2023 Nobel Prize Summit: Truth, Trust, and Hope: Proceedings of a Summit (2023)

Chapter: 4 SEEKING TRUTH

4

TRUTH, TRUST, AND HOPE

SEEKING TRUTH

The final “chapter” of the Global Conversation sought practical ways to find truth and build on hope. As moderator Kelly Stoetzel stressed, “Where there is truth and trust, there is hope.” Ideas related to poetry, community initiatives, science, and independent journalism were shared by a range of speakers, including four Nobel Prize laureates.

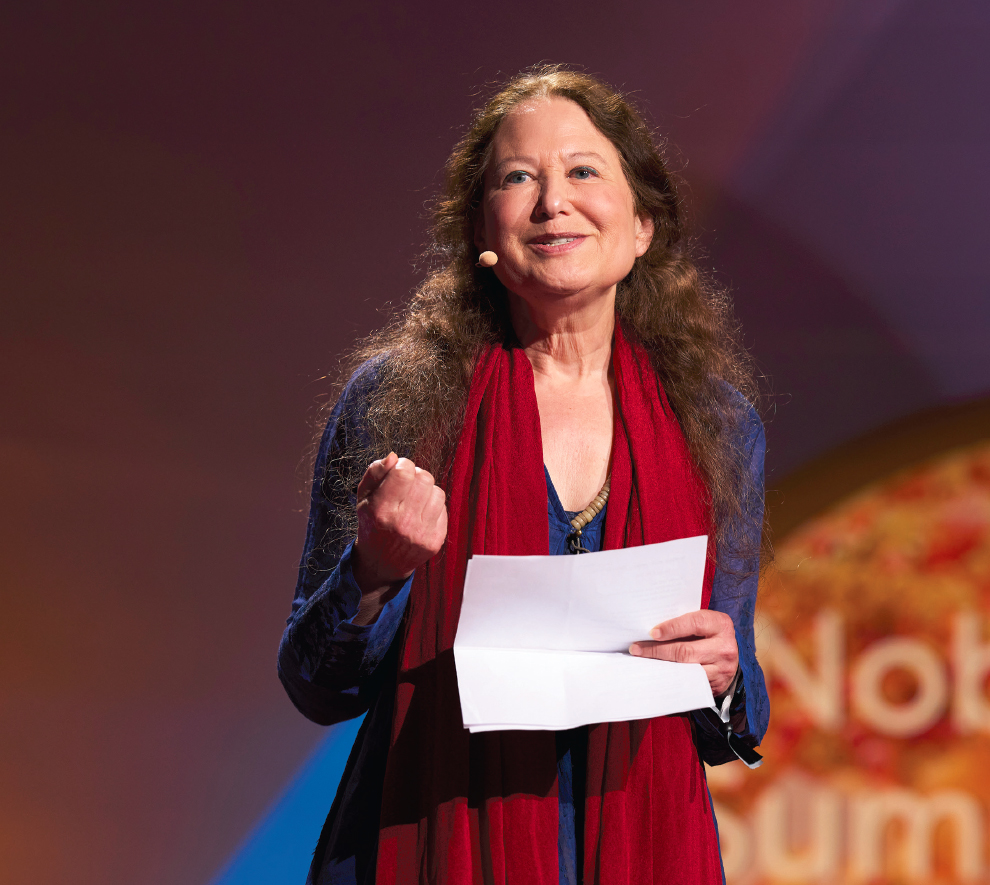

THE POWER OF POETRY

Poetry might seem an unusual addition to a conference in support of facts and truth at the National Academy of Sciences, acknowledged Jane Hirshfield (Poets for Science). But, she continued, “the microscope and the metaphor, and imagination and observation, are not separate.” Science and art began in prehistory as a single endeavor, as early humans sought to understand their experienced world. Now, people turn to science for questions that can be answered and to art for questions that cannot be answered but still require a response. Both disciplines are acts of discovery and both distill complex thought into memorable symbolic form. Both are practiced continually but are most

needed in times of crisis. Each borrows the other’s strengths: poets observe and scientists need imagination to formulate new hypotheses.

Poets for Science began as a response to censorship and the silencing of facts, she reported. She recalled January 24, 2017, the day the previous presidential administration removed all mention of climate change from the White House website and required federally employed scientists to obtain preapproval before speaking publicly of their research. “By the end of the day,” she reported, “I had written a poem,”1 and by the April 20th March for Science in Washington, DC, Poets for Science had been founded, offering writing workshops in a tent covered with banners of poems about science, the same banners on display at the National Academy of Sciences for summit attendees to read.2

Hirshfield closed by noting that allegiance to the factual is foundational for survival, but that for the work of changing a culture, the sense of shared experience and shared lives carried by the emotions—and by the arts—are equally essential.

David Hassler (Wick Poetry Center, Kent State University) reported on a poetry workshop he conducted with several summit participants over the past weeks to discover the emotional truth of science. They read the poetry of others and then composed their own works, Hassler reported. On the summit stage, several participants, including Hassler, shared a collective poem.

A FRAMEWORK FOR THE FUTURE: TWO NEW APPROACHES

Presenters shared two new initiatives to which they invited participants to connect: the International Panel on the Information Environment (IPIE), introduced by Sheldon Himelfarb (PeaceTech Lab) and Philip Howard (Oxford University), and an open-source solution challenge issued by the Digital Public Goods Alliance and the United Nations Development Programme, introduced by Nicole Tisdale (Advocacy Blueprints).

INTERNATIONAL PANEL ON THE INFORMATION ENVIRONMENT

The International Panel on the Information Environment, or IPIE, came out of

___________________

1 To read Hirshfield’s poem “On the Fifth Day,” go to https://poets.org/poem/fifth-day.

2 For information on the exhibit held at the National Academy of Sciences, see https://poetsforscience.org.

the 2021 Nobel Summit as a convergence of local change making and research. Himelfarb explained he has been involved in efforts to develop technology tools, strategies, and training so communities can do “more, better, faster” to tackle drivers of conflict. Howard and his lab at Oxford work to identify the complex information operations that degrade public life. The common denominator between their career trajectories, Himelfarb suggested, is how technology can be used to amplify the social good.

“Misinformation is causing widespread social harm. It will only get worse unless we act,” Howard said. AI accelerates the problem, and policymakers are struggling to keep up. Howard and Himelfarb highlighted the work of several researchers to understand facets of the problem and develop solutions at universities, companies, and think tanks. For example, Sebastián Valenzuela (Pontifical Catholic University of Chile) demonstrates the role of social media and youth engagement, Young Mie Kim (University of Wisconsin–Madison) studies digital media and political communication, Mona Elswah (University

of Oxford) examines misinformation and state-backed media outlets, Charlton McIlwain (New York University) is the author of Black Software: The Internet and Racial Justice, from the AfroNet to Black Lives Matter,3 Patricia Kingori (University of Oxford) studies misinformation and pseudoscience, and Molly Crockett (Princeton University) studies neuroscience behind the cultural war. To harness the collective power of their work, IPIE involves researchers in engineering, social sciences, and other disciplines from around the world who are driven by the critical questions that come out of the humanities. A science advisor is helping to identify gaps and find evidence-based solutions, at a speed commensurate with the urgency of the problem, with the mRNA vaccine and deployment of the James Webb Space Telescope as two examples of how this can be done. Large language models can cause problems but are also part of the toolkit, Howard suggested. IPIE now involves 200 research scientists in 55 countries, with funding from six philanthropies.

___________________

3 New York: Oxford University Press, 2020.

Research has already pointed to two promising operational practices to fight misinformation and disinformation: flagging questionable content before users “go down the rabbit hole” and providing accurate information immediately. Through IPIE, research scientists are self-organizing to do what legislators, regulators, and corporations have struggled to do, they said. IPIE stands on the shoulders of other collaborative organizations, including the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, CERN (European Organization for Nuclear Research), and the Union of Concerned Scientists. Scientists have been working “in their own backyards,” but a multidisciplinary collective effort is needed. Himelfarb invited participants to become involved with IPIE.

OPEN-SOURCE SOLUTIONS CHALLENGE

Tisdale noted she works in Washington policymaking, but travels around the country, where she hears a lot of disinformation about government and politics. As a response, in February 2023, the Digital Public Goods Alliance and the United Nations Development Programme issued a global call to develop open-source solutions to fight disinformation and strengthen information integrity. Noting the irony of looking for a digital solution to fight a digital problem, she countered that disinformation disproportionately affects human rights and development in countries with weaker democratic institutions. Open-source tools can fight this, she said, because these tools are transparent to the people who create and use them, are accessible, and can empower users. Of almost 100 entries, 9 solutions were selected to pave the way toward a more trustworthy and informed digital future.

The solutions hold Big Tech accountable in a variety of ways, such as through more transparent algorithms and authentication.4 She urged anyone who is developing tools to focus on inclusivity and collaboration, which means thinking about linguistic and language needs, social and political constructs, and cultures of the communities. She urged participants to view, but more importantly to use, the tools that were developed through the challenge.

A CONVERSATION WITH NOBEL PRIZE LAUREATES: TRUTH, TRUST, AND HOPE

In conversation with Sudip Parikh (American Association for the Advancement of Science [AAAS]), Nobel Prize laureates Saul Perlmutter (University of

___________________

4 More information about the challenge and solutions is available at https://digitalpublicgoods.net/information-pollution.

California, Berkeley), Richard Roberts (New England Biolabs), and Donna Strickland (University of Waterloo) recapped some of the themes throughout the day through their prisms as scientists and Nobel Prize laureates. Addressing the historical context, Perlmutter pointed out that science has always aimed to discover truth and provides a way for people to build trust together as a collaborative activity. Strickland posited that while scientists have always engaged in extensive discussion and peer review, the current time demands that scientists do more than talk with each other.

Roberts agreed the summit had reinforced the importance of communication with the public, especially children. He also noted the importance of in-person communication. Perlmutter said “science education” should impart not just the content of biology, chemistry, or other subjects, but also the process of “how science works.” Regarding education, Roberts urged more creativity and asking of questions, and Strickland observed that much of teaching science to children focuses on what is already known, rather than letting them explore what is not known.

As the panel noted, what is rewarding for scientists is when they realize that what they thought was wrong. “The fun of the game is finding out what you didn’t expect,” Perlmutter said. Roberts said when experiments fail and are reviewed to understand why, this is where the big discoveries occur. Extending this idea to the fight against misinformation, he pointed out that it will be a long process and some things will not succeed, but it is important to keep trying. Strickland said scientists must explain why they are saying something, but she acknowledged the difficulty in the “age of the sound bite,” when it is hard to explain an idea in a few seconds. Although people became frustrated during COVID-19, for example, as guidance about masking changed, they were watching a scientific experiment in real time for the first time in their lives. She said if scientists had had the time to explain and if people already understood the scientific process, this would have helped in the understanding of the changing knowledge.

To bridge the gap of trust, Perlmutter suggested finding ways to bring people into conversation, so scientists are not in the position of sages telling the answers.

Without facts, you cannot have truth. Without truth, you cannot have trust. Without these three, we have no shared reality. We have no democracy. —Maria Ressa

Scientists are not experts in values and choices, and they need to be part of a two-way conversation. Roberts stressed taking the time to learn how to communicate with the public. He suggested making sure that science students are taught to communicate with the public. He offered “the grandmother test”: that students are able to explain their research to their grandmother, who then can explain it to her friends. Strickland concurred with the need for two-way conversation, and said that the University of Waterloo is creating a trust network.5 It is important to listen to communities about why they do not trust science and work with social scientists to experiment with solutions.

When Parikh asked the laureates what they are hopeful about, Perlmutter said meetings like this are a great opportunity for hope. Roberts noted that a gold standard for facts does exist in many fields, and suggested a database that people could trust, perhaps as a productive use of AI. Strickland said she is hopeful that while lack of trust is a global problem, people are finding solutions.

HOPE HAS A PLAN

Nobel Prize laureate Maria Ressa (Rappler) expressed in a closing keynote speech that the only weapon that a journalist has is to shine the light on truth with the support of others. Big Tech has moved exponentially, and efforts to counter it are moving more slowly. She clarified the problem is not misinformation, but disinformation, when power and money use the existing information ecosystem to insidiously manipulate the cellular level of democracy. “Misinformation” whitewashes what is really happening, in her view.

She said the way to emerge is to ask people what they will sacrifice for truth. She noted that her book How to Stand Up to a Dictator: The Fight for Our Future has been translated into many languages with the goal of moving people to act (Ressa, 2022). Silence is complicity, and individual courage will determine the

___________________

5 For information on the Trust in Research Undertaken in Science and Technology (TRUST) Scholarly Network, see https://uwaterloo.ca/trust-research-undertaken-science-technology-scholarly-network.

fate of humanity, she stressed. “Death by a thousand cuts” can result in loss of democracy, and it is something that terrorists have recognized and used. At Rappler, which is an independent news organization in the Philippines, she said she and her colleagues think of the worst case imaginable; by embracing it, “you rob it of its sting.” She urged the audience to “embrace your fear.”

Ressa helped develop and is now seeking support for the 10-Point Plan to reclaim rights from Big Tech that includes a stop to surveillance for profit, a stop to coded bias, and journalism as an antidote to tyranny.6 She noted that the first generation of AI deployed microtargeting based on cloned data, but generative AI will be exponentially more powerful. Governments have abdicated responsibility for protecting the public sphere, and tech companies have become the new gatekeepers, she underscored.7 They have separated content from distribution and can spread lies, laced with anger and hate, faster than facts.

“Without facts, you cannot have truth. Without truth, you cannot have trust. Without these three, we have no shared reality. We have no democracy,” Ressa said. The information ecosystem makes it hard to believe in the goodness of humanity, she conceded. Most of the world is under authoritarian rule, and many authoritarian rulers have been illiberally elected, are forming global alliances, and are undermining democratic institutions. Ressa recounted that she has been dehumanized online, which she initially felt ashamed to share. However, she realized the need to speak out because she is not alone. A UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) report showed that 73 percent of women journalists have experienced online abuse, and 20 percent have been attacked or abused offline in connection with this online abuse (UNESCO, 2022). In her own case, she receives 90 attacks per hour with both professional attacks, to tear down her credibility, and personal attacks, to tear down her spirit. Disinformation comes both bottom up and top down, she added, as shown in the spread of lies about the January 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol to “stop the steal” of the election.

The pillars to rebuild trust are technology, journalism, and community. Regarding technology, she called for legislation such as the European Union’s Digital

___________________

6 For the full 10-Point Plan, see https://10pointplan.org.

7 In May 2023, the U.S. government announced new actions to promote responsible American innovation in artificial intelligence that protects people’s rights and safety, including the Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights. For more information, see https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/05/04/fact-sheet-biden-harris-administration-announces-new-actions-to-promote-responsible-ai-innovation-that-protects-americans-rights-and-safety.

Services Act and building of new safe platforms independent of Big Tech. She noted the launching of the Institute of Global Politics at Columbia University to bring together engineers, scientists, policymakers, and others. She also called for funding for journalism and to protect journalists, especially in the Global South. From her own experience, she highlighted Project Agos, a crowd-sourcing tool to empower people to prepare for, respond to, and recover from disasters.

“You cannot have integrity of elections without integrity of facts,” Ressa said. A whole-of-society approach is needed in the short term for the elections. The model used in the Philippines included fact-checking by news organizations; sharing the facts with influencers, who can add emotion to the facts and share them with their networks (in this regard, she said the only emotion that spreads as fast as anger is inspiration); research; and accountability. Partners started actively sharing each other’s work, which proved to be extremely powerful.