The Future Pediatric Subspecialty Physician Workforce: Meeting the Needs of Infants, Children, and Adolescents (2023)

Chapter: 6 Trends in the Pediatric PhysicianScientist Workforce

6

Trends in the Pediatric Physician–Scientist Workforce

Pediatric subspecialty physicians play a critical role in pursuing the research that leads to advances in child health. The robustness and endurance of the pediatric physician–scientist workforce pathway can have long-lasting effects on child and adolescent health through research to prevent, diagnose, and treat diseases that occur specifically in children or begin in childhood and affect the life course. As a result, advances in pediatric research have improved the lives of both children and adults. This chapter summarizes the pediatric research landscape in general, including examples of previous successes and unique challenges inherent to pediatric research. The chapter then delves into factors and barriers that affect the pediatric physician–scientist pathway and impact the ability of the physician subspecialty workforce to pursue a robust research portfolio that advances the care of all children and youth. There is limited available information specific to pediatric subspecialists, so much of this chapter is on the overall pediatric research workforce while considering the implications for research by physician–scientists in the pediatric medical subspecialties specifically. The challenges faced by the pediatric physician–scientist workforce are further compounded given the smaller numbers of pediatric subspecialists. Additionally, while other clinician scientists1 and non-clinician scientists (i.e., Ph.D. scientists who study pediatric subspecialty conditions and treatments) are discussed as relevant, the focus of this chapter is on the pediatric physician–scientist workforce.

___________________

1 For more information on the National Pediatric Nurse Scientists Collaborative, see https://npnsc.org/ (accessed May 3, 2023).

THE IMPORTANCE OF PEDIATRIC RESEARCH

In 1979, James B. Wyngaarden described “The Clinical Investigator as an Endangered Species” in his presidential address to the Association of American Physicians (Wyngaarden, 1979). Since then, discussions have continued about the plight of the physician–scientist, including pediatric physician–scientists specifically (Alvira et al., 2018; Daye et al., 2015; Milewicz et al., 2015; Rubenstein and Kreindler, 2014; Salata et al., 2018; Schafer, 2010; Zemlo et al., 2000). The scope of the pediatric research enterprise is transdisciplinary and has broadened to include the full spectrum of basic science, translational, community-based, population health, health services, health equity, and child health policy research (AAMC, 2023a; COPR, 2014; Williams et al., 2022). Furthermore, the development, recruitment, and retention of pediatric physician–scientists is critical to accelerate advances in wide-ranging fields such as molecular biology, genetics, genomics, precision medicine, health care delivery, health services research, and injury prevention (Alvira et al., 2018).

Pediatric Research Successes

Improving children’s health is essential to developing a productive and healthy population (NRC and IOM, 2004), and research is the foundation of evidence-based innovation in pediatric care. Recent developments in research and clinical care include the increasing application of genome sequencing to diagnosis, clinical monitoring, and treatment; progress in developing cell therapy for cancers that are resistant to treatment; advances in developing gene therapy for a growing number of single gene disorders; targeted research on surfactant therapies for pediatric and neonatal acute respiratory distress syndrome; immunotherapeutic modalities for the treatment of pediatric malignancies; and a clearer understanding of the relationship between the microbiome and specific diseases (Baruteau et al., 2017; Bick et al., 2019; De Luca et al., 2021; Gilbert et al., 2018; Holstein and Lunning, 2020; Hutzen et al., 2019; Janssens et al., 2018). Some examples of notable pediatric scientific achievements are listed in Box 6-1.

Success stories serve as testimony to the transformative impact of scientific discovery on clinical care, but such discoveries require ongoing efforts and partnerships among medical schools, hospitals, payers, advocates, clinicians, and researchers to address rising challenges and to optimize access of therapeutics to children as early as possible. Boxes 6-2 and 6-3 highlight two specific case studies of pediatric research success: spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) and the Children’s Oncology Group (COG). Challenges and controversy have unfolded as health systems navigate this era of precision health in pediatric disease, including access, handling, and delivery of

these drugs, particularly in the context of their high cost (zolgensma, used to treat SMA, costs $2.1 million per dose). These precision health opportunities also have motivated expansion of the newborn screening program and development of scalable assays to accelerate timely diagnosis of these now-curable conditions.

There has also been advancement in research, evaluation, and measurement infrastructure for child health services research, such as the increased representation of children in the National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network (PCORnet) (Forrest et al., 2021) and the establishment of the National Cancer Institute Childhood Cancer Data Initiative (NCI, 2023a). Other examples of success can be seen in the substantial advancements in the care of prematurely born infants. Use of intrapulmonary surfactant and improvements in ventilation strategies, external environment

management, and neuromonitoring devices have improved viability (defined as the gestational age at which there is a 50 percent chance of survival with or without medical care) from 25 to 26 weeks’ gestation in the mid-1990s to 23–24 weeks gestation by the mid-2000s (Glass et al., 2015). Innovative research also has been applied to directly improving patient outcomes through the development of pediatric learning health systems (Forrest et al., 2021; Varnell et al., 2023) and uncovered insights related to implicit bias and racism on child and adolescent health (Goyal et al., 2020, 2015; Johnson et al., 2017a; Priest et al., 2013; Puumala et al., 2016; Trent et al., 2019). In addition to improved pediatric patient outcomes, pediatric research has far-reaching impacts on both children and adults’ life course health related to health equity, social and structural determinants of health, and other pressing issues that can improve health across the lifespan (Braveman et al., 2009; Cheng et al., 2022; Halfon et al., 2022; Woodward et al., 2022). (See Chapter 2 for more information on additional emerging health needs for pediatric patients that could be supported by pediatric research.)

UNIQUE CHALLENGES OF PEDIATRIC RESEARCH

Pediatric studies bring specific challenges, including ethical considerations, logistical and technical factors in administering interventions, smaller population size (especially for subspecialty care), developmental considerations in studying children across ages, reluctance to include pregnant women and their fetuses in clinical intervention research, and financial disincentives related to the limited commercial market potential for pediatric drugs compared with adult drugs (Blehar et al., 2013; Burckart, 2020; Caldwell et al., 2004; Kern, 2009; Rees et al., 2021; Shakhnovich et al., 2019; Steinbrook, 2002). As a result, despite the potential for lifelong benefit, fewer studies are conducted in children, even for diseases and conditions that are common in pediatrics, and children tend to be underrepresented in randomized clinical trials for diseases that affect both adults and children (Groff et al., 2020; Hwang et al., 2020; Thomson et al., 2010). Similarly, fewer clinical trials are performed in children compared with other patient populations (Bourgeois et al., 2014; Viergever and Rademaker, 2014), and “while as much as 65 percent of funding for studies in adult populations is provided by the pharmaceutical industry, nearly 60 percent of pediatric clinical trials are sponsored primarily by government and nonprofit organizations” (Rees et al., 2021, p.1237), showcasing the lack of financial incentives for robust industry participation in pediatric research.

Historical Limitations of Pediatric Research Compared with Adult Research

Historically there has been a mismatch between the number of pediatric randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and pediatric disease burden (Groff et al., 2020). Older studies have noted this paucity of pediatric RCTs in published literature (Cohen et al., 2007, 2010; Thomson et al., 2010). Bourgeois et al. (2012) reviewed the clinical trial landscape for conditions known to have pediatric involvement and found that nearly 60 percent of the disease burden was attributable to children, but only 12 percent of trials were pediatric. The authors concluded that the significant disparity between pediatric burden of disease and the level of clinical trial research devoted to pediatric populations may be due in part to having to rely on non-industry funding sources.

The evidence base for treatment and health research and development in children also lags behind that for adults (Viergever and Rademaker, 2014). A major contributor is the lack of pediatric natural history and clinical registry data due to the logistic, ethical, and legal challenges of performing clinical investigations in children (Brussee et al., 2016; Goulooze et al., 2020). Current data collection methods are based on experience with adult populations and do not sufficiently capture the effects of family, environment, and biological factors on children’s health and development. Specific aspects of pediatric RCTs that can undermine recruitment, retention, and trial success include ethical considerations around parental consent and child assent, scientific challenges in the paucity of well-validated clinical endpoints or biomarkers in children, and logistical issues such as the time and financial resources needed for participation. Overall consent rates in pediatric RCTs have improved, but are still not optimal (Groff et al., 2020; Lonhart et al., 2020), especially among minoritized groups.

A review of pediatric studies in ClinicalTrials.gov2 from 2008 to 2019 found a total of 36,136 clinical trials and 16,692 observational studies, with the number of pediatric clinical trials nearly doubling over this period (from 7,000 to almost 12,000), and with an overall decrease in drug trials, but an increase in behavioral trials (Zhong et al., 2021). Pediatric trials were mostly small scale, single site, and usually not funded by industry or the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

___________________

2 ClinicalTrials.gov is a database of clinical studies around the world and is provided by the U.S. National Library of Medicine.

Regulatory Landscape and Historical Efforts to Improve Pediatric Drug Development

Largely due to the challenges in pediatric research described previously, far more drugs have been approved for clinical use in adults than for pediatric populations, which leads to a significant proportion of drugs in children being an “off label” use for various medical conditions (Sachs et al., 2012). As a result, most drugs used to treat children are used without an adequate understanding of appropriate pharmacokinetics, dose, safety, or efficacy (NICHD, 2022a). Among other legislative attempts, two laws have aimed to address the study of drugs in pediatric populations—the Pediatric Research Equity Act (PREA)3 and the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act (BPCA), which provide requirements and incentives with the aim to expand the study of drugs in children (IOM, 2012).4 Specifically, PREA authorized the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) “to require pediatric studies in certain drugs and biological products. Studies must use appropriate formulations for each age group. The goal of the studies is to obtain pediatric labeling for the product” (FDA, 2019b). BPCA’s aim is to (1) “encourage the pharmaceutical industry to perform pediatric studies to improve labeling for patented drug products used in children by granting an additional 6 months of patent exclusivity,” and (2) “authorize NIH…to prioritize needs in various therapeutic areas and sponsor clinical trials of off-patent drug products that need further study in children, as well as training and other research that addresses knowledge gaps in pediatric therapeutics” (NICHD, 2022c). The two acts together contributed to the safe and effective use of more than 400 drugs within the first 5 years of implementation (Burckart, 2020), and today there are more than 1,050 small-molecule and biologic products with pediatric labeling from the results of these acts.5 However, Benning et al. (2021) found that pediatric label changes were not associated with subsequent changes in pediatric drug use, and although some drugs had increased pediatric use after gaining new pediatric indications, the pattern was not consistent.

Recent policy efforts to improve pediatric drug development also include the Research to Accelerate Cures and Equity for Children (RACE) Act, which requires evaluation of new drugs and biologics “substantially relevant to growth or progression” of pediatric cancer (Caruso, 2020), and the establishment of the Rare Pediatric Disease Priority Voucher Program,

___________________

3 Pediatric Research Equity Act of 2003, Public Law 108-155, 108th Congress.

4 Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act of 2002, Public Law 107-109, 107th Congress.

5 Current as of June 27, 2023. See https://www.fda.gov/science-research/pediatrics/pediatric-labeling-changes (accessed June 27, 2023) to see access the Pediatric Labeling Changes Spreadsheet.

which awards companies with priority review for drugs targeting a list of rare diseases (Coppes et al., 2022; Hwang et al., 2019).

Diversity and Inclusion in Pediatric Research Populations

Representative and inclusive clinical trials include people’s heterogeneous lived experiences and living conditions, as well as demographic characteristics such as race and ethnicity, age, sex, and sexual orientation/gender identification (NIH, 2022a). The efficacy of treatments is best assessed when a diverse population is included in clinical trials (Masters et al., 2022). As with adult research, pediatric clinical trials have not always been appropriately inclusive of populations experiencing health disparities (Aristizabal et al., 2015; Faulk et al., 2020; Lund et al., 2009; Walsh and Ross, 2003; Winestone et al., 2019). Rees et al. (2022) found that most racial and ethnic groups were underrepresented in the trials conducted in the United States.

In recent years, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and NIH have made explicit efforts to increase inclusion of pregnant and lactating people, children, and people with intellectual disabilities in their research (Spong and Bianchi, 2018); however, there is still work to be done. For example, Chen et al. (2022) found that non-English-speaking communities were underrepresented in pediatric health research from 2012 to 2021, and only one in 10 pediatric research studies included patients with limited English proficiency. In addition, Watson et al. (2022) found that children in rural settings are underrepresented in clinical trials, potentially contributing to rural health disparities. As the pediatric population of the United States continues to become more diverse, including diverse populations in pediatric clinical trials is critical. Furthermore, Popkin et al. (2022) emphasized that meaningful inclusion in clinical research begins with training diverse medical and scientific workforces and enhancing the diversity of research and clinical teams. See later section on increasing the diversity of pediatric researchers, Chapter 4 for the current demographics of pediatric subspecialists, and Chapter 5 for influences on career choice for individuals who are underrepresented in medicine.

THE PEDIATRIC PHYSICIAN–SCIENTIST WORKFORCE

No single term defines a pediatric researcher, as individuals with a variety of professional backgrounds can engage in investigational activities. Physician–scientists possess a unique combination of clinical and research expertise based on their education and training that enables them to identify knowledge gaps in clinical care and research questions, gain

a comprehensive understanding of critical aspects of medical physiology through clinical epidemiology and disease-specific features, act as a bridge between basic science researchers and clinicians, and develop research strategies aimed at uncovering breakthroughs that can enhance clinical care (Singh et al., 2018; Williams et al., 2022; Yap, 2012). For the purposes of this report, the committee focused on the pediatric physician–scientists, namely those with M.D., D.O.,6 M.D./Ph.D., or M.D./MPH degrees who perform biomedical, behavioral science, health services research, or public health research of any type as their primary professional activity. This definition includes physician–scientists who are conducting “basic research” (fundamental investigations not specific to disease or patient population), “disease-oriented research” (investigations into the causes or treatments of diseases, with no patient involvement), or “patient-oriented research” (clinically oriented studies with direct patient contact) (Zemlo et al., 2000).

The Physician–Scientist Pathway

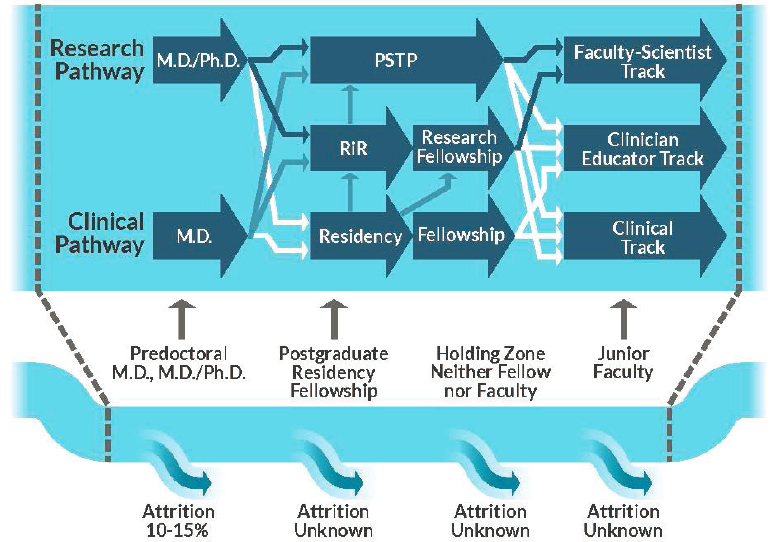

The decision to pursue a career as a physician–scientist can be made at many points in an individual’s training. The physician–scientist pathway has been described as “long and leaky” (Milewicz et al., 2015). Figure 6-1 highlights the physician–scientist workforce pathway and points of attrition, with best known estimates of losses, as well as the entry points for recruitment, though data are lacking across the continuum. There are various ways in which individuals may experience research career attrition, and each stage can have a cumulative effect. Researchers may choose not to return to research, pursue full-time clinical practice outside of academia, become assistant professors within academia but predominantly focus on patient care, obtain tenure but allocate little time to research, or substantially reduce the amount of research effort at varying points in their academic careers (Milewicz et al., 2015; NIH, 2014). Unfortunately, data on attrition rates specific to pediatric subspecialties are unknown. Across all disciplines, the numbers of physician–scientists have diminished, and the length of their productive scientific careers has decreased, with the average age of first independent funding at 46 years old (Daniels, 2015; Kerschner et al., 2018).

There are two major ways that pediatrician physician–scientists begin their career: directly following completion of an M.D. or D.O. program, and

___________________

6 The research literature primarily focuses on those with M.D. or M.D./Ph.D. and less on physician–scientists with D.O. degrees. However, there are increasing numbers of D.O. degrees among physician-scientists.

NOTES: Labeled block arrows represent training opportunities. Arrows indicate options for transitions between training programs, with solid navy arrows denoting the standard research-based physician–scientist training pathway, solid blue arrows indicating on-ramps, and solid white arrows showing points of physician–scientist loss, where trainees opt not to pursue research-based careers. PSTP: physician–scientist training program; RiR: research in residency.

SOURCES: Adapted from Williams et al., 2018; Milewicz et al., 2015. Used with permission of JCI Insight, permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

through M.D.-Ph.D. programs. Additionally, international medical graduates may be a resource for increasing the number of physician–scientists.

Following M.D./D.O. Programs

As mentioned in Chapters 4 and 5, the conventional pathway for a pediatric subspecialist involves completing a pediatric residency and then pursuing a subspecialty fellowship. During this fellowship, the trainee selects an academic focus that will serve as the foundation of their career development. Scholarly activity is a required component of most residency training programs as well as pediatric fellowship programs. In most pediatric fellowship programs, the initial year of training is largely clinical; trainees rarely have an opportunity to experience a research setting until their

second year of training. As a result, by the time they become fully integrated into a laboratory or clinical research program, establish a research focus, and begin to acquire the necessary tools to test hypotheses, they are often well into their second or third year of training. This can make it challenging to complete an independent research project—typically defined as a first author, peer-reviewed publication—by the end of a 3-year fellowship, let alone develop the skills and focus to be successful as a physician–scientist (Rubenstein and Kreindler, 2014).

Evidence shows that formal, structured research tracks have led to greater trainee research engagement (Ercan-Fang et al., 2017). As noted in Chapter 5, the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) has developed several specialized physician–scientist training structures to speed up the time to become a pediatric physician–scientist, which reflect the frequent calls to reduce training time for physician–scientists (Blish, 2018; Milewicz et al., 2015). These integrated clinical and research pathways are also used by the American Board of Internal Medicine and the American Board of Family Medicine (Doubeni et al., 2017; Todd et al., 2013). There are also several institutional physician–scientist training initiatives (e.g., “umbrella” programs) that include seminars and research forums, along with providing research funding (Permar et al., 2020; Williams et al., 2022).

Following fellowship training, the most common pathway to an independent, academic career for pediatric subspecialty fellows is the transition from fellowship to junior faculty by way of a mentored physician–scientist award, usually in the NIH K series. The competition for these awards is high (see section on NIH funding later in this chapter), though the success rates between “M.D.-only” researchers and Ph.D.s or M.D.-Ph.D.s is comparable (Ley and Hamilton, 2008; NIH, 2014) (see section on M.D.-Ph.D.s).

International Medical Graduates

International medical graduates are individuals who received their primary medical degree from a medical school outside the United States and Canada. There have been proposals to better integrate international medical graduates into the research workforce to address the physician–scientist shortages (Muraro, 2002; Vidyasagar, 2007). However, while international medical graduates represent nearly one-fourth of the pediatric workforce, less than 1 percent designate research as their major professional activity (Duvivier et al., 2020).

M.D.-Ph.D. programs

M.D.-Ph.D. programs combine medical and graduate school within an integrated curriculum in order to train physicians for a career that combines clinical perspectives with research (Akabas et al., 2018). The

number of students entering M.D.‐Ph.D. programs has been slowly rising, and most graduates become academic physician–scientists (Garrison and Ley, 2022). A 2010 study by Brass and colleagues showed that attrition rates from M.D.-Ph.D. programs averaged 10 percent, and suggested the low rate might be because trainees typically receive tuition waivers for both medical school and graduate school plus a stipend. At that time, most of those who withdrew completed medical school or graduate school; approximately 80 percent of M.D.-Ph.D. program graduates worked in academia, industry, or research institutes (Brass et al., 2010). Over the past 50 years, the M.D.-Ph.D. training time in the United States has steadily increased, increasing from just over 6 years before 1975 to over 8 years in 2014, with no evidence that spending more time as an M.D.-Ph.D. student resulted in a greater research effort years later (Brass and Akabas, 2019).

M.D.-Ph.D. students represent approximately 3 percent of all medical students graduating each year (Akabas et al., 2018). In 2022, M.D.-Ph.D. programs matriculated 709 students and had an enrollment totaling 6,005 trainees in 155 medical schools across all disciplines (AAMC, 2022a). Roughly half of the programs are supported by NIH through a T327 mechanism from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, which provides financial support and consistency in training activities (Williams et al., 2022). According to survey data from 2015, approximately 13 percent of M.D.-Ph.D. program graduates chose residency training in pediatrics (Akabas et al., 2018). Among those that chose to pursue a pediatrics residency, approximately 82 percent reported a subspecialty fellowship choice, with the largest percentages in hematology/oncology (21 percent), medical genetics (10 percent), endocrinology (7 percent), and infectious disease (7 percent) (Akabas et al., 2018). Table 6-1 includes the most recent data of M.D.-Ph.D. dual-degree program graduates from U.S. M.D.-granting medical schools in pediatric subspecialties.

Historically, M.D.-Ph.D. graduates have tended to cluster in certain fields, including pediatrics (Andriole et al., 2008; Paik et al., 2009). However, more recent data have indicated a trend away from the historical trends of internal medicine, pediatrics, neurology, and pathology (Akabas et al., 2018; Brass et al., 2010). This trend of decreasing M.D.-Ph.D. graduates in pediatrics may have implications for the overall pediatric research workforce.

___________________

7 An NIH T32 award is an Institutional Training Grant that is made to institutions to support groups of pre- and/or postdoctoral fellows, including trainees in basic, clinical, and behavioral research. Purpose: Ensures that a diverse and highly trained workforce is available to assume leadership roles in biomedical, behavioral, and clinical research. Issued to eligible institutions to support research training for groups of pre- and/or postdoctoral fellows. The number of positions or “slots” varies with each award (NICHD, 2023a).

TABLE 6-1 M.D.-Ph.D. Residents by Subspecialty, 2019–2021

| Subspecialty | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescent Medicine | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Child Abuse Pediatrics | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine | 15 | 18 | 15 |

| Pediatric Cardiology | 15 | 12 | 7 |

| Pediatric Critical Care Medicine | 8 | 6 | 9 |

| Pediatric Emergency Medicine | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| Pediatric Endocrinology | 5 | 5 | 6 |

| Pediatric Gastroenterology | 5 | 5 | 8 |

| Pediatric Hematology/Oncology | 36 | 27 | 25 |

| Pediatric Infectious Diseases | 21 | 18 | 17 |

| Pediatric Nephrology | 5 | 5 | 6 |

| Pediatric Pulmonology | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Pediatric Rheumatology | 10 | 10 | 9 |

NOTE: *Hospital medicine excluded as there were no M.D.-Ph.D. graduates as active residents from 2019 through 2021.

SOURCE: AAMC, 2022b.

Data Limitations and Effect on Pediatric Physician–Scientist Workforce Projections

It is difficult to characterize the pediatric physician–scientist workforce overall (including numbers) due to data limitations and little to no coordination between the funders and other parties involved in the pediatric research workforce. For example, data from NIH on the number of physicians supported on T32 institutional training grants, receiving K01 Mentored Research Career Development Awards,8 and awarded R019Equivalent research grants are currently unavailable (Garrison and Ley,

___________________

8 “K awards provide support for senior postdoctoral fellows or faculty-level candidates. The objective of these programs is to bring candidates to the point where they are able to conduct their research independently and are competitive for major grant support.” A K01 award is the colloquial name for the Mentored Research Scientist Development Award, which “supports 3 to 5 years of mentored research training experience in the biomedical, behavioral, or clinical sciences. NICHD accepts K01 applications for only three research areas: Rehabilitation Research, Child Abuse and Neglect, and Population Research” (NICHD, 2023b).

9 The R01 is historically the oldest and most common grant mechanism used by NIH; R01s are for “mature research projects that are hypothesis-driven with strong preliminary data” and provide up to 5 years of support (NIH, 2023a).

2022; see section on NIH funding). The NIH Physician–Scientist Working Group last met in 2013 and there has not been an updated report since then, let alone one specific to the pediatric physician–scientist workforce. There is also a stark lack of communication and collaboration among funding agencies and other participants in the research enterprise to target important areas of pediatric research.

More information on the composition of career development awards and tracking of research careers by demographic factors such as sex, race and ethnicity, disability status, geography, type of science across the continuum (e.g., basic, clinical, implementation), topic/subspecialty, and professional background of the principal investigator (PI) is needed to truly quantify the pediatric physician–scientist workforce and to understand trends. There is also little to no tracking of outcomes from pediatric physician–scientist career development pathway programs. In addition to these quantitative data, qualitative data (e.g., on successful researchers as well as those researchers who leave the research track, including quality of relationship with mentors, satisfaction with career progression, reasons for attrition or retention) will be critical for retention of successful pediatric physician–scientists. During one of the committee’s public webinars, Ericka Boone, director for the Division of Biomedical Research Workforce, Office of Extramural Research, NIH, highlighted the need for data on the workforce and barriers to the pathway:

The only way we can have a clear understanding of what these barriers are is if we ask the individuals that are engaging in these research careers, especially those individuals who have exited out of the research career. What were those things? What were those barriers that just said, I can’t do this anymore?…Why are we losing postdocs? Why are we losing early career investigators? Why are they exiting out of these careers? And then doing something to keep them in.10

See Box 6-4 for clinician perspectives on the need for physician–scientists.

Trends in Research Work Profiles by Subspecialty

There are considerable disparities in the proportion of physicians who spend a significant amount of time in research activities across the pediatric subspecialties, and the data available are mostly self-reported (typically through ABP’s maintenance of certification process). As noted in Chapter 4, data from 2018–2022 reveal that among the ABP-certified pediatric

___________________

10 The webinar recording can be accessed at https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/11-02-2022/the-pediatric-subspecialty-workforce-and-its-impact-on-child-health-and-well-being-webinar-3.

subspecialists overall, less than 8 percent reported spending more than 50 percent of their time on research, and 48 percent reported not being involved in any research activities (ABP, 2023). Additionally, the amount of time dedicated to research varies across the subspecialties. ABP-certified subspecialties with the highest percentage of clinicians spending 50 percent or more of their time to research include hematology/oncology (21.6 percent), infectious disease (19.3 percent), rheumatology (14.2 percent), pulmonology (10.8 percent), and endocrinology (10.6 percent) (ABP, 2023). At the extremes, nearly 12 percent of hematology/oncology subspecialists spent 75 percent or more of their time on research while 69 percent of hospital medicine subspecialists reported spending no time on research. Macy et al. (2020) examined ABP’s maintenance of certification data from 2009–2016 and found that the number and proportion of pediatric subspecialists

engaged in research has not increased or decreased over the study time period, suggesting that previous efforts to bolster the pediatric physician–scientist workforce have not made a difference in increasing this segment of the workforce.

CHALLENGES TO THE PHYSICIAN–SCIENTIST WORKFORCE AND INTERVENTIONS TO SUPPORT PEDIATRIC RESEARCHERS

Pediatric physician–scientists continue to accelerate new basic science and medical insights, behavioral discoveries, and organizational effectiveness. However, the system for producing and nurturing physician–scientists has been inadequate, with limited funding, and heightened clinical and teaching demands (Salata et al., 2018; Williams et al., 2022). The shortage of resources available to support early career pediatric physician–scientists, combined with the multitude of influences on personal career decisions (see Chapter 5) and the demands of clinical practice, has resulted in a decreasing and aging workforce of pediatric researchers, with concerns for the viability of the workforce (Speer et al., 2023). Additionally, retention of physician–scientists in the mid-career space is also a major concern. While the committee has recommended increased flexibility in training curriculum including clinical-only tracks (see Chapter 5), it is critical to also continue to invest in pediatric researchers and to use strategies for improved recruitment and retention of pediatric physician–scientists. For example, flexible training curricula might allow for earlier exposure to research to help support the pediatric physician–scientist pathway.

Since 2017, Pediatric Research has published a series of commentaries that provide an opportunity for early career investigators to share experiences or inspirations that influenced their career path, thoughts on what contributed to their success or choices, and advice to others who are in early stages of their career (El-Khuffash, 2017; Guttmann, 2022; Harshman, 2021; Lovinsky-Desir, 2019; Menon, 2021; Salas, 2020; Sun, 2021). For many, early encounters with the medical or the health field, formative research experiences, patient encounters that informed research questions, and inspiring mentors helped fuel and define interest in medicine and/or research careers. Other key factors that influence early career physician–scientists include acquiring the needed academic and professional skills and training, resources, and protected time, and learning from failure (Christou et al., 2016; Flores et al., 2019; Ragsdale et al., 2014).

Threats to the sustainability and growth potential of the physician–scientist workforce and to pediatric research more broadly include: (1) lack of structured and sufficient mentorship and training, most significantly, but not exclusively, for fellows and early career investigators; (2) financial considerations (e.g., educational debt) that impact trainees’ decision to

pursue research; (3) protection of time for physician–scientists to engage in research; and (4) adequate funding (both extramural and institutional) for research (Alganabi and Pierro, 2021; Permar et al., 2020).

Specific efforts are needed to encourage and facilitate entry into research careers and foster the early phases of career development for pediatric physician–scientists. This is especially true for physician–scientists from populations underrepresented in the extramural scientific workforce (including the biomedical, clinical, behavioral, and social sciences workforces) (NIH, 2022b), which includes certain racial and ethnic groups, individuals with disabilities, individuals from economically disadvantaged backgrounds, and others (depending upon the discipline).

Academic physician–scientist retention is also distressingly low regardless of the mechanism of training (Williams et al., 2022), so efforts for retention of pediatric physician–scientists are also critical. The following sections provide an overview of several of the challenges faced by the pediatric research workforce, including mentorship financial considerations and protection of time, as well as interventions to increase representation in the research workforce. The adequacy and distribution of funding for research itself is discussed after this section.

Mentorship and Training

The importance of mentorship in career success and in advice to new researchers are highlighted in the Pediatric Research commentaries discussed above. The authors advise being intentional about seeking out skilled mentors to support the growth and development of the early career investigator, in addition to building a network of support that includes other investigators, peer mentors, and family and friends (El-Khuffash, 2017; Guttmann, 2022; Harshman, 2021; Lovinsky-Desir, 2019; Menon, 2021; Salas, 2020; Sun, 2021). Gaps in mentorship for physician–scientists exist across the entire professional timeline.

Medical School

In medical school, research often is introduced later in training, often too late for an individual to develop strong mentorship and pursue an area of scholarly interest in depth prior to the start of residency training. In 2020, medical school curriculum pathways from 145 schools were reviewed, and numerous examples of research opportunities for medical students were highlighted (McOwen et al., 2020). Some of the opportunities were explicitly research while others were a component of an optional or required scholarly concentration program rather than research in the traditional sense (McOwen et al., 2020; Thompson et al., 2020). Overall,

there has been a decline in the aspirations of graduating medical students to pursue research, which may be a result of curricular reforms that place increased emphasis on clinical decision making, and a decreased emphasis on foundations in basic science (Buja, 2019; Garrison and Ley, 2022). However, medical schools have also developed initiatives to bolster the number of physician–scientists. More than 30 medical schools have Physician–Scientist Training Programs (PSTPs) that integrate residency, fellowship, and postdoctoral training for trainees that commit to a physician–scientist career path (Garrison and Ley, 2022; Muslin et al., 2009), though only a small proportion of medical school graduates enter PSTPs (NRMP, 2023).

Residency and Fellowship Training

Not all residency training programs or specialty fellowships provide focused mentorship opportunities for research, which can limit the exposure of trainees to adequate career mentors. “In certain large non-university medical centers with expansive clinical outlays—which focus predominantly on the clinical mission as a driver (and determinant) of research activities—it is relatively rare to have physician–scientists on faculty in clinical departments, further limiting the role models for this career” (Williams et al., 2022). Residents are immersed in intense clinical training with relatively little time for or training in research, with a curriculum that emphasizes information relevant to clinical care and is largely defined by national medical board standards. Many residency programs lack a dedicated research track for physician–scientists, and there are insufficient guidelines, or dissemination of best practices, from the pediatric research community on research training and mentorship. The PSTP programs provide research training opportunities for both M.D. and M.D.-Ph.D. trainees both during or after the completion of clinical training (Williams et al., 2022). Some fellowship programs provide more comprehensive research experiences. While clinical competency must be ensured, greater exposure to research at this stage increases the chance of developing into a successful physician–scientist (Rubenstein and Kreindler, 2014). One possible solution is to encourage trainees to participate in extra years of fellowship; however, there are significant financial disincentives to remaining in training (at fellowship income levels) by comparison to opportunities for faculty or clinical positions (Rubenstein and Kreindler, 2014).

In 2022, the National Pediatric Scientist Collaborative Workgroup, a collaborative of leaders in pediatric research and medical education, surveyed pediatric residency program directors about barriers to developing physician–scientists. Three priority areas were identified: (1) institutional infrastructure, human resources, and financial resources to develop

physician–scientist training; (2) “dual professional identity formation” of the pediatric physician–scientist; and (3) input and pathway of candidates into this career path (Burns et al., 2022). This workgroup has begun to develop efforts to address these areas by creating guidelines for best practices in physician–scientist training. Other organizations, such as the Burroughs Wellcome Trust,11 also have invested resources into bolstering the M.D.-only researcher pathway through early career awards and career development workshops. There are other programs as well, such as the consortium funded National Clinician Scholars Program,12 which supports physicians and nurses through a two-year site-based research training fellowship (NCSP, 2023) and the Doris Duke Physician Scientists Fellowship program, which provides grants to physician–scientists at the subspecialty fellowship level who are seeking to conduct additional years of research beyond their subspecialty requirement (Doris Duke Foundation, 2023).

The relatively new NIH pilot program, “Stimulating Access to Research in Residency (StARR)” (R38) was initiated in 2017 to create new research opportunities for residents during their clinical training in efforts to recruit resident investigators and increase the body of clinician investigators. Hurst et al. (2019) describes a single institution’s pediatric physician–scientist development program, supported in part by an NIH R38 StARR award, that affords research-integrated training across the spectrum of research, for trainees interested in academic general pediatrics or a pediatrics subspecialty and includes support regarding mentor and mentorship teams, scholarly oversight committees, research productivity, educational enrichment, and professional development. The National R38 Consortium consists of principal investigators (PIs) and multiple principal investigators from the first round of R38 awards that were granted in 2018. In a report of early outcomes, PIs endorsed institutional commitment of new resources to support the program and viewed the program positively regarding enhancing research opportunities and recruitment, although there is a need to increase the pool and appointees from populations underrepresented in the extramural scientific workforce (Price Rapoza et al., 2022). After R38 appointment, resident investigator respondents reported a number of positive outcomes, including likelihood of pursuing a physician–scientist career, clarity of research direction, and expanded mentorship.

___________________

11 For more information about the Burroughs Wellcome Trust, see https://www.bwfund.org/ (accessed June 27, 2023).

12 This consortium was grown out of the previous Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars program.

Early Career

Mentored time immediately after completion of fellowship during the first years of faculty appointment is critical. Mentored research training programs with a focus on fellows and/or early career faculty are offered in multiple settings, including individual institutions, national NIH or foundational programming, and pediatric specialty or subspecialty societies (Badawy et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2016; Cranmer et al., 2018; Kashiwagi et al., 2013; Vasylyeva et al., 2019). Of note, NIH has an embedded component of mentorship through the K-series awards with a requirement that applicants designate mentors and specify a formal mentoring plan (DeCastro et al., 2013; NIAID, 2021). Chen et al. (2016) described the multifaceted “Pediatric Mentoring Program” implemented for instructors and assistant professors in an academic pediatrics department with the goal of promoting retention and job satisfaction. The program consisted of mandatory annual/biannual mentor meetings as well as grant review assistance and peer-group mentoring and annual evaluations. The majority of participants described benefits related to understanding of criteria for advancement or progress toward career goals, but only a minority reported developing collaborations with peers or improved work–life balance. King et al. (2021) described self-reported benefits of participation in a one-year mentored clinical research training program for hematology/oncology fellows and early career faculty (pediatric and adult). Most participants endorsed the program as instrumental to retention in hematological research and facilitation of career development in research; those who endorsed a positive program impact performed better on conventional research metrics such as first author publications and percentage of effort in research when compared with the minority of participants who did not endorse positive program impact.

Mid-Career

While most formal mentoring programs are targeted towards early-career researchers and junior faculty, mentorship is also important in the mid-career space, particularly for female researchers and other populations underrepresented in the extramural scientific workforce (Bora, 2023; Lewiss et al., 2020; Sotirin and Goltz, 2023; Teshima et al., 2019). In academic medicine overall, high-quality mentorship is essential to faculty productivity, job satisfaction, and retention, as well as academic advancement (AAMC, 2023b; Bland et al., 2010; Mylona et al., 2016; Walensky et al., 2018). However, few universities have instituted formal mid-career mentoring programs, let alone mid-career programs specific to the pediatric scientific workforce, and mid-career physician–scientists have reported a lack of high-quality mentoring (Bora, 2023; Pololi et al., 2023). Specific

to pediatrics, a discussion-based workshop at the American Society of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology annual meeting found that mid-career participants frequently lacked mentors and thought that “mentors did not appreciate the complexity of the mid-career role” (Frugé et al., 2010).

Financial Considerations

Choosing a career as a physician–scientist is likely influenced by the loss of opportunities for higher salaries both because of extended periods of training (leading to deferred entry into faculty positions) and comparatively higher salaries for private practice (Donath et al., 2009; Pickering et al., 2014; Rosenberg, 1999; Somekh et al., 2019). For example, Zemlo et al. (2000) found that a rising level of student debt in the 1990s was correlated with a declining proportion of physicians choosing research careers. Physician–scientists can incur major debts because of the extra training time needed to gain expertise for both research and clinical care. As mentioned earlier, M.D.-Ph.D. programs may be more attractive for trainees due to the free tuition and avoidance of medical school debt. This incentive is not typically given for M.D.-only investigators, though several medical schools have begun to cover some or all of the cost of tuition through dedicated endowments. Additionally, salaries for pediatric physician–scientists can also be negatively affected by less clinical incentive income and low pay lines in awards. For example, career development awards (e.g., K-series awards) cover some salary support, but this often needs to be supplemented with cost sharing by the physician–scientists’ institutions (Daniels, 2015; Garrison and Deschamps, 2014; NIH, 2017a). Given the relatively lower clinical margin in pediatric departments, this issue may be particularly difficult for pediatric physician–scientists. (See Chapter 8 for more information.) During one of the committee’s public webinars, Mary Leonard, Arline and Pete Harman Professor and Chair of the Department of Pediatrics at Stanford University, director of the Stanford Maternal and Child Health Research Institute, and physician-in-chief of Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital, highlighted how financial considerations play a role in pursuing a pediatric research career: “Going the physician–scientist route defers compensation even further. You have longer trained intervals. In some places, you have lower salaries.”13 See Box 6-5 for clinician perspectives on the financial challenges for pediatric physician–scientists.

___________________

13 The webinar recording can be accessed at https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/07-19-2022/the-pediatric-subspecialty-workforce-and-its-impact-on-child-health-and-well-being-webinar-1.

NIH Loan Repayment Programs (LRPs) and Impact on Research Careers

Loan repayment for pediatric researchers is one approach to overcome financial barriers to entering or remaining in pediatric subspecialty research careers. During the committee’s public webinars, Stephanie Lovinsky-Desir, assistant professor and chief of the Pediatric Pulmonary Division at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital of New York Presbyterian discussed the role of loan repayment to help alleviate financial disincentives to pursuing a pediatric research career:

I applied for the NIH loan repayment program…it was really instrumental toward me staying in a field of pediatric research…a loan repayment that could help offset some of the burden that I have actually was helpful in making the decision to be able to remain in academia and remain in a research-intensive tract…loan repayment is super important for someone like me who didn’t benefit from generational wealth, and I have a ton of

debt, and so I’m not quite finished, I’m 10 years out of fellowship training, paying down all of those loans, even with the loan repayment.14

Since 1988, the NIH LRPs have supported early-stage investigator awardees in their pursuit of biomedical and behavioral research, including repaying up to $50,000 in educational loans per year in exchange for a commitment to research for at least 20 hours per week for at least 2 years (with possibility for renewal) (Lauer, 2019; NIH, 2022c). From FY2013 to FY2022, there were 3,105 LRP awards in pediatric research, with a 52 percent success rate overall (40 percent for new awards and 71 percent for renewal awards) and total funding of $177,264,184 (with over $105 million of that going to new awards) (NIH, 2023d). In FY2022, the mean award for new pediatrics applications was $88,669 while the mean for renewals was $47,720; the mean age of new awardees was 36 years (NIH, 2023d).

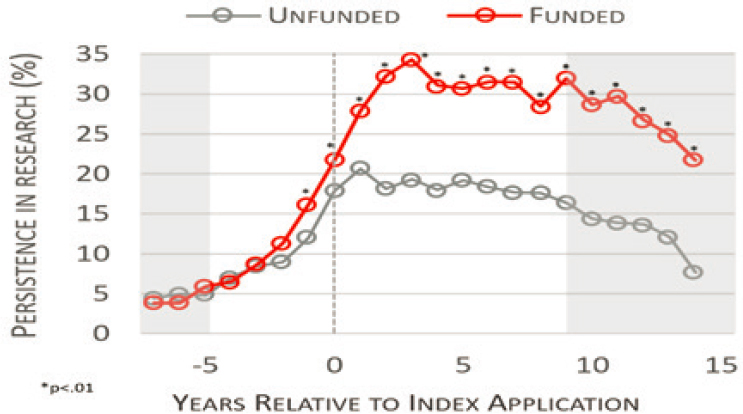

Lauer (2019) compared research-related outcomes between applicants who received and did not receive an LRP award (during fiscal years 2003–2009) with follow-up of research productivity through 2017 (see Figure 6-2). The author reported that receipt of an LRP award was associated with higher levels of “persistence in research” (composite measure including

SOURCE: Adapted from Lauer, M. 2019. Reproduced with permission from the NIH Open Mike Blog.

___________________

14 The webinar recording can be accessed at https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/07-19-2022/the-pediatric-subspecialty-workforce-and-its-impact-on-child-health-and-well-being-webinar-1.

submission or receipt of grant or fellowship awards and publications) over a decade after initial application. Although confounding factors may contribute to findings, Lauer noted the NIH LRP Program is an important potential strategy for retention of early career investigators in the research workforce.

Across all NIH LRPs (including non-pediatric awards) in 2022, more than half of awardees had a total education-related debt of over $200,000 (NIH, 2023d). The NIH LRP is an attractive option to encourage the pursuit of a research career.

Protection of Research Time

The time required for pediatric subspecialists to be successful as physician–scientists can be substantial. Historically, a physician–scientist profile has required that 50 percent of one’s professional time be focused on research, but with increasing clinical demands and the need to fund this protected research time, a growing number of physicians are conducting research with less time allocated to the effort. NIH requires K-awardees to devote at least 75 percent FTE to research. However, only 3.4 percent of subspecialists report spending at least 75 percent of their time in research (ABP, 2023). Most individuals with R-level grants are devoting at least 50 percent of their time and often much more to research in order to be successful and competitive, yet only 7.6 percent of subspecialists report working at least 50 percent of their time on research (ABP, 2023).

Faculty physician–scientists balance many priorities, including teaching, clinical care, administration, and research. As the competition for securing extramural funding and meeting clinical productivity requirements continues to intensify, it has become increasingly difficult to maintain a career that adequately balances research and clinical care (COPR, 2014). Protection of research time allows physician–scientists to be freed from clinical duties to pursue research. Career development and training awards offer a safeguarded period for emerging scientists to establish a research program with protected research time in order to ultimately reach a point where they can independently conduct research with their own funding support (Garrison and Ley, 2022). Training awards, either institutional (e.g., T32/K12 grants) or individual (e.g., K series grants), require protection of at least 75 percent of their time.

T32 institutional training program grants are made to institutions to support groups of pre- and/or postdoctoral fellows and K12 institutional career development institutional grants (e.g., for PDSPs) aim to prepare newly trained physicians who have made a commitment to independent research careers by providing support to institutions that mentor clinical fellows and scientists (Garrison and Levy, 2022; NICHD, 2023a). Success of

a T32 program can be difficult to measure. A NICHD task force that conducted an in-depth review of its extramural training programs and mechanisms found that individuals supported by T32 programs had less-favorable outcomes when compared with individuals supported at the career level (either through individual K or institutional K12 grants) (NICHD, 2015; Steinbach et al., 2018). On the other hand, Abramson et al. (2021) found that having a T32 training grant doubled the probability that pediatric subspecialty fellows published during their fellowship. Historically, NICHD has “emphasized the institutional training and career development awards to a greater degree than many other NIH institutes and centers” and strongly invested in K12 development programs (Twombly et al., 2018).

However, the NICHD task force that reviewed its extramural training programs recommended placing more emphasis on individual awards compared with institutional training awards (NICHD, 2015; Steinbach et al., 2018), and NICHD announced their intention to allocate a greater proportion of its career development fund allocation to individual awards (Twombly et al., 2018). There are a variety of individual K programs targeting specific career stages and research areas. The largest programs are:

- K01 Mentored Research Scientist Career Development Award,

- K08 Mentored Clinical Scientist Research Career Development Award,

- K23 Mentored Patient‐Oriented Research Career Development Award, and

- K99 Pathway to Independence Award.

While M.D.s can apply for any of these awards, they are most often supported by the K08 and K23 mechanisms, which comprise approximately half of all K awards (Garrison and Ley, 2022). Estimates suggest that at least 3,000 physicians were supported on career development awards each year from 2011 through 2020, though there has not been an increase in career development awards targeted to physicians (Garrison and Ley, 2022). The number of pediatricians, let alone pediatric subspecialists, is unknown. (See the section on NIH in the funding section in this chapter for more information.)

Previous reports that have looked at bolstering the physician–scientist workforce have proposed increases in the number of career development awards so that early career physician–scientists have the necessary supports to initiate successful research programs (Jain et al., 2019; NIH, 2014; Salata et al., 2018). Multiple studies across different specialties have shown that NIH K awardee are more likely to receive subsequent, independent NIH awards than medical school graduates without them (Jeffe et al., 2018; King et al., 2013; Nikaj and Lund, 2019; Okeigwe et al., 2017). Funding

rates for K-series awards vary widely by NIH institute and federal agencies (e.g., the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ]) and by year, with success rates typically ranging from 20 to 40 percent in a given cycle and many investigators requiring multiple submissions before receiving funding (AHRQ, 2016; Conte and Omary, 2018; NIH, 2023c). Those engaged in research without such funding sources may struggle to allocate sufficient time for investigation, leading to increased burden of professional responsibilities and risk for burnout. Most pediatric departments do not have the resources to support a sizeable amount of research time for more than a limited number of years. As careers progress, the cost of providing the “over the NIH cap” component of the salary can lead to increased pressure to perform clinical work instead of research, unless discretionary funds such as endowed professorships are provided to cover these costs, but these clinical requirements erode protected time.

Increasing the Diversity of Pediatric Researchers

As discussed in Chapter 5, to mirror the demographic make-up of the children and families it serves, the pediatric workforce will require special attention for the recruitment and retention of a diverse set of trainees; this is especially true for the pediatric research workforce. There is evidence that “scientific teams that are composed of diverse individuals with diverse perspectives, backgrounds, and mental models are better positioned to solve complex problems among children and their families” (Guevara et al., 2023), and are more likely to engage in research with diverse groups and communities and generate higher quality research (Ayedun et al., 2023; Campbell et al., 2013; Page, 2007). However, the number of pediatric physician–scientists from populations underrepresented in the extramural scientific workforce is small and growing at a slow rate (AAMC, 2019; Guevara et al., 2023; Lett et al., 2018), though exact statistics are not available. A principal recommendation of the NIH Physician–Scientist Workforce Working Group Report was to improve diversity among all researchers (NIH, 2014). However, structural, systemic, and cultural barriers exist for trainees and faculties from populations underrepresented in the extramural scientific workforce that limit entry or reduce retention in this career path (Behera et al., 2019), including limited opportunities for mentorship and mentorship training, bias and discrimination, and systemic factors at the institutional level (Kalet et al., 2022; Siebert et al., 2020). Minority academic pediatricians have identified a range of obstacles that impede the successful recruitment and retention of minority physicians, including insufficient financial resources, ineffective recruitment strategies, limited opportunities for career advancement, fewer research resources, and inadequate research support (Johnson et al., 2017b; Saboor et al., 2022). Other key

issues that threaten the retention of physician–scientists from populations underrepresented in the extramural scientific workforce include disparities in personal wealth, excessive service demands to provide diverse perspectives in committees and conferences, feelings of isolation arising from intersectionality, and apprehensions regarding reinforcing stereotypes (Kalet et al., 2022).

Strategies that have been suggested to promote representation in the research workforce include institutional antiracism policies; support for trainees and faculty from populations underrepresented in the extramural scientific workforce; encouraging diversity in public engagements and institutional leadership; providing child/elder care subsidies; tracking diversity outcome measures; and developing “diversity aware” training curricula (Williams et al., 2022). Interventions include faculty development programs like the Research in Pediatrics Initiative on Diversity, which is a national program of the Academic Pediatrics Association that provides mentoring, research training, and career development for URiM junior pediatrics faculty, and has resulted in increased grant productivity and promotion of participants (Flores et al., 2021). Pediatric departments and children’s hospitals, especially with national discussions of racism in society and medicine after the May 2020 murder of George Floyd, have recognized the need to address equity, diversity, and inclusion in all their activities, including the composition of faculty investigators (Pursley et al., 2020; Walker-Harding et al., 2020; Wright et al., 2020). Institutions are addressing diversity in a number of ways, all of which have the potential to be accelerated:

- Recruiting a much more diverse residents’ workforce, realizing that their own residency program is an important source of potential fellows.

- Recruiting more diverse fellows, recognizing that graduating fellows are an important source of future faculty.

- Creating fellowship opportunities specifically for populations underrepresented in the extramural scientific workforce.

- Creating internal K-12–like individual career development programs specifically for populations underrepresented in the extramural scientific workforce.

- Providing start-up packages for faculty that increase the chance of success in their research.

- Ensuring that appropriate and intensive mentoring is available for populations underrepresented in the extramural scientific workforce at each stage in their careers.

Given the importance of mentoring in the professional growth, development, and success of trainees and early career investigators—and the potential impact on racial disparities in R01 success (Ginther et al., 2011)—it is

important to support mentors in their efforts to gain the knowledge and skills needed to be effective mentors for trainees from diverse backgrounds, particularly for trainees from backgrounds underrepresented in the biomedical research workforce, as well as recognizing mentoring efforts and excellence (NASEM, 2019). Efforts such as the National Research Mentoring Network created/fostered opportunities for mentors and mentees to improve relationships through competency-based trainings offered in multiple types of settings and platforms, including Culturally Aware Mentoring (Byars-Winston et al., 2018; Sorkness et al., 2017).

Across all disciplines, there has been evidence that Black scientists are less likely to receive NIH funding when compared with White scientists (Ginther at al., 2011; Ginther, 2022). As discussed previously, career development awards are an important lever to support early career researchers. An analysis of the race-ethnicity of NIH K awardees from 2010 to 2022 found that while the numbers of Black and Hispanic applicants and awardees have steadily increased over time, the total number of Black and Hispanic applicants remains “quite low” (Lauer and Bernard, 2023). Notably, K award funding rates for Black applicants have increased over the past 3 years. NIH has taken steps to address racism in the scientific workforce and improve diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts (NIH, 2021). For example, the NIH UNITE Initiative was established to address structural racism and establish equity within the biomedical research enterprise (NIH, 2022d). The Extramural Research Ecosystem: Changing Policy, Culture and Structure to Promote Workforce Diversity Committee is charged with performing systematic reviews of NIH extramural policies and processes to identify areas for policy change to address the lack of diversity and inclusivity within the extramural research ecosystem. Priorities include supporting career pathways, research resources, and capacity at minority-serving institutions,15 promoting equity at extramural institutions in regard to environment and culture, and encouraging equity in policies and procedures at NIH.

Mid-Career Concerns and Retention

This chapter largely focuses on the early phases of the pediatric physician–scientist pathway, emphasizing that early career mentorship, protected research time, and funding are critical supports for entry into a research career, and these can lay a foundation to promote longevity over time. However, mid-career retention of physician–scientists and difficulties during the transition from career development (K series) awards to

___________________

15 MSIs are institutions of higher education that serve minority populations. See https://www.doi.gov/pmb/eeo/doi-minority-serving-institutions-program (accessed July 18, 2023).

independent research grants (R series) (the ‘K to R transition’) remain a major area of challenge (Daye et al., 2015; Good et al., 2018a; Yin et al., 2015), although exact data on attrition rates by pediatric subspecialists during this transition are lacking. Retention of pediatric physician–scientists is threatened by burnout, inadequate mentoring, an increasingly competitive funding environment, financial pressures related to loan repayment and salary, inadequate institutional support and protected time for scholarship, and difficulties balancing clinical and research demands, among other factors (Alvira et al., 2018; Bauserman et al., 2022; Christou et al., 2016; Rosenthal et al., 2020; Salata et al., 2018; Shafer, 2010). (See Chapter 5 for more information on clinician burnout.)

The K to R transition has been described as “tortuous and prolonged,” due to low success rates for R series awards and funding gaps (Yin et al., 2015). Women tend to be disproportionately affected at this transition point (Jagsi et al., 2009, 2011; Ghosh-Choudhary et al., 2022; NIH, 2014). Nguyen et al. (2023) found that women received 43 percent of all K awards from 1997–2011 and 34 percent of awards from 2012–2021. Funding rates were lower than faculty representation rates in 5 of the 13 departments assessed, including pediatrics. Regarding K to R transition, 37.7 percent of women who received mentored K awards between 1997 and 2011 successfully applied for R01-equivalent grants within 10 years, compared to 41.5 percent of men (Nguyen et al., 2023).

NIH has created a K99/R00 funding mechanism that incorporates the transition into the funding period (NCI, 2023c), but much of the burden of supporting this transition period falls on institutions, as the investigators require protection of time and financial resources to maintain a research team and program. Many institutions hold K to R transition workshops with programs such as mock grant review/study sections, structured mentoring for grant and manuscript preparation, and information about securing ancillary funding16 (Jones et al., 2011; Yin et al., 2015). While such guidance is helpful, physician–scientists often require protection of time from clinical activities and bridge funding to ensure that their research can continue if there is a lapse in funding. This is a substantial financial investment to which pediatric departments often cannot commit due to financial pressures, so pediatric physician–scientists may be particularly vulnerable during the K to R transition period. Given the current data limitations, it is important to collect more data on the rates of attrition across the pediatric

___________________

16 For examples, see https://ictr.johnshopkins.edu/education-training/seminars-courses/k-tor/ (accessed July 18, 2023), https://learn.partners.org/courseversion/922/ (accessed July 18, 2023), https://catalyst.harvard.edu/courses/grasp (accessed July 18, 2023), and https://tracs.unc.edu/index.php/services/education/r-writing-group (accessed July 18, 2023).

subspecialties, as well as evidence-based interventions for a successful K to R transition, in order to develop data-driven policies to address these issues.

THE PEDIATRIC RESEARCH FUNDING LANDSCAPE: ADEQUACY AND DISTRIBUTION

Funding is the greatest challenge to the physician–scientist workforce. The federal government—particularly NIH—is a significant funder of child health research in the United States. Other major sources of funding for pediatric research include other federal agencies, private foundations, state and local governments, pharmaceutical companies, device manufacturers, and biotechnology firms. Academic medical centers also bear many of the costs of training physician–scientists and supporting their research efforts. There is an increasing move to align efforts across various funding organizations to maximize resources and avoid redundancy, although currently there is little coordination or collaboration among funders. Additionally, as discussed in more detail below, physician–scientists rely on institutional support to build and maintain the basic infrastructure (e.g., personnel, space, equipment, and salary) for a sustainable research program.

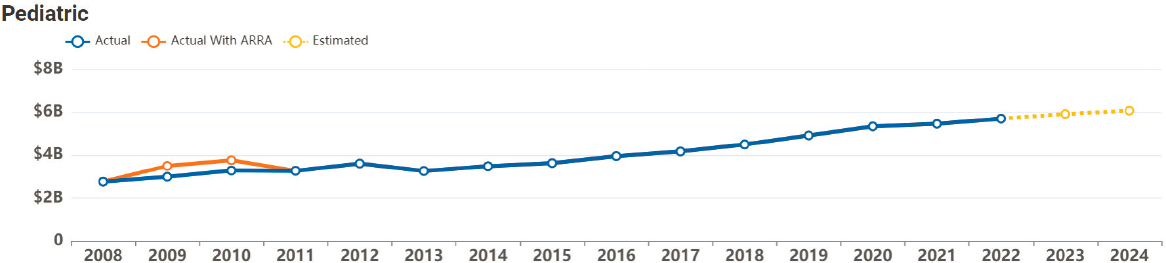

NIH

NIH remains the largest government funding source for global biomedical research (Rees et al., 2021). Historically, pediatric research funding has been low compared with funding for adult diseases, though it has been increasing along with the requirements for NIH to report pediatric research spending annually (Gitterman et al., 2004, 2018a, 2023; Speer et al., 2023). Nearly all of NIH’s 27 institutes and centers fund child health research, with NICHD supporting the largest proportion of the pediatric portfolio (approximately 18 percent in 2021–202217) (Gitterman et al., 2018b; NICHD, 2022d; NIH, 2017b). Since 2013, annual NIH support for pediatric research has increased, with $5.7 billion allocated in 2022 (see Figure 6-3). NIH funding for child health has generally kept pace with overall NIH funding increases in absolute dollar amounts18 (Boat and Whitsett, 2021). While the total dollars spent on pediatric research has increased, the percentage of total NIH funding specific to pediatric research has remained steady at approximately 11 to 12 percent of the total NIH

___________________

17 Estimate provided to the committee by Rohan Hazra, NICHD, on May 11, 2023.

18 The overall NIH budget increased from $29 billion for FY2013 to $49 billion for FY2023. NIH funding adjusted for inflation (in projected constant FY2022 dollars) using the Biomedical Research and Development Price Index showed a smaller overall increase, from $36 billion in FY2015 to $47 billion in FY2023 (Sekar, 2023).

NOTES: 2023–2024 are estimates. ARRA = American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, Public Law No. 111-5, 111th Congr., H.R. 1 (February 17, 2009)).

SOURCE: NIH, 2023b.

budget for the past decade (not adjusted for inflation).19 The number of applications for NIH awards by medical school pediatric departments has been steady from 2012 to 2019 (approximately 1,400 per year, with 16 to 21 percent of applications funded) (NIH, 2023c). There was a drop in applications in 2020 and 2021, with a rebound in the number of applications in 2022 to approximately 1,300 applications and a 20 percent success rate (NIH, 2023c).

NIH Research Funding by Subspecialty

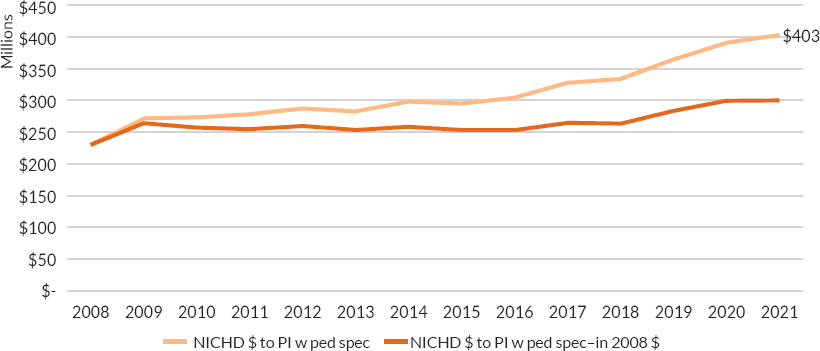

NICHD funding for principal investigators with pediatric subspecialty fellowship training has risen steadily over time, with the largest increases coming in the past 4 years (see Figure 6-4).

Objective data on funding by pediatric subspecialty are not readily available, but self-reported survey data suggest that NIH research funding is not equally distributed across the different subspecialties in terms of total funding, proportion of R01-equivalent investigators, and other indicators (Good et al., 2018b). Good et al. (2018b) found that among the 907 R01-Equivalent Pediatric Physician–Scientist Awardees from 2012 to 2017, the highest percentages were in hematology/oncology, academic general pediatrics, and infectious disease (see Table 6-2). These differences across subspecialties warrant further exploration as they likely reflect a variety of factors, including the foundational tradition that these subspecialties have of doing research, uneven funding allocations for research in certain subspecialties, and the weakened research workforce pathway in certain subspecialties.

The critical role of the home institution in supporting research limits the scope of research activities in smaller, less academic institutions. Eligibility for some NIH awards requires institutions of higher education, often compelling freestanding children’s hospitals to apply through other institutions which, in turn, creates more administrative inefficiencies, costs, and hurdles. Furthermore, the lower reimbursement rates for pediatric clinical care (see Chapter 8) leaves limited resources for institutions to support research. These funding challenges have resulted in major disparities in the distribution of research activities across institutions, with the largest children’s hospitals with the strongest institutional infrastructure for research accounting for the majority of NIH-funded activities (see Table 6-3) (Good et al., 2018b). This disparity undermines the physician–scientist pathway in smaller institutions, especially those not associated with large academic centers, even though children in these locales would benefit equally (and

___________________

19 Estimate calculated using pediatric funding data from NIH (2023b) and overall NIH budget data from Sekar (2023); estimates not adjusted for inflation.

NOTES: Figure includes dollars from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. (American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, Public Law No. 111-5, 111th Congr., H.R. 1 (February 17, 2009)).

Funding levels were adjusted for inflation in research costs using the Biomedical Research and Development Price Index (BRDPI). For more information on BRDPI, see https://officeofbudget.od.nih.gov/gbiPriceIndexes.html.

SOURCE: Provided to the committee by Rohan Hazra, NICHD, on September 9, 2022. NICHD’s Child Health Information Retrieval Program (CHIRP): These are not official NIH-wide data.

TABLE 6-2 Pediatric Division Representation Among the 907 R01Equivalent Physician–Scientist Awardees, 2012–2017

| Pediatric Subspecialty | R01-Equivalent Awardees, No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Hematology/oncology | 146 (16.1) |

| Academic general | 109 (12.02) |

| Infectious disease | 93 (10.25) |

| Neonatology | 82 (9.04) |

| Endocrinology | 49 (5.4) |

| Neurology | 46 (5.07) |

| Pulmonology | 45 (4.85) |

| Gastroenterology | 44 (4.85) |

| Genetics | 39 (4.3) |

| Cardiology | 36 (3.97) |

| Nephrology | 32 (3.53) |

| Critical care | 31 (3.42) |

| Allergy and immunology | 31 (3.42) |

| Rheumatology | 15 (1.65) |

| Adolescent | 14 (1.54) |

| Behavioral and development | 10 (1.1) |

| Emergency medicine | 10 (1.1) |

| Non-pediatric primary training | 75 (8.27) |

NOTE: Physician–scientists who had not completed a residency in pediatrics were considered “non-pediatric primary training.”

SOURCE: Good et al., 2018b. Reproduced with permission from JAMA Pediatrics. Copyright ©2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

perhaps more) from enrollment in investigational efforts, such as natural history studies, interventions, and clinical trials.

NIH funding to pediatric institutions and programs continues to be increasingly concentrated in a few sites. Boat and Whitsett (2021) analyzed the 2020 NIH Reporter data and found that 30 percent of NIH’s $1.96 billion funding to pediatric institutions and programs went to 3 children’s hospitals and 57 percent to the top 10 NIH grant recipients. Between 2013 and 2020, NIH funding of research to the top 10 grant recipients increased 93 percent while funding to those in the third and fourth deciles increased by about 10 percent (Boat and Whitsett, 2021). About one-third of pediatric departments have no NIH funding and more than half (57 percent) have five or fewer NIH grants. Factors differentiating the more and less well-funded programs include local institutional investments in research training, research leadership, and research faculty (Boat and Whitsett, 2021).

TABLE 6-3 Institutional Distribution of Pediatric R01-Equivalent Awards, 2012–2017

| Institutions with R0-1 Equivalent Awards | Number of Awards |

|---|---|

| Boston Children’s Hospital | 326 |

| Cincinnati Children’s Hospital | 289 |

| Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia | 184 |

| Seattle Children’s Hospital | 103 |

| Baylor College of Medicine | 78 |

| Nationwide Children’s Hospital | 73 |

| Emory University | 68 |

| Indiana University-Purdue University at Indianapolis | 65 |

| University of California, San Diego | 64 |

| University of Colorado, Denver | 61 |

| Stanford University | 58 |

| University of Pittsburgh | 57 |

| Vanderbilt University | 46 |

| University of Minnesota | 45 |

| Johns Hopkins University | 44 |

NOTE: The top 15 institutions that accounted for 1,561 (63 percent) of the 2,471 individual Pediatric R01 awards from January 2012 to May 17, 2017.

SOURCE: Good et al., 2018b. Reproduced with permission from JAMA Pediatrics. Copyright ©2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Trans-NIH Pediatric Research Consortium