pursue subspecialty training.

Requirements for Scholarly Activity in Fellowship

Currently, all pediatric subspecialty fellowships have a requirement for a core curriculum in scholarly activity (ABP, 2004, 2022b). The curricula for these activities are intended to develop an understanding of research-related skills such as biostatistics, research methodology, study design, and preparation of applications for research funding. Scholarly activity can be pursued in areas such as basic, clinical, and translational research; health services research; quality improvement; bioethics; education; and public policy. Scholarly projects are overseen by local scholarship oversight committees. Examples of appropriate scholarly activities include bench or clinical research, rigorous meta-analyses or systematic reviews, a critical analysis of a relevant public policy, or a curriculum development project (with an assessment component). Most fellows complete bench or clinical research (84 percent) and/or quality improvement activities or clinical care guideline development (50 percent) to meet these requirements (Freed et al., 2014a). At the end of the fellowship program, the fellow must finalize and submit a specific written product (e.g., peer-reviewed publication, successful grant application) (ABP, 2022c). However, the outcomes of pediatric subspecialty fellowship activities have not been fully assessed for either their contribution to the larger research enterprise or their impact on career trajectories.

The value of requiring all fellows to participate in scholarly activity as currently required, particularly for those individuals who do not plan to pursue a career that includes research, is an ongoing debate. Several justifications for this requirement have been proposed, including a need for subspecialists to have more a detailed understanding of the scientific process and the ability to critically assess new literature in order to safely bring new diagnostics and treatments to the children they care for, ones who are likely to have the most complex care needs; to provide exposure to career opportunities in research; and a maturation effect in which a trainee more fully develops and practices the total skill set of the subspecialist (e.g., teaching skills). Others have noted that this approach costs significant money and time (which may be a negative influence on the choice to pursue subspecialty training), and may be suboptimally executed because of lack of resources, mentorship, and in-depth education in research. See Box 5-4 for clinician perspectives on the requirement for scholarly activity. See Chapter 6 for more on the physician–scientist pipeline. The impact of research training requirements on the overall length of training is discussed later in this chapter.

Comparison with Internal Medicine Fellowships

The internal medicine model of fellowship training may provide insights on how to address issues of low enrollment into some pediatric subspecialties. Specifically, many internal medicine fellowships with similar clinical concentrations to pediatric fellowships (e.g., adolescent medicine, critical care, endocrinology, infectious disease, nephrology, pulmonary disease, rheumatology) only require 2 years of training (ABIM, 2023a). The American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) outlines specific clinical competence requirements for these fellowships, but does not have specific research requirements. ABIM does provide a research pathway for trainees who plan to pursue research careers; planning for this track is encouraged to occur during the first year of residency, and there are specific requirements for clinical training to accompany the research program (ABIM, 2023b). Internal medicine, however, also struggles with enrollment into some subspecialties. As shown in Table 5-1, the fill rates for ABIM-certified subspecialties with similar clinical concentrations for American Board of Pediatrics (ABP)-certified subspecialties tend to have higher fill rates overall. These data are for 2022 and show a point in time example that compares fellowship fill rates for pediatric versus adult subspecialties. (See Table 4-2 in Chapter 4 for data on average pediatric subspecialty fill rates over time.) Although there may be many reasons for these higher fill rates, including higher levels of compensation for adult subspecialists, training requirements

TABLE 5-1 Selected ABP-Certified and ABIM-Certified Subspecialties by Fellowship Fill Rate, 2022

| Subspecialty Area | Pediatrics | Internal Medicine | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NRMP- Reported Fill Rate | ABP-Calculated Final Fill Rate | NRMP-Reported Fill Rate | |

| Endocrinology | 59.1% | 75.5% | 98.3% |

| Infectious Diseases | 52.4% | 69.7% | 82.1% |

| Nephrology | 55.0% | 70.0% | 69.2% |

| Pulmonology | 73.5% | 85.5% | 92.0% |

| Rheumatology | 69.2% | 97.4% | 97.8% |

NOTES: Data reported from the NRMP do not necessarily reflect the final fill rate of training programs as some residents will be accepted outside of the NRMP process. Final fill rates for internal medicine subspecialties are unavailable, and so may also be higher than the NRMP-reported fill rates. See Chapter 4 for more information on ABP-calculated final fill rates for pediatric subspecialties.

SOURCES: ABP, 2023a; NRMP, 2022.

might be one factor that contributes to the decisions of trainees to pursue subspecialty training.

Overall Length of Education and Training

The length and structure of education and training to become a pediatric subspecialist may influence the choice of pursuing a subspecialty.

Initiatives to Accelerate Medical School Training

Several initiatives have explored opportunities to shorten the overall length of time required to become a physician. These initiatives provide examples of how education and training may be accelerated without compromising quality. The first modern-day accelerated baccalaureate medical programs opened in the early 1960s (Drees and Omurtag, 2012). The initial goal of these programs was to lessen the financial burden of medical education by allowing for the completion of a combined undergraduate and graduate medical education in 6 to 7 years rather than the typical 8 years; however, they soon became recognized as a viable way to quickly generate well-trained physicians (CAMPP, 2023; Drees and Omurtag, 2012; Kistemaker and Montez, 2022).

The Consortium of Accelerated Medical Pathway Programs was established in 2015 to develop 3-year M.D. programs to expedite medical

education and offer guidance to schools seeking to develop similar programs (CAMPP, 2023). Their primary goal is to make medical education more efficient and less expensive while maintaining student performance and competency. In 2012, there were only two accelerated M.D. programs in the country; by 2014 the number had grown to eight (Cangiarella, 2021). Today the Consortium includes more than 30 members who either offer or are planning to offer such programs. Graduates of accelerated programs perceive being prepared for residency and graduate with less debt as compared to 4-year M.D. students (Cangiarella et al., 2022; Leong et al., 2022).

Length of Residency and Fellowship Training

Overall length of training may influence the career path of a pediatric subspecialist; the appropriate length of training, particularly subspecialty fellowship training, is intertwined with the requirement for research during fellowship. In 2010, ABP hosted an Invitational Conference on Subspecialty Clinical Training and Certification (SCTC), with a task force subsequently charged with “examining the current model of pediatrics subspecialty fellowship training and certification with an emphasis on competency-based clinical training and recommending changes in the current requirements, if warranted” (Stevenson et al., 2014, pg.1). While the task force originally intended to focus on clinical training, its charge expanded to include the scholarly activity requirements of training, as those topics are intertwined. As part of the SCTC initiative, researchers surveyed current fellows (Freed et al., 2014a), program directors (Freed et al., 2014b), and recent graduates and mid-career professionals (Freed et al., 2014c) for each subspecialty (ABP, 2014; Freed et al., 2014d). These surveys revealed a wide range of opinions on the length of training and the clinical and research requirements by career stage.

While 87 percent of recent graduates and mid-career professionals agreed that the 12-month requirement for clinical training was appropriate, only 58 percent thought that the 12-month requirement for scholarly activity was appropriate (Freed et al., 2014c). Among those who did not agree with the 12-month requirement for scholarly activity, there were a range of opinions on whether that time should be increased, decreased, or eliminated. Although 76 percent of recent graduates and mid-career professionals thought that clinical training time should be equivalent for all fellows regardless of career path, only 46 percent thought the duration of scholarly activity should be equivalent; 31 percent of recent graduates and 26 percent of mid-career professionals thought there should be different tracks for clinical and research careers (Freed et al., 2014c). Furthermore, 43 percent of current fellows and 48 percent of recent graduates and midcareer professionals stated that their experience with scholarly activity did not affect their choice of a career path (Freed et al., 2014a,c). While 12 percent of current fellows and 22 percent of recent graduates and midcareer professionals said the scholarly activity experience influenced them

to work primarily in research, 13 percent of current fellows and 12 percent of recent graduates and mid-career professionals said the experience led them to change their career path to work primarily as a clinician (Freed et al., 2014a,c). The task force concluded that the joint ABP–Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requirements were sufficiently flexible for all subspecialties and trainees to achieve their goals (Stevenson et al., 2014). The task force also concluded that “although the current requirement for 3 years of subspecialty training will remain for now, as the ability to measure subspecialty training outcomes improves, the ABP may, in a staged and deliberate fashion, consider allowing fellowship training of shorter, longer, or variable lengths” (Stevenson et al., 2014, pg. S55). For example, the addition of pediatric hospital medicine as a certified subspecialty was approved as a predesigned 2-year fellowship (ABP, 2020). Importantly, the SCTC surveys were conducted more than 10 years ago, and it is unclear if the results would be the same today. See Box 5-5 for trainee and clinician perspectives on the length of fellowship training.

Alternative Pathways

While the standard model of research training in pediatric fellowship has routinely been implemented by programs as 12 to 24 months within the 3 years, ABP has alternate pathways available (see Box 5-6) (ABP, 2022d). Notably, these pathways have been specifically designed to provide options for future research-oriented trainees. Alternate pathways do not exist for trainees who want to focus their careers on clinical care. During one of the committee’s public webinars, Joanna Lewis, pediatric residency program director and director for mobile health services at Advocate Children’s Hospital in Park Ridge, IL, stated:

[Residents] see these physicians with very robust, fulfilling, satisfying clinical careers that do not involve research and they don’t find that fellowships seem to offer them the path to get to that spot. I think that becomes challenging for some of our residents when they’re making the decision about what fellowship to head into … I think a two-year fellowship with some experience with research—they all know that within subspecialty care and within all of us, our work is made better by there being research done and having evidence-based practice, and that doesn’t come out of thin air. I do think the three-year seems particularly daunting, especially to our residents that have a lot of debt and know that in some of these subspecialties they will put three more years into not making more money than if they went into general pediatrics right away. Also, many of our residents are helping to support their family members, so it is even more of a strain to continue to take on additional training.2

___________________

2 The webinar recording can be accessed at https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/09-06-2022/the-pediatric-subspecialty-workforce-and-its-impact-on-child-health-and-well-being-webinar-2.

Training Locations

The location of residency and fellowship programs may impact both an individual’s choice of a residency or fellowship, choice of subspecialty, and subsequent choice of practice location upon graduation. In general, physicians have a high likelihood of practicing in the state in which they completed graduate medical education (GME) (Fagan et al., 2015; Seifer et al., 1995) and training in rural and underserved settings increases future practice in these settings (Goodfellow et al., 2016; Morris et al., 2008; Phillips et al., 2013; Russell et al., 2022).

The 2022 AAMC Report on Residents reveals that 60 percent of the individuals who completed pediatric residency training from 2012 through 2021 and did not pursue subspecialty training are practicing in the state where they did their residency training (AAMC, 2022b). Similarly, as shown in Table 5-2, on average, more than half of pediatric subspecialists ultimately practice in the states where they complete their residency training. This may be due to a tendency for subspecialists to pursue fellowship training at the same institution as their residency, or lifestyle factors that influence an individual’s choice of training location. Women are more likely than men to remain in the state where they completed their residency training.

COACHING, MENTORSHIP, AND ROLE MODELING

Early and consistent presence of coaches, mentors, and role models can be important influences on an individual’s choice to both specialize in pediatrics as well as pursue training in a pediatric subspecialty. A definition of mentorship put forth in the National Academies report The Science of Effective Mentorship in STEMM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics, and Medicine) is “a professional, working alliance in which individuals work together over time to support the personal and professional growth, development, and success of the relational partners through the provision of career and psychosocial support” (NASEM, 2019a, pg 2). That report highlighted the multiple forms that mentorship can take, ranging from the typical/standard dyadic relationship, peer and near-peer interactions, and experience, to national workshops, seminars, and programs. The emphasis on psychosocial as well as career support highlights the important roles of emotional support and role modeling, which can be particularly impactful for mentees from backgrounds underrepresented in medicine (URiM). These supports can potentially mitigate unsupportive or hostile environments while reforms or strategies are implemented at institutional or societal levels to combat/dismantle structural racism and other barriers to the inclusion, retention, and advancement of pediatric subspecialists from

TABLE 5-2 Pediatric Subspecialist Retention in State of Residency Training by Gender, 2012–2021

| Subspecialty | Percentage Remaining in State (Overall) | Percentage Remaining in State (Men) | Percentage Remaining in State (Women) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescent Medicine | 60.2 | 56.1 | 61.4 |

| Child Abuse Pediatrics | 54.4 | 33.3 | 57.7 |

| Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics | 60.7 | 43.5 | 64.2 |

| Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine | 59.5 | 52.6 | 62.6 |

| Pediatric Cardiology | 45.0 | 42.0 | 48.5 |

| Pediatric Critical Care Medicine | 56.0 | 53.2 | 58.0 |

| Pediatric Emergency Medicine | 61.5 | 56.9 | 64.0 |

| Pediatric Endocrinology | 60.5 | 57.2 | 61.4 |

| Pediatric Gastroenterology | 57.9 | 51.9 | 61.7 |

| Pediatric Hematology/Oncology | 60.5 | 59.5 | 61.2 |

| Pediatric Hospital Medicinea | 78.9 | 100.0 | 66.7 |

| Pediatric Infectious Diseases | 58.7 | 62.4 | 56.6 |

| Pediatric Nephrology | 57.1 | 61.1 | 55.5 |

| Pediatric Pulmonology | 63.8 | 60.3 | 65.7 |

| Pediatric Rheumatology | 59.3 | 48.3 | 63.4 |

NOTE: aThe percentage for pediatric hospital medicine reflects only a very small number of residents given that the first examination for certification was administered in 2020.

SOURCES: AAMC, 2022b,c.

URiM backgrounds. Early exposure to mentors and role models may be particularly important for students from URiM backgrounds. For example, one small study of 20 medical students from URiM backgrounds showed that mentorship and having role models from URiM backgrounds influenced their decisions to pursue academic pediatrics (Dixon et al., 2021).

In academic medicine, mentored experiences have been associated with a number of positive benefits, including job satisfaction and higher academic self-efficacy, although there are reports of less-than-optimal mentoring during fellowship training (Diekroger et al., 2017; Feldman et al., 2010). Mentors can serve as role models and advisors for future subspecialists, and their presence can enhance mentees’ learning experiences (Nelson et al., 2020). One study of graduating pediatrics residents showed that most (87 percent) had a mentor who provided career advice; of those, nearly half (45 percent) had mentors who were subspecialists (Umoren and Frintner,

2014). The study further found that residents with subspecialist mentors were more likely to seek subspecialty training. A survey of 12 pediatric hospitalist fellows showed that most reported subspecialty-specific mentorship as being important during residency in supplementing the development of clinical skills (Patel et al., 2021). Within the subspecialty of pediatric infectious disease, faculty and fellows have encouraged students to join the subspecialty by inviting them to shadow their clinical practice and connecting them with minority prehealth professional organizations (Rogo et al., 2022).

FINANCING OF GRADUATE MEDICAL EDUCATION

GME, which includes initial residency and subsequent fellowship training, is a critical step in the physician pipeline. It is through GME that physicians specialize and subspecialize. In addition, to be independently licensed in any state, physicians must complete at least one year of GME in a U.S. program (FSMB, 2018).3 Therefore, the availability of GME positions determines both the overall number and the specialty distribution of the physician workforce.

GME also represents the largest public investment in the health workforce. Funding for pediatric residency programs can come from Medicare, Medicaid, the Children’s Hospital Graduate Medical Education (CHGME) program, and the Teaching Health Center Graduate Medical Education (THCGME)4 program. In FY2020, Medicare GME provided the largest share of GME funding estimated at $16.2 billion (CRS, 2022); in FY2022, Medicaid GME provided $7.4 billion of federal and state funding (AAMC, 2023). In 2018, THCGME obligated $119 million to increase the number of primary care residents and dentists training in community-based, ambulatory patient care centers (GAO, 2021a). (Financing levels of CHGME are discussed later in this section.)

According to AAMC, in academic year 2021–2022, there were 9,219 pediatric residents, 1,519 residents in the combined program of internal medicine/pediatrics, and 4,417 pediatric medical subspecialty fellows5

___________________

3 In most states, additional years of GME are required for international medical graduates. Some states accept GME completed in Canada to meet licensing requirements (FSMB, 2018).

4 The THCGME program was established in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010. The program provides GME payments to new or expanded primary care residency programs located in community-based settings. In academic year 2022–2023, 4 out of 102 awardees were in pediatrics (HRSA, 2022c).

5 The count of pediatric medical subspecialty fellows includes fellows from the 15 ABP-certified subspecialties plus fellows in clinical informatics (30 total), pediatric sports medicine (25 total), and pediatric transplant hepatology (16 total) (AAMC, 2022d).

(AAMC, 2022d). The CHGME program supported the training of 6,124 pediatrics residents6 and 3,201 pediatric medical subspecialty fellows (including 206 child and adolescent psychiatry fellows) in 2021–2022 (HRSA, 2023a). While some pediatricians are trained in Medicare GME hospitals, the majority of pediatric medical subspecialty fellows were trained in freestanding children’s hospitals supported by the CHGME program.

Role of Medicare in Graduate Medical Education

Medicare GME payments make up the largest portion of public funding for residency training programs. Medicare GME is mandatory funding with payments, based on the statutory formulas, guaranteed annually. In 2018, Medicare provided GME payments to 1,319 hospitals, and 70 percent of training hospitals were training at least one more resident than was covered by the Medicare-funded cap (GAO, 2021b). A 2008 study found that much of the growth in residency positions after the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 established hospital resident caps was in non-primary care specialty and subspecialty fields (Salsberg et al., 2008). Medicare GME has been criticized for concerns of overpayment, geographic maldistribution, and lack of transparency and accountability. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) and the Institute of Medicine (IOM)7 have both recommended major GME reforms. In their June 2010 Report to Congress, MedPAC identified two major areas of concern for GME—workforce mix and education and training in the skills needed to improve the value of health care delivery systems—and included among their recommendations:

- Congress should authorize the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (Secretary) to change Medicare’s GME funding, establishing new standards for distributing funds, goals for learning, and performance-based funding;

- The Secretary should conduct workforce analysis to determine the number of residency positions, in total and by specialty, needed in the United States, and annually publish a report on GME payments and associated costs to hospitals; and

___________________

6 The pediatric residents included general pediatrics residents as well as residents from eight types of combined pediatrics programs (HRSA, 2023a).

7 As of March 2016, the Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (National Academies) continues the consensus studies and convening activities previously carried out by the Institute of Medicine (IOM). The IOM name is used to refer to reports issued prior to July 2015.

- The Secretary should study strategies for increasing workforce diversity (MedPAC, 2010).

In 2014, the IOM found GME financing to be outdated and in need of significant reform (IOM, 2014). The IOM recommended maintaining the current level of Medicare GME funding, but replacing the direct and indirect payments with a single, streamlined, performance-based payment within existing funds, establishing a GME Transformation Fund to “develop and evaluate innovative GME programs, to determine and validate appropriate GME performance measures, to pilot alternative GME payment methods, and to award new Medicare-funded GME training positions in priority disciplines and geographic areas” (IOM, 2014, p.133). The IOM also recommended the creation of a GME Policy Council at the level of the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and a GME Center in the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to administer reforms, manage demonstrations of new payment models, and ensure strategic investments. To date, these recommendations have not been implemented.

Role of the Children’s Hospital Graduate Medical Education Program

The CHGME program was established in the Healthcare Research and Quality Act of 1999 to provide GME payments to freestanding children’s hospitals. Prior to the CHGME program, the Medicare program provided payments based on the Medicare share of total inpatient days for direct GME payments and as an add-on to the Medicare inpatient prospective payment system for indirect GME payments. Therefore, freestanding children’s hospitals qualified for minimal Medicare GME payments because so few children are on Medicare. The CHGME program filled a gap in federal GME support.

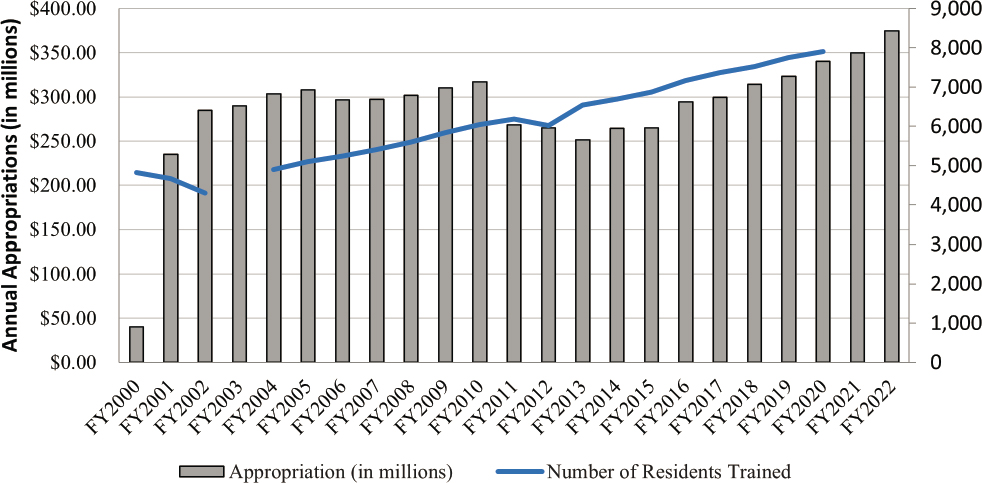

Since its inception in 2000, the CHGME program has been authorized for annual appropriations of $280–$330 million, and briefly from 2002 to 2005, to “such sums as may be necessary” (CRS, 2021). Program funding has had significant year-to-year variation (see Figure 5-2), but since FY2014, there has been a steady increase in appropriations. The program was funded at $375 million for FY2022 and 385 million8 for FY2023, which is historically the highest level of funding for the program and above the currently authorized level of $325 million (CRS, 2023). The number of CHGME hospitals has ranged from 54 to 61 (CRS, 2023). In FY2022, there were 59 CHGME hospitals across 29 states, the District of Columbia, and

___________________

8 The CHGME funding level for FY2023 was corrected after release of the report to the sponsors.

NOTE: *Data for FY2003 residents are missing.

SOURCES: CRS, 2021; HRSA, 2022a.

Puerto Rico. Annual award amounts ranged from $30,273 to $26.2 million (median award $4.1 million).9

Although CHGME payments are similar to Medicare GME in structure, there are key differences. Similar to Medicare, direct and indirect payments are calculated based on formulas, and a cap on the number of residents is applied to each hospital. The resident cap limits the number of resident positions eligible for payment, although hospitals can train above the cap if they are able to fund the extra positions. During one of the committee’s public webinars, Mary Leonard, Arline and Pete Harman Professor and Chair of the Department of Pediatrics at Stanford University, director of the Stanford Maternal and Child Health Research Institute, and physician-in-chief of Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital, described difficulties related to the small clinical margin in pediatric departments:

Our children’s hospital has a very small margin compared to the adult hospital….It has huge implications for funding the education programs…my single biggest line item, just the discretionary funding and how I use my clinical profit, is fellowships…it’s increasingly becoming a challenge for my department. We’re very, very fortunate…the Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital spends $40 million on GME. And so, they fund all my first year fellows and for some they fund the second and third year. It’s the obvious ones. It’s [neonatal-perinatal] and critical care. But I have 54 second and third year fellows who I am responsible for covering their salary…We were so fortunate about 20 years ago to get an endowment to support some of our second and third year fellows, but that is completely flat, whereas my number of fellows has increased very, very dramatically. So, this year it was a tipping point in terms of the challenges that I’m having because I’m thrilled when we get ACGME approval and hospital support to expand my nephrology fellowship or my ID fellowship, and then I go…I have four more mouths to feed.10

In contrast to Medicare, CHGME is a discretionary program and payments are ultimately limited by the amount of annual appropriations. Hospitals receive a portion of their payments based on the annual appropriation level and new CHGME hospitals can mean decreased payments across existing hospitals. In 2018, the GAO estimated that the average unadjusted Medicare GME payment per full-time resident in 2015 was $117,674 while CHGME paid $51,778 per resident and Medicaid GME paid $36,540 per resident (GAO, 2018). Under the CHGME program,

___________________

9 These data were generated using the “Find Grants” dashboard at https://data.hrsa.gov/tools/find-grants (accessed May 7, 2023).

10 The webinar recording can be accessed at https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/07-19-2022/the-pediatric-subspecialty-workforce-and-its-impact-on-child-health-and-well-being-webinar-1.

hospitals must report on the number of residents trained in each specialty, the types of training provided related to the health care needs of different populations (e.g., children who are underserved due to family income or rural/urban location), changes in curriculum and training experiences, and the number of residents who graduate and practice within the same state. In her presentation to this committee, Dr. Leonard discussed the impact of CHGME funding on fellowships:

[CHGME] supports the training of most of the country’s subspecialists, but the funding per training is less than half of that for Medicare GME. Medicare GME is growing reliably annually, but the CHGME is not. So, that’s been a big issue. And there’s a really nice body of literature around fellowship funding insecurity. Not surprisingly, the disciplines that earn money for the hospital, the NICU [Neonatal Intensive Care Unit], the PICU [Pediatric Intensive Care Unit], emergency medicine, some of the big fellowships are really getting the preponderance of the funding from the hospitals…there is no financial support through CHGME for the research training that’s necessary to facilitate the career development of physician scientists and to meet the ABP [American Board of Pediatrics] requirement for scholarly activity.11

The CHGME program is unique in that the 2013 reauthorization of the program established a Quality Bonus System (QBS) to link payment to program quality measures. The FY2023 CHGME funding opportunity states that the goal of QBS is “to recognize CHGME Payment Program awardees that provide high-quality training and to incentivize the participating children’s hospitals to meet the pediatric workforce needs of the nation” (HRSA, 2022b). In FY2023, hospitals must meet a pay-for-reporting requirement to qualify for the quality bonus payment (i.e., hospitals must complete individual-level documentation for all residents supported by the CHGME program). In FY2019, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) awarded a QBS evaluation contract to develop quality measures for GME programs. However, quality measures have not been released beyond the pay-for-reporting requirement. The available funds for QBS are limited in statute to any amount remaining after payments are made to a set of hospitals deemed newly qualified for the CHGME program in the 2013 reauthorization. The total amount for the newly qualified hospitals and the Quality Bonus Systems cannot exceed $7 million. In FY2021, the CHGME program provided $1.8 million in QBS payments to 32 of the 59 awardees (HRSA, 2022a). While the QBS is an important policy mechanism to link

___________________

11 The webinar recording can be accessed at https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/07-19-2022/the-pediatric-subspecialty-workforce-and-its-impact-on-child-health-and-well-being-webinar-1.

GME funds to priority pediatric workforce needs, the available amount spread across up to 59 hospitals is unlikely to be sufficient to incentivize meaningful change.

Role of Medicaid in Graduate Medical Education

State Medicaid programs can also support GME. As noted earlier, federal and state payments for Medicaid GME (including 44 states and DC) reached an estimated $7.4 billion in 2022 (AAMC, 2023). While many states mirror the Medicare direct and indirect payment method, some states have used their Medicaid programs to innovate, including consolidating to a single GME payment, providing payments directly to medical schools or ambulatory care centers, and other health profession trainees, most often graduate nurses. Additional state innovations include creating GME innovation pools, funding rural rotations and/or providing funding to start new residency programs or expand existing programs, and establishing oversight bodies to bring interested parties together and decide how funds could be targeted to meet specialty, geographic, or other workforce needs (Fraher et al., 2017).

EDUCATIONAL DEBT AND EARNING POTENTIAL

Financial disincentives such as educational debt and earning potential may influence an individual’s choice to pursue training in pediatrics in general, as well as the choice to pursue additional training in a specific subspecialty. As discussed previously, debt burden and income do not typically rank among the highest factors in surveys of influences on career decisions; however, such disincentives may weigh more heavily on the decisions for certain groups.

Educational Debt

Data from AAMC show the median educational debt for medical students in general (including both medical school debt and educational debt incurred before medical school) in 2019 was $200,000 (Youngclaus and Fresne, 2020). Debt ranked lower in importance as an influence on specialty choice for medical students than other factors such as the content of the specialty area, role models, and work–life balance. However, educational debt may more strongly influence the choice of a career in primary care for medical students from economically disadvantaged backgrounds (Phillips et al., 2014).

In pediatrics, roughly 75 percent of graduating residents report having educational debt; that percentage has remained consistent over the past

decade, while the average amount of debt has steadily increased (Cull et al., 2017). A large amount of educational debt combined with typically lower earning potential for pediatrics and the pediatric subspecialties (as compared with their adult internal medicine counterparts) may hinder recruitment (Catenaccio et al., 2021a; Catenaccio et al., 2021b; Rochlin and Simon, 2011). Using 2013 survey data from the AAP Pediatrician Life and Career Experience Study, Cull et al. (2017) found that pediatric subspecialists were more likely than other pediatricians to be concerned about their debt, even up to 10 years after completing training.

Furthermore, there are disparities in the level of debt burden. For example, medical students from URiM backgrounds have more educational debt, which may further complicate recruitment of URiM candidates to subspecialty careers (Dugger et al., 2013; Orr et al., 2023; Toretsky et al., 2018, 2019; Youngclaus and Fresne, 2020). In 2019, medical school graduates (in general) who identify as Black, not Hispanic had a median education debt of $230,000, in comparison with a median debt of $200,000 for all students, $200,000 for White, not Hispanic students, and $190,000 for Hispanic students (Youngclaus and Fresne, 2020). Orr et al. (2023) found that self-reported educational debt was associated with a trainee’s self-reported race/ethnicity, with one-third of individuals who identify as Black/African American having more than $300,000 in educational debt. See Box 5-7 for clinician perspectives on their debt burden.

Earning Potential

In the broader literature on earnings, female-dominated professions tend to have lower earnings than male-dominated ones, including medicine (IWPR, 2021; Levanon et al., 2009; Pelley, 2020). For example, a cross-sectional study of more than 54,000 academic physicians found that women had lower starting salaries than men in 42 of 45 subspecialties and lower earning potential in 43 of the 45 subspecialties (Catenaccio et al., 2022). Regarding pediatrics specifically, Frintner et al. (2019) concluded that “early- to mid-career female pediatricians earned less than male pediatricians” and added that “this difference persisted after adjustment for important labor force, physician-specific job, and work–family characteristics.” They initially found that women earn 76 percent of what men earn, or approximately $51,000 less. Adjusting for a variety of workforce, job, and work–family characteristics, they found that women earned approximately 94 percent of men’s earnings, or roughly $8,000 less annually (Frintner et al., 2019). These findings are particularly important for pediatrics and the pediatric subspecialties given the increasing percentage of women pursuing careers in pediatrics and the pediatric subspecialties (see Chapter 4).

Pediatricians are among the lowest paid specialists, even among primary care specialties (Doximity and Curative, 2023; Kane, 2022). Frintner et al. (2019) found that pediatricians in the larger subspecialties (e.g., neonatology, cardiology, critical care, emergency medicine, gastroenterology, and hematology/oncology) reported overall mean earnings of $231,930, while pediatricians in the smaller subspecialties (all other pediatric medical subspecialties) reported overall mean earnings of $168,245, and general pediatricians reported overall mean earnings of $180,250. A more recent survey (in 2022) on payment for physician specialties revealed that pediatrics overall and pediatric subspecialties tended to have the lowest compensation, and surgical specialties received the highest compensation; in fact, ABP-certified pediatric subspecialties represented 8 of the 20 lowest paying specialties, and the 5 specialties with the lowest compensation were all ABP-certified subspecialties (i.e., pediatric endocrinology, pediatric infectious disease, pediatric rheumatology, pediatric hematology and oncology,

and pediatric nephrology) (Doximity and Curative, 2023). Among these five subspecialties, total average compensation ranged from $218,266 for pediatric endocrinology to $238,208 for pediatric nephrology.

Lakshminrusimha and colleagues (2023) found that the benchmark compensation for most academic pediatric medical subspecialties was lower than the benchmark compensation for their adult counterparts. For example, the compensation for pediatric gastroenterology was 70 percent of the compensation for adult gastroenterology; pediatric infectious disease, pediatric rheumatology, and pediatric endocrinology academics were compensated at 90 percent of the compensation of their adult counterparts. On the other hand, they showed that pediatric surgeons earned 134 percent of the compensation for adult surgeons (Lakshminrusimha et al., 2023).

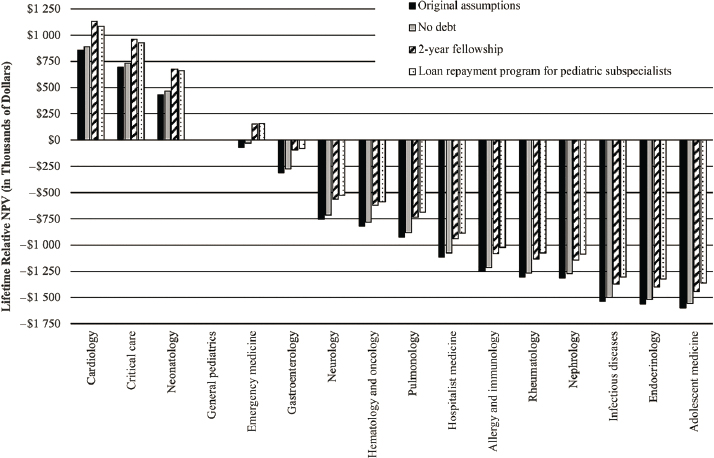

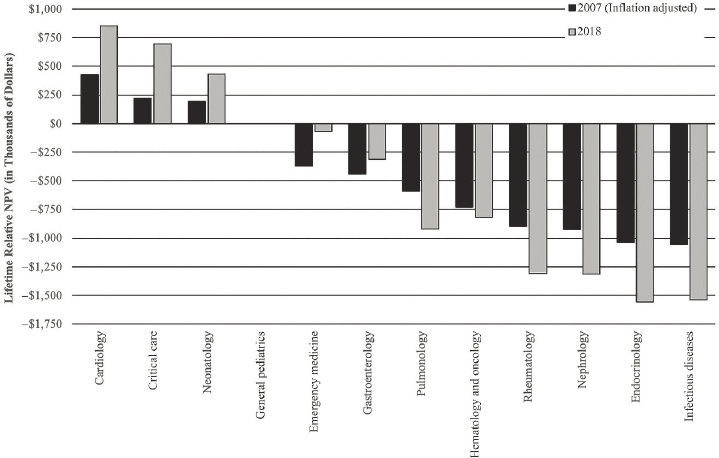

A 2021 study showed that the lifetime financial return on investment for pediatric subspecialty training, compared with general pediatrics, was negative for 12 of the 15 subspecialties examined (Catenaccio et al., 2021b). Only subspecialty training in cardiology, critical care, and neonatology resulted in a positive lifetime financial return (Figure 5-3). Furthermore, the relative difference in financial returns among subspecialties is increasing. Over a 10-year period, the difference between subspecialties with positive financial returns (as compared with general pediatrics) and subspecialties

SOURCE: Adapted from Catenaccio et al., 2021b. Reproduced with permission from Pediatrics, Copyright ©2021 by the AAP.

SOURCES: Adapted from Catenaccio et al., 2021b. Reproduced with permission from Pediatrics, Copyright ©2021 by the AAP.

with negative financial returns is even greater. (See Figure 5-4.) See Chapter 8 for more on physician payment.

Scholarship and Loan Repayment Programs

Scholarship and loan repayment programs aim to reduce financial barriers to entry for health professions careers and/or provide a financial incentive, leveraging student debt, for a desired health workforce outcome such as specialty choice or practice in an underserved setting. In 2019, among all medical students with the highest levels of debt, nearly half reported plans to seek loan forgiveness through a public service program (Youngclaus and Fresne, 2020).

National Health Service Corps

HRSA’s National Health Service Corps (NHSC) is one of the best known programs providing scholarships or loan repayment in exchange for a minimum of 2 years of clinical services provided in an area with a shortage of health professionals. NHSC supports primary care physicians,

nurse practitioners, physician assistants, dentists, pharmacists, and mental health professionals (HRSA, 2021). Pediatric behavioral and mental health subspecialists qualify for NHSC, but other types of pediatric subspecialists are not eligible. In 2022, NHSC supported 2,587 primary care physicians as well as 4,031 nurse practitioners and 1,558 physician assistants providing primary care (HRSA, 2023b). Nearly 70 percent of NHSC primary care practitioners are retained in a health professional shortage area over the 10 years after service (The Lewin Group, Inc., 2016).

Pediatric Specialty Loan Repayment Program

The Pediatric Specialty Loan Repayment Program, administered by HRSA, was established in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, offering up to a $35,000 loan repayment a year for each year of full-time services providing pediatric medical subspecialty, pediatric surgical specialty, or child and adolescent mental and behavioral health care, including substance abuse prevention and treatment services for up to 3 years. The qualifying time of service can be during residency or fellowship training. The program was originally authorized at $30 million annually for pediatric medical and surgical specialists and $20 million for child and adolescent behavioral health specialists. However, the program was funded for the first time in FY2022 at only $5 million as part of the Consolidated Appropriations Act12 and again in FY2023 at $10 million (HRSA, 2023c). In June 2023, HRSA opened the first application cycle for this program, expecting to make up to 150 awards with the initial $15 million appropriated by Congress (HRSA, 2023d). Similar to the NHSC, the program has a full-time service commitment; this requires that the specialist provide clinical care for at least 36 hours per week and for at least 45 weeks per year. The clinical care requirement applies for those in practice and in residency or fellowship training. This requirement may preclude pediatric subspecialty researchers from applying for this program.

National Institutes of Health (NIH) Loan Repayment Programs

Loan repayment for pediatric research is another potentially important program for pediatric subspecialty careers. “Since 1988, the NIH Loan Repayment Programs have been successful in recruiting and retaining early-stage investigators into promising biomedical and behavioral research careers” (Lauer, 2019). One of the programs focuses specifically on pediatric research. In this program, NIH can repay up to $50,000 in educational

___________________

12 The Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2022, Public Law 117-103, 117th Cong., 2d sess. (March 15, 2022).

loans per year in exchange for a commitment to research for at least 20 hours per week for at least 2 years (with possibility for renewal) (NIH, 2022a). In FY 2022, the mean award for new applications was $88,669 while the mean for renewals was $47,720; the mean age of new awardees was 36 years (NIH, 2023). (See Chapter 6 for more on NIH Loan Repayment Programs.)

J-1 Visa Waiver Program

The J-1 Visa Waiver program is one policy mechanism used to recruit and retain non-U.S. citizen international medical graduates. International medical graduates are an important part of the physician workforce. As noted in Chapter 4, nearly 21 percent of general pediatrics residents (not in combined programs or alternate pathways) and 27 percent of first-year ABP-certified subspecialty fellows are international medical graduates (ABP, 2023b,c). The J-1 is an exchange visitor visa that allows individuals to receive graduate medical education or other training. A J-1 visa holder would normally be required to physically reside in their country of nationality (or last residence) for at least 2 years upon completion of their exchange program. The J-1 Visa Waiver program waives the 2-year foreign residence requirement. Also known as the Conrad 30 Waiver Program, named after Sen. Kent Conrad from North Dakota who originally sponsored the legislation in 1994, the program provides each state with up to 30 J-1 visa waivers per year. A 2022 study of Maryland’s J-1 Visa Waiver program suggests the program has been effective in attracting physicians to work in primary care and with high-need, low-income patients (Quigley, 2022). However, any policies to increase international recruitment of health professionals should consider global health workforce impacts. While global mobility and opportunity are worthy societal goals, U.S policies to address national physician workforce shortages can negatively impact global health systems, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (Mullan, 2005; Tankwanchi et al., 2013).

INFLUENCES ON LIFESTYLE

In general, lifestyle, work–life balance, and spousal considerations are among the factors that have the most influence on medical students and residents’ choice of specialty and career path (Levaillant et al., 2020; Newton et al., 2005; Rao et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2019). A factor that has become increasingly important for clinicians in their choice of specialty or subspecialty is the perceived control over work-related lifestyle (Dorsey et al., 2003; Enoch et al., 2013; Haftel et al., 2020). General pediatrics residents as well as pediatric subspecialists have also specifically expressed the

importance of lifestyle on their career paths (Amoli et al., 2016; Freed et al., 2009; Freed et al., 2016). One study of pediatric hematologist/oncologists showed that they preferred a balance of direct patient care, inpatient service and office-based outpatient care, and non-clinical time, and that they specifically sought jobs in settings that supported that balance, which were more likely to be larger medical centers with greater concentrations of subspecialists who could share the on-call burden (Frugé et al., 2010).

Gender may also play a role in prioritizing work–life balance and flexibility (e.g., through part-time work) (Enoch et al., 2013; Freed et al., 2017; Wiley et al., 2002; Women Chairs of the Association of Medical School Pediatric Department Chairs, 2007). Women prioritize lifestyle factors and interest in flexible work hours as compared to men (Freed et al., 2009; Harris et al., 2005). Female early-career pediatricians typically spend more time on household responsibilities and the care of their own children than male pediatricians (Starmer et al., 2016, 2019). In addition, one survey of new pediatric subspecialists showed that women were more likely than men to be employed part time and were more likely to foresee part-time work within the coming 5 years (Freed et al., 2016). However, the study also showed that about one-third of the respondents who reported working part time were still working more than 40 hours per week. Powell et al. (2021) found that graduating female pediatric residents were more likely to prioritize factors such as number of overnight calls per month, option to work part time, length of parental leave, and availability of onsite childcare in positions after residency as compared with male residents. See Box 5-8 for trainee and clinician perspectives on the influence of lifestyle factors. See later in this chapter for discussions of job satisfaction and burnout.

WORKFORCE PLANNING AND RECRUITMENT EFFORTS

Federal and state governments along with the private sector invest in a number of programs designed to support and develop the health care workforce, either overall or specifically for pediatric subspecialties. Aside from its role in loan repayment, NHSC, discussed earlier, is one program that seeks to get more clinicians into geographic areas that have shortages of health professionals.

Pediatrics 2025: AMSPDC Workforce Initiative

The Association of Medical School Pediatric Department Chairs (AMSPDC) workforce initiative was created in 2020 to meet the health and wellness needs of children by increasing the number and diversity of students entering pediatrics and improving the supply of pediatric subspecialists (AMSPDC, 2023). The initiative includes four areas of focus, or

domains. The first domain, “Changing the Educational Paradigm,” focuses primarily on influencing and attracting students into pediatrics and high-priority subspecialties by advocating for educational change to regulatory agencies, exploring ways to redesign educational curricula (including more flexible training pathways), increasing early exposure to subspecialties, and enhancing positive role modeling. The second domain, “Workforce Data/Needs and Access,” focuses primarily on understanding the needs and trends within the pediatric workforce, including gathering data on the diversity of pediatric clinicians, models of care, and referral patterns. The third domain, “Economic Strategy,” focuses on ways to minimize educational debt and strategies to achieve parity with other providers. The final domain, “Recruitment/Outreach and Early Integration,” primarily examines other avenues to attract medical students to pediatrics, including early

exposure at high school and college levels, marketing strategies, increased shadowing opportunities for preclinical medical students, and incorporating pediatrics into preclinical curricula.

Underrepresented Populations

Evidence increasingly supports the importance of a diverse health workforce. In general, physicians from URiM backgrounds or who grew up in rural or urban underserved areas are more likely to serve underserved populations (Goodfellow et al., 2016; Marrast et al., 2014). Patient–provider demographic concordance may be associated with improved patient outcomes (Alsan et al., 2019; Shen et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2019) and diversity in medical schools produces educational benefits such as cultural

awareness and decreased bias (Saha et al., 2008; van Ryn et al., 2015). A recent scoping review of 27 articles across various medical and surgical specialties found that combinations of interventions, including holistic review, lower emphasis on examination scores, and explicit messaging about the importance of diversity, led to increases in URiM applications, interviews, and matriculation into residency and fellowship (Mabeza et al., 2021). However, recruitment to increase representation in the health care workforce continues to be a challenge for the medical field in general. Additionally, recent state-based initiatives to prohibit programs and training aimed at diversity, equity, and inclusion at public colleges and universities may serve as significant barriers to increasing representation or may even influence a prospective fellow’s choice of training location (Acevedo, 2023; Curran, 2023; Reddy and Olivares, 2023). Intentional initiatives will be needed to effectively increase representation of URiM physicians. During one of the committee’s public webinars, Denise Cora-Bramble, inaugural chief diversity officer at Children’s National Medical Center, stated:

At the national level, what we see is if we look at those numbers of the percentage of those that are [URiM], for residents, there isn’t much change if you look at the last 10 years or so. And for fellows, it’s actually decreased. I would say that from my perspective, unless we in the institutional level have some very intentional and direct strategies to address this, the numbers are just not going to change by themselves.13

General Efforts to Increase Representation in Medicine

HRSA’s Health Careers Opportunity Program (HCOP), Centers of Excellence (COE), and Area Health Education Centers (AHEC) focus on enhancing opportunities for medical students from racial/ethnic minority and disadvantaged backgrounds. The goal of HCOP is to identify, recruit, and support students from disadvantaged backgrounds for education and training for a career in health care professions. COE supports health professions schools that have higher enrollments of students from underrepresented racial/ethnic backgrounds. AHEC supports education and training networks between communities and academic organizations with the goal of increasing diversity of health professionals, improving their distribution, and enhancing quality of care.

NIH maintains the Science Education Partnership Award programs, which support educational projects in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics for prekindergarten through grade 12, and summer internship

___________________

13 The webinar recording can be accessed at https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/07-19-2022/the-pediatric-subspecialty-workforce-and-its-impact-on-child-health-and-well-being-webinar-1.

programs for high school students, including the High School Scientific Training and Enrichment Program (HiSTEP) and HiSTEP 2.0, which focus on students from high schools in the Washington, DC metropolitan area with a high percentage of financially disadvantaged students (NIH, 2022b). The Indian Health Service supports the Health Professions Recruitment Program for Indians which, in part, helps American Indians and Alaska Natives to pursue careers in health professions (TAGGS, 2022). Older studies examining the impact of these programs demonstrate that interventions at the high school-and college-level programs had positive effects, including matriculation to medical school and employment in health professions (HHS, 2009). Funding levels for these programs are modest. In FY2023, HCOP was funded at $16.0 million, COE at $28.42 million, AHEC at $47.0 million and Indian Health Service Programs at 3.9 million (HRSA, 2023e; TAGGS, 2022).

Efforts to Increase Representation in Pediatrics

Within pediatrics specifically, several programs and practices have been developed to recruit URiM students. Recruitment initiatives implemented by medical schools include increasing the representation of URiM students on admission committees, adopting a more holistic process to review applicants that considers experiences and attributes in addition to academic performance, and eliminating implicit biases (Weyand et al., 2020). Residency programs have made efforts to focus on URiM applicants through outreach via conferences and second-look programs, and institutions have provided fellows with travel rewards for interviews and conducted targeted improvement. However, few data are available on whether these efforts have improved representation among pediatric subspecialty fellows (Weyand et al., 2020).

There is also little evidence on individual institution or organization efforts on specific URiM recruitment in pediatrics. The Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, OH, increased the visibility of URiM faculty during recruitment and outside of the traditional interview process through outreach and social engagements with candidates. As a result of these efforts, the percentage of URiM residents in the program increased from a baseline of 5 percent in 2015 to 21 percent in the 2021 match (Hoff et al., 2021). As one of the newest subspecialties, pediatric hospital medicine has made concerted efforts to increase representation in their applicants by instituting a diversity and inclusion task force to review past recruitment practices for implicit bias or racism, conducting pre-interview events, highlighting opportunities for mentorship during the recruitment process, developing evidence-based best practice recommendations, and surveying matched and unmatched fellowship applicants to analyze effective URiM

recruitment strategies (Lopez and Raphael, 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated that virtual recruitment for pediatric subspecialty fellowships resulted in improvements in the diversity of application pools in part due to cost savings and less time lost from residency associated with not needing to travel to the fellowship site (Petersen et al., 2022).

Lopez and Fuentes-Afflick (2022) suggested the following workforce interventions to mitigate health inequities across pediatric subspecialty care, specifically by doing the following:

- Explore the obstacles that may pose unique challenges for individuals from URiM when considering a career in pediatric subspecialties, create programs to increase awareness of subspecialty careers, and promote policies to encourage entrance into these fields, such as loan forgiveness.

- Create, develop, and evaluate policies and programs to diversify the pediatric subspecialty workforce, including faculty recruitment of individuals from URiM groups and retention and leadership training.

- Expand and support career advancement through scholarship focused on reducing health inequities in all pediatric subspecialties.

- Implement strategies to diversify applicants to pediatric fellowship programs.

An important factor to recognize is that the pipeline for recruitment into pediatric subspecialties is the cohort of existing pediatrics residents who, in turn, draw from the existing cohort of medical students (Weyand et al., 2020). Therefore, a focus on efforts to increase diversity among pediatric subspecialists alone will not likely be able to increase representation broadly among the subspecialties; rather, more effort is likely needed to increase representation along the entire pipeline, especially at the earliest stages of career development. As noted by Fuentes-Afflick et al. (2022):

Although all specialties compete in a current zero-sum game to recruit [URiM] medical students into their specialty, we anticipate that efforts to enhance the diversity of medical students will have a positive impact on all specialties.

National Health Care Workforce Commission

There has been a long-standing awareness of the need to assess the supply of and demand for the health care workforce at the national level, but to date, little has been done. For example, the National Health Care Workforce Commission was established by the Patient Protection and Affordable

Care Act of 2010,14 with a structure similar to MedPAC and the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission. The purpose of the Commission was to advise Congress, the President, states, and localities on health care workforce supply and demand, and the related health workforce priorities, goals, and policies. However, Congress has not appropriated funds for the National Health Care Workforce Commission, preventing it from even meeting to discuss these issues (McDonough, 2021).

RETENTION

Although this chapter focused primarily on the factors that influence an individual to consider pursuing a career in a pediatric subspecialty, the retention of pediatric subspecialists is also important (the retention of pediatric physician–scientists is discussed in more detail in Chapter 6). Longevity as a pediatric subspecialist may be predicted by the personal or professional factors such as concerns surrounding financial considerations (e.g., educational debt and compensation) and clinician burnout, well-being, and job satisfaction. As discussed in Chapter 4, the number of first-year pediatric medical subspecialty fellows has been increasing over the past few decades (Macy et al., 2021). It is critical to support the current pediatric subspecialty workforce, while also considering ways to expand the pipeline and encourage future medical students to consider a pediatric subspecialty career.

Job Satisfaction

In a systematic review of physician satisfaction studies, Scheurer et al. (2009) found that pediatricians generally report higher satisfaction than other specialties. Studies of early and mid-career pediatricians found that more than 80 percent reported being satisfied with their career as a physician (Frintner et al., 2021b; Starmer et al., 2016). In addition, 95 percent of graduating pediatric residents surveyed in 2020 reported they would choose pediatrics again, a trend that has been consistent over the past 20 years (AAP, 2022). In a national longitudinal study of early to midcareer pediatricians, work satisfaction scale scores in 2012–2020 decreased slightly over time overall (Frintner et al., 2022). While 86 percent of pediatricians thought their work was personally rewarding, 37 percent were frustrated with their work situation. Over the study years, pediatricians with the strongest work satisfaction reported increased flexibility with work hours, support from colleagues, and time with patients while pediatricians who reported increased work hours and obstacles to balancing work and

___________________

14 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Section 5101.

personal responsibilities were more likely to report dissatisfaction (Frintner et al., 2022).

Clinician Burnout

The 2019 National Academies report Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout described burnout as “a syndrome characterized by high emotional exhaustion, high depersonalization (i.e., cynicism), and a low sense of personal accomplishments from work” (NASEM, 2019b, p. 1). Pediatric subspecialists may be at greater risk of burnout because of pressure to work longer hours (as a result of workforce shortages), and lower reimbursement compared with adult practice physicians (Kumar and Mezoff, 2020). As noted by Sallie Permar, Nancy C. Paduano Professor and chair of pediatrics at Weill Cornell Medicine, pediatrician-in-chief at New York Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, and professor of immunology and microbial pathogenesis at Weill Cornell Graduate School of Medical Sciences, in one of the committee’s public webinars:

The low [compensation] tied to the low reimbursement rate really does hold us back in terms of not only being able to recruit pediatricians throughout the pipeline from before medical school, in medical school, but also what I’ve found to be a problem also in preventing burnout and retaining our faculty in those roles. And we know that the burnout issue does face women and minorities more intensely.15

Students, clinicians, and faculty from URiM backgrounds may experience burnout due to what has been described as the “minority tax”—that is, “extra responsibilities placed on minority faculty in the name of efforts to achieve diversity” such as through disproportionate involvement in community outreach efforts or diversity initiatives (Rodriguez et al., 2015). This burden is often compounded by a lack of value assigned to these activities by their employers (such as in comparison to pursuing research), feelings of exclusion or isolation within their institutions, and a lack of mentors (Rodriguez et al., 2015; Williamson et al., 2021).

Although there are few studies of burnout specific to pediatric subspecialists, burnout has been documented in pediatric emergency medicine physicians (Gorelick et al., 2016; Gribben et al., 2019), pediatric hematology/oncology fellows (Moerdler et al., 2020), and pediatric nephrology fellows and faculty (Halbach et al., 2022). Only 43 percent of early career pediatricians (including subspecialists) reported having an appropriate work–life

___________________

15 The webinar recording can be accessed at https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/07-19-2022/the-pediatric-subspecialty-workforce-and-its-impact-on-child-health-and-well-being-webinar-1.

balance and 30 percent reported feeling burned out (Starmer et al., 2016). Burnout among pediatric subspecialists results in feeling less compassionate, a perception of higher stress and lower quality of life, and lower job satisfaction (Gorelick et al., 2016; Gribben et al., 2019; Halbach et al., 2022; Moerdler et al., 2020). During the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, several factors were significant predictors of increased burnout levels among pediatric subspecialists, including high levels of compassion fatigue, self-care not being a priority, and emotional depletion (Kase et al., 2022).

Administrative demands and electronic health record (EHR) documentation requirements have grown over time and can contribute to burnout in primary care (Frintner et al., 2021b; Gardner et al., 2019). Three-quarters of general pediatricians report EHR documentation as a major or moderate burden (Frintner et al., 2021b). Overhage and Johnson (2020) found that the mean total active time for EHR users per patient encounter across all pediatric subspecialties was 16 minutes, with 12 percent of this time after-hours, and ranged across subspecialties, from 14.5 minutes (generalists) to 30.8 minutes (rheumatologists). Using the assumption that an average pediatrician might care for 25 patients per day, Overhage and Johnson (2020) estimated that pediatricians spend 6 hours and 40 minutes using their EHR per day. This is slightly more than the average of 5.9 hours found for family medicine physicians’ EHR use per day (Arndt et al., 2017). This time-consuming documentation may contribute to pediatricians having or at least perceiving they have less time to address the needs of their patients.

Special Considerations for URiM

Discrimination in the workplace from co-workers, patients, families, and visitors has been documented among residents, practicing physicians, and faculty from URiM backgrounds (de Bourmont et al., 2020; Dyrbye et al., 2022; Filut et al., 2020; Lu et al., 2020; Nunez-Smith et al., 2009; Osseo-Asare et al., 2018; Serafini et al., 2020). Examples of discrimination include refusal of care by patients, racial epithets, and structural biases preventing advancement. However, the role of the work environment itself has not been extensively studied, particularly on how it may affect career trajectories, including burnout and retention. As noted by the American Medical Association (2021):

Concerted efforts toward increasing physician workforce diversity require an understanding of the workplace conditions that racially minoritized physicians face…[h]owever, little research exists documenting the experience of minoritized and marginalized physicians and how their experiences of racism may drive burnout, reduce well-being, and impact the practice of medicine.

Limited studies specific to pediatrics show similar concerns and the need to promote a more inclusive work environment (Kemper et al., 2020; March et al., 2018; Nfonoyim et al., 2020; Whitgob et al., 2016). Strategies to improve retention rates of URiM pediatricians will require a range of actions, but examining the culture of equity and inclusion in the workplace is a critical first step.

KEY FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS

Key Findings

Finding #5-1: Many factors can influence an individual’s choice to pursue subspecialty training, including:

- Exposure to the complete array of board-certified pediatric subspecialties and subspecialists (e.g., before medical school, during medical school, during residency);

- The presence of role models from subspecialty fields, particularly for URiM trainees (which may be scarce due to the small numbers of subspecialists);

- The length of fellowship training;

- The requirement for scholarly activity during fellowship;

- The debt burden of education and training;

- Relatively lower salaries, particularly for some pediatric medical subspecialties compared with general pediatricians in outpatient practice and adult medical subspecialists; and

- Lifestyle factors (e.g., work–life balance, job satisfaction, burnout).

Finding #5-2: ABP/ACGME requires that all pediatric subspecialty fellows participate in scholarly activity (see also Chapter 4).

Finding #5-3: While ABP provides a limited number of alternate, streamlined pathways for fellowship training, these pathways are primarily for trainees who are committed to careers in research. Similar pathways do not exist for trainees who are committed to careers in clinical practice.

Finding #5-4: There is no consensus among fellows, fellowship directors, and practicing subspecialists as to the optimal length of clinical and scholarly training in pediatric fellowship programs. Furthermore, there is a lack of evidence on the optimal duration and model of subspecialty training to prepare the subspecialty workforce to deliver high-quality care and to develop the foundational scientific evidence for that care.

Finding #5-5: Funding for pediatric residency programs may be derived from different sources, including Medicare, Medicaid, the CHGME program, and the THCGME program. However, more than half of pediatric training positions rely on CHGME funding.

Finding #5-6: The CHGME program was established to provide GME payments to freestanding children’s hospitals that only received minimal payments under the rules of Medicare GME. By contrast with Medicare GME, CHGME requires annual discretionary funding, and the payment levels are limited by the level of annual appropriations. On average, CHGME payments are less than half of the Medicare GME payment rate.

Finding #5-7: A 2014 IOM Committee concluded that the Medicare GME program is outdated and discourages training needed for modern health care, and recommended major reforms in the statutory payment formulas, accountability, and governance. These have not been implemented.

Finding #5-8: Female physicians tend to have lower starting salaries and earning potential than male physicians, which further exacerbates the financial disincentives in pursuing pediatric subspecialty careers because an increasingly larger portion of pediatricians are women.

Finding #5-9: Medical students from URiM backgrounds have higher levels of educational debt on average than other students.

Finding #5-10: Pediatricians are among the lowest paid specialists, even among primary care specialties.

Finding #5-11: While the Pediatric Specialty Loan Repayment Program was authorized at $30 million per year, it has not yet been fully funded at this level.

Finding #5-12: There are few examples of evidence-based models to inform the recruitment and retention needs of URiM physicians, specifically in pediatrics and subspecialties.

Finding #5-13: Efforts to date have not been effective in significantly increasing representation of URiM subspecialists.

Finding #5-14: There is minimal understanding of the impact of the work environment on URiM burnout and retention.

Conclusions

Conclusion #5-1: The current model of education and training for pediatric medical subspecialists focuses on the creation of subspecialists who demonstrate competency in all aspects of academic careers, including clinical care, research, and education (see also Chapter 4).