Progress Toward Restoring the Everglades: The Tenth Biennial Review - 2024 (2024)

Chapter: 5 Adaptive Management and Use of New Information in Decision Making

5

Adaptive Management and Use of New Information in Decision Making

When the U.S. Congress approved the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP) in the Water Resources Development Act of 2000 (WRDA 2000), the Central and South Florida Comprehensive Review Study (or Yellow Book; USACE and SFWMD, 1999) was recognized as providing a general outline for restoration of the Everglades rather than a detailed restoration plan. In consideration of Congress’s direction to move forward in the face of uncertainties, adaptive management was identified and authorized in the legislation as a CERP program element and mechanism to incorporate emerging scientific information into the plan and to address unforeseen consequences of restoration projects. Congress subsequently approved funding for an Adaptive Management and Monitoring program in WRDA 2000, and the 2003 Programmatic Regulations (33 CFR §385.31) directed the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) to adopt an adaptive management approach.

The concept of adaptive management emerged in the 1970s as an approach to address increasingly complex resource management issues. Adaptive management offers a means to proceed amid uncertainty through the iterative refinement of management actions, ideally based on experimentation and a rigorous monitoring and science program (Lee, 1999; Walters and Holling, 1990). Of the many applications of adaptive management, the most effective ones have well-structured processes that include the following:

- management objectives that are regularly revisited and accordingly revised,

- a model or models of the managed system,

- a range of management choices,

- the monitoring and evaluation of outcomes,

- mechanisms for incorporating learning into future decisions, and

- a collaborative process for stakeholder participation and learning (NRC, 2004b).

Through effective application of such processes, decision making moves from trial and error to learning by doing based on modeling, monitoring, assessment, reevaluation, research, and field-based pilot projects, thus improving management by minimizing costly mistakes and reducing operational and ecosystem risk associated with unintended outcomes. The literature is replete with diagrams outlining the iterative adaptive management process, and one of the more detailed examples is shown in Figure 5-1.

SOURCE: DOI and DOC, 2009.

Effective adaptive management programs require governance authority and policy-level support and direction as well as clear and agreed-upon adaptive management processes and objectives. These processes are critical to facilitate the timely incorporation of new information and to expeditiously adjust and improve management to better meet program goals. Importantly, effective programs and processes require general agreement among agencies and stakeholders on why adaptive management is being implemented. For example, is the objective of adaptive management to better achieve the outcomes expected at the outset of the restoration or modified outcomes based on new information, or to maximize the benefits of management actions? Without clear, agreed-upon objectives and processes, adaptive management programs will face delays and inaction.

Twenty-five years have passed since the Yellow Book was published, and although much has been learned about the Everglades, adaptive management remains central to enhancing restoration outcomes. As multiple CERP and non-CERP projects are being implemented, opportunities exist to better understand the interconnected hydrologic, geomorphic, geochemical, and biologic processes necessary to sustain the Everglades and inform future decisions on restoration design and operations. Adaptive management built on strategically designed monitoring, research, and predictive models can identify feedback mechanisms and thereby improve understanding of system responses under different operational actions and climate regimes—supporting progress toward CERP goals while building a culture of cooperation, communication, and long-term support for restoration among scientists, restoration practitioners, decision makers, Tribes, and stakeholders.

In this chapter, the committee evaluates the status and effectiveness of adaptive management and incorporation of new information in the CERP to support learning and improve decision making after an initial project plan (i.e., a Project Implementation Report [PIR]) has been developed. The committee reviewed the CERP agencies’ use of new information from monitoring, modeling, and research to inform decision making at four different scales, some of which may not be considered adaptive management by all agencies but nevertheless play an important role in achieving restoration outcomes.

- Project-level adaptation during design and construction. After the initial project planning and authorization, engineers develop specific designs that incorporate additional detail that was not available or included in the original PIR. New information gained and additional detailed analysis between the development of the PIR and the final design can lead to project refinements. All changes must be approved according to USACE policy.

- Project-level adaptive management after operations begin. After construction of a project (or project component) is completed and operation ensues, the USACE project-level adaptive management process can begin,

- including monitoring, assessment, and modifications to operations or the design if warranted. Extensive guidance documents (e.g., RECOVER, 2011, 2022l, 2022m, 2022n; USACE and SFWMD, 2018) have been developed, and all CERP projects authorized after the guidance documents were released must have an adaptive management plan.

- Operational adaptation at regional scales. Regional systems have operational plans to manage the delivery of water under changing conditions. While operational plans are designed to cover a wide range of conditions, new information about species or habitat conditions or extreme hydrologic events can create a need to deviate from the existing plan over the short term and/or adapt the operational plan over the long term through periodic revisions. “Managing adaptively” is a term used to describe leveraging new science and information to make flexibility-based decisions and improve operations.

- Program-level adaptive management. The CERP originally included 68 projects that were designed to function collectively to support restoration of the remnant Everglades ecosystem while balancing requirements for flood control and water supply needs. Program-level adaptive management represents system-level adjustments to new information based on an assessment of expected progress of the CERP relative to the original goals.

In this chapter the committee discusses the evolution of adaptive management in the CERP and then evaluates the effectiveness of adapting to new information at these four scales. Specifically, the committee’s review focuses on assessing how CERP projects and the overall program are using new information to improve their design, development, construction, and operation. Finally, the committee discusses the key elements of the science enterprise (see also NASEM, 2023) that are essential to support adaptive management and recommends approaches to strengthening them.

ADAPTIVE MANAGEMENT PROCESS GUIDANCE FROM RECOVER

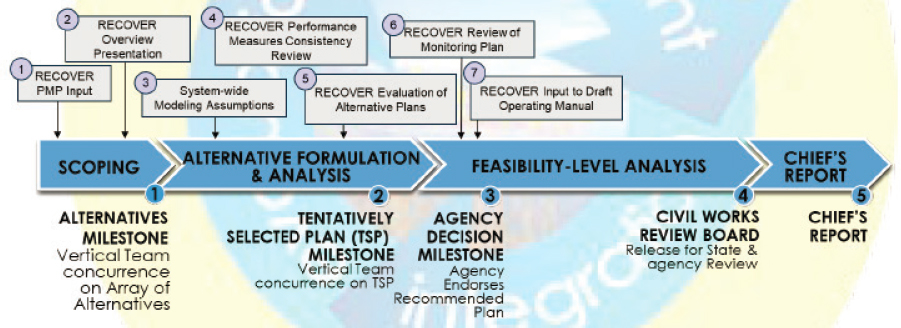

RECOVER (see Appendix A) has assumed much of the responsibility for fulfilling the requirement that the CERP employ an adaptive management approach. In 2006, RECOVER produced an early vision for adaptive management that emphasized systemwide (i.e., program-level) adaptive management and included elements of project-level adaptive management (RECOVER, 2006a). The CERP Adaptive Management Strategy was visualized in four stages (see also Figure 5-2):

- Planning, during which uncertainties are identified;

- Performance assessment, during which monitoring is conducted and the outcomes of restoration investments are assessed using either project-level

NOTES: Box 4 in the diagram differs from the Periodic CERP Update, which is defined in the Programmatic Regulations (33 CFR Part 385) as “the evaluation of the Plan that is conducted periodically with new or updated modeling that includes the latest available scientific, technical, and planning information.” Under the Programmatic Regulations, a separate Comprehensive Plan Modification Report is required to make changes to the overall CERP.

SOURCE: RECOVER, 2006a.

- monitoring or the CERP Monitoring and Assessment Plan (RECOVER, 2004, 2006b, 2009);

- Management and science integration, which involves communication of new information and its implications to management; and

- Decision making, during which modifications to the CERP may be made.

However, this early broad vision provided little detail on the specifics of each stage or their interconnections.

Detailed Project-Level Implementation Guidance

Although the CERP adaptive management strategy articulated the importance of adaptive management at the project level, the early CERP projects (e.g., Picayune Strand, Indian River Lagoon) did not include formal adaptive management plans in their PIRs. In 2009, the USACE required adaptive management plans in all CERP projects (USACE, 2009), and the Adaptive Management Integration Guide (RECOVER, 2011) was developed to provide specific process guidance on how to integrate adaptive management within the USACE project planning process. This includes guidance for developing project-level adaptive management plans to facilitate future decision making. These project-level plans identify critical uncertainties, and for each uncertainty the plans document indicators to assess performance, thresholds for when corrective action should be taken, and management options matrices describing corrective actions if projects are not meeting performance targets.

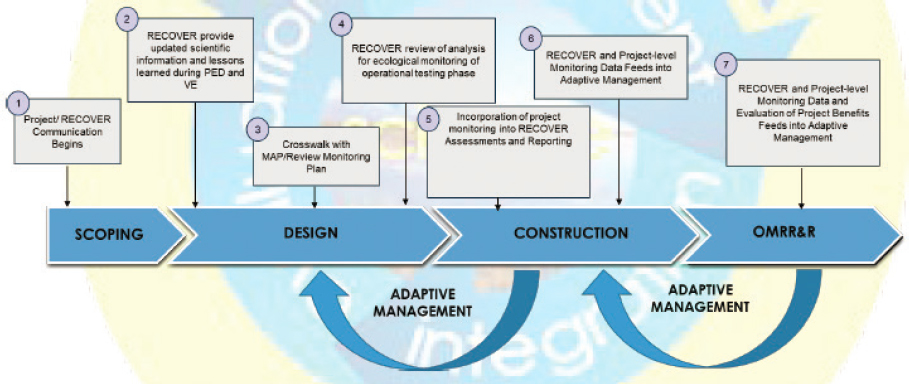

CERP Guidance Memorandum 66 (USACE and SFWMD, 2018) was developed to provide additional direction and detailed process guidance for how RECOVER helps provide integration of new science and information into projects during post-authorization design, construction, and operations. A key element of this guidance is that each project is assigned a Point of Contact from RECOVER who monitors and supports the interactions of RECOVER with the Project Delivery Team. Additional recent detailed guidance (RECOVER, 2022a-n) describes Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for points of interaction of RECOVER with Project Delivery Teams during project planning (i.e., prior to project authorization; Figure 5-3) and during project implementation (i.e., post-authorization; Figure 5-4).

The detailed adaptive management guidance is conceptually consistent with the original vision for CERP adaptive management, describing in detail the roles of the various entities involved (e.g., project teams, RECOVER, decision makers) and their interactions depicted in Figure 5-2. The guidance focuses on the interactions of RECOVER with project teams and its role and responsibilities as the assessor and conduit of new information. In practice, modifying projects in response to new information is a flexible, collaborative effort rather than a rigid process with many required boxes to check. Project teams can involve RECOVER (or not) in their work to incorporate new information into approved plans, and RECOVER can choose to become involved if deemed appropriate. Many decisions to modify an authorized project can be made by CERP leadership at the USACE Jacksonville District and the South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD). However, depending on the level of change necessary, additional analysis, review, reporting, and approvals by the USACE Division or Headquarters may be required by USACE policy.

NOTE: Some of these items are critical steps for the development of an adaptive management plan (i.e., #4, #6), but others address the evaluation of project alternatives.

SOURCE: RECOVER, 2022a.

SOURCE: RECOVER, 2022a.

Program-Level Adaptive Management Guidance

Although the Adaptive Management Integration Guide (RECOVER, 2011) encompasses program-level as well as project-level adaptive management, it provides more extensive guidance at the project level, especially for planning, which was the primary CERP activity when it was developed. The detailed description of how to implement the vision for program-level adaptive management (Figure 5-2) is provided in a Program-Level Adaptive Management Plan (RECOVER, 2015a), which follows the same framework as the Adaptive Management Integration Guide (RECOVER, 2011), identifying programmatic uncertainties facing multiple projects and strategies to address them, as well as the responsibilities of various parties. The Program-Level Adaptive Management Plan was reviewed favorably by the committee in NASEM (2016), although the committee noted that it was ambitious and lacked an implementation plan to ensure that appropriate actions were taken to support program-level adaptive management. (See below for a detailed discussion of the Program-Level Adaptive Management Plan.)

EVALUATION OF CERP ADAPTIVE MANAGEMENT AND INCORPORATING NEW INFORMATION INTO CERP DECISION MAKING

New information relevant to the CERP can come at any time, from many sources, and in many forms—from project-level monitoring, system-level monitoring, new science, new modeling, Indigenous Knowledge, and endangered species consultations to name a few. Although the term adaptive management is often used to apply to projects only when they are fully operational, the CERP adaptive management guidance and USACE processes provide the means to accomplish the broader goal of incorporating new information at all stages of program and project activities. During the planning process, new information is actively sought in the development of project plans, and RECOVER has been effective in supporting the creation of sound project-level adaptive management plans. In the process, RECOVER develops collaborative relationships with the Project Delivery Teams, which serve the CERP program well by providing a foundation for RECOVER’s later involvement if project teams encounter challenges in design, construction, and operation related to new information.

For post-authorization project design, construction, and operations, the overall adaptive management strategy (Figure 5-2) and the guidance built upon it (RECOVER, 2011, 2015a, 2022a-n; USACE and SFWMD, 2018) are sufficiently sound conceptually and detailed to accomplish effective adaptive management. The guidance exhibits most of the features of effective adaptive management described previously in this chapter—modeling of the managed system, a range of management choices, monitoring and evaluation of outcomes, mechanisms

for incorporating learning into future decisions, and a collaborative process for stakeholder participation and learning. Adaptive management, as implemented by the USACE, however, is not by nature a nimble process. Existing procedure requires that once a PIR is approved by USACE headquarters and authorized by Congress, it becomes subject to additional administrative requirements, which can make it burdensome and difficult to incorporate new information necessary to improve projects. Refinement of operations or project design may require new National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) evaluation and USACE reports with approval levels from District commander to headquarters to Congress, depending on the level of project change, its potential impacts, and effects on overall project costs (Table 5-1). These requirements are put in place to provide oversight of changes to a congressionally approved project, but they challenge timely and effective implementation of adaptive management and incorporation of new information. If “minor changes in design and costs from authorizing reports” are involved, changes can be authorized via an Engineering Documentation Report (EDR; USACE, 2000). If “reformulation of plans or other sufficient major revisions is required,” a Limited Reevaluation Report (LRR) or General Reevaluation Report (GRR) is required for approval (USACE, 1999). The LRR, employed when a reformulation of a specific portion of the project plan is proposed, can be approved at the USACE division level (i.e., South Atlantic Division), whereas the GRR, employed when a major reformulation of the plan is proposed, requires USACE headquarters approval. Both may require a new NEPA evaluation and an Endangered Species Act review. If project changes result in a 20 percent (or greater) increase in total authorized project costs (adjusted for inflation), a Post-Authorization Change Report (PACR) is required, which must be authorized by Congress, typically through WRDA legislation (USACE, 1999, 2000). Modifying projects during these stages usually requires negotiating changes to the Project Partnership Agreement,1 which is the legal agreement between the state and the USACE that outlines the terms and conditions for project construction and cost sharing.

These required processes make it challenging to modify projects in a timely manner once they are authorized. The major issue with CERP adaptive management is not the plan but rather how effectively the plan can be implemented, especially when applied across many projects at once. The following sections review and evaluate how effective the adaptive management process and the incorporation of new information into decision making has been in the CERP during four stages: (1) project-level adaptation during design and construction, (2) project-level adaptive management (post-construction), (3) adaptation of operations, and (4) program-level adaptive management.

___________________

1 See https://www.usace.army.mil/Missions/Civil-Works/Project-Partnership-Agreements.

TABLE 5-1 USACE Mechanism for Incorporating Post-Authorization Changes into a Project

| Report | Description | Authority |

|---|---|---|

| Engineering Documentation Reports (EDR) | Prepared when there are minor changes in design and costs from the authorizing reports. The EDR may also be used in lieu of a GRR to document other information not included in a decision document when project reformulation is not required, and the changes are only technical changes. | District commandera |

| Limited Reevaluation Report (LRR) | If reformulation of plans or other sufficient major revisions is required during Preconstruction Engineering and Design (PED), then districts shall prepare a GRR or LRR. This study provides an evaluation of a specific portion of a plan under current policies, criteria, and guidelines, and may be limited to economics, environmental effects, or, in rare cases, project formulation. Limited Reevaluation Studies ordinarily should require only modest resources and documentation. If any part of the reevaluation will be complex or will require substantial resources, or if the recommended plan will change in any way, a General Reevaluation is required. When a project must be reformulated or estimated costs updated, an Engineering Appendix shall be prepared. | Division |

| General Reevaluation Report (GRR) | If reformulation of plans is required during PED, then districts shall prepare a GRR or LRR. General reevaluation studies frequently are similar to feasibility studies in scope and detail. This is reanalysis of a previously completed study using current planning criteria and policies, which is required due to changed conditions and/or assumptions. The results may affirm the previous plan, reformulate and modify the plan, as appropriate, or find that no plan is currently justified. When a project must be reformulated or estimated costs updated, an Engineering Appendix shall be prepared. | Headquarters |

| Post-Authorization Change Report (PACR) | Section 902 of the WRDA of 1986, as amended, legislates a maximum total project cost. Projects to which this limitation applies, and for which increases in costs exceed the limitations established by Section 902, as amended, will require further authorization by Congress raising the maximum cost established for the project. The maximum project cost allowed by Section 902 includes the authorized cost (adjusted for inflation); the current cost of any studies, modifications, and actions authorized by the WRDA of 1986 or any later law; and 20 percent of the authorized cost (without adjustment for inflation). | Congressional authorization |

NOTES: Changes to an authorized project or operations plan may require NEPA documentation. “The scope and nature of the changes in the environmental effects of the project identified as a result of acquisition of new information, of changed conditions, or changes in the project will determine the appropriate type of NEPA documentation. Options include an Environmental Assessment which may result in a Finding of No Significant Impact or a Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement” (USACE, 2000).

a Project cost estimates are approved at the district level, unless the cost increase exceeds the project Section 902 limits, which then requires project reauthorization and the preparation of a PACR.

SOURCES: Information from USACE, 1999, 2000.

Project-Level Adaptation During Design and Construction

In this section, the committee examines two projects in which attempts to modify projects post-authorization based on new information during design or construction have been made: Picayune Strand and the Central Everglades Planning Project (CEPP). These case studies are intended to highlight processes that work well and issues that could impact restoration progress.

Picayune Strand

Construction at the Picayune Strand Restoration Project has occurred in phases, moving from east to west. The first construction component (plugging the easternmost canal) was completed in 2007, and as of 2024 construction is focused on the western portion (see Chapter 2: Picayune Strand Restoration Project). Over this time period, modeling tools and scientific understanding have advanced, offering new information about species and system response that could improve the original authorized project plan. Two major post-authorization modifications, based on new information that arose during design and construction, are discussed in this section: (1) mitigation of project impacts to Florida manatees (Trichechus manatus latirostris), a subpopulation of the West Indian Manatee, and (2) potential project alterations to reduce harm to endangered red-cockaded woodpeckers (Dryobates borealis).

Manatee mitigation.

Early assessments of the Picayune Strand Restoration Project during development of the PIR (USACE and SFWMD, 2004) noted uncertainties about downstream flow impacts to cold weather refugium for the Florida manatee, which is protected by the Endangered Species Act and the Marine Mammal Protection Act:

large numbers of manatees aggregate in the Port of the Islands marina basin in winter . . . in the deepest parts of the (dredged) marina basin. The recommended project will not affect this basin, and is not expected to adversely affect manatee aggregation in winter, but it will affect flows over the weir. . . . It is unknown what role the dynamics of freshwater inflow at the weir play in the balance of marina water temperature or basin stratification.

The PIR stated that the CERP agencies would continue to consult with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) and that an additional source of groundwater would be added in the vicinity of the Faka Union Canal weir if needed to maintain warm water refugia (USACE and SFWMD, 2004). However, no adaptive management plan was included in the 2004 PIR, because it preceded the USACE requirement for project-level adaptive management plans in the CERP.

A manatee mitigation element was later determined to be needed after a U.S. Geological Survey study concluded that canal plugging would reduce post-project discharge flows compared to the pre-construction condition, impacting existing manatee refugia in the marina basin (Stith et al., 2011). The Manatee Mitigation Feature was designed to create a new area with deep pools that provide a connection to warmer groundwater as refugia for manatees in winter months. The feature, along with other project design modifications, was included in an LRR (USACE, 2015), which required congressional reauthorization (obtained in WRDA 2016) because the total project modification costs exceeded 20 percent

of the authorized project costs. The LRR also included an adaptive management plan for the Picayune Strand Restoration Project. The modifications necessitated a revision of the Project Partnership Agreement between the USACE and the SFWMD, which was finalized in 2019 (USACE and SFWMD, 2019).

At its own financial risk, the SFWMD expedited construction prior to congressional approval to prevent further delays in overall project completion; construction was completed in 2016 (Figure 5-5). Manatee and water temperature monitoring has been conducted post-construction to assess the project performance, although the boat basin (the original refugia) is still providing warm water conditions. Once canal filling progresses to the point that the temperature of the original refugia falls below a 68°F threshold, the performance of the manatee mitigation feature can be formally assessed (H. Edwards, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, personal communication, 2024).

The overall adaptive management process from the time that a change in the project design was proposed through construction took approximately 5 years because of the willingness of the SFWMD to expedite the design and construction of the feature at its own financial risk. The potential impact to the manatee created strong regulatory and public interest to address the problem in

SOURCE: FWS, https://www.fws.gov/media/pup-manatee-mitigation.

a timely manner, and the SFWMD was able to move quickly to incorporate the new information and minimize delays on the overall project.

Red-cockaded woodpeckers.

The LRR that resulted in the addition of the Manatee Mitigation Feature also included a redesign of the Southwest Protection Feature (USACE, 2015). The project footprint was enlarged based on land easements required for this redesign to include a portion of the adjacent South Belle Meade tract to the west containing endangered red-cockaded woodpeckers, which do not occur within the original project area (Figure 2-9). Modeling associated with the redesign of the Southwest Protection Feature indicated that the project would create a flow-way through the area inhabited by red-cockaded woodpeckers, which would likely adversely affect them by increasing hydroperiods enough to convert much of the pine habitat they occupy to unsuitable wet prairie and marsh habitat (USACE, 2020c) (see Chapter 2 for further details).

Adverse anticipated impact on red-cockaded woodpecker habitat is a new issue that represents an unanticipated outcome of the project. It was not among the uncertainties identified in the Picayune Strand adaptive management plan created in the LRR just 4 years prior to its discovery (USACE, 2015). As with the manatee, modifications to prevent harmful effects on this endangered species are being evaluated in consultation with FWS, and RECOVER is not involved. In this case, unlike that of the manatee, the modifications involve no new features and are anticipated to result in very modest additional costs, no cost, or cost savings. Thus, this is an example of an action that can likely be approved administratively at the Jacksonville District level via an EDR (see Table 5-1). However, more than 4 years have already elapsed in analysis of the alternatives and planning of the redesign, and the required NEPA compliance review still lies ahead. How long the process takes, and whether it delays the completion of the Picayune Strand Restoration Project, will be instructive with respect to the speed at which projects can be modified in response to new information post-PIR. This example also illustrates the capacity to modify CERP projects when threatened and endangered species are involved as well as the time required by analysis and redesign.

CEPP

The CEPP is an example where multiple modifications have been proposed, and the challenges and successes provide several lessons for project-level adaptive management. The opportunities for incorporating changes to CEPP design based on new information, however, differ from those for other CERP projects because an extra step—a Validation Report—is required between project authorization and the Project Partnership Agreement for each of the four components of the CEPP. This step was added by the USACE due to concerns that the more rapid USACE

planning and approval process first piloted with the CEPP (termed the 3×3×3 process) resulted in greater risk and uncertainty associated with project design for a project as large and complex as the CEPP. The Validation Report creates an added mechanism to obtain approval for some design changes to authorized projects based on new information prior to construction. In this section, the committee examines five modifications being considered or implemented—two for CEPP North, which does not yet have an approved Validation Report, and three for CEPP South, which does.

CEPP North vegetated hammocks.

Backfilling the Miami Canal is a central component of CEPP North. The CEPP PIR recommended the addition of “upland landscape (constructed tree islands) approximately every mile along the entire reach of the backfilled Miami canal section (S-8 to I-75) where historic ridges or tree islands once existed” (USACE and SFWMD, 2014). The PIR discussed options such as spoil mounds, vegetated mounds, and tree islands and recommended the involvement of scientific input in the design of these features. To fulfill the latter recommendation, RECOVER convened a workshop in July 2022 to investigate backfilling methods. One outcome was a recommendation to use tear-drop-shaped vegetated hammocks oriented in the direction of flow with peak elevations 2–3 feet above marsh grade, which was higher than the 1.5 feet mentioned in the PIR (RECOVER, 2022o; USACE and SFWMD, 2014). The latest science was used to develop this recommendation, including information from the Loxahatchee Impoundment Landscape Assessment (LILA), a field-based tree-island research project that has been operating for more than 20 years. As of May 2024, the Project Delivery Team was evaluating the RECOVER recommendations in the finalization of the CEPP North design.

Because new information was anticipated in the PIR and significant cost increases are not involved, the proposed modification can be adopted easily and quickly without additional reporting requirements. This case illustrates the value of identifying uncertainties and the need for additional scientific input to inform the project design in a PIR, which undoubtedly expedited the process to convene a RECOVER workshop and enhanced the willingness of the design team to consider its input. By identifying the uncertainties and the plan for additional scientific input, the project team built additional flexibility to incorporate design changes into the CEPP PIR, such that the refinements to the vegetated hammocks did not need additional approval.

CEPP North L-4 Canal.

The second CEPP North case—a proposed redesign of features associated with the L-4 Canal in the northwestern corner of Water Conservation Area (WCA)-3A—is more complicated. The original design consisted of degrading the L-4 levee and constructing a culvert (S-8A) within the Miami Canal (Figure 5-6a). Preliminary modeling associated with pre-construction engineer-

SOURCES: USACE and SFWMD, 2023c; A. Kahn, SFWMD, personal communication, 2024.

ing and design revealed that this design would not produce the desired volume and distribution of flow into northwestern WCA-3A (H. Jarvinen, SFWMD, personal communication, 2023). To meet the project objectives, several modifications of the L-4 conveyance and distribution features have been proposed, including altering the geometry of the levee degrade, constructing three culverts with associated spreader canals in the L-4 levee degrade, and converting the S-8A culvert to a spillway and connecting canal (Figure 5-6b).

Like the Miami Canal backfill, the performance of the L-4 features was identified as an uncertainty and discussed in the PIR (USACE and SFWMD, 2014), but unlike the Miami Canal backfill, the proposed design changes added entirely new structures that were not mentioned in the PIR. The addition of these structures led to staff concerns that the new design might need to be approved by USACE headquarters and potentially Congress. However, it was determined that USACE approval for the proposed changes could be incorporated as a component of the required Validation Report for CEPP North, which can be approved at the (South Atlantic) Division level. Producing the Validation Report and the NEPA analysis necessitated by the changes to the L-4 features is the responsibility of the Project Delivery Team and will not involve RECOVER.

The contrast between this case and the Miami Canal backfill case highlights the challenges associated with adding previously unmentioned features to a project in a timely manner subsequent to its original authorization (i.e., post-PIR), even when the issue involved is identified as an uncertainty in the PIR. Staff noted that amid uncertainty, identifying the potential design alternatives in the PIR can obviate the need for high-level USACE approvals of new structures. Inclusion of Validation Reports in the design phase for the CEPP will facilitate approval of these modifications.

CEPP South.

In contrast to CEPP North, CEPP South is further along in its implementation progress (see Chapter 2) and has an approved Validation Report. Changes occurring during the construction would necessitate additional USACE approval (Table 5-1) and may require renegotiation of the Project Partnership Agreement. CEPP South’s original design is challenged by new information developed from the Decomp Physical Model (DPM), a pilot project designed to evaluate uncertainties associated with canal backfilling and restoration of sheet flow within the central Everglades. The DPM produced several results relevant to the CEPP that were not anticipated in the initial CEPP adaptive management plan (see Box 5-1).

Based on these findings, the DPM team (Saunders et al., 2021) identified uncertainties meriting further study and recommended four new adaptive management strategies in CEPP South (see Box 5-2). A series of discussions about an earlier draft of the DPM findings led to a memorandum from RECOVER in August 2020 recommending adoption of the first three adaptive management

BOX 5-1

Decomp Physical Model

The DPM is a large-scale pilot project intended to address uncertainties associated with restoring sheet flow to the ridge and slough landscape and to improve understanding of the ecological benefits of different canal backfilling options that could accompany levee removal. The DPM experiment was conducted between L-67A and L-67C, in an area near the border of WCA-3A and WCA-3B known as the “the pocket” (Figure 5-7). The project components include 10 gated culverts on the L-67A Canal (referred to as S-152) and a 3,000-foot gap created in the L-67C levee with three backfill “treatments” in the adjacent canal.

The first 2-month flow experiment was initiated in November 2013 by opening the gated culverts on S-152. Flows through S-152 were initially restricted to November and December, but this period was gradually lengthened over the next 3 years. Beginning in 2017, year-round flows through S-152 were permitted provided that total phosphorus (TP) concentrations in the L-67A inflow waters did not exceed 10 ppb and that other stage constraints for surrounding basins and canals were met.

Analyses of observations from DPM have demonstrated that

- restored surface-water flows are not following historic ridge and slough flow paths;

- sustained flow velocities of 1.5 to 3 cm/s are needed to promote sediment transport and rebuild ridge-and-slough topography;

- the Active Marsh Improvement project demonstrated the ability of vegetation removal in remnant sloughs to redirect surface-water flows and increase spatial extent of elevated flow velocities needed for sediment redistribution from sloughs to ridges;

- extreme high flows (>3 cm/s) can result in localized, damaging phosphorus loading followed by cattail invasion, and excessively high flows (>5 cm/s) may trigger erosion and topographic flattening; and

- canal backfilling improves habitat quality, and canal fill composed of limestone may retain phosphorus and reduce phosphorus transport downstream.

SOURCES: Modified from Saunders and Newman, 2023. Inset map by International Mapping.

SOURCES: Saunders, 2020; Saunders and Newman, 2023; Sklar et al., 2021.

BOX 5-2

Major Uncertainties and Four Recommended Adaptive Management Strategies for CEPP South

A final draft of the following uncertainties and adaptive management recommendations for CEPP South were provided by the DPM team (Saunders et al., 2021).

Uncertainties

- Marsh degradation associated with point source discharges. Even with inflow TP concentrations below 10 μg/L, high TP loading can occur based on high flow velocities, leading to ecosystem disruptions such as cattail growth. “The extent to which increased sediment TP is driven by localized variation in surface water TP, velocity, or P loading or a combination of the two remains uncertain.” Uncertainties about the ability of spreader swales to reduce these effects were also identified.

- Reducing canal-to-marsh flow. Uncertainties were identified regarding the most effective strategies to reduce the mobilization of nutrients and sediments from the L-67C Canal into the marsh and regarding the effect of different levee removal strategies on water quality and flow patterns.

- Active Marsh Improvement (AMI) in the Blue Shanty Flow-way. Several uncertainties were identified regarding the appropriate scale and design of AMI for the CEPP and the effect of AMI on biogeochemical processes and food webs. Additional identified uncertainties related to the design of ditch backfilling efforts and the effects on invasive species and the ecological risks and benefits with increasing flow through the Blue Shanty Flow-way, compared to the S-333 structures.

- Effects of spoil mound removal on culvert inflows and water quality. “Although spoil mound removal has the potential to restore some marsh flow in WCA-3A and downstream (the Pocket of WCA-3B), the extent to which removal will reduce inflow water TP or increase discharge performance of the culverts is unknown. Also unknown are the potential benefits of reduced sediment mobilization in and around the L-67A canal.”

- Tree island responses to hydrologic changes associated with the Blue Shanty Flow-way. Several uncertainties were identified regarding the effect of changes in flow volumes, velocity, water levels, and nutrient loading in CEPP South on tree islands, including nutrient dynamics and uptake, and wildlife activity. Also uncertain is whether management strategies could increase recovery of degraded tree islands.

- Impacts of CEPP South on invertebrate and fish assemblages. Uncertainties were identified regarding the optimal flow rates to maximize faunal benefits while minimizing risks as well as effects of strategies such as AMI and levee degradation on fauna, invasive species, and food webs.

Recommended Active Adaptive Management Strategies

- Use two field tests, including an in situ flume and experimental spreader swale tests, to identify optimal phosphorus loading conditions and strategies to reduce damaging, extreme flow conditions downstream of the inflow culverts (S-631, S-632, S-633).

- “The testing and application of canal plugs or backfill designs to reduce canal-to-marsh flow and maximize marsh-to-marsh flow across the degraded L-67C levee. In this test, observations will focus on tracking the mobilization, transport, and accumulation of canal-derived, P-enriched sediments into marshes downstream.” Testing would be accompanied by large-scale hydrologic modeling to determine cost-effective design alternatives.

- “Implement active marsh improvement (AMI) to enhance restorative sheet-flow velocities and Ridge-and-Slough (R&S) functions within the BSFW [Big Shanty Flow-way].”

- “Remove spoil mounds along the western edge of the L-67A canal. The objective of this field test is to evaluate the extent to which ~2000-ft (~600 m) gaps along the canal edge and adjacent to S-63x culverts will increase marsh-to-marsh connectivity between WCA-3A and WCA-3B and improve inflow water quality through the S-63x culverts.”

SOURCE: Saunders et al., 2021.

strategies noted in Box 5-2 (RECOVER, 2020b). The examples below represent the progress made in CEPP South in response to the recommendations from the DPM team and RECOVER.

CEPP South active marsh improvement and spoil removal.

AMI involves vegetation removal to reconnect historic sloughs and to enhance sheet-flow and ridge- and-slough functions within the Blue Shanty Flow-way, and its effectiveness was documented in the DPM (see Box 5-1). AMI was recommended by both Saunders et al. (2021) and RECOVER (2020b) and addresses an uncertainty identified in the CEPP PIR (#73, USACE and SFWMD, 2014, Annex D). Spoil removal, as recommended by Saunders et al. (2021), involves removal of dredge spoils west of the L-67A Canal to increase marsh inflows and reduce phosphorus concentrations in the canal. Adding spoil removal to CEPP South reduces overall project costs, by providing additional fill material that can be used in other components of CEPP South, while potentially enhancing ecosystem benefits. Both modifications are proposed as active adaptive management projects that could improve the understanding of ecosystem dynamics and potentially inform future management decisions. These modifications were approved at the USACE District level and by SFWMD leadership, and the work is moving forward.

In these two examples, design changes were implemented relatively quickly, with less than 4 years between acquiring new information and implementing the changes. A rapid response was facilitated by the arrival of new information in the form of explicit recommendations for design modifications that were relatively low cost (or cost savings); a fairly high certainty of enhancing restoration outcomes; coverage by existing NEPA; and, in the AMI example, linkage to an uncertainty that had been identified in the PIR.

CEPP South L-67C Canal backfill.

Both Saunders et al. (2021) (see Box 5-2) and RECOVER (2020b) recommended an adaptive management approach, based on the DPM findings, to explore applications of plugs or backfilling in the L-67C Canal to reduce the mobilization of nutrient-enriched sediments into WCA-3B in order to prevent adverse ecosystem effects. As of June 2024, the CEPP Project Delivery Team was still assessing the hydrologic and biogeochemical outcomes of various hydrologic modeling scenarios for backfilling the L-67C Canal, and the committee has not reviewed these results. Even though the original purpose of the DPM, which began operations in 2013, was to investigate the ecosystem benefits of complete or partial canal backfilling, this uncertainty was not included in the CEPP adaptive management plan (USACE and SFWMD, 2014, Annex D), nor was canal backfilling included as a management option, in part because its projected costs are substantial. Therefore, any change in design that incorporates canal backfilling, if approved by CERP leadership, will have numerous USACE reporting and approval requirements, perhaps including development of an

LRR with the appropriate level of NEPA and Endangered Species Act analyses; if cost increases exceed 20 percent of original authorized costs across all CEPP components, congressional approval of the modification will be required (see Table 5-1). The ability to consider these changes in 2024 was made easier by contractual delays in other portions of the CEPP project, which delayed the L-67C levee removal contract by several years. If that project component had proceeded, the costs of subsequent canal plugging would increase substantially.

The process to consider this major modification is ongoing, but the time and effort required stand in sharp contrast to the two CEPP South modifications already made. Whereas the new information that drove those two modifications was obtained at the same time as the information driving this one, those two are finished, and this one is just beginning. Several factors likely contribute to the longer time frame of decision making, including that the uncertainty regarding canal backfill and potential management options were not included in the CEPP adaptive management plan, the large potential costs of this change, the potential to delay the implementation of other CEPP components, and the absence of a legal driver such as the Endangered Species Act. These factors highlight the challenges posed by the USACE process in making major changes to an authorized project. Because the change is not driven by a legal requirement, such as the Endangered Species Act, but instead by overall improvement of benefits (and the reduction of adverse impacts), the change may require CERP leadership to prioritize restoration outcomes over the pace of implementation. Executing this modification while continuing the rapid progress of the CEPP will test CERP adaptive management.

Overarching Assessment

At the project level, the objective of adaptation during construction and design generally appears to be to improve restoration outcomes consistent with the original project objectives or to address unforeseen issues in design (Table 5-2). In the two examples from Picayune Strand, expected outcomes were modified to accommodate the needs of endangered species.

CEPP cases illustrate variation in the ease and speed with which projects can be modified based on receipt of new information during post-authorization design and construction. The CERP adaptive management process provides guidance for addressing issues that are included in a project’s adaptive management plan. Addressing unanticipated issues or those not included in the initial PIR and adaptive management plan can be more challenging, particularly if the project cost is substantially affected and the primary outcome is an improvement in restoration benefits (rather than a legal constraint such as the Endangered Species Act or the Savings Clause). The administrative level of

TABLE 5-2 CERP Project-Level Adaptation During Design and Construction or Project-Level Adaptation After Operations Begin

| Case Study | Timing of Change | Major Drivers | Issue Identified in Project AM Plan? | Approx. Cost of Change | Key Lessons Learned |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BBCW: Deering Estate | After operation | Correct project performance issues | No | Low | Even simple changes can take many years if a culture of AM, clear processes, and a sense of urgency are not in place. |

| Picayune Strand: Manatee Mitigation | During design and construction | Endangered Species Act | No | Moderate | Clear capacity to make major design changes when listed species involved. |

| USACE process for major changes time consuming; SFWMD expedited construction to limit impacts on project schedule. | |||||

| Picayune Strand: Red-cockaded Woodpeckers | During design and construction | Endangered Species Act | No | Cost savings to low cost | Clear capacity to make design and construction changes when listed species involved. |

| CEPP North: Vegetated Hammocks | During design and construction | Improve restoration outcomes to better meet project objectives | Yes | Low | Identifying uncertainties and building flexibility into PIR eases process of incorporating new information. |

| CEPP North: L-4 Canal | During design and construction | Correct project performance issues | No | Moderate | Identifying potential design alternatives in PIR would obviate need for high-level USACE approval of new structures. |

| CEPP South: Active Marsh Improvement and Spoil Mound Removal | During design and construction | Improve restoration outcomes to better meet project objectives | Yes | Cost savings to low cost | Willingness to make minor change when cost savings involved. |

| CEPP South: L-67C Canal Backfill | During design and construction | Improve restoration outcomes to better meet project objectives | No | Moderate to high | Lessons limited because early in process of potential change. Lack of inclusion of potential adaptive management strategy in AM plan complicates major change without ESA driver. |

NOTES: AM = adaptive management. Costs categorized as low (<$5 million), moderate ($5–20 million), and high (>$20 million) in 2024 dollars.

approval required depends on the magnitude of the proposed modifications and associated costs (Table 5-1). Minor changes can be handled as project redesigns at the district level. More complex and costly decisions require an LRR or GRR, likely triggering additional NEPA and Endangered Species Act analyses, reauthorization by Congress if cost increases exceed 20 percent, and potential renegotiation of the project partnership agreement. As the pace of CERP implementation has quickened under the large budget increases of recent years (see Chapter 2), incorporating important new information into the process can be challenging, because such information requires new analysis and potentially implementation delays while the resulting modification is under consideration. Unless the process can become more nimble, CERP leaders may have to weigh the costs and benefits of modifying a project to improve the restoration outcomes against implementation delays and the increased risk to achieving project objectives.

Difficulties experienced in incorporating new information at the design and construction stages foreshadow difficulties in implementing adaptive management across many operating projects and weaknesses in the implementation of the current adaptive management strategy. Although checks on design changes are appropriate to ensure sound analysis and decision making, the process may include oversight that is excessive for the changes proposed, and there may be ways to alter the process to make it easier to incorporate new information. For example, CERP teams have learned that building flexibility into the PIR (e.g., RECOVER input on Miami Canal plugs) can facilitate incorporation of new information with less burdensome reporting and approval requirements. Not including potentially necessary modifications in an adaptive management plan (e.g., canal plugs in CEPP South) can greatly increase the amount of time and the levels of administrative review needed to effect such a change, delaying restoration benefits (and allowing continued ecosystem decline) or potentially even foreclosing potential actions.

Project-Level Adaptive Management After Operations Begin

To date, there are relatively few examples of changes being made after a CERP project is constructed and fully operational. Broadly, changes can be triggered in two ways under project-level adaptive management. First, system responses to a project’s operation may trigger one or more elements of the Management Options Matrix in that project’s adaptive management plan. To the committee’s knowledge, this scenario has not yet occurred. Second, outside of those anticipated ecosystem response scenarios, other observed project or system responses or research can result in new information that suggests potential changes to a project. An example of the latter is the Deering Estates Flow-way in the Biscayne Bay Coastal Wetlands Project.

Examples of Project Changes After Operations Begin

Deering Estate.

Shortly after construction of the Deering Estate Flow-way was completed in 2012, concerns were raised about the effectiveness of short-term, nighttime 100-cfs pumping at the S-700 structure. Staff observed that when the pumps were turned on, the water levels in the freshwater wetland were elevated to the target ranges, but when the pumps were turned off during the day, the stages quickly decreased to pre-pumping levels (Charkhian and Niemeyer, 2023) as shown in Figure 5-8. Therefore, the project did not provide

SOURCE: Charkhian and Niemeyer, 2023.

the intended natural wetland hydroperiods. The adaptive management plan did not anticipate this outcome and therefore could not be relied upon for rapid implementation of an alternative management action. In water years (WY) 2015–2017, the SFWMD conducted a series of two wet and two dry season experiments comparing pulse releases to continuous pumping at different rates (Charkhian and Niemeyer, 2023). In June 2017, the SFWMD recommended switching to continuous pumping at 25 cfs, with the lower rate to account for increased operating costs. RECOVER reinforced this recommendation in a July 2017 memo (RECOVER, 2017). After undergoing additional approval processes, the changes were approved by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection in February 2018 and implemented in WY 2019. The time to effect this simple change—from identification of the problem, to analysis of alternatives, to permitting, to final implementation—was 6 years, even with long-term continuity among key staff. At the time, RECOVER had not finalized its SOPs for coordination with projects so whether the process would be completed in less time today is unclear.

Overarching Assessment of Project-Level Adaptive Management

As described earlier in this chapter, project-level adaptive management guidance has been well established, and most projects now include thoughtfully developed adaptive management plans. However, there are limited examples of project-level adaptive management and changes in response to new information after operations have begun (Table 5-2), and the CERP agencies seem challenged to develop timely solutions. This process inherently requires time to analyze the data and potentially design and conduct experiments to tease apart the factors affecting the response (or lack of response). However, because taking actions in the Everglades frequently involves multiple entities and agencies that operate at multiple levels and are governed by multiple laws and regulations, the most pernicious delays appear to be bureaucratic. A culture and clear processes to quickly and effectively transmit, review, and administratively act upon information have not yet been established within the CERP program. Although some changes will involve new engineering design and construction that understandably take time to implement, the Deering Estate example involved a simple operational change and still required 6 years to resolve the issue.

NASEM (2018, 2021) identified several elements of successful application of project-level adaptive management, including tracking of outcomes relative to project objectives and expectations, routine analysis and interpretation of data across long-term trends, and multi-agency data analysis and reporting mechanisms regarding restoration progress for each of the CERP projects. Although several CERP project components are operating, implementation of these routine

project-level adaptive management activities has not yet become well established. NASEM (2021) stated that “limitations in monitoring, analysis, and communication of results have impeded quantitative assessment and communication of restoration benefits”—a finding that remains relevant today. Addressing these gaps will enhance the success of adaptive management implementation and inform decisions that can improve restoration outcomes. For example, the C-111 Spreader Canal Western project has been operating since 2012 but has no explicit project-level adaptive management plan and no public reporting mechanism to explain how the project’s performance compares to expectations or targets. The Deering Estate component of the Biscayne Bay Coastal Wetlands Project has also been operating since 2012, but analysis of monitoring data is only provided in the SFWMD permit report published in the South Florida Environmental Report, which emphasizes data over the prior water year. Restoration outcomes relative to expectations, long-term trends, and other drivers are extremely difficult to determine from existing reporting, and single-agency reporting limits a full input from CERP partners about the project outcomes. To support adaptive management, the CERP needs to develop a periodic project-level reporting mechanism to communicate multi-agency assessments of restoration progress and implications for decision making.

Significant work has occurred to move the adaptive management program forward, but more work is needed to build a culture and expertise for CERP project-level assessment and reporting to ensure that projects are operating at their full potential and changes are implemented quickly. Such actions will provide confidence to Congress and the taxpayers who support the CERP that their investments are being well spent. Possible strategies for improving adaptive management are discussed later in the chapter.

Adapting Operations at Regional Scales

Adaptation in operations primarily occurs in three forms:

- operational flexibility, which uses the latest scientific information to make near-real time decisions within a pre-determined operations schedule;

- operational deviations, which respond to extreme conditions that necessitate operations that differ from the approved operations schedule; and

- periodic revisions to systems operations plans, to incorporate new information and new projects for improved regional water management.

Water managers have flexibility within system operations plans to make operational adjustments in light of changing conditions, and the leveraging of this flexibility to accommodate new information is a particular strength of

Everglades restoration and ecosystem management in recent years. Beginning in the 2010s, some agency staff began “weekly scientist calls” among various Tribal and governmental agencies to discuss recommended water management actions for the Everglades Restoration Transition Plan (USACE, 2011) relative to hydrologic and ecological conditions in WCA-3 (described in NASEM, 2021). These calls enabled scientists and managers to discuss the latest hydrologic and ecological monitoring data and condition assessments to inform water management decisions (i.e., opening or closing gates). These weekly scientist calls have continued through subsequent operational plans, such as the Combined Operational Plan (COP; see Chapter 2). Appendix C of the COP Biennial Report (USACE et al., 2023a) summarizes issues and recommendations from each call, with input from each participating agency, and each decision. These calls, if appropriately documented, represent opportunities for learning about the system response to improve future management. Recent system operating plans, such as the Lake Okeechobee System Operating Manual, have incorporated more flexibility than prior versions.

Extreme conditions, however, may necessitate deviations to approved operations plans, which must be approved by USACE Jacksonville District leadership, with appropriate levels of NEPA and Endangered Species Act assessments of the impacts of the deviation and coordination with affected parties. Emergency deviations were made in 2016 and 2017 under the incremental testing for the COP in light of high-water conditions. Deviations were also approved in 2023 and 2024 to allow more flow through the S-12s to reduce high-water conditions in WCA-3A that particularly impacted the Miccosukee Tribe (see Box 3-5). Despite the multiple requirements, these deviations can be made relatively quickly to respond to the emergency conditions.

System Operating Manuals require periodic updates to account for new information, new projects, and changing conditions. As noted in Chapter 4, the planned revision cycle for System Operating Manuals represents a useful means to incorporate new knowledge about climate change and lessons learned from recent operations, including extreme events. The committee’s last report (NASEM, 2023) and its review of the COP highlight the value of incorporating adaptive management in systems operations to encourage more structured learning. The adaptive management plan included in the COP Environmental Impact Statement (USACE, 2020a) describes a structured approach to learning with well-defined goals and targets, specific triggers, and resulting management actions for each specific uncertainty. Out of 18 total uncertainties, only 2 could be addressed in ways that could change COP operations without major procedural steps, such as NEPA assessment. However, by identifying these uncertainties, project teams could focus monitoring needs and structure data analysis around issues that could inform future System Operating Manual revisions (see Chapter 2: The Combined Operational Plan).

It is important to note the level of commitment in terms of staff time and resources required to incorporate new information into conditions-based decision making and adaptive management of operations. Experts and managers must devote time to regular meetings and associated data analysis and then additional time and resources to address the longer-term uncertainties identified in adaptive management plans. Clear communication, availability of appropriate monitoring data, and timely data analysis, synthesis, and documentation are all essential components of learning and adaptive management. Conditions-based operations may also require upgrades to some older structures to facilitate remote management of gates.

Overarching Assessment of Adapting Operations at Regional Scales in the CERP

Overall, the incorporation of new information in operations is a success story in the CERP. The use of periodic scientist calls has fostered communication between scientists and managers, applied current ecological and hydrological information, and facilitated improved and timely conditions-based operational decision making for the benefit of the ecosystem and the people that depend upon it. Not all regional operations are conditions-based, as described in Box 3-5, but this strategy has been applied successfully in the COP and Lake Okeechobee System Operating Manual. The process of learning from operations at the systems scale has proven valuable and should be continued in the next update to the COP—CEPP 1.0 (see Chapter 2).

Program-Level Adaptive Management

Program-level management involves the integrated coordination of system components to optimize ecosystem restoration benefits while balancing the need for flood control and water supply. Program-level adaptive management represents a structure to learn from new science, monitoring, and modeling to inform system-level decision making. RECOVER’s CERP Program-Level Adaptive Management Plan (RECOVER, 2015a) identified 13 “Priority 1 CERP programmatic uncertainties” that were designated “decision critical” and referred to as “showstoppers” (see Box 5-3). The Plan presented an adaptive management strategy to address these uncertainties and management option matrices, which described indicators used to assess performance, thresholds for when corrective action is needed, and actions that could be taken if restoration outcomes are not meeting performance targets. A key element of the Program-Level Adaptive Management Plan (RECOVER, 2015a) is the summary of the project-specific goals, interim goals from RECOVER (2005), “full restoration targets” based on RECOVER’s documentation of performance measures (RECOVER, 2007), and triggers for management action. However, for many of the identified uncertainties, the goals and targets have not been defined and are shown in the tables simply as “TBD” (to be determined).

BOX 5-3

Priority 1 Mission Critical Uncertainties Identified by the CERP Program-Level Adaptive Management Plan

Each uncertainty identified in the Program-Level Adaptive Management Plan (RECOVER, 2015a) was evaluated using three criteria:

- Knowledge: what is known about the uncertainty (high, medium, low) and how it should be addressed

- Relevance: what is the level of confidence (high, medium, low) that addressing the uncertainty will help improve the design or operation of CERP projects

- Risk: what is the risk (high, medium, low) that CERP goals won’t be met if the uncertainty is not addressed

Generally, those uncertainties with high risk, low knowledge, and high relevance were designated as Priority 1 CERP programmatic uncertainties—no further prioritization was conducted within the Priority 1 uncertainties. A total of 13 Priority 1 programmatic uncertainties were identified under topics such as storage capacity, climate change, project targets, and goals. The committee has not examined the rationale behind the identification of these uncertainties or evaluated the priorities established; they are listed here to illustrate a key development in adaptive management.

Storage

- Will enough storage be constructed to allow Lake Okeechobee water levels to be kept at ecologically beneficial levels, i.e., reduce extreme high and low periods?

- Will storage projects (e.g., Aquifer Storage and Recovery) provide enough storage to protect the estuarine resources in both dry and wet seasons?

Oysters

- What are the water quality (nutrients and suspended solids) impacts on larval oyster recruitment, given adequate numbers of spawning oysters in the estuaries (i.e., are larvae killed by poor water quality or are they washed downstream)?

Processes

- What is the role of flow velocities and flow volumes in maintaining characteristic ridge-and-slough patterns?

NASEM (2016) praised the RECOVER (2015a) Program-Level Adaptive Management Plan for asking highly relevant questions about many important systemwide issues affected by new information since the CERP was launched, such as storage, definition of goals, and climate change. NASEM (2016) also helped to outline some of the steps that should be taken (and when) to answer these questions and inform future decision making. The CERP programmatic adaptive management strategies identified to address the Priority 1 uncertainties included research, modeling, and synthesis, as

Design

- Which areas can be restored quickly (decadal) vs. slowly (century-millennia)? If areas are currently degrading, will waiting to start restoration extend the time of their recovery? Can ridge and slough patterns be reestablished simply by restoring hydrology?

- Is complete backfilling of canals and removal of levees necessary for restoration? Is partial or no backfilling of canals a viable alternative?

Water Quality

- How should restoration projects be designed to deliver increments of clean water to priority restoration areas, i.e., how best can water quantity and water quality goals be balanced to optimized restoration project performance?

Targets

- What water volumes and patterns of flow are required to restore submerged aquatic vegetation, oysters, and fish communities in the coastal Everglades?

- What are the hydrologic needs of the Everglades ecosystem (natural) compared to the human (urban and agricultural) systems? How much of this need is provided by CERP and how much more storage is needed?

Climate Change

- How will sea-level rise affect restoration efforts? How will sea-level rise affect coastal soils and the transition between brackish to oligohaline wetlands?

- What hydrologic/ecological/human changes could be affected by uncertain future demands for water for agriculture and urban users, as well as changes to the system due to climate change (changes in regional water balance) and sea-level rise?

- How will climate change affect the regional water balance? How will this affect the hydrologic assumptions used for CERP projects?

Balance Goals

- If the target lake stage in Lake Okeechobee is achieved, will the discharge problems to the Northern Estuaries be relieved? Which is more damaging to the estuaries, the volume and timing of Lake Okeechobee water releases or the nutrient loads in the water?

well as monitoring. NASEM (2016) noted that although the management options matrix was presented only for assessing monitoring results of “actual performance,” those thresholds could also be used to assess the results of forward-looking modeling analyses.

Since its publication, the Program-Level Adaptive Management Plan does not appear to have been used to organize or prioritize data analysis, modeling, or synthesis around the identified uncertainties to support decision making. In fact, the document is rarely mentioned by RECOVER or other CERP agency staff.

RECOVER’s attention has been consumed by its basic requirements and available resources (NASEM, 2021, 2023), and an implementation plan was never developed to address these important systemwide questions. The Everglades Science Plan recommended in NASEM (2023) could provide a mechanism to prioritize some of these larger questions, but so far, this recommendation has not been acted upon. Some progress has been made to address a few of the more localized uncertainties (e.g., the role of flow velocities and volumes in maintaining ridge-and-slough patterns), but, largely, the priority uncertainties remain valid and pressing today. The RECOVER 5-year System Status Report (e.g., RECOVER, 2014, 2019) is the primary vehicle to describe systemwide conditions. However, the previous committee’s report (NASEM, 2023) stated that the System Status Report “provides only a snapshot of current conditions, failing to provide a synoptic view of how or why the system is changing, why degradation is particularly problematic in specific locations, and what key management questions or knowledge gaps are proving to be obstacles.”

The ongoing analysis occurring as part of the Second Periodic CERP Update, which was recommended by NASEM (2016, 2018), may help address some of the pressing program-level questions regarding storage and sea-level rise. The Second Periodic CERP Update is expected to be completed in mid-2025 (Velez, 2024), and details about the ongoing effort are limited. NASEM (2016, 2018) recommended using the required Periodic CERP Update as a mid-course assessment of likely restoration outcomes relative to original expectations based on information gained since the last Periodic CERP Update in 2005. This new information relates to updated modeling tools, the feasibility of CERP storage, and climate change and sea-level rise.

In addition to the Periodic CERP Update, support for program-level adaptive management will necessitate attention toward other system-level issues, such as those identified in RECOVER (2015a) and any new priority uncertainties that may have emerged within the past 9 years. Dedicated agency resources and personnel are needed to address these program-level uncertainties and to build program-level adaptive management capacity. RECOVER funding and staffing have been cut substantially over the past decade, and additional dedicated resources may be necessary to make sufficient progress and ensure systemwide and forward-looking perspectives on these questions.

To support program-level adaptive management, the CERP should develop plans for periodic reporting on the extent of progress made toward restoration goals relative to expectations, whether thresholds for action have been crossed, and the implications of these findings for decision making. The System Status Report (RECOVER, 2014, 2019) provides an existing structure for such reporting; however, it tends to focus on recent trends and current status rather than ecosystem response in terms of expectations for restoration performance

and importance to meeting CERP objectives. Timely multi-agency reports or web-based dashboards with clear graphics that convey CERP progress in key metrics, summarize the overall conclusions, and indicate the trends in recovery are needed to communicate progress relative to restoration objectives. A good example of such reporting is the Chesapeake Progress dashboard,2 which includes an indicator of the trajectory of recent progress in the Chesapeake Bay Program and an assessment of whether the program is on course to meet each specific goal. A geographic information system-based dashboard would facilitate regional and systemwide analyses of project metrics and outcomes.

Overarching Assessment of Program-Level Adaptive Management in the CERP

Program-level adaptive management offers the potential to modify expected CERP outcomes as well as the objectives of individual projects based on new information and maximize the benefits of the restoration as a whole, but program-level adaptive management has yet to be implemented in a meaningful way. RECOVER (2015a) provided an important initial framework for program-level adaptive management, but until recently, little has been done to address system-level uncertainties. More attention is needed to understand evolving system-level risks, such as climate change (see Chapter 4), storage, and changing rates of ecosystem degradation, so that managers and scientists can assess their potential impacts on CERP goals and evaluate potential adaptations that may be needed at a program scale. The ongoing Second Periodic CERP Update is expected to provide useful information about program-level outcomes relative to original expectations and, ideally, will shape future discussions about whether additional program-level changes are needed to reach the desired restoration outcomes. Improved analysis and communication of systemwide restoration progress relative to expectations and targets is also needed to support program-level adaptive management.

REVISITING THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF ADAPTIVE MANAGEMENT

A well-functioning adaptive management program ensures that new information can inform decision making and improve restoration outcomes. However, building and supporting a functional program requires more than sound administrative guidance—it requires developing a culture and sufficient expertise in adaptive management within the CERP, a healthy and integrated science enterprise with adequate resources, effective and timely communication, and a nimble decision process that appropriately balances the level of oversight with the associated risks.

___________________

A Culture and Expertise in Adaptive Management

Building a culture that embraces adaptive management and the nimble use of new information in decision making is an essential but challenging step for large-scale restoration projects. Evidence-based CERP decisions are built on input from scientific and policy experts from multiple agencies and two Tribes, each having different histories, missions, approaches, protocols, and procedures for decision making that collectively define the culture of each organization. In addition, a myriad of nongovernmental stakeholders is engaged in the restoration effort in some capacity. Developing trust across groups within agencies, as well as across agencies, Tribes, and stakeholders, is a critical component of a culture of adaptive management. Staff have to trust that the data they are collecting and analyzing will be seriously considered, leadership has to trust that the vision they are providing will be implemented, and stakeholders have to trust that their input will be considered fairly and thoroughly. Therefore, the culture for adaptive management depends upon regular communication, transparency (including the sharing of information and data across agencies at multiple levels), and competence to execute. Building trust in the CERP science and decision process will provide the administrative and public support necessary for funding, decision making, and collaboration. See Box 5-4 as an example of the process for building trust in the use of adaptive management in the operations of the Glen Canyon Dam.

Building an effective community for adaptive management takes time and commitment to support the science and operational management collaboration needed by the decision agencies. Even with clear plans and guidance in place for adaptive management, it will not be effectively implemented without leadership commitment to the process across all levels of the CERP agencies and appropriately trained staff responsible for monitoring, analysis, synthesis, and communication. Adaptive management improves as personnel and the public become educated in the process of collaboration and learn to trust that the process will provide the framework for discussion and decision. Within the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, a regular multi-agency Adaptive Management Forum has helped to grow awareness and support for adaptive management, with meetings in 2019, 2021, and 2023. The Adaptive Management Forums were recommended by the Delta Science Plan, as well as the Delta Independent Science Board, as a way to engage local staff on current adaptive management issues and challenges. The forum highlights a commitment to using adaptive management throughout the agencies in the Delta and has helped to broaden adoption of adaptive management approaches throughout the region.

Regular adaptive management workshops in the Everglades could bring together thought leaders from other programs and institutions across the country (e.g., Trinity River Restoration Program, Platte River Recovery Implementation

BOX 5-4

Building an Adaptive Management Culture in the Glen Canyon