The Future Pediatric Subspecialty Physician Workforce: Meeting the Needs of Infants, Children, and Adolescents (2023)

Chapter: 4 The Pediatric Health Care Workforce Landscape

4

The Pediatric Health Care Workforce Landscape

A range of practitioners are responsible for the health care of children. General pediatricians and pediatric subspecialty physicians focus exclusively on the health and development of infants, children, adolescents, and young adults. General pediatricians often form continuous relationships with children and their families to support their development into adulthood with unique understandings of all the factors that affect their well-being. Pediatric subspecialty physicians often also have long-term relationships with patients, especially those children who have chronic illness. In addition, many other health and social care practitioners provide high-quality care and services for children and youth and are critical to the pediatric health care workforce, especially for team-based care.

This chapter focuses primarily on ABP-certified pediatric subspecialty physicians, including their demographics and work profiles. Additionally, a brief overview of general pediatricians and many of the other health care professionals that provide pediatric care is presented to give a sense of the broader workforce that cares for children and often work together with pediatric subspecialty physicians. Chapter 7 further explores the interface between primary care clinicians and pediatric subspecialty physicians.

THE PATHWAY TO BECOMING A PEDIATRIC SUBPECIALTY PHYSICIAN

The design and maintenance of the pathway to becoming a certified pediatric subspecialist in the United States is a joint responsibility largely shared by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education

(ACGME) and the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) or the American Osteopathic Board of Pediatricians (AOBP).

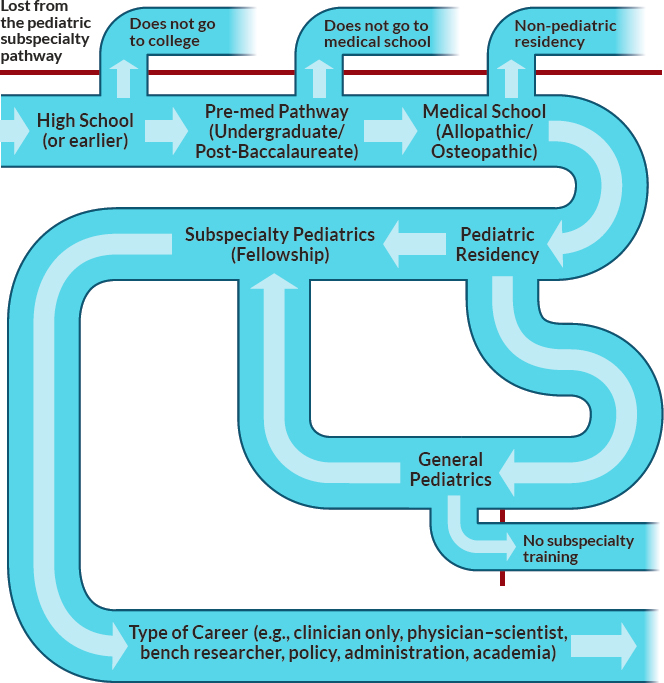

The committee recognizes that individuals need to make multiple decisions in the course of the pathway to becoming a pediatric subspecialist. The typical pediatric subspecialty workforce pathway, and key decision points, are exemplified in Figure 4-1. (For more on the specific factors along this pathway that influence an individual’s choice to pursue pediatric subspecialty training throughout this pathway, see Chapter 5.)

The committee first recognizes that life experiences even before high school can contribute to the choice to pursue pediatrics and ultimately, subspecialty training. In general, a student proceeds from high school, to college, and then medical school. Potential subspecialty trainees are lost at each of these points if they do not choose to pursue higher education

NOTE: This figure does not reflect all the alternative pathways and combined training programs available for some pediatric subspecialties.

SOURCE: Committee generated.

or enter a non-pediatric residency program. Typically, fourth year medical students with an interest in pursuing pediatrics apply to pediatric residency programs through the National Residency Match Program (NRMP), but some residents will be accepted into fellowship training programs outside of the NRMP process. (See discussion later in this chapter.) After choosing to enter a pediatric residency, the trainee next needs to make a choice about pursuing subspecialty training as opposed to remaining a general pediatrician. Figure 4-1 recognizes that individuals who choose to pursue general pediatrics may later return for subspecialty training (as opposed to entering a fellowship immediately after residency). Finally, pediatric subspecialists need to make decisions about the type of career they would like to pursue, including as a clinician, physician–scientist, bench researcher, policy maker, administrator, and/or educator. Many subspecialists participate in more than one of these focus areas. The following sections give a brief overview of the education and training requirements along this pathway.

Overview of Education and Training Requirements

As of May 2023,1 in addition to a number of basic requirements regarding the structure and content of residency programs, ABP-certified pediatric residency programs are required to have faculty members with subspecialty board certification in adolescent medicine, developmental-behavioral pediatrics, neonatal-perinatal medicine, pediatric critical care medicine, pediatric emergency medicine, and subspecialists from at least five other distinct pediatric medical disciplines (ACGME, 2022a). Exposure to a variety of pediatric subspecialists may help influence decisions to enter those career paths.

As described in Chapter 1, requirements for subspecialty training evolved over the past several decades. In the late 1980s, an expectation for in-depth research experiences became a requirement (Stevenson et al., 2014). In 1996, the Federation of Pediatric Organizations issued a policy statement emphasizing that the goal of fellowship training was to create academic pediatricians by fostering competence in clinical care, education and research (FOPO, 2001). The statement included guidelines for fellowship, including the development of clinical skills, opportunities for scholarly activities, training to ensure graduates are effective teachers, and the presence of mentors. In 2004, the Subspecialties Committee of ABP affirmed this commitment to creating academic subspecialists and noted:

___________________

1 As of the writing of this report, several changes have been proposed for residency training. However, those changes have not been approved or finalized.

In discussing optional pathways for fellowship training, the question was raised whether a “third-tier,” clinical-only, fellowship training pathway should be established…the Subspecialties Committee concluded that additional clinical training in lieu of a scholarly activity experience was not consistent with the principal goal of fellowship training being preparation for a career in academic pediatrics. (ABP, 2004, p.10)

Today, with the exception of pediatric hospital medicine, ACGME requires all pediatric subspecialty fellowships to be 36 months in length with a requirement for scholarly activity included (ACGME, 2022a). Although there are multiple, specific alternate training pathways for fellows interested in a career focused on research, no similar pathway for a career focused on clinical care remains. For more on the research requirements of fellowship and alternate training pathways, see Chapter 5.

Preparation of Pediatric Subspecialists to Care for Today’s Children

Entrustable professional activities (EPAs) are the “observable, routine activities that a pediatric subspecialist should be able to perform safely and effectively to meet the needs of their patients” (ABP, 2023a). The ABP worked with the pediatrics community to develop a core set of seven EPAs (for all subspecialties), with three or more additional EPAs specific to the subspecialty. Similarly, EPAs exist for general pediatrics. However, questions have been raised about the preparation of the pediatric subspecialty workforce to fully meet the needs of today’s children in light of their evolving health needs (see Chapter 2).

In part, lack of preparation in some key areas may lie in residency training. As noted by Hilgenberg et al. (2021): “While the ACGME and [ABP] periodically publish residency program curricular changes, programs have limited resources and time in which to design, adapt, individualize, and/or implement changes and may struggle to respond, resulting in curricular gaps.” In fact, Hilgenberg et al. (2021) found that 59 percent of graduating pediatrics residents planning for careers in primary care and 49 percent of graduating pediatrics residents planning for careers in subspecialty care desired additional clinical training. Among program directors and associate program directors, 21 percent identified additional clinical training as most needed in their curricula. Some smaller studies have suggested specific training needs in residency for cultural competence (Rule et al., 2018) and the care of working with transgender and gender non-conforming patients (Barber Doucet et al., 2021). Furthermore, pediatric residents and subspecialty fellows may not be fully prepared to address or refer for mental health and substance use disorders (Green et al., 2019, 2022). For example, while nearly two-thirds of pediatric subspecialty fellows believe they should

be responsible for the emotional and mental health concerns of children with chronic medical conditions, few feel competent to do so (Green et al., 2022). Just 53 percent of graduating general pediatrics residents from 2015 to 2018 demonstrated achieving the level of competence for behavioral and mental health care needed to provide care independently (Schumacher et al., 2020). Hadland and colleagues (2016) suggested that all pediatric clinicians should be trained to prevent and treat addiction, and that “residency programs should develop specific training in [medication-assisted treatment] and offer robust clinical experiences in youth addiction medicine” (Hadland et al., 2016).

GENERAL PEDIATRICIANS

The following section gives a brief overview of actively practicing general pediatricians, residents in general pediatrics, and pediatric residency programs.

Demographics

As of July 2023, 56,882 pediatricians are actively maintaining their certification with ABP in general pediatrics only (not including those who are actively maintaining certification in general pediatrics as well as certifications in one or more pediatric subspecialties) (ABP, 2023b). However, this number does not recognize pediatricians who are trained and practicing, but not certified by ABP. For example, while most physicians with degrees as doctors of osteopathic medicine (D.O.s) pursue primary specialty certification through ABP, a number of D.O.s pursue primary specialty certification through AOBP. As of December 31, 2017, 648 D.O. pediatricians had active AOBP specialty board certificates, with 42 D.O.s certified in a pediatric subspecialty (Wieting et al., 2018). An analysis by the Association of American Medical Colleges of the American Medical Association Physician Masterfile estimated that in 2021, there were 60,305 actively practicing general pediatricians in the United States, or 1,720 individuals under age 24 per pediatrician (AAMC, 2023). This estimate includes physicians who were not certified by ABP, but who indicated that pediatrics was their primary area of work.

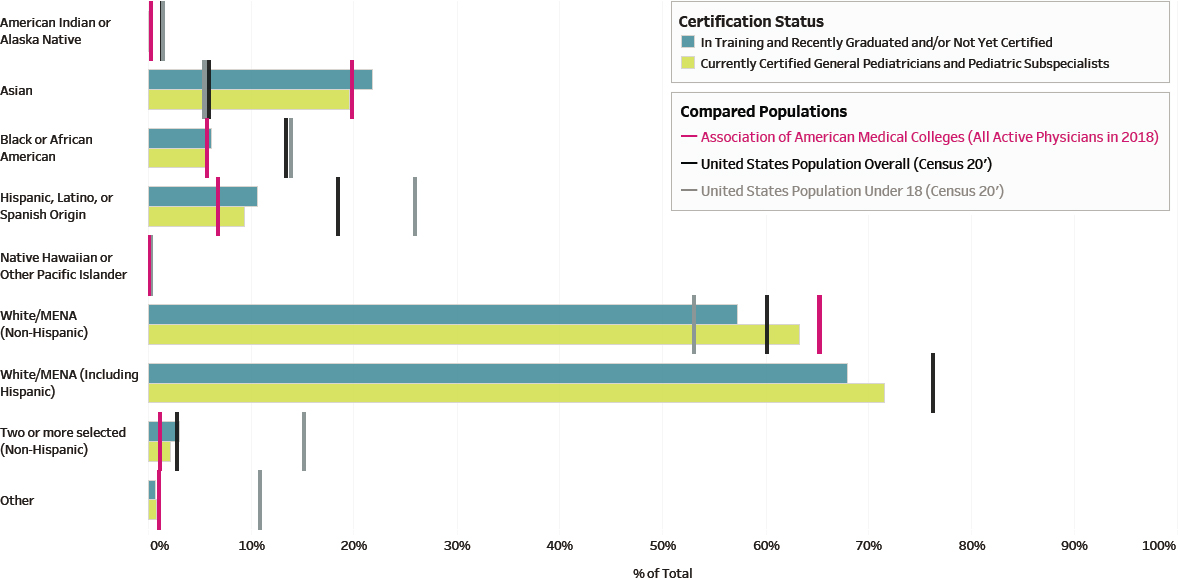

Among pediatricians who are currently maintaining their certification in general pediatrics, nearly 81 percent are American medical graduates and 71 percent are female (ABP, 2023c). As shown in Figure 4-2, general and subspecialty pediatricians are predominantly White/Non-Hispanic, but those who are in training, recently graduated, and/or not yet certified are increasingly diverse. (See later in this chapter for more specific demographic data on the pediatric subspecialties.)

NOTE: MENA = Middle East and North Africa

SOURCE: ABP, 2023d. Reprinted with permission from the American Board of Pediatrics.

Pediatric Residents and Training Programs

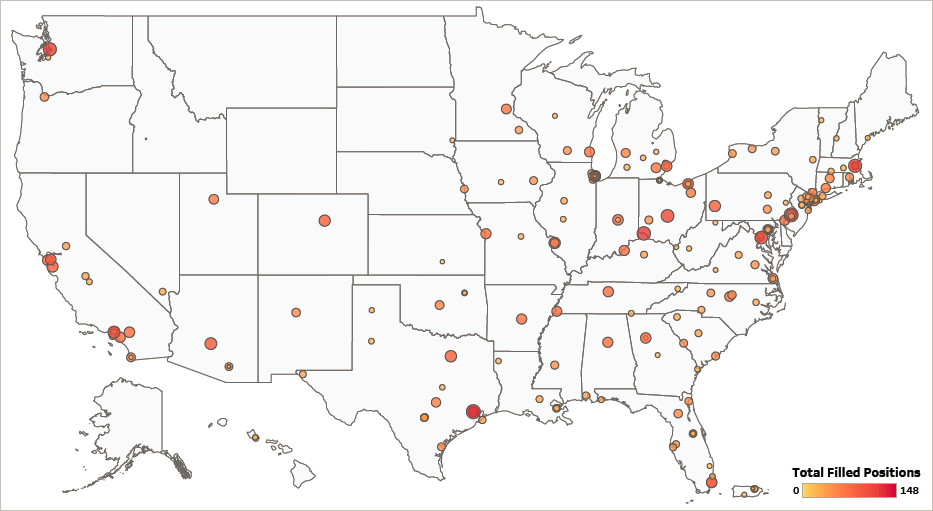

In 2022, there were 11,930 residents (including all years of residency and residents in combined programs and alternate pathways) in general pediatrics (an 11.6 percent increase over the previous 10 years) (ABP, 2023e). Eighteen percent of these residents were training in a combined program or alternate pathway. Twenty-one percent2 of the 9,801 general pediatrics residents not in combined programs or alternate pathways are international medical graduates. Data from 20193 show that 14.54 percent of residents not in a combined program or alternative pathway had a D.O. (ABP, 2023e). Like currently certified pediatricians, the majority of first year general pediatrics residents (73 percent) are female (up from 70.2 percent in 2008) (ABP, 2023f). Pediatrics is second only to obstetrics and gynecology for the largest percentage of active female residents (ACGME, 2021). This is significant as female pediatricians are more likely to work part time than male pediatricians (Freed et al., 2016, 2017). In 2022, 53.1 percent of all general pediatrics residents were White; 21.4 percent were Asian; 7.5 percent were Hispanic, Latino, or of Spanish origin; and 6.3 percent were Black or African American (ABP, 2023g). Nearly 19 percent of residents were identified as having a background that is underrepresented in medicine (URiM). The number of residency positions in pediatrics increases every year, and those positions are rarely unfilled (see Table 4-1). Residency and fellowship training programs have a wide geographic distribution, but with large areas of the country not being represented (see Figure 4-3).

PEDIATRIC SUBSPECIALTY FELLOWS

As noted earlier, some pediatrics residents pursue fellowship training in more specialized areas of pediatric care beyond the required training for general pediatrics. This section includes a discussion of pediatric fellows, including their basic demographics, and focuses primarily on the ABP-certified subspecialties.

___________________

2 Calculated on the ABP dashboard by choosing to analyze by medical school location and choosing “categorical pediatrics” under the residency training pathway for all training levels and all training program locations (ABP, 2023e).

3 2019 is the most recent year for which data on degree are available.

4 Calculated on the ABP dashboard by choosing to analyze by medical degree and choosing “categorical pediatrics” under the residency training pathway for all training levels and all training program locations (ABP, 2023e).

TABLE 4-1 Postgraduate Year 1 (PGY-1) Pediatrics (Categorical) Positions Offered and Percentage Filled, 2018–2023

| Year | PGY-1 Positions Offered | Percentage Filled |

|---|---|---|

| 2023 | 2,986 | 97.1% |

| 2022 | 2,942 | 97.2% |

| 2021 | 2,901 | 98.6% |

| 2020 | 2,864 | 98.2% |

| 2019 | 2,847 | 97.6% |

| 2018 | 2,768 | 97.9% |

NOTES: This table does not include positions offered through combined training programs or alternate pathways. It also may underestimate the percentage of positions filled as it does not include matches made outside the NRMP process.

SOURCES: NRMP, 2022, 2023a.

Demographics

In 2023, NRMP reported that there were 860 accredited programs in the 15 ABP-certified pediatric medical specialties participating in the match, offering 1,786 positions, ranging from 23 positions in child abuse pediatrics to 288 positions in neonatal-perinatal medicine (NRMP, 2023b). An important note is that while most fellows match to their programs through NRMP, some fellows will be accepted into accredited programs outside of the formal match process (ABP, 2023i; Freed and Wickham, 2023; Macy et al., 2021). As shown in Table 4-2, average position fill rates for accredited programs both through the formal NRMP process and the final fill rate (as calculated by ABP) show significant variation across pediatric subspecialties. These data show the average fill rate for each ABP subspecialty over the time period from 2014 to 2022. Given the small numbers for some subspecialties, fill rates may vary each year—therefore, examination of the average over a period of time presents a more complete picture of the challenges some subspecialties experience in filling available positions. Overall, however, these numbers and fill rates may not reflect the need for each of those subspecialties, and many factors influence the decision to pursue subspecialty training (see Chapter 5). For example, a high fill rate may not reflect the need for even more positions to meet the health care needs of children, and a low fill rate may reflect too many positions being available.

In addition to the variation in fill rates, as seen in Figure 4-4, there is wide variation in the number of first-year fellows by subspecialty (ABP, 2023j). Some subspecialties have had a steady increase in the number of first-year fellows (particularly among the more procedural subspecialties), while others have remained relatively stable (particularly among the

SOURCE: Modified from ABP, 2023h. Data retrieved by ABP based on academic year snapshot data from the ACGME. Reprinted with permission from the American Board of Pediatrics.

TABLE 4-2 ABP-Certified Subspecialty by Average NRMP-Reported Fellowship Match Fill Rate and Average ABP-Calculated Final Fill Rate, 2014–2022

| Pediatric Subspecialty | NRMP-Reported Fill Rate | ABP-Calculated Final Fill Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Pediatric Gastroenterology | 94.1% | 108.3% |

| Pediatric Hospital Medicine | 98.6% | 107.9% |

| Pediatric Cardiology | 96.0% | 103.9% |

| Pediatric Critical Care Medicine | 96.7% | 103.8% |

| Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine | 91.9% | 103.4% |

| Pediatric Emergency Medicine | 98.9% | 103.3% |

| Adolescent Medicine | 78.9% | 98.6% |

| Pediatric Hematology/Oncology | 90.0% | 97.9% |

| Pediatric Pulmonology | 63.0% | 86.9% |

| Pediatric Endocrinology | 64.7% | 86.0% |

| Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics | 64.3% | 82.8% |

| Pediatric Rheumatology | 64.2% | 79.2% |

| Pediatric Infectious Diseases | 57.0% | 79.0% |

| Child Abuse Pediatrics | 58.7% | 69.0% |

| Pediatric Nephrology | 53.3% | 65.7% |

NOTE: Final fill rates may be over 100 percent, as some programs may ultimately accept more fellows than the number of positions reported in the NRMP process.

SOURCES: ABP, 2023i; NRMP, 2023b.

subspecialties that typically involve fewer procedures). The total number of first-year fellows has grown by more than 27 percent between 2012 and 2022, in part due to the establishment of certification for pediatric hospital medicine in 2019 (ABP, 2023k).

Similar to general pediatrics fellows, 12.6 percent5 of first-year subspecialty fellows (in both U.S. and Canadian programs) in 2022 had a D.O. degree and 26.9 percent were international medical graduates (ABP, 2023k). Additionally, subspecialty fellows are predominantly female (70.3 percent of first-year fellows in 2022, up from 59.8 percent in 2008) and nearly 17 percent of residents were identified as having a URiM background (ABP, 2023k,l). (See later in this chapter for the percentage of women and

___________________

5 Calculated on the ABP dashboard by choosing to analyze by medical degree and choosing “all” under the “training program location” filter (ABP, 2023k).

NOTES: Pediatric hospital medicine fellowships were first accredited and reported in 2020. NRMP match rate data reflect the positions offered and accepted within the NRMP match process and do not account for fellows who enroll in programs outside of the formal match process.

SOURCE: ABP, 2023j. Reprinted with permission from the American Board of Pediatrics.

the percentage of individuals from URiM backgrounds by subspecialty for pediatric subspecialty fellows as compared with practicing pediatric subspecialists.)

ABP Co-Sponsored Subspecialties, Alternative Pathways, and Combined Training Programs

As noted in Chapter 1, some pediatric subspecialists are certified by co-sponsoring ABMS boards, by the American Osteopathic Board of Pediatrics, or via several combined training programs and non-standard pathways for subspecialization. Each of these pathways have different education and training requirements and procedures, but they have not been extensively studied as a whole. In 2023, NRMP reported on the availability of first-year fellowship positions in the following subspecialties certified via nonstandard pathways and combined training programs:

- Pediatrics—Medical Genetics: 25 positions

- Pediatrics—Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation: 4 positions

- Pediatrics—Psychiatry/Child Psychiatry: 26 positions

- Child Neurology—177 positions

- Medicine—Pediatrics: 392 positions

- Pediatrics—Anesthesiology: 7 positions

- Pediatrics—Emergency Medicine: 9 positions (NRMP, 2023a).

Pediatric Surgical Subspecialists

The number of pediatric surgery training programs has increased, and such programs are considered among the most competitive (Alaish et al., 2020; Farooqui et al., 2023; Yheulon et al., 2019). Several ABMS boards offer subspecialty certificates in pediatric surgical subspecialties. For example, the American Board of Thoracic and Cardiac Surgery certifies congenital heart surgeons to care for infants, children, and adolescents with congenital, acquired, or end-stage heart disease (Surgical Advisory Panel et al., 2014). While there may not be formal subspecialty certification, several other surgical specialties (e.g., ophthalmology, orthopedic surgery, and plastic surgery) offer additional training (including fellowships) in the care of pediatric patients (Surgical Advisory Panel et al., 2014). However, concerns have been raised about the quality of pediatric surgical training, resulting in calls for improvements in training and certification (Alaish and Garcia, 2019; Alaish et al., 2020; Drake et al., 2017; Farooqui et al., 2023), such as through the American Pediatric Surgical Association’s Right Child/Right Surgeon initiative (Alaish et al., 2020).

ACTIVELY PRACTICING PEDIATRIC SUBSPECIALTY PHYSICIANS

As shown in Table 4-3, the number of ABP-certified pediatric subspecialists maintaining certification varies widely by subspecialty area (ABP, 2023m). Similarly, the number of physicians trained in subspecialties co-sponsored by ABP but certified by another ABMS board are shown in Table 4-4.

The following sections will give an overview of the work profiles and demographics of actively practicing pediatric subspecialists (primarily those physicians practicing in one of the 15 ABP-certified subspecialties).

TABLE 4-3 Numbers of Pediatric Subspecialists Ever Certified by ABP and Numbers Maintaining Certification by Subspecialty

| Subspecialty | Ever Certified | Maintaining Certification |

|---|---|---|

| Adolescent Medicine | 836 | 580 |

| Child Abuse Pediatrics | 425 | 363 |

| Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics | 1,043 | 803 |

| Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine | 7,871 | 5,319 |

| Pediatric Cardiology | 4,117 | 3,096 |

| Pediatric Critical Care Medicine | 3,689 | 3,128 |

| Pediatric Emergency Medicine | 3,493 | 3,017 |

| Pediatric Endocrinology | 2,218 | 1,508 |

| Pediatric Gastroenterology | 2,232 | 1,882 |

| Pediatric Hematology/Oncology | 4,231 | 2,929 |

| Pediatric Hospital Medicine | 2,542 | 2,537 |

| Pediatric Infectious Diseases | 1,876 | 1,368 |

| Pediatric Nephrology | 1,199 | 729 |

| Pediatric Pulmonology | 1,585 | 1,254 |

| Pediatric Rheumatology | 626 | 508 |

| Total | 37,983 | 29,021 |

NOTES: Data are as of June 14, 2023. Calculated on the ABP dashboard by choosing to analyze each certification area (i.e., subspecialty) by “all, no breakout.”

SOURCE: ABP, 2023m.

TABLE 4-4 Numbers of Pediatric Subspecialists Co-Sponsored by ABP and Ever Certified by other ABMS boards and Numbers Maintaining Certification by Subspecialty

| Subspecialty | Ever Certified | Maintaining Certification |

|---|---|---|

| Hospice and Palliative Medicine | 479 | 414 |

| Medical Toxicology | 51 | 34 |

| Sleep Medicine | 394 | 350 |

| Sports Medicine | 416 | 348 |

| Transplant Hepatology | 179 | 153 |

| Total | 1,519 | 1,299 |

NOTES: Data are as of June 14, 2023. Calculated on the ABP dashboard by choosing to analyze each certification area (i.e., subspecialty) by “all, no breakout.”

SOURCE: ABP, 2023m.

Work Profiles and Settings

Based on data collected in 2018–2022 from maintenance of certification enrollment surveys, 89 percent6 of respondents from the ABP-certified subspecialties indicated that they worked full time (84.6 percent of women and 93.9 percent of men)7 (ABP, 2023n). Eighty-five percent reported working 40 or more hours a week, and 24 percent reported working 60 or more hours a week.7 A larger percentage of men reported working more than 50 hours per week as compared with women.8 Given that women represent an increasing proportion of the subspecialty workforce, these practice patterns may have implications for future workforce planning. That is, if women work fewer hours, more subspecialists may be needed to provide the same amount of care. (See Chapter 5 for more on lifestyle influences on careers for female subspecialists.)

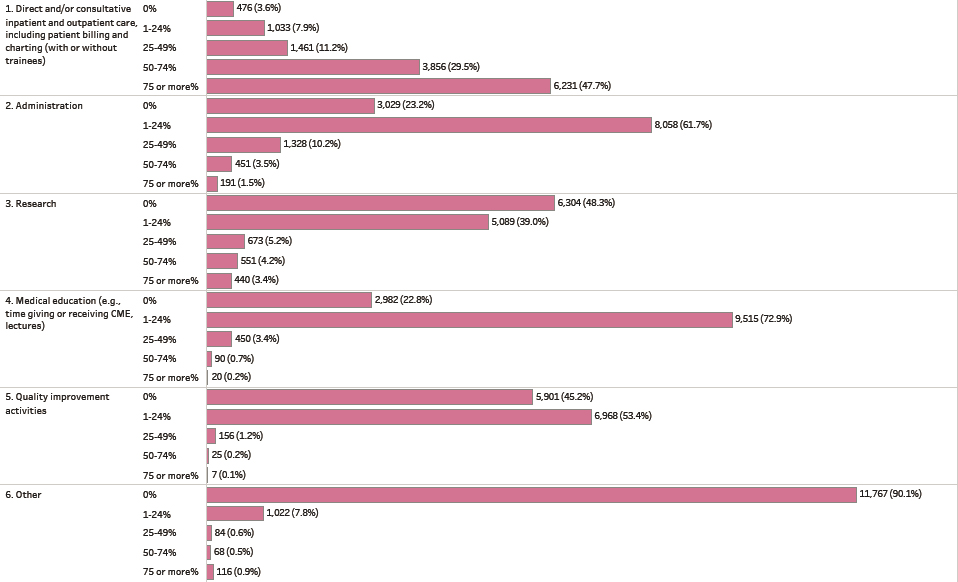

As seen in Figure 4-5, ABP-certified pediatric subspecialists report spending the bulk of their professional time on direct or consultative patient care. Less than 8 percent of subspecialists reported spending more than 50 percent of their time doing research, and nearly half (48.3 percent) reported not being involved in any research activities (ABP, 2023n).

___________________

6 Calculated on the ABP dashboard by choosing “none (no breakout)” under “select to crosstab results” and by choosing the 15 ABP-certified subspecialties under “GP/subspecialty certification” filter (ABP, 2023n).

7 Calculated on the ABP dashboard by choosing “gender” under the “select to crosstab results” filter and by choosing the 15 ABP-certified subspecialties under “GP/subspecialty certification” filter (ABP, 2023n).

8 Calculated on the ABP dashboard by choosing “overall specialty status” under the “select to crosstab results” filter and by choosing the 15 ABP-certified subspecialties under “GP/subspecialty certification” filter (ABP, 2023o).

NOTE: CME = continuing medical education.

SOURCE: ABP, 2023n. Reprinted with permission from the American Board of Pediatrics.

ABP-certified pediatric subspecialists are most likely to have their primary work setting in a medical school or parent university (32 percent), a non-government hospital or clinic (22 percent), or a pediatric or multispecialty group practice (26 percent) (ABP, 2023o).8 The majority (78.5 percent) of subspecialists report some form of academic faculty appointment. One setting of care that is unique to children are children’s hospitals. As noted by Colvin and colleagues (2016a), “[c]hildren’s hospitals (whether freestanding or within a general hospital) provide a wide range of pediatric specialty care or are dedicated solely to specific disease states (e.g., pediatric cancer).” The authors noted that while children’s hospitals only accounted for 3.4 percent of all hospitals, they represented about one third of all pediatric hospital discharges and almost half (42.5 percent) of discharges for children with medical complexity and high severity of illness (Colvin et al., 2016b).

Geographic Distribution

Most ABP-certified pediatric subspecialists report working primarily in an urban setting (76 percent), with 20 percent practicing primarily in suburban settings and 3 percent primarily in rural settings9 (ABP, 2023o). Comparatively, approximately 19 percent of children (aged 17 years and younger) live in rural areas (KidsData, 2018). Among pediatricians who completed training in 2012 through 2021, nearly 31 percent of subspecialists (on average) report practicing in a medically underserved area (AAMC, 2022a). Furthermore, on average, nearly 60 percent of subspecialists are practicing in the state where they completed their training (AAMC, 2022b). As noted in Chapter 2, regionalization of these subspecialists is logical “given that highly specialized physicians would be unlikely to have enough patients to attend to in any single community” and that access to technologies and other resources for care will be more available in centralized care centers (Gans et al., 2013). According to Rimsza et al. (2018):

There are many factors besides supply that can affect the geographic distribution of subspecialists, including location of training [see Figure 4-3], financial viability of practice location, limited availability of other physicians to share call and provide consultative services, and lack of employment opportunities for other family members. In addition, a subspecialist who is interested in teaching and research is likely to have limited opportunities to pursue these interests outside of an urban academic center.

___________________

8 Calculated on the ABP dashboard by choosing “overall specialty status” under the “select to crosstab results” filter and by choosing the 15 ABP-certified subspecialties under “GP/subspecialty certification” filter (ABP, 2023o).

9 Total is less than 100 percent due to rounding.

For all types of physicians, there are significant associations between physician practice location and their racial and ethnic composition. Physicians identifying as American Indian, Alaska Native, or Hawaiian/Pacific Islander; black or African American; and/or Hispanic/Latino are more likely to practice in impoverished areas, and areas federally designated as medically underserved or experiencing health professional shortages (Xierali et al., 2014). In general, URiM trainees are more likely to establish a practice in underserved areas (Walker et al., 2012).

Race, Ethnicity, and Sex

There is some evidence that racial concordance between patient and physician is associated with reduction in health disparities and increased patient satisfaction (Alberto et al., 2021; Greenwood et al., 2020; Takeshita et al., 2020). However, the pediatric workforce does not reflect the diversity of its patients (Lopez and Fuentes-Afflick, 2022; Mehta et al., 2019). In 2021, 26 percent of children under age 18 were Hispanic, Latino, or of Spanish origin (as compared with 6.2 percent of certified general pediatricians and 5.8 percent of certified pediatric subspecialists);10 14 percent of children under age 18 were Black or African American (as compared with 6.4 percent of certified general pediatricians and 4.4 percent of certified pediatric subspecialists) (ABP, 2023p,q). Although the pediatrics workforce overall does not reflect the diversity of U.S. children, recently graduated and/or not yet certified pediatricians are slightly more diverse than currently certified general pediatricians and subspecialists (see Table 4-5).

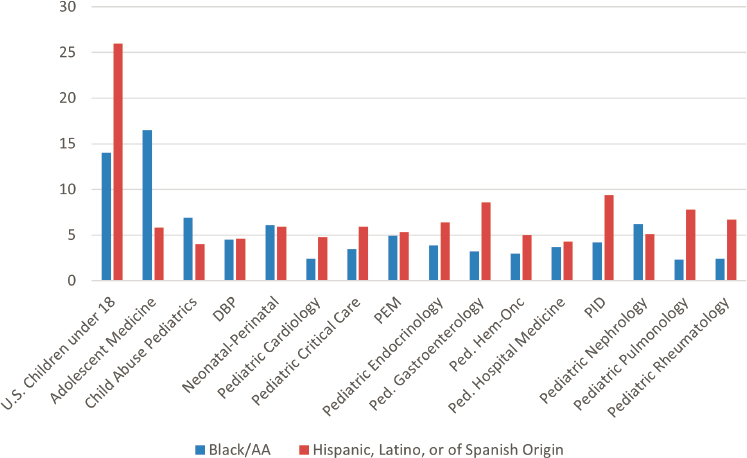

As shown in Figure 4-6, similar patterns are seen within the individual pediatric medical subspecialties. The pediatric subspecialty workforce has as few as 2.3 percent of pediatric pulmonologists and 2.4 percent of pediatric cardiologists and pediatric rheumatologists identifying as Black or African American and 4.0 percent of child abuse specialists identifying as Hispanic, Latino, or of Spanish descent (ABP, 2023q).11

Overall, pediatric medical subspecialists are becoming increasingly female and from URiM backgrounds. As seen in Table 4-6, the vast majority of subspecialties show an increased percentage of women and individuals who are URiM among subspecialty fellows as compared with certified subspecialists.

___________________

10 Percentages for certified general pediatricians and certified subspecialists were calculated on the ABP dashboard by choosing “certification status with trainee type” under the “crosstab” filter and by choosing “no merging” under the “race and ethnicity groupings” filter (ABP, 2023q).

11 Calculated on the ABP dashboard by choosing “GP/subspecialty” under the “crosstab” filter and by choosing “no merging” under the “race and ethnicity groupings” filter (ABP, 2023q).

TABLE 4-5 Estimated Percentages of Race and Ethnicity Groups and URiM Status by Certification Status

| Certification Status | Black or African American | Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish Origin | White | URiM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recently Graduated and/or Not Yet Certified | 7.0 | 7.7 | 49.5 | 18.7 |

| Certified General Pediatricians | 6.4 | 6.2 | 61.0 | 15.9 |

| Certified Pediatric Subspecialists | 4.4 | 5.8 | 60.6 | 13.0 |

NOTES: Counts for URiM include categories of: American Indian or Alaska Native; Black or African American; Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish Origin; and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander. Individuals who indicated two or more race and ethnicity categories are not included in URiM.

Percentages for Black or African American; Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish Origin, and White were calculated on the ABP dashboard by choosing “certification status with trainee type” under the “crosstab” filter and by choosing “no merging” under the “race and ethnicity groupings” filter. For URiM, “merge to display URIM category” was chosen under the “race and ethnicity groupings” filter.

SOURCE: ABP, 2023q.

MODELING THE FUTURE SUBSPECIALTY WORKFORCE

In a committee webinar on November 2, 2022,12 Laurel Leslie, vice president of research for ABP, and Colin Orr, assistant professor in the Division of General Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, gave a presentation on a workforce model under development to estimate the future supply of the pediatric subspecialty physician workforce. The model is a partnership between ABP and The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research (AMSPDC, 2020). The model will use historical data for the supply of 14 of the ABP-certified subspecialties,13 and then apply different scenarios to see what the impact would be on future supply. The model intends to look not just at absolute numbers, but also to consider changing work profiles (e.g., time spent in direct clinical care), geography (at multiple levels), age, and gender. The model is unique from other forecasting models in that it has separate forecasts for each subspecialty. The model does not make any assumptions about increased use of

___________________

12 The webinar recording can be accessed at https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/11-02-2022/the-pediatric-subspecialty-workforce-and-its-impact-on-child-health-and-well-beingwebinar-3.

13 Hospital medicine was excluded due to a lack of sufficient data.

NOTES: DBP = developmental-behavioral pediatrics; Hem/Onc = hematology/oncology; PEM = pediatric emergency medicine; PID = pediatric infectious diseases. Percentages for the subspecialties were calculated on the ABP dashboard by choosing “GP/subspecialty” under the “crosstab” filter and by choosing “no merging” under the “race and ethnicity groupings” filter.

SOURCES: ABP, 2023p,q.

telehealth or advanced practice providers (e.g., advanced practice registered nurses [APRNs], physician assistants). Early results presented at the webinar indicate that growth (e.g., in absolute numbers, number of clinicians per 100,000 children) varies by subspecialty. Papers on the results of modeling by subspecialty are scheduled to be made public in 2023.

PRIMARY CARE CLINICIANS

Apart from pediatricians, a variety of primary care clinicians provide care for children, particularly in team-based models of care. These clinicians include nurses, physician assistants, and physicians (e.g., adult subspecialty physicians who care for children, family medicine physicians). Information on the use of primary care clinicians (apart from pediatricians) for subspecialty care is not well known.

TABLE 4-6 Pediatric Subspecialty Fellows in U.S. Fellowship Programs and Pediatricians Maintaining Certification in ABP-Certified Subspecialties by Sex and URiM Status, 2022

| Subspecialty | Percentage Women | Percentage URiM* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fellows | Certified | Fellows | Certified | |

| Adolescent Medicine | 79.6 | 76.8 | 27.9 | 26.8 |

| Child Abuse Pediatrics | 77.6 | 83.0 | 18.2 | 15.9 |

| Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics | 89.7 | 76.6 | 20.8 | 14.0 |

| Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine | 72.4 | 58.3 | 20.1 | 14.8 |

| Pediatric Cardiology | 53.5 | 40.6 | 11.0 | 9.2 |

| Pediatric Critical Care Medicine | 65.2 | 48.6 | 13.0 | 12.0 |

| Pediatric Emergency Medicine | 67.2 | 60.8 | 18.0 | 12.5 |

| Pediatric Endocrinology | 80.3 | 73.6 | 19.4 | 14.2 |

| Pediatric Gastroenterology | 69.4 | 52.3 | 20.5 | 14.7 |

| Pediatric Hematology/Oncology | 68.5 | 60.3 | 13.0 | 10.0 |

| Pediatric Hospital Medicine | 73.1 | 72.8 | 16.5 | 11.0 |

| Pediatric Infectious Diseases | 68.9 | 58.8 | 17.4 | 17.8 |

| Pediatric Nephrology | 70.1 | 62.5 | 14.6 | 12.9 |

| Pediatric Pulmonology | 65.5 | 49.2 | 17.7 | 13.1 |

| Pediatric Rheumatology | 76.9 | 70.7 | 18.7 | 12.2 |

| Overall | 68.8 | 58.8 | 16.8 | 13.0 |

NOTES: Data for specialists maintaining certification reflect those who answered the survey as a part of maintenance of certification from 2018 to 2022, and are estimates given the response rate of 60.5 percent. The data overall do not include information regarding the small group of subspecialists who have completed fellowship training but are not yet certified. Counts for URiM include categories of: American Indian or Alaska Native; Black or African American; Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish Origin; and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander. Individuals who indicated two or more race and ethnicity categories are not included in URiM.

URiM percentages for fellows were calculated on the ABP dashboard by examining each subspecialty by choosing “merge to display URiM category” under the “race and ethnicity groupings” filter. The overall percentage was calculated by choosing “all” under the “subspecialty selection” filter (ABP, 2023l).

URIM percentages for certified subspecialists were calculated on the ABP dashboard by choosing “GP/subspecialty” under the “crosstab” filter and choosing “URiM” under the “race and ethnicity” filter and choosing “merge to display URiM category” under the “race and ethnicity groupings” filter. The overall percentage was calculated by choosing “certification status” under the “crosstab” filter (ABP, 2023q).

Female percentages for fellows were calculated on the ABP dashboard by examining each subspecialty by choosing to analyze data by gender and choosing “all” for the training level filter and choosing “U.S. programs” under the training location filter (ABP, 2023r). The overall percentage was calculated by choosing to analyze data by gender and choosing “all” for the training level filter and choosing “U.S. programs” under the training location filter (ABP, 2023k).

Female percentages calculated on the ABP dashboard by examining each subspecialty and by choosing to analyze data by gender and by choosing “maintaining their certification” under the “certification status for age tables” filter (ABP, 2023m). The overall percentage appears as a comparison for “all subspecialties combined.” Data are as of June 14, 2023.

SOURCES: ABP, 2023k,l,m,q,r.

Analysis of Usage of Primary Care Clinicians for Pediatric Medical Subspecialty Care

As noted in Chapter 3, the committee received a data analysis14 that examined subspecialty care using the Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System (T-MSIS),15 a national administrative dataset of Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) beneficiaries. The T-MSIS analysis relied on primary specialty in the National Plan and Provider Enumeration System (NPPES) dataset, which may not fully capture physician subspecialties. T-MSIS data included enrollment, service usage, and provider information. The analysis used data from 2016 (the first available year of T-MSIS) through 2019. T-MSIS has known data quality challenges, which are analyzed and reported by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.16 The analysis included data from 44 states, DC, and Puerto Rico, and excluded Arkansas, California, Delaware, Indiana, Minnesota, and Pennsylvania.

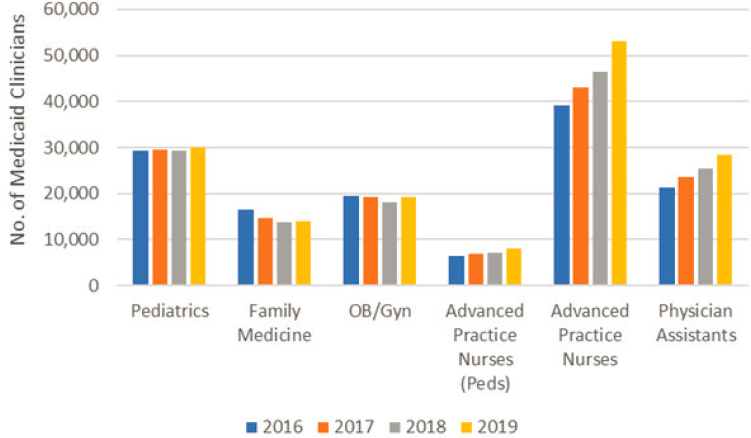

The T-MSIS analysis examined adult medical subspecialties that corresponded to pediatric counterparts as well as primary care specialties, including pediatrics, family medicine, internal medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, APRNs (pediatric), and physician assistants (medical). The analysis also included the specialty of psychiatry and subspecialty of child and adolescent psychiatry. In the primary care and advanced practice provider workforce that cares for children insured by Medicaid/CHIP, use of nurse practitioners and physician assistants increased significantly from 2016 to 2019 (see Table 4-7) and the number of advanced practice providers providing care to the pediatric Medicaid population also increased (see Figure 4-7). A limitation to these data is that because advanced practice providers working in subspecialty care may not have a subspecialty designation, counts of advanced practice providers likely represent growth across both primary and subspecialty care.

Nurses

Registered nurses (RNs) and APRNs are critical members of the pediatric health care team who assume numerous roles to meet a variety of care needs across diverse care settings (ICN, 2022; NASEM, 2021a). APRNs include nurse practitioners (NPs), clinical nurse specialists (CNSs), certified registered nurse anesthetists, and certified nurse midwives. RNs and APRNs can assume essential responsibilities related to: (1) caring for children with

___________________

14 All three data analyses submitted to this committee can be found at https://nap.edu/27207.

15 For more information on T-MSIS, see https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/data-systems/macbis/transformed-medicaid-statistical-information-system-t-msis/index.html (accessed October 11, 2023).

16 For more information, see https://www.medicaid.gov/dq-atlas/welcome (accessed May 4, 2023).

TABLE 4-7 Medicaid Outpatient Primary Care and Advanced Practice Provider Usage, T-MSIS 2016–2019

| Usage Rate per 1,000 Medicaid/CHIP Beneficiaries | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specialty | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

| Pediatrics | 463.1 | 444.9 | 427.9 | 493.60 |

| Family Medicine | 23.8 | 19.2 | 18.1 | 19.49 |

| Internal Medicine | 137.0 | 129.2 | 121.6 | 128.91 |

| Obstetrics-Gynecology | 11.9 | 7.5 | 7.1 | 7.67 |

| Advanced Practice Registered Nurses (Pediatrics) | 45.8 | 52.5 | 54.7 | 67.45 |

| Advanced Practice Registered Nurses | 88.9 | 107.1 | 117.2 | 147.80 |

| Physician Assistants | 50.6 | 57.8 | 63.2 | 75.46 |

| Adult Psychiatry | 8.5 | 8.3 | 8.2 | 8.87 |

| Child and Adolescent Psychiatry | 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 3.01 |

NOTES: Annual usage rates were computed as the number of pediatric Medicaid/Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) beneficiaries with one or more evaluation and management visits to a pediatric subspecialist per 1,000 Medicaid beneficiaries less than 19 years old. Clinician specialty was determined using the primary specialty in the National Plan and Provider Enumeration System dataset and may overrepresent the number of clinicians in primary care, such as for internal medicine physicians.

special health care needs; (2) leading teams to improve the care and reduce the costs of high-need, high-cost patients; (3) coordinating the care of children with special health care needs between the primary and subspecialty clinicians; (4) assessing problems to educate and plan with patients and families; and (5) evaluating outcomes (NASEM, 2021a,b). RNs can also lead transition initiatives between pediatric and adult care.

In general, nurses cover a broad continuum of care—from health promotion and disease prevention to curative care and care coordination to palliative care (IOM, 2011). In the context of subspecialty care, the use of RNs and APRNs in outpatient settings (e.g., primary care and ambulatory care) may help increase the availability of specialty care clinicians for the pediatric patients with the most critical or complex health care needs (Laurant et al., 2018; NASEM, 2021a,b; Perloff et al., 2016). With appropriate education and training, RNs and APRNs may provide the same care traditionally delivered by other clinicians such as “diagnostics, treatment, referral to other services, health promotion, management of chronic diseases, or management of acute problems needing same‐day consultations” (Laurant et al., 2018). In acute care settings, RNs and APRNs assume care management responsibilities supporting management of changing patient

NOTES: The number of Medicaid clinicians is a count of the number of clinicians by specialty with at least one evaluation and management claim for a beneficiary less than 19 years old in the calendar year. Clinician specialty was determined using the primary specialty in the NPPES dataset and may overrepresent the number of clinicians in primary care. Advanced practice provider numbers likely represent practice in both primary and subspecialty care. OB/Gyn = obstetrics-gynecology; T-MSIS = Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System.

conditions, preparing patients and families for discharge by providing education and self-management support, and facilitating transitions from acute to outpatient settings coordinating follow-up care and resources (Gonçalves et al., 2022; Semanco et al., 2022).

Nurse Practitioners

NPs are RNs who have additional education and clinical training in the care of a specific patient population that enables them to autonomously provide care to patients (NONPF, 2022). Since inception in the 1960s, the NP role and responsibilities evolved to meet patient health care needs and in response to evidence that they consistently provide high-quality care in diverse clinical settings (Aiken et al., 2021; Buerhaus, 2018; Gigli et al., 2021; NASEM, 2021a; Silver et al., 1968). While most NPs are trained in and practice in primary care settings, most NPs who provide pediatric care work in hospital and inpatient settings and one-third work in ambulatory

and clinical settings, providing pediatric subspecialty care (AANP, 2022; Gigli et al., 2023). NPs increase children’s access to care through their practice in settings that include: Federally Qualified Health Centers, retail clinics, home health, telehealth, schools and school-based health centers, nurse-managed health centers, ambulatory care clinics, as well as community and tertiary care hospitals (PNCB, 2022).

Although it is unclear how widely integrated NPs are in pediatric practices and hospitals, there is a demand for increased NP usage and expansion of the roles they play in care delivery (Freed et al., 2010a, 2011; Gigli et al., 2018; Merrit Hawkins Team, 2021). The NP workforce has more than doubled in the past decade and is expected to grow (Auerbach et al., 2018, 2020). NPs may be board certified in primary care pediatrics, acute care pediatrics, or both (AANP, 2023). There are more than 355,000 NPs in the United States, accounting for more than two-thirds of all APRN licenses (HRSA, 2019), but relatively few NPs choose to specialize in pediatrics (AANP, 2022; Freed et al., 2010a). Less than 4 percent of NPs specialize in pediatrics (2.4 percent primary care pediatric NPs, 0.6 percent acute care pediatric NPs) (AANP, 2022). A majority of NPs are family NPs (70.3 percent). Pediatric acute and primary care NPs report working in multiple subspecialties with pediatric patients, including adolescent care, cardiology, critical care, emergency care, gastroenterology, hematology/oncology, neonatology, and pulmonology (PNCB, 2022). A majority of the NP workforce who care for children are not certified specifically in pediatrics (e.g., family or psychiatric mental health NPs); the extent of their contribution to the delivery of pediatric subspecialty care is not well known (Gigli et al., 2023). There is no modeling for what types of services NPs provide, are needed for, or are best at providing in relation to pediatric subspecialty care. However, as noted earlier, the T-MSIS data analysis17 submitted to this committee found that both NPs in general and pediatric NPs are increasingly caring for children insured by Medicaid/CHIP (see Table 4-7).

Education, certification, and licensure

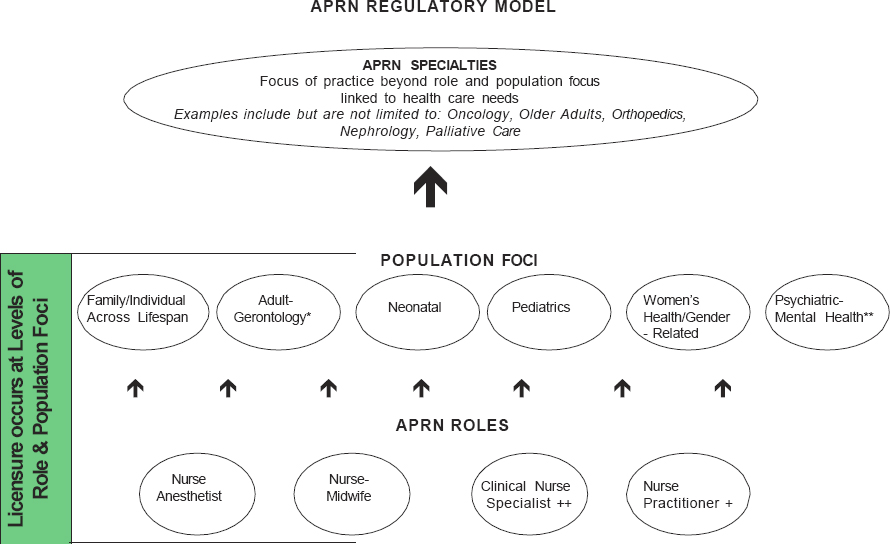

The Consensus Model for APRN Regulation, Licensure, Accreditation, Certification and Education (“The Consensus Model”) was developed in 2008 by a coalition of professional nursing organizations and established the framework for today’s APRN workforce (see Figure 4-8). The Consensus Model defines six patient population foci for APRN education, certification, licensure, and practice. Education programs meet national accreditation standards, and graduates must pass a national certification exam prior to licensure as an NP. An NP education is broad in exposure

___________________

17 All three data analyses submitted to this committee can be found at https://nap.edu/27207.

SOURCE: APRN Joint Dialogue Group, 2008. Reprinted with the permission of the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN).

to content across a population focus; as a result, specialty education (e.g., cardiology, oncology, critical care) predominantly occurs after completion of an NP program. There is no current mechanism or standardized process to evaluate or recognize an NP’s specialty practice expertise.

The Consensus Model outlines expectations that an NP’s practice aligns with their role in providing care (i.e., an NP working in a pediatric intensive care unit would be an acute care pediatric NP). According to a 2008 report on the Consensus Model:

The certified nurse practitioner (CNP) is prepared with the acute care CNP competencies and/or the primary care CNP competencies. At this point in time the acute care and primary care CNP delineation applies only to the pediatric and adult-gerontology CNP population foci. Scope of practice of the primary care or acute care CNP is not setting specific but is based on patient care needs. Programs may prepare individuals across both the primary care and acute care CNP competencies. If programs prepare graduates across both sets of roles, the graduate must be prepared with the consensus-based competencies for both roles and must successfully obtain certification in both the acute and the primary care CNP roles. CNP certification in the acute or primary care roles must match the educational preparation for CNPs in these roles.” (APRN, Joint Dialogue Group, 2008, p.10)

Over the ensuing decade since adoption of The Consensus Model, few states mandated such alignment (Gonzalez and Gigli, 2021), and no studies have examined the implications of alignment or misalignment between an NP’s education and certification and practice on patient outcomes (Hoyt et al., 2022).

Clinical Nurse Specialists

Like NPs, CNSs have additional education and clinical training and follow requirements for licensure and certification. In 2018, CNSs accounted for almost 20 percent of APRN licenses, or approximately 86,000 licensed CNSs (HRSA, 2019). According to a 2008 report on the Consensus Model, “the CNS has a unique APRN role to integrate care across the continuum and through three spheres of influence: patient, nurse, system” (APRN Joint Dialogue Group, 2008, p.8). CNSs may provide direct patient care, but also collaborate with other professionals to promote evidence-based care and processes, particularly for patients with complex care needs, provide support and education to other health care workers, and promote quality improvement initiatives (Lewandowski and Adamle, 2009; Saunders, 2015; Valdivia, 2022).

CNSs may receive population-based certifications in adult/gerontology, pediatrics, and neonatal care (NACNS, 2023). In a study of the 9,470 CNSs who were registered with a National Provider Identifier,18 most identified specialty areas of adult health (15.2 percent) and adult mental health (13.5 percent) (Reed et al., 2021). Only 6 percent indicated a specialty as oncology/pediatrics, pediatrics, perinatal, or neonatal and an additional 3 percent indicated a specialty in either child and adolescent or child and family psychiatric/mental health. The same study showed that the number of new CNSs specializing in pediatrics with a National Provider Identifier decreased from 2015 to 2019 (Reed et al., 2021).

School Nurses

An estimated 132,300 school nurses care for children in U.S. schools (Willgerodt et al., 2018). The 2021 National Academies report The Future of Nursing 2020-2030 describes the importance of school nurses:

School nurses are front-line health care providers, serving as a bridge between the health care and education systems. Hired by school districts, health departments, or hospitals, school nurses attend to the physical and mental health of students in school. As public health sentinels, they engage school communities, parents, and health care providers to promote wellness and improve health outcomes for children. School nurses are essential to expanding access to quality health care for students, especially in light of the increasing number of students with complex health and social needs. Access to school nurses helps increase health care equity for students. For many children living in or near poverty, the school nurse may be the only health care professional they regularly access. (NASEM, 2021a, p. 108)

Schools are increasingly being recognized not just as core educational institutions, but also as community-based assets that can be a central component of building healthy and vibrant communities (NASEM, 2017). Accordingly, schools and, by extension, school nurses are being incorporated into strategies for improving health care access, serving as hubs of health promotion and providers of population-based care (Maughan, 2018; NASEM, 2021a).

___________________

18 A National Provider Identifier (NPI) is “a unique identification number for covered health care providers, created to help send health information electronically more quickly and effectively. Covered health care providers, all health plans, and health care clearinghouses must use NPIs in their administrative and financial transactions” (CMS, 2022).

Physician Assistants

Physician Assistants (PAs) have the potential to play an important role in the care of children in the United States, and the National Commission on the Certification of Physician Assistants (NCCPA) offers a certification of added qualifications in pediatrics (NCCPA, 2023). However, the impact of PAs is limited by their relative scarcity in pediatric practice (Freed et al., 2010a). According to a survey of 3,373 PAs who were certified for the first time (in 2019), 23.1 percent work in primary care (i.e., family medicine, internal medicine, general pediatrics) (NCCPA, 2020). However, only 59 (1.8 percent) reported a principal clinical practice area in general pediatrics and an additional 53 (1.6 percent) worked in the pediatric subspecialties; none reported a principal clinical practice area in adolescent medicine. Few studies exist on the actual or conceptual use of PAs in pediatrics (Doan et al., 2012; Doan et al., 2015; Freed et al., 2011; Mathur et al., 2005). As noted earlier, the T-MSIS data analysis19 submitted to this committee found that usage rates of PAs for children insured by Medicaid/CHIP increased between 2016 and 2019 (see Table 4-7).

Primary Care Physicians

Some physicians who care for children may not necessarily complete a residency in general pediatrics, but instead are certified by another ABMS board. In fact, many ABMS boards apart from ABP offer subspecialty certificates related to the care of children and adolescents (see Table 4-8). Several of these subspecialties are included among the ABP non-standard pathways and combined training programs (see Chapter 1).

Adult-Trained Subspecialty Physicians Who Care for Children

Some children receive subspecialty care from adult-trained medical subspecialists (primarily internal medicine subspecialists). However, little is known about these practice patterns. In a study of children insured by Medicaid in Pennsylvania, Ray et al. (2016) found that adult subspecialists cared for 10 percent of children who received medical subspecialty care. The use of adult-trained subspecialists was higher (more than 18 percent) for children who lived farther away from a pediatric referral center. Similarly, one study of rheumatology referrals by primary care pediatricians in Minnesota, North Dakota, and South Dakota showed that 20 percent reported referring pediatric patients to adult rheumatologists, often because

___________________

19 All three data analyses submitted to this committee can be found at https://nap.edu/27207.

TABLE 4-8 ABMS Boards with Subspecialty Certificates in the Care of Infants, Children, and Adolescents

| ABMS Board | Subspecialty Certificates |

|---|---|

| American Board of Anesthesiology | Pediatric Anesthesiology |

| American Board of Dermatology | Pediatric Dermatology |

| American Board of Emergency Medicine | Pediatric Emergency Medicine |

| American Board of Family Medicine | Adolescent Medicine |

| American Board of Internal Medicine | Adolescent Medicine |

| American Board of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery | Complex Pediatric Otolaryngology |

| American Board of Pathology | Pathology-Pediatrics |

| American Board of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation | Pediatric Rehabilitation |

| American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology* | Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Neurodevelopmental Disabilities |

| American Board of Radiology | Pediatric Radiology |

| American Board of Surgery | Pediatric Surgery |

| American Board of Thoracic and Cardiac Surgery | Congenital Cardiac Surgery |

| American Board of Urology | Pediatric Urology |

NOTES: *This board offers specialty certificates in psychiatry, neurology, and neurology with special qualification in child neurology. ABMS = American Board of Medical Specialties.

SOURCE: ABMS, 2023.

of the shorter distance to the adult rheumatologist (as compared with a pediatric rheumatologist) (Correll et al., 2015). Ray et al. (2016) also found that other significant factors associated with a higher usage of adult-trained pediatric subspecialists were older age (i.e., 12 to 16 years old), minority race, lower neighborhood income, and managed care plan enrollment.

The T-MSIS data analysis20 submitted to this committee found that not insignificant numbers of adult subspecialists are providing subspecialty care for pediatric patients insured by Medicaid/CHIP. For example, as shown in Table 3-5 in Chapter 3, adult-trained allergy and immunology specialists see a higher number of outpatient Medicaid/CHIP pediatric patients compared with pediatric allergy and immunology subspecialists.

___________________

20 All three data analyses submitted to this committee can be found at https://nap.edu/27207.

Family Medicine Physicians

As part of their training, family physicians learn how to provide neonatal and routine newborn care, manage children who are acutely ill, and provide preventive health services to children (ACGME, 2022b). ACGME has program requirements for family medicine residency programs regarding the preparation of family medicine physicians in the care of children, but most program directors report challenges in meeting the required number of encounters (Krugman et al., 2023). Family physicians provide primary care, but typically do not address subspecialty care needs themselves (Bazemore et al., 2012; Makaroff et al., 2014; Phillips et al., 2006). However, as noted in Table 4-8, the American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM) does offer a certificate of added qualifications in adolescent medicine. The certification was first offered in 2001 and requires a 24-month fellowship in an ACGME-accredited fellowship in adolescent medicine (ABFM, 2023a); a search of the ABFM fellowship directory shows eight fellowship programs in the United States with a length of at least 24 months (ABFM, 2023b).

Previous studies have found that family medicine physicians provide 16 percent to 21 percent of physician visits by children (Jetty et al., 2021; Phillips et al., 2005). However, family physicians are decreasingly caring for children (Bazemore et al., 2012; Eden et al., 2020; Freed et al., 2004, 2010b; Wasserman et al., 2019), which could have significant repercussions on physician supply and access to care for children. For example, a recent cross-sectional survey showed a significant decline in the proportion of family medicine physicians caring for children under age five (from 92.5 percent to 87 percent) and ages 5 to 18 years (from 76.4 percent to 69.4 percent) between 2014 and 2018 (Eden et al., 2020). This trend was also seen with population-level data; using Vermont claims data, Wasserman et al. (2019) found that the percentage of children attending a family physician practice decreased from 2009 to 2016. In any given year, children were 5 percent less likely to see a family physician than a pediatrician compared with the year before (Wasserman et al., 2019). Most studies have found that children are more likely to see a family physician if they are female or have Medicaid, and are less likely to see a family physician if they live in an urban area. However, there have been mixed results about the more specific location (e.g., rural, suburban, area of the country) or age of children that are most likely to see family physicians (Cohen and Coco, 2010; Makaroff et al., 2014; Wasserman et al., 2019).

Jetty et al. (2021) found that scope of practice is often influenced by economic factors, geographic location, clinician age, and social factors, with pediatrician density also playing a role. In a qualitative study of family physicians, Russell et al. (2021) found that environmental, population, personal, and workplace factors all influence scope of practice, and

addressing these factors could help family physicians maintain a broader scope of practice.

Hospice and Palliative Care Physicians

As noted in Chapter 1, hospice and palliative care is one of the subspecialties that is co-sponsored by the ABP along with multiple other specialty boards (ABP, 2022). Certification is available to pediatricians who have primary certification by ABP (along with certain other specialties) and is administered by the American Board of Internal Medicine; certification requires one year of fellowship training in an ACGME-accredited hospice and palliative medicine program (AAHPM, 2023). According to the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, “pediatric palliative and hospice care focuses on enhancing quality of life for the child and family, preventing and minimizing suffering, optimizing function, and providing opportunities for personal and spiritual growth. This care can be provided concurrently with life-prolonging care, curative care, or as the main focus of care” (NHPCO, 2023). Challenges to the receipt of hospice and palliative care include poor communication, ineffective models of care, reimbursement barriers, misalignment of state and federal policies, and a lack of understanding of (including training) and/or referral for hospice and palliative care (Bogetz et al., 2022; Johnson et al., 2021; Mack et al., 2021; Perales-Hull and Klein, 2022). Pediatric nurse practitioners also provide palliative care to children, and report challenges in their preparation for this role (Brock, 2021).

MENTAL HEALTH, BEHAVIORAL HEALTH, AND SOCIAL CARE PROFESSIONALS

While many clinicians are involved in addressing psychosocial needs of their patients, and a variety of professionals focus on psychosocial care, this section focuses on the care providers who focus their attention primarily on mental health, behavioral health, and psychosocial care needs—namely, psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers. The committee recognizes that many APRNs and PAs focus on child and adolescent mental health, but they are not discussed in this section.

Child and Adolescent Psychiatrists

A child and adolescent psychiatrist (CAP) “specializes in the diagnosis and treatment of disorders of thinking, feeling, and/or behavior affecting children, adolescents, and their families” (AACAP, 2023a). CAPs work with patients and families to develop care plans that may include individual,

group or family psychotherapy; medication; and/or consultation with other physicians or professionals from schools, juvenile courts, social agencies, or other community organizations. CAPs also act as advocates for the best interests of children and adolescents and perform consultations in a variety of settings (e.g., schools, juvenile courts, social agencies).

Estimations of the number of actively practicing CAPs are challenging because there is limited information about the proportion of time the average psychiatrist spends caring for children and adolescents. However, a 2018 analysis estimated that there were 9,956 actively practicing CAPs (approximately 15 CAPs per 100,000 children under 18 years) (Beck et al., 2018). CAPs were located in 28 percent of counties across the country, primarily in the northeastern United States as well as some counties on the West Coast.

Education and Training

CAP training includes 4 years of medical school; at least 3 years of residency training in medicine, neurology, and general psychiatry with adults; and 2 years of additional residency training in child and adolescent psychiatry (AACAP, 2023a). CAP residencies prioritize attention to “disorders that appear in childhood, such as pervasive developmental disorder, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), learning disabilities, mental retardation, mood disorders, depressive and anxiety disorders, drug dependency and delinquency (conduct disorder)” (AACAP, 2023a). After completion of the CAP residency, CAPs are certified in general psychiatry by the American Board on Psychiatry and Neurology and may pursue subspecialty certification in child and adolescent psychiatry. In 2023, NRMP reported that 505 positions were offered in CAP in 127 programs, with an 82.4 percent match rate (NRMP, 2023b). Sixty-four percent of applicants were graduates of M.D. programs in the United States, 16 percent were graduates of osteopathic medical schools, and 20 percent were international medical graduates. The number of CAP positions and programs has increased since 2019; in 2019, 350 positions were offered in 108 programs.

As noted in Chapter 1, ABP has an agreement with the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology wherein an applicant can complete requirements for certification in pediatrics, psychiatry, and CAP (“triple certification”) at one of 11 combined training programs (ABP, 2023s). The combined program is 5 years in length and must include 24 months of training in pediatrics, 18 months of training in general psychiatry, and 18 months of training in CAP. Apart from ABP, child and adolescent psychiatrists may be trained through a variety of mechanisms such as traditional training programs, integrated training programs, and the Post Pediatric Portal Program (AACAP, 2023b).

Psychologists

Roberts and Steele (2017) define pediatric psychology as a multidisciplinary field that includes “both research and clinical practice that address a range of issues related to physical and psychosocial development, health, and illness among children, adolescents, and their families.” (pg. 3). Psychologists possess the expertise and clinical proficiency to assist individuals in acquiring better coping strategies to manage mental health issues and various challenges in life through therapy (APA, 2023). Psychologists can be integrated in pediatric health care settings and systems (e.g., hospitals, pediatric subspecialty clinics, primary care) to help meet the needs of children and families facing chronic illnesses or disabilities (White and Belachew, 2022). (See Chapter 7 for more information on behavioral health integration.) Some pediatric health care subspecialty clinics have psychologists that are trained to care for children with comorbid medical and psychological conditions embedded in the practice, so that they can work collaboratively with the pediatric subspecialists (Apple and Clemente, 2022). Areas of expertise for pediatric psychologists include: “psychosocial, developmental and contextual factors contributing to the etiology, course and outcome of pediatric medical conditions; assessment and treatment of behavioral and emotional concomitants of illness, injury, and developmental disorders; prevention of illness and injury; promotion of health and health-related behaviors; education, training, and mentoring of psychologists and providers of medical care; improvement of health care delivery systems and advocacy for public policy that serves the needs of children, adolescents, and their families” (SPP, 2023). Psychologists can also receive specialty training in clinical child and adolescent psychology (Lin and Stamm, 2020).

Education and Training

The training pathway for pediatric psychologists typically involves completion of a Ph.D. or Psy.D. graduate program (generally 4–6 years of full-time study), including clinical practicum training. Some graduate programs offer specialized tracks in pediatric psychology. Prior to obtaining a doctoral degree, candidates must complete a one-year supervised internship. In most states, an additional year of supervised practice is required for licensure. Accredited pediatric psychology internships offer clinical exposure and research opportunities, leading to clinical competence. There are postdoctoral fellowships in pediatric psychology that typically last 1 to 2 years and provide additional training in pediatric clinical care and research. Many fellowships are based in hospitals and offer clinical experience with children facing acute and chronic disorders. Finally, psychologists must pass

a national examination and additional state-specific examinations to obtain licensure (APA, 2023; Boat et al., 2016; Palermo et al., 2014).

Numbers of Pediatric Psychologists

Similar to CAPs, it is challenging to determine the exact number of practicing pediatric psychologists, partly because state boards grant licensure to psychologists in a general manner for both children and adults. Using data from the 2015 American Psychological Association Survey of Psychology Health Service Providers, the National Plan and Provider Enumeration System/National Provider Identifier Registry, and the American Board of Professional Psychology Board Certifications, Lin and Stamm (2020) found that nearly 6 percent of licensed doctoral-level psychologists self-reported a clinical child and adolescent specialty (4,012 out of 69,655) and approximately 6 percent of board-certified psychologists were certified in clinical child and adolescent psychology (268 out of 4,300) in the United States. However, the authors suggest that the number of psychologists that care for children and adolescents is likely higher than these data show, as the APA survey data show “23 percent of psychologists provide services to children frequently or very frequently and 34 percent provide services to adolescents frequently or very frequently” (Lin and Stamm, 2020). The data show that the distribution of clinical child and adolescent psychologists is uneven across the country, with the majority located in the Northeast and along the West Coast (Lin and Stamm, 2020).

Social Workers

The 2021 National Academies study Implementing High-Quality Primary Care identified social workers as an important part of the extended primary care team (NASEM, 2021b). For children, social workers can play a critical role on health care teams and can contribute to care coordination, the integration of behavioral health and primary care, and the provision of psychosocial support for inpatient and outpatient pediatric patients and their families (Children’s National, 2023; Hospital for Special Surgery, 2023; Johns Hopkins Medicine, 2023; Jones et al., 2018; Ross et al., 2018). The National Association of Social Workers offers a Specialty Practice Section for supporting the development of “children, adolescents, and young adults” (NASW, 2023a). The section has a particular focus on physical, emotional, and behavior disorders as well as supporting transitions through young adulthood. Furthermore, social workers play a key role in children’s well-being through their involvement in child welfare (e.g., child protective services, case management) (NASW, 2023b). In general, the inclusion of social workers in primary care settings has been associated with improved health outcomes (Cornell et al., 2020; Rehner et al., 2017).

OTHER RELATED HEALTH PROFESSIONALS

Many other professionals specialize in the care of children, such as dentists, pharmacists, podiatrists, and a broad array of therapists. While these members of the overall pediatric workforce are not the main focus of this study, many are active at the front lines of care and play an important role in referral and access to pediatric subspecialists. The following section highlight some of these professionals.

Care Coordinators

A variety of individuals with various titles and overlapping responsibilities help patients to coordinate their care needs across providers to and navigate the health care system overall. Some of the most common titles include care coordinators, care managers, case managers, and patient navigators. These roles are often filled by nurses or social workers. In these roles, the workers help to overcome barriers to care at the level of the patient, their socioeconomic environment, and the larger health care system. Activities may include patient education; assistance with insurance, transportation, or legal issues; referral to community resources; and encouragement to adhere to follow-up care (Joo and Huber, 2017; Kelly et al., 2015; Paskett et al., 2011; Woodward and Rice, 2015). While there are discrepancies in the definitions, scopes of practice, or qualifications for these individuals, there is evidence that care coordination contributes to improved outcomes in health care broadly (Berry et al., 2013; Gorin et al., 2017; NEJM Catalyst, 2018; Ruggiero et al., 2019).

Community Health Workers

Community health workers (CHWs) work within their communities to promote health and wellness; they are also known as outreach workers, community health advocates, community health representatives, and patient navigators (Rosenthal et al., 1998, 2010). There are more than 60,000 paid CHWs in the United States (BLS, 2023), as well as many volunteers (HRSA, 2023; Rosenthal et al., 2010). There is no standardized education or training, or scope of practice, for CHWs (Catalani et al., 2009). CHWs provide a wide range of services, including health education and coaching, medication adherence, care coordination, social support, outreach and engagement, health assessment and screenings, patient navigation, case management, program implementation, and referral management for medical and social services (BLS, 2023; HRSA, 2023; NASEM, 2020). CHWs also play an important role in addressing health disparities and improving health outcomes, particularly for underserved and marginalized populations

(Cosgrove et al., 2014; HRSA, 2023; Lewin et al., 2010; Vasan et al., 2020). Research has shown that CHWs increase disease knowledge, self-management, and health outcomes for children and youth with chronic diseases (Coutinho et al., 2020; Fox et al., 2007; Lewin et al., 2010; Randolph et al., 2021; Viswanathan et al., 2010). CHWs work collaboratively with clinicians, social workers, and other professionals to improve the health and well-being of the communities they serve, and may work in a variety of settings, such as community clinics, Federally Qualified Health Centers, hospitals, schools, and public health agencies.

KEY FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS

Key Findings

Finding #4-1: The current model of education and training for pediatric medical subspecialists focuses on the creation of academic pediatric specialists who demonstrate competency in core aspects of academic careers: clinical care, research, and education.

Finding #4-2: Limited resources and time may prevent training programs from adapting curricula quickly.

Finding #4-3: Pediatrics residents and fellows report feeling unprepared in key areas such as cultural competence and mental and behavioral health.

Finding #4-4: The ABP/ACGME requires all pediatric medical subspecialty fellowships to engage in scholarly activity (see also Chapter 5).

Finding #4-5: Fellowship position fill rates and numbers of first-year fellows show significant variation across the pediatric medical subspecialties.

Finding #4-6: A smaller percentage of female medical subspecialists report working full time or working 50 or more hours per week (as compared with male medical subspecialists).

Finding #4-7: Nearly half of actively practicing pediatric medical subspecialists do not participate in any research activities.

Finding #4-8: Most subspecialists practice in urban settings in a medical school or parent university, a non-government hospital or clinic, or a pediatric or multispecialty group practice.

Finding #4-9: Pediatric subspecialists are increasingly female and from URiM backgrounds. However, the pediatric workforce does not reflect the growing diversity of the U.S. population, particularly the pediatric population.

Finding #4-10: The health care usage of pediatricians, advanced practice nurses, and physician assistants providing outpatient care to the pediatric population insured by Medicaid increased from 2016 through 2019. However, there are not enough standard training programs or certifications for pediatric subspecialty NPs and PAs.

Finding #4-11: Adult-trained subspecialists provide a significant amount of care to children, but evidence about their numbers and patterns of care is scarce.

Finding #4-12: Family medicine physicians are decreasingly caring for children.

Finding #4-13: CAPs, child psychologists, and social workers provide crucial support for the mental health, behavioral health, and psychosocial care needs of children.

Finding #4-14: There is a paucity of data on the overall pediatric health care workforce, including both subspecialists and non-subspecialists.

Conclusions

Conclusion #4-1: The current model of education and training has not evolved substantially in response to the changing context of society and medicine, including the changing health needs of pediatric patients, changing practice patterns, and the changing needs of trainees.

Conclusion #4-2: Pediatric education and training needs to be more responsive to the changing needs of infants, children, and adolescents.