The Future Pediatric Subspecialty Physician Workforce: Meeting the Needs of Infants, Children, and Adolescents (2023)

Chapter: 7 Innovations at the Pediatric PrimarySpecialty Care Interface

7

Innovations at the Pediatric Primary–Specialty Care Interface

The nation’s primary care workforce for children comprises many clinicians, including general primary care pediatricians, family medicine physicians, general internists (particularly in rural areas and for adolescents and young adults), and advanced practice providers (e.g., nurse practitioners [NPs], and physician assistants). There is also an extended team of health care professionals that work with primary care clinicians. Depending on needs, these professionals can include professionals such as behavioral health specialists, social workers, community health workers, and care coordinators (NASEM, 2021b). (See Chapter 4 for a discussion of the overall pediatric workforce.) The pediatric medical home includes pediatric clinicians (known to the child and family) who deliver or direct primary medical care that is “accessible, continuous, comprehensive, patient- and family-centered, coordinated, compassionate, and culturally effective” while a pediatric medical neighborhood includes “pediatric medical subspecialists, surgical specialists, mental and behavioral health specialists, and other [community partners] who work collaboratively with the pediatric medical home” (Price et al., 2020 pg. 2).

Ideally, general primary care clinicians and pediatric subspecialty physicians work collaboratively at the interface of primary and specialty care to provide the full spectrum of care for children with more complicated and unusual acute and chronic disorders. Most health issues for children are initially addressed in pediatric primary care, which acts as the site of first contact for the full range of a child’s new health needs and the site of comprehensive care for routine care, preventive services, and most disorders. Primary care clinicians coordinate referrals to specialists or subspecialists

within a patient’s medical neighborhood (Kirschner and Greenlee, 2010; Medical Home Initiatives for Children with Special Needs Project Advisory Committee, 2002; NASEM, 2021b; Starfield, 1998). This chapter examines the interaction of primary care and pediatric subspecialty care with a focus on the efficient use of both primary care and subspecialty care clinicians and innovative models at the interface of primary and specialty care so as to ensure the delivery of high-quality subspecialty care.

COLLABORATION AND COORDINATION BETWEEN PEDIATRIC PRIMARY AND SPECIALTY CARE

General primary care and subspecialty pediatric clinicians often work closely together to deliver comprehensive care for children with and without complex medical needs, along with other health care providers and community partners. Collaboration and coordination among all members of the health care team is a component of high-quality care (Eichner et al., 2012; Huang and Rosenthal, 2014; Lax et al., 2021). The 2001 Institute of Medicine report Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century emphasized the importance of an interprofessional team to meet the needs of patients with increasingly complex health care needs (IOM, 2001). Team-based care has been defined as:

the provision of health services to individuals, families, and/or their communities by at least two health providers who work collaboratively with patients and their caregivers—to the extent preferred by each patient—to accomplish shared goals within and across settings to achieve coordinated, high-quality care. (Mitchell et al., 2012)

Team-based care has been associated with higher quality of care, higher patient satisfaction, lower use, and reduced clinician burnout (Meyers et al., 2019; NASEM, 2021b; Pany et al., 2021; Reiss-Brennan et al., 2016; Will et al., 2019; Willard-Grace et al., 2014). In children specifically, research reveals the impact of team-based care on health maintenance, prevention of disease, acute illness management, and chronic disease management (Burkhart et al., 2020; Katkin et al., 2017; McLeigh et al., 2022; Reiss-Brennan et al., 2016). Team-based care was included among recommendations in the 2021 report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (National Academies) on high-quality primary care (NASEM, 2021b). For example, one study showed that among chronically ill children, team-based care resulted in fewer hospitalizations, emergency department visits, and urgent care visits (Meyers et al., 2019). A few studies of children and adolescents have evaluated co-management of conditions between primary and subspecialty care with generally positive results (Richardson et

al., 2009; Van Cleave et al., 2018). A meta-analysis of integrated primary care–behavioral health models for children and adolescents demonstrated superior outcomes for the integrated care model when compared with conventional care, and collaborative care models with a team-based approach that included primary care clinicians, care managers, and mental health specialists showed the strongest effects (Asarnow et al., 2015; NASEM, 2021b). See Box 7-1 for clinician perspectives on team-based care among pediatric primary and specialty care clinicians.

However, current payment models for care generally do not reward aspects of primary care–subspecialty collaboration, creating a disincentive for further evaluation and implementation of collaborative models (Kuo et al., 2022; Landon, 2014; Price et al., 2020). In August 2022, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) released guidance on a new option for states to cover an optional health home plan benefit in their Medicaid programs for children with medically complex conditions (CMS, 2022c). This new option enables states to design coordinated care systems for Medicaid-eligible children with chronic or rare conditions and allows flexibility with respect to certain Medicaid provisions such as statewideness1

___________________

1 Statewideness refers to a requirement that the managed care program must be operational statewide.

and, notably, payment methodology. For example, states can reimburse designated providers (including providing higher payment to compensate for coordination time) or can reimburse teams. The federal government provides enhanced matching funds for the first 2 years of such programs to support their implementation.

Care Plans

Evidence from behavioral health integration shows that shared plans of care can significantly enhance the quality of care, prevent duplication of services, and reduce risk of adverse events (Collins et al., 2010). However, fewer than half of pediatric primary care clinicians in one study reported that patient care plans were integrated with pediatric medical subspecialists (Stille et al., 2006). Furthermore, pediatric primary care clinicians and subspecialists who did not consistently receive communications were significantly more likely to report that their ability to provide high-quality care was compromised (Stille et al., 2006). This speaks to a need for better coordination to facilitate subspecialty care for the elements of care that only a subspecialist can perform while delegating some aspects of care for a condition to a primary care clinician. For example, pediatric subspecialty care has become more sophisticated in the use of therapeutics for chronic conditions that require expertise and facilities not typically available to primary care clinicians. The use of biologic pharmaceuticals for immune-mediated conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease, juvenile inflammatory arthritis, and even severe eczema often requires access to an infusion center for administration and carries the risk of serious side effects that must be closely monitored.

Patients and Families

When children require care from multiple subspecialists and/or require multiple other health care services, coordination of that care is time-consuming but necessary to avoid duplication of and gaps in needed services. However, such coordination is frequently absent or fragmented, leaving parents as the main link between clinicians in different organizations (Stille et al., 2007). These themes were highlighted by Ileana Barron, parent of a child who receives pediatric subspecialty care, during the committee’s first webinar on patient and family perspectives.2

___________________

2 The webinar recording can be accessed at https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/07-19-2022/the-pediatric-subspecialty-workforce-and-its-impact-on-child-health-and-well-being-webinar-1.

Along this journey, my family has seen the ways the system makes getting care easier, but we’ve also seen the gaps that make specialty care complicated and frustrating. And for those issues that complicate care, we can put coordination of care at the top of the list…First, unless the subspecialists share a combined clinic, communication is often difficult, even within the same hospital system. And in many cases, it relies on individual initiatives to maintain those connections. When we think that communication will be easy when clinicians have access to the same medical record system, but it often isn’t, it is essential that the subspecialists talk to each other and develop a shared care plan. But doing so is often difficult, and we have found ourselves being passed back and forth between specialists many times. The second problem in coordinating care is a lack of communication effort between subspecialists and primary care clinicians. Pediatricians are rarely well informed about what subspecialists are doing. They’re rarely fully included in the care plan, and parents like me and my husband often have to be the ones keeping the pediatrician up to date with the care plan. Our complicated son should be able to go to the pediatrician instead of the top specialist to handle acute exacerbations of his chronic illnesses. And although some hospitals have created specific complex care clinics that are meant to deal with these issues, the benefits of these clinics are limited to current patients of these large hospitals. Children like my son will continue getting colds that potentially become pneumonias, and gastrointestinal illnesses that would require a specific and unique care plan of care. So having a pediatrician who is part of the team and feels comfortable treating these complex children in those situations will keep families like mine from having to go to the ED [emergency department] or having to reach out to the subspecialist for one of those impossible to get sick child appointments…. For the things that make the system work more efficiently…[having] other professionals, health professionals support the specialist practices, having NPs or PAs [physician assistants] that are trained in the subspecialty field, is very important.

This sentiment was reiterated by a clinician who responded to the committee’s call for perspectives:

I find families either do not access what is needed or end up duplicating evaluations/services or spend time accessing unnecessary resources because of poor communication and fragmented care (need to see a different professional for every problem even though one clinician might be able to address) which increases the stress on families and cost to the health care system.

—Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrician, Wyckoff, NJ

Care Coordination during Transitions from Pediatric to Adult Care

As discussed in Chapter 2, the transition from pediatric to adult care can be difficult. One review of 29 studies that focused on adolescents and young adults with chronic health conditions concluded that shared models of care and communication among the primary care clinician, the adolescent/young adult, and the pediatric subspecialist were associated with positive outcomes during transition (Schraeder et al., 2022). Without adequate support during this transition, adolescents and young adults with chronic illnesses face an increased risk of adverse outcomes, including medical complications, decreased treatment adherence, increased emergency department use and hospitalization, and increased health care costs (McManus et al., 2020; White et al., 2018).

Transitions of care require support, planning, and intentional actions among multiple clinicians to create a defined, purposeful transition from pediatric to adult care (Castillo and Kitsos, 2017; Got Transition, 2022). Registered nurses are well suited to act as the liaison between the pediatric and adult practices. Specifically, registered nurses can help with the management of referral documents, quality improvement processes to ensure effective communication among clinicians, and in monitoring the transition overall (Betz, 2017; Varty et al., 2020). During one of the committee’s information-gathering sessions, Christian Lawson discussed his transition from pediatric to adult care:

[The] transition from pediatrics to adult GI was a little bit of a challenge…eventually when I did transition, we were able to form this partnership between my physician and my specialist, so now they kind of work hand in hand with trying to make sure that the records are up to date on both sides…it works well, primarily if it’s kind of in the same network or same area where the specialist might be.3

Adult subspecialists have found the transition of care for children with special health care needs to be more complex compared with assuming care of adult chronic care patients (Kobussen et al., 2021). Specifically, adult subspecialists found challenges that include increased time and resource burdens; the management of the expectations of patients and families; navigation of the discrepancies in goals of care; the complexity of coordination among services; and a need for increased efforts in coordinating discharge from the hospital (Kobussen et al., 2021). To facilitate successful transitions of care for pediatric patients, clinicians who provide care for adults have

___________________

3 The webinar recording can be accessed at https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/07-19-2022/the-pediatric-subspecialty-workforce-and-its-impact-on-child-health-and-well-being-webinar-1.

expressed a desire for improved infrastructure (e.g., links to community resources, consultation support when needed) and education and training about specific diseases as well as the physical and behavioral stages of adolescent development (White et al., 2016). Given gaps in physician training around transitions of care and extensive role of care coordination associated with transitions of care, there is a vital role for interprofessional teams (particularly the inclusion of registered nurses and NPs) in supporting these transitions (Betz, 2017; Castillo and Kitsos, 2017; Lestishock et al., 2018; Lestishock, 2020; NASEM, 2021a; Sharma et al., 2014).

CHALLENGES OF CONSULTATION, REFERRAL, AND CO-MANAGEMENT

Primary care clinicians often care for many patients with chronic conditions. For example, Nasir et al. (2018) found that more than half of pediatric patients in community clinics had at least one chronic problem, and 25 percent had at least two. Primary care clinicians generally refer to subspecialists when children: (1) have problems that are rare; (2) require a technical procedure; (3) need recommendations to support a specific diagnosis or treatment; (4) do not respond to conventional therapy; or (5) display signs and symptoms that could indicate the presence of a condition that is more severe than can be typically managed within primary care.

Referral Processes

Referral from primary care clinicians to subspecialists is a multistep process, and barriers can exist within these steps. During one of the committee’s information-gathering sessions, Kristin Ray, associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, presented on pediatric referral processes; much of the following section is based on this presentation.4 (See Chapter 2 for more information on demand for referrals.)

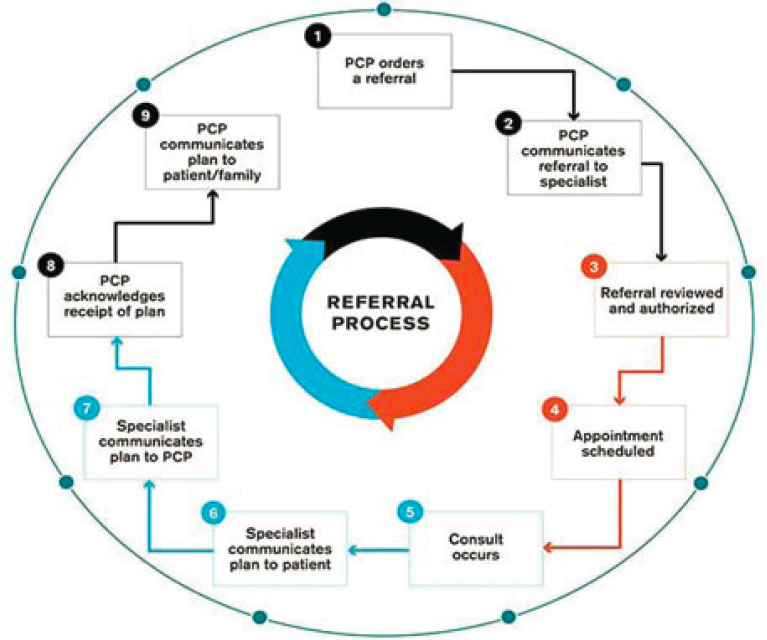

A 2017 report from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement provided insight into the steps that are required for optimal referral and the degree to which optimal closed-loop referrals involves multiple people (see Figure 7-1).

According to the report, primary care clinicians, specialists, patients, and schedulers are involved in nine overall steps, each of which can experience barriers that contribute to suboptimal access to pediatric subspecialty

___________________

4 The webinar recording can be accessed at https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/11-09-2022/the-pediatric-subspecialty-workforce-and-its-impact-on-child-health-and-well-being-webinar-4.

NOTE: Technical (hardware, software) factors are noted in blue; sociological factors (workflow, staff) are noted in orange; PCP = primary care provider

SOURCE: Institute for Healthcare Improvement and the National Patient Safety Foundation (2017). Reprinted with permission from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, ihi.org.

care. At the initial step of referral decision, primary care clinicians may be uncertain regarding whether to refer, where to refer, and the degree of work to be completed before referral. At the next step of preconsultative communication, information may not be sent, received, or reviewed. In appointment scheduling, there may be inadequate capacity for scheduling due to demand exceeding supply, leading to an inability to schedule or to long wait times. In addition, barriers are present internally to the scheduling process; long phone trees or unattended voice mailboxes can lead to unscheduled or suboptimally scheduled appointments. Within the consultative visit, there may be geographic or time barriers, language and literacy barriers, or other equity issues that interfere with an optimal visit. At the postconsultative communication step, there may be inadequate communication processes

among patients, specialists, and primary care clinicians that lead to confusion, inadequate care, or care redundancies.

Many referrals are never completed due to these barriers. A study of one year of referrals from primary care clinicians to medical and surgical subspecialists was found that only 51 percent of referrals resulted in a completed visit within 3 months of referral (Bohnhoff, 2019). Out of the remainder of referrals, a third were never scheduled, and an additional sixth were scheduled, but not attended. According to the 2020–2021 National Survey of Children’s Health,5 26 percent of families in need of subspecialty care encountered difficulty in obtaining specialty care (NSCH, n.d.).6 This percentage increased to 32 percent for families with a primary household language other than English, 32 percent for children receiving public insurance, and 40 percent for children who are uninsured, thereby contributing to inequities in access and use (NSCH, n.d.). (See Chapter 2 for more on the influences on children’s access to subspecialty care.)

Training for Consultation and Referral

Truly integrated care will require enhanced training in some areas, particularly subspecialty referral and appropriate consultation (Ray et al., 2016). The American Board of Pediatrics has identified “provide consultation to other health care providers caring for children” and “refer patients who require consultation” as essential, entrustable professional activities7 for graduating pediatric residents (ABP, 2023; Hamburger et al., 2015). However, among pediatric residents from 2015 to 2018, nearly one-third (31 percent) of graduating residents did not achieve “entrustment with unsupervised practice” for providing consultations and 18 percent did not achieve this benchmark for making referrals (Schumacher et al., 2020).

Training medical residents on how to interact effectively with consultants can improve collaborative care (Adekolujo et al., 2019). For example, Freed et al. (2020) suggested that focusing education on essential condition-specific management strategies for commonly referred oncology conditions enhances primary care management of these diagnoses. The Children’s National Hospital Syncope Education Project is an example of enhanced training for residents in the referral process wherein pediatric residents on

___________________

5 In the National Survey of Children’s Health, specialist doctors were defined as “doctors like surgeons, heart doctors, allergy doctors, skin doctors, and others who specialize in one area of health care” (NSCH, n.d.). See Indicator 4.5 for more information.

6 This percentage was calculated using Indicator 4.5a. The denominator of this measure is based on the response to the question which asks whether the child received a specialist care.

7 Entrustable professional activities for pediatrics are “observable, routine activities that a general pediatrician should be able to perform safely and effectively to meet the needs of their patients” (ABP, 2023).

rotation in cardiology completed a “workshop focusing on red-flag criteria for cardiology referral and practiced with standardized parents” (Stave et al., 2022). The project resulted in “significant improvements in self-efficacy and parents’ rating of their communication” (Stave et al., 2022, pg.2). When the curriculum was expanded to focus on advanced communication skills, Stave et al. (2022) found that residents’ communication skills improved immediately postintervention for subspecialty referral. The authors suggest that this curriculum can be broadened to include other patient scenarios.

Expansion of the Role of Primary Care

The appropriate scope of pediatric primary care has been debated in the United States for decades (Leslie et al., 2000; NASEM, 2021b). Recent trends in the expansion of the role of primary care include integration with behavioral health, specifically, and with community providers to address social and structural determinants of health more generally (AACAP, 2023; Arbour et al., 2021; CMS, 2022b; Gillespie et al., 2022). Collaboration and co-management with subspecialists are a natural fit with these trends; however, this expansion of scope has not been met with a concurrent expansion of resources (Price et al., 2020), making it difficult for most primary care clinicians to embrace co-management to the degree they might otherwise. See Box 7-2 for clinician perspectives on resource challenges at the primary–specialty care interface.

Expanding the scope of primary care clinicians is particularly relevant in rural areas. During one of the committee’s public webinars, Robert Hostoffer, clinical professor at the Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine at Athens, and associate professor at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland), provided his perspectives on rural pediatric scope of practice, stating: “[for rural pediatricians], their scope of practice is large…a lot of time is spent on things that they can’t get a hold of a subspecialist for. I think their scope of practice has expanded.”8

PROMISING PRIMARY–SPECIALTY CARE MODELS

Appropriate primary care management and referral to subspecialists are important factors that affect demand for subspecialty care. Many diagnoses for which patients are referred may be addressable to some extent in primary care, and many specialist-induced follow-up visits for a referred health problem could be done in primary care settings. Reserving care by primary

___________________

8 The webinar recording can be accessed at https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/09-06-2022/the-pediatric-subspecialty-workforce-and-its-impact-on-child-health-and-well-being-webinar-2.

care clinicians for pediatric patients with common chronic conditions, such as asthma, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and obesity, or preparing them to provide some part of the care they might otherwise refer to a subspecialist would allow subspecialists to focus on the children with more severe and/or complex care needs and the technical work that primary care cannot address. However, the data analyses in Chapter 3, as well as older studies (e.g., Forrest et al., 1999), provide evidence that many common diagnoses in medical subspecialists’ practices may be conditions or health problems that can and should be routinely managed in primary care settings, suggesting a potential inefficiency in the use of referrals to pediatric medical subspecialists. Factors needed to facilitate optimal management and referral include education and mutual dialogue between primary care and subspecialty pediatric clinicians; prereferral management and treatment guidelines; new models of care; and payment models that acknowledge the time requirements and value of collaboration (Children’s National, 2023; Cornell et al., 2015; Feyissa et al., 2015; Harahsheh et al., 2021; NASEM, 2021b; Rubin et al., 2014; Seattle Children’s, 2023).

To achieve seamless integration of primary care and subspecialty care, innovations in workforce, processes, technology, payment, and setting of

care are needed, with a consideration of equity within each of these elements. Several evidence-based models show promise to increase access to pediatric subspecialty care and support the judicious use of all members of interprofessional pediatric care teams. Viewed broadly as innovations in pediatric care delivery, provider education, and interprofessional care, the committee categorized each innovation into a typology and summarized their supporting evidence below. The typology consists of the following:

- Integrating primary care and subspecialty care;

- Using telemedicine and telehealth (broadly defined);

- Facilitating access through nursing; and

- Appropriately financing the primary–specialty care interface.

Integrating Primary Care and Subspecialty Care

Promising models that integrate primary care and subspecialty care include models for co-management and co-location of primary care clinicians and subspecialists, educational activities to encourage expanded primary care clinician scope of practice, and the determination of appropriate management and referral guidelines.

Models of Co-Management

Co-managed care is a type of team-based care that is planned, delivered, and evaluated by two or more clinicians (Fevissa et al., 2015). The pediatric subspecialist can have different levels of responsibility in the comanagement model. For example, the subspecialist could be a co-manager with shared care and share long-term management with a primary care clinician for a patient’s referred health problem, or the subspecialist could be a co-manager with principal care and assume total responsibility for the long-term management of a referred health problem, while the primary care clinician cares for all other health conditions and concerns (Forrest, 2009). In exceptional cases where a child has a condition primarily involving a single organ system that requires intensive management, such as sickle cell disease or cancer, it may be appropriate for the subspecialist to serve as the primary manager, either for the short term (e.g., with cancer) or longer term (e.g., with sickle cell disease) (Antonelli et al., 2005; Van Cleave et al., 2016). Outcomes of co-management models have found improved communication and decreased inpatient use (de Banate et al., 2019; Cady and Belew, 2017; Casey et al., 2011; Cohen et al., 2012; McClain et al., 2014). Importantly, when co-management is arranged, making sure that primary care clinicians, subspecialists, and families agree on the specifics of the arrangement is essential so that expectations from clinicians and families are met and access to subspecialty care is maximized. According to a survey

conducted on pediatricians and family practitioners in New Hampshire, there was a widespread endorsement of the co-management model, particularly for conditions that were seldom encountered (McClain et al., 2014).

Several models promote co-management within the context of available local and regional resources for local primary care clinicians and subspecialists at referral centers (Cooley et al., 2013; Crego et al., 2020; Feyissa et al., 2015; Rubin et al., 2014). The implementation of co-management models can enhance the ability of primary care clinicians to treat prevalent pediatric conditions in the medical home, while allocating subspecialty resources for more urgent or complex care. Feyissa et al. (2015) found that co-management significantly improved the likelihood of pediatric concussion patients receiving primary care follow-up. A similar co-management model has also been used to address mild to moderate depression and anxiety (Rubin et al., 2014).

Two NP-led co-management models, TeleFamilies (using an advanced practice registered nurse [APRN] coordinator embedded within an established medical home) and PRoSPer (using a registered nurse/social worker care coordinator team embedded within a specialty care system), were developed for children with medical complexity in Minnesota and funded by research grants (Cady et al., 2015). These models used a nurse to undertake care coordination between primary care providers, subspecialists, and families of children with medical complexity, serving as a “one-stop shop” for care coordination among multiple services. A study of the TeleFamilies model indicated that patients and families highly value relationships and access to single individuals in care coordination and the APRN’s extended scope of practice lessened the handoffs necessary during care coordination, resulting in a faster resolution time and decreased risk of interruptions or delays in care (Looman et al., 2015). The PRoSPer model’s success was contingent on building relationships with families and primary care partners, helping the specialty care coordination team to communicate questions, concerns, and education on care management (Cady et al., 2015; Cady and Belew, 2017).

Co-Location of Primary and Subspecialty Care

Co-location, where clinicians work together in the same physical space, is another potential element of integration (Richman et al., 2018). Co-location allows clinicians to more easily communicate and coordinate care and offers opportunities for “warm handoffs”9 between clinicians (Blount, 2003; Bonciani et al., 2018; Platt et al., 2018; Richman et al., 2018).

___________________

9 A warm handoff is “a handoff that is conducted in person, between two members of the health care team, in front of the patient (and family if present)” (AHRQ, 2023).

Integrated Behavioral Health and Primary Care

Most evidence around the effectiveness of co-location comes from integrated behavioral health care, where behavioral health and primary care are provided in the same location (Bower et al., 2001; National Council for Mental Wellbeing, 2021; SAMHSA, 2023; Yonek et al., 2020). Co-location of primary care and specialty behavioral health services is a new strategic priority of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to address the urgent need for improved access to behavioral health care (HHS, 2022). The model uses mental health clinicians (primarily child psychologists, psychology trainees, and master’s-level social workers, as well as child psychiatrists and psychiatry trainees) who provide services at the same site as primary care; the model is generally supported by primary care clinicians because onsite specialty mental health services help to overcome access barriers (Collins et al., 2010; Platt et al., 2018; Strosahl, 2005).

According to a scoping review, integrated care programs have been found to increase the likelihood of families attending an initial appointment, complying with recommended treatment, and receiving specialty mental health care when needed, as compared with referrals to usual specialty care (Platt et al., 2018). The review also suggested that having the integrated care provider co-employed in both the primary care and specialty settings facilitated referrals to specialty care when necessary (Briggs et al., 2012; Levy et al., 2017; Platt et al., 2018; Subotsky and Brown, 1990; Ward-Zimmerman and Cannata, 2012). Implementation of co-location models varied, with team-based models (including psychology, social work, and psychiatry) receiving higher rates of referrals to the behavioral health clinician compared with a sole co-located provider (Germán et al., 2017).

Generalist Embedded in Specialty Clinics (Reverse Co-Location)

Multidisciplinary clinics for complex or rare conditions located within academic medical centers often become the medical home for children with these conditions. In many cases, these clinics benefit from the presence of a general pediatrician who can work with families to address aspects of the conditions that may not be easily addressed by a single subspecialty (Simon et al., 2017). For example, a general pediatrician embedded within a clinic treating children with myelomeningocele may address preventive, developmental, educational, and community resource needs of children in the clinic, filling an important gap in their care while allowing subspecialists to focus on their area of strength. There is some evidence for this model in adult behavioral health, known as “reverse co-location,” where a primary care clinician is stationed part- or full-time in a mental health specialty setting to

monitor the physical health of patients (Collins et al., 2010) with evidence of decreased emergency department visits (Boardman, 2006).

A variation on this model involves a general pediatrician embedded in the same physical spaces with subspecialists, but without their direct involvement, to evaluate uncomplicated potential referrals and escalate them to subspecialty care as needed, also called “access clinics.” Matt Di Guglielmo, director of the Division of General Academic Pediatrics at Nemours Children’s Hospital, described the access clinics at Nemours Children’s Health in his presentation at one of the committee’s public webinars.10 Given that wait times for specific pediatric subspecialties ranged from weeks to months, Nemours developed access clinics to improve 5-day access for new pediatric patients by embedding a general pediatrician, assisted by a nurse navigator into subspecialty clinics (Di Guglielmo et al., 2013, 2016). This model was initially implemented in three clinics: ADHD, headache, and gastroenterology. The ADHD clinic was staffed by psychologists, and the headache and gastroenterology clinics were staffed by general pediatricians who were not formally trained in those subspecialties. The generalists were given additional, specific training (in an ongoing manner), and the clinics were in the same physical space as the relevant subspecialists, enabling real-time consultation. Complementary strategies included physician priority telephone lines that were available for clinicians to call in and speak to a subspecialist within 5 minutes, and having a number of slots in the subspecialist’s schedule that would only open several days prior to the appointment.

Initial barriers included the reluctance of some general pediatricians to refer to another general pediatrician, but positive experiences led to greater use of the clinics. The clinics were successful in reducing wait times for new patient appointments. In these early clinics, wait times for a new patient visit in gastroenterology decreased from an average of 25 days to 1 day; similarly, wait times for headache/ADHD decreased from an average of 77 days to 1 or 2 days. Some clinics were phased out and others have been added. Nemours currently has these types of clinics in a variety of other subspecialty areas and is experiencing similar reductions in wait times. For example, the wait for a new patient visit in dermatology is now 1 week (compared with 4 months previously) and 1 month for behavioral and developmental health care (compared to with months previously). Additionally, clinicians, patients, and families reported high levels of satisfaction.

___________________

10 The webinar recording can be accessed at https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/11-09-2022/the-pediatric-subspecialty-workforce-and-its-impact-on-child-health-and-well-being-webinar-4.

Subspecialist Office Hours within the Primary Care Practice

For relatively common conditions requiring some degree of subspecialty input but not fully integrated care, subspecialists may be available for limited hours (e.g., 1 day a week) within a primary care clinic. This model may be particularly helpful for children with difficulty accessing the specialty care system because of distance or transportation difficulties.

Educational Activities to Encourage Expanded Primary Care Clinician Scope of Practice

Extending primary care clinician capacity to manage conditions that are commonly referred to subspecialists can be valuable for patients and enhance primary care clinicians’ satisfaction. While the American Board of Pediatrics defines numerous areas in which pediatricians should generally be able to provide a complete consultation (e.g., common behavioral and developmental concerns, acute and chronic health conditions, and mental health conditions), there are also areas in which general pediatricians should usually seek additional consultation such as critical care issues; complex or serious mental health conditions (e.g., suicidal or homicidal behavior, mental health conditions not responding to usual therapies); and complex or rare health conditions requiring medical or surgical subspecialty expertise (ABP, 2021).

Multiple-provider primary care practices often support the development of concentrations among individual clinicians who become the practice’s expert in caring for patients with common conditions that have specialty care needs (Cohen et al., 2018). Examples include behavioral health, pulmonary medicine for children with asthma, and gastroenterology for children with abdominal pain. This approach may avoid low-level or unneeded referrals to pediatric subspecialists, though it may require clinicians to attend trainings (e.g., mini-fellowships ranging from a few days to a few months) or to engage in onsite subspecialist observation to gain needed knowledge and skills. Primary care clinicians who acquire this type of expertise may benefit from referrals to subspecialists for only the most complex cases, as there is acknowledgement of the primary care clinician’s capability to manage many conditions, increasing the perceived urgency of these subspecialist referrals (Canin and Wunsch, 2008). The REACH model for patient-centered mental health care in primary care, which supports clinicians in developing skills to diagnose and treat a spectrum of pediatric mental health conditions, is one example of how condition-focused education can expand the capacity of primary care to the most needed subspecialty care (Green et al., 2019; The REACH Institute, 2022). Ongoing education

on these conditions as part of maintenance of certification can ensure that clinicians’ knowledge evolves with dynamic subspecialty practice.

Referral and Management Guidelines

Even prior to a patient evaluation in subspecialty care, guidelines and recommendations for initial evaluation and management in the primary care setting reduce subspecialty demand by eliminating unnecessary referrals. For example, children who are seen in subspecialty care frequently lack complete or appropriate initial work-up and can face delays in care while awaiting results after the initial subspecialist visit (Ip et al., 2022). Vernacchio et al. (2012) suggested that frequently visited subspecialties and commonly referred diagnoses such as acne (Strauss et al., 2007), asthma (NHLBI, 2007), chronic abdominal pain (Di Lorenzo et al., 2005), and ADHD (AAP, 2000, 2001) should be targeted for enhanced primary care management. Referral guidelines include criteria for when and how to refer these types of conditions to subspecialists and can help reduce unnecessary referrals, thereby improving access (Cornell et al., 2015). Referral guidelines also support primary care clinicians in the ongoing management of patients who need and are awaiting subspecialty care, help to address discrepancies in opinion, and build buy-in and receptivity for subspecialty care by patients and families (Children’s National, 2023; Cornell et al., 2015; Kwok et al., 2018; Seattle Children’s, 2023). Referral guidelines that include communication about referral may also improve show rates because, historically, when there is less good communication, referrals are not completed (Zuckerman et al., 2011). See Box 7-3 for clinician perspectives on the need for guidance on subspecialty care referrals.

Primary care and subspecialty clinicians do not necessarily find all guidelines for every condition to be useful (Ip et al., 2022). As a result, involvement of representatives from both primary care and specialty care is a critical aspect of successful referral guideline development and dissemination. Active dissemination can be promoted by directing clinicians to relevant referral guidelines (Cornell et al., 2015). The use of technology-enabled referral support also improves the interface between primary care and specialty clinicians; electronic messaging between clinicians where there is a planned referral needs to include initial management and referral guidelines (Ray and Kahn, 2020). Clinical decision support tools may offer automated recommendations based on specialists’ practice patterns, further tailoring an initial work-up, and evaluation in primary care prior to specialist care (Ip et al., 2022).

Using Telemedicine and Telehealth

A variety of technological approaches can extend subspecialists’ reach and improve the primary–subspecialty care interface. The terms “telehealth” and “telemedicine” have been used interchangeably. However, according to the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology, “while telemedicine refers specifically to remote clinical services, telehealth can refer to remote non-clinical services, such as providing training, administrative meetings, and continuing medical education, in addition to clinical services” (ONC, 2019). Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, telehealth technologies were recognized as an important mechanism for increasing access to pediatric subspecialty care and reducing urban/rural disparities (Marcin et al., 2016; Ray et al., 2017).

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) endorses the use of telehealth as an essential strategy to reduce health care disparities, and many state Medicaid programs now cover this care model for pediatric care, with

coverage that rapidly expanded during the COVID-19 pandemic (Price et al., 2020; Rudich et al., 2022). However, challenges regarding the use of telehealth in providing pediatric care management persist, including the inability for patients to access broadband services in rural areas, limited access to smartphone technology, patients and families with limited English proficiency, privacy for patients in their homes with other family members present, licensing across state lines, reimbursement, and education and training barriers (Buchi et al., 2022; Curfman et al., 2021; Preminger, 2022). Additionally, the impact of increased telehealth use on the workforce depends on whether patients use telehealth as a substitute for in-person visits or as a way to see their clinician more often; it will also depend on whether increased use of telehealth affects provider productivity or the decision to enter fields with higher levels of telehealth use (IHS Markit Ltd., 2021). Patients and families that use telehealth value transparent and reliable scheduling, continuity with trusted providers, clear directions on telemedicine use, and preserving family choice regarding method of care delivery (Ray et al., 2017).

Different types of telehealth and telemedicine, such as live interactive patient visits, store-and-forward patient visits11 (also known as electronic visits, or e-visits), telementoring, and electronic consultations (e-consults), are distinct and synergistic in their ability to improve collaborative care (Giavina-Bianchi et al., 2020). For example, patients and subspecialists can connect in real-time through live, interactive patient visits or e-visits. E-visits are built robustly in teledermatology, in which patients can send pictures to a dermatologist and receive treatment advice in return (Faucon, 2022; Sud and Anjankar, 2022; Tensen et al., 2016). Live, interactive visits and e-visits can address geographic and time barriers that may limit attendance at scheduled visits (Olayiwola et al., 2019). Technology can also be used to connect primary care clinicians and subspecialists through telementoring that occurs in real-time or through asynchronous electronic consultations (e-consults).

e-Consults

Electronic consults (or e-consults) are defined as “directed communication between providers over a secure electronic medium that involves sharing of patient-specific information and discussing clarification or guidance regarding clinical care” and have been touted as a mechanism to improve access to subspecialty care, in addition to improved collaborations among clinicians. One Milbank report declared e-consults a “triple win for

___________________

11 Store-and-forward telehealth is a type of asynchronous telemedicine service that allows patients to submit clinical information for evaluation without an in-person visit.

patients, clinicians, and payers” (Thielke and King, 2020). Clinician-to-clinician e-consults have been successful when there is clinical uncertainty and concern for timely access to care (Kwok et al., 2018; Ray and Kahn, 2020). Effective use of these types of technologies assists the primary care clinicians in managing the family experience during referral along with expectations of subspecialty care (Ray et al., 2016; Ray and Kahn, 2020).

E-consults can help to deliver care and save costs through reduced subspecialist use and improved care coordination. A growing body of literature highlights e-consults’ contributions to reductions in wait times and improvements in patient satisfaction across multiple settings (Abu Libdeh et al., 2022; Bhanot et al., 2021; Patel et al., 2020; Porto et al., 2021; Vimalananda et al., 2020). Furthermore, e-consults can potentially address multiple barriers in the first half of the referral process by addressing uncertainties about referrals, facilitating preconsultative communication between primary care clinicians and specialists, and addressing the supply and demand imbalance by reducing the demand for in-person subspecialty visits. Some e-consult infrastructure systems pay specialists for their consultation, but they often do not pay primary care clinicians for their increased labor and care coordination (which would not be needed in traditional models if the subspecialist communicated directly with the patient) (Thompson et al., 2021; Vimalananda et al., 2015).

In his presentation to this committee during a public webinar, Alexander Li, deputy chief medical officer of L.A. Care, highlighted several challenges to the successful implementation of e-consults, including the need for reimbursement for both primary care clinicians and subspecialists, the time required to assist patients with the technology, and the lack of infrastructure in smaller practices.12 Resources and payment models are needed to remedy these challenges given that prior studies have found that e-consults (when combined with evidence-based care pathways) can allow more care to be delivered in primary care and therefore reduce demand on subspecialists and improve access (Porto et al., 2021).

In guidance issued in January 2023, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) clarified that interpersonal consultation services is “a distinct, coverable service in the Medicaid program and in the Children’s Health Insurance Program, for which payment can be made directly to the consulting provider” (CMS, 2023e). This policy superseded previous policy under which additional payment for the consulting provider went to the treating provider, who then passed on that reimbursement to the consulting provider. While CMS encourages states to base fees for consulting services

___________________

12 The webinar recording can be accessed at https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/11-09-2022/the-pediatric-subspecialty-workforce-and-its-impact-on-child-health-and-well-being-webinar-4.

off Medicare rates for the same services, it confirms that states hold flexibility in determining payment rates for consultation services. As of July 12, 2023, no states had approved state plan amendments to cover e-consult services under this rule.13 See later in this section for more on telehealth/telemedicine coverage.

The Coordinating Optimal Referral Experiences Model

In his presentation to this committee during a public webinar, Scott Shipman, CyncHealth Endowed Chair of Population Health at Creighton University, described the Coordinating Optimal Referral Experiences (CORE) Model.14 The CORE Model was developed for primary care in general, including pediatrics. In this model, primary care physicians determine whether to refer patients directly to a specialist or use an e-consult while continuing to manage that patient’s care. The primary care physician can share the information asynchronously so that the specialist can determine if the case is too complex for an e-consult and instead requires a traditional referral. The Project CORE Network began in 2014 when the Association of American Medical Colleges was awarded a Healthcare Innovation Award from the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation Center. Most of the initial sites expanded the model to their children’s hospitals and pediatric patients over time. Limited evaluations of the CORE model have demonstrated high levels of patient and provider satisfaction in adult care, as well as improvements in timely access to specialty expertise, and reductions over time in referral rates and volumes from primary care providers with above average use of eConsults, when compared to their peers (Ackerman et al., 2020; Deeds et al., 2019; Gilman et al., 2020). The degree to which this is generalizable to the use of eConsults for pediatric patients is unclear, though early trends from children’s hospitals are favorable. Providers overwhelmingly believed that the program affects patients positively, and 80 to 85 percent of primary care clinicians voluntarily used e-consults (CHA, 2021; McCulloch et al., 2023). By the third year of the project, 86 percent of e-consults were resolved without a subsequent specialist visit.

However, e-consult volumes, and the degree to which they replace referrals, differs by specialty. Generally, specialties that place more emphasis on laboratory results and the non-procedural specialties tend to have higher levels of penetration for e-consults, reflected in both child and adult data.

___________________

13 The most updated list of Medicaid State Plan Amendments can be found at https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/medicaid-state-plan-amendments/index.html (accessed July 12, 2023).

14 The webinar recording can be accessed at https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/11-09-2022/the-pediatric-subspecialty-workforce-and-its-impact-on-child-health-and-well-being-webinar-4.

Non-procedural specialties, particularly those to whom referral are commonly triggered by abnormal lab or imaging results, have been shown to have the highest use of e-consults in both adult and pediatric populations.15 The effectiveness of e-consults in changing care depends not only on the penetration of using e-consults in place of referrals, but also the volume of consultations.

Using e-Consults for Precision Scheduling

In his presentation to this committee during a public webinar, Hal Yee Jr., chief deputy director, Clinical Affairs and chief medical officer, Los Angeles County Department of Health Services, highlighted using e-consults for precision scheduling.16 Precision scheduling is an attempt to move toward a “right time” model of care. It is defined as scheduling an appointment within the time frame recommended after dialogue between the primary care clinician and specialist about the patient’s needs and available specialist access after using an e-consult to define the situation. The “right time” should not be too late, but also not too early. Precision scheduling aims to optimize use of specialty capacity in both face-to-face and real-time video. Patients who are scheduled “on-time” are within the precision scheduling definition; “late” scheduling (not within the precision scheduling time) may occur when patients are not available for a visit, lack transportation, or have personal preferences.

Telephone Consultation

A “lower tech” approach to improve access to real-time consultations for primary care clinicians is the use of a standing telephone call line. A key example is the availability of behavioral health consultation with child psychiatrists and mental health specialists. The Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Project (MCPAP), now replicated in most states, was created in the mid-2000s, and includes initial consultation via a hotline, outpatient mental health consultation within 2 weeks if clinically indicated, care coordination, and primary care clinician continuing education (Sarvet et al., 2010; Connor et al., 2006). The consultation team includes a care coordinator, psychotherapist, and child psychiatrist. The care coordinator provides information about community mental health services for children and routes clinical questions to the available child psychiatrist or psychotherapist. If

___________________

15 Data provided by Scott Shipman in his presentation to the committee, November 9, 2022.

16 The webinar recording can be accessed at https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/11-09-2022/the-pediatric-subspecialty-workforce-and-its-impact-on-child-health-and-well-being-webinar-4.

the question is related to differential diagnosis or medication, the call is directly sent to the child psychiatrist. The overarching goal is to provide consultation while the patient is still with the primary care clinician.

Statewide implementation was made possible through funding included in the Massachusetts state budget to cover all operational expenses (Sarvet et al., 2010; Van Cleave et al., 2018). One analysis of calls from primary care clinicians to MCPAP from October 1, 2010, to July 31, 2011, showed that reasons for use among frequent users included timely and tailored guidance to the child, the ability to arrange therapy referrals, and the ability to provide a plan at point of care for families, including keeping mental health care in their primary care setting, when preferred (Van Cleave et al., 2018). Findings from other states also suggest that statewide implementation is feasible (Cotton et al., 2021; Hilt et al., 2013; Sullivan et al., 2021). According to Stein et al. (2019), “children from states with statewide child psychiatric telephone access programs are significantly more likely to receive mental health services than children residing in states without such programs.”

As programs expand to other states, however, there are concerns about sustainability and that traditional insurance mechanisms are not designed to reimburse child psychiatrists’ time spent on pediatrician consultation, indicating the need for state or other sources of funding (Sullivan et al., 2021). Nevertheless, variations of the MCPAP model have been replicated in 38 states, the District of Columbia, and British Columbia. In October 2014, the National Network of Child Psychiatry Access Programs, Inc., a Massachusetts nonprofit organization, was created to provide technical assistance to support the development of the model in other states (NNCPAP, 2022). Future research is needed to examine use at the child and clinician levels by sociodemographic characteristics and clinical characteristics (e.g., type of psychiatric diagnosis, clinical severity, psychosocial complexity); use by type of intervention component; the extent to which real-time consultation (while the patient is in a primary care setting) is met; and the relationships among use of the intervention, provision of evidence-based mental health care, and clinical outcomes.

Telementoring

An important example of remote integration of primary and subspecialty care is Project Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO). The 2021 National Academies report on high-quality care described this example of telemonitoring:

Project ECHO connects governments, academic medical centers, nongovernmental organizations, and centers of excellence around the world to

“telementor” clinicians for the purpose of training, enabling collaborative problem solving and co-management of cases, and ultimately improving quality of care in underserved communities (UNM, 2022a). Originally designed by the University of New Mexico for the treatment of hepatitis C, today Project ECHO operates in 45 countries (UNM, 2022b) and has been used to disseminate clinical training on cancer screening, addiction management, perinatal care, COVID-19 treatment, and many other primary care domains (Archbald-Pannone et al., 2020; Coulson and Galvin, 2020; Francis et al., 2020; Komaromy et al., 2016; Nethan et al., 2020). With its hub-and-spoke model, Project ECHO enables regular, bidirectional knowledge sharing and collaboration between geographically isolated care team members; fostering new local partnerships; or facilitating the development of new services where they were previously unavailable or insufficient. Project ECHO has been successful, with outcomes including increased knowledge and self-efficacy among clinicians, decreased feelings of professional isolation, increased safety and improved treatment outcomes for patients, and greater ability to enact practice transformation projects (McDonnell et al., 2020). (NASEM, 2021b)

Many pediatric programs have adopted the ECHO model. ECHO has been found to be both feasible and acceptable to conduct virtual education of interprofessional health care providers in managing children with medical complexity. Indeed, AAP has created and launched more than 100 ECHO programs in over 20 topics, including childhood anxiety, childhood obesity, and spina bifida (AAP, 2023), and most recently, pain management (Lalloo et al., 2023). AAP has acted as an ECHO Superhub to train organizations in the model and to support peer and expert learning communities. Recently, the ECHO model has helped support pediatricians in learning about COVID-19 (Bernstein et al., 2022).

Telehealth Coverage

The 2020 AAP Policy Statement on Financing the Medical Home emphasizes the importance of paying for telehealth, urging that:

Appropriate non–face-to-face encounters via telephone and video and those on digital platforms, such as the Internet, e-mail, electronic health record portals, and other secure encrypted communication, that provide meaningful care should be paid for adequately to facilitate optimal function of the medical home and to improve patient and family satisfaction. These interactions may occur between the patient and family and the medical home or between the medical home and specialty care providers (Price et al., 2020).

This position has been reaffirmed in other policy statements (Brown et al., 2021; Carlson et al., 2022; Curfman et al., 2021).

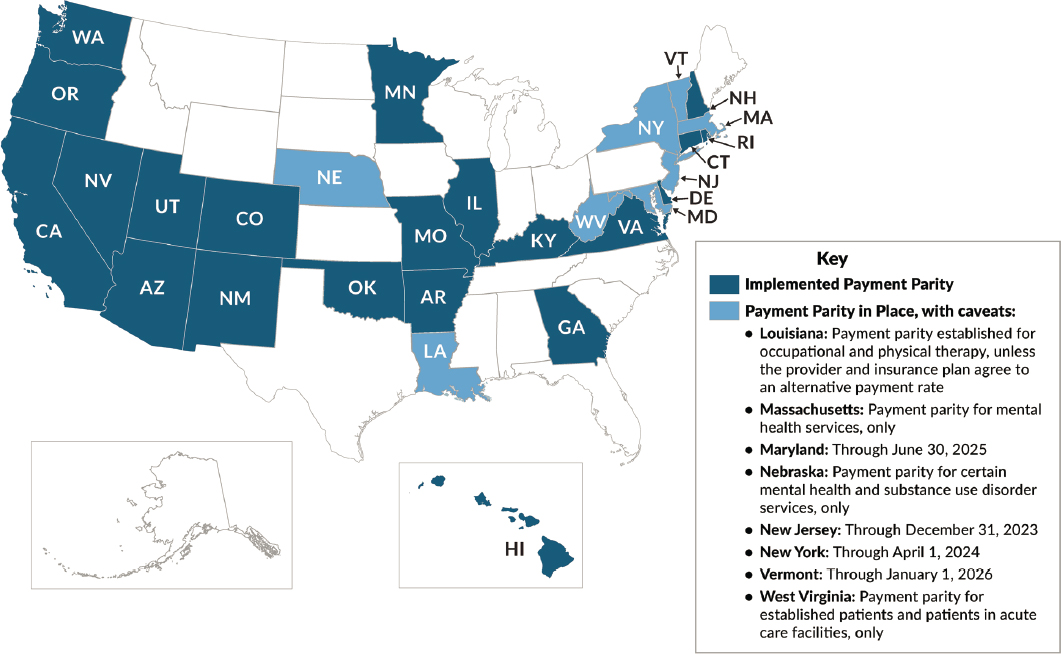

Many commercial health plans broadened coverage for telehealth in response to COVID-19 and cover at least some form of telehealth service. As of May 2023, 43 states, the District of Columbia, and the Virgin Islands have a private payer law that addresses telehealth reimbursement, with 24 states requiring payment parity for at least one specialty (CCHP, 2023a; HHS, 2023). States have flexibility to cover telehealth services under Medicaid. Unless specifically required by regulation or policy, states can cover such services without submitting a state plan amendment if they reimburse telehealth in the same way and amount as face-to-face services. If states want to reimburse telehealth services differently from face to face, they must submit and receive approval for a state plan amendment if that is not already specified in the state plan (CMS, 2023b). States also have flexibility in setting payment policy for telehealth services in Medicaid, though reimbursement “must satisfy federal requirements of efficiency, economy, and quality of care” (CMS, 2023a). Even before the pandemic, most states covered telehealth for at least some services (CCHP, 2020; Chu et al., 2021).

Most states require managed care organizations that serve Medicaid beneficiaries to follow state fee-for-service telehealth rules, and some allow managed care organizations to adopt more expansive policies than the state fee-for-service requirements. According to research conducted between January and March 2023, all 50 states and Washington, DC, provide reimbursement for some form of live video in Medicaid fee-for-service,17 28 states allow store-and-forward telehealth services in Medicaid,18 34 allow remote patient monitoring,19 and 36 states and Washington, DC, reimburse for audio-only telephone in some capacity (CCHP, 2023b). Most states also allowed a patient’s home (versus provider office) to serve as the originating site and covered other sites such as schools (CCHP, 2023b; Chu et al., 2021). According to Hinton et al. (2022b): “In 2021, all responding states indicated that they ensured payment parity between telehealth and in-person delivery of [fee-for service] services (as of July 1, 2021), which may have been under emergency policy; most states reported no changes in FY2022 or FY2023 to parity requirements. A small number of states reported that in FY2022 or FY2023 they established telehealth payment parity on a permanent basis.” As of June 2023, 21 states have implemented payment parity

___________________

17 Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands do not indicate reimbursement for live video in their Medicaid programs (CCHP, 2023a).

18 Three states (Illinois, North Carolina, and Ohio) solely reimburse store-and-forward as a part of Communications Technology Based Services (CTBS), which is limited to specific codes and reimbursement amounts (CCHP, 2023a).

19 Four of the states reimburse only for specific remote patient-monitoring CTBS codes, including California, Massachusetts, Hawaii, and West Virginia (CCHP, 2023a).

policies, 8 states have these policies with certain caveats, and 21 states have no payment parity (Augenstein and Marks Smith, 2023) (see Figure 7-2). Moreover, an important barrier to primary care-subspecialty collaboration in care is that payment for a telehealth visit is only made to one provider, rendering joint primary care-subspecialty visits infeasible. See later in this section for more on telehealth coverage during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Cross-State Telehealth Policy

State licensing issues arise when the patient and the provider are in different states. States have the authority to regulate the practice of physicians and other health care professionals within their state boundary. Because telehealth generally takes place at the patient’s home and not in the clinical setting, most states require that out-of-state providers be licensed in the state of the patient’s residence (Curfman et al, 2021). States may pay for Medicaid services provided to a beneficiary who is out of state under certain circumstances, including emergencies, services being more readily available in another state, or if it is general practice for beneficiaries in a locality to use medical resources in another state (42 CFR § 431.52). However, states vary in their policies, and there may be substantial administrative burden in accessing out-of-state providers (GAO 2019; MACPAC, 2020; Manetto et al., 2020). (See Chapter 2 for more information on out-of-state access barriers for in-person visits.) In October 2021, CMS issued guidance to states on care provided by out-of-state providers to children with medical complexity who are covered by Medicaid (CMS, 2021). The guidance included best practices for facilitating care from out-of-state providers, including (among others) coverage of telehealth services from out-of-state providers and payment to support services provided to out-of-state providers. See later in this section for more on cross-state licensing rules during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Interstate Medical Licensure Compact is an “agreement among participating U.S. states to work together to significantly streamline the licensing process for physicians who want to practice in multiple states. It offers a voluntary, expedited pathway to licensure for physicians who qualify” (IMLCC, 2022). The expansion of this compact could help to break down regulatory barriers to accessing subspecialty care for children in states with few pediatric subspecialists via telehealth.

Telehealth during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Patients’ reluctance to visit traditional health care settings early in the COVID-19 pandemic prompted health care systems to rapidly adopt telehealth for clinical care and for patients to engage providers via telehealth

SOURCE: Adapted from Augenstein and Marks Smith, 2023. Reprinted with permission from Manatt, Phelps & Phillips, LLP.

modalities at an accelerated rate. The early stages of the pandemic were associated with a major and very rapid shift from in-person appointments to telehealth encounters (Curfman et al., 2021). One study that examined telehealth use among patients requiring pediatric subspecialty management before and after the COVID-19 pandemic at a single academic health system found that the nature and scale of pandemic effects were complex and varied by pediatric subspecialty type, social demographics, and established patient status (Cahan et al., 2022). Consistent with other studies, established patients were more likely to complete telehealth appointments and newer patients were less likely to use the technology (Cahan et al., 2022; Nguyen et al., 2022). While in-person office visits declined for all subspecialties in 2020, the completion of telehealth visits was lower in pulmonology, oncology, and cardiology compared with endocrinology and neurology. These patterns may correspond with different subspecialty practice requirements, such as the need for a physical exam or imaging study (Cahan et al., 2022; Ray et al., 2015).

During the pandemic, states enacted a range of modifications to their Medicaid telehealth policies to expand access to and use of these services (Augenstein and Marks Smith, 2023; Cahan et al., 2022). These changes included waiving restrictions on distant and originating sites, modalities, and provider–patient relationships as well as issuing guidance focused on expanded telehealth access for specific services. For example, at least 13 states issued guidance for telehealth well-child and early and periodic screening, diagnostic, and treatment visits during the pandemic (AAP, 2021). Now that the infrastructure for telehealth practice is in place in many settings and patients have familiarity with remote clinical services, much care will likely continue to be delivered via telehealth, subject to continued favorable regulatory and reimbursement policies. While all states implemented Section 1135 waivers to allow out-of-state providers with equivalent licensing in another state to provide care to Medicaid enrollees during the pandemic (Guth and Hinton, 2020), many states have let those waivers lapse, though this varies by state (CCHP, 2023c). For example, Arizona allows out-of-state licensed health care providers without registration for certain criteria with no expiration date; Colorado allows occasional out-of-state provider telehealth services; Michigan and Minnesota allow out-of-state ability with no exception; and New Mexico can do so with registration (FSMB, 2023; University of Chicago, 2022).

Facilitating Access through Nursing

Since the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA), greater emphasis has been placed on team care and optimization of each team member’s contribution to care and care outcomes. The report Assessing

Progress on the Institute of Medicine Report The Future of Nursing noted, “in new collaborative models of practice, it is imperative that all health professionals practice to the full extent of their education and training to optimize the efficiency and quality of services for patients” (IOM, 2016, pg. 48). Subsequent National Academies reports reinforce the necessity of the health care team, with each member working to their fullest capabilities as well as identifying models of care that have potential application for improving pediatric care delivery (NASEM, 2021a,b). Nurses in both primary and subspecialty care settings can assume responsibilities that allow them to increase the availability of subspecialty care clinicians to meet the most critical or complex pediatric health care needs.

The Role of Nurse Practitioners

Models of care that include NPs often result from workforce needs and are informed by state regulatory structures. In common models, NPs have roles as (1) an adjunct to a resident or fellow, (2) a substitute for residents, (3) a supplement in an attending physician-only model, and/or (4) an independent clinician in a free-standing practice (Gigli et al., 2021; Wall et al., 2014; Winter et al., 2021). Pediatric NPs increase access to care for vulnerable populations, including children who have chronic health care needs, who live in rural and underserved areas, or are from low-income families (Buerhaus, 2018; Martyn et al., 2013). Furthermore, NPs are poised to improve individual- and population-level health inequities through their care delivery and partnership with communities (NASEM, 2021a). Additionally, initial studies of advanced practice providers as primary care clinicians for patients with complex care needs have found no increase in use and costs (Morgan et al., 2019). This sentiment was reiterated by a clinician who responded to the committee’s call for perspectives:

One way to increase the availability of subspecialty [care] for patients is to increase the use of pediatric nurse practitioners. In our area almost all pediatric subspecialties employ pediatric nurse practitioners. A significant number of my graduates elect to take positions in subspecialties. Most who make that choice stay in that subspecialty and are experts in the area.

– Pediatric nurse practitioner, Cleveland, OH

Despite the opportunities for NPs to increase access to high-quality pediatric care, barriers exist that limit their practice. One example is state-based, scope-of-practice regulations, namely state laws that delineate the amount of physician supervision or collaboration an NP must have to practice in a state. Currently, 27 states and the District of Columbia allow NPs

TABLE 7-1 Specific Exemplars of Implementation of Nurse-Led Care Responsibilities

| Patient Population | Care Setting | Nurse-Led Care Responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

| Children with obesity | Primary care | Education, health promotion and facilitation of social determinants of heatlh needs (Cheng et al., 2021); intervention delivery (Seburg et al., 2015) |

| Adolescents with complex health needs (e.g., spina bifida, type 1 diabetes mellitus) | Ambulatory care | Support to teach self-management of chronic disease, facilitate transitions of care to adult clinicians, care coordination (Campbell et al., 2016) |

| Monitor the acquisition of self-management knowledge and skills, including core self-management skills (e.g., knowledge of spina bifida, bladder management, skin care) and peripheral self-management skills (e.g., emergency resources in the community, medication refills, and equipment maintenance and replacement) (Betz et al., 2016) | ||

| Transition to adult care | Care coordination; building and maintaining trust with families of young people as they transition into adult services (O’Connell et al., 2019) | |

| Children in need of referral to subspecialty care | Primary care/outpatient | Triaging of patient referrals (Hong et al., 2015) |

| Children discharged from hospital after acute-care stay | Acute to primary care transition | Nurse home visits to provide education and health promotion interventions (Pickler et al., 2016); nurse-led telephone counseling intervention to provide pain management education, symptom management, and reduced readmissions (Özalp et al., 2016) |

| Children discharged from hospital | Acute care | Discharge planning, education, and referral for outpatient services (Breneol et al., 2018; Khair and Chaplin, 2017) |

full practice authority to “evaluate patients; diagnose, order, and interpret diagnostic tests; and initiate and manage treatments, including prescribing medications and controlled substances, under the exclusive licensure authority of the state board of nursing” (AANP, 2022). The remaining states impose requirements for collaborative or supervisory practice that are associated with smaller NP workforces, lower ability for patients to access care, and no evidence of improved care quality (Buerhaus, 2018; Kuo et al., 2013; Reagan and Salsberry, 2013). Within individual provider practices, hospitals, and health systems, NPs must also be granted

privileges to practice. There is growing evidence that institutions restrict NP practice through the privileging process, even within states that allow full practice authority, without evidence to demonstrate these institutional restrictions improve safety or quality (Bowman et al., 2022; Freund et al., 2015; Pittman et al., 2020). Additionally, within interprofessional teams in all practice settings, local practices create a culture that contributes to NPs’ work environment. The work environment includes (1) professional visibility, (2) NP–administration relations, (3) NP–physician relations, and (4) independent practice and support (Poghosyan et al., 2013b). The NP work environment contributes to patient and organizational outcomes, and lower quality NP work environments restrict NP practice and limit patient access to NP-provided care (Frogner et al., 2020; Poghosyan and Aiken, 2015; Poghosyan et al., 2013a, 2015; Scanlon et al., 2018). Furthermore, NPs are paid less than physicians for providing the same care. Medicare reimburses NPs at 85 percent of the physician rate, and private payers also pay NPs less than physicians (CMS, 2022a). These variations and limitations hamper NPs’ ability to contribute to high-quality, cost-effective pediatric care delivery (NASEM, 2021a). Elimination of unnecessary restrictions to NP practice can increase the types and amount of high-quality health care services that can be provided by NPs to those with complex health and social needs, thereby improving access to care and health equity (NASEM, 2021a).

Financing Innovations to Support Primary–Specialty Care Collaboration

Payment in pediatrics traditionally has been made on a fee-for-service basis, in which providers are paid for each specific service provided. Starting several decades ago, payers began moving to risk-based payment models (i.e., capitation payments) in which providers receive a set amount per month to care for patients on their panel. Often capitated payments were made to primary care providers, with specialists continuing to be paid on a fee-for-service basis (Alguire, 2023; Berenson et al., 2016; NASEM, 2021b; Volpp et al., 2018). These models created incentives for primary care to refer cases and sometimes hindered collaborative care. In some cases, multispecialty groups that combined primary care and specialty care jointly entered risk contracts, creating incentives for joint, efficient patient management, but these arrangements did not account for most patient care and often did not include pediatric care (Mechanic and Zinner, 2016). There is some evidence that children in capitated plans have greater use of urgent care and well-child and acute care delivered by the primary care provider, with lower odds of visits to emergency departments and specialty care (Canares et al., 2020).

In more recent years, payers have explored value-based payment (VBP) models, which generally tie payment to quality or health outcome (and sometimes cost or efficiency) goals (MACPAC, 2023). VBPs range from bonus systems tied to performance for an individual provider to payment at a population level. Within Medicaid, states have been using VBP in a variety of forms, including population-based payment models (CMS, 2020; Houston and Brykman, 2022); however, while children may be included in VBP models, most of these models are not specifically designed to serve pediatric populations (Bachman et al., 2017; Brykman et al., 2021; Counts et al., 2021; Heller et al., 2017). Commentators have noted several challenges in the potential use of VBP for children with special health care needs, including “low prevalence of specific special health care need conditions, how to factor in a life course perspective, in which investments in children’s health pay off over a long period of time, the marginal savings that may or may not accrue, the increased risk of family financial hardship, and the potential to exacerbate existing inequities across race, class, ethnicity, functional status, and other social determinants of health” (Bachman et al., 2017, pg. S96). Other challenges noted include measurement issues (lack of measures appropriate to subspecialty care or data systems in place to systematically collect data) (Bachman et al., 2017); complexity of pediatric patients who receive subspecialty care and the need to consider individual and family-specific circumstances (Kevill et al., 2019); and potential mismatch between outcomes in VBP and family or patient preferences for care (Anderson et al., 2017; Garg et al., 2019). Still, others believe that VBP holds promise to align payment with medical needs of children with complex needs and could be a promising avenue to advance high quality care for children.