2023 Nobel Prize Summit: Truth, Trust, and Hope: Proceedings of a Summit (2023)

Chapter: 3 MAKING SENSE OF MISINFORMATION

3

TRUTH, TRUST, AND HOPE

MAKING SENSE OF MISINFORMATION

The summit continued with further consideration of the current landscape and the challenge of making sense of misinformation through a series of short presentations, dialogues, and discussions. Moderator Kelly Stoetzel began with a series of questions that the sessions were designed to address: What makes societies vulnerable to today’s particular brand of misinformation? What is known about how human minds work when it comes to truth and untruth? If even the most vigilant are susceptible, is there hope for the future?

IS SEEING BELIEVING?

Illusionist Eric Mead provided a dramatic demonstration to show that everyone is vulnerable to misinformation. He began with several sleight-of-hand tricks with a volunteer such as the cups and balls trick, then stepped back to explain how he could fool the volunteer (and the rest of the audience).1 “Everyone is susceptible to being fooled, no matter how educated or on guard they are,” he stated. “Senses can be deceived. Certainty is an illusion.”

Humans have evolved to have “pattern-seeking brains” that are open to suggestions based on biases, he explained. Numerous studies confirm that humans are more likely to accept as truth something that confirms what they already believe and discard something that challenges their preexisting beliefs. To harden against the “tsunami of misinformation,” he urged recognition that

___________________

1 For more information about his demonstration, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GXVGji2KD7w.

humans can be fooled and that assumptions should be questioned. But he also expressed some hope. “We’ve been here before,” he said. When photography was introduced in the 19th century, people were deeply suspicious of the images, but they learned to discern what was real. This distrust happened again with image-editing software in the 1990s. “I believe we will learn to deal with new tools and use them for our benefit and not our ruin,” he said. In the short term, however, he predicted a backlash and distrust of digital life, and perhaps more person-to-person interaction.

THE INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM

Three short presentations followed: on memory, the reasons behind the spread of misinformation, and ideas to heal the troubled information ecosystem.

THE MISINFORMATION EFFECT

Elizabeth Loftus (University of California, Irvine) shared her research on memory. She contrasted semantic, fact-based memories with the focus of her research, which is on personal memories that are more impressionable, and

SOURCE: Elizabeth Loftus, Nobel Prize Summit, May 24, 2023.

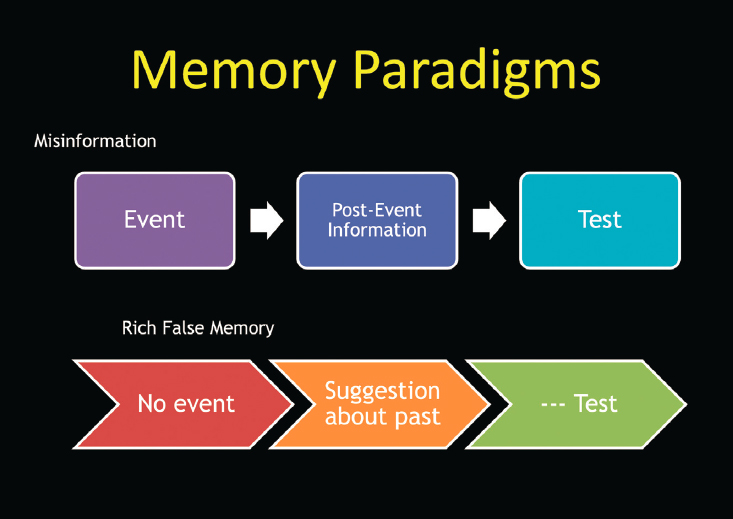

for which she has developed several paradigms. She elaborated on one of them, called “the misinformation paradigm.” She and colleagues conduct studies in which people witness an event, then receive information after the event that is misleading or manipulative. When they are tested about what they remember, they often recount the incorrect memory. In keeping with the theme of the summit, Loftus said it is important to study misinformation memories with these memory paradigms because misinformation is everywhere (see Figure 3-1).

Another type of false memories are those in which people begin to believe that they have undergone traumatic experiences in their past, and she wondered, as a scientist, how people could develop these false memories. She said a new procedure was needed to research this type of “rich false memory.” One study planted a false memory that a person was lost as a child, then rescued. Other upsetting false memories were planted with people, such as being attacked by an animal or committing a crime. A meta-analysis showed that about 30 percent of the subjects developed a false memory and another 23 percent developed a

false belief that such an incident had happened to them, even without a specific recollection. False memories have consequences, she continued. False memories can be felt with as much emotion as true memories, and imaging shows that the brain has similar neurosignals between true and false memories.

As an example, she pointed to push polls, which are used to infiltrate false information to participants, for example, about a politician. In an experiment, three different levels of information were planted about a politician cheating on her income tax, none of which was true. Many of the respondents began “remembering” the politician’s tax problems. Doctored photographs, deepfake technology, and artificial intelligence (AI) are also threats, she noted.

Loftus said this work raises ethical questions about when and how mind technology should be used and regulated. As a take-home lesson, she underscored, “Just because someone tells you something and they say it with a lot of confidence, just because they give you a lot of detail about it, just because they have a lot

of emotion, it does not mean that it really happened. You need independent corroboration to know whether you are dealing with an authentic memory or one that it is a product of another process.”

WHAT DRIVES THE SPREAD OF MISINFORMATION

To shed light on why people share misinformation, Gizem Ceylan (Yale University) related that in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, an art gallery owner shared a post on social media with inaccurate medical advice about how to prevent the virus’s transmission, such as not to drink liquids with ice. In a matter of days, his post went viral. She said what is interesting from a research perspective is that even after the poster knew his information was inaccurate, he did not change his sharing behavior. He continued to share false information.

Ceylan explained that her work looks at why people spread misinformation. According to her research, one of the reasons is the reward structure on the social media platforms. As with other behaviors, people develop certain online behaviors that receives rewards within their social media environment. On social media, these rewards are often social in the form of likes, comments,

SOURCE: Gizem Ceylan, Nobel Prize Summit, May 24, 2023.

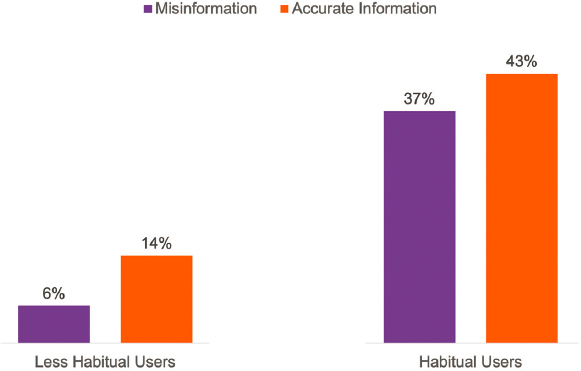

and followers. Over time, repeating the behaviors that bring the most social rewards make users’ behaviors more calibrated towards likes, followers, and similar rewards. This, in return, reduces their sensitivity to truthfulness of the information. The more people are exposed to this reward-based learning and become habitual sharers, the less sensitive they become. To test this, she and colleagues conducted a series of experiments with more than 2,000 social media users. Users received true and false information and were asked which messages they would share. The research team also measured to what extent users were habitual news sharers on social media. Less habitual users shared little of the information, as might be expected, and importantly, were more sensitive to the truthfulness. Habitual users not only shared more information, but also they were less sensitive to the truthfulness of the information they shared (see Figure 3-2).

Ceylan noted the implications that habit, rather than a lack of information or bias, is at the basis of sharing. For example, she suggested that interventions might target the reward structure. In another experiment, the research team changed the rewards people received for sharing. In one condition, people were

given rewards for sharing accurate information and in another condition, people were given rewards for sharing inaccurate information. Then the rewards were removed (Ceylan et al., 2023). When people rewarded for accuracy early on, they developed habits to share accurate information even when rewards were removed. Similarly, they developed habits to share inaccurate information when this behavior was rewarded early on. She said her findings show that misinformation-sharing behavior can be reduced with a new reward structure that focuses people on accuracy rather than popularity. Going back to the post about the pandemic with which she began her presentation, she conjectured that if the post had not received as much attention or some people called him out for not sharing accurate information, the person who posted it may have developed different sharing habits.

HEALING OUR TROUBLED INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM

Melissa Fleming (United Nations) recalled the excitement about social media among professional communicators for its ability to reach people directly at scale. Social media has accomplished positive things, but a dark side has also emerged. For example, refugees were initially welcomed in Europe in 2015, but soon bad actors began spreading lies online and the welcome soured. Similarly, in searching for information online for a personal cancer diagnosis, she found that a highly misleading site with nonproven remedies, called “The Truth about Cancer,” ranked high in the search results. The people behind the site are part of what the Center for Countering Digital Hate has named the “Disinformation Dozen”: the 12 originators of about 65 percent of the vaccine disinformation circulating online.2 The United Nations has observed hesitancy to obtain not only COVID-19 vaccines but also childhood vaccines in African countries that are usually pro-immunization.

In conflicts, she worries that social media is being weaponized by genocidal governments to provoke conflicts and dehumanize people, such as violence against the Rohingya people.3 Social media is also used to “increase the density of the fog” around atrocities and war crimes. Hate speech is being normalized, and the United Nations (UN) is under attack with false allegations against its peacekeepers. Social media is being used to undermine the science of climate change to silence scientists and activists. She also expressed concern that generative AI can take disinformation to a new level.

___________________

2 For more information, see https://counterhate.com/research/the-disinformation-dozen.

3 For more information, see https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/08/1139977.

The UN is stepping up its online communications, but she noted the challenges. Almost anyone can promote disinformation on X, formerly Twitter, she observed. She shared that the UN is trying to team up with the platforms and to work with an “army of trusted messengers” who want to promote UN content. An educational campaign is underway to suggest users “pause” before they share something and to think through who made the information, what is the source, where did it come from, why you are sharing it, and when was it published.

“We are in an information war and we need to massively ramp up our response,” Fleming said. To this end, she shared that the UN is creating a central capacity to monitor social media, rapidly react to misinformation and disinformation, and verify accurate information about climate change. The UN is also developing a code of conduct with a commitment to information integrity. She noted that those who want to create a more humane information ecosystem vastly outnumber the “haters,” and she urged people to join forces.

COMMUNICATING SCIENCE IN A POST-TRUTH WORLD

A conversation followed on tools to deal with the ecosystem outlined by previous presenters. Åsa Wikforss (Stockholm University) and Kathleen Hall Jamieson (Annenberg Center, University of Pennsylvania) elaborated on three topics: the insights they would like to see more prominently featured in discussions of mis- and disinformation; ideas to reduce public susceptibility to misinformation; and suggested actions for summit attendees to take.

RESEARCH INSIGHTS THAT DESERVE MORE ATTENTION

Wikforss reminded the audience about the social dimension of knowledge. As with other animals, humans gain knowledge through what they see, hear, and feel. But unlike other animals, much of what people know—including scientific knowledge—is not from direct experience but from reliable sources. This is a great strength for humanity but also a great vulnerability, because knowledge requires trust. Disinformation is aimed at undermining trust of reliable sources and instilling trust in unreliable sources.

Jamieson called attention to susceptibility to mis- and disinformation. Protective knowledge can lay the groundwork to minimize susceptibility and provide an armor when faced with it. She urged communicating clearly that scientific knowledge is provisional and constantly being updated. When new knowledge is gained, it is important both to share the new knowledge and to explain how it became known. To understand what happened during COVID-19, researchers at the Annenberg Center funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation analyzed thousands of contorted claims and found they fell into seven categories, such as the origins of a virus or vaccination safety. These categories suggest the areas where the public’s “protective knowledge” against being susceptible to mis- and disinformation should be strengthened, she commented. For example, explanations are needed about why an immunization is safer than getting the disease it is preventing. (She stressed using the language “safer than” because there will be some side effects for a small percentage of people).

REDUCING PUBLIC SUSCEPTIBILITY TO MISINFORMATION

Wikforss noted that when most nonscientists learn new information, they are not experts, and it is hard for them to respond when someone challenges the information. She countered those who do not trust science by stressing that while individual scientists do have biases, the institutions of science are set up to counteract individual biases and skewed reasoning through questioning, critical thinking, and peer review. These characteristics are applicable to other reliable institutions, including how the media is set up to weed out error, but the public does not always appreciate this, in her view.

Jamieson observed that the exchange among scientists, which characterizes the field, sometimes looks to the public as confusion. “The way we [scientists] communicate gets in the way,” she asserted. As an example, she pointed to recent research that showed the need to change the name of the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (Annenberg Public Policy Center, 2023). As she explained, “The way in which those nouns aggregate implies causality when everything at best is correlational. As a result, it seeds all sorts of deceptions.” It is an important system, she stressed, but the name and other system characteristics increase susceptibility to deceptions, and those deceptions are consequential for vaccination uptake.

TAKING ACTION TO INCREASE TRUST IN SCIENCE

Wikforss does not see a general lack of trust in science, but rather “a politically polarized loss of trust in science and in media.” Intentional politicization is

Just amassing a body of knowledge is not sufficient…. We have to learn how to apply that knowledge in different contexts, we have to see how it intersects with culture and society and values and understand they might clash, and we must be continually prepared to unlearn and learn new things. —Anita Krishnamurthi

fomented because science tells “inconvenient truths.” Scientists who find themselves in this situation must be careful in how they communicate, and must understand the distinction between science and policymaking, she said. Science can explain how to reach goals, but not what the goals or values should be, which should ideally be decided democratically.

Jamieson suggested some strategies to communicate science. Referring to the study mentioned above about categories of distorted claims, she noted that more than 100 of the claims arose through distorting published science, mischaracterizing the content of an article, mischaracterizing the author’s credentials, or mischaracterizing the credibility of the paper or journal. There are ways to preempt these distortions: retractions and corrections of flawed articles, clear writing that hews to the data to avoid confusion, verification of an author’s credentials through ORCID (Open Researcher and Contributor ID),4 and badging or other ways to verify the trustworthiness of a journal. “Science has the means to protect the integrity of its published knowledge,” she said, noting mischaracterized science that went viral could have been minimized with some of these actions.

DYNAMIC DIALOGUES ON TRUTH, TRUST, AND HOPE

In another way to engage in conversation during the summit, a series of three “dynamic dialogues” was held. Three thought leaders made short presentations on ideas that they believed could lead to truth, trust, and hope. Four “provocateurs” joined them on stage to delve deeper into their ideas. They were Leslie Brooks (American Association for the Advancement of Science), Roger Caruth (Howard University), DeRay Mckesson (Campaign Zero), and Sabrina McCormick (George Washington University).

___________________

4 For more information on self-authenticating of an author’s credentials through ORCID, see https://orcid.org.

THE PROMISE AND PROBLEMS OF SCIENCE

Nobel Prize laureate Martin Chalfie (Columbia University) acknowledged the promise of science but also the problems that he has seen facing scientists, engineers, and health professionals in his work as chair of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Committee on Human Rights. In addition to mis- and disinformation, he reminded the audience of the flooding of vast quantities of information, what has been called an infodemic. “There’s so much noise, it’s hard to find out where the right information is,” he said. In addition, there are attacks not just on information but on people. In some countries, professionals who speak about information that the government does not want the public to hear are dismissed from their jobs, harassed, threatened, and/or imprisoned. He cited Nicaragua as one example, where scientists who wrote about the environmental consequences of building a canal were dismissed and the Nicaraguan Academy of Sciences is no longer permitted to operate legally. Elsewhere, police have turned against health professionals who treat injured protesters; in Ukraine, an average of four health facilities are bombed every day.

Chalfie suggested education and laws as solutions, but also the power of bringing people together (e.g., health professionals worldwide). He also noted the authors of the book Infodemic: How Censorship and Lies Made the World Sicker and Less Free showed the power of local news organizations to bring information to people especially in underserved communities (Simon and Mahoney, 2022). Finally, he said, there is a right to science in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. “We should be bringing science to everybody,” he stressed.

Moving to dialogue with the provocateurs, Brooks asked about the implications of scientists who hold divergent views. Chalfie said dealing with and evaluating divergent views and controversy is part of the scientific process through open discussions. Caruth concurred with the importance of local news and underscored the danger of its demise; he agreed that media and scientific communities must work together. McCormick observed that people are often in “echo chambers” listening only to channels that reflect their political views and asked about entertainment as a way to transcend this. Chalfie welcomed the idea because “anything that makes people think helps,” and science can be a vehicle through which to talk about many things. Mckesson asked how to stem the flooding of information. Chalfie acknowledged the challenge when bad actors want to flood media. As an antidote, he called attention to the Documented project in New York City. By first listening to immigrant communities and gaining trust, members of those communities come to them with questions, for example

about COVID-19.5 Brooks reinforced the need for listening and sharing, noting the competitiveness among some scientists not to be open. Chalfie said when he discusses his science openly, he always gains new ideas.

EDUCATION AS AN ACT OF HOPE

Anita Krishnamurthi (Collective for Youth Empowerment in STEM and Society [CYESS], Afterschool Alliance) shared that she pondered what she would say as a science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education advocate at a summit with the theme of truth, trust, and hope. “Then it hit me,” she said. “Education is an act of hope.” People gain skills to make a living, engage with others, and apply knowledge to help themselves and their communities. There is also an implicit belief that education will inoculate people against misinformation and disinformation, she continued. But just amassing a body of knowledge is not enough to realize the potential, she stressed. The ability to develop and sustain

___________________

5 For more information about Documented, see https://documentedny.com.

There is a right to science in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. We should be bringing science to everybody. —Martin Chalfie

Krishnamurthi also observed that the narrative case for STEM education and learning both in school and out-of-school programs has become transactional:

curiosity in order to respond rather than react to challenges is a muscle that has to be developed and strengthened through practice. A learning ecosystem where this muscle can be exercised in different settings can help, starting with young children. She observed that current metrics are not nuanced and may not be able to measure what is truly important. To change the paradigm, she noted the work of many organizations, such as the critical thinking curriculum launched by Nobel Prize Outreach, and pedagogy in some countries, such as Finland.6 While it is tempting to pick a program and scale it up, she cautioned that context matters. “Things have to be adapted to a local community,” she said.

___________________

6 For more information on Nobel Prize Outreach, see https://www.nobelprize.org/the-nobel-prize-organisation/outreach-activities; for information on the “Scientific Thinking for All: A Toolkit” curriculum, see https://www.nobelprize.org/scientific-thinking-for-all.

that is, learn a STEM field to get a job. While this is important, she urged expanding the STEM narrative to include STEM as a tool for public good and effective citizenship. She launched an initiative called the Collective for Youth Empowerment in STEM and Society as part of the Afterschool Alliance to bring together organizations working at the intersection of STEM, civic engagement, and teen leadership to give young people a voice and seat at the table to apply their STEM knowledge to community issues and help to enact systemic change.7

Moving to the provocateurs, McCormick reflected from her own research about the climate anxiety and desire to take action among many youths. For this reason, Krishnamurthi explained, CYESS supports existing programs to expand and amplify work that is currently happening in isolated pockets. Climate and data science are areas with a lot of this activity. Mckesson asked as a former teacher and afterschool provider about the components of a good STEM program. To Krishnamurthi, an important element is how a program brings STEM alive for the participants. Even if the providers are not STEM experts, they can be experts in engaging with young people and can use that skill to bring about agency and confidence in STEM. Contextualizing STEM in the community to show it is relevant to their lives engages young people. Being unafraid is a key characteristic of a good STEM educator, even if the provider does not know the answers. There is always a need for more resources and partnerships, she added. A commitment to co-designed, co-learned offerings is a hallmark of a good STEM program. Brooks asked about resolving science with culture and politics, and how to educate the upcoming STEM workforce. Krishnamurthi acknowledged that science intersects with culture, and it is important to think of the end goal and common ground between scientists and nonscientists. Caruth reflected on the role of education and hope in his own life, and asked about ideas for those who see their situations as hopeless. Krishnamurthi responded that it is important to continually look at how to bring programs, resources, and mentors into communities and show what is possible. Poverty and other needs must be addressed that go beyond science literacy. It is important to support the community to thrive, which goes beyond science.

MARKERS OF TRUST

Through her work with people fighting for racial justice in evangelical megachurches, Hahrie Han (Johns Hopkins University) recalled a pastor whom she knew asking her to share information on vaccines that he could share with

___________________

7 For more information on CYESS, see https://cyess.org.

other clergy. As she reflected on what to send, she pondered, how do we know what we know? In the modern era of hyperspecialization, people often have specialized knowledge, but then use social cues to identify trusted information from others. In this example, Han realized she was relying on “markers of trust” about mRNA vaccines, lacking knowledge about the actual biology at play. Different people have their own markers of trust, or sources they find trustworthy. Thus, simply throwing scientific information at vaccine deniers is not effective if they do not see science as a trustworthy source. It is more effective to find messengers they already trust to impart information.

The challenge in the current moment is finding trusted messengers. The structure of social spaces that cultivate the connections people need to identify such messengers has changed dramatically in recent decades, Han continued. She made three observations. First, people go through life with many social interactions but few social relationships. Second, many relationships tend to be transactional exchanges rather than social exchanges that engender trust. Third, the disintegration of civic infrastructure means that the social relationships that do exist tend to be among homogenous people.

In thinking about how to respond to her pastor friend, Han recalled that his megachurch has thousands of worshippers, but manages to cultivate an intimate sense of belonging. One motto of the church, she said, is “belonging comes before belief.” This message contrasts with most social spaces, where belief comes first. She argued that people are looking for belonging all over the world.

Caruth reflected on the power of the church in the Black community and noted that receiving information from someone trusted is usually accepted, but sometimes the information is not accurate. Han suggested that experts should work with faith institutions so their leaders can help understand what it true. Mckesson asked about any areas of surprise in her research related to trust and community building, especially given recent trends that America is becoming less spiritual. Han replied that while the median U.S. church (with 100 members or fewer) is declining, megachurches (defined as 2,000 members or more) are growing. The largest 9 percent of churches contain 50 percent of the church-going population in America. In her view, people are searching for communities of belonging. McCormick noted that in the climate space, people

We need to embrace our paleolithic brains, upgrade medieval institutions, and bind godlike technology —Tristan Harris

have a set of values or norms that makes them think that climate change is or is not relevant to them. Han said the transformative power of social relationships is often underestimated. “When combating disinformation, we have to address not only the messaging, narrative, and ideas, but also the social infrastructure,” she said. Brooks asked for actionable steps in developing a sense of belonging in health-care settings. Public health agencies and community organizations are opportunities that are sometimes not fully realized as opportunities for connection and belonging, Han suggested.

“I’M NOT AFRAID. YOU’RE AFRAID”

Tristan Harris (Center for Humane Technology) introduced his ideas by quoting Harvard sociobiologist E. O. Wilson, who said the real problem of humanity is that “we have paleolithic emotions or brains, medieval institutions, and godlike technology.”8 The challenge is how to find alignment, Harris said, which AI only turbocharges. Harris was involved in the documentary film The Social Dilemma (Orlowski et al., 2020), which highlights the effects of social media on humanity. “First contact” with AI and social media caused people to experience information overload, addiction, influence or cancel culture, shortened attention spans, and other conditions. Collectively, these effects are like the climate change of culture, he posited. Now, he said, “second contact” with AI, through large language models, is coming without having fixed the first misalignment. Despite companies’ messaging that social media connects people or provides them with the information they want, underneath is the race to maximize engagement. As he noted, social media platforms are free to users, and the companies make their money through users’ data and attention. The goal of social media companies is “to get you addicted to needing attention,” he asserted. The creation of likes, reposts, and other sharing builds on this. In addition, extreme voices post more often than moderate voices, and extreme statements become viral. Therefore, a small number of extreme voices have an oversized effect, leading to a “funhouse mirror” and a distorted world.

___________________

8 Statement by E. O. Wilson at a debate at the Harvard Museum of Natural History, Cambridge, Massachusetts, September 9, 2009. Available at https://www.harvardmagazine.com/2009/09/james-watson-edward-o-wilson-intellectual-entente.

The complexity of the problem has exceeded such responses as content moderation, fact-checking, or vilifying Big Tech CEOs, Harris said. The key to closing the complexity gap, he contended, is wisdom. Governance must be upgraded to match the complexity of the world. Referring back to the Wilson quotation, he said, “We need to embrace our paleolithic brains, upgrade medieval institutions, and bind god-like technology.” For example, social media business models could be reconfigured to build social fabric and showcase physical communities over virtual communities, he suggested. Institutions are set up to deal with acute harms over diffuse chronic harms, such as climate change or mental health. But they should be able to deal with chronic, not just acute, issues. Recognition of the race to create virtual influence must be addressed.

Quoting social philosopher Daniel Schmachtenberger, Harris concluded, “You can’t get the power of gods without the love and wisdom and prudence of gods.”9 Having more power than wisdom or responsibility results in creating effects in society that cannot be seen, Harris said. The biggest mistake of social media, he said, was to hand out godlike responsibilities to those not bound to wisdom. He cautioned about the growth of generative AI without wisdom.

ALL INFORMATION IS LOCAL

Striking a balance between free speech and preventing the spread of disinformation was the focus of the final group conversation. Finn Myrstad (Transatlantic Consumer Dialogue) moderated a session with Rebecca MacKinnon (Wikimedia Foundation), Maia Mazurkiewicz (Alliance4Europe), Flora Rebello Arduini (Business and International Human Rights Law Expert), and Rana Ayyub (Investigative Journalist).

ON-THE-GROUND CHALLENGES

MacKinnon distinguished between misinformation and disinformation (see Chapter 1) and noted that the Wikimedia Foundation has observed that disinformation is often accompanied by threats against those who try to counter the disinformation. Volunteer editors have been at the front lines of her platform in creating and enforcing rules about neutral content. Many were active during the pandemic to provide factual information in more than 200 languages. Others are documenting misinformation and disinformation about COVID-19 in a transparent manner.

___________________

9 Statement by Daniel Schmachtenberger at the Jim Rutt Show. Available at https://jimruttshow.blubrry.net/the-jim-rutt-show-transcripts/transcript-of-episode-7-daniel-schmachtenberger.

Mazurkiewicz explained Alliance4Europe’s work fighting disinformation, in particular with the war in Ukraine. Russia and other bad actors are weaponizing science and other information in trying to polarize societies, she pointed out. The brains of people living in fear, including from the pandemic or war, shut down, and a fight-flight-freeze response is triggered by psychological fears, she said. Disinformation often works on fear. Alliance4Europe is working with partners to research how to respond, including positive communication.

Rebello Arduini reflected on the role of disinformation and hate speech in Brazil and in other countries. Bad actors call for violence, and the big tech platforms amplify their messages because they want to monetize content. Although authorities tried to stem it, these messages led to the disturbances in Brasilia on January 8, 2023, which were a copy of those that took place in Washington, DC, on January 6, 2021, she said. Rioters believed the elections were rigged because they had received this message for years. Brazil’s government and civil society have been looking for solutions, including regulations.

Ayyub worked as an undercover investigative journalist to expose systematic persecution of religious minorities in India. She herself is now the subject of

harassment and disinformation. When asked about the media landscape in her country, she stated, “The media landscape does not exist in a country of 1.4 billion people. The mainstream media has been captured by the state.” She commented that the Nobel Foundation awarding its Peace Prize to journalists “acknowledges that journalists are now considered the enemies of the state.” They have been discredited with disinformation and misinformation. She commented that when she “Googles” herself, false stories appear first in the search results. She cited several examples of disinformation by authorities in India that have taken on the appearance of reality in the absence of an independent media.

SYSTEMIC AND INDIVIDUAL ACTIONS

To suggest areas of hope, Myrstad asked the panel for suggestions at the systemic and individual levels. MacKinnon stressed independent journalism, science, open data repositories, open libraries, free knowledge projects such as Wikipedia, and the like, are the best antidote to mis- and disinformation, and the people involved in these functions must be protected. Laws and regulations do not prioritize this responsibility, she said. However, she added, when addressing harms, it is important not to make it even harder for truth-seeking people to do their work without being sued or threatened.

Smart regulations can help, Mazurkiewicz said, especially with AI advances. Coming together can develop solutions. She also recommended media literacy and critical thinking legislation.

Rebello Arduini offered several ideas. First, she called for regulations, such as the European Union’s Digital Services Act,10 because self-regulation by companies has not worked. Second, public policy is needed to support digital literacy. Third, an independent press is necessary. The best antidote for disinformation is accurate information. Journalists must be able to flourish, not perish. Fourth, social media platforms should treat citizens around the world equally and should invest in ethics and security.

Ayyub was offered the last word. The goal of the government has been to silence her, she said, but she continues to speak up. “We do not have the luxury of being silent,” she stressed. It is exhausting, but dictators and demagogues want quiet. Support independent journalists, she urged. History will record the “silence of the well-meaning.”

___________________

10 Regulation on a Single Market For Digital Services (Digital Services Act), Regulation (EU) 2022/2065, DSA.