A New Vision for High-Quality Preschool Curriculum (2024)

Chapter: 3 The Science of Early Learning and Brain Development

3

The Science of Early Learning and Brain Development

The neurobiology of learning and the powerful influences of the early environment on brain development are central considerations in planning effective preschool curriculum. The principle that there are sensitive periods during early childhood when the capacity for learning is enhanced has been well established in specific domains (language, visual) and is the focus of ongoing investigation in cognitive, social, and emotional domains (Werker & Hensch, 2015; Woodard & Pollack, 2020). Broadly, the existence of sensitive periods and related high neuroplasticity during the early years of life represent a window of opportunity for enhancing early learning, as specific skills and abilities are known to be absorbed or learned more readily during these periods. In turn, because learning is a cumulative process, enhanced early learning can lead to long-term learning benefits. In contrast, when opportunities for environmental stimulation and expected experiential inputs are missed, the early years can be a period of unique vulnerability and can lead to learning challenges at later developmental periods.

Moreover, children’s early learning depends on strong starting points as well as the experiences children have in their environments. Across cultures, infant studies show evidence of strong initial states—termed “core knowledge.” Studies indicate that core knowledge is universal across disparate cultures (e.g., Spelke, 2022; Spelke & Kinzler, 2007). Core knowledge domains are evolutionarily ancient, are shared with other species, and have continuity across the human lifespan. They include knowledge about objects and their physical actions, such as their continuity and contact constraints (Aguiar & Baillargeon, 1999; Leslie & Keeble, 1987; Spelke, 1990);

knowledge about agents and their goal-directed actions and intentions (Spelke et al., 1995; Stavans & Csibra, 2023; Woodward, 2009); knowledge about what number is approximate for all but the smallest sets (Carey, 2004; Carey & Barner, 2019; Dehaene, 1997); knowledge about geometry, which allows infants and young children to navigate based on the geometry of spaces and to represent shapes based on angle and side length (Cheng & Newcombe, 2005; Dehaene et al., 2006; Izard & Spelke, 2009; Newcombe & Huttenlocher, 2003); and core social cognition, which enables babies to represent others with whom they interact and their social group (Kinzler & Spelke, 2011; Kinzler et al., 2007; Spelke, 2022). Importantly, core knowledge systems are malleable, and children’s initial states change depending on their experiences. For example, as early as 3 months of age, infants show an own-race preference for faces, but this is based on their exposures and is not seen in infants who grow up in environments where they are exposed to other races (Bar-Haim et al., 2006; Kinzler & Spelke, 2011). Somewhat later, at 11 months, infants growing up in Latine or White families exhibit a bias to looking at minority group faces (Singarajah et al., 2017), which may reflect the preference for novelty outweighing the preference for familiarity (Aslin, 2007). In this way, children build on their core knowledge through their lived experiences, which occur within their sociocultural contexts (Gutiérrez & Rogoff, 2003; Gutiérrez et al., 2017).

This chapter briefly reviews the neurobiological and sociobehavioral research that shows the influence of early life experiences on early childhood development, including brain development, that can impact outcomes later in life. It then describes the science of early learning, detailing the multiplicity of ways children learn, from active exploration and observation of others to adults’ explicitly sharing knowledge with them. Content and skills typically shared by adults with children include domain-general skills—social-emotional learning and executive function—as well as domain-specific skills—language, literacy, and math learning. The chapter concludes with a discussion of the implications of the science of early childhood development and early learning for preschool curriculum development, including cultural and linguistic variations in learning opportunities and learning.

NEUROBIOLOGICAL AND SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL DEVELOPMENT

The early developmental period is recognized as the most important developmental phase of the lifespan, during which the young child’s experiences and exposures sculpt the brain to ready it for learning and positive adaptation. Building on these principles of neuroplasticity, the preschool period and preschool experiences may have a particularly important impact on developmental trajectories and provide opportunities to build strong

foundational skills more efficiently than is the case later in development. Thus, the preschool period is a window of opportunity for enhanced learning, and the neuroscience of sensitive periods can be used to inform the content, timing, and pedagogical focus of early educational curricula. In other words, the neuroscience of sensitive periods provides a roadmap for the “what,” “when,” and “how” of early curricula.

Experiences across environmental contexts play a significant role in early development. As summarized in a recent report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Vibrant and Healthy Kids:

A large body of recent research provides insights into the mechanisms by which early adversity in the lives of young children and their families can change the timing of sensitive periods of brain and other organ system development and impact the “plasticity” of developmental processes [. . .] a wave of neurobiological studies in model systems and humans found that responses to pre- and postnatal early life stress are rooted in genetic and environmental interactions that can result in altered molecular and cellular development that impacts the assembly of circuits during sensitive periods of development. The demonstration that certain systems involved in cognitive and emotional development are more sensitive to early disturbances that activate stress response networks, such as the frontal cortex, hippo-campus, amygdala, and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, provided a basis for both short- and long-term functional consequences of early life stress. New research has clarified that altered nutrition, exposure to environmental chemicals, and chronic stress during specific times of development can lead to functional biological changes that predispose individuals to manifest diseases and/or experience altered physical, social-emotional, and cognitive functions later in life. (2019, p. 7)

This section reviews key features of early development with particular relevance for fostering positive outcomes for preschool-aged children, including the caregiving environment, the presence of stress, and access to resources.

Caregiving Environment

The early caregiving environment—including familial relationships; safe, stable, nurturing relationships and environments; healthy living conditions; economic security; nutrition and food security; neighborhood and community conditions; housing; and environmental exposures—is crucial for long-term development (National Academies, 2019). Importantly, children learn optimally when they feel safe and secure in their home and neighborhood environment before arriving at preschool. Critical for this sense of basic security and readiness to learn and thrive is the presence of at least one nurturing and reliable primary caregiver upon whom a child

can rely for protection and necessary physical and emotional support and assistance (Brown et al., 2020). This is necessary under all circumstances but particularly critical in environments with high rates of early adversity, where buffering factors are of paramount importance to ensuring positive developmental trajectories (Brown et al., 2020).

Certain supports within the caregiving environment are also necessary to enable young children to benefit optimally from learning experiences. Along this line, one key prerequisite is regular daily rhythms, central to which is the opportunity for restful sleep, which has been shown to be a necessary precondition for optimizing learning and memory in early childhood, as well as throughout life (Spencer et al., 2017). A related finding is that unpredictable parenting signals (e.g., parents behaving erratically) are associated with poorer executive function in middle childhood (Davis et al., 2022; Granger et al., 2021), a phenomenon also seen in animal models, where alterations in the development of subserving brain circuitry have been demonstrated (Davis et al., 2022). The basic forms of adversity in early childhood that have been shown to impact brain development and learning negatively are deprivation, threat, and unpredictability; therefore, these key domains need to be addressed prior to school entry if learning is to be optimized (McLaughlin & Sheridan, 2016). Importantly, when children live in chaotic households and/or neighborhoods that are impoverished and have high rates of violent crime, their basic sense of security and regularity is undermined. More obvious is the need for adequate nutrition to maintain energy, focus, and alertness. These prerequisites within the caregiving environment—sleep, predictability, and nutrition—are often either overlooked or assumed to be available to all children. In fact, many children do not have these foundational biological supports, a social reality highly relevant, and representing a major impediment, to many developing children’s ability to learn.

Early Exposure to Stress

Related to these prerequisites of security, safety, adequate protection, and necessary resources, studies have demonstrated that children exposed to trauma and chronic stress have physiological responses that impact brain development and functioning in ways that interfere with the learning process. High levels of chronic stress impact both brain and behavior in ways that put the child on “high alert” for ongoing and expected threats, which of necessity diverts their attention from the learning process and alters cognitive processes that allow consolidation of memory, executive function, and other elements essential to learning (Gunnar, 2020). These conditions elevate circulating stress hormones, notably cortisol, with receptors in brain regions key to learning and memory. Chronic exposure to elevated stress hormones without external buffers, such as supportive caregivers, has been shown to alter brain development and related cognitive capacities

negatively over time (Lupien et al., 2007). Accordingly, children with these exposures may require additional supports before and in concert with their entry into preschool environments to facilitate their development of the basic prerequisites for their ability to learn.

In addition to psychosocial stressors, children living in low-resource environments also have greater exposure to environmental toxins (National Academies, 2023). It has become clear over the past several decades that exposures to low levels of a growing list of environmental toxins found in air and water contribute to poor outcomes including low birth weight, shorter gestation, and intellectual disability, as well as increased risk for psychopathology (Lanphear, 2015; National Academies, 2023). The detrimental effects of these exposures in utero and in early childhood is underscored by the fact that the blood–brain barrier is more permeable during this period and that growing organs are more susceptible to the negative effects of toxins. Based on these facts, these exposures, which are ubiquitous but more common in underresourced neighborhoods, pose a major threat to the young child’s ability to learn (Kumar et al., 2023).

Minoritized children and families face structural inequities, unequal treatment, and acts of discrimination and racism that add to the cumulative burden of stress and require focused attention (Shonkoff et al., 2021). Researchers have recently turned their attention to the unique impacts of racism on the foundations of physical and mental health. Studies of residential segregation by race as they affect risk exposures and health have, for example, linked poorer pregnancy outcomes among women of color to disproportionate exposures to environmental toxins (Miranda et al., 2009). At the family level, parents’ self-reported experiences of discrimination have been associated with their children’s social and emotional problems, as well as with increased levels of cortisol and proinflammatory cytokines—indicators of disrupted stress-response systems (Bécares et al., 2015; Condon et al., 2019; Gassman-Pines, 2015, as cited in Shonkoff et al., 2021, p. 123). And Black children are three times more likely than their White counterparts to lose their mother by age 10 (Umberson et al., 2017). These are among the experiences of adversity arising from racism, and their impacts, that minoritized children bring with them into their early childhood settings. To facilitate learning for these children, then, early educators need to be sensitized to and prepared to buffer these experiences. Toward this end, knowledge of trauma-informed approaches is a critical component of the professional preparation of early educators (de la Osa et al., 2024).

Access to Resources

Related to these basic prerequisites for early learning, neurodevelopmental research has shown that family socioeconomic status, particularly poverty, is negatively associated with differences in brain structure

and function in multiple domains, including language, cognition, executive function, memory, and social-emotional processes (e.g., Brooks-Gunn & Duncan, 1997; Hackman et al., 2015; Noble et al., 2007; Stevens et al., 2009). Moreover, experiences that include those discussed above, as well as differences in opportunities to learn, have been found to account for a significant portion of the relationship between socioeconomic status and learning and development (Brooks-Gunn & Duncan, 1997; Capron & Duyme, 1989; Duncan et al., 1994; Jimerson et al., 2000; Noble et al., 2007; Schiff et al., 1982). Recent data from the Child Opportunity Index, which ranks neighborhoods on multiple dimensions of opportunity, such as access to early childhood centers and healthy food outlets, reveal that a majority of Black, Latine, and Native American children reside in low- or very low–opportunity communities, compared with one in five White and Asian children (Acevedo-Garcia et al., 2020). In addition, there is increasing evidence that exposure to “green space” and outdoor spaces are important for multiple developmental domains, including emotional well-being (McCormick, 2017).

HOW CHILDREN LEARN: THE SCIENCE OF EARLY LEARNING

Children learn in a multiplicity of ways—through active exploration and play; through observation of others, notably older children and adults; and through adults’ explicitly sharing knowledge with them. This section reviews each of these types of learning in turn.

While these three types of learning occur across all cultures, their prevalence differs depending on cultural context. For example, children from U.S.–Mexican heritage families in which mothers had experience with Indigenous ways were found to be much more likely to learn from observing a toy construction activity directed to another child than were Mexican heritage children whose mothers had extensive experience going to Western schools (Silva et al., 2010). Further, as discussed later in this chapter in the section on language learning, children learn through child-directed speech, as well as through listening to adult conversations, with the prevalence of these learning opportunities differing depending on cultural context (e.g., Casillas et al., 2020; Shneidman & Goldin-Meadow, 2012).

Exploration and Play

Exploration and play have long been recognized as universal aspects of childhood, and they are found in every culture that has been studied (e.g., Hughes, 1999; see Vandermaas-Peeler, 2002, for review). At the same time, play varies across cultural contexts in multiple ways, including the nature of play activities children engage in, reflecting the diversity of children’s

experiences and the materials that are available, the degree to which adults and older children are involved in the play, and the nature of their involvement (e.g., Haight et al., 1999; Roopnarine et al., 1998; Vandermaas-Peeler, 2002, for review). There is also cultural variation in the degree to which play is viewed as being tied to learning or as differing from learning, which is viewed as linked to work more directly (Metaferia et al., 2021).

Environmental factors can also affect the extent to which children have access to safe environments for play. As noted in the 2023 National Academies report Closing the Opportunity Gap for Young Children, children from families with lower incomes and children from minoritized populations are more likely to live in environments where there is a risk of exposure to environmental contaminants than are children from other backgrounds. In addition, children in disadvantaged neighborhoods are more likely to live in environments where there is poor urban planning, increased risk of injury from roadways and traffic, and higher rates of neighborhood violence (National Academies, 2023).

Various constructivist theorists have highlighted the importance of play and exploration in the development of children’s thinking, language, and social skills (e.g., Bruner, 1983; Piaget, 1962; Vygotsky, 1967, 1978). These theorists posit that the information children gain through play and exploration is not just received passively but rather is integrated actively with their prior concepts and ideas (see Narayan et al., 2013, for review). They also characterize play as a joyful activity with an important role in development and learning. For example, Bruner (1983) characterized play as a joyful way of solving problems and as a testbed for trying out and combining ideas and skills without worrying about consequences of failing to achieve a goal. Dewey (1910) emphasized the importance of a playful attitude toward the process of learning, coupled with the serious attitude of work toward goals of learning. These theories differ in the emphasis they place on adults and older children as promoting children’s learning through explorations and play. Piaget (1970), for example, focused on the role of the child’s own explorations of the world, characterizing the child as a little scientist who actively gathers information by exploring the world. In contrast, Vygotsky, Dewey, and Bruner considered the role of adults and older children in supporting children’s development during play and other activities via the provision of materials and through language interactions (e.g., Bruner, 1983; Dewey, 1910; Vygotsky, 1967, 1978). Notably, Vygotsky (1978) highlighted the role of adults in extending children’s learning by providing scaffolding that allows them to extend their learning into their zone of proximal development.

Contemporary researchers have built on and extended the work of these theorists. A growing body of research shows that children engage in and learn from active exploration as early as infancy. For example, as early

as 11 months of age, babies learned more and engaged in more relevant exploratory behaviors when objects violated their expectations than from nearly identical experiences that were consistent with their expectations (Stahl & Feigenson, 2015). Follow-up studies replicated these findings and showed that infants explored more after an event that violated their expectations (e.g., an object that appeared to float) because they sought an explanation for why objects behaved in this manner (Perez & Feigenson, 2022).

Studies involving preschool children provide compelling evidence that children learn from exploration and explore more than adults even when they know that exploration carries risks (e.g., Gopnik, 2012, 2020; Liquin & Gopnik, 2022; Schulz, 2012; Xu & Kushnir, 2013). For example, in a task that involved discovering how stimuli were classified differently, Liquin & Gopnik (2022) found that preschool children were more likely to explore than adults, and children’s propensity to explore enhanced their success on this task. Another study showed that 4- to 6-years-olds learned more when active exploration was encouraged and when adults did not fill in all the gaps in children’s knowledge. In one study, Bonawitz et al. (2011) gave preschool children (48–72 months; mean age 58 months) a novel toy with four different functions. Children were randomized into one of four conditions that varied in terms of the pedagogical support the adult provided. Two critical conditions were the pedagogical condition, where an adult showed them one function of the toy (that it squeaked) and a baseline condition in which the adult merely gave them the toy without demonstrating any of its functions. Strikingly, the children discovered significantly more of the functions of the toy in the nonpedagogical baseline condition (M = 4.0) than in the pedagogical condition (M = 5.3). Moreover, children played with the toy significantly longer in the nonpedagogical condition.

In another study, 4- to 5- year-old children were presented with finding out the “secret of shapes” (e.g., triangles), and were randomly assigned to one of three conditions. In the didactic, pedagogical condition the adult taught the attributes of triangles directly; in the guided play condition the child was encouraged to do the discovering with teacher scaffolding; and in the free play condition, children were simply given the shapes to play with. Strikingly, children learned more about the defining features of shapes when they were in the guided play condition compared with both the direct instruction and the free play conditions; this was true both immediately after the training and 1 week later.

Considered together, these findings highlight the benefits of guided play in supporting children’s learning and persistence. Guided play provides the child with agency to test their nascent theories about the world. It also provides them with adult-guided situations and language that support their learning (Hirsh-Pasek et al., 2020). Contemporary researchers, aligned

with the Vygotskian view, emphasize the role of guided play in supporting the child’s active exploration of their environment and their learning. Research findings indicate that guided play supports not only the growth of content knowledge (the “what” of learning) but also the learning process (the “how” of learning), which together enable them to pursue their questions, problem solve, and collaborate. With the exponential growth of information in contemporary society, it is important that children’s experiences help them gain content knowledge, confidence, curiosity, creativity, communication, and collaborative skills—known as the 6 Cs; each is valued in the 21st century (Hirsh-Pasek et al., 2020).

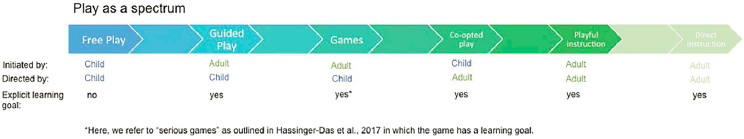

Aligned with research and theory highlighting the connection of play to children’s learning, preschool teachers rate children who display curiosity as having higher learning ability/skills; and teachers’ ratings of children’s curiosity in preschool are associated with children’s achievement levels at kindergarten entry (Shah et al., 2018). However, despite these documented benefits of exploration and play, preschool environments vary in terms of whether exploration and question asking are encouraged or discouraged in favor of more structured activities that emphasize correct answers and adults providing children with information (Reid & Kagan, 2022). This may be linked to the belief that play and learning are separate, a false dichotomy discussed in Chapter 4. As pointed out by Zosh et al. (2018), there are many different kinds of play, and failure to recognize the nuanced spectrum of types of play can lead to confusion about how play relates to and supports learning. Play ranges from adult-directed play activities, in which the adult has a learning goal in mind; to guided play, in which the adult gives the child agency but provides scaffolding and guidance with a learning goal in mind; to free play, in which the child both initiates and constructs play without a specific learning goal (Zosh et al., 2018). Zosh et al. (2018) point out that play can be characterized by three attributes: the level of adult involvement, the extent to which the child creates the play, and whether a learning goal is present (Figure 3-1).

SOURCE: Zosh et al., 2018.

Hirsh-Pasek and colleagues propose that guided play provides a sweet spot for supporting children’s learning, as well as their curiosity, creativity, and collaborative skills (e.g., Hirsh-Pasek et al., 2008, 2020, 2022; Zosh et al., 2018). In guided play, the teacher plays the role of facilitator, which allows for intentional learning goals that can be tuned to the child’s current skill levels. At the same time, the light-touch hand of the teacher in guided play activities provides the child with agency, which is positively associated with academic outcomes and interests (e.g., Bruner, 1983; Hirsh-Pasek et al., 2020, 2022). For example, one study examined parents’ use of spatial language when playing with their 4-year-old children in three conditions—(1) free play with blocks, (2) guided play with blocks with a goal of building a particular structure, and (3) play with a preassembled structure (Ferrara et al., 2011). Parents in the guided play condition produced more spatial language than those in the free play or preassembled conditions. This finding is important because spatial language supports children’s spatial thinking, which in turn predicts success in the disciplines of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (e.g., Casasola et al., 2020; Hawes & Ansari, 2020; Mix et al., 2016, 2021; Pruden et al., 2011; Wai et al., 2009).

Related to these findings, pretend play and guided play are associated with oral language and literacy outcomes, likely because the language in which children engage during play is complex and contains rich vocabulary, including many mental-state verbs (e.g., Bruner, 1982; Dickinson & Tabors, 2001; Pellegrini & Galda, 1990; Roskos & Christie, 2001; Toub et al., 2018). Further, play activities support knowledge of mathematical language and thinking. Notably, play with a variety of materials provides opportunities to think about spatial relationships and patterns, either imagined or built; to compare magnitudes and shapes; and to enumerate sets (Eason et al., 2021, 2022; Fisher et al., 2013; Ramani & Siegler, 2008; Seo & Ginsburg, 2004; Siegler & Ramani, 2008).

While play-based learning is increasingly emphasized in research and practice in Western Euro-American contexts, a rich literature documents differences in the nature of play, the involvement of parents in play, and the amount of play children engage in depending on culture (see Vandermaas-Peeler, 2002, for review). Using three contrasting examples, Gaskins et al. (2007) highlight the fact that play is socially constructive and that adults’ roles in children’s play depend on culture. Whereas urban, educated American and Taiwanese adults cultivate children’s pretend play, in Liberia, the Kpelle, who are subsistence horticulturists, accept but do not participate in children’s play, as they need to conserve their time and energy to provide food and maintain their own strength. Instead, other children, including older children, are the playmates of younger children. Finally, in the Yucatec-Mayan culture, where people live in subsistence farming communities, development is seen as the unfolding of one’s inner abilities

and character. Consistent with this view, play is viewed as a distraction for children when they cannot help. Play still occurs, with older children taking the lead in pretend play, which typically involves pretending to do the work of adults rather than fantasy play. Additionally, the peak of pretend play in Yucatec-Mayan children is between ages 6 and 8, much later than the 3- to 6-year-old peak in Euro-American families. Rather than encouraging play, in the Yucatec-Mayan culture, children are encouraged to observe and work alongside adults in their community, as their work can eventually contribute to the overall productivity of the society. These cultural differences serve to illustrate the sociocultural nature of play.

Despite these cultural differences, the preschool landscape around the globe is currently undergoing rapid change, with many countries embracing play-based early education curricula. These changes are not without challenges, and they often mismatch with teacher and parent beliefs and lead to inequities; furthermore, professional development for teachers and large student–teacher ratios make these changes challenging to implement (Gupta, 2011; Yee et al., 2022). For example, in India, play-based private schools are equated with developmentally appropriate practices. Importantly, Gupta questions the appropriateness of Western, play-based approaches within a culture that prioritizes examination scores for access to higher education and advocates for approaches to early childhood education that emerge from Indian cultural values. Gupta (2011) records a teacher’s statement that “it rains so children can play in the water,” which connects a child-centered approach to the scarcity of water and the spirituality of the Monsoon season. In Korea, the revised Nuri curriculum (2019) put a heavy emphasis on free play, which has led to confusion among teachers about their role in supporting children’s learning (Lee et al., 2023). The lack of professional development around play is a factor in this confusion, and the emphasis on free play is at odds with research findings showing that guided play is more conducive to supporting many learning goals.

The studies discussed above highlight the importance of considering play in a culturally responsive manner, not as something in which all children engage in a uniform manner. Viewed in this way, children’s play has the potential to contribute to the cultural relevance of early education, as child-initiated play reflects children’s cultural experiences and how they see themselves within the larger society, providing teachers with an important lens into children’s lived experiences (Adair & Doucet, 2014). Moreover, children’s play provides teachers with a way to engage in guided play, enabling the teacher to build on children’s interests and skills, which, as we have discussed, may be one of the most effective ways to support learning.

A 2022 study involving interviews with 31 early childhood experts from different fields provides some relevant information with respect to play in early childhood education contexts that serve children from

different demographic backgrounds (Reid & Kagan, 2022). The experts were broadly supportive of the importance of play in early childhood curricula and, relatedly, were supportive of autonomy-granting approaches that give young children a voice in how they learn. Their support for this kind of approach recognizes the importance of children’s interests, curiosity, and explorations in the learning process and aligns with the research base. Nonetheless, the experts disagreed about the amount and nature of play that best supports children’s learning. Roughly half called for more play in curricula, whereas others noted that play-based approaches have gone too far in some schools. A potential explanation for disagreements about the role of play in early childhood curricula may be the cultural differences in how play is valued and practiced, as discussed previously.

Many of the experts interviewed by Reid & Kagan (2022) also expressed the belief that the amount of play children experience varies by the socioeconomic status of the children in the classroom, such that children from a background of lower socioeconomic status experience less play. Consistent with this belief, Adair & Colegrove (2021) provide evidence that there is “segregation by experience” in educational settings, such that young children in classrooms characterized by higher socioeconomic status have more opportunities to be agents in their learning and are provided with more opportunities to carry out explorations of their world compared with children in classrooms characterized by lower socioeconomic status, who are disproportionately children of color. Instead, young children of color are more often required to sit with their legs folded and hands placed together in silence, not because they need to attend to pedagogical content but for the purpose of practicing valued behaviors (Adair & Colegrove, 2021).

Similarly, an influential paper utilizing two waves of the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Class data (1998 and 2011) reports evidence that, of the two, kindergarten was more like first grade (more structured with less play) in the 2011 cohort, influenced by the No Child Left Behind Act and increased accountability and testing. Bassok et al. (2016) found that this was more starkly the case in settings serving children eligible for free or reduced-price lunch or children who were non-White (Bassok et al., 2016). For example, kindergarten teachers serving a larger percentage of children eligible for free or reduced-price lunch (in the highest quartile of representation of this group) were significantly more likely to endorse the importance of children’s knowing the alphabet at the time of kindergarten entry than was the case for kindergarten teachers serving students from backgrounds of higher socioeconomic status (51% versus 34%, respectively). These beliefs, whether implicit or explicit, are likely to have downstream consequences in terms of the nature of the pedagogy and curricula adopted in different early childhood settings, resulting in inequities in early learning opportunities.

The focus on more direct pedagogy and basic skills in classrooms serving children of lower socioeconomic status, racially minoritized, and immigrant backgrounds stems from deficit models, which incorporate the belief that minoritized children need direct instruction to build basic academic skills (e.g., vocabulary, letter recognition, counting) in order to narrow achievement gaps. Moreover, inequities in agentic learning stem from views about what children from different groups can handle, based, for example, on ideas about a “word gap” in children of Latine immigrants (Adair et al., 2017). When shown videos of Latine children engaging in agentic learning, teachers and school administrators said these practices are valuable but would not work in their classrooms because their students lacked vocabulary knowledge necessary for these practices to work. Moreover, children who viewed the videos were consistent in their evaluations of the children in the videos as being bad, not learning, being too noisy, and not listening to their teachers. While well meaning, limiting children’s agency in early education contexts based on perceived shortcomings denies children the kinds of experiences they need to build advanced language and thinking skills, as well as skills necessary for pursuing learning in which they are interested and collaborating and conversing with other children. Differential access to autonomy-granting, play-based pedagogy in early education is potentially harmful and is typically rooted in stereotypes about weaknesses of children and their families instead of being attributed to systemic factors that contribute to group differences (Adair, 2015; Adair & Colegrove, 2021; Adair et al., 2017; National Academies, 2023).

Young children need to gain both basic skills and higher-order thinking skills and be afforded the opportunities to acquire these skills in early education settings. Focusing on basic skills through direct instruction to the exclusion of agentic play-based activities may have unintended negative consequences because such gains have been found to fade over time (Bailey et al., 2016, 2017, 2020). In contrast, instruction that includes more play-based activities designed to foster exploration, curiosity, complex language skills, and higher-order thinking (e.g., acting out child-created narratives; exploring the conditions that lead plants to grow at different rates) are associated with positive long-term effects on children’s learning, as well as on their learning dispositions (e.g., Frausel et al., 2020, 2021). Thus, differences in pedagogical approaches that are related to biased perceptions about children’s sociocultural and linguistic backgrounds may be harmful, as they are likely to contribute to the very disparities in achievement they are intended to close.

A shortcoming of the current research base examining the prevalence and benefits of play and exploration is that play-based curricula and learning have not been examined systematically in early education settings of different types, and in settings that serve children from differing cultural

and socioeconomic backgrounds. While existing research suggests that there is a lack of equity in play-based approaches to learning in early education settings, more research is needed to confirm that this is the case and if so, to understand why this is happening. Further, research is needed to examine the benefits of play-based learning for children from different backgrounds. An essential step in addressing these gaps is conducting systematic research on children’s experience with agentic learning in early education settings serving children from diverse backgrounds, and studying the benefits of this approach for children’s learning as well as for culturally affirming practices that foster the belonging of children and families. In view of evidence from the science of learning, it is important that all children are provided with engaging, agentic learning experiences. With content knowledge exploding exponentially, educational approaches that support not only the “what” but the “how” of learning are of increasing importance. Children need to learn how to gain new knowledge, how to find answers to their questions, how to problem solve, how to communicate their ideas, and how to collaborate. These active, agentic, and playful approaches to learning, when implemented well, can serve to nurture children’s excitement about learning.

Observation of Others

Beginning with Bandura’s (1977) pioneering work on social learning, observational learning and imitation have been important for development and learning. Bandura posited that children observe and imitate role models and that this kind of learning requires attention, memory, reproduction, and motivation. More recent research has shown that humans, beginning in infancy, are astute observational learners. As early as 14 months of age, children engage in “overimitation,” highlighting their sensitivity to the culture they experience. For example, when they see an adult turn a light on by bending forward from the waist and touching a panel with their head, they imitate this behavior (Meltzoff, 1988). Although it would have been easier and less awkward to turn on the light with their hands, the infants turned on the light with their heads, imitating not only the goal but the means by which the adult turned the light on. Additionally, findings show that infants do not imitate what they perceive to be accidental behaviors or actions carried out by inanimate devices, but rather imitate intentional behaviors, even when those behaviors fail to achieve the intended goal (Carpenter et al., 1998; Meltzoff, 1995). In other words, children imitate the intention of the agent as well as the means by which they achieved their goal. Moreover, as early as the second year of life, children are more likely to imitate the actions of a linguistic ingroup-member than an to imitate an agent who speaks a foreign language (Buttelmann et al., 2013; Howard et al., 2015). Preschool children are also less likely to imitate an onscreen robot than an

onscreen human agent (Sommer et al., 2021). The proclivity of humans to imitate other humans, particularly members of their ingroup, represents a powerful way in which culture is shared intergenerationally. Thus, observation and imitation contribute to the accumulation and growth of knowledge across generations (e.g., Tomasello, 2020; Tomasello et al., 1993).

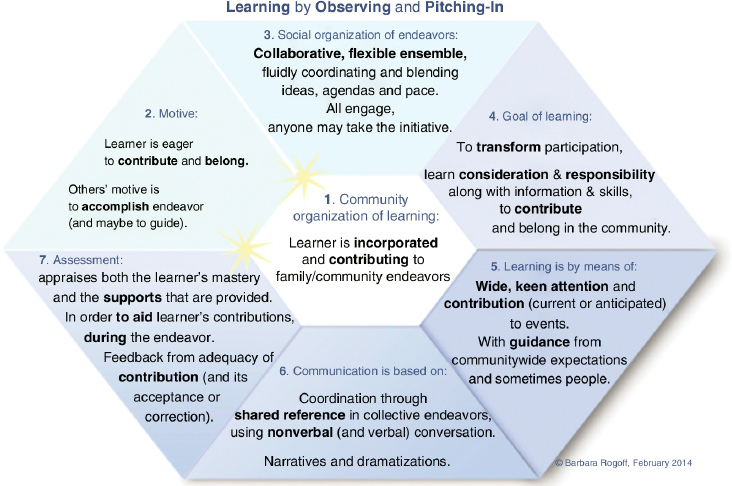

Building on findings showing that young children are astute cultural learners, Rogoff et al. (2015) studied the learning behaviors of children in Indigenous American communities, documenting differences in the learning behaviors and experiences of children growing up in different cultural contexts. Their Learning by Observing and Pitching In (LOPI) model characterizes a kind of learning that is common in, but not exclusive to, Indigenous American communities (Rogoff et al., 2015; Figure 3-2). LOPI consists of seven related facets, with the central facet being that the learner is incorporated in, and contributing to, meaningful family and community endeavors. LOPI involves wide-lens observing and listening-in on mature, purposive adult activities and conversations, being guided by members of the community to contribute meaningfully to communal goals and cultural activities, which increases their sense of belonging. Building on the LOPI model, Bang et al. (2015) highlight the more-than-human ecological interactions of Menominee Indian communities in Wisconsin, extending the

SOURCE: Rogoff et al., 2015.

LOPI model to include human–nature as well as human–human interactions (e.g., extending component 5 of the LOPI model [see Figure 3-2] to include wide-lens attention to human interactions with animals, plants, and nonanimate natural kinds, such as water).

The LOPI model is concordant with basic research findings highlighting the early sensitivity of children to the purposeful behaviors of adults around them and their selective imitation of their behaviors. Importantly, as pointed out by Rogoff et al. (2015), LOPI is deeply embedded in the cultures of Indigenous American communities and is consistent with many other practices and values of these communities.

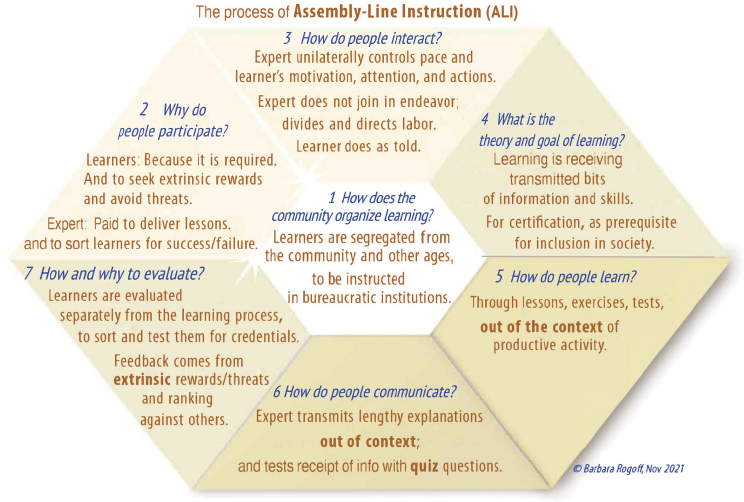

Rogoff et al. (2015) contrast LOPI learning to Assembly Line Instruction (ASI; Figure 3-3). ASI typically involves providing instruction outside of the context of adult activities, often at school (Rogoff et al., 2015). As pointed out by Pellegrini (2009), the type of instruction detailed in the ASI model is relatively recent and is associated with industrialized societies.

The careful work of these researchers shows that the ways children learn, as well as what they learn, are deeply connected to their cultural contexts. These findings hold important implications for early childhood education, as the kinds of learning that children experience may be very different from what they experience in their homes and communities.

SOURCE: Rogoff & Mejía-Arauz, 2022.

Sharing Knowledge Through Verbal Exchanges

Much of what children know and learn is influenced by the transmission of knowledge across generations. Indeed, the uniqueness of human cognition, including the human ability to innovate, depends on this intergenerational sharing, referred to as the “ratchet effect” (e.g., Tennie et al., 2009). Sharing knowledge with children occurs in a variety of ways, including via language, or “learning from testimony” (see Harris et al., 2018). This sharing occurs for multiple kinds of information but is particularly important for types of knowledge that are not accessible to children through their own explorations or firsthand observations. These include, for example, information about distant countries, historical events, microscopic entities, and the solar system (e.g., Harris, 2012; Harris et al., 2018).

Aligned with the views of constructivist theorists, young children are active participants in this sharing. That is, they do not just passively accept information that others share with them. Instead, they evaluate new information with respect to their preexisting knowledge and curate information based on whether the informant is credible (see Harris et al., 2018, for review). Koenig & Echols (2003) found that as early as 16 months of age, children are sensitive to the credibility of an informant—for example, looking longer at an informant that labeled a dog as a “cup.” Similarly, 3- and 4-year-olds who were able to identify accurate and inaccurate labelers of objects showed trust in novel information provided by the accurate labeler (Koenig et al., 2004). In three meta-analyses, Tong et al. (2020) found that 3- to 6-year-old children trust the testimony of credible informants as well as the testimony of informants with more positive social characteristics (e.g., information provided by characters they perceive as nicer). In addition, they identified an important developmental change between ages 3 and 4 years: 4-years-olds weigh informants’ knowledge more heavily than their social characteristics, while 3-year-olds do not, possibly because of increases in theory of mind at age 4 (Tong et al., 2020).

Children’s Learning During the Preschool Years

This section briefly considers the kinds of skills children begin to acquire in the early years of life, including skills considered to be domain general and those considered to be domain specific. “Domain-general skills” include social-emotional learning and executive functioning skills. They also include language skills, which of course support communication and literacy, but provide tools for understanding relational concepts, (e.g., de Villiers & de Villiers, 2014; Gentner, 2016). “Domain-specific skills,” such as numerical thinking and understanding the physical world, begin with core sensitivities that are present from birth onward, but require acquisition

of knowledge (e.g., the count system) to transcend these starting points (e.g., Carey & Barner, 2019; Spelke & Kinzler, 2007). Importantly, learning in all of these domains predicts academic learning as well as important life outcomes, including health, income, and life satisfaction (e.g., Diamond, 2016; Moffitt et al., 2011; Ritchie & Bates, 2013; Watts et al., 2014).

As reviewed in Chapters 2 and 4, early childhood curricula can be broadly separated into comprehensive or whole-child curricula or focused, domain-specific curricula. Most multidomain preschool curricula address the domains of literacy/language, mathematics, science, social-emotional learning, and the arts. Importantly, during the preschool years, instructional activities often support multiple domains of learning. To take just one example, experiencing a book about sharing may support children’s social-emotional learning, math learning, and language and literacy development. In the sections that follow, we provide a brief overview of research on young children’s learning in key domains that are included in early education curricula, including social-emotional learning, executive function, language/literacy learning, and math learning.

Social-Emotional Development as Foundational for Learning

Decades of research have made clear that early emotional development—evidenced by the ability to identify and express one’s own emotional states, accurately recognize emotions expressed by others, and adaptively regulate intense emotions—is key to adaptive success in childhood and later life (National Research Council [NRC] & Institute of Medicine [IOM], 2000). Evidence also shows that these skills can be fostered and enhanced in early childhood learning environments (Denham, 2019). These features of emotional competence—emotion knowledge; understanding of the causes, consequences, and display rules of an emotion (Izard et al., 2011); and the ability to regulate emotion—then foster the development of social skills. Together, social-emotional skills facilitate meaningful interpersonal relationships and interactions characterized by prosocial behavior, empathy, and interpersonal connectedness with peers. It also has become clear that these social-emotional competencies set the stage for enhanced learning trajectories, a finding validated by a meta-analysis showing that interventions focused on social-emotional learning increased academic performance by 11 percentile points (Durlak et al., 2011). Those children with better social-emotional skills also showed reduced conduct problems and emotional distress, more prosocial behaviors, and more positive social attitudes toward self and others. In keeping with this finding, greater social-emotional competence has been associated with less psychopathology and more adaptive and academic success broadly within early childhood and beyond (Finlon et al., 2015).

At preschool age or earlier, children are able to infer basic emotions from expressions and situations (Bell et al., 2019; Denham, 2019). Increased early exposure to language has been shown to support emotional development (Lindquist et al., 2015). More broadly, a supportive relationship with a primary caregiver has been established as foundational for social-emotional development (National Academies, 2023). The supportive primary caregiver may provide emotion language to aid in emotion knowledge. Perhaps more important, the caregiver serves as the child’s external emotion regulator and emotion coach (also referred to as coregulation in infancy), and models and validates the appropriate expression of emotion in context. Further, evidence indicates that greater language skills support the young child’s ability to regulate emotion autonomously instead of relying on caregiver-supported regulation (Eisenberg et al., 2005; NRC & IOM, 2000). Accordingly, many early childhood interventions designed for the prevention of later psychopathology target this element of the child–caregiver relationship and facilitate the child’s emotion knowledge and competence (Bohlmann et al., 2015; Salmon et al., 2016; Shonkoff & Fisher, 2013). Furthermore, the importance of this focus on social-emotional development for early education is underscored by how predictive these skills are of later academic achievement. Thus, the preschool teacher (through curriculum and teacher–child relationship dynamics) can also play an important role in facilitating social-emotional development and should be an important focus of curriculum development and prioritization.

In summary, early social-emotional development represents foundational skills that are necessary for healthy learning trajectories. Furthermore, these skills are important beyond their role as foundational for cognitive development, having interactive effects across developmental domains: cognition and emotion are dynamic developmental processes, with the maturation of one serving as a catalyst for enhancement of higher-level skills in the other (Bell & Wolfe, 2004; Bell et al., 2019; Davidson et al., 2014).

Executive Function as Foundational for Learning

Executive functioning skills include working memory, inhibitory control, attention shifting, and cognitive flexibility (Miyake et al., 2000). These skills develop rapidly during the preschool years, with their development being related to the maturation of the prefrontal cortex (Diamond, 2020). Prior to about 4.5 years of age, the various components of executive functioning load on one factor and are less differentiated than at older ages (e.g., Wiebe et al., 2011). Early executive functioning and self-regulation skills are related to concurrent and future academic achievement (e.g., Alloway & Alloway, 2010; Blair, 2016; Bull et al., 2008; Schmidt et al., 2022; Zelazo et al., 1997).

Executive functioning skills are related to children’s socioeconomic background by 54 months of age, and this relation is stable across development (Hackman et al., 2015; Lawson et al., 2018). Moreover, executive functioning skills partially mediate the relation of socioeconomic status to academic achievement in young children (Lawson & Farah, 2017; Waters et al., 2021). Additionally, family stress and family investment are related—that is, the emotional support (e.g., warmth) and cognitive stimulation families provide are positively related to children’s executive functioning skills, whereas their intrusiveness and control are negatively related to children’s executive functioning skills (see Koşkulu-Sancar et al., 2023, for review). Importantly, executive functioning skills are malleable; they improve when family economic circumstances improve, consistent with neurobiological evidence from animal models (Hackman et al., 2015; McEwen & Morrison, 2014).

A large body of research has examined the effects of various kinds of training on executive functioning skills (e.g., curricular/educational approaches, activities targeting particular executive functioning skills, multilingual exposure in the first years of life, computer games, physical activities; see Clements & Sarama, 2019; Diamond & Ling, 2016; and National Academies, 2017, for review). These efforts show mixed results and many questions remain about the kinds and intensity of training that are required to yield positive results, and particularly what determines generalizability and durability of training effects that are found. Diamond & Ling (2016) review existing evidence and conclude that many kinds of training enhance the trained skill in the same and similar contexts, but that generalization of trained executive functioning skills is narrow. That is, training does not extend beyond contexts that are highly similar to those used in training. Moreover, positive effects of training fade over time as is true for other cognitive skills (Diamond & Ling, 2016). There is also evidence that interventions may be more effective for children with low executive functioning skills, including children growing up in poverty and those diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (e.g., Diamond & Ling, 2016; Klingberg et al., 2005; Tominey & McClelland, 2011).

As mentioned above, preschool children’s executive functioning skills relate to their academic achievement, including later literacy (e.g., Bierman et al., 2008) and math skills (e.g., Clark et al., 2010). The relation of early executive function to mathematics is stronger than its relation to literacy, perhaps because of greater executive functioning demands of early mathematics (e.g., Blair et al., 2011; Fuhs et al., 2015; McClelland et al., 2014; Monette et al., 2011; see Clements et al., 2016, for review). Of course, correlational evidence leaves the directionality of the executive function–academic achievement relation ambiguous, and experimental evidence is needed to determine the causal direction of these relations (e.g., Van der Ven et al., 2012; see Clements et al., 2016, for review). One study

used this approach to examine the effects of different preschool curricula on children’s kindergarten executive functioning skills. Findings of this randomized experiment showed that children who received the Building Blocks math curriculum in preschool had stronger executive functioning skills in kindergarten compared with both children in the Building Blocks plus Scaffolding Executive Functioning condition and the Business-as-Usual condition (Clements et al., 2020). These findings suggest that curricula that engage children in mathematical thinking have spillover effects that are beneficial to executive function, and in fact work better than a curriculum that focuses on both mathematics and executive functioning skills.

There is also some evidence that early education programs that directly support children’s executive functioning skills are beneficial. For example, Montessori and Tools of the Mind curricula, where teachers are trained to exercise children’s executive functioning skills, improve these skills more effectively than did curricula in control classrooms (Diamond et al., 2019; Lillard & Else-Quest, 2006).

Relatedly, research is needed to develop curricula and pedagogical approaches that support the learning of preschool children who display a wide range of executive functioning skills. This is particularly important as executive functioning skills develop rapidly during this period. Moreover, these settings often include children of different ages, further contributing to the variability in the executive functioning skills of children in the same classroom.

Language Learning

Young children are prodigious language learners from birth; this is true across cultural contexts (see Chapter 7 for a detailed discussion of multilingual learning). Of course, language learning depends on having access to language experiences, which vary both quantitatively and qualitatively within and across cultural contexts. A key takeaway from research on language learning is that it is resilient: across cultural contexts, children have capacity to learn their native language and multiple other languages (National Academies, 2017).

Language learning begins during the first year of life. An important early aspect of language learning is a perceptual narrowing of phonemic discrimination, which is characterized by an increase in native phoneme perception and a decrease in nonnative phoneme perception in the second half of the first year of life, as a result of language experience (Kuhl et al., 1992, 2006; Werker & Tees, 1984). Moreover, this narrowing is associated with more advanced language development at later ages during the preschool period, providing evidence that it is an important step in the commitment of the brain to a child’s native period, and may represent a sensitive or critical period in language development (Kuhl et al., 2005).

As noted, the rate at which young children learn language is related to the quantity and quality of their language experiences. For example, preschool children who hear more words and a more diverse set of words show higher levels of vocabulary knowledge (e.g., Huttenlocher et al., 1991). Similarly, Huttenlocher et al. (2002) found that when teachers used more complex sentences in school (defined as sentences including more than one clause), children had better comprehension of complex sentences at the end of the school year, after controlling for the overall quality of the classroom environment and children’s comprehension of complex sentences at the beginning of the year.

Other studies have focused on qualitative aspects of children’s language interactions, including parents’ responsiveness to children’s vocalization, turn taking, and question asking, and how these interactions relate to language learning. Findings show that parents’ responsiveness to children’s early vocalizations (at 9 and 13 months of age) predicts children’s vocabulary growth over and above their earlier milestones (Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2001). Parents’ responsiveness is hypothesized to increase young children’s pragmatic understanding that language is a tool for sharing intentions, which propels their language learning (Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2014).

Sociopragmatic approaches to language development emphasize the role of both members of the parent–child dyad and their joint attention in language interactions and in children’s language learning (e.g., Bruner, 1983; Nelson, 2007; Tomasello, 2003). Research within this framework has examined how turn taking between an adult and child influences the child’s language development. As shown in a meta-analysis, turn taking and adult word counts predict children’s language proficiency independently (Wang et al., 2020). In addition, turn taking is related not only to the language skills of 4- to 6-year-olds, but also to neural activation in the left inferior frontal gyrus (Broca’s area), which is implicated in language processes (Romeo et al., 2018). Taken together, these findings support the role of language interaction and active child involvement in the growth of language skills.

Tomasello (2020) theorizes that understanding a communicative partner as an intentional agent with whom one can share attention and collaborate is fundamental to symbolic communication and hence to the acquisition of language, which requires that the child understand that words are used to communicate with others intentionally. The importance of understanding and relating to others for language acquisition is supported by the difficulty that some children with autism spectrum disorder have with language learning (Hobson, 1993; Tomasello, 2000).

Relatedly, asking children open-ended questions supports their language development as well as their autobiographical memory skills; this is the case in the context of both play and book reading (Boland et al., 2003; Fivush et al., 2006; Rowe et al., 2016). Open-ended questions actively

engage children in conversations, with positive effects on their language development and on their learning more generally. Further, open-ended questions provide adults with a window into children’s language skills and thinking, which can guide the scaffolding of language development.

Research on shared book reading provides additional evidence supporting the importance of children’s taking an active role in language learning. Dialogic reading, characterized by questions and prompts that evoke participation by children, has been shown to benefit children’s language skills, including their vocabulary and narrative skills, both immediately after interventions and after delays. Positive effects of interventions involving dialogic reading have been found in studies involving parent–child dyads as well as those involving early childhood educators and their students (Beals et al., 1994; Whitehurst et al., 1988; Zevenbergen et al., 2003). These beneficial effects have been found for both native English speakers and children who are English language learners (Brannon & Dauksas, 2014). There is also evidence that this approach benefits the language development of preschool children with language learning disabilities (Crain-Thoreson & Dale, 1999; Dale et al., 1996). Moreover, even though shared book reading represents a relatively small percentage (9%) of young children’s overall language input, evidence shows that it supports the language development of children between 1 and 2.5 years of age, after controlling for the language children hear in non–book reading contexts (Demir-Lira et al., 2019). This may be the case because books contain more diverse vocabulary and more complex syntactical structures than language shared outside of the book reading context (Demir-Lira et al., 2019; Montag et al., 2015).

Another aspect of shared book reading that is important in supporting children’s identity development and sense of belongingness is seeing themselves depicted in the books (discussed in more detail in Chapter 4). However, racially minoritized (Adukia et al., 2021) and female characters are underrepresented in children’s books (Casey et al., 2021). These findings are important, as depictions in books provide children with cues as to what is possible for them, and the underrepresentation of certain groups serves to limit possibilities for children in those groups.

Cultural context is another important dimension of language learning. Although children in all cultures hear both child- and adult-directed speech (also referred to as overheard speech), the relative amounts of these kinds of input vary markedly across cultural contexts. On average, for example, 65% of the language heard by young North American children aged 3–20 months is child directed (range 17–100%), with this percentage increasing with increasing maternal education (Bergelson et al., 2019). Moreover, research found no significant change in the amount of child-directed speech over this age range, but a decrease in adult-directed speech. In contrast, children in certain cultural contexts (e.g., Mayan cultures in Mexico) hear much less

child-directed speech than do children in the United States. A longitudinal study compared the amount of child- and adult-directed speech heard by Yucatec Mayan children growing up in rural villages in southern Mexico and urban American children during the second and third years of life. At 13 months of age, only 21% of utterances heard by the Mayan children were child-directed, compared with 69% for 14-month U.S. children. By 35 months of age, however, 60% of the speech heard by the Mayan children was child directed, compared with 62% for the U.S. children at 30 months (Shneidman & Goldin-Meadow, 2012). This convergence in the amount of child-directed speech by 3 years of age may reflect that by this time, adults in both cultures consider children to be conversational partners.

Despite these differences in exposure to child-directed speech in different cultural contexts, there is evidence that children who hear less child-directed speech achieve language milestones, including first words and first word combinations, at the same age as U.S. children who hear more child-directed speech, supporting the resilience of language development (Casillas et al., 2020). This may be the case because children hearing low amounts of child-directed speech increase their attention to adult-directed speech, or because child-directed speech occurs in routine contexts with repetition—in other words, in bursts—which makes it more interpretable by young children. Hypotheses for how children in environments with little child-directed speech achieve language milestones at about the same ages as children who hear large amounts of child-directed speech include its burstiness and children’s increased attentiveness to others-directed speech (Casillas et al., 2020; Schwab & Lew-Williams, 2016).

Although early language milestones are resilient, and children in diverse cultural contexts become fluent speakers of the language(s) to which they are exposed, there is also evidence that child-directed speech is more closely related to vocabulary size than is overheard speech in and across disparate cultural contexts. This is likely the case because child-directed speech focuses on aspects of the world to which children are attending, and that they therefore are more likely to understand (Shneidman et al., 2013). Nonetheless, and importantly, it is possible that learning language in contexts in which overheard speech predominates may build important strengths in deploying attentional capacities (e.g., Casillas et al., 2020).

Math Learning

Building on core knowledge about number and space, children’s mathematical thinking and skills grow rapidly during the preschool years. Moreover, children’s mathematical knowledge at kindergarten entry is related to long-term learning trajectories in mathematics, as well as academic achievement more broadly (Claessens et al., 2009; Duncan et al., 2007;

Watts et al., 2014, 2018). These relations hold after controlling for other likely predictors of mathematics achievement, including socioeconomic status, which underscores the importance of gaining greater understanding of young children’s math learning and how to support it.

Broadly, early math skills include numerical skills, spatial skills, understanding of patterns, and understanding of data and measurement (NRC, 2009). Within the numerical domain, children typically learn the count list and how to use it to enumerate the number of objects in a set. Notably, during the preschool years, children gain an understanding of key counting principles, including (1) the one-one principle (each item should be tagged by a count word once and only once), (2) the stable-order principle (count words must be ordered in the same sequence each time a count is carried out, (3) the cardinal principle (the number word used to tag the last item is the summary symbol for the set size, (4) the abstraction principle (any set can be counted), and (5) the order-irrelevance principle (the items in a set can be tagged in any order; Gelman & Galistel, 1978). They also gain the ability to order sets, to compare the magnitude of sets, to compose and decompose sets, and to carry out simple calculations (e.g., Clements & Sarama, 2014; Feigenson et al., 2004; Fuson, 1988; Le Corre & Carey, 2007; Litkowski et al., 2020; Sarama & Clements, 2009; Wynn, 1992).

Although the attainment of early math skills is often viewed as synonymous with learning numerical skills and perhaps the names of shapes, these important aspects of mathematics do not represent the entirety of children’s foundational math concepts. Notably, early math skills include two core areas: numerical thinking, which includes understanding whole numbers, operations, and relations; and geometry, spatial thinking, and measurement. Additionally, young children learn to notice relations and patterns, to reason about these relations, and to communicate their mathematical ideas (see NRC, 2009, for review). During the preschool years, for example, children gain foundational spatial skills, including the ability to categorize shapes based on their defining features; to compose and decompose shapes; to mentally manipulate shapes; and to represent relations among environmental entities, as well as the self and environmental entities (e.g., Casasola et al., 2020; Fisher et al., 2013; Hawes et al., 2015; Levine et al., 1999; Newcombe & Huttenlocher, 2003; Pruden et al., 2011). Moreover, children’s numerical and spatial skills are highly related, and some researchers argue that mathematics is inherently spatial (e.g., Clements & Sarama, 2011; Dehaene, 1997; Verdine et al., 2017). Teaching young children spatial skills—either mental transformation skills or visuospatial working memory skills—also leads to improvements in performance on numerical tasks (Cheng & Mix, 2014; Mix et al., 2021).

Mathematical activities, both formal and informal, and “math talk” (talk about number and spatial relations) in the early home environment

vary widely and are related to children’s mathematical knowledge at preschool entry and beyond (Baroody & Ginsburg, 1990; Blevins-Knabe & Musan-Miller, 1996; Casey et al., 2018; Gunderson & Levine, 2011; LeFevre et al., 2009; Levine et al., 2010; Pruden et al., 2011; Ramani et al., 2015; Susperreguy & Davis-Kean, 2016). Opportunities to learn mathematics in early education settings also vary widely and are correlated to both math learning over the preschool year and achievement in mathematics through at least eighth grade (e.g., Claessens & Engel, 2013; Claessens et al., 2009; Duncan et al., 2007; Klibanoff et al., 2006).

Beyond studies reporting correlations between math learning opportunities and outcomes, several experimental studies have found that math learning opportunities are causally related to preschool children’s early mathematics skills (e.g., Gibson et al., 2020; Ramani & Siegler, 2008; Siegler & Ramani, 2008). Consistent with these findings, preschool math interventions have been found to lead to gains in mathematics over the school year and to higher math skills as late as fifth grade (e.g., Raudenbush et al., 2020; Watts et al., 2018). Thus, children’s math learning opportunities play an important role in their early mathematical development.

Qualitative aspects of the math learning opportunities young children experience are also related to their math learning. For example, Gunderson & Levine (2011) found that parents’ number talk, when focused on actions such as counting or labeling visible sets, predicted children’s understanding of cardinal numbers; but number talk referring to more abstract sets or concepts (e.g., being 3 years old) did not. Additionally, in a parent-delivered number book intervention study, books focused on small set sizes (1–3) resulted in gains in cardinal number understanding for children who understood the meanings of only the first two number words, whereas number books focused on larger set sizes (4–6) did not (Gibson et al., 2020). This finding is consistent with research showing the power of scaffolding in the child’s zone of proximal development (Vygotsky & Cole, 1978). In an experimental study, Mix et al. (2012) found that children’s understanding of the cardinal meanings of number words was enhanced when children were provided with the cardinal label of a set and the set was then counted, but not when the set was just labeled or just counted.

Another study found that when parents used a number word accompanied by a number gesture during naturalistic interactions with 14- to 58-month-old children, the children were more likely to respond with a number word, and with the correct number word, than when parents said a number word without an accompanying number gesture (Oswald et al., 2023). Further, parents’ talk about more advanced math concepts for preschoolers attending Head Start—including the cardinal value of numbers, the ordinal relations of numbers, and arithmetic—predicted children’s understanding of these more advanced concepts better than did simpler math

talk consisting of counting and number identification. In addition, as for language development, actively engaging children in mathematical thinking through prompting and question asking has been found to be an effective way to support children’s math learning (Eason et al., 2021). These studies suggest that beyond the quantity of math learning experiences, quality also matters.

Given the heterogeneity of young children’s mathematical knowledge, connected to variations in their opportunities to learn math concepts and skills in the early home environment, teachers face an instructional challenge in supporting children’s math development in early education settings. Formative assessments can help teachers provide instruction that is tuned to children’s skill levels. To assess whether such assessment would result in positive learning results, Raudenbush et al. (2020) randomly assigned 49 classrooms serving children mainly from low-income backgrounds to a treatment or a business-as-usual control group. Teachers in the treatment classrooms implemented an assessment–instruction system, consisting of three cycles of formative assessments linked to instructional strategies. The researchers found positive effects of the intervention on children’s foundational numerical skills, as well as their verbal comprehension skills. These findings are consistent with the positive effects found for the Building Blocks system, which encourages formative assessment, on mathematics outcomes, as well as on language and literacy (Clements & Sarama, 2008; Sarama & Clements, 2003; Sarama et al., 2012). They also mirror findings with elementary school children showing positive effects of this kind of approach (Connor et al., 2018; Hassrick et al., 2017). Taken together, these findings suggest that young children’s math learning benefits when input is tuned to their knowledge levels, and that such a focus on math learning does not take away from but benefits their learning of language and literacy skills.

The above findings from naturalistic observations and experimental studies in laboratory, home, and school environments provide important information on effective ways to support children’s number knowledge. However, this research has focused mainly on middle-income families from Western cultures and countries and needs to be extended to more diverse samples. Emerging evidence, mainly from studies of older students, indicates that math learning is strengthened with a culturally responsive, strengths-based approach. Such an approach attends to the meaningfulness of math learning activities, which increases interest in learning mathematics. This is the case both in classrooms and in engaging families in their children’s math learning (e.g., Civil et al., 2008; Hunter et al., 2022). More research is needed to examine culturally responsive, strengths-based math instruction with young children, although existing evidence indicates that this instructional approach is likely to be beneficial.

Science and Engineering Learning

Related to the way they strive to understand their world, infants and young children are frequently characterized as “little scientists” who form intuitive theories about how physical and social aspects of their world operate. Supporting this view, by preschool age children can make inferences and predictions and carry out explorations that allow them to infer causal structures (Gopnik & Wellman, 2012; Kuhn, 2012; Lapidow & Walker, 2020; Shtulman & Walker, 2020; Sobel & Legare, 2014). They do this by exploring the world independently (Cook et al., 2011; Lapidow & Walker, 2020), by asking discriminating questions (Chouinard et al., 2007; Ruggeri et al., 2019), and by observing others (Mills, 2013; see Shtulman & Walker, 2020, for a comprehensive review). Beyond this behavioral evidence that children’s acquisition of knowledge resembles that of scientists (Carey, 2013; Gopnik, 2012), computational models and Bayesian inferencing have provided evidence that young children’s theory building and change are based on their prior understandings and the statistics of the new evidence they gather, much like the activities involved in scientific theory building (Gopnik, 2012; Gopnik & Tenenenbaum, 2007; Griffiths et al., 2011; Xu, 2019).