Progress Toward Restoring the Everglades: The Tenth Biennial Review - 2024 (2024)

Chapter: 2 Restoration Progress

2

Restoration Progress

This committee is charged to discuss restoration accomplishments and assess “the progress toward achieving the natural system restoration goals of the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan [CERP]” (see Chapter 1 for the statement of task and Appendix A for a discussion of restoration goals). In this chapter, the committee updates the National Academies’ previous assessments of CERP and related non-CERP restoration projects (NASEM, 2016, 2018, 2021, 2023; NRC, 2007, 2008, 2010, 2012, 2014). The committee also discusses programmatic and implementation progress and the ecosystem benefits resulting from the progress to date.

PROGRAMMATIC PROGRESS

To assess programmatic progress, the committee reviewed primary issues that influence CERP progress toward its overall goals of ecosystem restoration. These issues, described in the following sections, relate to project authorization, funding, and project scheduling.

Project Authorization

Once project planning is complete, CERP projects with costs exceeding $25 million must be individually authorized by Congress before they can receive federal appropriations. Water Resources Development Acts (WRDAs) have served as the mechanism to congressionally authorize U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

(USACE) projects. In the 20 years since the CERP was launched in WRDA 2000, six WRDA bills have been enacted:

- WRDA 2007 (Public Law 110-114), which authorized Indian River Lagoon (IRL)-South, Picayune Strand Restoration, and the Site 1 Impoundment projects;

- Water Resources Reform and Development Act (WRRDA) 2014 (Public Law 113-121), which authorized four additional projects (C-43 Reservoir, C-111 Spreader Canal [Western], Biscayne Bay Coastal Wetlands [BBCW Phase 1], and Broward County Water Preserve Areas [WPAs]);

- WRDA 2016 (Title I of the Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation Act [WIIN Act]; Public Law 114-322), which includes authorization for the $1.9 billion Central Everglades Planning Project (CEPP);

- WRDA 2018 (Public Law 115-270), which authorized the CEPP post-authorization change that included the 240,000 acre-foot (AF) Everglades Agricultural Area (EAA) Storage Reservoir;

- WRDA 2020 (Public Law 116-260), which authorized the Loxahatchee Watershed Restoration Project and combined the EAA Storage Reservoir and the CEPP into a single project; and

- WRDA 2022 (Public Law 117-263), which included no new CERP project authorizations but included additional authorization for IRL-South and authorized expedited completion of the EAA Reservoir.

Authorized CERP projects are sometimes classified by the WRDA bills in which they were authorized—Generation 1 (WRDA 2007), Generation 2 (WRDA 2014), Generation 3 (WRDA 2016 and 2018), and Generation 4 (WRDA 2020)—with the Melaleuca Eradication Project, which was authorized under programmatic authority, included in Generation 1. The occurrence of WRDAs every 2 years (since 2014) has ensured that the authorization process does not delay CERP restoration progress.

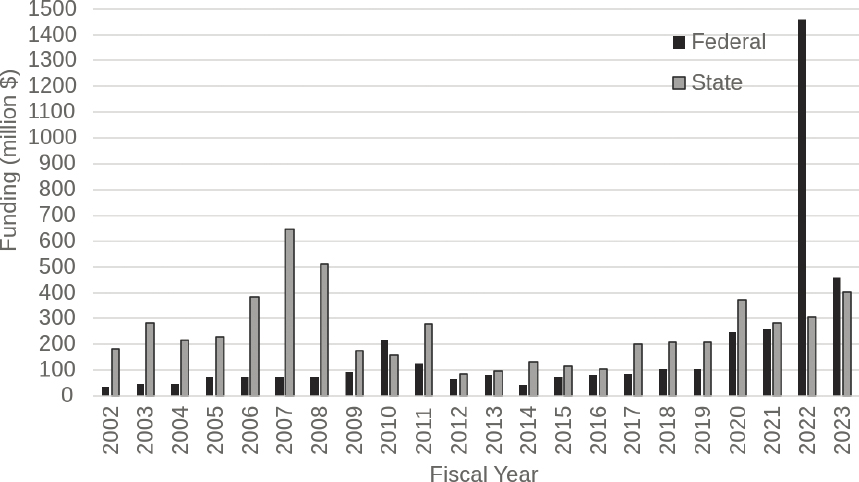

Funding

Within the past 2 years, authorized and requested funding—from fiscal years (FYs) 2023 and 2024, respectively—have continued at record-high levels. In FY 2023, both the state and federal agencies allocated more than $400 million in CERP funding—a first in the history of Everglades restoration (Figure 2-1). These allocations continue the historic pace of funding from FY 2022, when $1.1 billion was appropriated for the Everglades as part of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act in addition to the annual USACE budget. In FY 2024, the USACE has budgeted

SOURCE: Data from SFERTF, 2024.

$413 million for the CERP,1 and the FY 2025 President’s Budget includes a request for $444 million for this program (OMB, 2024). In FY 2024, the State of Florida budgeted $470 million for the CERP (State of Florida, 2023), and the governor has recently signed the budget for FY 2025 with $664 million for the CERP (State of Florida, 2024). Continuation of these record-high budgets will help sustain a rapid pace of project implementation, which will expedite natural system restoration progress.

Through FY 2023 the federal government and the State of Florida have each spent $2.6 billion on CERP planning and construction (USACE, 2023d). Current projections estimate that CERP completion will total $23.2 billion (in FY 2020 dollars; USACE and DOI, 2020), although future project authorizations and modifications may affect that estimated total.

Project Scheduling and Prioritization

The anticipated future progress of CERP projects and the relationships among all the federally funded South Florida ecosystem restoration projects and some

___________________

1 See https://www.usace.army.mil/Missions/Civil-Works/Budget/#Work-Plans.

highly relevant state-funded projects are depicted in the Integrated Delivery Schedule (IDS). The IDS is not an action or decision document but rather a useful communication tool that provides information to decision makers across agencies to guide planning, design, construction sequencing, and budgeting. The schedule is developed by the USACE and the South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD) in consultation with the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI), the South Florida Ecosystem Restoration Task Force, and the many CERP constituencies. The IDS replaced the Master Implementation Sequencing Plan, initially developed for the CERP, as required by the Programmatic Regulations (33 CFR §385.31).

Updated versions of the IDS were released in November 2022 (USACE, 2022a) and November 2023 (USACE, 2023e). The 2023 IDS update provides a forecasted project planning, design, and construction schedule for the next 10 years (through 2034), based on optimal funding scenarios. Essentially, the IDS provides the agency’s vision of the appropriate implementation plan based on project dependencies and construction capacity, assuming that funding is not a constraint. All authorized projects are included in the schedule, but not all components are listed if the design has not been completed (e.g., IRL-South natural storage areas, muck removal, and habitat creation).

The past 2 years of historically large funding levels enabled the program to largely keep pace with the aggressive schedule set forth in the 2022 IDS, with no delays on the completion of Generation 1 projects and some delays in Generation 2 and 3 projects, but an expedited plan for completion of the EAA Reservoir. The 2023 IDS assumes continuation of these historically high funding levels, with estimated project costs of $1.5 to $2.0 billion per year between 2024 and 2027. If funding levels return to pre-2023 levels, the pace of implementation will be substantially slower than that shown in the IDS and will require CERP leadership to decide whether to prioritize the rapid implementation of some projects over others to expedite overall ecosystem benefits or substantially delay the completion of all projects.

NATURAL SYSTEM RESTORATION PROGRESS

In the following sections, the committee focuses on recent information on natural system restoration benefits emerging from the implementation of CERP and major non-CERP projects. The implementation status of CERP projects is shown in Table 2-1, and pending unplanned projects are listed in Table 2-2, including Southern Everglades, the last major CERP planning effort and a critical element of restoration for Everglades National Park and Florida Bay.

TABLE 2-1 CERP Project Implementation Status as of May 2024

| Project or Component Name | Yellow Book (1999) Estimated Completion | IDS 2023 Estimated Completion | Project Implementation Report Status | Authorization Status | Construction Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GENERATION 1 CERP PROJECTS | |||||

| Picayune Strand Restoration (Fig. 2-2, No. 1) | 2005 | 2005 | Submitted to Congress, 2005 | Authorized in WRDA 2007 | Ongoing |

| Site 1 Impoundment (Fig. 2-2, No. 2) | 2007 | Submitted to Congress, 2006 | Authorized in WRDA 2007 | ||

|

– Phase 1 |

Completed | Completed, 2016 | |||

|

– Phase 2 |

Not specified | Requires authorization | Project on hold | ||

| Indian River Lagoon-South (Fig. 2-2, Nos. 3 and 4) | Submitted to Congress, 2004 | Authorized in WRDA 2007 | |||

|

– C-44 Reservoir/STA (Fig. 2-2, No. 3) |

2007 | Completed | Completed, 2021 | ||

|

– C-23/C-24 North and South Reservoirs (Fig. 2-2, No. 4) |

2010 | 2030 | Not begun | ||

|

– C-23/24 STA (Fig. 2-2, No. 4) |

2010 | 2025 | Ongoing | ||

|

– C-25 Reservoir/STA (Fig. 2-2, No. 4) |

2010 | 2028 | Not begun | ||

|

– Natural Lands |

NA | Not specified | Not begun | ||

| Melaleuca Eradication and Other Exotic Plants (Fig. 2-2, No. 5) | 2011 | Completed | Final June 2010 | Prog. Authority WRDA 2000 | Completed 2013, operations ongoing |

| GENERATION 2 CERP PROJECTS | |||||

| C-111 Spreader Canal (Western) Project (Fig. 2-2, No. 6) | 2008 | Final component not specified | Submitted to Congress, 2012 | Authorized in WRRDA 2014 | Mostly completed in 2012; S-198 construction on hold |

| Biscayne Bay Coastal Wetlands (Phase 1) (Fig. 2-2, No. 7) | 2018 | 2025 | Submitted to Congress, 2012 | Authorized in WRRDA 2014 | Ongoing |

| C-43 Basin Storage: West Basin Storage Reservoir (Fig. 2-2, No. 8) | 2012 | 2025 | Submitted to Congress, 2011 | Authorized in WRRDA 2014 | Ongoing |

| Project or Component Name | Yellow Book (1999) Estimated Completion | IDS 2023 Estimated Completion | Project Implementation Report Status | Authorization Status | Construction Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broward County WPAs (Fig. 2-2, No. 9) | Submitted to Congress, 2012 | Authorized in WRRDA 2014 | |||

|

– C-9 Impoundment |

2007 | 2034 | Not begun | ||

|

– C-11 Impoundment |

2008 | 2031 | Ongoing | ||

|

– WCA-3A & -3B Levee Seepage Management |

2008 | 2031 | Not begun | ||

| GENERATION 3 CERP PROJECTS | |||||

| Central Everglades Planning Project (CEPP) North (Fig. 2-2, No. 10) | NA | 2030 | Submitted to Congress, 2015 | Authorized in WRDA 2016 | Ongoing |

| CEPP South (Fig. 2-2, No. 11) | NA | 2031 | Ongoing | ||

| CEPP New Water (Fig. 2-2, No. 13) | NA | 2024 | Completed 2024 | ||

| CEPP EAA (Fig. 2-2, No. 12) | NA | Submitted to Congress, 2018 | Authorized in WRDA 2018, 2020 | Ongoing | |

|

– EAA Reservoir and Pump Station |

2030 | ||||

|

– EAA A-2 STA |

2023 | ||||

| GENERATION 4 CERP PROJECTS | |||||

| Loxahatchee River Watershed (Fig. 2-2, No. 14) | 2013 | 2032 | Submitted to Congress, 2020 | Authorized in WRDA 2020 | Not begun |

| CERP PROJECTS IN PLANNING | |||||

| Lake Okeechobee Watershed (Fig. 2-2, No. 15) | 2009–2020 | NA | Third revised draft, Jun. 2022 | Requires authorization | NA |

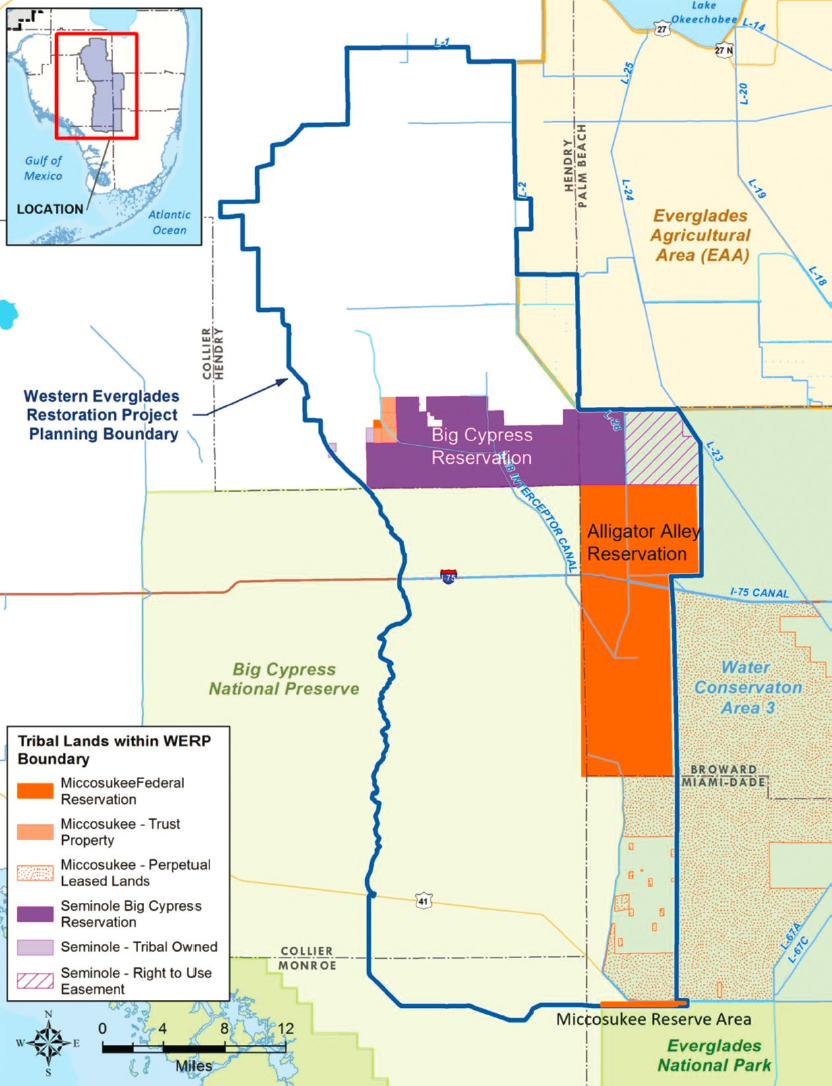

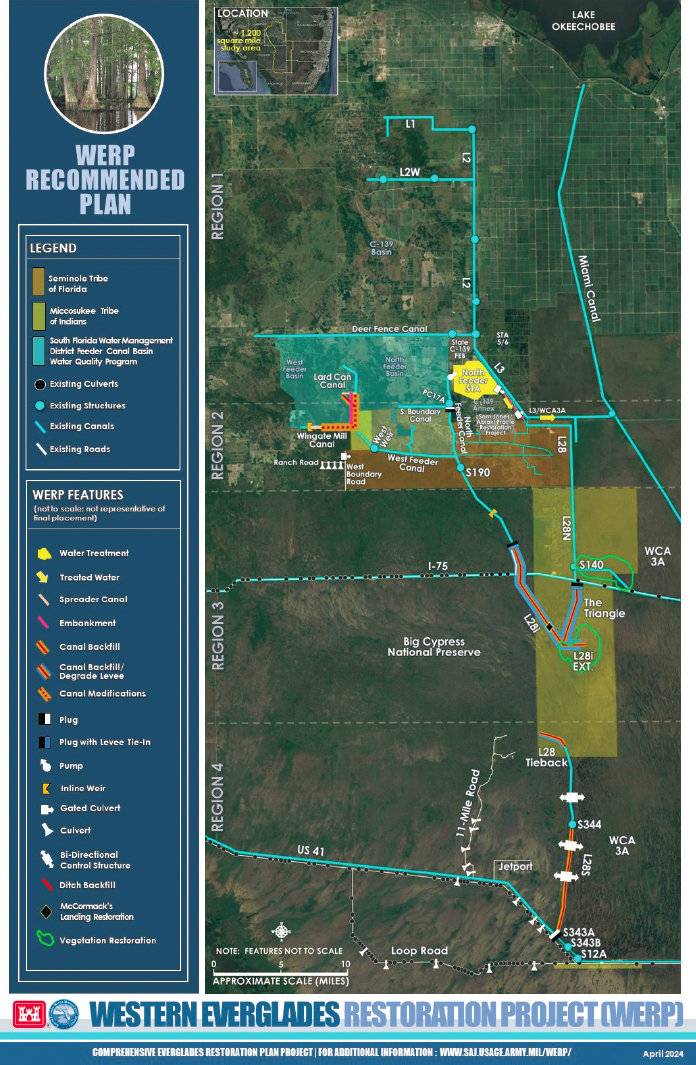

| Western Everglades (Fig. 2-2, No.16) | 2008–2016 | NA | Draft Dec. 2023 | Expected 2024 | NA |

| Biscayne Bay and Southeastern Everglades Ecosystem (Fig. 2-2, No.17) | 2008–2020 | NA | In development | Expected 2026 | NA |

NOTES: Does not include non-CERP foundation projects. NA = not applicable.

SOURCES: Data from NASEM, 2023; Parrott, 2024; USACE, 2023e; Velez, 2024; G. Ralph, USACE, personal communication, 2024.

TABLE 2-2 CERP Projects or Components That Have Not Been Addressed in Prior or Ongoing CERP Planning Initiatives as of June 2024

| Project or Component Name | Estimated Financial Requirement | Status |

|---|---|---|

| PENDING CERP PLANNING EFFORTS | ||

| Southern Everglades: Per USACE and DOI (2020) includes | Not available until project planning completed | Planning process anticipated 2025–2028 |

|

– WCA-3 Decompartmentalization (QQ) |

||

|

– Dade Broward Levee/Pensuco Wetlands (BB) |

||

|

– Broward Co. Secondary Canal System (CC) |

||

|

– Flows to eastern Water Conservation Area (EEE) |

||

|

– Lake Okeechobee ASR (GG) |

||

|

– Central Lake Belt Storage Area (S) |

||

|

– Bird Drive Recharge Basin (U) |

||

|

– Divert WCA-2 Flows to Central Lake Belt Storage (YY) |

||

|

– Divert WCA-3 Flows to Central Lake Belt Storage (ZZ) |

||

| PENDING MAJOR UNPLANNED CERP COMPONENTS | ||

| C-43 Basin ASR (D Phase 2) | $483,000,000 | Not yet begun |

| L-8 Basin ASR (K Part 2) and C-51 Regional Groundwater ASR (LL) | $387,000,000 | On hold |

| Site 1 Impoundment ASR (M Phase 2) | $234,000,000 | Inactive after Hillsboro ASR Pilot |

| Palm Beach Agricultural Reserve Reservoir and ASR (VV) | $211,000,000 | Not yet begun |

| Caloosahatchee Backpumping with Stormwater Treatment (DDD) | $136,000,000 | Not yet begun |

| Southern CREW (OPE) | $28,700,000 | On hold |

| Florida Keys Tidal Restoration (OPE) | $23,100,000 | Suspended |

| Loxahatchee National Wildlife Refuge Internal Canal Structures (KK) | $17,600,000 | On hold |

| Henderson Creek – Belle Meade Restoration (OPE) | $10,800,000 | On hold |

| Comprehensive Integrated Water Quality Plan (CIWQP) | $8,300,000 | On hold |

| Florida Bay Florida Keys Feasibility Study (FBFKFS) | $6,500,000 | Suspended in 2007. The project is planned for the future |

NOTES: Remaining unplanned CERP projects include all projects more than $5 million (2019 dollars) as reported in USACE and DOI (2020), for which the components have not been incorporated in other planning efforts or formally removed from the CERP. Letters in parentheses represent project component code from Yellow Book. Estimated financial requirement derived from SFERTF (2023).

SOURCES: Data from SFERTF, 2023; USACE, 2023e; USACE and DOI, 2020.

The discussions of restoration progress that follow are organized into four major sections based on implementation status.

-

Operating CERP projects (or project increments)

- Picayune Strand Restoration Project

- Melaleuca Eradication

- CEPP New Water

- C-111 Spreader Canal

- BBCW

-

Regional operations plans

- Kissimmee Headwaters Revitalization Schedule

- Lake Okeechobee System Operating Manual (LOSOM)

- Combined Operational Plan (COP)

-

Authorized CERP projects/components not yet operating (or constructed)

- CEPP South, CEPP North, and the EAA Reservoir

- C-43

- IRL-South

- Loxahatchee River Watershed

- C-11 Impoundment

-

CERP projects in planning

- Western Everglades Restoration Project (WERP)

- Lake Okeechobee Watershed Restoration Project (LOWRP)

- Biscayne Bay and Southeastern Everglades Ecosystem Restoration (BBSEER)

The committee’s previous report (NASEM, 2023) contains additional descriptions of the projects and progress through mid-2022. The South Florida Environmental Report (SFWMD, 2024a) and the 2023 Integrated Financial Plan (SFERTF, 2023) also provide detailed information about implementation and restoration progress.

CERP Projects with Recent Information on Restoration Benefits Delivered

The committee’s review in this section is based on reported monitoring data to date for CERP projects for which construction has begun, with emphasis on progress and new information gained during the past 2 years.

Picayune Strand Restoration Project

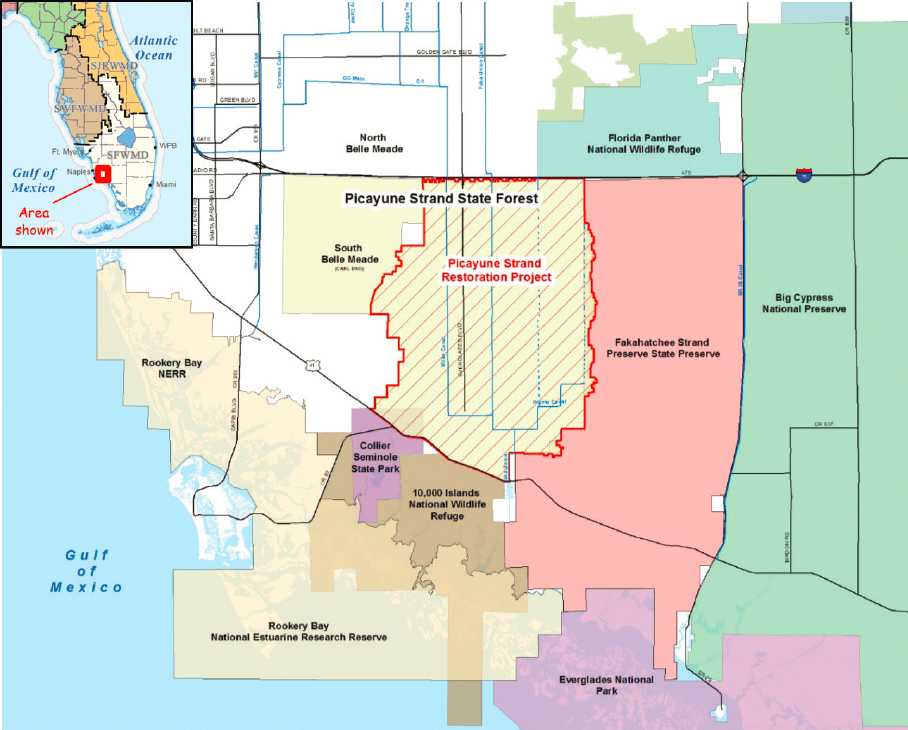

The Picayune Strand Restoration Project (Figure 2-2, No. 1) was the first CERP project under construction. The 55,000 acre (86 mi2) Picayune Strand area in southwest Florida was drained for an intended real estate development,

SOURCE: Map by International Mapping.

Golden Gate Estates-South, which was abandoned before completion. Construction of drainage canals and an extensive road network drained a large area of wetlands, reduced sheet flow to the south into the Ten Thousand Islands National Wildlife Refuge, and altered regional groundwater flow into surrounding areas (Figure 2-3). Restoring the predrainage hydrology should bring multiple

NOTE: Restoration of water levels within the project footprint will enhance the hydrologic conditions in these surrounding natural areas.

SOURCE: Chuirazzi et al., 2018.

ecological and environmental benefits, including an increase in the spatial extent of wetlands, decreased frequency and intensity of forest fires, and increased habitat for endangered species such as the wood stork and Florida panther. The project is also expected to improve groundwater recharge to the City of Naples’ eastern Golden Gate well field, as well as coastal estuarine salinities affected by freshwater point discharges from the Faka Union Canal (RECOVER, 2019).

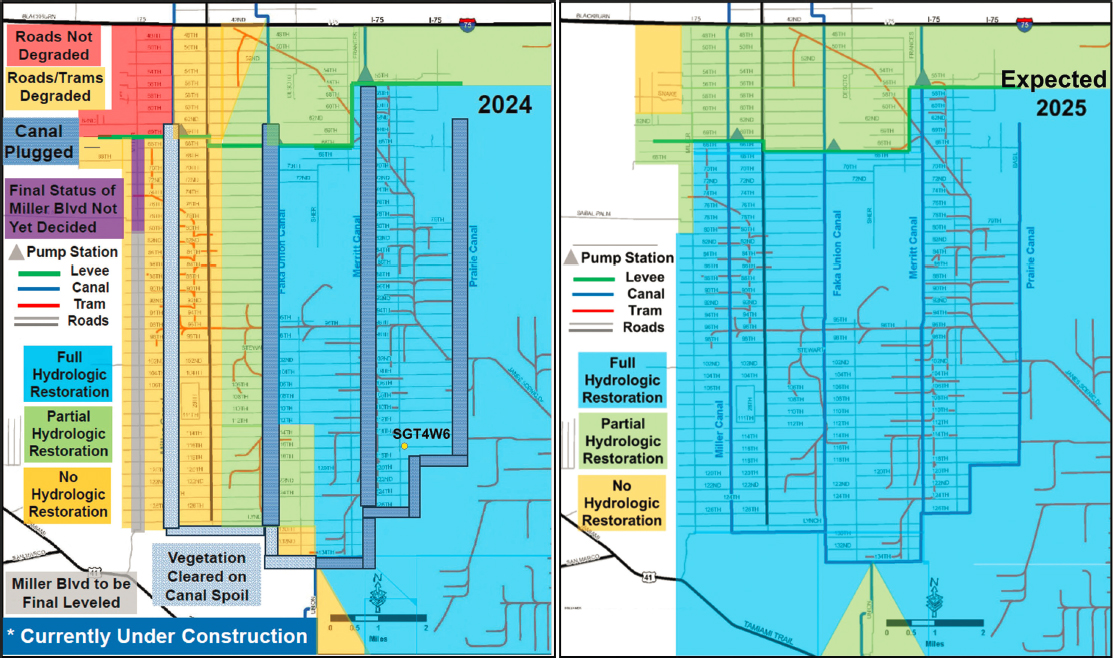

Project components include plugging drainage canals, degrading roads, and removing logging trams (Figure 2-4; USACE and SFWMD, 2004). Construction has

SOURCE: M. Duever, consultant to the SFWMD, personal communication, 2024.

occurred in stages starting with the easternmost portion of the area and proceeding west (Figure 2-5, Table 2-3). The Eastern Stair-step canal was plugged in summer 2021, and 8.4 miles of the Faka Union Canal were plugged by May 2024. The Miller Canal, the westernmost canal, is scheduled to be plugged in late 2024 and 2025 after completion of the Southwest Protection Feature, a levee on the southwest edge of the project intended to reduce flood risk to the agricultural lands to the west of the project. Because of the staged plugging of drainage canals, the degree of hydrologic restoration varies both spatially and temporally. Prior to the 2019–2021 construction, only the northeast corner was considered to have full hydrologic restoration; as of May 2024, roughly half of the project footprint is considered to have full hydrologic restoration, with considerable additional hydrologic restoration expected by the end of 2025 (Figure 2-5).

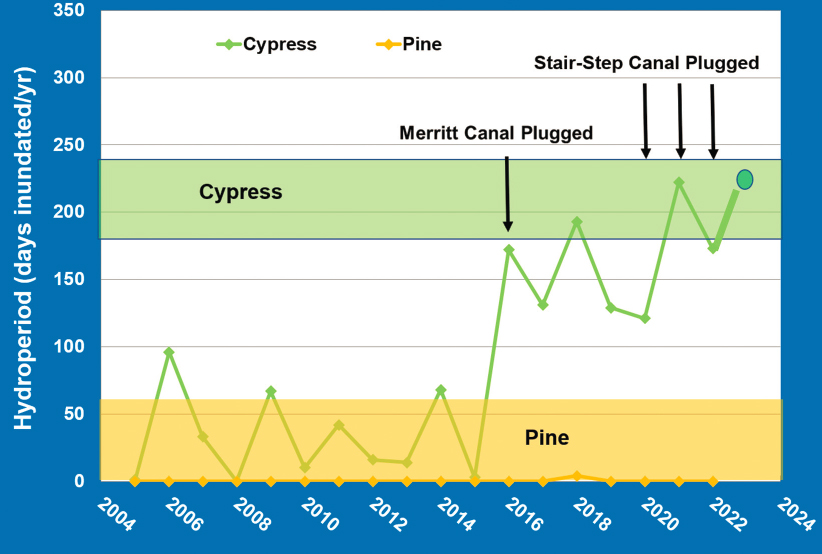

Recent data on natural system restoration progress.

NASEM (2018, 2023) provided a comprehensive review of the hydrologic and vegetation monitoring program. Ongoing groundwater monitoring since release of the committee’s last report suggests that the area south of the Merritt Pump Station continues to show natural hydrological patterns, with target hydroperiods attained for cypress habitat (Figure 2-6). No additional vegetation data are being collected until 2025, with analysis expected in 2026. Thus, the remainder of this section focuses on information obtained during the past 2 years on invertebrate and vertebrate survey data in relation to hydrologic and vegetation outcomes from restoration efforts.

SOURCE: M. Duever, consultant to the SFWMD, personal communication, 2024.

TABLE 2-3 Phases and Progress of the Picayune Strand Project

| Component | Lead Agency | Road Removal (mi) | Logging Tram Removal | Canals to Be Plugged (mi) | Description | Project Phase Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tamiami Trail Culverts | State | NA | NA | NA | 17 culverts constructed | Completed in 2007 |

| Prairie Canal Phase | State (expedited) | 64 | 30 | 7 | Hydrologic restoration of 11,000 acres in Picayune Strand and 9,000 acres in Fakahatchee Strand State Preserve Park | Plugging and road removal completed in 2007; logging trams removed in 2012 |

| Merritt Canal Phase | Federal | 65 | 16 | 8.5 | Merritt pump station, spreader basin, and tie-back levee constructed | Completed in 2015; pump station transferred to the SFWMD in 2016 |

| Faka Union Canal Phase | Federal | 81 | 11 | 8.4 | Faka Union pump station, spreader basin, and tie-back levee constructed | Pump station completed in 2017; 8.4 miles canal plugging completed by May 2024 |

| Miller Canal Phase | Federal/State | 77 | 11 | 13 | Construct pump station, spreader basin, tie-back levee, and private lands drainage canal; remove Western Stair-step canals | Miller pump station completed June 2019. Partial road removal completed September 2022; canal plugging to be completed 2025 |

| Manatee Mitigation Feature | State | 0 | 0 | 0 | Construct warm water refugium to mitigate habitat loss | Completed in 2016 |

| Southwestern Protection Feature | Federal | 0 | 0 | 0 | Construct 7-mile levee, canal, and water control structures for flood protection of adjacent lands | Construction completion estimated in 2024 |

| Eastern Stair-step Canals | Federal | 0 | 0 | 5.2 | Plugging completed in June 2021 |

SOURCES: NASEM, 2023; data updates from M. Duever, consultant to the SFWMD, personal communication, 2024.

SOURCE: Duever, 2023.

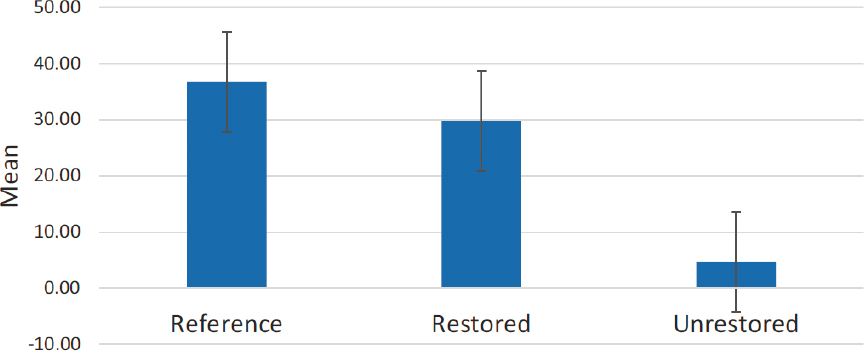

There is some early evidence that animal communities are responding to the changes in hydrology and vegetation enabled by restoration. In comparison to baseline data on the relative abundance and species diversity of aquatic macroinvertebrates collected in 2005–2007 (Bartoszek et al., 2007; Ceilley, 2008), macroinvertebrate assemblages by 2019 in some of Picayune Strand’s cypress habitats had started to exhibit shifts toward the species composition found in reference wetland communities. These shifts included an increase in species richness and recolonization of sites by longer hydroperiod (wetter) indicator species such as freshwater sponges, limpets, and crayfish (Ceilley et al., 2020). Additional monitoring in 2021–2022 revealed similar patterns, including evidence of further convergence of restored sites toward reference conditions since the 2019 macroinvertebrate sampling (Figures 2-7 and 2-8; Ceilley, 2022; Gaglia, 2022). Data on how fish and anuran (frogs and toads) communities are responding to restoration activities in Picayune Strand are limited compared to data on macroinvertebrates but yield important insights for future monitoring of

NOTE: Directional arrows show that restored sites are moving in ordination space toward reference habitats.

SOURCE: Gaglia, 2022.

these taxonomic groups. As of 2019, the spatial extent of successful sampling remained constrained by short hydroperiod conditions not conducive to supporting fish. Moreover, Ceilley et al. (2020) reported abundant capture of the African jewelfish, a nonnative, invasive species, which may complicate the ability to track native fish community recovery. Anuran diversity and abundance surveys have thus far been limited to monitoring of artificial structures (i.e., PVC pipes that treefrogs use for shelter). The results have primarily yielded invasive treefrogs to date; more than 90 percent of frogs sampled from 2005 to 2019 in Picayune Strand have been Cuban treefrogs (Ceilley et al., 2020; Clark, 2020), obfuscating the ability to discern how native species are responding to restoration. Although this sampling technique has benefits such as ease of standardized, repeated sampling over time, it has several limitations. For example, only refuge-seeking species such as treefrogs typically utilize these artificial habitats, leaving the presence of other species (e.g., Ranid frogs) in the anuran community unknown. Adopting the use of automated audio recording technology (e.g., “frog loggers”;

SOURCE: Gaglia, 2022.

De Solla et al., 2006; Dorcas et al., 2009; Measey et al., 2017; Stevens et al., 2002), with the possibility of employing artificial intelligence to support analyses of recordings (Gan et al., 2021; Lapp et al., 2021), would provide a more comprehensive assessment of the species of amphibians using restored habitats and might help to overcome possible sampling biases toward a single invasive species. Automated audio recordings offer the additional benefit of documenting broader changes to the soundscape in response to restoration activities. For example, ecoacoustics are increasingly used to document bird diversity and even underwater fauna (Desjonquères et al., 2020), as well as responses of ecosystems to restoration (Ramesh et al., 2023) and the invasion of nonnative species (Barney et al., 2024; Hopkins et al., 2022; Ribeiro et al., 2022).

The committee’s overall conclusion is that restoration of hydrology in the Picayune Strand Restoration Project appears to already be generating benefits to the local flora and fauna, with vegetation and macroinvertebrate communities responding favorably. Additional longitudinal monitoring will be needed to continue documentation of recovery, especially given the magnitude of seasonal and inter-annual variation. Sampling methods for some species (e.g., amphibians) need to evolve to generate a clearer picture of what species are responding to restored hydrology. Modern passive acoustics are one example of a sampling

method that could have far-reaching benefits for Everglades restoration. Invasive species will remain a challenge, and their management will be key to the reestablishment of some native species.

Recent issues affecting progress.

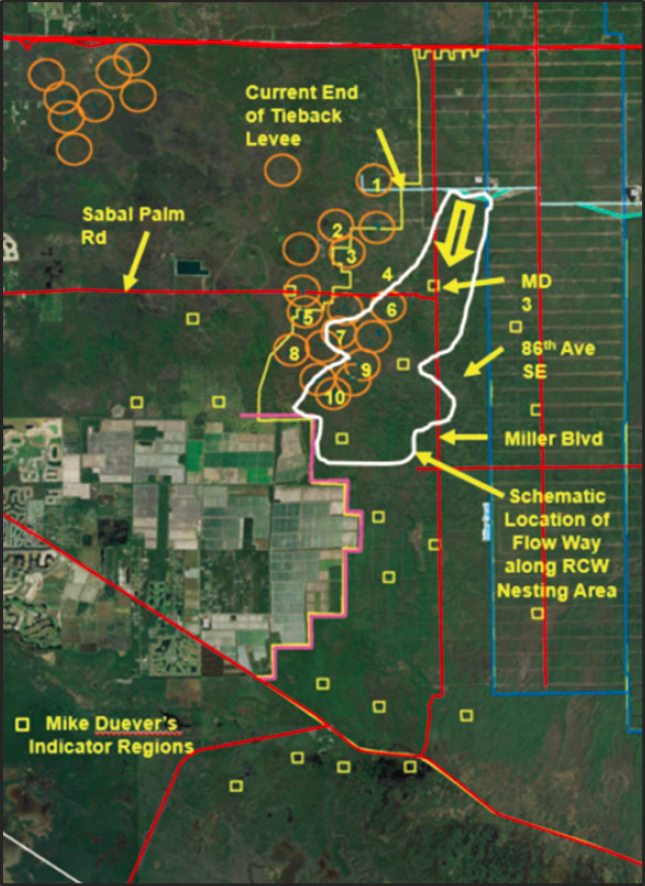

Newly discovered, unanticipated impacts of the project on endangered red-cockaded woodpeckers (RCWs, Dryobates borealis) will likely require design modifications in the vicinity of the Miller Canal. To date, impacts on RCWs have not been an important consideration because the species does not occur in the original project area. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) Biological Opinion included in the Project Implementation Report (PIR) (USACE and SFWMD, 2004) thus focused on how the project would impact the species’ potential habitats—mesic and hydric pine flatwoods—in the project footprint and concluded that the project would not adversely affect the species. However, new analyses completed in early 2024 have revealed that the project will likely harm RCW habitat in the adjacent South Belle Meade tract to the west of the original project area (Figure 2-9).

Adverse impacts of the project on RCWs in Belle Meade were not totally unanticipated, because analyses included in the PIR estimated that the project would result in a roughly 14 percent loss each of mesic and hydric pine flatwoods in Belle Meade (USACE and SFWMD, 2004). At the time, the RCW population in Belle Meade was very small, having been extirpated in 2000 and reestablished in 2001. In 2004, it consisted of only four family groups (Folk, 2018). Therefore, there was little concern about the impact of the project on the Belle Meade RCWs, but the population continued to expand, reaching a stable population size of 14–15 family groups by 2016 (Folk, 2018; Mangione and Spickler, 2022). Potential impacts on the RCW population became an issue in 2019 when new modeling associated with National Environmental Policy Act analysis for the Southwest Protection Feature redesign indicated that the project would create a hydrologic flow-way running from the Miller pump station through the southeastern portion of South Belle Meade (Figure 2-9). The resulting increase in hydroperiod was projected to convert a significant portion of the pine habitat currently occupied by RCWs to wet prairie and marsh that is unsuitable for RCWs.

The situation is complicated by the fact that unlike the original project area, in which development of the failed Golden Gates Estates-South left the landscape in need of restored hydrology, no such need exists in South Belle Meade, which is part of Picayune Strand State Forest. Although RCW habitat in Belle Meade has suffered from wildfires and a hurricane in recent years, hydrologically it is otherwise in good condition (J. Spickler, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, and M. White, Florida Forest Service, personal communication, 2024). Hence, the Picayune Strand Restoration Project does not appear to provide any benefits to RCWs in South Belle Meade that could compensate for identified negative effects.

SOURCE: USACE et al., 2023b.

In response to the projected adverse impacts on RCW habitat, the Project Delivery Team is proposing to leave a section of Miller Boulevard from 64th Avenue to 80th Avenue to act as a berm. This option does not require new features or significantly increase costs, nor is its implementation likely to delay construction (A. McKenzie, SFWMD, personal communication, 2024). Whether resolving this issue delays completion of the final stage of construction of the Picayune Strand Restoration Project instead depends on the length of time it takes to move the selected option through the approval process. This issue is discussed further in Chapter 5 in the context of adaptive management.

Melaleuca Eradication and Other Exotic Plants

CERP funds were used to construct the Biological Control Rearing Annex, adjacent to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Invasive Plant Research Laboratory (IPRL) in Davie, Florida, and CERP operational funding ($660,000 per year) supports biocontrol efforts for invasive plants in the Everglades (A. Dray, USDA, personal communication, 2024). The IPRL evaluates potential insect or fungal natural enemies in the native range of an invasive plant, obtains permits to export and import those species, raises them in quarantined conditions, evaluates how best to produce large numbers and release them to the wild, obtains permits for those releases, and then monitors the success of the releases. In general, biological control measures complement physical control measures (e.g., cutting or herbicide application) (Dray et al., 2023).

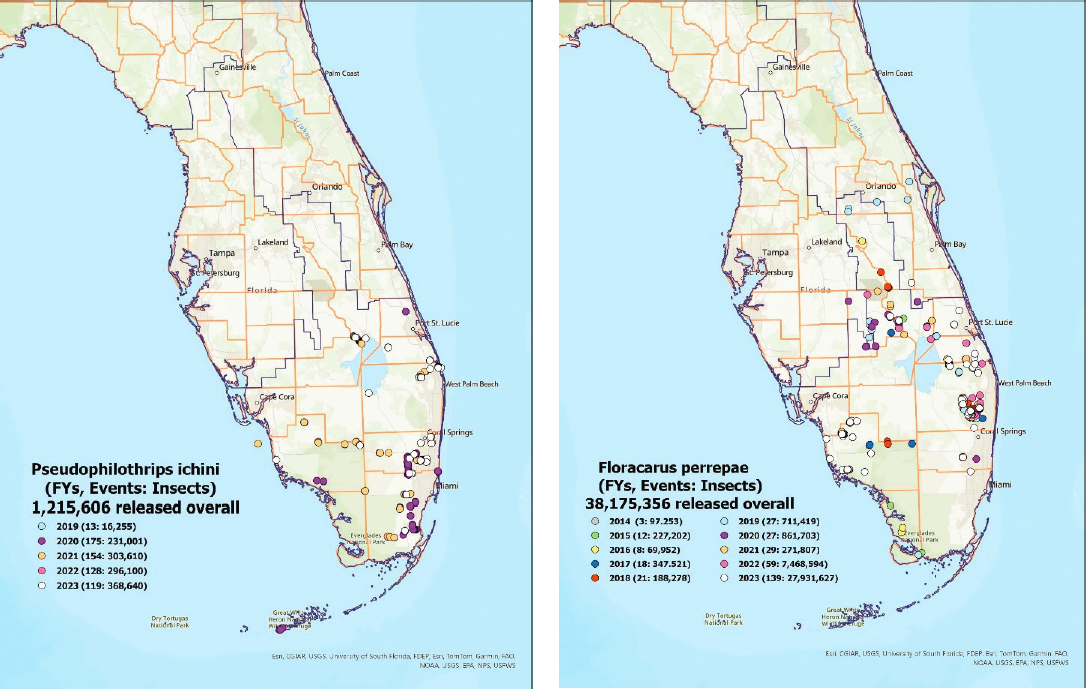

Five particularly problematic invasive plants that are the focus of recent and ongoing management and biocontrol in the South Florida ecosystem are listed in Table 2-4. Figure 2-10 shows recent information on the locations, numbers of release events, and numbers of released insects for two major biocontrol species. Melaleuca was once the most vigorously managed invasive plant, but integrated control measures, including biocontrol by a weevil, a sap-sucking psyllid, and a midge, have reduced the area dominated by Melaleuca by approximately 75 percent (Smith, 2022). In South Florida, Melaleuca control is considered to be in maintenance mode and is no longer targeted by active control methods except in areas where other invasive species are being controlled. The biological control agents drastically reduce establishment of seedlings except in persistently wet areas where the weevil—the most effective biocontrol agent—does not pupate (Smith, 2022). IPRL identified another midge species from the Melaleuca native range, the tip-galling midge, Lophodiplosis indentata, that was able to complete its life cycle in wet areas. Lophodiplosis indentata was granted a release permit in April 2022 and was introduced at one site in June 2023. A monitoring grid has been set up to confirm establishment of a field population and detect spread from the release site (Dray et al., 2023).

TABLE 2-4 Biocontrol Agent Rearing for Invasive Plant Species Control from 2019 to 2024

| Invasive Species | Biocontrol Agents in Use |

|---|---|

| Melaleuca (Melaleuca quinquenervia) | tip-galling midge (Lophodiplosis indentata; in testing) |

| Brazilian pepper (Schinus terebinthifolia) | Brazilian peppertree thrips (Pseudophilothrips ichini) |

| water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) | water hyacinth planthopper (Megamelus scutellaris) has been used but is no longer needed to maintain control |

| Old World Climbing Fern (Lygodium microphyllum) | Lygodium mite (Floracarus perrepae) Lygodium defoliator moth (Neomusotima conspurcatalis) |

| air potato (Dioscorea bulbifera) | air potato beetle (Lileoceris cheni) has been used but is no longer needed because control has been reached |

SOURCE: Data from Dray et al., 2022.

Brazilian pepper is one of the most invasive upland shrubs in Florida and is problematic elsewhere. It has been primarily controlled by chemical and mechanical means, but biocontrol is now provided by two insect species. The Brazilian pepper thrips, Pseudophilothrips ichini, was first released in July 2019 and is currently being mass reared and distributed. Monitoring has demonstrated that it has established persistent populations in the field and is spreading into new areas (Dray et al., 2023). A second species, a leaf galler (Calophya latiforceps), was approved for release in 2019 but as of 2022 has not been released because the rearing colony at IPRL was lost during the pandemic and has not yet been replaced by collecting new insects in Brazil (Cuda et al., 2023).

Water hyacinth is an extremely invasive aquatic nuisance. Control efforts using herbicides started in the 1940s. Frequent repeated herbicide sprays are required because water hyacinth rapidly regrows after being sprayed. Biocontrol was started in the 1970s in an attempt to provide more sustainable biological control (Goode et al., 2021). The three biocontrol insect species introduced in the 1970s effectively reduced biomass of water hyacinth but did not substantially reduce cover (Tipping et al., 2014), and immature stages were killed by herbicide use. Since 2007, IPRL has used CERP funding to identify biocontrol species that are less effected by herbicide use. The water hyacinth planthopper, Megamelus scutellaris, was released starting in 2010. In experimental conditions, the combination of biocontrol and herbicide use reduces water hyacinth biomass to zero or near-zero and reduces regrowth, which increases the time between required herbicide sprays (Tipping et al., 2017). Megamelus scutellaris is less effective in the field because dispersal of the planthopper makes it difficult to maintain high densities on water hyacinth plants.

The Old World Climbing Fern is one of the worst invasive plants in moist areas of central and southern Florida. First reported as naturalized in 1965, it spreads horizontally and vertically to form thick mats covering other vegetation.

SOURCE: Dray et al., 2023.

It is a difficult plant to control because it is widespread, it covers large areas, and herbicide use is expensive. Two species, brown lygodium moth, Neomusotima conspurcatalis, and the lygodium mite, Floracarus perrepae, were released in 2008, but in the field, neither has a consistent effect on Lygodium spread (Walker et al., 2024). The brown lygodium moth is no longer being reared and released because of disease issues and labor-intensive maintenance (Dray et al., 2023). IPRL is evaluating the suitability of additional natural enemies as biocontrol agents (Walker et al., 2024).

The air potato vine is invasive across the southeastern United States. Like the Old World Climbing Fern, it spreads horizontally and vertically and covers extant vegetation. Large-scale field releases of a beetle, Lilioceris cheni, started in 2012 (Rayamajhi et al., 2019) and continued until 2019. Field monitoring shows that greater than 90 percent of air potato vines are damaged by L. cheni and vegetative reproduction is greatly reduced, to the extent that additional releases and herbicidal measures are not needed. The plant is no longer considered a priority invasive species by land managers (Overholt et al., 2016; Rayamajhi et al., 2019). Rearing and release of L. cheni was terminated in 2022 (Dray et al., 2021).

Evaluating the success of biocontrol measures is complicated because biocontrol has the potential to impact large areas but usually has a chronic, not an acute, effect that acts over long time frames. Current species-specific monitoring has focused on assessing population persistence in and dispersal from introduction sites (Dray et al., 2022). There are examples of substantial impact in limited areas (Figure 2-11), but landscape-scale effects are more difficult to monitor. In general, biocontrol has generally been viewed as a success for Melaleuca and air potato vine but has been less effective for other species for various reasons.

Vegetation mapping using remote sensing is the best way to assess large-scale effects of invasive species management, using trained staff to identify species-specific signatures in remote-sensed imagery. The recently completed vegetation map of Everglades National Park, using color-infrared aerial photography taken in 2009 (Ruiz et al., 2021), includes maps of locations and cover of Brazilian pepper, Melaleuca, and Lygodium, although Lygodium was difficult to detect. Because these maps are based on aerial photography, they only show areas where an invasive species is apparent in the canopy, but they provide a baseline landscape-scale assessment. An updated vegetation map based on more recent imagery would provide a useful means to assess large-scale progress in the control of invasive plants in the Everglades.

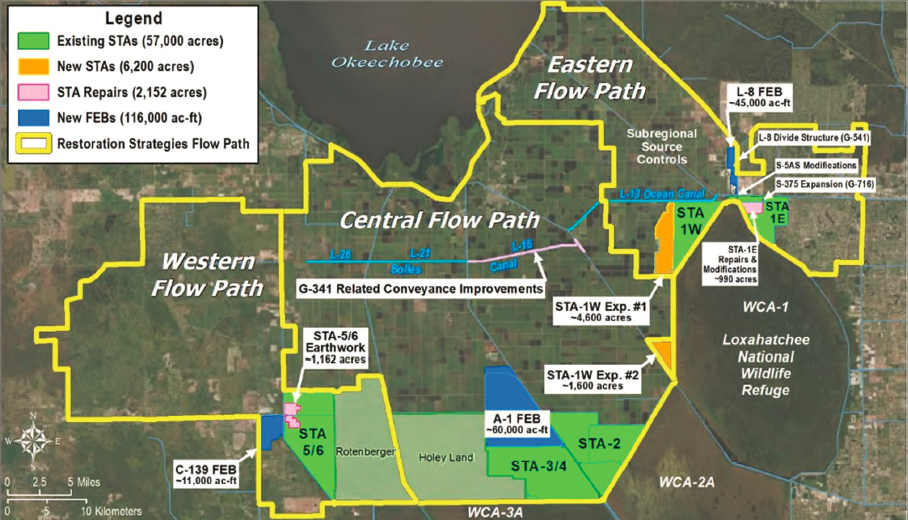

Central Everglades Planning Project

The CEPP is the keystone project in the restoration of the central heart of the Everglades. It will provide the means to send additional water south through

NOTE: The helicopter shadow helps delineate the extent of the damage.

SOURCE: Dray et al., 2022.

the Water Conservation Areas (WCAs) and Everglades National Park to Florida Bay, reduce harmful discharges to the northern estuaries, and improve the timing and distribution of flow in the central Everglades (USACE, 2024a). The CEPP continues to progress at the rapid pace that has characterized it throughout its development, authorization, and implementation (NRC, 2014). The CEPP is a complex project with four phases, each with multiple components: CEPP South, CEPP North, CEPP New Water, and CEPP EAA. Its many parts include improvements in seepage management; improvements in conveyance through filling of canals, levee removal, and addition of new structures such as pump stations and

gated spillways; a large water storage feature (the EAA Reservoir); and construction of the A-2 stormwater treatment area (STA) to ensure that the new inflows comply with existing water quality requirements (Figure 2-12). Although all of these project components are under active construction, in this section the committee discusses CEPP New Water, which is now operating with evidence of restoration benefits. The other CEPP project components are discussed in a later section under projects under construction.

CEPP New Water.

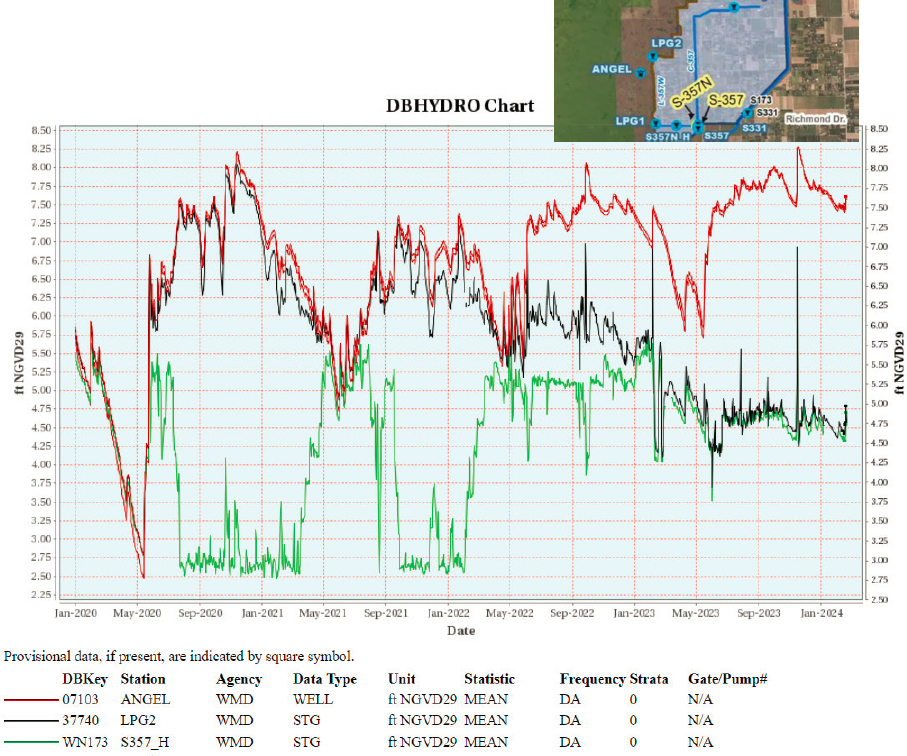

CEPP New Water consists of a single project—a partial depth seepage barrier. Its objective is to reduce seepage from Northeast Shark River Slough into the 8.5 Square Mile Area to the east (Figure 2-13), reducing flood control constraints on operations to allow more existing water to flow south. Previously, the Limestone Products Association constructed 5 miles of seepage barrier (35 feet deep) south of Tamiami Trail along the L-31N levee (also known as the L-31N Rock Miners Seepage Wall) to the north of the CEPP New Water project, and in December 2022 the SFWMD completed construction of a 2.3-mile, 63-foot-deep seepage barrier adjacent to the 8.5 Square Mile Area immediately south of the project (Figure 2-13). CEPP New Water created an additional 5.0 miles of seepage barrier (55–65 feet deep) running from the SFWMD seepage barrier north to the L-31N Canal. There will be a 1.6-mile gap between this new seepage barrier and the existing Rock Miners Seepage Wall to the north (Figure 2-13). CEPP New Water was completed in early 2024 (Parrott, 2024).

It is already evident that the two new seepage barriers will greatly reduce, and perhaps even eliminate, flood control constraints imposed by the 8.5 Square Mile Area/Las Palmas community within the CEPP footprint. Prior to the COP, these constraints for decades completely stymied every attempt to restore the historic distribution of flow between Northeast and Western Shark River Slough (NASEM, 2021). Although the COP has been highly successful in restoring historic flow patterns, it has not been immune to these constraints, experiencing four events in which flood control constraints affected operations in water year (WY) 2021 and two more in WY 2022 (NASEM, 2023). With the completion of the SFWMD seepage barrier and the CEPP New Water curtain wall, there have been no such events since (see also The Combined Operational Plan below) (B. Mills, SFWMD, personal communication, 2024). The change in hydrology can be seen in Figure 2-14, which shows that water levels within the 8.5 Square Mile Area now remain up to 3 feet lower than water levels in the adjacent slough. The importance of eliminating flood control constraints emanating from the 8.5 Square Mile Area on water management to restoration in the central Everglades cannot be overstated and paves the way for additional water deliveries in the CEPP.

SOURCE: USACE and SFWMD, 2024.

NOTE: The combined seepage barrier along the 8.5 Square Mile Area would end 1.6 miles from the end of the 5-mile Rock Miners Seepage Wall.

SOURCE: Modified from Reynolds, 2022.

NOTES: Since the start of construction of the CEPP New Water seepage barrier in 2022, Angel’s well (red line), located outside the 8.5 Square Mile Area, has exhibited water levels up to 3 feet higher than those of a well just inside the new seepage barrier (LPG [black line]). In September 2022, the SFWMD’s 2.3-mile seepage barrier was completed, which together with a previously constructed interior seepage drainage system has managed flooding in the southern end of the 8.5 Square Mile Area (green line).

SOURCE: B. Mills, SFWMD, personal communication, 2024.

C-111 Spreader Canal Western Project

The C-111 Canal, originally designed to provide flood protection in Dade County, spurred agricultural development on lands to the east while draining water from the Southern Glades and Taylor Slough in Everglades National Park. A principal source of the freshwater in the canal is seepage from Everglades

National Park. Because seepage drains water from the park and alters the flow pattern of Taylor Slough, the C-111 Canal has had detrimental ecological and environmental effects on Taylor Slough and Florida Bay. The C-111 Canal also discharges large volumes of freshwater through the S-197 structure into Manatee Bay and Barnes Sound, while reducing overland flows that entered the central zone of Florida Bay, altering the natural salinity regime and ecology of those waters.

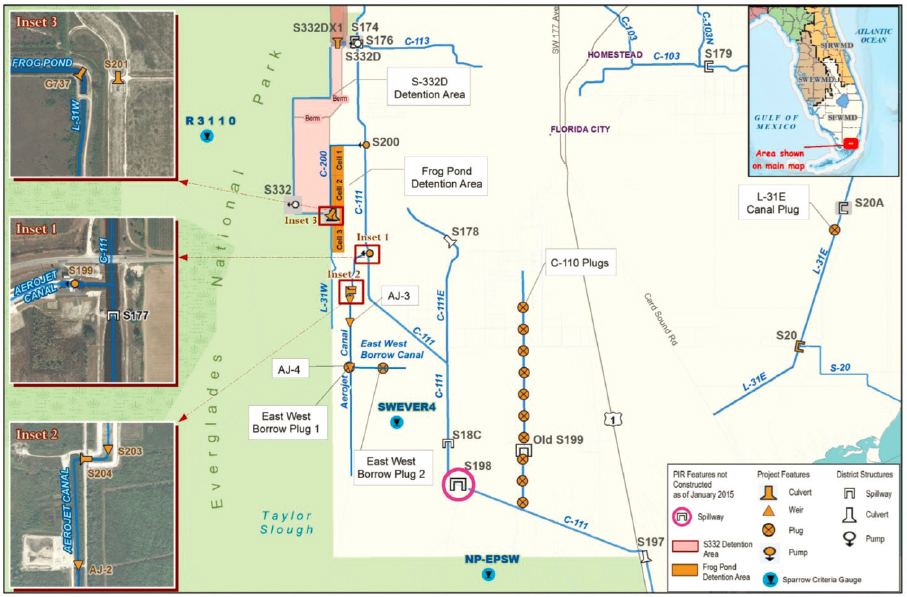

The construction of the C-111 Spreader Canal project (Figure 2-2, No. 6) was envisioned in two phases—the eastern and western projects. Planning for the features and objectives of the C-111 Spreader Canal Eastern project are part of the BBSEER project, discussed later in this chapter. The western project (Figure 2-15) was designed to help restore the quantity, timing, and distribution of water delivered to Florida Bay via Taylor Slough; improve hydropatterns within the Southern Glades; and lower coastal-zone salinities in central and eastern Florida Bay. The project was largely completed in February 2012 through expedited investment by the SFWMD, and operations began in June 2012. Construction of the final

SOURCE: Qiu et al., 2018.

project component—the S-198 Spillway (Figure 2-15)—is currently on hold. The SFWMD reports that it “may be implemented” if it is “anticipated to increase restoration and can be implemented without adversely impacting pre-project levels of flood protection” (Gottlieb et al., 2024); it remains unclear whether it will be constructed, because it is not included in the next 10-year schedule in the 2023 IDS (USACE, 2023e).

The C-111 Spreader Canal Western project pumps excess water from the canal into the 600-acre Frog Pond Detention Area and into the Aerojet Canal impoundment (Figure 2-15), thereby creating a 6-mile hydraulic ridge along the eastern boundary of Everglades National Park to reduce seepage from the park and improve the hydrologic conditions of Taylor Slough. Rather than a persistent feature, the hydraulic ridge is present and functions only when water is available to fill the detention area. The project is also intended to contribute to improved distribution of flows in the Southern Glades through emplacement of earthen plugs along the C-110 Canal and through modified operations of structures located principally along the southern segment of the C-111 Canal.

Annual SFWMD reports show prior year data on flow and stages (e.g., Gottlieb et al., 2024), but no recent long-term analysis is available on the hydrological or ecological outcomes of the project relative to expectations or baseline conditions. Gottlieb et al. (2024) report, “Within Taylor Slough, dry-season water levels have risen, and dry season tidal creek flows have increased” since operations began, although the data analysis is not presented. Given the overlap in downstream footprint of the project with other CERP and non-CERP projects, the SFWMD concluded that potential interactions will make it difficult to tease out specific direct benefits of the project (Gottlieb et al., 2024). The project features are operated as part of the COP, which outlines the integrated operations of CERP and non-CERP projects in the region. The benefits of the COP are discussed later in this section.

Biscayne Bay Coastal Wetlands, Phase 1

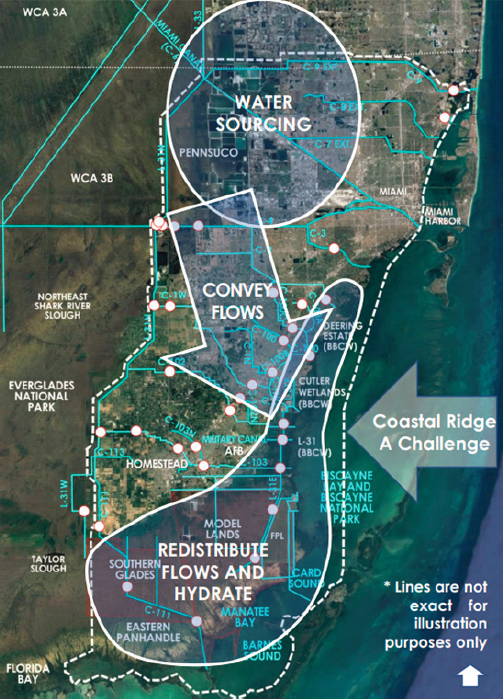

Historically, Biscayne Bay received freshwater from overland flow passing through the coastal ridge and wetlands, and from extensive groundwater seepage. As a consequence of historical hydrologic alteration and development, freshwater delivery to Biscayne Bay has been greatly reduced, particularly in the dry season, resulting in loss of wetlands and an increase in salinity along the western margin of the bay. At the same time, controlled freshwater pulse discharges as point sources create altered flow, salinity, and nutrient inputs into the bay. Freshwater wetlands in the Southern Everglades have been reduced in area, altered, and degraded because of water management practices, land development, and sea-level rise, and much of the Model Lands, Southern Glades, and South Dade Wetlands are drained. These factors have contributed to landward

expansion of saltwater and mangrove wetlands, including low-productivity, sparsely vegetated dwarf mangroves, and invasive exotic vegetation. The BBCW Project (Figure 2-2, No. 7) was developed to address these issues.

The primary goal of the BBCW Project is to reduce near-shore salinity and improve the ecological condition of wetlands, tidal creeks, and other habitats by increasing freshwater flows to Biscayne Bay and Biscayne National Park. The full BBCW Project, as outlined in the Yellow Book (USACE and SFWMD, 1999), envisioned restoration of wetland hydroperiods to 11,300 acres of the total 22,500 acres of wetlands. The footprint of BBCW Project Phase 1 is small. Its goals are to restore about 400 acres of freshwater wetlands and redistribute existing surface water to another approximately 2,000 acres in three geographically distinct components: the Deering Estate component, just north of the Biscayne Bay National Park, and the L-31E Flow-way and the Cutler Wetlands components, portions of which are within Biscayne National Park (Figure 2-16). The Deering Estate component was completed in 2012 and is operational. L-31E Flow-way is under construction, with some incremental benefits and completion expected in 2025 (Charkhian, 2023). No restoration progress is expected from the Cutler Wetlands component, which is only recently under construction, with completion estimated in 2025 (USACE, 2023e). The objectives of BBCW Project Phase 2 are being addressed through the BBSEER planning process, discussed later in the chapter.

Deering Estate.

The goal of the Deering Estate component is to rehydrate the wetland region east of Old Cutler Road, reduce point source discharges at S-123, and restore a more natural freshwater flow regime. The hydrologic objective was to redirect up to 100 cfs of water from the C-100A Spur Canal, via the S-700 pump station, to the coastal wetlands using nighttime pumping (see Chapter 5, Figure 5-8), thereby reducing point source freshwater discharges. However, in WY 2019 the SFWMD moved to continuous pumping at a minimum rate of 25 cfs to alleviate the hydrologic flashiness that occurred with intermittent pulsed releases (Charkhian, 2023). This change improved the hydration and increased the hydroperiod in the remnant wetlands over approximately 19 acres in this project area underlain by extremely porous limestone, which significantly reduced the groundwater and surface-water salinity in the wetland. Annual vegetation monitoring between 2019 and 2022 noted increasing numbers of willows and royal palm in the wetland sloughs (Charkhian and Niemeyer, 2023).

L-31E Flow-way.

The goal of the L-31E Flow-way component is to improve habitat conditions by diverting water that would normally be released through the L-31E Canal to the adjacent coastal wetlands via 10 newly constructed culverts, thereby lowering near-shore salinities. These culverts have been in place since 2010, but without completion of the associated pumps, it is difficult to maintain

SOURCE: Charkhian, 2024.

the canal stage high enough (stage target level is 2.2 feet National Geodetic Vertical Datum [NGVD]) to promote outflow through the culverts. The USACE is expected to finish construction of the L-31E Flow-way component in 2025, which will include a total of five pump stations (USACE, 2023e).

Several coastal wetland vegetation transects downstream from the L-31E culverts were sampled in 2022 and 2023. All transects remained dominated by a mangrove overstory, and a large decrease in mangrove with freshwater inflows has not been observed. New establishment of herbaceous species was limited and largely consisted of salt-tolerant species. The presence or increase of other freshwater species such as sawgrass outside of a few meters of established culverts was not observed (Charkhian, 2024). Charkhian (2024) stated,

As future deliveries of fresh water to the wetland are anticipated to substantially increase in the next two years, future monitoring efforts will determine whether this early lack of response is a result of the limited volumes of fresh water that have been delivered till now, or the strength of the opposing influences represented by rising sea level in Biscayne Bay, irrespective of any changes in freshwater delivery.

Regional Operations Plans

Kissimmee River Headwaters Revitalization Schedule

The Kissimmee Basin includes more than two dozen lakes in the Kissimmee Chain of Lakes, their tributary streams and associated marshes, and the Kissimmee River and floodplain (Figure 2-17). The Kissimmee River Restoration Project was authorized in 1992 with the goal of restoring more than 40 mi2 (or one-third) of the river-floodplain ecosystem and 44 miles of the river channel. Project features, which included backfilling 22 miles of the C-38 Canal, removing water control structures, and reconnecting remnant river segments, were completed in 2021, setting the stage for implementation of the new Headwaters Revitalization Schedule, which is beginning phased implementation in 2024.

Once fully implemented, anticipated in 2026, the new stage regulation schedule for the S-65 water control structure will allow water levels to rise up to 1.5 feet higher than the current S-65 schedule and will increase the water storage capacity of the Upper Kissimmee Basin by approximately 100,000 AF (Koebel et al., 2024). This increased capacity will allow releases to more closely approximate the historic flows needed for restoration of the Kissimmee River and its floodplain wetlands and is also expected to improve littoral zone conditions in Headwaters Lakes.

The ultimate goal of hydrologic restoration for the entire Kissimmee River is to restore the single, continuous floodplain inundation event that occurred

SOURCE: Betts et al., 2024.

most years prior to channelization that typically began late in the wet season, continued well into the dry season, and extended throughout all seasons in some years. Floodplain inundation supported wetland vegetation along the Kissimmee River floodplain and provided important foraging habitat for wading birds and waterfowl and nursery areas for native fish. Modeling results project that floodplain inundation will improve with the 1,400-cfs discharge plans while also improving conditions to the Headwaters Lakes (Koebel et al., 2024).

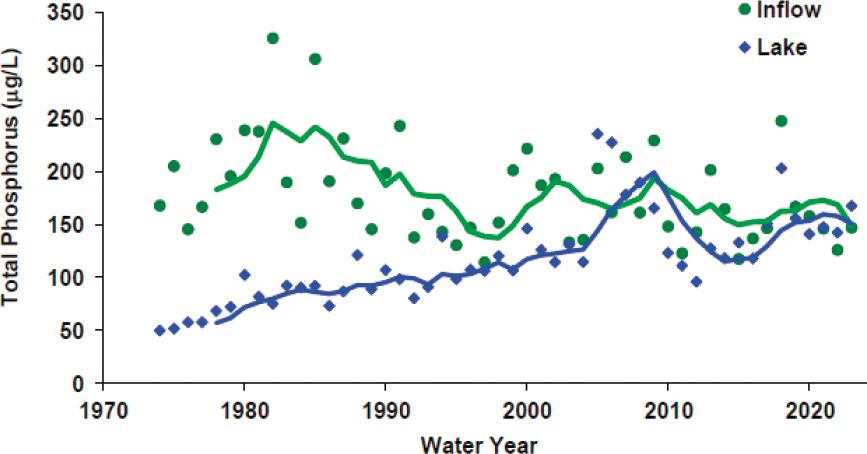

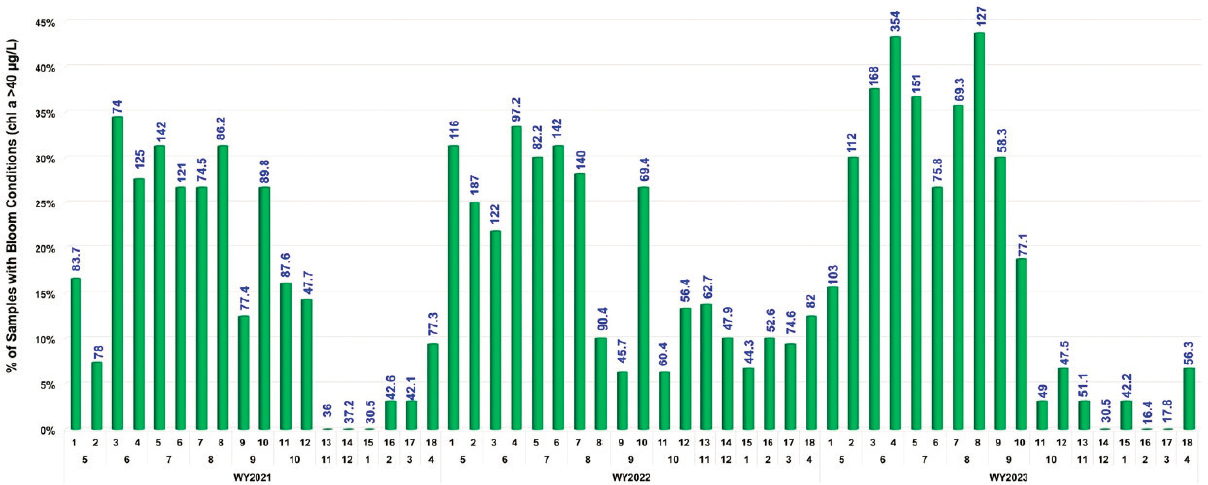

Lake Okeechobee System Operating Manual

Management of Lake Okeechobee is challenged by its fast inputs and limited managed outflow, allowing high precipitation events to raise water levels quickly. Prolonged high-water levels result in the loss of submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV) in the littoral zone (because of low light transmissivity) and extreme high-water levels can pose dike safety issues, thereby requiring releases to the northern estuaries. These releases alter salinity and increase turbidity and nutrient loads, which can negatively affect SAV in the estuaries and exacerbate harmful algal blooms. In contrast, extended periods of low precipitation can lower water levels in the lake, leading to expansion of invasive species in the littoral zone and threats to water supply deliveries to utilities, agricultural producers, and residential populations (see NASEM, 2018, for in depth discussions of Lake Okeechobee and the northern estuaries).

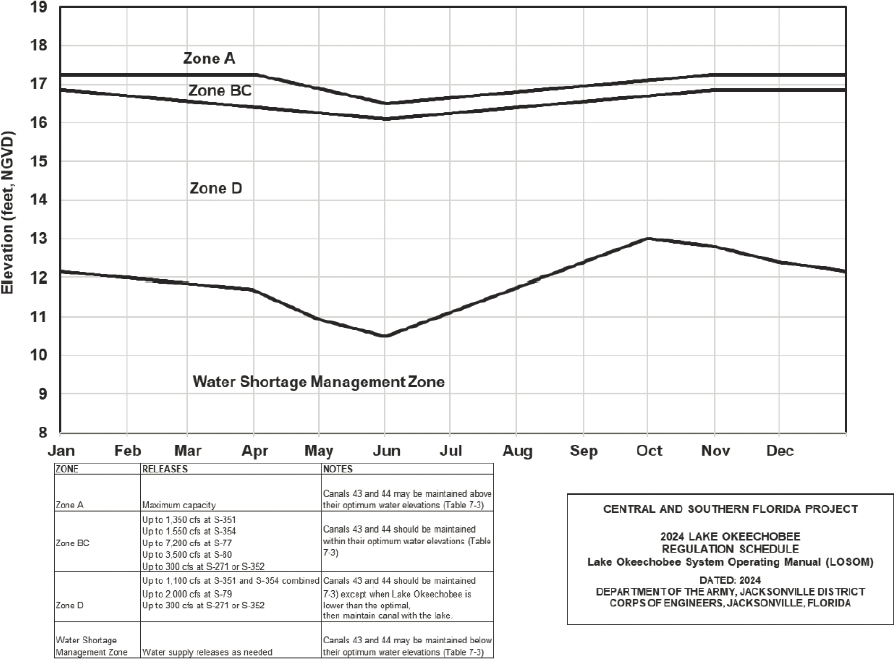

In 2022, after extended stakeholder input, the USACE released a draft of LOSOM as the updated plan to manage the water levels in the lake after completion of the Herbert Hoover Dike rehabilitation efforts (USACE, 2022b). Zone D of the proposed operating schedule provided considerable flexibility compared to previous plans as to when to hold or release water from the lake, but with this flexibility comes uncertainty regarding the criteria for operational decisions within Zone D (Figure 2-18). LOSOM also resulted in substantially less water storage (between 460,000 and 800,000 AF) compared to the operations in place when the CERP was originally designed (for more information, see NASEM, 2023). Implementation of LOSOM was scheduled for March 2023 but was delayed pending final agency review after recent consultation and a biological opinion from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS, 2023).

The LOSOM Final Environmental Impact Statement (EIS; USACE, 2024b) was published in May 2024. The EIS reemphasizes the USACE operational strategy to balance the needs of managing flood risk, water supply, navigation, recreation, and the ecological health of fish and wildlife. The committee acknowledges the greater flexibility in LOSOM to make releases to improve water supply and enhance fish and wildlife, as well as use whole-system behavior to make

NOTES: If lake level exceeds the top line bordering Zone A, water must be released to the northern estuaries at maximum discharge capacity. In Zone BC, discharge levels are high but below maximum (≤7,200 cfs to the Caloosahatchee River Estuary and ≤3,500 cfs to the St. Lucie Estuary) to lower lake levels. Within Zone D, no water is discharged to the St. Lucie Estuary and up to 2,000 cfs may be discharged to the Caloosahatchee River Estuary.

SOURCE: USACE, 2024b.

real-time decisions, because of the latitude in Zone D. NASEM (2023) recommended that the USACE implement a process for periodic multi-stakeholder review of Lake Okeechobee operations relative to the objectives of LOSOM to build confidence that the flexibility of the new operational schedule is being used as designed and to support learning to enhance future decision making. USACE (2024b) noted that it plans to hold three seasonal periodic scientist call meetings per year for agency and stakeholder communication and input.

The Combined Operational Plan

The COP is a comprehensive, integrated water control plan that defines the operations of the constructed features of the Modified Water Deliveries to Everglades National Park (Mod Waters) and C-111 South Dade projects (Figure 2-13) and other water management structures in the region. These non-CERP projects whose capabilities it incorporates are considered foundation projects for the CERP because they alter the delivery and flow of existing water in ways that are critical to the CERP’s capacity to deliver additional flow volumes and restoration benefits. In addition, completion of Mod Waters and its operations plan was required before federal funding could be appropriated to begin construction of the CEPP. Therefore, the implementation of the COP marks not only the largest step by far toward restoring the hydrology and ecology of the central Everglades yet achieved but also the beginning of the next phase of the restoration of the heart of the Everglades embodied in the CEPP.

Two features of Mod Waters and other related projects are especially critical to the capacity of the COP to make significant changes to the hydrology of the central Everglades. First, raising the Tamiami Trail and bridging extensive portions of it enables increased flows into Northeast Shark River Slough and Everglades National Park, and much more as sheet flow (Box 2-1). Second, seepage management and flood mitigation features along the eastern boundary of Everglades National Park (Figure 2-13) reduced flood risk management constraints that limited flows into Northeast Shark River Slough. The C-111 South Dade Project improved seepage management along the eastern boundary of Everglades National Park further south, enabling more flow through Taylor Slough to Florida Bay, while continuing to honor flood risk management constraints for the agricultural lands east of the park (USACE, 2022c). The C-111 Spreader Canal Western project extends this hydraulic ridge southward, providing additional restoration benefits to Taylor Slough.

The ongoing ecological degradation of the central Everglades (see NRC, 2012 for a review) has long been a major concern motivating restoration efforts, and management of water in this area is a source of controversy. The COP is the latest in a series of water management plans that attempts to address the issues in this region. The development of the COP was informed by data gathered during a period of incremental operational testing, beginning in 2015. Thus, the hydrologic and ecological changes discussed in this section reflect incremental operational changes from 2015 to 2020 and full implementation of the COP in September 2020, which were made possible by the new infrastructure available from the Mod Waters, C-111 South Dade, and Tamiami Trail Next Steps projects.

A comprehensive assessment of observed COP benefits can be found in the COP Biennial Report (USACE et al., 2023a), which summarizes COP operations,

BOX 2-1

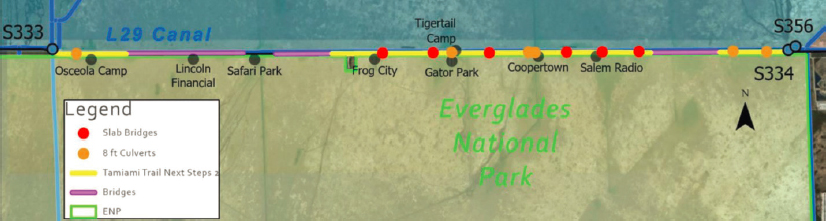

Tamiami Trail Next Steps Project

The 10.7 miles of the Tamiami Trail between the L-31N and L-67 extension levees have been an impediment to surface flow from WCA-3 into Northeast Shark River Slough located in Everglades National Park since the completion of this highway in 1928. Reducing the impact of this barrier has been an important component of the restoration. The Modified Water Deliveries Project created a 1-mile bridge, completed in 2013, near the eastern end of this portion of the Trail. Phase 1 of the Tamiami Trail Next Steps project, completed in 2019, addressed an additional 2.6 miles of highway with 2.3 miles of bridging at the western end of the 10.7 miles of the Trail (Figure 2-19). The Tamiami Trail Next Steps Phase 2 project will reduce the impact of the remaining 6.7 miles of highway on sheet flow through the addition of six new 60-foot-wide slab bridges, improvements to seven culverts, and raising of the highway in unbridged segments. Phase 2 construction began in 2021 and is projected to be completed in 2026 (USACE, 2023e). With the completion of this project, the entire 10.7 miles of the Trail will have been modified, which will enable raising of the maximum water level in the L-29 Canal to 9.7 feet to accommodate the CEPP, which will have a profound effect on capacity to manage water moving through WCA-3 into Everglades National Park. At that time managers anticipate implementing a new water management plan (CEPP 1.0) that will replace the COP and that incorporates these new features.

SOURCE: Johnson, 2020.

the USACE decision-making rationale for any deviations, and the hydrologic and ecosystem status for the period September 1, 2020, through April 30, 2022. The COP Biennial Report seeks to address whether the plan is achieving its objectives and whether adjustments are recommended. The report also evaluates the adaptive management uncertainties identified in the design of the COP based on recent monitoring results.

Hydrologic responses.

The COP Biennial Report (USACE et al., 2023a) presents an analysis of the hydrologic performance of the COP, employing the performance metrics used in the development of the COP as a reporting and evaluation framework. Monitoring results from before and after COP implementation and simulated COP performance from the Regional Simulation Model for the Glades and Lower East Coast Service Areas (RSM-GL) are compared. This comparison enables assessment of actual COP performance relative to the expectations based on modeling, and thus provides insight on the predictive performance of the modeling in terms of recent historical conditions (termed baseline, WY 2002–2015), which sheds light on the actual improvements achieved on the ground. Although encompassing only approximately 2 years of full COP operations, the report includes both a wet (WY 2021) and dry water year (WY 2022), signaling some early hints at COP performance. The biennial reports will be increasingly informative and important as the period of COP implementation lengthens.

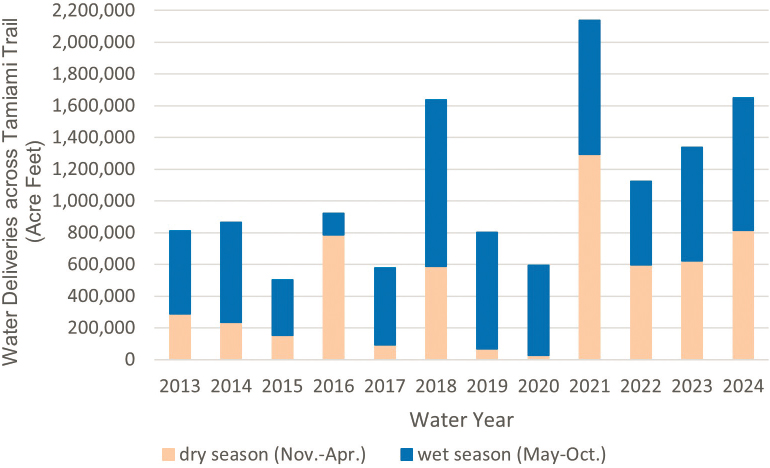

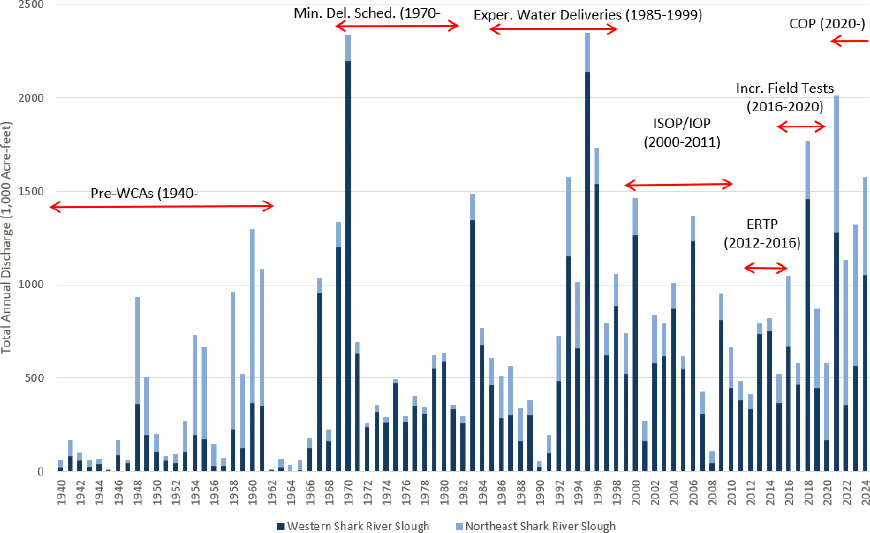

For the current report period, the hydrologic results have been consistent with or better than the expectations based on model simulations and better than historical conditions. Even in the dry year of WY 2022, the water deliveries across Tamiami Trail were well above the typical deliveries prior to 2016 (note that the period after 2016 and prior to the COP consisted of incremental field testing of the Mod Waters features and emergency deviations and is less useful for comparisons) (USACE et al., 2023a). As the committee noted previously, the COP has been remarkably successful so far in not only increasing water deliveries across Tamiami Trail, particularly during the dry season (Figure 2-20), but also restoring the historical distribution of those flows between Western and Northeastern Shark River Slough (Figure 2-21; NASEM, 2023).

Water deliveries to Taylor Slough have also shown improvements from COP implementation to date. The longer hydroperiods have been observed relative to the pre-2016 baseline for most of the Everglades National Park region and especially in Northeastern Shark River Slough, Taylor Slough, and the western and eastern marl prairies. Again, the results compare well with the modeled expectations and generally show improvement relative to the historical baseline. Dry days and risk of soil oxidation within Everglades National Park have been reduced under the COP relative to the baselines even in the dry year, although risk of soil oxidation increased as was anticipated in north-central WCA-3A. In terms of increases in freshwater flows to Florida Bay, the results are modest and reflect the need for additional projects to come online before improvements can be expected there (USACE et al., 2023a). Overall, the early hydrologic results from the COP are promising and provide confidence in the modeling, coordination, and evaluation process used to produce it.

SOURCES: Data from Velez, 2024, and L. Do, USACE, personal communication, 2024.

Ecological responses.

To assess ecological performance, the COP Biennial Report (USACE et al., 2023a) employs a similar process as that used to assess hydrological performance. Of the four ecological performance measures monitored—freshwater fish, tree islands, wood stork and wading bird nesting, and slough vegetation—there are, as yet, too few data to definitively assess COP performance for freshwater fish and tree islands. For wood stork and wading bird nesting (see also below), the variation in rainfall over the period of review was deemed too large to evaluate the impact of the COP (USACE et al., 2023a). The fourth performance measure, slough vegetation, however, is highly informative. Coincident with increased hydroperiods in Northeastern Shark River Slough under the incremental field testing and the COP, long hydroperiod species such as sawgrass and slough species such as Eleocharis are expanding (USACE et al., 2023a). Nocentini et al. (2024) further document this pattern, including transitions to wetter plant communities along the gradient from dry marl prairie to beaksedge (Rhynchospora tracyi) marsh to sawgrass marsh to slough communities, as well as loss of marl prairie species. These results indicate that a predicted ecological benefit of the COP is being achieved.

NOTES: The red arrows demarcate the water management plans that governed water flows through these pathways from 1940 to 2024. These data highlight the increasing flows into Northeast Shark River Slough in the COP.

SOURCES: R. Johnson, DOI, and E. Stabenau, National Park Service, personal communication, 2024.

Additional ecological monitoring associated with the COP addresses impacts on threatened and endangered species (see Table 2-5 for the committee’s summary of results of monitoring for the Cape Sable seaside sparrow [Ammodramus maritimus mirabilis], Everglade snail kite [Rostrhamus sociabilis plumbeus], and wood storks [Mycteria americana]) related not only to performance measures but also to criteria for incidental take, exceedances of which could require reinitiating consultation with the FWS over COP operations.2 The prior period

___________________

2 Several of the criteria require an exceedance in 2 consecutive years to reinitiate consultation. Exceedances may also be attributable to climatic variability rather than operations of the COP. For example, if an exceedance did occur but localized rainfall was the cause of the exceedance, then re-initiation of consultation may not be warranted because the root cause was not attributable to operations (G. Ralph, USACE, personal communication, 2024).

TABLE 2-5 Committee Assessment of COP Effects on Threatened and Endangered Species Relative to 2016–2020 Conditions

| Type | Target/Criterion | Baseline Performance (2016–2020) | COP Performance (2021–2023) | Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cape Sable Seaside Sparrow | ||||

| Take | Population size | Criterion met 4/4 (100%) | Criterion met 3/3 (100%) | Criterion always met, close to exceedance 1/5 baseline and 2/3 COP years, no improvement over baseline |

| Parameter | Nesting season dry days in 6 subpopulations | Target met 12/30 (40%) | Target met 3/10 (30%) | Target only sometimes met, no improvement over baseline |

| Parameter | 4-year average hydroperiod in 6 subpopulations | Target met 8/30 (27%) | Target met 2/10 (20%) | Target met regularly 1 subpopulation, rarely in 5, no improvement over baseline |

| Snail Kite | ||||

| Take | Maximum dry season water level (4/15–5/31) | Criterion met 1/5 years | Criterion met 2/3 years | Criterion sometimes met, improvement over baseline |

| Take | Pre-breeding maximum water level (6/1–12/31) | Criterion met 3/5 years | Criterion met 2/2 years | Criterion usually met, improvement over baseline |

| Take | Recession rate (maximum stage difference) | Criterion met 18/20 (90%) at 4 gages | Criterion met 6/12 (50%) at 4 gages | Criterion sometimes met, less often compared to baseline |

| PM | Dry season water level (5/1–6/1) | NA | Target met 56%, 2%, 100% days 2021–2023 | Variable success meeting target depending on rainfall regime |

| PM | Pre-breeding water level | NA | Target met 2/2 years | Target always met |

| PM | Optimal and suboptimal (but suitable) weekly recession rates during nesting season (1/1–6/1) | NA | Over 3 years, 3% optimal, 30% suboptimal, 67% undesirable | Suboptimal target sometimes met, optimal target rarely met |

| Type | Target/Criterion | Baseline Performance (2016–2020) | COP Performance (2021–2023) | Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wood Stork | ||||

| Take | Nesting season maximum water level in WCA-3A (3/1–5/31) | Criterion met 9/15 (60%) months | Criterion met 8/9 (89%) months | Criterion almost always met, improved over baseline |

| PM | Optimal and suboptimal (but suitable) weekly recession rates during nesting season (1/1–6/1) | NA | Over 3 years, 5% optimal, 82% suboptimal, 14% undesirable | Suboptimal target almost always met, optimal target rarely met |

| PM | Maximum undesirable recession rates during nesting season (1/1–6/1) | NA | Target met all weeks 2021 and 2022, met 20/22 weeks 2023 | Target almost always met |

| PM | Optimal and suboptimal (but suitable) water depths in the core foraging areas of active nesting colonies | NA | Generally met in 2021, often not met in 2022, 2023 | Target sometimes met |

| PM | Maximum conversion of short to long hydroperiod wetlands within core foraging areas | NA | Greatly exceeded in 2021, 2022 (no data for 2023) | Target appears unattainable |

NOTES: Three types of measure are included: criteria for incidental take (Take), performance measures (PM), and hydrological parameters indicating potential for incidental take of Cape Sable seaside sparrows (Parameter). Results are shown for the incremental testing baseline period (baseline performance) and for full COP operations (COP performance) and summarized in Assessment.

SOURCES: Data from USACE, 2023f, 2023g; USACE et al., 2023a.

of incremental testing (2016–2020) was used as the baseline for comparisons to COP performance (2021–2023), limiting the ability to assess the full benefits of the COP relative to previous management plans (NASEM, 2021). No comparisons to a baseline have been made for performance measures for threatened and endangered species; performance is instead assessed in terms of success in meeting targets.

The monitoring results summarized in Table 2-5 highlight the challenges that the COP faces in meeting precise, complex targets over extended periods, such as water levels and especially recession rates during the nesting season for snail kites and wood storks. The COP and the infrastructure it employs likely lack the capacity to adjust sufficiently to achieve such precise goals under all rainfall regimes, a conclusion evidently reached by FWS in its decision not to reinitiate consultation in response to exceedance of incidental take of snail kites based on recession rates (Table 2-5). Impacts on wood storks and snail kites were not expected to be sufficiently adverse to result in constraints on operations, and no constraints have been placed on operations. For these two species, performance related to incidental take criteria, as anticipated, has instead improved under the COP relative to the 2016–2020 baseline, with the exception of the recession rate criterion for kites.

Results for the Cape Sable seaside sparrow present a very different picture. Simulations of COP performance predicted that the hydrologic targets for the sparrow will not be met (USACE, 2020a), and monitoring confirms this prediction. If anything, performance has declined under the COP relative to baseline (Table 2-5). The evidence is abundant that the COP is reducing short hydroperiod wetlands (see above; see also NASEM, 2023). That the acres of short hydroperiod wetlands within the core foraging areas of stork colonies experiencing long hydroperiods exceeded the target by an order of magnitude in each of the first 2 years of the COP (USACE, 2023g) adds to this evidence. Because of these changes, sparrows are losing habitat in the areas they currently occupy, and to date, they have not colonized new suitable habitat created by the COP. Data as of July 2024 indicate that their estimated population size has fallen below the threshold for incidental take (2,387 sparrows) (M. Meyer, FWS, personal communication, 2024). The future of the sparrow under the COP and subsequently the CEPP is an issue that requires creative solutions, sooner rather than later.

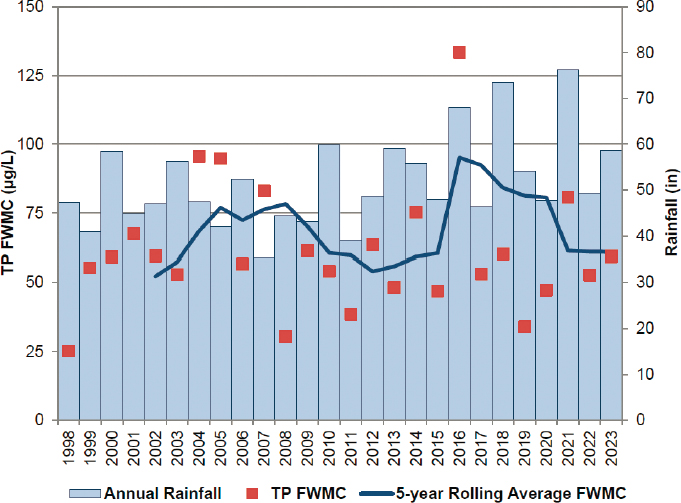

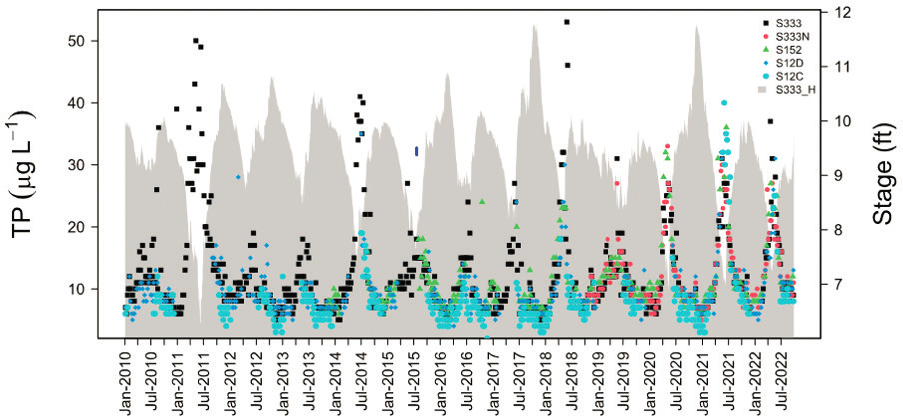

Water quality responses.

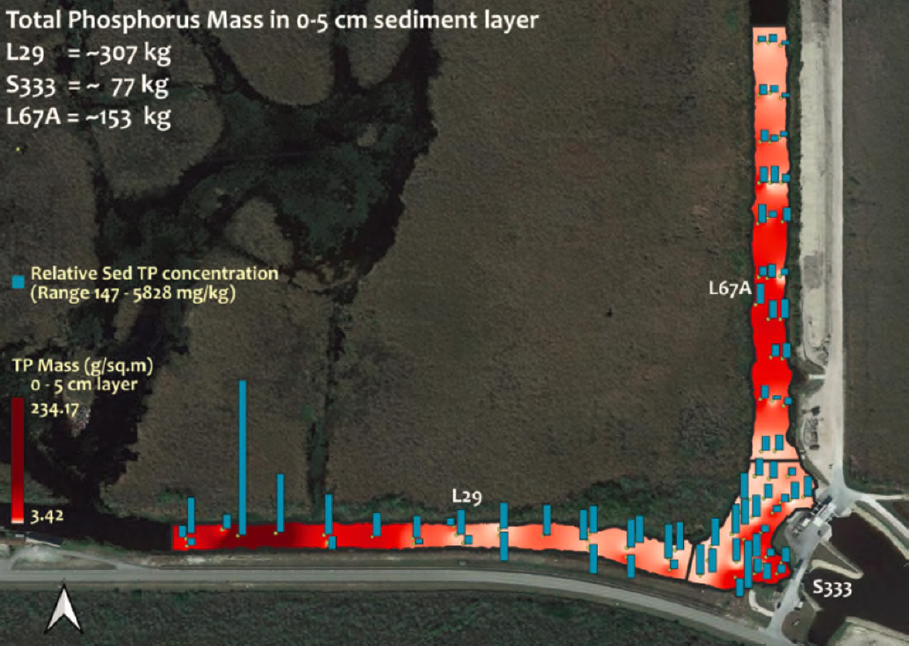

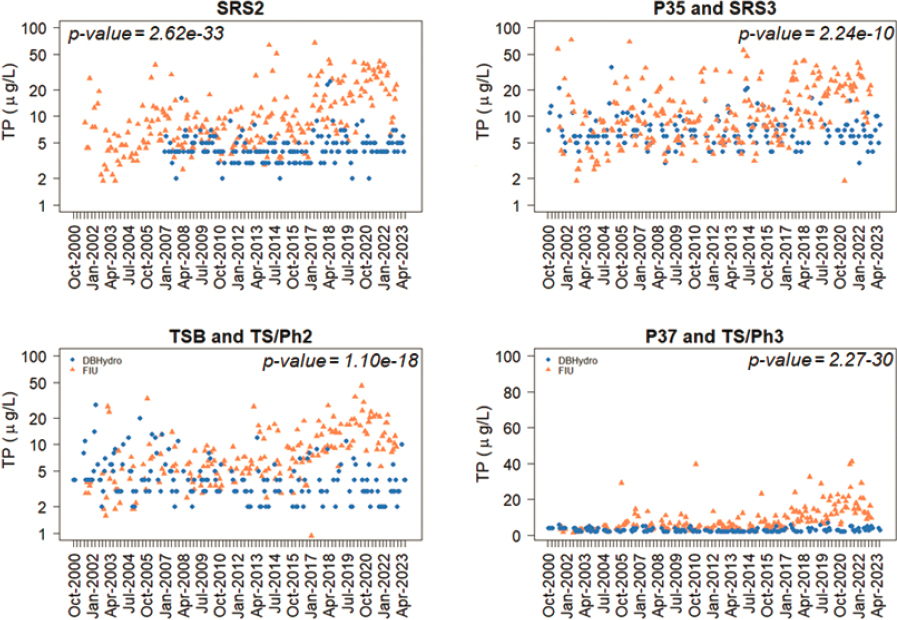

The 2023 COP Biennial Report highlighted ongoing water quality concerns, noting an exceedance in the 12-month average phosphorus concentration for inflows to Shark River Slough during WY 2019. Since then, exceedances have occurred in WY 2021–2023 (Qiu, 2024a,b).

Uncertainty #16b in the COP adaptive management plan (USACE, 2020a) specifically addressed water quality changes due to COP operations:

Water Quality in Northeast Shark River Slough: Will there be downstream biogeochemical effects associated with modifying inflows and hydrologic conditions in [Everglades National Park] ENP, that result in detrimental effects on nutrient movement, availability, and ecological responses?

During the reporting period, monitoring data were analyzed to investigate the potential to reduce concentrations by shifting flows from the S-333 structure to the S-333N structure and/or making adjustments to the S-12 structures, but the analysis showed that such changes would not reduce total phosphorus (TP) concentrations. Concerns were raised about water quality resulting from S-333 operations, but during the COP biennial reporting period, management options were not implemented. Water quality issues associated with increased restoration flows are discussed in more detail later in the chapter.

Summary of COP results.

The initial monitoring results indicate that the COP has met expectations in changing the quantity, distribution, and seasonal patterns of flow and improved conditions relative to the baseline period. Initial results also indicate that these hydrologic changes are producing some of the predicted broader ecological responses that are COP objectives, as illustrated by changes in plant communities and risk of soil oxidation. The COP has achieved much less success with more complex objectives that involve creating fairly precise hydrologic conditions over extended periods of time, as illustrated by recession rates and water levels during the nesting season for threatened and endangered species. Thus, the COP is proving to be what it was intended to be—not a complete solution but rather the first major step toward restoring the central heart of the Everglades. Additional efforts will likely be needed to sustain the Cape Sable seaside sparrow, including but not limited to translocation. The first COP Biennial Report is an effective means of conveying progress toward restoration that should be emulated through the remaining years of the COP and beyond.

CEPP 1.0 operational plan.

Lessons learned from the COP can be applied to the next system operating plan, CEPP 1.0, which is currently in planning to adapt operations to recently completed or soon-to-be-completed CERP features. CEPP 1.0 will incorporate CEPP components scheduled for completion by 2025, including CEPP New Water and several CEPP South features.3 Several non-CERP projects will also be included for the development of this regional operations

___________________

3 These features include the S-333N and S-355W Spillways; the S-631, S-632, and S-633 culverts through the L-67A levee; and the S-152 culvert and L-67 levee gap from the Decomp Physical Model.

plan, including the Tamiami Trail Next Steps Phase 2 project (Box 2-1), the 2.3-mile seepage barrier adjacent to the 8.5 Square Mile Area constructed by the SFWMD, the 5.0-mile CEPP New Water seepage barrier (Figure 2-13), and LOSOM (Figure 2-18). Crucially, CEPP 1.0 will raise the constraint on water levels in the L-29 Canal from 8.5 up to 9.7 feet, enabling movement of even higher flows of freshwater through the central Everglades and into Everglades National Park. Thus, CEPP 1.0 represents a major increment in the restoration of historic flow volumes and distribution beyond that achieved by the COP. Currently alternatives are being developed and compared, with the expectation that CEPP 1.0 will be implemented in 2026 (USACE and SFWMD, 2024).

Authorized CERP Projects Not Yet Constructed or Fully Operating

Six CERP projects are actively under construction, of which four—the C-43 Reservoir, IRL-South, the C-11 Impoundment, and the CEPP (including CEPP South, CEPP North, and CEPP EAA)—are too early in their construction to have documented restoration benefits. Additionally, the Loxahatchee River Watershed project has been authorized, but construction has not yet begun. These projects are described briefly here to understand the context of implementation progress.

C-43 Reservoir

Early in the 20th century, the course of the Caloosahatchee River was deepened and straightened, and canals were excavated in the river basin that connected the river to Lake Okeechobee and drained agricultural lands and urban areas. As a result, during prolonged dry periods, freshwater flow to the estuary is greatly reduced, and saline water can migrate far up the river, killing beds of freshwater submerged plants. Conversely, during periods of heavy rainfall, large volumes of nutrient- and sediment-rich freshwater are transported into the Caloosahatchee River estuary, affecting habitat quality for seagrasses, oysters, and other aquatic organisms. The Caloosahatchee River (C-43) West Basin Storage Reservoir (Figure 2-2, No. 8) is a CERP project designed to impound up to 170,000 AF of stormwater runoff from the C-43 drainage basin or from Lake Okeechobee during wet periods (USACE and SFWMD, 2010), hence protecting the estuary from excessive freshwater. During dry periods, this stored water can be released to supplement low river flows to maintain optimal salinity levels in the estuary. Additionally, the SFWMD is planning to construct a non-CERP in-reservoir alum treatment system to reduce phosphorus loading to the Caloosahatchee River estuary to address concerns that storage of high phosphorus water in the reservoir could contribute to algal blooms (J-Tech, 2020). Reservoir construction has been delayed by the need to replace the contractor (A.B. Williams, 2023),

although completion is still anticipated in December 2025 (USACE, 2024d), and the SFWMD expects to begin filling the reservoir in late 2024 (Parrott, 2024). It is too soon to realize natural system benefits from this project.

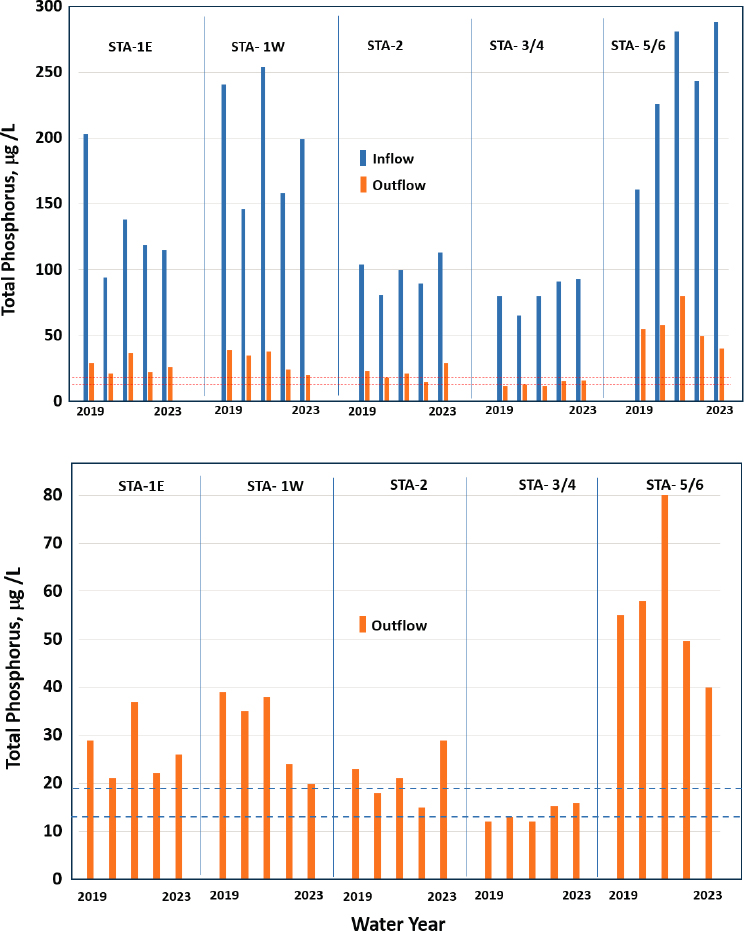

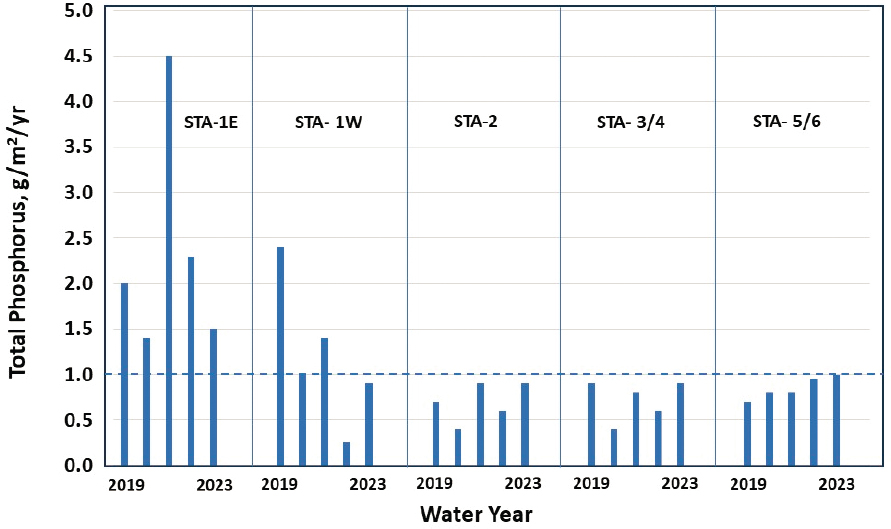

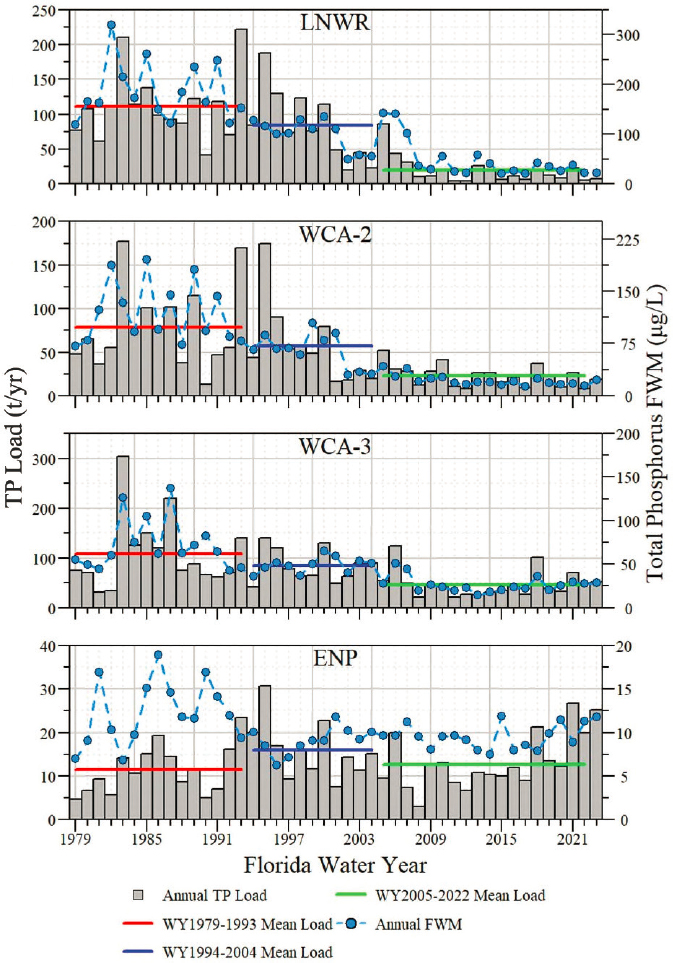

Indian River Lagoon-South