Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Wildland Fires: Toward Improved Monitoring, Modeling, and Management: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: Future Management to Support Net-Zero Targets

Future Management to Support Net-Zero Targets

The third and final day of the workshop focused on accounting for wildfire emissions as part of country-level greenhouse gas (GHG) inventories and the range of mitigation options to reduce future wildfire emissions and increase resilience of ecosystems to climate change impacts.

ACCOUNTING FOR WILDFIRE EMISSIONS IN NATIONAL REPORTING AND NET-ZERO TARGETS

Werner Kurz, Natural Resources Canada, motivated the discussion toward achieving net-zero targets by noting that to limit warming to 1.5°C, net-zero anthropogenic (human-driven) emissions must be reached by 2050, and emissions must be net negative during the second half of the century. Achieving net-negative emissions means that anthropogenic carbon removals would be greater than anthropogenic emissions, and there is an expectation that the land sector—particularly forests and wood product carbon storage—will contribute to these removals; however, these forests are at risk from climate change impacts, including from fires.

In the first session, speakers introduced the impacts of wildfire emissions on national GHG reporting and the implications for net-zero targets through three country-specific case studies. Speakers described the magnitude of GHG emissions from wildfires in Canada, the United States, and Australia and the ways these emissions are accounted for and reported.

National Emissions and Reporting

Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)—198 countries—self-report their national GHG emissions; these reports can then be used to evaluate whether countries are meeting their emission reduction targets. However, national accounting of net GHG emissions only includes direct anthropogenic emissions and removals, Kurz explained. Under the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reporting guidelines, countries can separate emissions from forests into “managed” or “unmanaged” categories.1 In Canada—the focus of Kurz’s remarks—there are 226 million hectares of forest for which emissions and removals have been reported annually since 1990, but approximately 121 million hectares of unmanaged forest where only land

___________________

1 The IPCC defines managed land as “land where human interventions and practices have been applied to perform production, ecological or social functions” (IPCC, 2006). IPCC guidance provides latitude for governments to refine the definition of managed land to meet their national circumstances (Ogle et al., 2018).

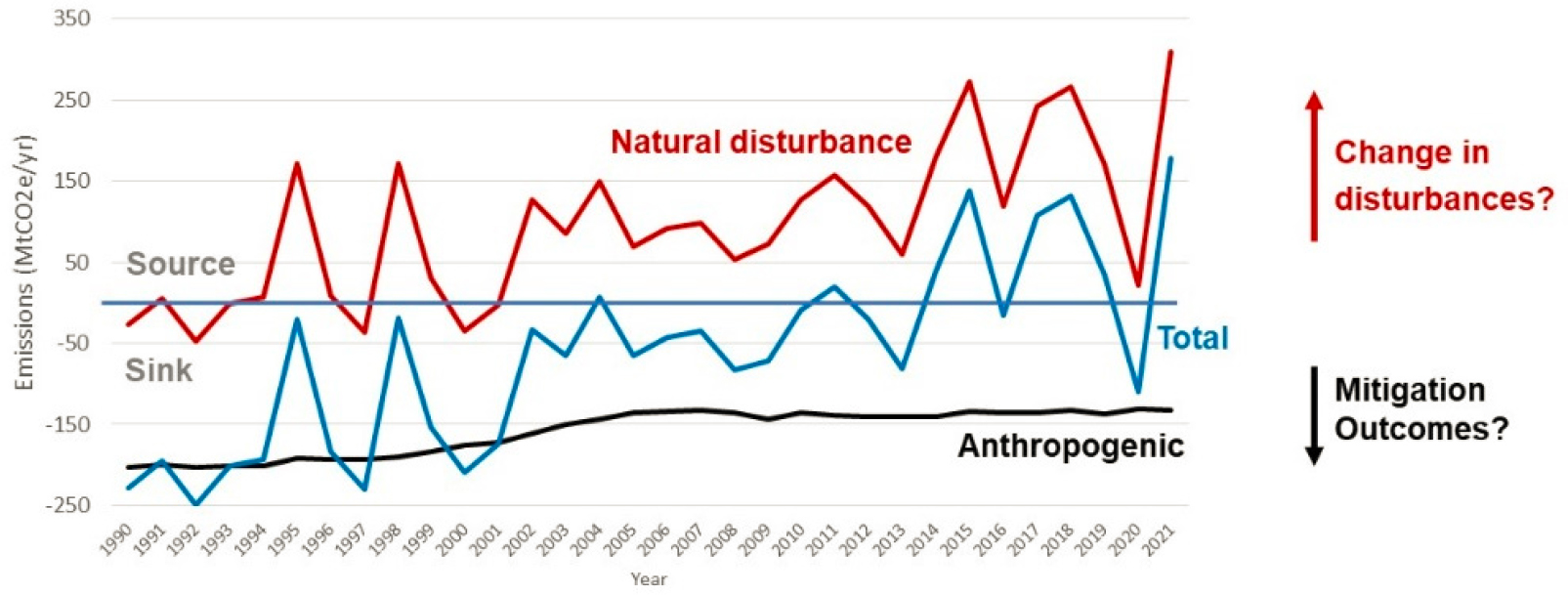

use changes are monitored and reported. In Canada, there is large interannual variability in emissions from managed forests driven by area burned, and there has been an increase in GHG emissions from managed forests such that they have transitioned from a carbon sink to a source over the past two decades (Figure 16).

The interannual variability in Canada is driven by natural processes (“disturbances”)—which are being influenced by climate change—while anthropogenic emissions from direct human influences have steadily increased over time. The question from an emissions and management perspective is whether mitigation can bend the anthropogenic emissions curve or if changes in natural processes due to climate change will overwhelm any mitigation actions (Figure 16). Prior to 2023, 2021 had been the worst fire season in Canada since 1990 with direct fire emissions of 290 million tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e). In 2023, as of the time of the workshop in mid-September, the fire emissions were roughly three times larger than emissions in 2021, and emissions from managed forests alone were 1.4 times the GHG emissions from all other sectors in Canada combined.

The recent fires in Canada demonstrate the differences between mitigation actions, which affect a small proportion of the forest in some years, and impacts from climate change, which affect all forests every year. Kurz explained that analyses of the last 20 years have shown that disturbance impacts consistently exceed mitigation benefits by one to two orders of magnitude or more. In addition to the direct emissions from fires, the decay of fire-killed trees also contributes to indirect GHG emissions in the years after fires.

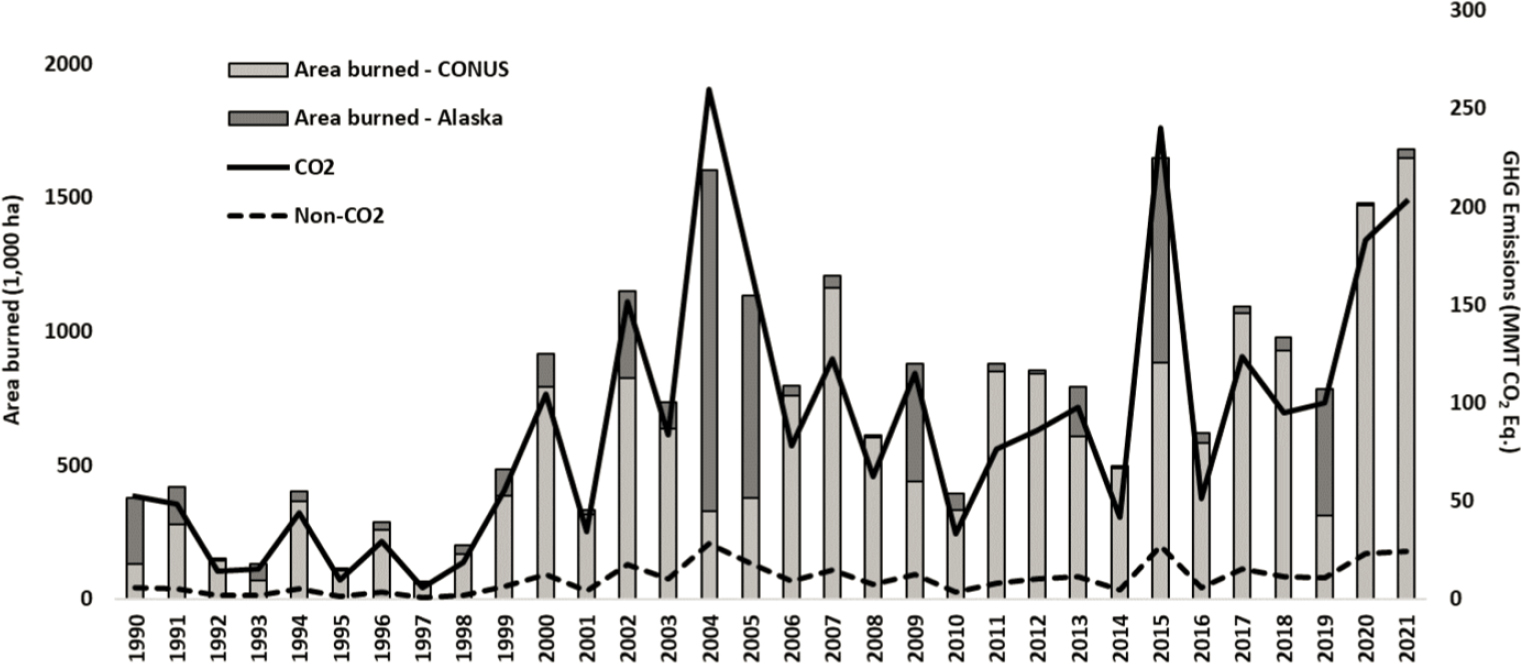

Grant Domke, U.S. Forest Service, focused on U.S. wildfire emissions from the land sector from 1990 to 2021. In the United States, the land sector2 is a sink of carbon and offsets the equivalent of approximately 13 percent of economy-wide emissions. The strength of this carbon sink, primarily from the forest land sector, has declined in recent years in part due to the frequency and magnitude of wildfire emissions (EPA, 2023). In addition to emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) wildfires are the largest source of nitrous oxide (N2O) and second-largest source of methane in the land sector (EPA, 2023).

For the purposes of reporting GHG emissions to the UNFCCC, of the land base in the United States, about 95 percent is considered managed—essentially the entire contiguous United States (CONUS) and most of Hawai`i, with forests representing one-third of the managed land; all of the unmanaged land is in Alaska (Ogle et al., 2018). Like Canada, the United States only reports emissions associated with managed lands, though they do compile (but do not report) emissions and removals for the unmanaged lands in Alaska. U.S. wildfire emissions are compiled using the Wildland Fire Emissions Inventory System, which uses burned area from the Monitoring Trend and Burn Severity records, observations from the MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) satellite, and an inter-agency dataset together with other modules to estimate combustion and emissions per fire. Figure 17 shows annual emissions and area burned from 1990 to 2021 in which there is large interannual variability, like for Canada, including the contribution of fires on managed land in CONUS versus Alaska. Domke also highlighted that quantifying prescribed fire on managed lands in the United States remains a large uncertainty, and noted that better integrating and harmonizing different emission estimates would be important, particularly as prescribed fire is considered as a management tool.

David Bowman, University of Tasmania, discussed carbon accounting in Australia where there have also been massive emissions from fires recently; in particular, the 2019–2020 fires were estimated to be 1.6 times Australia’s national anthropogenic emissions for 2019 (Crippa et al., 2020). However, these large wildfire emissions were not captured as part of Australia’s national “net” emissions. Australia reports their emissions following the UNFCCC guidelines for the land use, land use change, and forestry (LULUCF) sectors in which GHG emission calculations vary by vegetation type and whether the land is managed or unmanaged. For example, deserts are considered in the guidelines to be unproductive, so even though they do burn in Australia, those emissions are not counted.

National GHG inventories are designed to reflect human-induced emissions. A number of assumptions are built into the UNFCCC guidelines: fire disturbances are assumed to have a transient effect on GHG emissions; carbon stocks are assumed to rapidly recover and return to pre-fire levels; fires on managed land are assumed to be patchier, less severe, and different from unmanaged wildfires; and historically and geographically, anomalous wildfires in forests have been excluded from national anthropogenic emissions estimates because they are assumed to be beyond human control (Bowman et al., 2023). Major unmanaged landscape fires are disaggregated from Australia’s national total emissions and reported separately under the “national disturbance provision.”

___________________

2 The land sector includes emissions and sinks related to land use, land use change, and forestry.

Opportunities to Improve Emissions Accounting Moving Forward

Speakers explained that moving forward, it would be important to quantify emissions from natural processes that are not currently a part of national GHG inventory reporting. Domke echoed the importance of accounting for emissions and removals on both managed and unmanaged lands. Kurz explained that in Canada, the largest limiting factor for including unmanaged land in emission inventories is the limited forest inventory data, though Canadian scientists are making advances using remotely sensed data. The United States does estimate unmanaged land in Alaska, and Domke explained that they are using data on managed land to inventory unmanaged land in the interior of Alaska. Bowman added that GHG emissions accounting can be used to incentivize forest management, as has been done in tropical savannas in Australia. However, not accounting for major unmanaged fires as part of national reporting disincentivizes management efforts to avoid these types of fires.

The quantification and reporting of these emissions raise the question: who is responsible for the direct and indirect GHG emissions from wildfires driven by climate change? Kurz explained that because nonanthropogenic emissions from fires are not reported and accounted for in national net-zero emission targets, global emissions would have to be further reduced in other sectors to truly achieve net-zero GHG emissions. For global forests to contribute to net-zero targets, Kurz argued for shifting the focus from timber management to carbon management with the goal of increasing carbon sinks and forest resilience to future climate change impacts. Domke called for holistically considering all lands and communities when moving toward the idea of carbon stewardship on the landscape.

Kurz noted that there is an expectation based as part of many countries’ nationally determined contributions that the forest sector will contribute toward national net-zero targets. However, the effects from climate change on forests in many countries are such that emissions are overwhelming the ability to manage and maintain forests to enhance carbon sinks. Domke reiterated that in both the United States and Canada, forests have historically been a strong carbon sink; however, rather than assuming that forests will maximize their capacity as a carbon sink in the future, a more realistic goal may be to maintain current forest sink capacity in some areas. Kurz suggested changing the mental model of forests as a mechanism to store carbon in the landscape—because of the potential release from wildfires—to a focus on forests as a mechanism to remove CO2 from the atmosphere.

Regarding management options for forests in Canada in the context of intensifying fire regimes, Kurz highlighted that there is no single silver bullet and emphasized the challenges of scale and large differences in forests across Canada with diverse histories of fire and fuel management. Kurz offered three main management strategies that could make a difference: reducing fuel loads, reducing flammability (i.e., switching from coniferous species of higher timber value to broadleaf species of lower timber value and reduced flammability), and changing the horizontal structure of the landscape (i.e., creating more open spaces with less risk for continuous crown fire). Kurz also recognized the important role of increasing prescribed and cultural burning.

OPPORTUNITIES TO REDUCE FUTURE WILDFIRE EMISSIONS IN DIFFERENT BIOMES

The remainder of the workshop was centered around the solution space for reducing GHG emissions from wildland fires. Speakers in the next session focused on different biomes to provide specific examples of management opportunities: western United States temperate forest, North American boreal forests, tropical peatlands, tropical forests, and the range of ecosystems across Australia. Breakout discussions likewise considered climate-effective, socially inclusive, and ecologically appropriate mitigation efforts to reduce future wildfire emissions in Arctic/boreal, temperate, and tropical biomes. A clear theme throughout the session was the importance of balancing the desire to reduce emissions with cultural practices and norms and the importance of any mitigation effort to include co-planning and co-management with local Indigenous communities (Box 6).

Western U.S. Forests

Paul Hessburg, U.S. Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, focused on solutions in the western U.S. interior forest landscapes that were historically and continue to be sculpted by fire. Echoing context outlined by previous speakers, Hessburg highlighted the tens of millennia history of lightning and Indigenous ignitions in the region that created large areas of open forest, wet and dry meadows, and sparse woodlands and shrublands (Lake and Christianson, 2019). Indigenous burning focused on closed canopy forests to make food and resources available (Maclean et al., 2023; Roos et al., 2022; Swetnam et

al., 2016), but absent these fires, forests have grown denser, and many previously unforested areas are now forested (Hagmann et al., 2021). Indigenous and lightning fires burned in moist and cold forests and often as much as 35–50 percent of a large landscape area was burned or recovering after fires (Hessburg et al., 2016, 2019). The continental United States is now in a large fire deficit in terms of area burned compared to historical pre-industrial burning (Abatzoglou et al., 2021; Leenhouts, 1998; Parks et al., 2015).

BOX 6

Co-management of Wildfires and Emissions with Indigenous Communities

Session speakers emphasized that working with and respecting Indigenous and cultural practices of local communities is a critical part of any management strategy. Paul Hessburg pointed to the importance of co-planning and co-management with Indigenous communities to restabilize forest conditions in the western United States and noted that dialogue is critical because fire management practices often vary by tribe, band, or family group. Geoff Cary added that because of large differences in landscapes and fire regimes in Australia in some places, the long-term reintroduction of frequent cultural burning may be advantageous with respect to reducing GHG emissions (Figure B), whereas other places may need a long-term absence of fire. Because the flammability of landscapes—for example, in the Xingu Basin in the southeastern Amazon—has changed so much, Marcia Macedo pointed to the need for co-learning about how to use fire for both cultural and fire control purposes to achieve shared goals. Peter Frumhoff added that new projects aiming to co-design management strategies can serve as testbeds and models for how to co-design and co-produce knowledge for fire management.

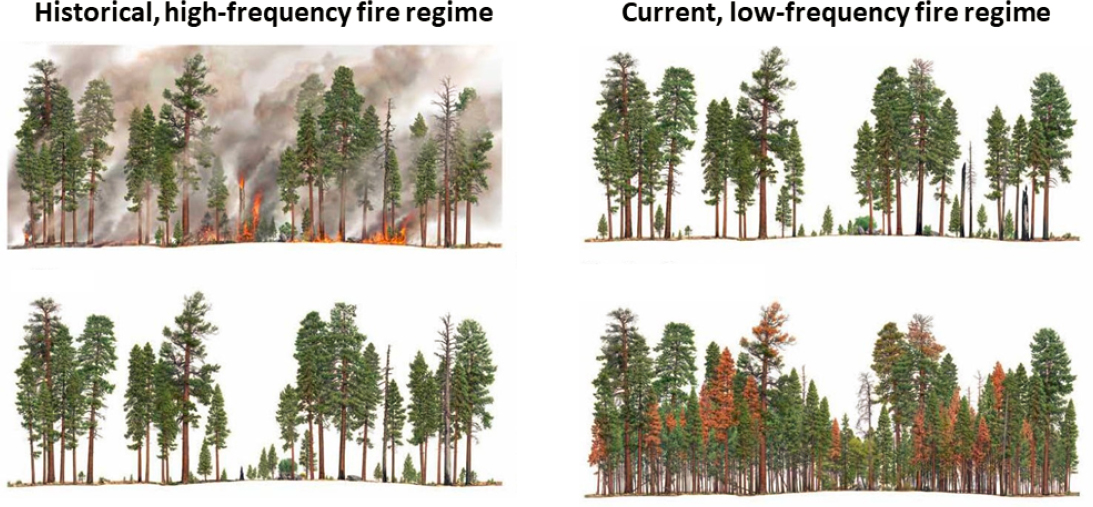

The historic regime of frequent low- or moderate-severity fire was an important stabilizing feedback that led to forest conditions that were in sync with the climate and native vegetation and improved the likelihood that the next fire would also be low to moderate severity (Figure 18). Forest reburning is an essential large landscape-stabilizing feedback (Hessburg et al., 2019; Povak et al., 2023; Prichard et al., 2017). In the historical regime, fires of varied sizes and severity—that overlapped in space and time—created shifting mosaics of forest and nonforest conditions that self-regulated by dampening fire sizes and their severity. Additionally, nonforest areas within large landscapes (25–75 percent of large landscapes as shrubland, sparse woodland, wet and dry meadows, wetlands) also limited future fire size and severity.

Without these high-frequency fires, trees quickly accumulate, allowing flames to climb the layered subcanopy, resulting in the crown fires experienced in the western United States today (Figure 18). Hessburg explained that the shifting reburn and recovery mosaic of the past is the missing ingredient today, and the current forest cover in the interior West is not sustainable for forested ecosystems. Current conditions have made the interior West more vulnerable to fire: increased canopy fuels intensify energy available for severe fires; increased connectivity of fuels creates opportunities for large and spreading fires; and changes in climate and weather increase fuel curing and area burned, meaning high burn severity conditions are readily available at regional to provincial scales.

The change agents beginning in the 1800s up to the present day included fire exclusion (e.g., reduced Indigenous burning, land development for agriculture and urban settings, fire suppression), timber harvest, climate change (e.g., increased temperatures and wind, longer fire seasons, reduced snowpack), and smoke management (e.g., regulations to reduce intentional burning). With this context, Hessburg highlighted a number of potential solutions to reduce future wildfire emissions in interior western U.S. forests:

- Increasing open-canopy forest conditions (i.e., less fuel accumulation) (Figure 18) and reestablishing burned and recovering mosaics of forest and nonforest conditions;

- Stabilizing the competing factors that grow and remove forests through management that would, for example, restore nonforests, hardwood forests, and wetlands, and open-canopy forest conditions; and

- Restoring the positive ecological role of fire by incorporating Indigenous knowledge, practice, and management leadership, using the tools of cultural and prescribed burning, forest thinning, and biomass removal that can contribute to a bioeconomy.

Breakout discussions focused on management in temperate forests broadly. One breakout echoed the importance of increasing prescribed and cultural fires and pointed to a strategy of strategically targeting ecosystems based on either the risk of carbon loss or the vulnerability of the ecosystem itself to loss from fire. Relatedly, other participants discussed the conditions that could be helpful to transition to an adaptive management fire regime, including increased public awareness and comfort with prescribed burning (and the resulting smoke) and shifting frameworks for forest management to choosing when to have fire and smoke, not whether to have it. Discussions also recognized conflicting land management priorities and noted the importance of supporting and incorporating Indigenous practices and cultural burning and potential opportunities to incentivize land managers to accomplish mitigation goals. Participants recognized the heterogeneity of temperate landscapes that involve different approaches and the importance of examining local examples of adaptations to the social and environmental conditions of a place, for example, from Indigenous communities.

North American Boreal Forests

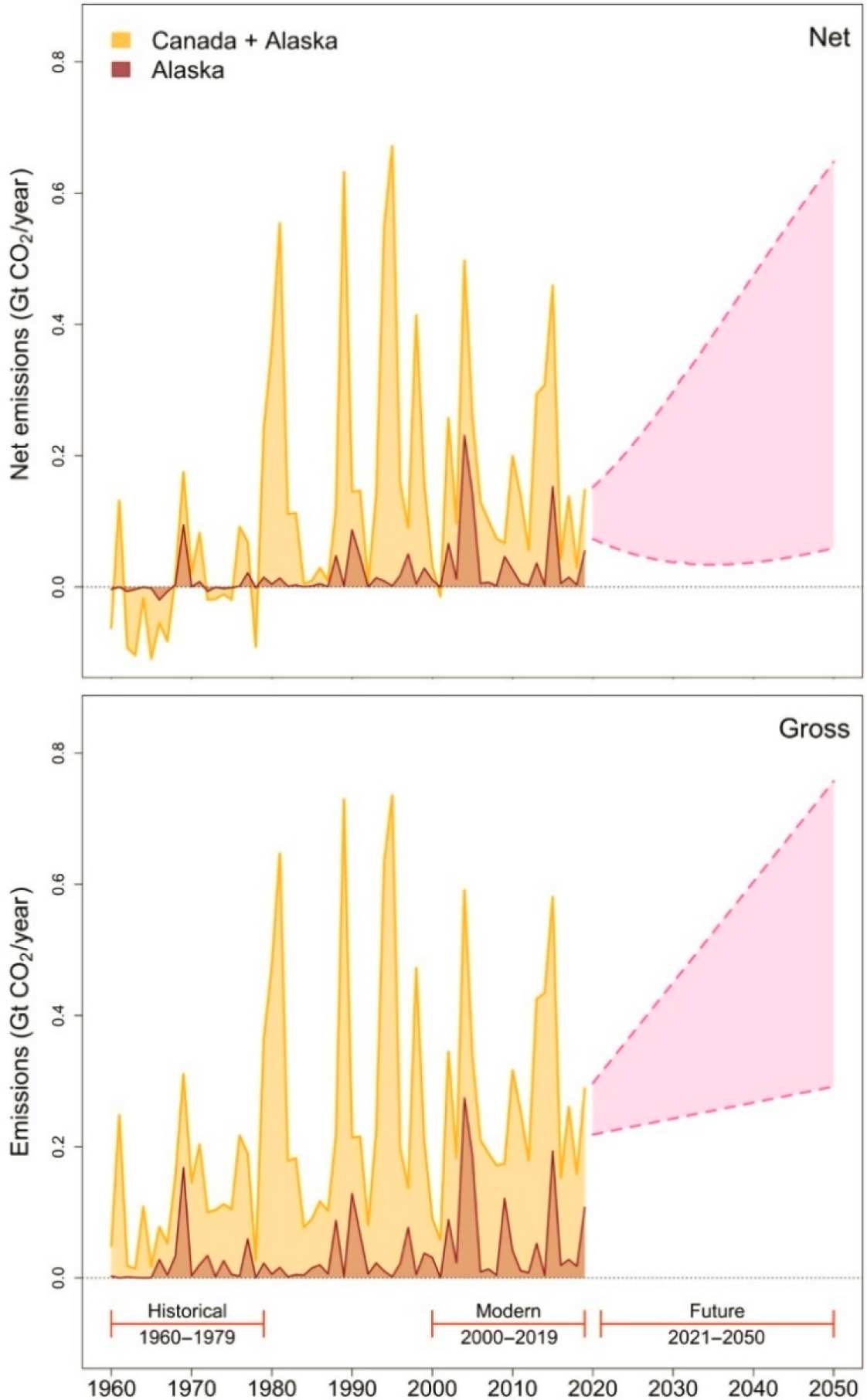

Peter Frumhoff, Harvard University and Woodwell Climate Research Center, focused on fires in the Alaskan and Canadian boreal forests. The burned area of wildfires in Alaska and Canada have roughly doubled since the 1960s (Figure 19) (Phillips et al., 2022). This increase is strongly linked to climate change, and these trends are expected to continue without effective fire management interventions at a large scale. Phillips et al. (2022) estimated that wildfires in Alaska and Canada could contribute to a cumulative net source of up to 12 gigatons of net CO2 emissions by 2050 (Figure 19), which may be a

conservative estimate in light of Canada’s 2023 fire season (on the order of 2 gigatons CO2 equivalent at the time of the workshop).

Wildfires in Alaska and other boreal forests are not currently managed with the goal of limiting carbon emissions. Current fire management practices in Alaska focus on protecting lives and property and are geographically prioritized by fire management zones in which the greatest suppression efforts go toward fires in the “critical” zone. Phillips et al. (2022) found that the fire management zone explains approximately 22 percent of the total variability in fire size in Alaska. When management data on effectiveness in reducing emissions are tied to economic data for the cost of fire suppression, fire management in Alaska appears to be a viable and cost-effective approach to keep carbon in the ground and out of the atmosphere. On the basis of this analysis, Frumhoff proposed that one approach to limiting GHG emissions in the North American boreal forests may be to target fire suppression for carbon protection early in the season before fires become large in order to support the overarching goal of maintaining wildfires at historically or ecologically sustainable, pre-climate change levels.

This management approach is being piloted in the Yukon Flats National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska by the Bureau of Land Management and the Fish and Wildlife Service in which they are designating a change in the fire management regime for 1.6 million acres across the refuge that are underlain with carbon-rich Yedoma permafrost. The goal of the project is to slow the release of GHGs to the atmosphere and reduce air pollution while maintaining wildfire habitat diversity. Frumhoff noted that this field experiment will help determine the potential for targeted suppression of boreal wildfires to limit GHG emissions.

To the question of managing boreal wildfires more broadly, Frumhoff pointed to the other impacts of wildfires (e.g., black carbon deposition on snow and ice, smoke inhalation and consequences for human health), and recognized the opportunity to consider other co-benefits—beyond reducing GHG emissions—of wildfire management that may motivate different interested and affected groups and policymakers to limit wildfires (e.g., co-benefits for aviation, tourism, infrastructure). Frumhoff also made the point that fire management in the boreal will require real investments. According to one estimate, managing Alaska wildfires to pre-climate change levels would require an average annual investment of $700 million through 2030, roughly five times the current level of annual investment in Alaska wildfire management (Phillips et al., 2022).

Frumhoff concluded by making the point that expanded wildfire management to limit GHG emissions in the boreal only makes sense in the context of broader national and international commitments to deep decarbonization. While limiting wildfire emissions and maintaining carbon in the landscape would help buy time, warming and wildfire intensity ultimately will continue to increase until global emissions reach net zero and net negative. For this reason, Frumhoff urged caution around using carbon markets as the primary source of financing for limiting boreal wildfires so as not to inadvertently undermine the importance of deep fossil fuel emission reductions. Frumhoff also underscored that any consideration of altered fire management in the boreal forests would need to fully engage and consider the perspectives and priorities of Indigenous communities who have long been

the stewards of the landscape but have too often been left out of the design of fire management plans and priorities.

Breakout discussions that focused on management in Arctic and boreal regions highlighted additional challenges and opportunities in the region. Discussions noted the unique challenges of managing fires in the Arctic/boreal region, including the large scale and remoteness, limited resources and infrastructure, large interannual variability, geopolitical challenges (i.e., Russia representing two-thirds of the Arctic/boreal zone), and the rapid pace of warming. While there are a variety of different management options—cultural burning, fuel and vegetation treatment, prescribed burning, forest regeneration, wetland protection—the challenge is understanding and agreeing on when and where to apply these strategies in consultation with communities. Other breakout discussions recognized the importance of education and outreach to the public and policymakers and pointed to the possibility for economic incentives to stop inhibiting deciduous growths. Finally, many participants noted that management solutions likely involve broader policies that both reduce global fossil fuel emissions and consider carbon and climate as part of fire management.

Tropical Peatlands

Susan Page, University of Leicester, focused on peatland fires in the tropics that are highly vulnerable and fire-prone systems today. The resilience of tropical peatland is primarily determined by hydrology where a high water table maintains moist peat and aboveground biomass such that fire is not a natural feature of these ecosystems. Prior to development in Southeast Asia and other intact tropical peatlands, there was no or low fire risk. Recently, the additions of agriculture and people—for example, people from other islands moving into Indigenous peoples’ homeland in Indonesia—have lowered the water table, exposed a large fuel base, and introduced a range of ignition sources, changing the fire regime of tropical peat systems. Additional drivers that have made peatlands more fire prone include increased drainage and incidence of drought.

Fire is used as a traditional land management tool across Indonesia, though use of fire at scale for brush clearing and plantation development has increased over the last two to three decades due to migration of people into these areas from other places. These trends have coincided with forest degradation, forest loss, and peatland drainage that together have made the landscape increasingly flammable. The government of Indonesia has implemented fire bans, controls, and regulations on peatland drainage. However, the use of fire on these flammable, remote landscapes can result in out-of-control fires that are challenging to extinguish. The smoke emissions from fires in Indonesia can impact people as far as Thailand and the Philippines, and these large fires have a large impact on the economy and people’s health in Indonesia (e.g., Koplitz et al., 2016). To manage peatland landscapes, Page offered some potential solutions:

- Reducing fire risk by focusing on the use of fire only when necessary and encouraging low or no fire land management (e.g., Fire Free Village initiatives that financially incentivize low or no fire);

- Re-wetting the landscapes (deliberate actions that aim to restore the water table of a drained peatland) while also maintaining livelihood security for communities that depend on growing dryland crops;

- Using fire danger warning systems to limit the risk of accidental ignition;

- Implementing active and ongoing fire management for landscapes where there is forest regeneration and replanting; and

- Maintaining wet peatlands by finding alternative pathways for economic sustainability that do not involve development that disrupts hydrology in peatlands.

Tropical Forests

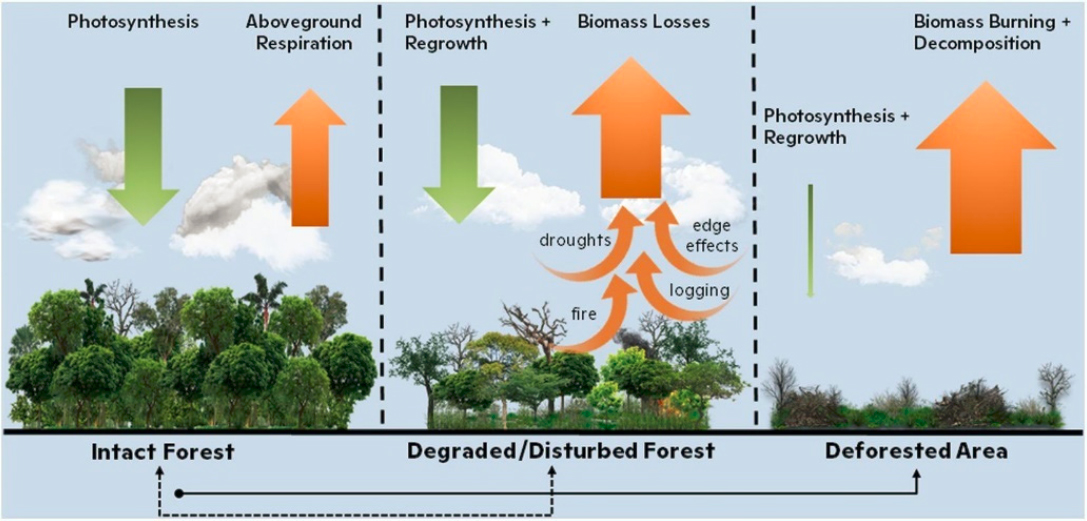

Marcia Macedo, Woodwell Climate Research Center, emphasized the importance of tropical forests as stores of aboveground biomass carbon. Recent estimates suggest that removing global forests would raise global temperatures by as much as 1°C, and the Amazon—the focus of Macedo’s work—represents about 50 percent of global forest area. The Amazon is in a state of stress; climate change and fire will be determining factors in whether tropical forests become more resilient or more degraded (Castanho et al., 2020; Trumbore et al., 2015). As in tropical peatlands, fire is not a natural part of the ecosystem in tropical forests; the main ignition sources for these fires are anthropogenic. The primary drivers of fire activity in the Amazon are fuel, ignition, and climate, and all three drivers are currently changing (Alencar et al., 2020).

The priority solution from Macedo’s perspective is stopping deforestation in the Amazon because it would address all the drivers of fire activity. Deforestation adds a new fuel source (i.e., accumulated dead biomass) to the landscape that has a high probability of ignition, emits GHGs, and changes local and regional climate. Deforested areas are roughly 5°C warmer than forested areas and recycle 30 percent less water to the atmosphere, which enhance conditions for fire. Managing forest degradation is an important strategy for reducing emissions from tropical forests (Kruid et al., 2021). The challenge is attributing the degradation to different drivers to identify intervention strategies (Figure 20). Data and modeling can also be tools for fire management in the Amazon. For example, forecasts ahead of and during active fire season can help identify locations where efforts are needed to stop fire from escaping into wildlands. Near-real-time data about fire type, for example, from the Amazon Fire Dashboard,3 can provide managers with critical information.

To emphasize the importance of wildland–agriculture interfaces, Macedo shared the example of the Xingu Basin in the southeastern Amazon where land management fires occur adjacent to large blocks of forest. Land management fires can be an ignition source, so reducing unnecessary fire use for pasture and agricultural management could help protect forested areas. Understanding the interactions between the compounding disturbances of fire and drought in this region is another challenge and piece of the solution space (e.g., Balch et al., 2015). In the Xingu Indigenous territory, every time there is a major drought, 10–15 percent of the area burns. While some burning is prescribed, roughly 15 percent of

___________________

the area is now a grass-dominated system that is fire prone and perpetuates the cycle of fire (Silvério et al., 2022).

Macedo also underscored that integrating traditional knowledge about fire use and impacts is crucial. As an example, researchers worked with communities in the Xingu reserve to study 60 useful species (e.g., used for construction or medicinal purposes, sold for reforestation) and found that about one-half of the species fruit during the late dry season when prescribed burns typically happen. Disruptions to harvesting these fruit species from prescribed burns was an unintended consequence of the management practice. This finding was shared with the fire management agency and is an example of co-developing research questions and adapting fire management strategies to benefit local communities.

Finally, Macedo highlighted additional levers that can be used to reduce fire on the landscape. First, the Amazon has large tracts of undesignated public forest that have poor governance and are prone to land speculation and fire use for deforestation, and so clarifying land tenure could reduce fire. Second, streamlining data flows and building capacity and data tools could support firefighters. Finally, supporting Indigenous land rights and leadership in the Amazon is critical, Macedo said.

Breakout discussions considered management strategies across different tropical ecosystems. Because land use change is the primary driver of fire in tropical systems, any

intervention to reduce wildfire emissions likely involves working with people and local communities. Participants discussed the goal of a participatory process with shared leadership to permit the use of fire in traditional and smallholder systems while minimizing the risk of escaped fire in humid tropical forests. Beyond community fire management, participants also discussed the inclusion of local people in academic research teams, industries, and legislative and policy discussions around fire management as well as the need for long-term investments, including for ongoing monitoring. Another unique characteristic of tropical ecosystem management is that reducing fire emissions would also mean altering human activities and thus reducing financial benefits. Consequently, many participants noted the opportunity to associate tropical forests and peatlands that should not be burned from an ecosystem health and emissions standpoint with benefits or compensation. Additional barriers to implementing management policies at scale in tropical systems include political boundaries, sovereignty, instability of governance, and corruption.

Regarding potential future research areas, participants discussed opportunities to anticipate changes in risk by tracking and forecasting seasonal and interannual changes in fire risk that reconnect tropical landscapes, permitting large, destructive fires in remote regions. Tropical ecosystems could also benefit from improved real-time monitoring of low-intensity fires, including smoldering fires in peatlands or escaped fires in tropical forests, using remote sensing tools and ground-based measurements. Several participants highlighted the opportunity to combine a series of monitoring systems that could allow for local reporting of escaped fires without risk of penalty to encourage participation and collaboration with local communities.

Australia

Geoff Cary, Australian National University, spoke about management of wildfires across the diverse landscapes of Australia. As many of the speakers discussed, wildfire management to reduce GHG emissions likely involves changing the fire regime to one that has intrinsically lower emissions; protects carbon, trees, and carbon-sequestering forests; or both. Cary shared the example of management of northern tropical savannas in Australia in which prescribed, lower-intensity burning early in the annual dry season can offset the area burned by higher-intensity, more extensive fires later in the dry season and significantly reduce non-CO2 GHG emissions (e.g., Edwards et al., 2021; Russell-Smith et al., 2013).

Management of temperate eucalyptus forests is also critical, Cary explained. For example, during the major fires of 2019–2020, approximately 18 million acres of temperate eucalyptus forests and woodlands burned in eastern Australia. Unlike in tropical savannas, prescribed burning is a more limited management solution for reducing GHG emissions (i.e., around 4 acres of prescribed burning is required to offset 1 acre of high-intensity wildfire over the next 5 years) (Bradstock et al., 2012). An alternative way to reduce wildfire extent, as suggested by Cary, is to reduce unplanned ignitions, by either preventing or rapidly suppressing ignitions when they occur, though significant advances in ignition detection and suppression technology would likely be required. Cary shared results from a

modeling study that examined the relative importance of various controls on fire in temperate or similar landscapes and found that interannual variability in weather was most important for predicting variations in area burned, followed by reducing or suppressing ignitions (reduced wildfire area in Australia model systems by >80 percent), and finally, prescribed burning (reduced wildfire extent by 25–40 percent).

Cary also considered management options to protect the carbon storage and sequestration potential of forests. For example, eucalyptus trees can store large amounts of carbon, and while most species can survive and recover from fire, some species can be killed by fires intense enough to scorch the canopy and require a fire-free period of over 10 years to regenerate (Gale and Cary, 2021). Cary discussed applying prescribed burning at the edge of these regenerating eucalyptus forests as a potential strategy for protecting carbon-sequestering eucalyptus forests.

THE SOLUTION SPACE AND EXAMPLES OF NEXT STEPS: FOREST MANAGEMENT OF TOMORROW AND LIVABLE EMISSIONS

The workshop concluded with a moderated conversation among practitioners about the solution space and examples of potential next steps for ecosystem and fire management in light of the opportunities and challenges for reducing GHG emissions identified throughout the workshop. The discussion centered around several themes that brought together threads from throughout the workshop: working with local communities; co-benefits and trade-offs between carbon, ecosystems, and livelihoods; tools for management; and the management horizon for the future.

Working with Local Communities

Jimmy Fox, U.S. Fish and Wildfire Service, manages the Yukon Flats National Wildfire Refuge in interior Alaska, which overlays the traditional homeland of the Gwich’in Athabascan people. Today, about 1,200 predominantly Indigenous people live on private lands within the boundaries of the 8.6-million-acre refuge. The Yukon Flats has 6,000 years of fire history, but the frequency of fire has increased in the past several decades, and most fires on the refuge are monitored but allowed to burn. However, these fires can threaten human health, subsistence lifestyles, natural diversity, and global climate goals. Fox elaborated on the pilot project, introduced previously by Frumhoff, in which the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Bureau of Land Management’s Alaska Fire Service have agreed to suppress wildland fires through the first half of the fire season over 1.8 million acres, roughly 20 percent of the refuge. The goals of the project are to preserve mid- to late-successional plant communities for habitat diversity, protect the estimated 1.1 Gt of carbon in Yedoma permafrost that underlies the refuge, and reduce air pollution and its impacts for the residents of the refuge.

Fox said the key to working with local communities is to show up, listen, and engage thoughtfully. Instead of a single strategy for engagement, Fox highlighted the importance of developing location- and tribal-specific approaches, which require investments of time

and resources over a sustained period of time. One lesson Fox has learned is to look for ways to engage that work for local communities rather than prioritizing his own interests as a federal land manager and to be flexible and responsive to the ways in which tribes want consultation to look.

Co-benefits and Trade-offs between Carbon, Ecosystems, and Livelihoods

Paul Hessburg, U.S. Forest Service, shared examples of co-benefits from reestablishing landscape resilience by reducing fuel loads and reintroducing the ecological role of fire in western U.S. temperate systems. Reestablishing forest resilience could stabilize CO2 uptake and storage in forests, albeit at lower levels, and protect municipal water supplies and other vital infrastructure. The wildland fuel restoration problem and the community resilience problems are quite independent and involve different mindsets and tactics (Calkin et al., 2023). Reducing wildfire vulnerability overall could improve human health (from less smoke) and protect human infrastructure. Hessburg suggested that inviting fire back into what are inherently fire ecosystems and moving beyond the fire suppression era would restore resilience to a future climate and shifting wildfire regimes.

Dan Thompson, Canadian Forest Service, provided an example of weighing the trade-offs between animals, livelihoods, and fire management strategies in Canadian boreal forests. In Canada, woodland caribou are a federally listed species at risk, and one of their primary habitats is open, old conifer forests, which are also the most flammable fuel type. Boreal forest conversion from conifers to broadleaf may be appropriate in some locations, such as near communities, but Thompson explained that there is a trade-off in habitat spaces for species at risk. Adding complexity to the management space are communities, including Indigenous communities, who run traplines for fur-bearing mammals in old conifer forests, meaning any forest conversion could also impact their livelihoods. Thompson suggested that instead of forests that are uniformly broadleaf or uniformly old conifer with fire suppression, a balanced solution may look like a mosaic of landscapes and management approaches, drawing from the traditional management model in the past Canadian boreal. A mosaic in the boreal may look different from a mosaic in temperate forests. For example, a mosaic could include pockets of old conifer forests in places that are advantageous to wildfire and away from people who would be impacted by smoke, areas broken up with lakes and islands, and the introduction of broadleaf in other areas.

Natasha Ribeiro, University of Eduardo Mondlane College of Agriculture and Forestry, spoke about the miombo woodlands in Mozambique, one of the largest dry forest ecosystems in the world. Fire has historically been part of the miombo ecosystem for more than 200,000 years. The Niassa Special Reserve, an area covering 42,000 square kilometers in northern Mozambique, has a typical fire frequency of 3–4 years; however, climate change and population growth have resulted in an annual fire frequency in some places (45 percent of the reserve), which is changing forest composition and structure. About 65,000 people live within the Niassa Special Reserve and use fire and other forest resources to maintain their livelihoods. The ecology of the miombo is determined by people, fires, vegetation, and animals, and is a challenging ecosystem to manage because of its size and

diversity of landscapes. Ribeiro called for an integrated fire management policy that would include traditional knowledge and the importance of fires in the miombo, instead of a zero-fire policy that ignores traditional knowledge and practices.

Tools for Management

Thompson said that in Canada, while there are some gaps in data, models, and observational tools needed to ideally implement and monitor solutions, they are close to having the needed tools. Even though Canada is not as densely observed as parts of Europe or the continental United States, particularly in the north, the forest is low diversity and relatively well characterized for the purposes of management. Improving prediction tools—for example, fire extent and fire growth 3–4 days into the future—are marginal improvements, and Canada is not in a place of information scarcity. Instead, Thompson explained that the real challenge for management is the extent to which climate change has disrupted the equilibrium of the boreal fire ecology. The boreal forests that are relatively old (~100-year median age) are now burning at a rate and frequency that is out of equilibrium with its natural state due to amplified warming at higher latitudes.

Thompson identified the need to provide managers with actionable information, rather than a flood of data that may not be practically useful. Thompson also noted that real-time information needs for the public may be changing. For example, many eastern Canadian community institutions (e.g., schools, daycares, outdoor sports leagues) outside of major cities do not have protocols in place to deal with severe air quality advisories as issued by the federal government, as wildfire smoke and air quality more broadly have not traditionally been an issue.

Jayaprakash Murulitharan, Cambridge University and Ministry of Environment, Malaysia, shared his perspective both as an air quality researcher and from his experience in government in Malaysia and with ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations). Murulitharan centered on the historic event in 2015 when Southeast Asia experienced severe air pollution (or haze) due to wildfires. Malaysia is affected from wildfire smoke from both the north (from agricultural burning in Thailand, Laos, and Burma) and the southwest (from peatland burning in Sumatra and Kalimantan). Over the past 7–10 years, there has been a focus on real-time and efficient data sharing between countries in Southeast Asia and efforts to establish a coordination center to ensure that fires are reported early and that weather predictions can be used to help countries prepare.

Murulitharan also noted that since 2015, there were improvements to peatland management in Indonesia, but this required a strong political commitment from the top down. Moving forward, Murulitharan said that there is a need to highlight the scale of wildfires in the region and their impact on climate to move toward wildfire mitigation and peatland management throughout the region.

However, countries in Southeast Asia have not typically made the connection between climate change and haze, Murulitharan explained. One challenge is that when fires are periodic events, there can be a focus on blaming individual countries where fires originate; a second challenge is that the focus has been on managing fires and haze in real time,

rather than translating the impact of fires on GHG emissions or the role of climate change. There is not currently harmonized data sharing between countries because each individual country has their own approach to gathering data and quantifying emissions. While there have been advances in making connections between smoke and health with the public, the translation of the impact of fires on climate change is missing.

Management Horizon into the Future

Speakers concluded the session discussing examples of goals for management and policies in the future. Hessburg explained that inviting fire back into ecosystems in the western United States would support the goal of reestablishing resilience at scale. The importance of maintenance work would remain because of the safety, human health, and economic considerations at the wildland–urban interface, in particular. In Hessburg’s view, reintroducing resilience at scale would mean reducing the need for aggressive fire suppression because fire would do some of work of ecosystem management, allowing for strategic management and suppression work around human settlements. Fox noted the importance of increasing capacity and resources for nature-based solutions for mitigation that have the co-benefits of clean air and water and protecting species at risk. Given the large U.S. National Wildlife Refuge system and amount of the nation’s carbon stocks in Alaska, Fox noted the opportunity to expand capacity to support carbon management. Murulitharan reflected on the establishment of a regional policy framework in Southeast Asia over the last 20 years to address wildfire incidence in the region. This regional, legally binding policy promotes cooperation between countries to fight and mitigate wildfires. While countries have considered or implemented laws on transboundary pollution that seek to prosecute perpetrators responsible for wildfires, Murulitharan argued for investing in a strong scientific framework to support regional cooperation and management.