Introduction

The human, environmental, and economic damages from wildland fires are a growing global challenge as wildland fires burn hotter, more frequently, and over larger areas and occur in systems where fire had not historically been part of the ecosystem. Today, climate change and certain human land management and development practices are exacerbating the conditions and locations where wildland fires develop, and the resulting intensity of those events, which can overwhelm the resources available for management (UNEP, 2022). While landscape fires are a natural part of healthy, evolving ecosystems, large, uncontrolled wildland fires can have devastating consequences on human health, communities, and biodiversity. Ecosystems store large amounts of carbon as above- and belowground biomass, and wildland fires in peatlands, tundra, forests, grasslands, and other systems can emit large amounts of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gases (GHGs) to the atmosphere.

Fires have been a natural part of the Earth system for hundreds of millions of years and have played a critical role in shaping global ecosystems (Bond et al., 2005). Climate affects fire regimes through its control on weather and interactions with vegetation productivity and structure—for example, through drought or fuel desiccation or flammability—at the global, regional, and local scales (Jia et al., 2019). Today, humans are the main source of fire ignitions globally (Bowman et al., 2017; Harris et al., 2016), and humans also influence fires by extinguishing them, reducing their spread, and managing their fuel sources, as well as broadly changing land use.

Fire transfers carbon between the land and atmosphere through emissions of GHGs, carbon monoxide (CO), particulate matter, and other gases; fire also transfers carbon between different terrestrial pools from live to dead biomass, pyrogenic carbon, and soil. After a fire burns, vegetation can recover and regrow to sequester carbon from the atmosphere as biomass over years to decades, depending on the biome type (Landry and Matthews, 2016). However, human-driven changes to climate and land use have made biomes vulnerable to changes in fire regimes and are disrupting the carbon balance of these systems.

Future changes in climate—for example, increasing temperatures, decreasing precipitation, and changing regional weather extremes—are expected to increase the risk and severity of wildfires in many global biomes (Jia et al., 2019). Continued climate-driven changes in wildland fire regimes have the potential to increase GHG emissions at a scale that could counteract global reductions in anthropogenic GHG emissions that have been made to achieve the 2°C temperature target set forth by the Paris Agreement.1 There are large uncertainties in measurements and models of GHG emissions from wildland fires

___________________

1 The Paris Agreement is an international treaty on climate change, adopted by 196 Parties at the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP21) in 2015. Its overarching goal is to hold “the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels” and pursue efforts “to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.”

today, and projections of how wildland fires and their emissions will change on decadal to century timescales. Better understanding of how the feedbacks between wildland fires, their GHG emissions, and climate change could effect global efforts to achieve net-zero GHG emissions in the coming decades would be useful. At the same time, it is important to develop and implement management strategies, including from Indigenous knowledge and practices, that could limit potential GHG emissions from wildland fires while also addressing the immediate needs of affected communities and ecosystems.

In September 2023, the Board on Atmospheric Sciences and Climate together with the Board on Agriculture and Natural Resources and the Polar Research Board of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine convened a workshop on GHG emissions from wildland fires. The workshop identified opportunities to improve measurements and model projections of GHG emissions from wildland fires, considered how changes in emissions from these fires could affect our ability to achieve “net-zero” GHG emission targets, and discussed management practices that could be incorporated in current and future action plans. See Appendix A for the statement of task to the workshop planning committee; Appendix B for biographical sketches of the planning committee members; and Appendix C for the workshop agenda. Box 1 provides key terminology used throughout the proceedings.

The structure of the proceedings largely follows the workshop agenda (see Appendix C). The 3 days of the workshop were organized around three broad themes:

- Biomes vulnerable to wildland fires and implications for GHG emissions,

- Opportunities and challenges for observing and modeling wildland fires and their GHG emissions, and

- Future management to support net-zero targets.

This proceedings summarizes workshop presentations and discussions in the plenary and breakout sessions. This proceedings has been prepared by the workshop rapporteur as a factual summary of what occurred at the workshop. The views contained in the proceedings are those of individual workshop participants and do not necessarily represent the views of all workshop participants, the planning committee, or the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Funding for this workshop was provided by SATManagement, a wholly owned subsidiary of the Environmental Defense Fund, and the National Academy of Sciences Arthur L. Day Fund.

FRAMING THE WORKSHOP

To begin the workshop, Scott Stephens, University of California, Berkeley, centered the relationship between Indigenous peoples and fire. Stephens shared a perspective on fire from Val Lopez, chairman of the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band: “Fire is a gift from creator for the stewardship of the land.” Stephens challenged the perception of fire as something only to fear as a destructive force and suggested that viewing fire as a gift is fundamental to any forward progress.

BOX 1

Key Concepts and Terminology

Environmental stewardship: The responsible use and protection of the natural environment through conservation and sustainable practices to enhance ecosystem resilience and human well-being (Chapin et al., 2010).

Fuel: Live and dead vegetation biomass that burns, including aboveground live, dead surface material, and ground-layer organic matter.

Fuels or fire management: Practices and strategies, including land management fires and cultural burning used as a tool for achieving resilient ecosystems.

Greenhouse gases (GHGs): Gases that trap heat in the atmosphere. Water vapor, carbon dioxide (CO2), methane, nitrous oxide, and ozone are the primary GHGs in Earth’s atmosphere (IPCC, 2021). Carbon-containing GHGs primarily responsible for warming (e.g., CO2) were the focus of this workshop.

Indigenous (fire) stewardship: Indigenous fire stewardship is the concept used by various Indigenous, Aboriginal, and tribal peoples to explain the intergenerational teachings of fire-related knowledge, beliefs, and practices among fire-dependent cultures regarding fire regimes, fire effects, and the role of cultural burning in fire-prone ecosystems and habitats (Maclean et al., 2023).

Land use legacy: Land condition is a result of past land use and driven by both natural state factors and human land stewardship practices.

Net zero: Requires cutting GHG emissions to as close to zero as possible, with any remaining emissions re-absorbed from the atmosphere.a

Wildland: Area in which contemporary human development is essentially nonexistent except for roads, railroads, power lines, and similar transportation or utility structures.b

Wildland fires: Fires that originate in the “wildlands,” as opposed to structure fires and fires occurring in built environments. Includes planned and unplanned burns, cultural burning, management fire, wildfire, rangeland burning, as well as escaped agricultural and other planned burns.

a See https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/net-zero-coalition.

Steve Hamburg and Ann Bartuska, Environmental Defense Fund (EDF), shared their motivation for sponsoring the workshop. There is a knowledge gap in current understanding of the extent of wildland fires, their GHG emissions, and the implications for

reaching net-zero GHG emissions. Hamburg shared EDF’s interest in creating a scientific foundation to make decisions about opportunities to reduce GHG emissions from wildfires, particularly wildfires in unmanaged lands. Hamburg charged the participants to think boldly about the wildfire challenge and to explore what is known, where there are knowledge gaps, and a possible path forward built upon a solid foundation of science. Bartuska recognized the importance of highlighting and learning from Indigenous and cultural burning practices as part of the workshop and discussion of the solution space, and noted that the timing of the workshop was shortly before the release of the Wildland Fire Mitigation and Management Commission report (2023), which outlined recommendations to Congress to address the U.S. wildfire crisis.

Workshop Scope

On behalf of the workshop planning committee, Nancy French, Michigan Technological University, provided framing and motivation for workshop discussions. French emphasized the key charge to workshop participants: Identify examples of gaps and opportunities in data and models, and changes in land stewardship, that can inform and enhance strategies to limit wildland fire GHG emissions and associated threats to net-zero emission targets.

Biomass burning is an integral force in the Earth system at the global scale, and fire is a management tool used at local and landscape scales. While smoke from fire can affect air quality and human health, the workshop focused on fire as a source of carbon and other GHG emissions, though air quality and GHG emissions are intertwined. The workshop focused on managed burning (where fires are allowed to burn naturally and only suppressed under defined management conditions), unintentional fires that are then managed, and unmanaged fires, because these fire types have the largest potential impacts on GHG emissions. Biomass burning from sources such as wood gathering, cookstoves, and cropland burning were not the focus and are less significant from the perspective of GHG emissions.

The workshop considered fire as a key factor in the carbon cycle at all scales from global to local and short term to long term. Fire has impacts on the carbon cycle of terrestrial ecosystems at multiple timescales: first, there are direct emissions of smoke; then, there may be delayed emissions as the system adjusts to new conditions; and finally, there is subsequent regrowth and ecosystem changes, which can transform carbon cycling. French explained that ecosystems where recovery post-fire is long—tens to hundreds of years—should be the focus for considering the impact of fire on the global carbon budget.

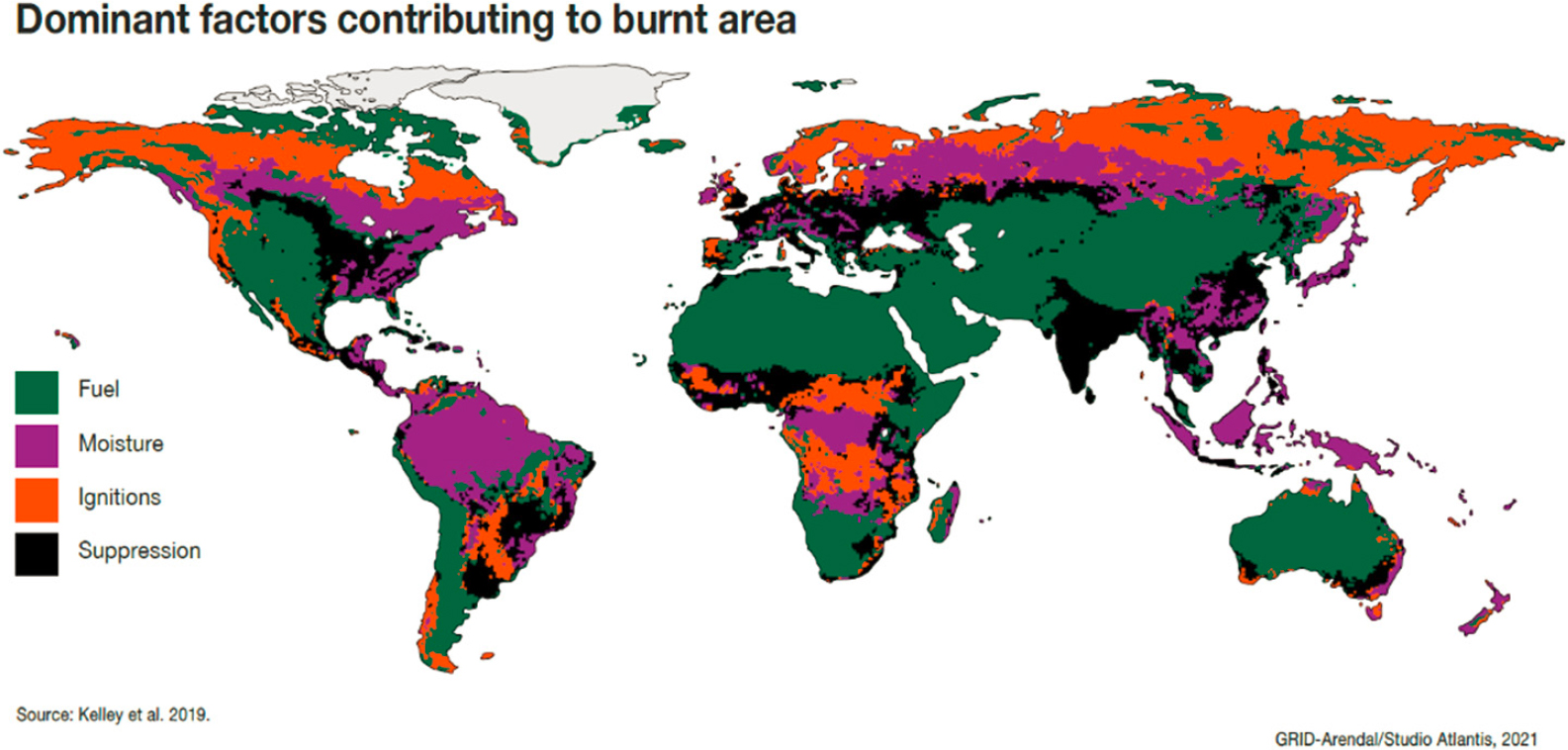

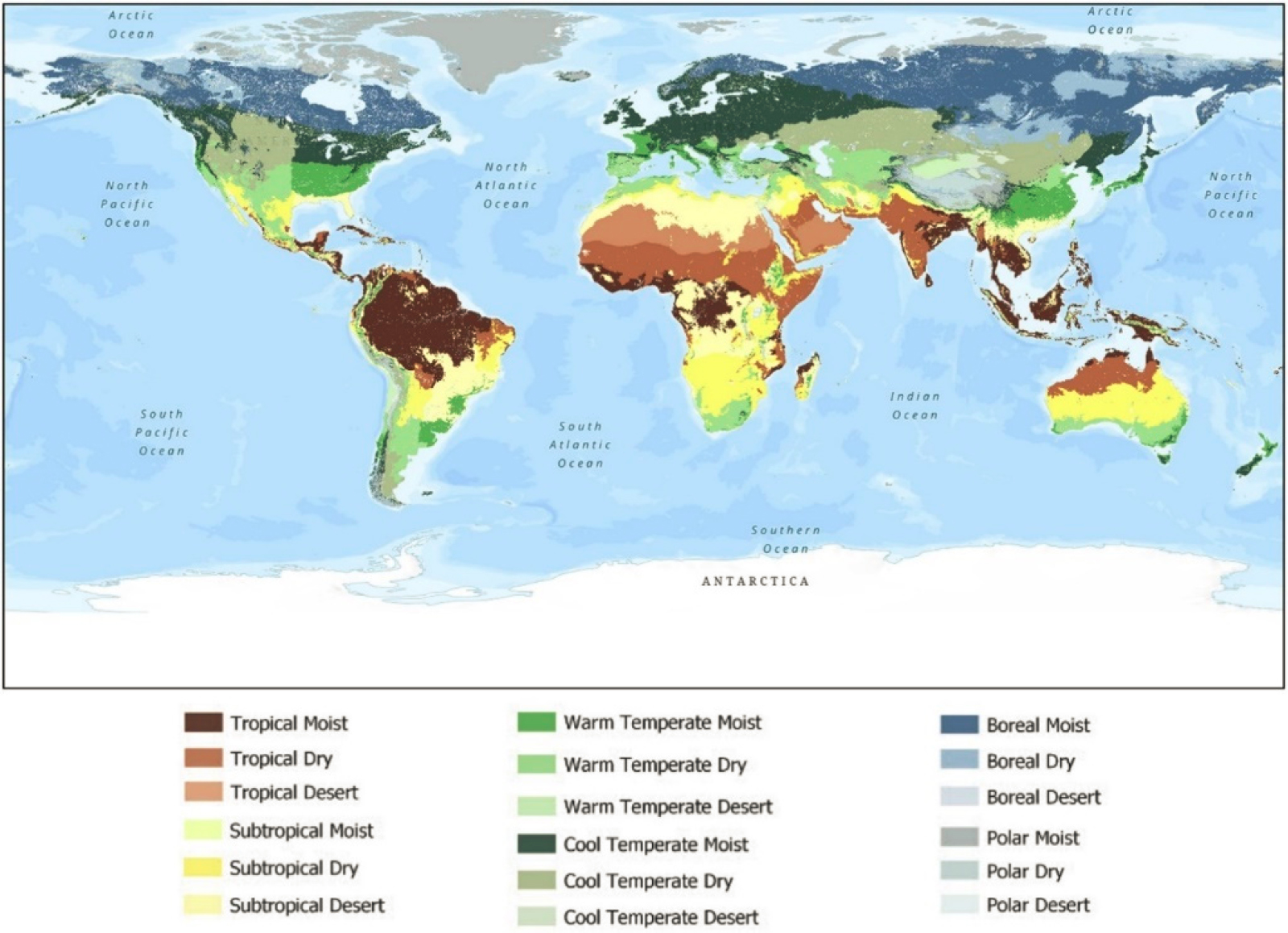

The workshop centered on ecosystems vulnerable to changes in fire conditions and regimes due to present and future direct and indirect (i.e., climate change-driven) human influences. In particular, sessions focused on archetypes of fires in three broad biomes, which each have different main drivers of change (Figures 1 and 2):

- Temperate biomes: Change is due to a combination of climate, historical land use legacies, and current fire and ecosystem management practices;

- Arctic/boreal biomes: Change is dominated by climate (indirect human influence) with direct human influence presently limited, but emerging; and

- Tropical biomes: Change is dominated by economically driven systems and fire management with limited climate influence.

Workshop discussions focused on landscapes where there has been a disruption in fire regime in the past and present, including where fire is common for ecosystem maintenance or landscapes, where historical fire regimes and cultural practices have been disrupted due to colonialism, or other land use forces (Figure 2). Ecosystems where the carbon cycle is being drastically impacted—for example, landscapes where fire is novel, the fire regime is changing, or old carbon stocks are being disrupted—were of particular interest, rather than grassland and savannah landscapes that experience rapid revegetation following fire. French identified the challenge of addressing fires across this broad diversity of biomes because they require regionally differentiated and ecologically appropriate solutions

that account for the biome-specific fire regime, plant and ecosystem adaptations and vulnerabilities, and the legacy of people on the land.