Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Wildland Fires: Toward Improved Monitoring, Modeling, and Management: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: Biomes Vulnerable to Wildland Fires and Implications for Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Biomes Vulnerable to Wildland Fires and Implications for Greenhouse Gas Emissions

The first day of the workshop considered how human activity—through anthropogenic climate change and land use change—have affected fire activity and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions across different global ecosystems. Participants assessed how shifts in baseline fire regimes (e.g., through fire exclusion or inclusion) have perturbed fire activity and the carbon cycle (e.g., introducing fire to ecosystems with old, stored carbon) and the implications of increased frequency and severity of extreme wildfires for GHG emissions. Understanding current conditions of these ecosystems informed workshop discussions about feasible and effective solutions for management. Sessions first introduced conditions in currently vulnerable biomes, and second, considered current opportunities for management.

ROLES OF FIRE IN PRESENTLY VULNERABLE BIOMES AND THE ASSOCIATED NET GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSIONS

Across multiple sessions on the first day of the workshop, speakers introduced the three biomes of focus—temperate, Arctic/boreal, and tropical—and the factors making these ecosystems vulnerable to wildfire and significant emissions of GHGs today and in the future under climate change. Speakers considered the changes in net GHG emissions from fires and the necessary conditions to maintain these ecosystems in a resilient state.

Temperate Biomes

Several speakers provided historical context for the changing role of fire in temperate biomes—particularly in the western United States—and the ways in which the colonial policies of fire suppression have made these systems vulnerable. Using California as an example, Scott Stephens, University of California, Berkeley, noted that pre-1850 (statehood), approximately 1.8 million hectares (ha) burned annually, with about half the area burned coming from lightning and half from Indigenous burning (Stephens et al., 2007). Hugh Safford, University of California, Davis and Vibrant Planet, explained that the current burned area in California does not come close to an average year of area burned pre-1850 (Stephens et al., 2007). The policy of fire suppression over the last century is a major driver of ecological degradation in the state’s ecosystems (Figure 3). Karin Riley, U.S. Forest Service, shared the example of low-elevation ponderosa pine forests in Montana that would have seen fire every 7–25 years prior to colonization. When Indigenous burning was removed as a process on the land, the European forestry model of suppression, which saw fire as a threat to timber resources, became the 20th-century practice of the U.S. Forest Service.

Matthew Hurteau, University of New Mexico, emphasized that restoring the process of ecologically appropriate fire to temperate ecosystems is the key to maintaining stability for both carbon and forest cover. As a forest develops, it accumulates carbon over time until a process such as a high-severity wildfire decreases that live tree carbon. Hurteau introduced the carbon carrying capacity framework (i.e., a system’s stable carbon stock over time) (Figure 4) in which, as long as prevailing climatic and natural process conditions remain consistent, the same amount of carbon will be sequestered over the same period of time. However, shifts in the prevailing climate or natural process conditions can result in temperate systems that store a lesser amount of carbon.

There are broadly two types of fire regimes in temperate forests, both of which are directly and indirectly influenced by humans: (1) climate driven and (2) human and climate driven (Figure 4). In the climate-driven regime, in general, vegetation is unavailable to

burn most years because temperatures are too low or moisture is too high to support combustion, so only during hot, dry years is the system available to burn. In the human- and climate-driven regime, in general, temperate forests are available to burn every year during a fire season, and climate’s effect on vegetation productivity and the amount and connectivity of the fuel present influence how often the system burns. Humans have influenced these regimes for millennia through purposeful ignitions to achieve management objectives—commonly referred to today as cultural burning—illustrating the impacts that fire stewardship has had across many ecosystems historically.

Climate change is altering the flammability of temperate ecosystems. Large fires have been linked to higher temperatures that increase the length of the fire season (Westerling et al., 2006), and a warmer atmosphere impacts the availability of fuel to burn due to increased drying (Abatzoglou and Williams, 2016). Particularly in forest ecosystems, climate change–driven drying is already having an impact on forest area burned. Juang et al. (2022) found that, while moisture once governed the speed of fire, as the atmosphere demands more water from an ecosystem (vapor pressure deficit), it pulls moisture from the system. At the same time, climate change is altering fuel availability—specifically, biomass and its availability to burn in an ecosystem—which can lead to larger energy released when burned (Goodwin et al., 2021).

The dry, historically frequent fire systems have a surplus of fuel because of active fire exclusion for over 100 years, combined with past land use and land management decisions, Hurteau explained. Past land use and land management decisions have pushed these historically frequent fire systems past their carbon carrying capacity, from the standpoint of natural processes, such that there is now potential for significant ecosystem change. Climate change is influencing carbon carrying capacity from a productivity standpoint, and the combination of human influences on management and climate are causing fire-prone systems to carry more aboveground biomass than they are capable of. Safford pointed to the accelerating forest loss to wildfire in California. He noted that the focus of destructive fires has shifted from chaparral landscapes in the south to the forests of north and central California, where forest ecosystems are burning at such large scales and high severity that they are not recovering (Safford et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022). The rapid increase in fire severity in California and the western United States can be explained by variation in fuels, weather, and climate, with fuel accumulation from suppression playing a major role (Safford et al., 2022).

Hurteau explained that achieving a stabilization of carbon would require a reduction in biomass and reintroduction of fire in its appropriate ecological role. While there is a short-term carbon cost to fire restoration work in these ecosystems, dynamic vegetation processes operate on a decadal timescale and large spatial scale. Modeling studies have shown that compared with no management, management actions such as prescribed burns can decrease cumulative fire emissions by modifying the amount of biomass available to burn (Krofcheck et al., 2019). While there is a short-term carbon cost to fire restoration work in these ecosystems, over the long-term these management actions can lead to greater carbon storage by modifying the way fire interacts with vegetation (Krofcheck et al., 2019). Central to restoration of fire in these ecosystems is managing the types and amounts of vegetation and their spatial distribution, Hurteau said.

Arctic/Boreal Biomes

Hélène Genet, University of Alaska Fairbanks, described the ways in which wildfire is a catalyst of change in boreal and Arctic biomes. In the past, wildfire has maintained and promoted ecosystem structure and function across boreal biomes (e.g., Kelly et al., 2013). For example, black spruce forests maintain a thick organic layer to keep soil cool

and moist, which promotes low fire severity and low fire return intervals (Johnstone et al., 2011). Stephens provided another example of the Canadian boreal forest in which about 90 percent of ignitions are from lightning, and historically, the ecosystem would have high-severity fires every 40–150 years and could regenerate. On the other hand, evidence from Indigenous knowledge suggests fire severity was highly variable even within boreal fires (e.g., Lewis and Ferguson, 1988).

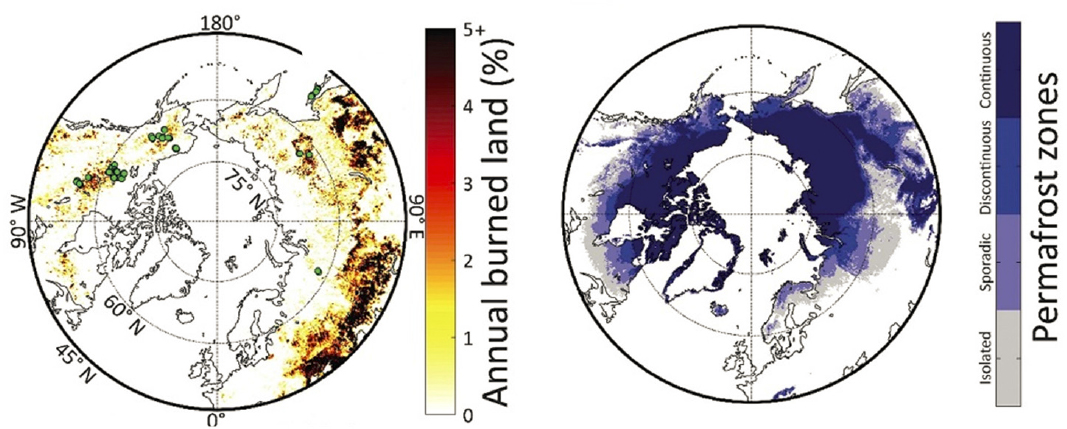

Today, while wildfires in Arctic and boreal regions represent only 1.2–1.6 percent of global area burned, they contribute 6.3–7 percent of global carbon emissions because fires in Arctic and boreal systems occur mostly in permafrost ecosystems that store large amounts of carbon in the soil, explained Genet (Figure 5) (Veraverbeke et al., 2021). In North America and Eurasia in both forest and tundra regions, belowground carbon stocks dominate emissions (Veraverbeke et al., 2021). Thus, large fires in the boreal can have major effects on the regional carbon balance by releasing carbon that has been stored for decades or centuries (e.g., Genet et al., 2018). After fires burn in permafrost regions, permafrost depth increases, increasing the soil carbon available for decomposition, which can increase post-fire carbon emissions (Gibson et al., 2018).

Boreal biomes are warming at least twice as fast as the rest of the world, which increases fire frequency and fire occurrence in the boreal and Arctic (e.g., Kharuk et al., 2022). Changes in the fire regime disrupt the legacy cycle of these ecosystems in which increased-severity wildfires burn more of the system’s thick organic layer, creating an environment for deciduous tree species to dominate the post-fire succession on the landscape.

This shift to deciduous trees, which have more aboveground biomass, can have consequences for the carbon and nitrogen cycle (Melvin et al., 2015) and dampen the fire regime over the medium to long term (Bernier et al., 2016). Increases in fire severity can also accelerate permafrost loss that may not recover even 100 years post-fire (Jafarov et al., 2013). The increases in fire frequency and fire severity will burn the ecosystem’s organic layer, meaning forests will not have enough time to recover the carbon lost during the fire and will begin to lose legacy carbon (Walker et al., 2019).

Stephens pointed to an example in Wood Buffalo National Park in Canada where boreal forests are reburning at frequencies never seen before due to climate change–induced changes to fire regimes. For example, the same area burned in 2004 and again in 2014, killing the regenerating conifer forest and dramatically changing the ecosystem (Figure 6). Canadian forest ecologists and managers are concerned about this potential for type conversion over a large land area, Stephens reported.

Management in the boreal is challenging because boreal forests are adapted to infrequent, high-severity fire. Prescribed burning would kill trees in these forests because they have thin bark and do not resist fire well. One option that Stephens discussed is to increase suppression resources in the boreal regions to reduce fire frequency, but he thought that this would not be successful. Genet mentioned another management option in the managed boreal is to promote more deciduous forest across the landscape to slow the fire regime. However, such a solution would only be successful if the forest and timber sectors are able to adapt and have a market for boreal hardwood.

Genet also identified several potential directions for future research on wildfire in Arctic and boreal biomes: evaluation of long-term effects of wildfire on vegetation, permafrost, and ecosystem carbon dynamics across the boreal and Arctic biomes; representation of drainage conditions and stand characteristics when estimating fire emissions; and representation of ecological shifts associated with changes in wildfire regimes in process-based biogeochemical models. Additional ideas for improved understanding discussed during breakout sessions are summarized in Box 2.

BOX 2

Workshop Participant Ideas to Improve Understanding of Fire in Presently Vulnerable Biomes

Breakout discussions on the first day of the workshop discussed the following: gaps in knowledge of greenhouse gas emissions from fires, uncertainties in fire activity and the carbon budget, and related research areas that could improve understanding:

- Generating data maps of global carbon stocks;

- Improving carbon accounting to include avoided emissions and better classification of emissions as anthropogenic or nonanthropogenic;

- Reducing uncertainties in fuels at the regional, continental, and global scales as well as spatiotemporal variability;

- Improving understanding of post-fire carbon stock recovery over time;

- Improving understanding of feedbacks, including emissions from permafrost thaw, cooling from aerosols, and methane emissions from smoldering emissions;

- Developing a next-generation fuel monitoring system and vegetation mapping, including the three-dimensional structure of fuels; and

- Creating early warning prediction systems that take into account climate and fire weather to predict how much fuel would burn.

This box provides a summary of the breakout discussion. It should not be construed as reflecting consensus or endorsement by the committee, the workshop participants, or the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

Tropical Biomes

Susan Page, University of Leicester, introduced the importance of tropical peatlands for carbon storage and the current vulnerability of peatlands to fire. Roughly one-sixth of global carbon stored in peatlands (100 billion tons) is located in the tropics (Dargie et al., 2017; Page et al., 2011). Tropical peatlands are highly vulnerable carbon pools due

to multiple large-scale changes: rapid land use change, including agricultural land conversion; use of fire as a land clearance tool with the potential to release both above- and belowground fuel loads; introduction of people to ecosystems and resulting intentional or unintentional human ignition of fires; and climate drivers. As an example of land use changes in Southeast Asia, as of 2015, about 50 percent of peatland was occupied by smallholder agricultural areas or industrial plantations, while only 6 percent remained as forest (Miettinen et al., 2016, 2017).

In 1997–1998, during the strongest recorded El Niño and Indian Ocean Dipole in the 20th century, large wildfires burned in Indonesia and spread haze across Southeast Asia. While this event first drew attention to fires on tropical peatlands, peatland fires have become a recurring issue, often (but not always) associated with El Niño events, explained Page. The GHG emissions associated with these fires are significant, for example, exceeding the fossil fuel emissions of Indonesia in 2015.

Climate change has both direct and indirect effects on peatland fire dynamics. Drought is an example of a direct effect in which water tables in drained peatlands will become even lower, exposing a higher fuel load for combustion. Indirect effects include the combination of land use and climate-driven changes that degrade forests and increase fuel availability. There have also been dramatic changes from people using fire purposefully or unintentionally—as a result of land use change—on landscapes that were not previously flammable.

Peat fires are smoldering fires; they are slow moving, low temperature, can persist over time, and are often in remote locations making them difficult to control (Hu et al., 2018). One approach to calculating total fire emissions from peatlands is the conventional burned-area approach (van der Werf et al., 2010). However, estimating emissions from peatland fires is challenging because there are large uncertainties in burned area, peat density, burn depth, and burn heterogeneity, as well as few measurements of emission factors. A “top-down” approach using, for example, radiative fire energy from satellite observations (e.g., Kaiser et al., 2012; Wooster et al., 2005), also presents challenges for quantifying emissions in tropical peatlands, particularly due to limited data availability and few measurements of emissions.

Page summarized the complex landscape of drivers and impacts of peatland fires in remote, tropical regions (Figure 7). To understand the scale and type of emissions, better understanding of the drivers of peatland degradation (e.g., drainage, clearing, conversion, fire history) and peatland characteristics (e.g., chemical, physical, biological) are important.

There is a long way to go to restoring peatlands and reducing the scale of emissions from wildfires. While there have been efforts to restore some degraded peatlands, logging and other activities have introduced drainage canals that are challenging to block, and it is difficult to keep ignition sources out of the landscape. To make progress, successful re-wetting activities—deliberate actions that aim to restore the water table of a drained peatland—together with continuous fire monitoring and fire management are needed, said Page.

Breakout discussions on the first day of the workshop included other important ecosystems that had not been the focus of the workshop thus far. Discussions identified, in particular, nonforested systems (e.g., grasslands, rangelands, woodlands) and other vulnerable ecosystems, including forest clearing and floodplains in the Amazon, Congo, and Sierra Nevada (where there is weakened ecosystem resilience); Mediterranean (where there has been land abandonment); woodlands of India and Southeast Asia; and African savannas, particularly interactions between agriculture and woodland savannas.

MANAGEMENT OF FIRES AND ECOSYSTEMS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSIONS: RECENT PAST AND CURRENT

The final session of the first day focused on present-day management and stewardship approaches for wildland fires and ecosystems and implications of these approaches for GHG emissions. Speakers in this session represented snapshots of practitioner and Indigenous knowledge across different ecosystems and biomes. They described current

understanding of the solution space for land stewardship; stewardship approaches that are and are not working in different biomes; the ways that settler and Indigenous approaches to management have influenced resilience; and the short- and long-term benefits of fire management.

Management in Temperate Biomes

Building on the foundational context for the vulnerability of temperate forests in the western United States, described above, speakers outlined a number of strategies to reverse the decades-long policy of fire suppression that has left these ecosystems vulnerable. Safford argued that instead of focusing on burned area as the metric of successful management in these systems, attention should instead be on the conditions under which fires are burning. In California, fuels in fire-suppressed forests need to be managed to slow or reverse current trends, said Safford. Mechanical fuel reduction, or thinning, is challenging because most federal land in the western United States—45.9 percent of the land in the 11 coterminous western states is federally owned—is too steep, distant, or protected to permit mechanical operations by heavy forestry equipment. Additionally, markets for nontimber forest products generated by thinning are underdeveloped. Hand thinning, in which smaller handheld tools are used on smaller diameter materials, can be an effective add-on after mechanical thinning or before prescribed burning, however, hand thinning generates woody residue. While moving fine, small-diameter fuels offsite to be repurposed is an important goal, the sawmill and other wood products industries, particularly in the western United States, have collapsed or been underdeveloped, so there is not sufficient capacity to utilize these fuels.

In the western United States, Safford said, fire itself will be the arbiter of most fuel treatment. Proactive management of how fire operates on the landscape on a large scale can reduce fire risk and increase ecosystem and community resilience. In the absence of pre-fire management, most federal land will be burned by wildfires under current management practices. Proactively allowing fires occurring under benign conditions to burn, instead of extinguishing them, is the only treatment option for 60–70 percent of the federal forested land, Safford explained.

Stephens shared a success story in the Illilouette Creek Basin of Yosemite National Park where lightning fire has been allowed to burn unabated for the last 50 years (Boisramé et al., 2017; Collins et al., 2009; Stephens et al., 2007, 2021). This research demonstrated that managed wildfire could restore a formerly fire-suppressed temperate or frequent fire forest to a functioning fire regime with the capacity to self-regulate (Figure 8).

Riley reiterated that fire needs to be a part of successful fuel treatments, including broadcast burning—burning the whole area—or pile burning, which may be less effective. Modeling can be a useful tool for fire managers to better understand the location and size of future fires. Riley provided the example of using a burn probability map together with datasets of carbon estimated from models to quantify projected emissions from litter, duff, downed woody debris, and standing trees.

Stephens offered hope for solutions to reduce fire hazard and promote forest restoration in temperate forests. He emphasized that Indigenous stewardship, which has existed for millennia, has large potential if Indigenous people choose to partner with western scientists (Box 3). Also critical to future management is a workforce that can scale up to work on management year-round, rather than a seasonal workforce built for fire suppression. Stephens noted that in the United States, a true partnership with Indigenous people to manage fire in an ecologically appropriate way is a strategy that has not yet been tried but could be a potential solution. In temperate systems, cultural burning, prescribed burning, and active management of wildfire in appropriate areas can all be done in ways that are complementary to cultural activities.

BOX 3

The Stewardship Project: A Partnership of Indigenous Knowledge and Western Science

Scott Stephens, University of California, Berkeley, and Don Hankins, California State University, Chico, introduced the Stewardship Project,a a 50-50 partnership between Indigenous communities and western scientists to produce fire policy recommendations for state and federal governments. Hankins explained that the effort is focused on enabling forest resilience through revitalizing the principles of active stewardship and Indigenous leadership. The project is centered on four key elements: tribal rights to steward, workforce and capacity development, regulatory realignment, and public land fire management areas. This effort is complementary to the Wildland Fire Mitigation and Management Commission that released their report in September 2023 (Wildland Fire Mitigation and Management Commission, 2023), with workforce development being a strong area of overlap, Stephens explained.

a See https://climateandwildfire.org/cwi-projects/the-stewardship-project.

Management in Arctic/Boreal Biomes

Amy Cardinal Christianson, Parks Canada, centered her remarks on the impacts of fire on people in Canada, specifically, on the disproportionate impacts on Indigenous people. Wildfire evacuations are one metric for capturing impacts on people, and Christianson showed that while 5 percent of the Canadian population identifies as Indigenous, 42 percent of wildfire evacuation events in Canada have been of communities with greater than 50 percent Indigenous populations (Figure 9). Communities are evacuated due to both direct threats from fire as well as evacuations solely due to smoke and poor air quality. The same communities have been evacuated, for example, up to seven times in the last 40 years, and almost all these communities with repeat evacuations are Indigenous (Figure 9).

Christianson explained that Indigenous people in the boreal have always “sought to replace fires of chance with fires of choice” (Pyne, 2007) using fire and working with lightning to clean the land to achieve specific cultural objectives. Indigenous practices have been removed from the landscape of the boreal, and this cultural severance has had major implications. The path forward, Christianson argued, should center Indigenous-led fire management in their own territories and dedicated resources to employ Indigenous people in the boreal, rather than primarily partnerships with agencies that want to learn from Indigenous knowledge (Christianson et al., 2022; Maclean et al., 2023). The northern territories of Australia are an example of where Indigenous fire management has reduced emissions.

Reflecting on opportunities to learn from Indigenous practices, Christianson shared that Indigenous people in the boreal work on a circular calendar based on observations of the land around them, which is a practice highly adaptable to climate change. The challenge, however, is how to start reintroducing these practices after the forest has been so mismanaged, where the historical fire practices that Indigenous people used could not be done safely today.

Dan Thompson, Canadian Forest Service, explained that the 2023 fire season in Canada was by far the worst on record nationally, leaving the entire country impacted by severe fire. The 2023 fire season reflected the forest environment in Canada and was largely a consequence of lightning rather than human ignitions. In September 2023, at the time of the workshop, less than 40 percent of fires were being actively suppressed because the fires were too large and too remote.

Forest conversion to deciduous species is one of few management and mitigation strategies feasible on a large forest scale, Thompson said. After fire, young forest, especially broadleaf, is commonplace from resprouting and air-transported seeds; these forests are one of the few natural negative feedbacks to dampen an otherwise accelerating fire regime in the boreal. Young broadleaf is a consequence of natural succession in the Canadian boreal and burns at 12–25 percent of the frequency (Bernier et al., 2016), has lower landscape-level flammability (Erni et al., 2018), and directly emits approximately one-third the direct emissions of smoke and GHGs, compared to the Canadian forest as a whole. Fire propagation modeling suggests that stitching together recent wildfire scars with prescribed burning, particularly in areas changing from spruce to less flammable broadleaf, can start

to have landscape effects that could impact fire probability, even within old conifer forests. Thompson also noted that some prime areas where there has been the most fire suppression over the last 75 years is in the roughly 40 kilometers around dispersed communities in northern Canada that could, at the local scale, be a place to start to reintroduce fire and conversion to a less flammable landscape.

Management in Tropical Biomes

Bibiana Bilbao, Universidad Simón Bolívar, described the steady increase in active fires across South America over the last decade in areas where there is land use change from deforestation and hotter and drier climates (Anderson et al., 2022). In response to extreme conditions and the occurrence of megafires—for example, in the Amazon—most countries in South America have adopted zero-fire policies that focus on avoiding fire and directing resources toward fire brigades and technical support. Not only are these methods not effective, but also the $5 billion per year that the United States spends to fight forest fires is not feasible for countries in Latin America. Further, Bilbao explained that these zero-fire practices come from colonization, excluding local Indigenous knowledge and practices that allowed cultures to survive and preserve a highly diverse continent.

Bilbao shared a new paradigm of integrated fire management with an intercultural vision, drawing on experiences working with the Pemón Indigenous peoples in Canaima National Park, Venezuela, in northern Amazonia. The Pemón use fire in their daily practices for agriculture and hunting, as well as to protect forests from fires that start in savanna areas. Bilbao implemented a collaborative, long-term experiment to simulate traditional Pemón fire methods by burning a series of plots over different time periods (Bilbao et al., 2009, 2010, 2017, 2021, 2022). The technique of creating a mosaic of patches with different fire histories, known as patch mosaic burning (PMB), can be used as a firewall to reduce the risk of hazardous wildfires, particularly in the savanna–humid tropical forest transition (Figure 10). This technique imitates practices used by the Pemón Indigenous Peoples for centuries to sustainably manage savanna–forest boundaries and protect the forests that represent their principal source of food resources and spiritual reasons. If fire is excluded from these savanna areas, dried fuel accumulates, increasing the risk of wildfires spreading into the forest. Bilbao also emphasized the importance of traditional management in the context of climate change to reduce wildfire risk. In addition to incorporating Indigenous knowledge and participation in new intercultural paradigms of fire management, it is equally crucial to honor Indigenous cultural heritage and acknowledge Indigenous peoples’ capacity to evolve and adapt their practices to new conditions, Bilbao explained.

Cynthia Fowler, Wofford College, drew attention to the subset of GHG emissions from subsistence economies, known as survival emissions. Fowler shared that for islander communities in the Indian Ocean, landscape burning is essential for managing subsistence regimes, acquiring adequate nutrition, experiencing the world in meaningful ways, expressing cultural identities, and exercising self-determination. While GHG emissions from Indian Ocean nations have been increasing over the past two decades, some of the emissions are generated while meeting basic needs, including from agriculture, animal husbandry, and biomass burning. Survival emissions can be difficult to measure because they are often dispersed, small, informal, and unpublicized.

One example of these systems is the Indian Ocean island, Sumba, where savanna and garden fire environments are managed through pasture livestock, weeding, planting, harvesting, and burning. Sumba has two overlapping anthropogenic fire regimes in which there is fast burning of fine fuels, which produce fewer emissions. Relative to total GHG

emissions from agriculture in Indonesia, for example, survival emissions from burning crop residue contributes few emissions while enabling livestock husbandry and food production. Fowler argued that these fire regimes are worth studying to understand the human and ecological conditions where management produces fewer emissions.

Fowler pointed to the need for local studies on biomass fires in diverse environments. She argued that assessing the contribution of survival emissions from rural, Indigenous, and agropastoral communities relative to anthropogenic emissions from other communities around the world raises questions about which parts of society are vulnerable to climate change, and which parts are responsible for reducing emissions. Fowler underscored the high stakes for Indigenous islanders and need for their leadership in research projects as well as policy and management recommendations stemming from such studies.

Examples of Additional Management Opportunities from Breakout Discussions

Breakout discussions highlighted additional management opportunities across different biomes. Discussions reiterated workshop themes about the importance of partnering with Indigenous communities who have been stewards of fire on the landscape for millennia. Participants emphasized the importance of considering fire ecology in the local context and history of an area, and considering consequences of management policies on water, biodiversity, and community resilience.

Discussions also highlighted locations with a mix of fire severity—for example, the western United States—as a potential entry point on the landscape for continued management, including prescribed burning and fuels management. Rapid detection tools to target fire suppression in vulnerable ecosystems with rapidly changing fire regimes and deep ancient carbon could be a potential strategy, together with prescribed burning, fuels treatment, and cultural burning. Another discussion highlighted strategic pre-fire planning, or potential operational delineations, to design fire response strategies before fire in collaboration with local interested and affected groups.