The State of the U.S. Biomedical and Health Research Enterprise: Strategies for Achieving a Healthier America (2024)

Chapter: 1 Introduction

1

INTRODUCTION

The U.S. biomedical research enterprise—defined for this Special Publication as individuals and organizations that conduct basic research, applied research, and experimental development as well as the pharmaceutical industry, health care, and public health (see Box 1-1)—contributes to the health of the nation, advances in biomedical and health sciences, and the U.S. economy.

The U.S. biomedical research enterprise has historically been a global leader, and its impacts are far reaching. Beyond health, biomedical research discoveries contribute to advances in agriculture, energy production, and environmental remediation, among other areas. Biomedical research is also an economic engine—generating jobs, innovations, and new technologies—and provides expertise to support governmental priorities during public health crises. Since its inception more than 80 years ago, the U.S. biomedical research enterprise has delivered on its promise to improve human health and has contributed greatly to America’s knowledge capital.

However, due to emerging and escalating health crises, global growth in biomedical research that may reduce America’s leadership in the field, and existing structural issues that threaten the enterprise’s effectiveness and efficiency, attention on how to bolster and streamline the enterprise is needed, which is the focus of this Special Publication.

THE IMPACT OF THE U.S. BIOMEDICAL RESEARCH ENTERPRISE

One way to determine how well the U.S. biomedical research enterprise is performing in terms of improving human health is to identify the top causes of mortality in the United States, the disease areas and National Institutes of Health (NIH) institutes with the highest appropriation levels, and disease prevalence and

BOX 1-1

Definitions of Types of Research Included in the U.S. Biomedical Research Enterprise

- Basic research is “experimental or theoretical work undertaken primarily to acquire new knowledge of the underlying foundations of the phenomena and observable facts, without any particular application or use in view.”

- Applied research is “original investigation undertaken in order to acquire new knowledge. It is, however, directed primarily towards a specific, practical aim or objective.”

- Experimental development is “systematic work, drawing on knowledge gained from research and practical experience and producing additional knowledge, which is directed to producing new products or processes or to improving existing products or processes.”

SOURCE: NSF, 2018.

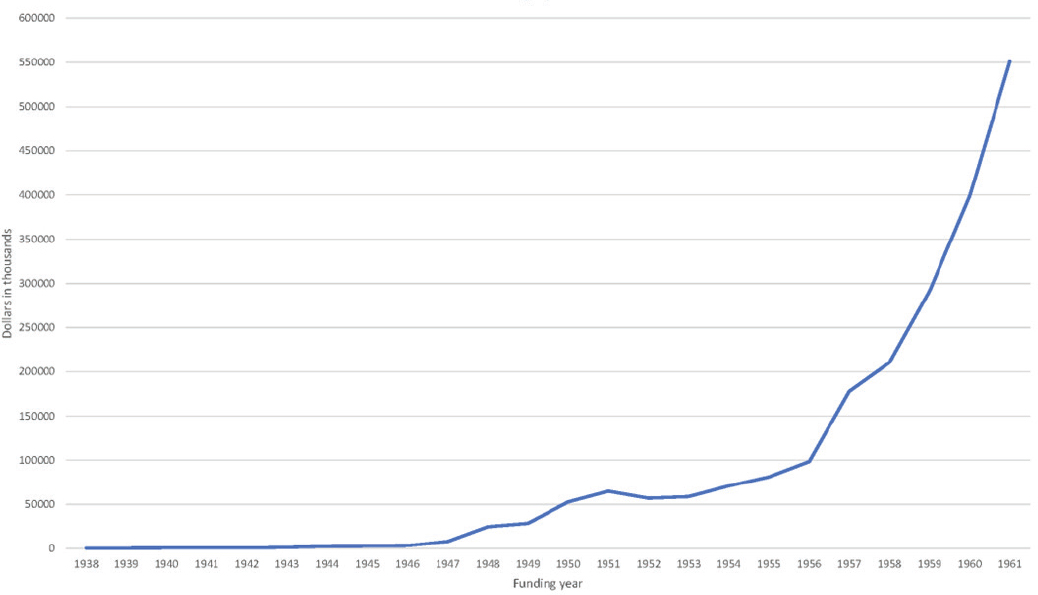

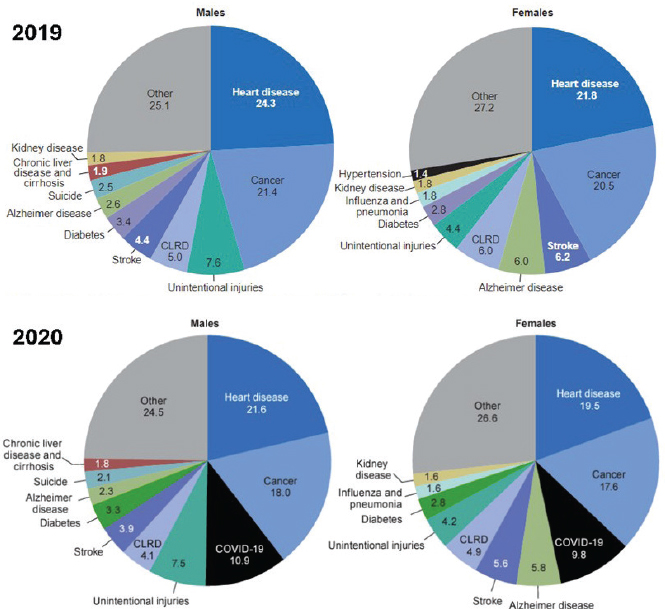

mortality over time. The top two causes of death in the United States in 2019 and 2020 were heart disease and cancer, respectively (see Figure 1-1). HIV/AIDS, although not a current leading cause of death, is a disease that the United States has worked to ameliorate for decades.

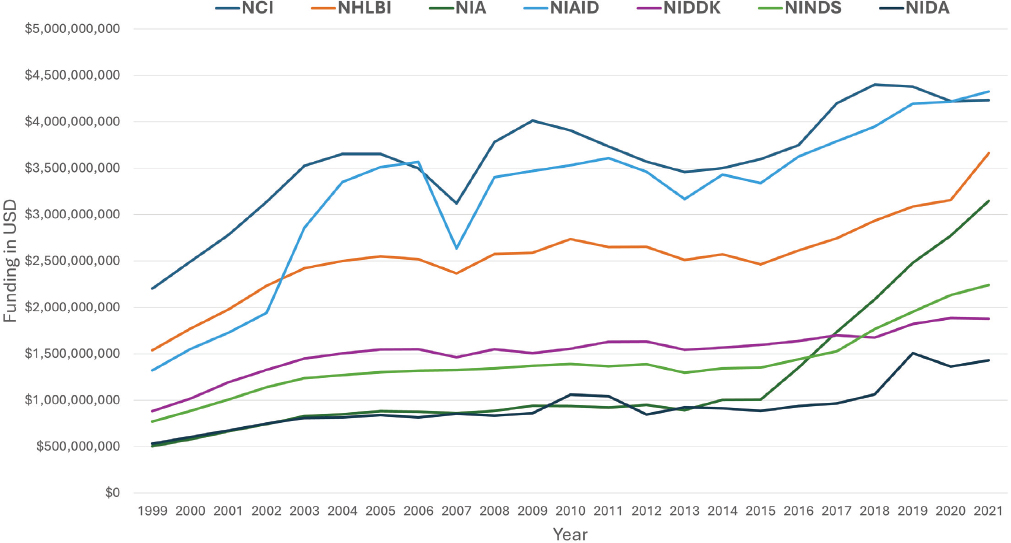

Relatedly, three of the consistently highest-funded NIH institutes and centers are the National Cancer Institute (NCI); the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) (see Figure 1-2).

The authors of this Special Publication reviewed sufficient data to conclude that significant amounts of sustained federal funding focused on a specific disease or disease type—the primary vehicle by which the U.S. biomedical enterprise funds discovery research—have led to reductions in morbidity and mortality in that disease or disease type. Accordingly, after decades of federal investment in research, education, and prevention, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and HIV/AIDS are no longer death sentences and can be managed as chronic conditions—testaments to the success of the U.S. biomedical research enterprise.

NOTES: CLRD = chronic lower respiratory disease. Values show percentage of total deaths.

SOURCES: Curtin et al., 2023; Heron, 2021.

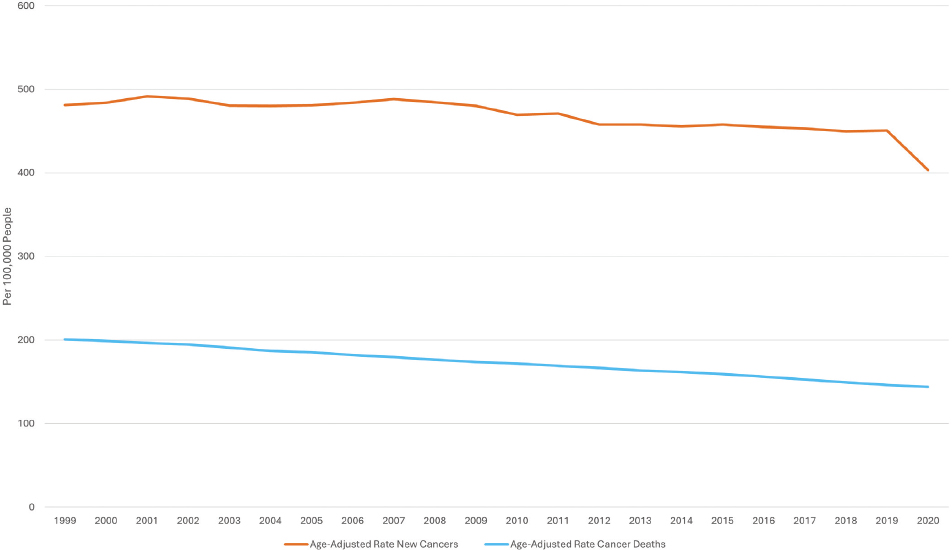

Cancer

Overall, cancer deaths and new cancer cases in the United States have declined in the past two decades (see Figure 1-3). Cancer deaths have declined by 33% since 1991, leading to an estimated 3.8 million more cancer survivors (American Cancer Society, 2023). Many cancers can now be treated without surgery and some—including breast, melanoma, prostate, testicular, and thyroid—have 5-year survival rates above 90% (Kandola, 2023). The 5-year survival rate for all cancers was 49% in the mid-1970s and rose to 68% in 2023 (City of Hope, 2023).

Focused federal attention on addressing cancers began with the 1971 National Cancer Act—legislation that represented America’s commitment to the “war

NOTE: NCI = National Cancer Institute; NHLBI = National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; NIA = National Institute on Aging; NIAID = National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; NIDA = National Institute on Drug Abuse; NIDDK = National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; NINDS = National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

SOURCE: NIH, n.d.b.

NOTE: The orange line represents the number of new cancer cases per 100,000 individuals and the blue line represents the number of cancer deaths per 100,000 individuals.

SOURCE: CDC, 2024d.

on cancer” and allowed for strategic planning; increased funding; and additional researchers, centers, training programs, contracts, and advisory committees to support the increased scope of cancer research (NIH NCI, 2021). The National Cancer Act led to the creation of the NCI Cancer Centers Program, which recognizes high-performing centers utilizing transdisciplinary research (NIH NCI, 2024). Today, 72 NCI-designated cancer centers around the country receive federal funding to perform cancer research and conduct clinical trials to test new cancer treatments (NIH NCI, 2024). In addition to advancing prevention, diagnosis, and treatment, these NCI-funded centers also train the next generation of researchers and clinicians. Collectively, federal funding through NCI that supports education, early screening, research, prevention, and treatment has demonstrably reduced cancer mortality and cancer incidence in the United States.

Cardiovascular Disease

Cardiovascular disease includes coronary heart disease, stroke, high blood pressure, and heart failure, among other conditions (IOM, 2011). Heart disease mortality year over year per 100,000 fell 56% from 307.4 in 1950 to 134.6 in 1996, and stroke rates fell 70% in this same period (Mensah et al., 2017).

Many significant biomedical advances have led to the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease, including (examples from Mensah et al., 2017):

- The Framingham Heart Study (1948–current), which identified high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and male gender as major risk factors for cardiovascular disease (NIH NHLBI, n.d.);

- The first coronary artery bypass surgery, performed in 1960 (Konstantinov, 2000); and

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of statins in 1987—angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and calcium channel blockers—which are effective drugs for controlling cholesterol and blood pressure and can reduce the incidence of acute cardiovascular disease (Junod, 2007).

NHLBI was created in 1948, after legislation signed by then-President Truman in response to a dramatic increase in American deaths due to cardiovascular disease (NIH NHLBI, 2011). The Framingham Heart Study, in particular, continues to produce valuable data informing current research, as the longitudinal study is now examining the third generation of participants—over 15,000 individuals in total (NIH NHLBI, n.d.). Since its inception, NHLBI has been one of the highest-

funded NIH institutes, and this funding has been used to support research that has directly led to the significant reductions in morbidity and mortality described above (NIH OB, n.d.).

HIV/AIDS

HIV/AIDS has claimed 700,000 U.S. lives since the beginning of the epidemic in 1981, but HIV infection can now be largely prevented and managed as a chronic condition (KFF, 2021). In 2019, the death rate due to HIV/AIDS was 1.4 per 100,000—a reduction from the highest point of 16.2 per 100,000 in 1995 (Walker, n.d.). In addition to significantly reducing the death rate due to HIV/ AIDS infection, 50 drugs are now available for managing HIV levels—compared to just 1 in 1987 (FDA, 2019; HIVinfo.NIH.gov, 2023).

There were few effective therapies for AIDS in the late 1980s, but the Health Omnibus Programs Extension was passed in 1988 and extended in 1993, establishing the Office of AIDS Research at NIH and leading to a strategic plan, budget, and coordinated research around HIV and AIDS (NIH OAR, 2023). Due to the focused effort of the Office of AIDS Research, significant federal funding, and the participation of many other NIH institutes, protease inhibitors were discovered in 1996, which extend the lives of people living with HIV/ AIDS (NIH, 2015). Researchers at NIAID also contributed to developing a wide variety of antiviral drugs, as “HIV mutates rapidly and some people can’t tolerate certain drugs,” so “cocktails” of medications are necessary to treat people living with HIV/AIDS (Collins and Fauci, 2010). More recently, better access to HIV testing, increased access to treatment, improved education about HIV/AIDS, and the use of pre-exposure prophylaxis—or PrEP—have led to further declines in infection rates (Park, 2023).

Basic Science and Future Discoveries

The steady advance of biomedical research has also enabled many critical discoveries that would have been impossible without decades of quiet and unpublicized research and funding. Most notably, years of basic science underpinned the unprecedented rapidity in developing safe and effective vaccinations against COVID-19. The fundamental research in mRNA technology that served as the basis for the platforms that ultimately produced effective vaccines was performed before 2000 (WHO, 2023a). These types of discoveries—often unheralded by the public—coupled with effective public–private partnerships resulted in millions of lives saved globally (No author, 2022a). This is just one example that illustrates

the continued promise of the U.S. biomedical research enterprise in reducing mortality, if appropriately funded and coordinated.

HISTORY AND CURRENT STATE OF THE U.S. BIOMEDICAL RESEARCH ENTERPRISE

The path to the U.S. biomedical research enterprise that achieved the successes outlined above has been winding. The structure of the enterprise was established in the 1940s under President Roosevelt’s direction with the creation of the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) to leverage and coordinate scientific research for military purposes. The work of the OSRD led to scientific advances such as the creation of radar and the mass manufacturing of penicillin to treat infectious diseases (Hourihan, 2020). On the heels of the Second World War, President Roosevelt asked Vannevar Bush—a mathematician, electrical engineer, and then-director of OSRD—to propose how the United States could leverage the wartime research and development (R&D) effort during peacetime. Bush’s report, Science: The Endless Frontier, outlined a central role for the government in developing scientific talent, funding basic research in institutions of higher education, and supporting new scholarships and fellowships to ensure that talent would not be prevented from entering the field by financial hardship (Bush, 1945). Bush’s recommendations led to the creation of the National Science Foundation (NSF)—an organization dedicated to funding basic research (NSF, n.d.). Bush’s bold blueprint for American scientific research laid the foundation for decades of innovation and U.S. leadership in science, technology, and health care.

In parallel, a growing “citizen science” movement led by advocates and philanthropists such as Mary Lasker and Florence Mahoney helped promote government-sponsored medical research and the creation of NIH (Harman and Dietrich, 2018). At the time, many scientists opposed government involvement in research. Lasker, however, famously argued, “if you think research is expensive, try disease,” in lobbying for the U.S. government to play a central role in supporting research to proactively shoulder some of the cost burdens of illness (Haley, 2022). In response to these efforts, the 1944 Public Health Service Act consolidated previously disparate efforts in medical research under the single administrative structure of the National Institute of Health (the predecessor to the National Institutes of Health)—including the previously established National Cancer Institute (NIH, 2024a). Beginning in 1946, Lasker and Mahoney pivoted to lobbying for NIH to expand to include multiple institutes focusing on different aspects of health, resulting in the Omnibus Medical Research Act in 1950, which established the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Blindness and

the National Institute of Arthritis and Metabolic Diseases and opened the door for the creation of other institutes, including the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in 1955 (NIH, 2024a). The National Heart Institute was established separately in 1948 (NIH, 2024a). Between 1945 and 1961 NIH congressional appropriations increased 150-fold to $450 million, reaching approximately $1 billion by the late 1960s (NIH OB, n.d.). By 1960, the United States accounted for approximately 69% of all global scientific R&D, and the rest of the globe combined contributed the remaining 31% (CRS, 2022). See Figure 1-4 for a visual trend of NIH funding between 1938 and 1961.

In 2005, in response to growing concerns about declining U.S. investment in research and higher education and the competitiveness of U.S. businesses within the global market, the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources and the House Committee on Science asked the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to identify and prioritize 10 top actions that could enhance the science and technology enterprise. The resulting consensus study, Rising Above the Gathering Storm: Energizing and Employing America for a Brighter Future, was published in 2007 and updated in 2010 (NAS et al., 2007, 2010). The committee asserted that “innovation, largely derived from advances in science and engineering,” is a primary driver of the U.S. economy (NAS et al., 2010). However, the 2007 report also noted two potentially troubling facts—that federal sources funded 60% of U.S. R&D in 1965 but dropped below 30% by 2002, and that in many science and engineering fields, 38% of those receiving PhDs from American universities were foreign scholars (NAS et al., 2007).

The 2007 report informed and helped establish the America COMPETES Act of 2007, which authorized $33.6 billion in appropriations and a 10.4% funding growth rate for a projected 7-year doubling of the NSF and the Department of Energy’s Office of Science budgets (CRS, 2015). The Act also authorized, for the first time, the Advanced Research Projects Agency–Energy, which “advances high-potential, high-impact energy technologies that are too early for private-sector investment” (ARPA-E, n.d.). Unfortunately, the Act was not fully funded or implemented (CRS, 2015).

In 2015, Hamilton Moses III and colleagues published a special communication in JAMA that called for “new investment … if the clinical value of past scientific discoveries and opportunities to improve care are to be fully realized” (Moses et al., 2015). The authors argued that research conducted by U.S. academic medical centers—often funded by federal monies—remains the cornerstone of innovation and advancement of new therapeutics, devices, and procedures and represents the hallmark of what makes U.S. research distinct from that of other nations.

Advent of Precision Medicine: A Major Milestone in the History of the U.S. Biomedical Research Enterprise

The Human Genome Project (HGP), improvements in computational biology, and the availability of genomic data have recently enabled researchers to improve their ability to predict the combined effects of many gene variants that make up an individual’s genome and calculate the likelihood of developing certain diseases, how severe that disease will be, and how quickly it might progress. These improvements have led to increasingly individualized care for each patient—broadly known as precision medicine—which holds great promise for improving population health.

HGP was an international effort led by the United States to decode the entire human genome, and has, since its inception, continued to change health and medicine (NIH NHGRI, 2024). HGP—launched in 1990, completed in 2003, and funded by the U.S. federal government—provided the first comprehensive map of all the genes in the human genome, which enabled researchers to identify molecular mechanisms underlying disease in individuals, deconstructing the traditional “one-size-fits-all” approach to medicine (NIH NHGRI, 2024). This information will, ideally, lead to a new approach to health care that can provide each patient with a treatment plan tailored to their disease, information on their risks of developing certain diseases, and guidance on what could be done to delay or mitigate disease. While each person’s genome holds hereditary information about their risks for certain conditions, the social determinants of health—including where people are born, where they live and work, and other non-medical factors—also contribute to an individual’s overall health status (Chelak and Chakole, 2023). All these data will be critical for realizing the promise of individualized approaches to maintaining a person’s best health.

Although researchers will continue to translate genomic knowledge into clinical practice for decades to come, many discoveries from HGP have already had far-reaching impacts. These early advances have led to a better understanding of genetics, genomics, and disease; the development of new diagnostic and therapeutic strategies; and new models for data sharing. The following list describes some paradigm-shifting early advances:

- Polygenic risk scores—a predictive likelihood of developing certain diseases—have been calculated for hypothyroidism, hypertension, type 1 and 2 diabetes, breast cancer, prostate cancer, testicular cancer, gallstones, glaucoma, gout, atrial fibrillation, high cholesterol, asthma, basal cell carcinoma, malignant

- Much like the tests for identifying BRCA1 and BRCA2—genetic variants that signal a higher risk for developing breast cancer—researchers have leveraged genomic information to develop genetic tests for other inherited conditions. In 2012, a total of 607 genetic tests were available in the United States—in 2022, a total of 51,803 genetic tests were available (Halbisen and Lu, 2023).

- Researchers are also using their detailed knowledge of gene sequences—derived from HGP—alongside clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) gene editing to potentially correct gene defects and ameliorate disease. In September 2023, a clinical trial to treat acute lymphoblastic leukemia with a genetically engineered chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy began, and in May 2024, the first patient in the United States received a gene therapy to hopefully cure sickle cell disease (Beam Therapeutics, 2023; Kolata, 2024).

- Whole tumor sequencing of cancer patients has led to The Cancer Genome Atlas, which helped identify the most commonly mutated genes that appear to accelerate disease (NIH NCI, n.d.a). The Atlas also enables researchers to identify rare mutations. This collection of data has helped identify targets for developing new drugs and highlighted genetic variants that indicate how well certain drugs will work.

melanoma, and heart attack (Lello et al., 2019). These scores can inform treatment decisions by identifying people with high genetic risks of developing disease—enabling earlier intervention—and identifying individuals who may not respond to certain drugs and will require differential treatments (Lello et al., 2019).

THE U.S. BIOMEDICAL RESEARCH ENTERPRISE IS AN ENGINE FOR THE U.S. ECONOMY

When speaking about the “value” of the U.S. biomedical research enterprise, a healthy nation is the most desirable outcome. However, the authors of this Special Publication also believe that financial growth will follow as health improves. Healthier people are more productive, earn more, and live longer (Braveman et al., 2018). The longer people live, the more they earn, and the more they can save and increase capital. The lifetime potential contribution per person in the United States is $1.5 million in productivity (Grosse et al., 2018). Public health studies of low-income countries have shown that a 10% increase in life expectancy at birth corresponds to a 1% increase in annual gross domestic product (GDP) per capita growth in 5 years and 0.4% in additional growth over 35 years (Bloom et al., 2020).

The association between reducing mortality and improved economic impact is not just an American phenomenon. An economic analysis of health and labor productivity in Australia, Denmark, Finland, France, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom found that a 10% increase in adult survival during their working years would lead to a 6.7% increase in productivity per worker and an increase of 4.4% GDP per worker (Weil, 2007).

Closer to home, an analysis of the Blue Cross Blue Shield Health Index also shows a strong relationship between health and economic performance. The Index comprises deidentified annual data from 43 million Blue Cross Blue Shield members—not including those insured by Medicaid and Medicare—their health status related to more than 390 health conditions, and medical and pharmacy claims data (BlueCross BlueShield, 2024). An analysis by Moody’s reveals that U.S. counties with the highest health scores—defined by the ratio of “expected remaining healthy years of life divided by the number of years that an individual would have under optimal health”—had average incomes that were nearly $4,000 higher than the national average, and the GDPs of the counties themselves were almost $10,000 higher than the national average (White and Ozimek, 2016). The analysis also found that low unemployment rates are associated with higher health scores (White and Ozimek, 2016). Counties with average health scores in the 99th percentile—with 100% being the highest possible health score and 0% being the lowest—are associated with an increase in average annual pay of $5,302 and a 0.6% decline in unemployment (White and Ozimek, 2016).

The U.S. biomedical research enterprise also contributes directly to the U.S. economy. NIH-funded discoveries comprise much of the foundation of the enterprise, contributing $69 billion to America’s GDP and supporting 7 million jobs (NIH, 2023a). NIH-funded discoveries also regularly lead to new drug development, providing a 43% return on public investment, per data spanning from 1980 to 2005 (Azoulay et al., 2019). The $37.81 billion in extramural research support provided by NIH for fiscal year 2023 directly and indirectly supported more than 412,000 jobs nationally, producing new economic activity across all 50 states and the District of Columbia (United for Medical Research, 2024).

The U.S. biomedical and pharmaceutical private sector generated more than $1.4 trillion in economic output in 2020, which brought in $76 billion in tax revenues (PhRMA and Teconomy Partners LLC, 2022). This sector employs more than 903,000 individuals directly and supports, indirectly, an additional 3.5 million jobs (PhRMA and Teconomy Partners LLC, 2022).

Intangible capital—including data, patents, copyrights, and other non-physical capital—has increased over the past several decades and has grown to be

increasingly important in valuations of the U.S. biomedical research enterprise. Ståhle and colleagues estimate that intangible capital accounts for 45% of the global GDP and as much as 70% of the U.S. GDP (Ståhle et al., 2015).

There is tremendous value in a healthy population, and this value can be approximated but not truly measured. However, existing data clearly show that investing in individual and population health does improve economic strength. In the United States, strong historical investment in the biomedical research enterprise has improved health and reduced mortality. It follows that strong investments will ensure continued health and economic prosperity.

WHY DOES THE U.S. BIOMEDICAL RESEARCH ENTERPRISE NEED ATTENTION IN 2024?

Despite the successes outlined above, issues have arisen that require the renewed attention of the U.S. biomedical research enterprise—and to the function and structure of the enterprise itself. These issues include increasing competitiveness from other nations in terms of R&D, scientific advances, and funding; emerging and intensifying health threats that require the use of convergence science in brand new ways; and existing and historical structural issues within the enterprise that prevent its utmost effectiveness, including strategy, workforce, health equity, and funding. This Special Publication outlines these issues, why they are so critical, and what actions can be taken in the near and medium terms to address them.

The health challenges facing the United States are no more complex than those we have made progress in treating—the difference is how far biomedical research has advanced. The artificial intelligence and health technology revolution, combined with major advances in fields such as -omics biology and precision medicine, have fundamentally changed how medicine is studied and practiced. To advance in parallel, the U.S. biomedical research enterprise itself needs to grow and change.

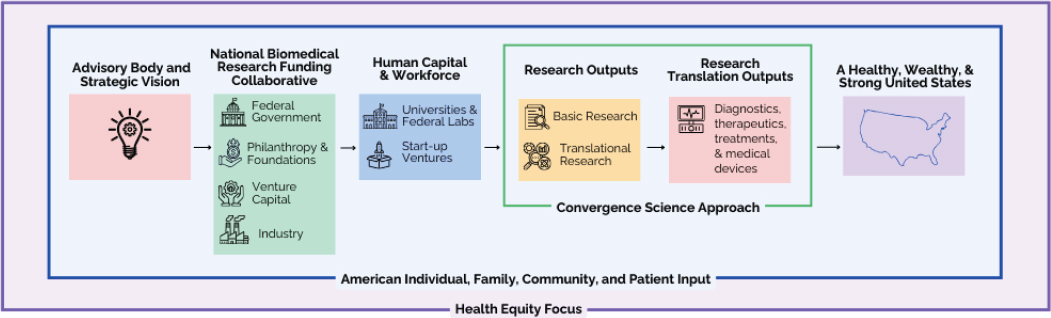

VISION FOR THE U.S. BIOMEDICAL RESEARCH ENTERPRISE OF THE FUTURE

The authors of this Special Publication believe that action is needed in the short and medium terms to revitalize, reinvigorate, and shore up the U.S. biomedical research enterprise. If the actions proposed within this Special Publication are taken, the authors believe that the vision of the U.S. biomedical research enterprise presented below is well within reach (see Figure 1-5).

Vision for the Future

The Pioneer 100 Wellness program, launched by the Institute for Systems Biology, has conclusively shown that leveraging genomic data, emerging technology, and improved understanding of disease mechanisms can improve health—a snapshot of what the future U.S. biomedical research enterprise could be. In 2013, the Institute for Systems Biology team recruited 108 people to have their genomes sequenced and measures of health analyzed for 9 months (Hood and Price, 2023). Participants wore activity trackers to measure their sleep, activity, and heart rate (Hood and Price, 2023). The researchers collected blood, saliva, and stool from each participant to measure and analyze “1,200 blood analytes—proteins, metabolites, and other clinically relevant chemicals,” including cortisol and the number and types of bacteria in their gut microbiomes (Hood and Price, 2023). A wellness and nutrition coach used these measurements to develop individual action plans for each participant and “persuade the pioneers to change their lifestyles in accordance with the individual recommendations”—whether they were at risk for diabetes or another disease, or simply lacking specific nutrients (Hood and Price, 2023).

Of the 108 participants, 53 had prediabetes. By the end of the 9-month intervention period, 38% improved their blood glucose levels, 55% improved their insulin resistance, and 7 individuals had reversed the presence of prediabetes entirely (Hood and Price, 2023). The personalized action plans resulted in a 12% improvement in the presence of inflammation biomarkers that are associated with Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, heart disease, and diabetes; a 6% improvement for markers associated with coronary artery disease; and a 21% improvement for markers associated with improved nutrition (Hood and Price, 2023).

Imagine if every American could have access to individualized action plans such as these to improve their health.

Imagine if every American had enough trust in the U.S. biomedical research enterprise to contribute their genomic, health, and medical data to advance precision medicine and machine learning. This robust data set could reveal opportunities for everyone to enhance their health and provide the ability to predict, prevent, and precisely mitigate disease development. A future health care delivery system would partner with individuals, enabling them to take control of their health by providing specific plans to prevent or mitigate disease. When disease did occur, health care systems would provide therapies designed to treat their exact condition, precisely.

Imagine a health care delivery system focused on enhancing health and longevity while preventing disease instead of waiting until people are sick to treat

them. This approach would not only improve the health of the nation but also potentially save hundreds of billions of dollars and reduce the more than 17% of GDP the United States currently spends on health care (CMS, 2023).

Imagine not only increasing individual life expectancy but also reducing the ill health that typically accompanies aging—including chronic diseases, dementias, frailty, and disability. Unveiling the biology of aging could provide essential knowledge toward delaying aging and its consequences, leading to a better health span for all.

Imagine the 58.5 million Americans who currently live with arthritis, one of the top three causes of work disability, being able to work without pain, saving $164 billion in lost earnings and immeasurably improving their quality of life (Murphy et al., 2018; Theis et al., 2018).

Imagine the 37 million Americans living with diabetes in 2022 earning the $28.3 billion lost because they could not work due to disability, and being able to spend more hours, days, and years with their friends and families (DRIF, 2023; Parker et al., 2023).

Imagine eliminating the health disparities that cause 30% more Black individuals to die from cardiovascular disease than their White peers; American Indian or Alaska Native individuals to develop diabetes at twice the rate of their White peers; and American Indian or Alaska Native, Hispanic, and Black individuals to be more than 1.5 times as likely to die from COVID-19 as their White peers (HHS OMH, n.d.; Hill et al., 2023; Terrie, 2023).

Imagine strategic investments to support improvements in health that will not only save lives and improve quality of life but also bolster individual wealth, eliminate unnecessary costs, and improve the economy. We can achieve this vision if we act now.

This page intentionally left blank.