Ocean Acoustics Education and Expertise (2025)

Chapter: 1 Introduction

1

Introduction

Acoustics is the science of sound, encompassing its production, transmission, and reception. Sound is ever present in all environments and, as a discipline, has applications in the earth sciences, engineering and physical sciences, life sciences, health and human sciences, and the arts. As a sensory modality, sound and vibrations are used by both animals and machines to communicate and gather information about the conditions around them. This is particularly true in the marine environment, where sound travels more efficiently and over larger distances compared to light, which attenuates rapidly and often vanishes within a few hundred meters of the surface. This report specifically addresses ocean acoustics, but many of the topics and ideas can be thought of interchangeably with underwater acoustics in lakes, rivers, bays, etc.

Underwater sounds carry indicators of the state of the ocean, conveying both characteristics of their sources and their complex interactions with ocean boundaries, basic ocean physical properties (e.g., changes in temperature, salinity), and objects (e.g., fish aggregations, turbulent microstructure, clues to habitat health) within the ocean volume. Sound in the ocean is generated intentionally by natural sources (e.g., volcanoes, earthquakes, animals), by humans (e.g., active sonar, echo sounders), and as a by-product of human activity (e.g., shipping, recreation, construction). As a result, ocean acoustics is highly intertwined with the physical, biological, chemical, and geological aspects of the ocean that define the field of oceanography. Sound and acoustic technologies are a primary tool in marine commercial and recreational fisheries that play an increasingly critical role in global food security (FAO, 2022). Furthermore, sound is used to explore and exploit the mineral riches of the deep ocean, which has broad diplomatic and environmental implications. As evidence of the growing recognition of the importance of ocean acoustics, ocean sound was recently added to the list of essential ocean variables for the Global Ocean Observing System and is listed with both Physics/Climate and Biology/Ecosystems (GOOS, 2020).

The field of ocean acoustics was the first of five National Naval Responsibilities (NNRs) established on August 31, 1998 (ONR, 2000). The NNR initiative was developed with input from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies) and other organizations to provide stability to disciplines that are otherwise not supported by other branches of DoD or other federal agencies (TRB, 2011). However, there has not been a recent assessment of the ability of ocean acoustics education and expertise to keep up with workforce demands, not only within the USN but across the federal government, industry, research, and academia, or with advancements of acoustic platforms, technology, and capabilities. The last report on the issue was led by Lackie of the Applied Physics Laboratory at the University of Washington in 1997; it is over 25 years old and focused solely on naval applications.

Beyond fundamental ocean science, the discipline of ocean acoustics is expansive and continuing to grow. Its expertise is vital for several economic, environmental, and national security applications. At the national level, the Interagency Working Group on Ocean Sound and Marine Life has been tasked with coordinating and facilitating activities related to ocean sound among federal agencies. Ocean acoustics, both active and passive, is also the basis for technologies critical to the development of the blue economy and sustainable use of the ocean (EOP, 2022a, 2023). This has been highlighted in the presidential memorandum directing the development of a national strategy to map, explore, and characterize the U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone (EOP, 2022b). Acoustics is also critical to ocean energy development, as demonstrated by the recent establishment of the Center for Marine Acoustics at the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM). As our understanding of the ocean grows, and our exploitation of its resources change with the developing blue economy, effects are anticipated on the acoustic environment of some marine habitats, creating the necessity of addressing how to wisely use acoustics for ocean exploration and development.

INTERDISCIPLINARY CHALLENGES

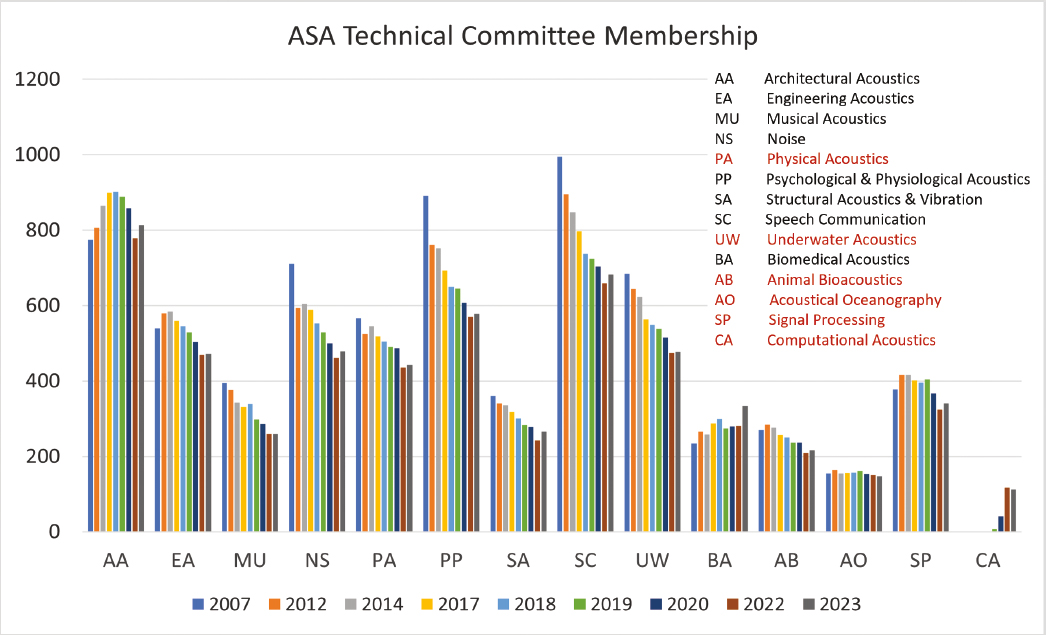

The field of ocean acoustics is complex, stemming from the inherent interdisciplinarity, integrating knowledge and skills from mathematics, the natural sciences, and engineering. The expanding applications of ocean acoustics, relating to biology, ecology, oceanography, and conservation, to name a few, contribute to an increasing need for additional education and training opportunities to support a robust workforce. The increasing diversification of ocean acoustics applications is evident in how the ocean acoustics community identifies with multiple Acoustical Society of America (ASA) technical areas (see Figure 1-1, red legend text). Within ASA,1 the community includes subsets of members from the following technical areas: physical acoustics, underwater acoustics (UW), animal bioacoustics, acoustical oceanography (AO), signal processing, and computational acoustics.

Figure 1-1 depicts the decreasing numbers of acoustics professionals in a majority of the ASA technical areas. This is likely due to a combination of several factors identified by the committee, from the survey, and during the information-gathering panels, including an aging workforce, stagnant growth of education and training programs, and weak recruitment and retention. This is not unique to ocean acoustics and supporting disciplines, as declining membership in the different ASA technical areas (Figure 1-1) is a common trend. Strikingly, AO is one of the few areas with a flat membership trend; however, this contrasts with the sharp decline observed in UW. Biomedical acoustics is the only subdiscipline that experienced growth over the past 15 years.

In the academic landscape, content in ocean acoustics, general acoustics, and supporting disciplines is included in the following formal degree departments: mechanical engineering, electrical engineering, computer engineering, civil engineering, computer science, biology, physics, aerospace engineering, oceanography, ocean engineering, geophysics, and marine science. Yet, none of these formal degree names explicitly convey knowledge or expertise specific to acoustics. Pennsylvania State University, University of New Hampshire (UNH), and University of Massachusetts Dartmouth are the only three U.S. higher education institutions offering programs with degrees or certificates at the graduate level that specifically convey acoustics expertise in the diploma or certificate title.2 Without a single discipline focus at the majority of U.S. institutions, students face challenges both during their educational matriculation and upon graduation, such as

- a lack of interaction and awareness of acoustics materials between different departments and programs that leads to low course enrollment and risk of cancelation;

- graduates with an emphasis in acoustics from programs in one discipline (i.e., mechanical engineering) encounter the challenge of being hired in other colleges/programs within academia (i.e., oceanography); and

- graduates with a degree in traditional programs do not convey acoustics knowledge to future employers, which results in a discipline with no true or visible identity, making it challenging to attract new students and retain graduates on a career path in ocean acoustics and supporting disciplines.

___________________

1 ASA is a professional society that attracts membership from academia, government, and industry.

2 Pennsylvania State University has a graduate program in acoustics, and both UNH and University of Massachusetts–Dartmouth have a graduate certificate in acoustics.

NOTES: The decline or stagnant membership trend in most technical areas indicates a decline of acoustics professionals. The year 2021 was omitted due to COVID. Red legend text identifies ocean acoustics and supporting disciplines relevant to the ocean acoustics community at large.

SOURCE: Committee developed with data from the Acoustical Society of America.

DIVERSITY IN AUDIENCE

As a historically naval discipline (Hackerman et al., 1990; Lackie, 1997), ocean acoustics has expanded with several direct applications, supporting the mission of federal agencies and organizations, industries, and nongovernmental organizations. As the need for ocean acoustics knowledge has grown and application of its techniques expanded, so too has the diversity of employers, career paths, education requirements, and students. The main avenue for education and careers was tightly linked to national security needs and supported by USN grants (Hackerman et al., 1990; Lackie, 1997). Although this relationship is crucial and still thrives today, new education and training opportunities outside of graduate-level education are necessary to meet expanding current and future workforce needs from a much broader portfolio of federal and industry stakeholders. In addition, the rapid growth of acoustic technologies requires that members of the technical workforce regularly update skills through formal schooling and professional development opportunities, including innovative and flexible training programs.

In August 2022, the U.S. Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) issued a requirement for the results of all research produced with taxpayer dollars to be made “immediately available to the American public” (EOP, 2022b). Beyond core expertise in ocean acoustics, expertise in data management and information technology is needed to make the vast amounts of acoustics data being acquired publicly available. Public access to data collected for a specific project or purpose will increase their value by supporting innovative science and research beyond their original purpose. Data collection is expensive and often requires both equipment and vessel time. Growing expertise in the infrastructure to support acoustic data dissemination and analysis will directly contribute to identifying patterns and trends in long-term ocean acoustics time series and educating the future workforce by supplying real-world data to classrooms and elevating the visibility of the value of ocean sound (Data Management subsection in Chapter 6).

STUDY TASK AND APPROACH

In 2022, ONR sponsored the National Academies to conduct a study that evaluated the state of ocean acoustics education and expertise, considering the large number of federal and international initiatives underway relating to the ocean environment. The study considered the state of ocean acoustics expertise across all areas of ocean science, including ecology, biology, oceanography, ocean engineering, and ocean energy. It was also charged to examine not only the future demand for ocean acousticians across all ocean disciplines but also the state of the field in embracing and incorporating new technologies related to observations, data archiving and accessibility, cooperative metadata resource hubs, machine learning (ML), and artificial intelligence (AI) applications. Box 1-1 presents the full Statement of Task.

The committee built upon reports and evaluations of different aspects of ocean acoustics research and education (COL, 2018; Hackerman et al., 1990; Lackie, 1997) to address the Statement of Task. In reviewing historical documents, the committee used their suggested actions or recommendations as a starting point for developing this report and its own recommendations (see Table 6-1) to address the support needed for ocean acoustics research and education and preparation and recruitment of a diverse workforce. Tables 1-1 and 1-2 provide a summary of the itemized actions and recommendations, categorical classification of the potential resolution (e.g., fiscal, infrastructure, outreach), the committee’s assessment of progress since the time of the original report, and its consensus on the current/future relevance of the actions or recommendations. As expected, these actions and recommendations were largely reflective of defense needs; however, the committee assessed current relevance across all sectors and applications related to ocean acoustics.

Next, the committee collected information on specific areas outlined in the Statement of Task. This included (1) a thorough review of the literature; (2) contracting a consultant to develop, distribute, and analyze an online questionnaire; (3) several public information-gathering panels; and (4) its own collective knowledge and experience.

BOX 1-1

Statement of Task

An ad hoc committee will assess the current and future state of ocean acoustics expertise required to realize the full value of ocean acoustics knowledge and capabilities across a diversity of fields and applications. This will be conducted through (1) an examination of ocean acoustics education in the United States; (2) assessment of the demand for acoustics expertise, as anticipated over the next decade; (3) identification of competencies required for undergraduate, graduate, and professional training programs that will be required to fulfill that demand; and (4) exploration of strategies to raise the profile of careers in ocean acoustics, including education, training, and workforce recruitment and retention. The report will include information on

- Academic institutions that offer courses in ocean acoustics or include ocean acoustics as a unit within related coursework.

- Public- and private-sector professional-level organizations that require expertise in ocean acoustics as part of their operations.

- Ocean acoustics workforce needs in key sectors/industries.

- Training programs currently available in these key regions.

- Examples of current ocean acoustics programs.

This information will be gathered by the committee as part of their assessment of the needs for ocean acoustics expertise, anticipated demand in the next decade, and potential needs for additional training opportunities. The committee will recommend resources required to support ocean acoustics research and education, and preparation and recruitment of a diverse workforce.

| 1997 Lackie Report Suggested Actions | Resolution Classification | Progress | Current Priorities/Relevance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Take actions to maintain the production of students receiving graduate education in acoustics, even if many of those receiving such education do not take jobs in Navy research and development (R&D). | Fiscal | 2 | Medium |

| 2 | Take public action to recognize the importance of ocean acoustics to the Navy by increasing funding, protecting the program from cuts, establishing research chairs and student awards, or other appropriate, high-visibility actions. | Outreach | 1 | High |

| 3 | Discuss the lack of support for ocean acoustics research with the directors of such agencies as the National Science Foundation, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the Department of Energy. These agencies have traditionally relied on the Office of Naval Research (ONR) to provide the people and tools needed for other acoustics applications. | Fiscal | 3 | High |

| 4 | Establish an ocean acoustics infrastructure fund to reduce the cost of doing ocean acoustics field work and manage at least some of the equipment purchased with these funds as national assets available to all users. | Fiscal, Infrastructure | 1a | Low |

| 5 | Establish an Ocean Acoustics Scientific Advisory Panel to engage the community in the process of formulating and overseeing the ocean acoustics research program. | Infrastructure | 3 | Medium |

| 6 | Make a serious effort to increase the average grant size and commit to more multiyear projects. | Fiscal | 3 | Medium |

| 7 | Integrate 6.1b and some 6.2c program management responsibilities in ocean acoustics and encourage joint academia-Navy laboratory/center 6.1 and 6.2 proposals in some areas. | Infrastructure | 2 | Low |

| 8 | Engage other Navy offices in discussions to improve the integration of ONR sponsored science and technology work with higher-level R&D programs that have major ocean acoustics components. | Infrastructure | 3 | Medium |

| 9 | Designate a limited number of academic institutions as Institutes of Naval Ocean Acoustics to serve as central sites through which ocean acoustics research would be administered. | Infrastructure | 0 | Medium |

| 10 | Establish a counterpart to the “ARL Project” focused entirely on ocean acoustics. | Infrastructure | 0 | None |

| 11 | Establish fellowship programs focused entirely on ocean acoustics. | Fiscal, Infrastructure | 4 | Medium |

| 12 | Establish an ocean acoustics summer internship program for undergraduates between their junior and senior years. | Infrastructure, Outreach | 0 | Medium |

| 13 | Use topical workshops to improve synergy between the Navy laboratories/centers and academia, to develop joint laboratory/academia research programs, and to better connect research with requirements. | Outreach | 2 | Medium |

| 14 | Use the foregoing mechanisms to increase the involvement of the community in planning broad, long-range programs and then execute these plans wherever possible. | Outreach | 2 | Low |

NOTE: Reflects committee assessment based on collective knowledge and information gained through the information-gathering panels in alignment with the Statement of Task. The Lackie (1997) report included both research and education, so not all suggested actions relate to this committee’s focus on education and training. Resolution classification relates to the mechanism for addressing and achieving a solution/resolution identified by the recommendation. Fiscal relates to funding availability and investment. Outreach relates to visibility, awareness, and value. Infrastructure relates to both physical and administrative infrastructure to support research and education. Progress was estimated based on a 0–4 scale, with 0 equating to no progress, 2 maintaining the status quo, and 4 indicating substantial progress. Current priority/relevance is assessed at None, Low, Medium, and High.

a Low for education; stronger marine tech education system (supporting discipline to ocean acoustics) is still needed.

b,c ONR budget activity code 6.1 is for basic research and 6.2 is for applied research.

SOURCE: Lackie (1997).

| 2018 COL Report Recommendations | Resolution Classification | Progress | Current Priorities/Relevance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The U.S. Navy should highlight the concerns raised in this study to the wider, federal ocean science community as they directly relate to growing risk to our overall national security. Mechanisms such as the interagency Ocean Policy Committee could be used to develop national efforts to reverse the trends regarding U.S. ocean scientific research preeminence. | Infrastructure, Outreach | 4 | High |

| 2 | The U.S. Navy should consider means to influence standard data collection and metrics across the federal government and among allied/partner nations to enable continual and consistent assessment of the indicators analyzed in the development of this report (and others). | Infrastructure | 0 | Low |

| 3 | The Department of Defense (DoD) should conduct theater-specific analyses of indicators and trends among allied/partner and competitor nations to evaluate and predict collective ocean-science-based knowledge advantages and disadvantages against theater-specific competitors. | Infrastructure | 0 | Low |

| 4 | DoD should coordinate with the Department of State to conduct a visa-based analysis of U.S. collegiate ocean science student and faculty migration statistics and patterns. | Infrastructure | 0 | Low |

NOTES: Categorical resolution classification, quarter-century progress, and contemporary priority/relevance information reflects committee assessment based on collective knowledge and information gained through the information-gathering panels in alignment with the Statement of Task. Resolution classification relates to the mechanism for addressing and achieving a solution/resolution identified by the recommendation. Fiscal relates to funding availability and investment. Outreach relates to visibility, awareness, and value. Infrastructure relates to both physical and administrative infrastructure to support research and education. Progress was estimated based on a 0–4 scale, with 0 equating to no progress, 2 maintaining the status quo, and 4 indicating substantial progress. Current priority/relevance is assessed at None, Low, Medium, and High.

SOURCE: COL (2018).

Education and training opportunities in the field of ocean acoustics and supporting disciplines have been available at a highly specialized level over the past 3–4 decades, and the committee devoted much thought to the need to expand these opportunities (before graduate school specialization) for the next generation of students, researchers, employees, and the public seeking to learn about the value, applications, methodologies, and technology of ocean acoustics.

The online survey, Ocean Acoustics Education and Expertise, was developed in consultation with Social Policy Research Associates (SPRA) to collect feedback from a variety of higher education institutions and workforce areas on the existing capacity to support the field of ocean acoustics and anticipated future needs. The survey was designed to reach a broad audience within the ocean acoustics community and help the committee understand the current state of education, needs for expertise, anticipated demand in the next decade, and needs for additional training opportunities.

The committee used academic and industry groups to reach a diverse group of respondents. The survey was distributed to individuals within academia, industry, government, and professional societies involved in ocean acoustics and related fields. Committee members promoted the survey at professional meetings and workshops, including the spring 2023 ASA meeting and 2023 Global Ocean Science Education Workshop, and recruited through their own networks to reach as wide and as diverse an audience as possible. The survey reached 200 individuals, of whom 61.5 percent completed or partially completed it. After the results were cleaned and analyzed, 110 unique responses were used to inform SPRA’s survey report (see Appendix B).

The survey was tailored to the following response categories: academia, workforce (with distinctions between industry and federal employees), and professional societies. The 110 responses included 59 academic respondents, 48 total workforce respondents (19 industry and 29 federal government), and three professional society respondents.

The survey was divided into five subsections: Background; State of Acoustics Education; Mentorships, Internships, Apprenticeships, & Competencies; Recruitment Strategies; and Future of Acoustics. More detailed results and analysis are provided in Chapters 3, 4, 5, and 6.

The survey was designed to reach a large portion of the ocean acoustics community, but completion was voluntary. It also allowed respondents to skip questions if they did not have specific information (e.g., specific student enrollment numbers) available. The results provided valuable insights and reached a broader portion of the ocean acoustics community than the committee would have been able to reach through other information-gathering means. However, the results may not be entirely reflective of the ocean acoustics community or the state of higher education and training due to the voluntary nature of responses, limitations in institutional data accessible to some respondents, and length. The survey was designed to be completed in approximately 20 minutes or less.

The committee also held several information-gathering panels and targeted discussions with individuals from academia, industry, and government sectors. These were an opportunity to invite speakers to share their personal expertise and engage in question-and-answer sessions around topics relating to the Statement of Task. The topics included the following:

- Workforce (Government, Academia, and Industry)

- Early-Career and Recent Graduates

- Higher Education and Training

- Outreach

- STEM Education

- Naval Training Programs

The committee did not include a detailed analysis or review of international programs during its information-gathering process because it fell outside the scope of this report. However, many international organizations that conduct work related to ocean acoustics could provide additional opportunities for training programs or workshops not covered in this report. Some examples include the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea Working Group on Fisheries Acoustics, Science and Technology, International Quiet Ocean Experiment, or, related to defense, the Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization and Centre for Maritime Research and Experimentation.

REPORT STRUCTURE

The report is organized to present the state of ocean acoustics education and expertise and anticipated needs related to the future workforce. Chapter 2 starts by providing a historical summary of ocean acoustics education; Chapter 3 offers an assessment of current education and training opportunities targeting acoustics, ocean acoustics, and supporting disciplines. Chapter 4 contains a compilation of the current and potential future workforce and employment landscape. Chapter 5 evaluates methods for increasing workforce diversity and provides examples of education and training strategies to attract students and retain professionals in the ocean acoustics career pipeline. Finally, Chapter 6 analyzes the gaps between education opportunities and workforce needs and presents the committee’s recommendations to support ocean acoustics research and education now and in the future.