Practices to Identify and Mitigate PFAS Impacts on Highway Construction Projects and Maintenance Operations (2024)

Chapter: 2 Literature Review

CHAPTER 2

Literature Review

This literature review summarizes background information, current practices, and recent research regarding identifying and mitigating locations of PFAS contamination among DOTs. This information influenced the development of the survey questionnaire and its accompanying presentation of the responses, as described in Chapter 3. The literature reviewed also informed the collection of the case examples described in Chapter 4.

The following topics of information were reviewed:

- Definitions related to PFAS contamination and associated regulations or planned regulations;

- Methodologies for identifying and mitigating PFAS impacts related to highway construction and maintenance operations;

- Written DOT policies and guidance for identifying and mitigating locations of PFAS contamination;

- DOT timing and approaches for PFAS screening, sampling, tracking, and pollutant source assessments;

- DOT management and disposal considerations regarding PFAS-contaminated materials, related liability considerations, and legacy DOT right-of-way acquisitions with PFAS contamination; and

- Identification of current or past construction and maintenance materials that may contain PFAS or be cross-contaminated (e.g., containers with PFAS).

Overview of PFAS

PFAS are a class of anthropogenic chemicals first synthesized in the 1930s and valued for their ability to repel grease, oil, and water (4). However, over the last 30 years, research on the toxicity and persistence of PFAS has focused attention on these chemicals as a major concern for human and ecosystem health (20, 21).

PFAS were first produced at a commercial scale in the 1940s and by the 1950s, various PFAS were mass produced and applied to military, industrial, and everyday household products (4). PFAS are used in fluoropolymer coatings on nonstick cookware, water-repellent clothing, stain-resistant fabric and carpet, and other consumer products that resist grease, water, and oil (3, 6). Notably, PFAS are also found in aqueous film-forming foams (AFFFs, also known as aqueous firefighting foams), which are valuable for extinguishing hydrocarbon (e.g., aircraft fuel) fires at airports and military installations (3).

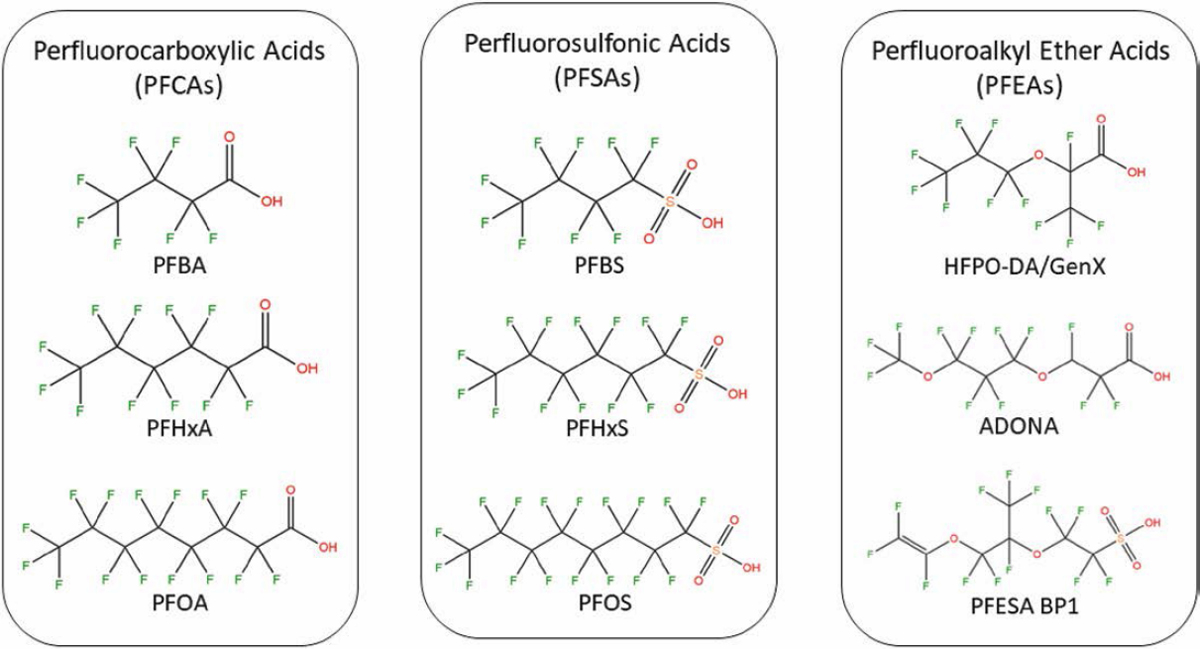

PFAS are defined as “substances that contain one or more C atoms on which all the H substituents present in the nonfluorinated analogues from which they are notionally derived have been replaced by F atoms, in such a manner that they contain the perfluoroalkyl moiety CnF2n+1–” (22, p. 515).

In more common parlance, this means that PFAS are molecules that contain multiple fluorine atoms bonded to carbon. Assorted PFAS structures are presented in Figure 2.1.

Because the carbon–fluorine bond is particularly strong, PFAS do not naturally break down into safer substances and persist in the environment for thousands of years, earning them the nickname “forever chemicals” (6). Their persistence in the environment and affinity for proteins cause PFAS to bioaccumulate in food webs; PFAS can be found in the blood serum of 99% of humans and virtually all animals (5). A study of more than 18,000 people in the United States between 1999 and 2018 found PFOS, PFOA, perfluorohexanesulfonic acid (PFHxS), or perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA) in the blood of all participants (6).

Those PFAS that have been well studied are associated with multiple cancers, cell toxicity and mortality, genotoxicity, changes in body development, and deleterious effects on the circulatory system, endocrine system, immune system, metabolic and digestive system, musculoskeletal system, nervous system and behavior, reproductive system, respiratory system, urinary system, and sensory system (7). However, most members of this large chemical class have not yet been screened for health effects.

Typical Sites of PFAS Contamination

PFAS contamination is found throughout the world, with the highest concentrations often near and around firefighting training facilities, airports, and military installations (23, 24). Since the 1970s, the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) has used AFFFs extensively for extinguishing chemical fires, crash crew training exercises, hangar system operations and testing, and other emergency response actions. The DoD phased out PFOS- and PFOA-containing AFFFs in 2015, but old stock is still in use. The DoD is working with the Strategic Environmental Research and

Development Program and the Environmental Security Technology Certification Program to develop fluorine-free foams to replace AFFFs (24).

PFAS have been used extensively in vapor suppression systems for metal plating industries and are often found in and near metal plating shops (24). PFAS are also concentrated in water sources, wastewater, and agricultural sites near manufacturing plants that apply PFAS (23, 25).

PFAS regularly migrate from the source of their contamination through surface water and groundwater plumes, atmospheric deposition, and the engineered conveyance of affected materials (8, 9). Fire training areas at military sites and airports, PFAS manufacturing sites, metal plating operations, land-applied wastewater biosolids, landfills, and pulp and paper mills are known sources of contamination from which PFAS may migrate (10). Because of their widespread use, persistence, and mobility, PFAS are now ubiquitous in soils and can be detected at low concentrations even in soils distant from any likely source (11). These background concentrations, however, are typically much lower than those near directly affected sites (12).

PFAS manufacturers voluntarily phased out production of PFOA and PFOS for all uses in 2015 and shifted production to structurally similar replacements (26). A common replacement PFAS is hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid (HFPO-DA), sometimes called GenX. This compound belongs to the subclass of perfluoroalkyl ether acids. Other common replacement PFAS are short-chain perfluorocarboxylic acids (PFCAs), such as perfluorobutanoic acid, and short-chain perfluorosulfonic acids (PFSAs), such as perfluorobutanesulfonic acid.

Because of nuances in historical use and complex nomenclature, differentiating legacy PFAS (e.g., PFOS) from novel replacement PFAS (e.g., perfluoroalkyl ether carboxylic acids) is challenging for many engineers and practitioners. Such differentiation can be useful for determining the age and source of PFAS contamination. Likewise, distinguishing PFAS subclasses can provide insights into the probable origins and extent of PFAS contamination. For example, semivolatile fluorotelomer alcohols are easily transported via atmospheric deposition and may be confined to surficial soil and water, whereas subsurface plumes from AFFFs typically have greater concentrations of PFSAs than PFCAs.

Similarly, physicochemical properties influence which PFAS are most likely to be found in environmental compartments of concern to DOTs. For instance, anionic PFAS are more likely to be found in aqueous matrices, such as stormwater and dewatered construction groundwater, whereas cationic and zwitterionic PFAS (e.g., fluorotelomer betaines) are more likely to associate with soils. Therefore, an understanding of matrix effects is essential for properly contextualizing DOT sampling and analyses. DOTs can employ numerous quantification methods—including EPA standard methods—to quantify aggregated (e.g., total oxidizable precursor assay) or targeted (e.g., EPA Draft Method 1633) PFAS concentrations.

Federal Regulations

The EPA has provided guidance for measuring PFAS contamination but thus far has largely left regulation to the states. There are currently no binding federal regulations for PFAS. However, maximum contaminant levels (MCLs) have been proposed for drinking water (Table 2.1) and more rulemaking is under way. The EPA has also issued lifetime health advisory levels for PFAS in drinking water as nonregulatory guidance to protect human health (Table 2.2).

The EPA has begun the process to designate PFOA, PFOS, their chemical precursors, and seven other PFAS as hazardous substances under CERCLA (16), stating that, “This proposed rulemaking would increase transparency around releases of these harmful chemicals and help to hold polluters accountable for cleaning up their contamination” (14). The designation of PFAS as

Table 2.1. EPA-proposed MCLs of PFAS in drinking water (as of March 13, 2023) (13).

| Species | Maximum Contaminant Level (ppt)a |

|---|---|

| PFOA | 4 |

| PFOS | 4 |

| PFNAb | 10 |

| PFHxSb | 9 |

| GenX/HFPO-DAb | 10 |

| PFBSb | 2,000 |

a Parts per trillion

b Regulated as a mixture based on combined concentrations contributing to a hazard index.

Table 2.2. EPA lifetime health advisory levels for PFAS in drinking water (as of June 15, 2022) (27).

| Species | Advisory Level (ppt)a |

|---|---|

| PFOA | 0.004 |

| PFOS | 0.02 |

| GenX/HFPO-DA | 10 |

| PFBS | 2,000 |

a Parts per trillion

hazardous substances would restrict how DOTs could handle and dispose of impacted materials (16). It would also give the EPA authority to direct cleanup and apportion liability among potentially responsible parties, possibly including DOTs with impacted rights-of-way (15). Litigation is common among potentially responsible parties seeking to contest apportionment of site remediation costs.

Additional pending federal regulation that could affect DOTs includes the designation of PFAS as hazardous waste under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act of 1976, which would affect the cleanup of contaminated sites and disposal of contaminated wastes (28). Further, the EPA will revise effluent limitations guidelines for landfill leachates, textile manufacturers, and wastewater treatment plants, which may affect sources of PFAS on DOT construction and maintenance sites, and designate harmful levels of PFOA and PFOS for aquatic life, which may affect their discharge from construction and maintenance sites (28).

State Regulations

Indiana, Louisiana, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, Washington, West Virginia, and Wisconsin have set their own MCLs, regulations, or advisory levels for PFAS in water sources used for consumption and in public water systems.

Selected state MCLs are listed in Table 2.3.

Table 2.3. State MCLs (in ppt)a for PFAS.

| State | All PFAS | PFOA | PFOS | PFHxS | GenX/HFPO-DA | PFBS | PFNA | PFHxA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MA | 20 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| MI | – | 8 | 16 | 51 | 370 | 420 | 6 | 400,000 |

| NH | – | 12 | 15 | 18 | – | – | 11 | – |

| NJ | – | 14 | 13 | – | – | – | 13 | – |

| NY | – | 10 | 10 | – | – | – | – | – |

| NC | – | 2,000 | – | – | 140 | – | – | – |

| OR | – | 30 | 30 | 30 | – | – | 30 | – |

| VT | 20 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| WA | – | 10 | 15 | 65 | – | 345 | 9 | – |

| WI | 70 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

a Parts per trillion

– = not applicable

States that have not set MCLs may use the EPA’s health advisory levels or MCLs as guidance in decision making (29).

Some states have also imposed regulations that ban PFAS in specific products or drinking water regulations that address PFAS for surface water and groundwater (23, 30, 31, 32). Maine has passed nine regulations addressing PFAS MCLs for drinking water, food products, land application of sludge and septage, landfill disposal, landfill leachate, and state-owned facilities; these regulations specify how to test for PFAS in each situation (17).

Testing Procedures

The EPA has developed standard analytical methods for PFAS, including Methods 533 and 537.1, which test for PFAS in water and soil samples, respectively (33, 34). The EPA is currently drafting Method 1633 to standardize testing procedures for PFAS in aqueous, solid, biosolid, and tissue samples (35). Further, Pennsylvania, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Vermont, and West Virginia have developed their own testing procedures and studies. Pennsylvania prioritizes testing at sites that may affect community water systems, such as military bases, fire training schools and sites, airports, landfills, Hazardous Sites Cleanup Act sites, superfund sites, and manufacturing facilities (19). New Hampshire and Oklahoma provide guidance on testing for public and private water systems (36, 37).

Several states are engaged in statewide PFAS monitoring efforts. Tennessee is testing all drinking water sources in the state. If a public water system has a contaminated water source, then the public water system is also tested (38). Vermont’s testing plan is not specifically for PFAS and includes 94 other contaminants of concern in the state’s water systems (39). West Virginia conducted a statewide PFAS sampling project from June 2020 to May 2021 that sampled 26 water sources and 27 schools and day cares (40). Iowa has also extensively tested water supplies around the state, as specified in its PFAS Action Plan (41).

Action Plans

Alaska, Colorado, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Washington, and Wisconsin have statewide action plans specifically for PFAS contamination. The Iowa, Missouri, and Wisconsin plans have been issued by their respective

departments of natural resources (41, 42, 43). The Alaska and Colorado DOTs are the only state DOTs leading their own PFAS action plans (44, 45). The Alaska DOT is evaluating groundwater, surface water, drinking water, and soils at all its past and present airports and DoD sites for PFAS contamination. If a site is found to be contaminated and affecting a water source, then the affected towns will be supplied with an alternate water source. The Alaska DOT is also seeking nonfluorinated AFFF replacements for use at airports (44). Colorado DOT’s plan is similar to Alaska’s plan, focusing on commercial airports (45). The Connecticut, Michigan, and New Hampshire DOTs are members of their respective states’ PFAS response teams (46, 47, 48).

The PFAS action plans of several states directly address biosolids and wastewater treatment; drinking water sources (e.g., groundwater and soil near the water table); sources that impact air quality; landfills or other waste disposal sites; food safety; and airports where firefighting foams containing PFAS (AFFFs) were known to have been used (the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation in 2021, the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection in 2021, and the Michigan PFAS Action Response Team in 2019, among others).

Several states have formed interagency groups to minimize human exposure to PFAS within their state. These groups are developing PFAS management strategies, locating likely contaminated areas, building guidance on sample collection and analysis, developing remediation and removal strategies, and surveying materials and storage practices for products containing PFAS. For example, the Connecticut Interagency PFAS Task Force developed an action plan to address challenges related to PFAS (49). This group consists of 16 organizations and is led by the Connecticut Department of Public Health and Department of Energy and Environmental Protection. Other states have formed similar interagency groups, including Michigan (50), Minnesota (51), Pennsylvania (52), and Wisconsin (53). However, none of the identified state action plans explicitly address the effect of PFAS contamination on state DOT construction and maintenance operations.

With a few state DOTs having their own PFAS action plans, the U.S. DOT has announced that it is producing a new action plan that will use procurement policies to prioritize products free of harmful pollutants, such as PFAS, in an attempt to give state DOTs more guidance (54).

Literature Review Summary

Research is prevalent on PFAS themselves and PFAS in relation to airports, but there is relatively little DOT-focused research on PFAS effects. In 2017, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine published a comprehensive resource document for airport industry practitioners on best practices for management and remediation of PFAS found at airport sites (55). No similar guidance exists addressing PFAS management for state DOTs, and no state DOTs have their own comprehensive guides for identifying or managing PFAS if encountered during construction or maintenance operations outside airport source sites. Nonetheless, the information and resources summarized within this chapter provided the background from which to develop and conduct the synthesis survey discussed in the following chapter.