Incorporating Resilience into Transportation Networks (2024)

Chapter: 2 Build and Prepare the Resilience Team

PLAY 2

Build and Prepare the Resilience Team

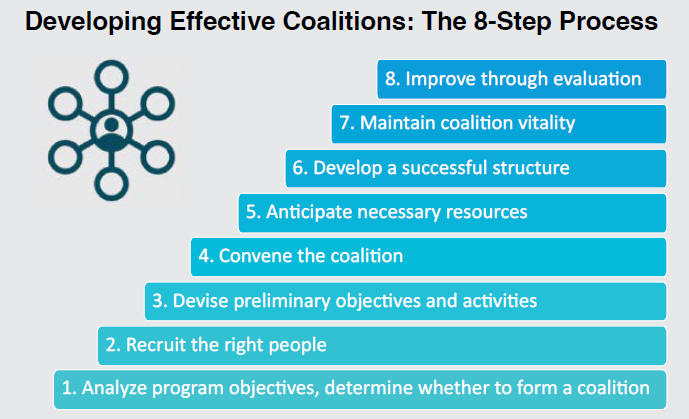

At the network level, resilience planning may require collaboration beyond what is necessary at the facility or system level. There are rarely instances where a single public agency can be effective by unilaterally evaluating and addressing only its part of the resilience ecosystem. As described in Play 1, a resilient network usually involves actors at various levels of the ecosystem acting in concert to prepare for, coordinate responses to, and recover from disruptive events. A resilience team can be formed within an existing group—such as a state or regional freight advisory committee, a standing MPO committee, an independent business group, or a special designation or jurisdiction—formed around network resilience. Figure 10 outlines eight steps for developing an effective resilience team. Figure 11 offers a self-assessment to help planners navigate forming and supporting a resilience team.

The composition and needs of the resilience ecosystem, as explored by the exercises in Play 1, can serve as a starting point. The self-assessment in Figure 11 can be applied when expanding the engagement or scope of an existing organization to serve as a resilience team or forming a new group or entity. Completing the self-assessment leads to an eight-point engagement plan for network resilience champions to create and articulate a clear vision of the purposes, payoffs, membership, duration, requirements, and concept of operations for a network resilience program or initiative.

Make the Most of Available Committees, Plans, and Programs

Most states and MPOs have formed freight advisory committees (FACs) to guide state or regional freight plan efforts. These groups often do not stray from that single mission. However, experiences such as the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic and the associated supply-chain crisis in 2021 and 2022 demonstrate the need for network collaboration to build resilience beyond formal state plans. In response to significant supply-chain bottlenecks and delays that COVID-19 created, states and several agencies of the federal government, including the White House, formed special committees or task forces to address supply-chain recovery issues. If properly scoped into their mission, standing advisory committees that include multiple public entities, as well as shippers and carriers, can be a forum to explore and define resilience roles.

An existing FAC or MPO committee on freight can use the self-assessment given in Figure 11 to consider expanding its scope to act as a network resilience team. This type of assessment can also be scoped as a task in a statewide or MPO-level long-range transportation plan (LRTP), a statewide freight plan, or a resilience plan associated with the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. In some cases, corridor coalitions or multi-state groups such as the Institute for Trade and Transportation Studies or the Mid-America Freight Coalition can undertake the assessment to explore tier potential to serve as a network resilience team. When launched in these contexts,

the assessment provides clear direction on (1) how and whether existing collaborative entities can serve (or be adapted to serve) as a network resilience team and (2) how a new coalition may be constructed to support network resilience requirements.

Assess the Authorities of Public Agency Partners

One way to explore commonalities between public and private sector roles in the transportation network resilience ecosystem is to dissect the supply chain into its physical and policy elements, as illustrated in Figure 12. The vulnerability considerations in the figure are questions a supply-chain manager (or shipper) is likely to ask regarding the design and execution of a supply chain. The checklist suggests areas of common interests and dialogue between public and private partners. The most likely public/private intersections for resilience planning are land use, modal investments, and last-mile access.

Local Agency Roles: Land-use and related policies regarding parking, utilities, transit, and law enforcement fall primarily to local and regional governments. These aspects are essential for determining warehouse locations, workforce accessibility (i.e., residential proximity to workplaces), street and curb access, and the operation of local streets and transportation services during disruptions. A report from the National Institute of Standards and Technology explains how communities can use risk-based land-use planning, which prioritizes investments in infrastructure projects in the safest areas, and thereby reduces risk exposures in hazard-prone regions.9 Similarly, RAND Corporation (2019) offers a methodology for incorporating resilience into long-range planning.10 Based on interviews and a review of relevant literature, the project team developed a logic model called AREA, which stands for absorptive capacity, restorative capacity, equitable access, and adaptive capacity, and puts forth a set of metrics related to different aspects of resilience. Other resources for incorporating risk and resilience in the planning process can be found in the literature review in Appendix A.

State DOT Roles: State DOTs often have ownership of highway infrastructure and other rights-of-way as well as control over federal and state dollars for investing in enhanced capabilities for disruptions. Many state and local approaches to making freight investment decisions are evolving. Monsreal et al. (2019) found that many states turn to FACs to assist with determinations of “the significance of the various freight projects.”11 The synthesis examined 31 state freight plans and surveyed freight planners to gather information.

Figure 12. Identifying network resilience partners and roles.

Agency staff working with existing committees or seeking to initiate new coalitions can benefit from consulting NCHRP Web-Only Document 293: Deploying Transportation Resilience Practices in State DOTs (Dorney et al. 2021) for guidance on federal policies supporting resilience efforts as well as overcoming internal organizational boundaries for resilience initiatives.12

Educate Partners About Key Resilience Concepts

For partners to meaningfully collaborate in a resilience initiative or program, there must be a shared understanding of what resilience is, how disruptions work, and how the actions of each partner relate to others. Because partners may not think about disruptions daily, it is difficult to establish standard nomenclature and a roadmap of what constitutes a resilient network. Even when training courses are offered, it often is difficult for members to retain and integrate resilience concepts into their everyday self-understanding or organizational culture. For this reason, collaboration can benefit from resources that:

- Create and share a common nomenclature and understanding of resilience concepts across partnering organizations.

- Relate these common concepts in a way that can be self-paced and requires 30 minutes or less in each sitting to fit into the limited schedules of agency staff and private managers.

- Is modular enough to allow team members to engage with material selectively when it is most relevant to the disruption or vulnerability being addressed at any given point in time.

- Provides a shareable resource that can form the basis for discussion in a group and serve as a reference for individuals to review key topics when they become relevant.

The Transportation Network Resilience Awareness Challenge is a resource that can both educate and engage diverse partners in network-wide resilience efforts. This resource is available through downloadable web links provided with this workbook and is fully documented in Appendix D.

Transportation Network Resilience Awareness Challenge Overview

The Transportation Network Resilience Awareness Challenge is an online workshop comprising three, 30-minute modules designed to engage transportation stakeholders on key topics related to network resilience. Each module includes the following:

- Begins with a brief introduction to the goals of the resilience challenge.

- Presents timely information about steps stakeholders can take to make transportation networks more resilient.

- Provides information about additional resources on resilience topics.

- Includes an end-of-module quiz designed to gauge stakeholder knowledge about actions to improve transportation network resilience within their job or organization as well as embedded questions to benchmark resilience efforts in their organization or profession.

- Asks participants to complete a brief follow-up survey and/or participate in a web-based focus group session.

The core content of the Transportation Network Resilience Awareness Challenge presents users with disaster/disruption scenarios using videos and graphics, followed by information about best practices and protocols that can be adopted to create more resilient transportation networks in the face of common threats. The modules

accompanying this playbook are interactive and flexible enough to be used by individuals or by facilitators in a small group setting. The modules cover three topics:

- Improving the resilience of transportation infrastructure.

- Improving cyber-security in support of transportation networks.

- Practices to support resilient supply chains.

The modules have been evaluated among public and private stakeholders at the national level and in three test regions: Atlanta, Georgia; Flagstaff, Arizona; and Illinois. Documentation of the testing process is available in Appendix E.2.

Target Audience

The Transportation Network Resilience Awareness Challenge is designed to initiate collaboration among the following:

- State and local transportation planning, policy, and engineering staff.

- State and local transportation operations staff (maintenance, permit, etc.).

- State and local planning partners and affiliate agency staff.

- Members of private sector advisory councils and committees.

- Members of the public.

Transportation agencies can customize the Transportation Network Resilience Awareness Challenge to be specific to any state, local, or regional transportation-planning environment based on the development process documented in Appendix D.1. This resource can be applied at the national or regional level, with Appendix D.2 providing illustrative examples of how it has been implemented both at the national level and with a regional MPO (Flagstaff, Arizona) during the wildfire disruptions of 2022. Transportation agencies can customize the Transportation Network Resilience Awareness Challenge to be specific to any state, local, or regional transportation-planning environment based on the development process documented in Appendix D.1. This resource can be applied at the national or regional level, with Appendix D.2 providing illustrative examples of how it has been implemented both at the national level and with a regional MPO (Flagstaff, Arizona) during the wildfire disruptions of 2022.

Whether applied in an FAC, MPO, statewide or regional freight plan, long-range plan, or corridor study, tools like the Transportation Network Resilience Awareness Challenge can help individuals explore common interests with planning partners and be a resource for smaller organizations.

Example: Managing Load-Weight Through National Emergencies

Transportation Network Resilience Awareness Challenge Supply Chain Module (video available at https://vimeo.com/showcase/10741790)

In the national testing of the Transportation Network Resilience Awareness Challenge, private firms sought to understand how their business interests could be advanced by engaging in the process. One of the case studies presented in the supply-chain module addressed this question by highlighting a memorandum of understanding (MOU) executed by state DOTs in the Mid-America Association of

State Transportation Officials (MAASTO). The MOU was created to address problems moving over-weight loads after the federal government declares a national emergency. A national emergency declaration permits state officials to allow overweight loads to travel on interstate highways if the carrier obtains a special permit from state authorities. However, the lack of uniformity regarding how much weight in excess of the standard 80,000 pounds individual states allow created an issue. After consulting with state bridge engineers, all MAASTO states agreed to allow loads up to 88,000 lbs. with a permit. Geno Koehler, permit chief for the Illinois DOT, called the MOU “a win-win for everyone.” The Transportation Network Resilience Awareness Challenge provides examples of how both public and private interests can benefit from a consistent understanding of concepts and requirements for handling disruptions.

Identify and Define Resilience Roles

Whether a resilience initiative occurs within an existing group or as part of a new coalition, success will depend on defining key roles for enhancing resilience. The self-assessment in Figure 11 and the guidance for identifying resilience partners and roles outlined in Figure 12 provide a high-level understanding of who should be part of the resilience team and their potential roles in a resilience initiative or program.

Supply-Side and Demand-Side Roles in Disruptions

The resilience of a network depends on both the supply of transportation infrastructure and services as well as the agility with which users can shift their demands on the system during a disruption. For example, changes to supply chains during the COVID-19 pandemic illustrate how profoundly sourcing and supply strategies can affect the effectiveness of transportation infrastructure (see NCHRP Web-Only Document 391, Volume 1, “Case Study 3B.1 Supply Chains in the Midwest Amidst COVID-19”).

Figure 13 is based on the information described in the Components of Resilience section in Play 1. The left-hand side of the figure lists the resilience objectives of actors using transportation infrastructure and services, while the right-hand side lists resilience strategies and indicators of actors providing transportation infrastructure and services. The figure demonstrates

how public and private sector resilience strategies rely on understanding the infrastructure and service options and requirements for any given tactic. For example, a DOT may understand from collaboration in a resilience team that access to a minimum number of warehousing locations can affect supply-chain resilience. This objective can affect the business case for an access point or interchange that may otherwise appear to be of limited utility in a normal prioritization process. Using Figure 13 as an example, a resilience team can identify critical business resilience needs and the corresponding transportation infrastructure and service conditions needed for success.

During a network disruption, the supply-demand relationship becomes highly interdependent. For example, shippers may change sourcing locations or modes during a disruption. When these shifts occur, business supply-chain management plans will directly affect the urgency and priority of highway, bridge, and port capacity efforts. In the same way, a public agency can let shippers and carriers know which bridges, ports, highways, or other facilities will most likely be preserved or restored quickly following a disruption scenario. This knowledge can inform the demands firms place on the disrupted network at different times during the disruption. Even with the most state-of-the-art supply-chain management systems, the availability of core transportation infrastructure and services is a crucial determinant of how firms leverage their internal resources. Likewise, no matter how intense DOT or port disruption recovery strategies are, strategic management of freight demands and service strategies can profoundly enhance recovery.

Team Roles and the Resilience Cycle

Defining resilience roles goes beyond understanding which teammates implement which actions. It is vital to define the timing of actions across the FEMA resilience cycle shown in Figure 14. The resilience cycle serves as a roadmap that indicates how and when resilience teams should define roles and their function to deal with a disruption. For example, opportunities exist to develop new modes, supply locations, access points, and other resources to improve risk readiness during the preparedness stage, but, when a disruption is imminent, operational and managerial activities must shift to the response phase and simultaneously start planning for recovery activities.

Account for Capability Maturity in Defining Resilience Roles and Needs

Each member of a network resilience team may have a different understanding of network resilience. This difference in readiness and sophistication is widely understood in terms of capability maturity.13 It is helpful for a network resilience team to self-assess (1) the key capabilities required of each entity in the resilience team based on the Components of Resilience from Play 1 and (2) the general level of maturity entities have with respect to these capabilities and how each entity can affect the network. Figure 15 outlines the criteria for capability maturity under the FHWA model, and Figure 16 shows how to structure a network-level capability maturity profile. For more information on assessing capability maturity, see NCHRP Research Report 970: Mainstreaming System Resilience Concepts into Transportation Agencies: A Guide (Dorney et al. 2021), which developed a series of checklists for assessing capability maturity for a wide range of resilience factors.14

Consider Private Sector Sensitivities

When developing capability maturity assessments for network partners, it is important to establish secure and appropriate indicators. Private sector partners may be reluctant to reveal specific weaknesses, but they can articulate their general needs and strengths without compromising strategic positioning.

While in-depth assessments of capability maturity at each transportation agency and supply-chain partner in a resilience network are beyond the reach of a network resilience team, assessing general capability maturity within a network resilience team serves the following essential purposes:

Leverage Comparative Strengths: The capability-maturity profile can highlight which entities in the resilience team are best equipped to manage different needs identified in the components of resilience. This can help define overall roles and reasonable expectations for roles during network disruptions.

Identify Capacity-Building Opportunities: The capability-maturity profile can highlight areas where members of the resilience team need further development, as well as which other members of the group may be able to assist. For example, in Figure 15, if the transit agency is at level 1 of capability maturity, but the local transportation/public works agency is at level 3, the public works agency could assist the transit agency in developing elements of its strategy. This could allow the transit agency to learn from the more mature network partner and ensure consistency with plans produced by other members of the network resilience team.

Target Strategies at Appropriate Levels: The capability-maturity model can help target resources where they will be most effective. For example, in the national pilot of the Transportation Network Resilience Awareness Challenge (documented in Appendix D.2), it was found that, while many seaports and private entities have advanced to a level of maturity beyond public sector agencies, they remain reliant on the public sector to understand and respond to their business needs.

Addressing Capability Maturity in the Transportation Network Resilience Awareness Challenge

The Transportation Network Resilience Awareness Challenge (Appendix D.2) revealed a disparity between resilience and the business-continuity programs at private firms, especially large multinational firms and public sector agencies. For example, companies like Walmart have been modeling supply-chain vulnerabilities from natural disasters and other disruptions for decades. During a Resilience Challenge focus group, a DOT emergency management official recalled a rockslide incident that closed both a highway segment and a parallel railway in the state. “The rail company’s response was laser-focused, resulting in rail line reopening weeks ahead of the highway.” It was also revealed that the private sector is cautious about discussing resilience issues in public forums because such a discussion may expose vulnerabilities. Taking a lessons-learned approach may be one way to overcome those concerns. The firm A.P. Moeller Maersk has been praised for its willingness to share lessons learned from a devastating cyberattack: “In the wake of NotPetya attacks, Maersk’s IT and security teams embraced transparency, greater collaboration with business, and a risk-based approach.”16

Build Inclusion and Social Equity into the Process

A key challenge facing a resilience team is the need to represent noninstitutional stakeholders. Institutions (public agencies and corporations) owning and operating the networks and facilities play a disproportionate role in determining outcomes in a disruption. However, these decisions can have far-reaching consequences after the disruption is over. Unlike most planning processes, urgent network disruptions may not allow for the types of deliberate and inclusive public engagement that are best practice for long-range planning efforts. Noninstitutional stakeholders can be drivers, mechanics, engineers, and consumers playing a critical role in the network with circumstances that go beyond what their employer would articulate. For this reason, it is incumbent on the resilience team to proactively find ways to include not only agencies and businesses but also the voices of the most affected stakeholders. This type of inclusion is essential to support the social equity objectives of resilience policy.

Social Equity in Resilience Planning

“In urban settings, neighborhoods with low socioeconomic status have some of the highest needs for climate adaptation and resilience-building efforts. Applying the concept of social equity to these efforts can help ensure that all communities are involved.”

Source: NOAA U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit. Social Equity | U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit

Achieving social equity in resilience planning requires agencies to go beyond just considering the distributive benefits and burdens of disruptions on different racial, income, and other classifications. Research demonstrates that diverse local stakeholders represent vital social capital, which can be a critical resource for addressing disruptions.17 Within communities, kinship linkages, neighborhood and family systems,

collective and verbal communication networks, and collective knowledge of the transportation market are all vital resources for enabling network strategies to be effective. Understanding the user dimension of resilience shown in Figure 10 is essential to building a resilience team. It cannot be presumed that business and institutional members of the resilience team will hold this knowledge or provide social equity perspectives on the intended benefits of a resilience strategy. When a resilience team identifies and recruits individuals within stakeholder groups that are not represented by businesses or institutions, the team opens pathways to new solutions not otherwise available.

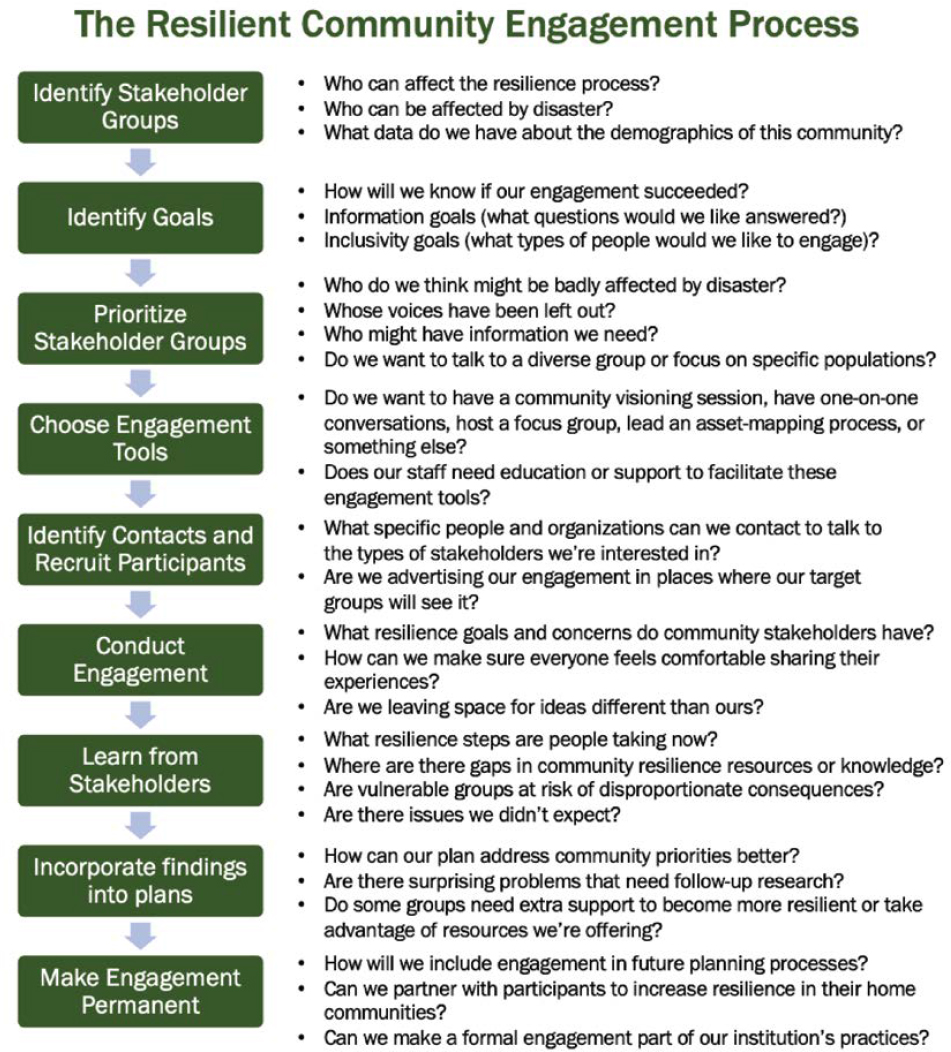

Recruiting and Including Noninstitutional Stakeholders from the Outset

When undertaking the initial steps of building the resilience team as shown in Figure 11. In Self-Assessment: Building a Resilience Team (Steps 1 and 2), the champions initiating a resilience team can define team objectives and recruit team members in a way that prioritizes community engagement. Figure 17 offers a practical guide for implementing a resilient community engagement process as part of the initial steps in building the resilience team. Much like the steps in Figure 11 and the processes described in the Economic Development and Planning Literature section of the literature review in Appendix A, this process can be undertaken within the scope of a DOT or MPO long-range transportation plan update, freight plan update, resilience plan, corridor study, or another initiative. The assessment can also be undertaken by a standing MPO or statewide FAC seeking to broaden its membership or scope to include resilience (see the Incorporating Risk and Resilience in Planning Processes section of the literature review in Appendix A for more details on processes for modeling resilience).

Following the steps shown in Figure 14 will provide a resilience team with (1) a clear set of social equity and inclusion objectives for the resilience team, (2) a clear roadmap of noninstitutional stakeholders and champions the team can enlist in resilience strategies, (3) a vision of how social equity in resilience planning relates to broader social equity objectives in related or supporting plans, and (4) inclusive criteria, sources, and candidates for noninstitutional community members who can represent these perspectives in the resilience team.

Engaging Communities in Place

Including noninstitutional stakeholders in resilience means going beyond issuing invitations to a meeting. Noninstitutional stakeholders may face barriers to participation in the resilience-planning process, including different levels of English-language ability, a need for meeting times to accommodate work schedules, a need to provide childcare, limited access to computers and online resources, a history of trauma with government officials, and long travel times to reach meetings at typical locations. Additionally, the insights noninstitutional stakeholders bring to the process might not speak directly to the technical models, databases, or operating plans typically found in institutional settings. For this reason, it is critical that team builders bridge barriers to participation—both in the way the team is structured and in the form input is acquired—and that the engagement process includes opportunities for involvement other than traditional meetings and communications. Figure 18 provides a range of techniques to ensure the process of building the resilience team supports more comprehensive social equity outcomes.

Resilience “In Their Own Words”

It is essential that noninstitutional stakeholders’ words are heard, used, and understood in resilience planning. It is easy for institutional partners to presume that their programs or

initiatives will meet the needs of nonrepresented groups simply by offering a service to a specific location or improving a particular indicator of performance. However, experience shows that the nuances of how stakeholders communicate about resilience can reveal critical areas of need and opportunities if articulated and interpreted inclusively. For example, there is a difference between the need for a mode of transportation from Point A to Point B and a mode of transportation enabling a worker to perform a key role in a disrupted supply chain, and then be home to attend to children early because of disrupted childcare. A resilience team needs to use the language of the affected population as much as possible in all stages of the resilience planning, response, and recovery process. A case study from Flagstaff, Arizona (fully documented in Appendix E) provides an example of real-time efforts to understand resilience needs in their own words during the wildfires of 2022.

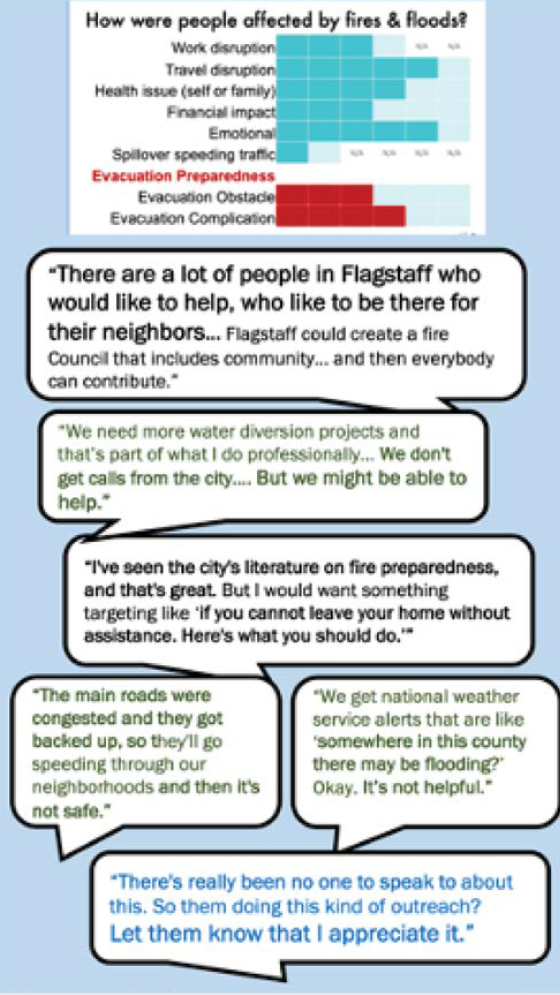

Case Study: Flagstaff Community Resilience Interviews—In Their Own Words

The Flagstaff Metropolitan Planning Organization (FMPO) wanted to understand the economic and social costs of road closures during the Pipeline and Tunnel wildfires in the summer of 2022 to identify actions that could prevent or reduce the adverse effects of travel disruptions during future wildfires and flooding.

Potentially vulnerable groups about whom FMPO had inadequate data were identified, including Navajo citizens and nondriving residents. With support from a qualitative research specialist, six community stakeholders from diverse backgrounds were interviewed via videoconference. They discussed how road closures due to the wildfires had affected them and reflected on how to make the community more resilient.

For the FMPO, the project “gave a very real face” to community needs and the effects of the FMPO’s decisions. It replaced the FMPO’s hunches about community needs with data. By identifying the unanticipated vulnerability of nondriving residents before it became a crisis, the project gave the FMPO more tools to plan for resiliency proactively. Additionally, the FMPO made connections with community stakeholders. All interview participants chose to be available for follow-up questions as the FMPO’s resiliency planning moves forward. Leads were identified to work with a local stormwater mitigation organization and to connect with Flagstaff’s homeless community, who live in the wildfire-vulnerable national forest.

Resilience Team Case Study: Louisiana Supply Chain Transportation Council

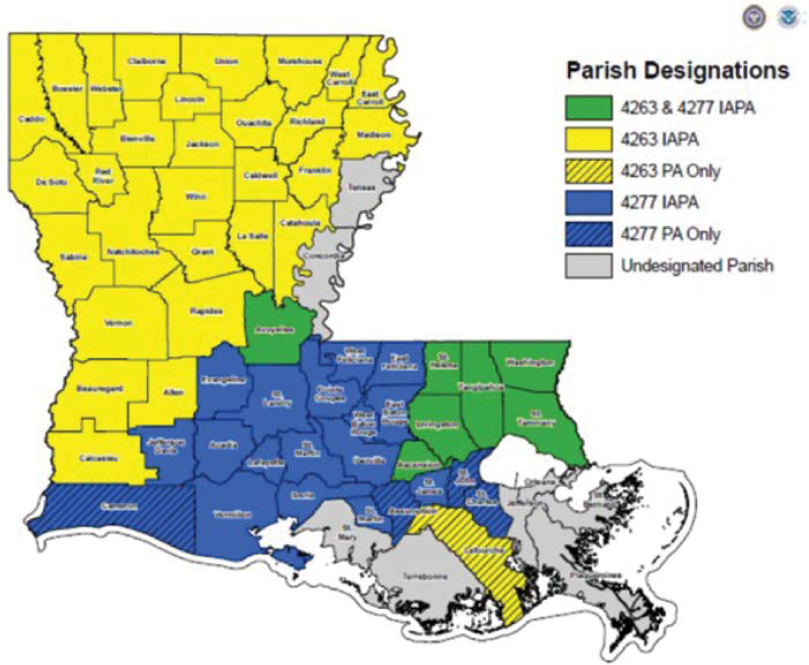

In 2016, Louisiana experienced two 1,000-year non-hurricane flood events in just 6 months (see Figure 19). Much of the state was declared a disaster area, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) activated the National Disaster Recovery Framework (NDRF).

A key component of implementing the NDRF in Louisiana was creating a public-private council that explored how to use Louisiana’s extensive multimodal transportation network to keep freight moving. In February 2017, federal and state agencies joined with the U.S. Chamber of Commerce to form Louisiana’s Supply Chain and Transportation Council (SCTC). The SCTC’s mission statement directs it to “increase the overall effectiveness of transportation and reduce impacts on commercial and agricultural interests from future events.”

PA: Public assistance; IAPA: Individual and public assistance.

Figure 19. Geographic extent of March and August 2016 floods.

State agencies provided the initial leadership and championing required for the council to gain traction via interest and participation. State agencies also provided resources such as meeting space, freight data, freight stakeholder relationships, and knowledge related to available programs and grants. The SCTC received further support from the Louisiana State Legislature, which passed Senate Concurrent Resolution 99 in May 2017 authorizing the council to make recommendations for improving the resilience of the state’s multimodal freight transportation network. While the authorization was not required for the council to operate, it highlighted the state’s role as a champion and helped organizers enlist participation from private sector stakeholders.

Federal agencies provided the initial framework for the council under the NDRF and facilitated the meetings that produced the vision. Like the state agencies, they also provide support in the form of resources, data, and tools used to model infrastructure impacts from future storm surges.