Incorporating Resilience into Transportation Networks (2024)

Chapter: Appendix B: Framework Document and Policy Guidance

B.1 Introducing Policy Framework and Methods

Objective and Scope of Appendix B: Framework Document and Policy Guidance

The principal objectives of this appendix are to (1) provide details for agencies to structure and initiate resilience programs and (2) suggest practical steps and methods for implementing initiatives within such programs.

Getting Started with Resilience Planning: Initiating a resilience program begins with (1) identifying network resilience partners, (2) pinpointing program requirements, (3) targeting specific business processes, and (4) building capacity for resilience.

Practical Steps and Approaches: Practical steps and approaches for resilience planning offered include (1) acquiring appropriate data and technologies, (2) following defensible procedures for plans, (3) considering successful outcomes, and (4) evaluating ongoing performance.

Integrating Elements of Resilience Planning: In practical terms, developing a resilience initiative is similar to following a recipe with multiple ingredients, a prescribed procedure, and a specification for the desired result.

The text box includes an analogy relating resilience planning to cooking and meal preparation. The first section addresses the principles and techniques shown in the text box. Subsequent sections address inputs (ingredients), procedures (recipes), and outcomes (dinner plan) for each of the five elements of a resilience program including the following:

- Frameworks

- Training and Capacity Building

- Organization Arrangements

- Analytical Tools

- Asset-Based Technique

Resilience Planning: A Cooking Analogy

There are four essential elements to cooking: salt, fat, acid, and heat. Knowing how these elements interact allows the chef to create any recipe, or dinner plan. The dinner plan in this sense is a reflection of context: what is the occasion, does it call for a particular type of food, and what do the guests like? Extending this analogy then, the guidance document helps the resilience manager understand the context for resiliency within their agency and planning environment.

B.2 Getting Started with Resilience Planning

Establishing a resilience initiative begins with a conceptual understanding of program elements in terms of (1) incorporating resilience, (2) engaging stakeholders, and (3) establishing context. Figure B.1 summarizes what each of these elements entails.

The following program elements inform the initial concept for a resilience initiative:

- Incorporating Resilience entails developing a vision, goals, objectives, and performance measures for the effort.

- Engaging Stakeholders entails identifying intended beneficiaries and actors in the initiative and their roles.

- Establishing Context entails considerations such as the agency business process, relevant partnerships and alliances, vulnerabilities to be addressed, junctures in the resilience cycle, and other pertinent factors.

Incorporating Resilience

The first element for developing a resilience program requires incorporating resilience into other existing programs and initiatives. Programs that resilience planning may be embedded within include established processes such as the state or MPO long-range transportation process (LRTP), programming and prioritization efforts (TIP or STIP), agency strategic planning processes, NEPA or corridor studies, and the work of standing MPO committees or FACs.

At the outset of a resilience initiative, it is advisable to consult these processes for opportunities to pinpoint and address resilience needs. Consulting these processes can ensure the resilient initiative is efficient and consistent.

Engaging Stakeholders

Engaging stakeholders in resilience planning involves coordination with private sector and community partners in ways different from traditional planning. In a network disruption, private firms such as shippers, carriers, warehousers, and retailers can determine network performance outcomes. Furthermore, environmental justice and social equity stakeholders have particular vulnerabilities related to disruptions that warrant explicit attention. For these reasons considering disruptions and vulnerabilities should (1) involve substantive dialogue with private businesses about operational needs and (2) be related to other stakeholder engagement processes in all aspects of planning.

Two critical resources guiding resilience stakeholder engagement are FHWA’s Vulnerability Assessment and Adaptation Framework, 3rd Edition,40 and National Disaster Recovery Framework,41 both of which address community engagement in a resilience program. Other federal, nonresilience-specific processes also create openings to engage stakeholders on resilience needs. Examples include FHWA’s Context Sensitive Solutions Framework (CSS), FHWA’s Community Impact Assessment,42 and FHWA’s Transportation Performance Management Framework.43

Stakeholder Engagement Links

https://www.fema.gov/emergency-managers/national-preparedness/frameworks/recovery.

Linking Community Visioning and Highway Capacity Planning, TRB.

A Guide to Transportation Decision Making, FHWA.

Going the Distance Together: Context Sensitive Solutions for Better Transportation, FHWA.

Public Involvement/Public Participation, FHWA.

Going the Distance Together: A Citizen’s Guide to Context Sensitive Solutions, TRB.

Guidance on State Freight Plans and State Freight Advisory Committees, FHWA.

Building Planning Capacity Between Public and Private Sector Partners in the Freight Industry: A Resource Manual for Public and Private Freight Planning Interests, NARC and FHWA.

https://fhwaapps.fhwa.dot.gov/planworks/Application/Show/4, FHWA PlanWorks.

Establishing Context

Establishing the context of a resilience initiative can frame network requirements in ways that fully leverage available information and partnerships. Adequately assessing the resilience context ensures vital aspects of the resilience ecosystem are prepared for potential disruptions. Elements of context include the following:

- Agency Context

- Hazard Type Context

- Community Context

- Economic Context

- Infrastructure Context

The following guidance addresses the process for establishing these elements.

Agency Business Process Context

Whether an agency is implementing a new resilience program or updating an existing program there will likely be business process decisions to be made about how the resilience program fits within the agency’s existing workflows. It is also likely these decisions will affect their process relationships with external stakeholders. State DOTs are complex organizations, not only because of their size and function, but also because of their interrelationships with other federal, state, and local agencies, utility providers, lifeline service providers, and their role in supporting the natural environment and industry supply chains. Early in developing the resilience program, it is incumbent on the resilience manager to understand, to the extent possible, and consider how these complexities will affect the development and implementation of the resilience program. This report will discuss interagency relationships in the following contextual sections; however, it is reasonable for the resilience manager to begin thinking about how an agency’s business process may be affected by those relationships while considering how the program will fit within its workflows. Agency-specific business process issues to consider may include the following:

- Alignment with agency strategic direction.

- Integration of resilience program into existing workflows: transportation asset management, structures, long-range planning, corridor planning, project development, safety, emergency response, etc.

- Relationship between resilience process owner (often central office divisions) and implementing elements (district/region) of the agency.

- Funding priorities of resilience improvements and other agency priorities.

- Data needs and analytical requirements.

Hazard Type and Resilience Cycle Context

Initiating or updating a resilience program begins with a decision about the scope of the effort. Two important scope-related questions are event type(s) and which phase(s) of the resilience cycle are of concern to the agency, and its partners. These questions are not easy to answer because of the interrelated nature of the resilience process. A focus on one phase of the resilience cycle will likely affect potential outcomes in another phase as well as the plans and efforts of agencies responsible for other phases of the resilience cycle.

At the same time, an agency could ask itself whether it should take a more systemic perspective of resilience. For example, the New Zealand Transport Authority, in the development of their risk management program,44 posed the question of whether it is prudent to focus solely on specific types of events given the increasing uncertainty surrounding climate change—where uncertainty

makes it more difficult to estimate specific event risk probabilities. Rather than focus on specific types of events and classes of assets, should the agency focus on systemic resilience practices that consider multiple event types and the interdependency of asset types, in essence, improving system resilience across multiple categories: transportation and utility assets, lifeline services, economic/business continuity, and community resilience? Such an approach would almost certainly affect disaster response and recovery plans. This distinction can help articulate different approaches to incorporating resilience in transportation networks.

Hazard Identification: FEMA45 classifies hazards as either natural or anthropogenic, with anthropogenic broken down into intentional and unintentional. FEMA further categorizes events into atmospheric (metrological), geological (earth), hydrological (water), extraterrestrial, and biological, each of which can be broken down into specific event or hazard type. Figure B.2 shows FEMA’s generalized listing of hazard types, at-risk assets, and potential impacts.

U.S. DOT 46 distinguishes between planned disasters (biological, chemical, nuclear, and terrorist attacks) and natural disasters (earthquakes, fire, flood, hurricanes, thunderstorms, tornadoes, and winter storms). Of concern for development of a resilience program is that the strategic (for planned disasters), geographic, hydrological, and overall climate characteristics of a given area underlie decisions concerning resilience programs. As such, it is important to purposefully consider hazard types as this will help ensure a collective understanding of the scope of the effort.

Resilience Cycle Phase: Deciding which phase(s) of the resilience cycle to focus on is key. As shown in Figure B.3, there are four macro phases of the resilience cycle: preparedness (ongoing), response (short-term: days and weeks), medium-term recovery (weeks and months), and long-term recovery (months and years). Within these macro phases of response and recovery, there are additional phase classifications that can help an agency focus the efforts of their resilience program:

- Response: Emergency relief to address what has been impacted by the event.

- Recovery: Restored, repaired, replaced, and improved.

- Short-term: Restoration, return what has been damaged to a functioning state.

- Medium-term: Functionally, returned to predisaster levels or better.

- Long-term: Improve and further develop the infrastructure.

Figure B.2. FEMA list of hazards, assets at risk, and impacts.

It is worth noting that the resilience cycle is not necessarily a linear and sequential process even though certain steps within the cycle may be. Like most systems, there will likely be intermediate feedback loops and lessons learned (positive and negative) that can be fed back into the planning and preparedness phase of the cycle. In addition, the consequences of, and the full recovery from, a disruptive event can take years to be fully known and improvements implemented. For example, the funding for the improvements needed in the aftermath of the Howard Street Tunnel Fire was approved in 2020, almost 19 years after the event. With that being said, even if an agency decides to focus on a specific phase of the resilience cycle, it is important to understand the program’s relationship with other phases of the resilience cycle. These preliminary decisions also help direct data and information-gathering efforts as well as provide initial indications of which local, state, and federal government agencies to include.

Interagency Coordination: The stakeholder engagement process begins by asking internal subject matter experts (SMEs) to help with the development of a resilience program. Relevant disciplines could include long-range planning, asset management, structures, project development, environmental, programming, design, project delivery, operations, and maintenance. Essentially, all DOT disciplines can provide SMEs and help establish processes within their disciplines. Early involvement from internal stakeholders is essential to creating buy-in and will help with the implementation phase to assimilate new resilience program workflows. It is critical to engage agency leadership at each phase of the program development process to ensure buy-in, and if necessary, make course corrections, to avoid wasted effort. The soundness and implementation of a resilience program depend on buy-in from different internal functions and the agency leadership team.

Resilience Links

https://doi.org/10.17226/22702, NCHRP Report 732.

https://doi.org/10.17226/25463, NCHRP Report 39.

http://apps.trb.org/cmsfeed/TRBNetProjectDisplay.asp?ProjectID=3685, NCHRP Project 08-136 (126).

https://environment.transportation.org/center/products_programs/webinars/resilience.aspx, AASHTO.

https://environment.transportation.org/environmental_topics/infrastructure_resilience/, AASHTO.

https://environment.transportation.org/center/rsts/, AASHTO.

https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/sustainability/resilience/, FHWA.

https://www.fema.gov/emergency-managers/national-preparedness/climate-change, FEMA.

https://www.fema.gov/emergency-managers/national-preparedness, FEMA.

Community Context

This research effort is focused on incorporating resilience in transportation networks: planning for them, designing them, and constructing them. Community residents and businesses depend on and are served by their connections to larger regional, state, and national transportation networks; and transportation networks can be dependent on them as well. Therefore, it is important to understand this relationship and the interdependencies. FEMA uses the term whole community”47 to define how it views the role of the community in developing resilience programs. From a resilience perspective, community can be viewed broadly to include the provision of lifeline services like medical care and general community services to vulnerable populations, like assistance to the aging, food assistance, and mental health services. In the development of the resilience program, the resilience manager should not just focus on external definitions of community. The sources for such a definition are likely the community itself: how does it define community?

Community context is also about the human environment and social structure. It is where we live, work, play, and raise families. It is a sense of place that is inclusive of the built environment, the natural environment, and the services that support a community. Establishing a contextual understanding of community requires a focus on people, their connections to the broader community, an appreciation for how they live, and where they live. It requires purposeful attention to sub-groups within a population and how the transportation system serves and affects their lives. Agencies develop and establish a community-responsive resilience program by understanding who benefits from the program.

Understanding a community’s desired future will inform the planning and policy development of a resilience program. A community vision represents a common foundation for a variety of community plans, including land-use, transportation, and economic development plans. Using such a vision as input into transportation decision-making helps ensure that the decisions made in transportation planning and project development advance and support community values.

In a broad sense, this inquiry will help agencies understand community objectives and how these objectives might mesh with the objectives of a resilience program, discover what resources are available to assist in the program and plans, establish lines of communication, and determine which roles and responsibilities are necessary for the execution of resilience efforts.

Community and Transportation-Planning Links

Scenario Planning Guidebook, FHWA.

Supporting Performance-Based Planning and Programming Through Scenario Planning, FHWA.

Linking Community Visioning and Transportation Planning, TRB.

Environmental Justice, FHWA.

Historic Preservation, FHWA.

Resource Center - Civil Rights Team, FHWA.

Transportation Equity-Planning Process Briefing Book, FHWA.

https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/livability/cia/quick_reference/index.cfm, FHWA.

https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/planning/performance_based_planning/pbpp_guidebook/, FHWA.

Economic Context

The efficient movement of goods and services is essential to the economic competitiveness and vitality of communities and regions. This is especially true after a disruptive event. Because freight movement is conducted by the private sector, it is critical to engage carriers, shippers, and other businesses in the resilience planning and decision-making process. Collaborating with freight carriers and practitioners can ensure that private sector supply-chain considerations are part of an overall resilience program. Conversely, private sector entities need to understand the roles and responsibilities of all public sector agencies, so they can develop comprehensive mitigation and response plans and establish critical lines of communication. Additionally, collaboration and coordination with federal, state, local, and regional agency practitioners are important since freight crosses jurisdictional lines. A broad set of freight stakeholders could include last-mile and mid-stream carriers, railroads, economic development organizations, chambers of commerce, ports, and commodity associations—some of which may already be represented on state DOT FACs.

In addition to considering goods movement, an agency might also consider the movement of people in a post-disruptive event situation. A resilience manager might consider access to jobs, especially for essential workers, as well as access to daily services and lifeline services. The rate at which businesses and public agencies can resume operations after a disruption is an important consideration in any resilience program.

Freight Planning Links

Freight and Land Use Handbook, FHWA.

Freight Performance Measurement, FHWA.

Freight Planning, FHWA.

Guidance on State Freight Plans and State Freight Advisory Committees, FHWA.

Building Planning Capacity Between Public and Private Sector Partners in the Freight Industry: A Resource Manual for Public and Private Freight Planning Interests, NARC and FHWA.

Institutional Arrangements for Freight Systems, NCHRP.

Integrating Freight Considerations into the Highway Capacity Planning Process: Practitioner’s Guide, TRB SHRP2.

Integrating Freight in the Transportation Planning Process, NHI.

Infrastructure Context

In addition to understanding transportation network needs (capacity, preservation, hardening, and operations), it is important for a state DOT to understand the interdependencies between utility and transportation infrastructure. Interagency coordination and collaboration are crucial success factors, and a comprehensive understanding of these interdependencies will serve all stakeholders in the development of their respective risk and resilience programs, regardless of which hazardous event or phase of the resilience cycle an agency may be focused on. There are advantages to early coordination. It is in the process of establishing a resilience program that agencies have an opportunity to share the scope of their respective resilience efforts and establish lines of communication

and partnerships while clarifying each agency’s roles and responsibilities during disruptive events. Interagency partnerships can include representatives from local, state, regional, and federal agencies. An important element of any resilience program is the interface with the participating agency’s programs and practices. Like the intra-agency inquiry, interagency outreach is intended to build the knowledge base that will contribute to and inform the resilience effort.

Transportation Network Context: Establishing transportation context is an exercise in assessing the SWOT associated with the transportation network and its interdependent elements. Such an assessment might examine the following:

- Data and analytic needs.

- Existing and projected capacity constraints.

- An assessment of the system’s redundancy and grid spacing as well as its multimodal freight and passenger characteristics.

- The condition of individual assets and the aggregate network.

- The operational characteristics of the transportation network, including an assessment of an agency’s technological sophistication, signal optimization and control, and real-time user information systems.

At the same time, an agency should assess its transportation-planning processes, including long-range planning, corridor planning, safety, and operations planning efforts.

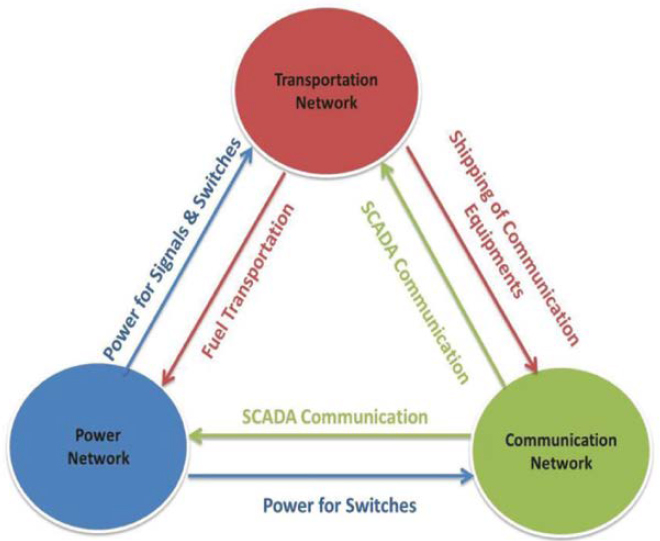

Utility Infrastructure Context: Utility infrastructure is critical to community health and cohesion. Utility infrastructure is not only susceptible to interruptions during events, but it may also be dependent on a functional and operational transportation system, see Figure B.4. Infrastructure and process interdependencies can occur at many different levels and areas, which highlights the complexity of systems-to-systems interactions. As such, it is important to include utility owners and operators as critical stakeholders. The importance of these considerations can be shown with an example from the NCHRP Web-Only Document 391, Volume 1, case research. The New Zealand Transport Agency 48 used the concept of interdependencies as a means of assessing the criticality

SCADA: Supervisory control and data acquisition.

Figure B.4. Infrastructure interdependencies.

of transportation network components and networks. The criticality assessment considered the number and type of utilities within the transportation facility right-of-way and whether there was a dependent relationship between the two infrastructure types; whether the transportation facility served lifeline services; and whether a utility had an interdependent relationship with the transportation facility. This is the type of consideration that could prove useful to a state DOT in its overall project prioritization process.

Infrastructure Links

Advancing Transportation Systems Management and Operations Through Scenario Planning, FHWA.

Planning for Transportation Systems Management and Operations within Corridors – A Desk Reference, FHWA.

TSMO Capability Maturity Frameworks, FHWA.

Transportation Safety Planning, FHWA.

https://fhwaapps.fhwa.dot.gov/planworks/Home, PlanWorks.

B.3 Practical Steps and Approaches

Practical steps and approaches to inform resilience initiatives include resources like the following:

- Frameworks

- Training and capacity building

- Organizational arrangements

- Analytical tools

- Asset-based risk management

Table B.1 provides examples that are available in NCHRP Web-Only Document 391, Volume 1. Each of these resources has been applied in different parts of the resilience/emergency management cycle.

Requirements for Implementing Practical Steps and Approaches

Using the resources shown in Table B.1 requires an agency’s awareness of available technologies, resources, and practices. The status of these requirements in any given agency can be informed by disruption experiences documented in NCHRP Web-Only Document 391, Volume 1, Section 2. Factors enabling successful use of the elements in Table B.1 include data collection, storage, security, and access; staff, expertise, roles, and responsibilities; and feedback, updates, and dissemination.

Data Collection, Storage, Security, and Access

Several case studies point out the importance of having and securing the right data for making decisions in a crisis. In terms of data collection, it is important to determine what data are most critical for decision-making and implementation of response and recovery strategies. Having good inventory data around critical facilities and networks and maintaining that data in multiple formats so that they can be accessed when a disruption occurs are critical to the ability to respond and recover effectively. The breadth and frequency of recent cybersecurity attacks, like NotPetya and Solar Winds, make this topic particularly relevant in today’s environment.

The 2017 NotPetya cyberattack took down the global computer network of Maersk, the world’s largest ocean shipping company. The Maersk experience is a poignant example of the importance of building in good resilience protocols and practices regarding data storage and cybersecurity. Within minutes of the NotPetya attack, all of Maersk’s domain servers that set the rules for network access had been wiped out. Had it not been for a power outage in Maersk’s Ghana office, which

Table B.1. Resources applied in the emergency management cycle.

| METHODS AND TOOLS | CASE STUDY | CASE STUDY # | CYCLE OF EMERGENCY MGMT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Framework | Puerto Rico Equity | 3B4 | Response |

| Florida DOT | 3A5 | Preparedness | |

| Louisiana Supply Chain | 3A6 | Preparedness | |

| Washington State DOT | 3A7 | Preparedness | |

| EPA Rhode Island | 3A4 | Recovery | |

| Howard St. Tunnel | 3B2 | Mitigation and Response | |

| Port of Everett | 3AB1 | Preparedness and Response | |

| Atlanta (ARC) Vulnerability and Resiliency | 3A1 | Preparedness | |

| Training and Exercise | Port of Everett | 3AB1 | Preparedness and Response |

| Super Storm Sandy | 3B5 | Response | |

| Washington State DOT | 3A7 | Preparedness | |

| Howard St. Tunnel | 3B2 | Response | |

| Modeling | Pedestrian Flow Path | 3A8 | Mitigation, Preparedness and Response |

| Typhoon Emergency Response | 3A9 | Response | |

| Super Storm Sandy | 3B5 | Response | |

| Climate Ready Boston | 3A2 | Mitigation and Preparedness | |

| Organizational | Asset-Based Risk Mgmt | 3A10 | Mitigation and Preparedness |

| Florida DOT | 3A5 | Preparedness | |

| COVID Supply Chain Midwest | 3B1 | Response | |

| Puerto Rico Hurricanes | 3B3 | Response | |

| Louisiana Supply Chain | 3A6 | Preparedness | |

| COVID Regional Response | 3AB3 | Response | |

| Risk-Based | Asset Based Risk Mgmt. | 3A10 | Mitigation Preparedness |

| Cyber/GPS Security | 3A3 | Preparedness and Response | |

| Climate Ready Boston | 3A2 | Mitigation and Preparedness | |

| EPA Rhode Island | 3A4 | Recovery |

saved a single domain server from the attack, the company would have had to create its entire global IT network from scratch. Because of the unaffected Ghana server, Maersk was able to rebuild its internal networks using the clean software from the single off-line computer. The company was able to resume largely normal operations in less than 2 weeks, and in just under 1 month of the attack, Maersk rebuilt nearly 50,000 computers to fully restore its network. In the wake of the attack, Maersk IT staff have shared several important steps to prevent and recover from cyber disruptions:

- There is no zero-risk cyber environment. Planning should be undertaken with the assumption that cyberattacks will be successful. It is necessary to understand cyber threats and keep an eye on internal activities, and act accordingly, in the case of any malicious activity.

- Prevention only is not an effective strategy. Automated detection and appropriate responses should be developed.

- Privileged access management (PAM) is extremely important for transactional networks. PAM manages all system accesses/restrictions within the existing active directory in a company. If Maersk had limited the number of privileged accounts, fewer machines would have been infected.

- Cyber insurance protection can help reduce incident remediation costs. It is estimated that the cyberattack on Maersk cost the company between $250 and $300 million.

- Regular software and application updates are critical, as many software updates address vulnerabilities found in computer operating codes.

Staff, Expertise, Roles and Responsibilities

The 3AB1 Port of Everett case study is an appropriate illustration of the importance of identifying, assigning, and following staffing protocols. The Port of Everett, as part of the joint Puget Sound Regional Maritime Transportation Disaster Recovery Exercise Program (Exercise Program), prepared and practiced Business Continuity and Resumption of Trade Planning (Continuity of Operations Plan [COOP]) in 2014. This plan has been reviewed and updated as needed each year. Although the plan did not specifically address pandemics, it provided a framework for Port leadership to use as a reference, or guiding document, that outlines actions and procedures that can be adapted to the event at hand. This is of key importance in responding to disruptions as staff and key personnel need to know who will be leading the response and recovery. In the case of multimodal transportation networks, DOTs and relevant government agencies need governance protocols to provide channels of communication that facilitate damage assessments and needs identification, early response actions, and coordination within and between public agencies and private sector partners with interdependencies.

Feedback, Updates, and Dissemination

The methods and tools used by agencies, organizations, or communities during disruptions will increase resilience of transportation networks only if they are properly outlined, revised, and updated to new standards or conditions. This was a prominent takeaway from the Baltimore Howard Street Tunnel Fire, which, although it happened 20 years ago, continues to provide a good practical lesson today. Being resilient also requires persistence and continuous improvement. There are straightforward reasons for the need for continuous improvement, like static systems degeneration and conditions of operational change. The former can be understood as the need for maintenance while the latter is the process of updating to new technologies, needs, and society.

Primer for Resilience-Planning Techniques

Implementation Guidance for Resilience Planning Techniques: Table B.1 classifies resilience-planning techniques as (1) frameworks, (2) training and capacity-building exercises, (3) modeling and analysis methods, (4) organizational arrangements, and (5) risk-based/asset-protection approaches. Implementing solutions in each of these classes requires (1) describing the rationale for applying the resource, (2) consulting a synoptic example of its prior application, (3) acquiring the ingredients needed for implementation (data, technology, staff), (4) following the procedure for successful execution, and 5) considering potential pitfalls or needed enhancements to prior examples. The following primer offers practical guidance for each class of technique.

Practical Steps: Implementing Frameworks

Description

Within the existing library of resiliency planning resources, there is a plethora of “frameworks.” Resiliency frameworks provide agencies, entities, and even individuals with a common approach or process for undertaking the steps necessary to be more resilient. Frameworks are not an end unto themselves, in so far as they only provide the means of organizing data, tools, analysis, coordination, and outreach required for incorporating resilience into an organization’s culture. The most common resilience framework identified in the research is the National Disaster Recovery Framework:

The National Disaster Recovery Framework (NDRF) establishes a common platform and forum for how the whole community builds, sustains, and coordinates delivery of recovery capabilities. … The primary value of the NDRF is its emphasis on preparing for recovery in advance of disaster. The ability of a community to accelerate the recovery process begins with its efforts in predisaster preparedness, including coordinating

with whole-community partners, mitigating risks, incorporating continuity planning, identifying resources, and developing capacity to effectively manage the recovery process, and through collaborative and inclusive planning processes. Collaboration across the whole community provides an opportunity to integrate mitigation, resilience, and sustainability into the community’s short- and long-term recovery goals. (U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) June 2016).

First developed in 2009, and updated in 2016, the NDRF is an all-hazards, whole-community approach to resilience based on five mission areas:

- Prevention

- Protection

- Mitigation

- Response

- Recovery

An important distinction of the NDRF is that it covers the entire cycle of resilience from pre-event planning to post-event recovery. Many of the frameworks identified in the research focus either on pre-event planning, often characterized by some version of “C” action verbs: Communication, Cooperation, Coordination, Collaboration, and/or Control; or they focus on post-event recovery featuring some version of “R” action verbs: React, Reboot, Retool, Reshape, Repair, and Restore.

Many of the transportation-related resiliency frameworks focus on pre-event planning and vulnerabilities. For example, in 2006 DHS also released a National Infrastructure Protection Plan (NIPP) based largely on pre-event planning. The all-hazards Risk Management Framework focused on protecting physical, cyber, and human resources (DHS 2006). The NIPP has six elements:

- Set security goals.

- Identify assets, systems, networks, and functions.

- Assess risks.

- Prioritize.

- Implement protective programs.

- Measure effectiveness.

It is not surprising given the broad coverage and all-inclusive design of the NDRF and NIPP that more customized frameworks have also evolved. For example, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency offers a climate-focused resiliency framework: Planning Framework for a Climate-Resilient Economy (EPA 2016). The EPA framework is a five-step process, focused on prevention, protection, and mitigation:

- Organize.

- Evaluate projected climate-change impacts and hazards.

- Identify community assets and their vulnerabilities.

- Analyze overall economic implications for the community.

- Explore options to enhance resilience and pursue opportunities.

FHWA also provides a climate-focused framework for improving resilience: the Climate Change & Extreme Weather Vulnerability Assessment Framework (FHWA 2012). The first edition vulnerability assessment framework consists of three primary components:

- Define objectives and scope.

- Assess vulnerabilities.

- Integrate vulnerabilities into decision-making.

In 2020, the FHWA Office of Planning, Environment, and Realty published a third edition of the framework: Vulnerability Assessment and Adaptation Framework. The framework is now more explicit in defining the steps under the framework:

- Articulate objectives and define the study scope.

- Obtain asset data.

- Obtain climate data.

- Assess vulnerability.

- Identify, analyze, and prioritize adaptation options.

- Incorporate assessment results in decision-making.

- Monitor and revisit.

Similarly, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has developed a cyber-focused version of the risk management framework, Risk Management Framework for Information Systems and Organizations (U.S. Department of Commerce, NIST December 2018). The cyber framework is based on seven steps:

- Prepare to execute.

- Categorize systems and information.

- Select controls.

- Implement controls.

- Assess controls.

- Authorize the system or common controls.

- Monitor the system and associated controls.

It should be noted that private sector freight enterprises have also developed frameworks for resilience that tend to focus more on operational flexibility than infrastructure protection.

Synoptic Examples

Several case studies developed for this research used existing or modified frameworks from those discussed in the previous section to improve the resilience of transportation networks. In many cases, adopting a framework is often the first step on the path to becoming a more resilient organization.

The ARC case study focused on ARC’s Vulnerability and Resiliency Framework, the Atlanta MPO derivative of the FHWA Climate Change & Extreme Weather Vulnerability Assessment Framework. The ARC framework focuses on transportation-related decision-making (see Figure B.5). Assessing vulnerability focused on transportation assets, as previous disasters demonstrated that transportation network failures significantly exacerbate large-scale disruptions, due to cascading effects/dependencies in the transportation system, and that transportation system resilience affects other policy areas. The ARC framework began by examining functional interdependencies and institutional relationships:

The framework was used to identify critical assets, facilities, and/or services in the transportation network, considering the effects of climate change on local environmental conditions, and then identify vulnerabilities by scoring their exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity. The anticipation that future conditions will be different from present conditions is central to the analysis, and a scenario-based forecasting tool was used to explore impacts under different assumptions and timescales. A combination of GIS, travel demand modeling, and expert guidance is used to make the assessment. The ARC vulnerability framework sought to link the risk appraisal to transportation decision-making, including impacts on other policy areas such as public health, and other planning efforts by partner agencies. Having an explicit framework made it possible to compare transportation policies and initiatives for conformity with resilience principles.

A case study in Florida highlighted the FDOT’s efforts to incorporate resiliency into the transportation-planning process. FDOT developed a guidance framework to assist the state’s 27 MPOs in incorporating resilience into their efforts as well. FDOT’s resiliency planning was

also an adaptation of FHWA’s Vulnerability Assessment and Adaptation Framework. Efforts by the FDOT and its partner agencies fall into the broad category of pre-event planning frameworks, appropriate for transportation networks in regions with reoccurring disruptions like hurricanes.

The Rhode Island case study highlighted a community planning framework as part of an implementation initiative of the Planning Framework for a Climate-Resilient Economy developed by the U.S. EPA. The EPA framework is oriented toward local economies that discuss planning and projects for transportation facilities and other important components of local economies like commercial establishments and utilities.

The Louisiana Supply Chain Transportation Council case study is another implementation of the NDRF. A key recommendation from Louisiana implementing NDRF was the creation of a public-private council that explored ways of using Louisiana’s extensive multimodal network to keep freight moving.

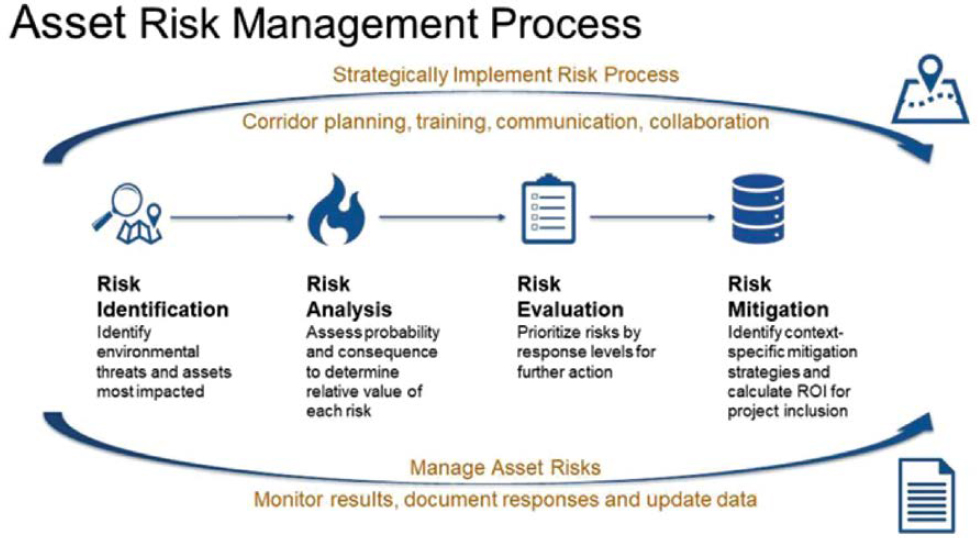

The Asset-Based Risk Management case study examined Utah’s version of the DHS-NIPP Risk Management Framework. While the Utah DOT’s implementation was viewed as a risk management process, as shown in Figure B.6, it bears many of the same elements found in the NIPP.

A strategic framework is a method for organizing priorities and initiatives leading to a high-level goal or purpose. During 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic, a historic hurricane season, record-setting wildfires, and the Solar Winds cyberattack resulted in numerous news stories, published articles, and online opinions. One commentary in an online magazine, War on the Rocks, made a pertinent argument for organizations to adopt a cyber-focused resilience framework, but the argument seems to resonate for all hazards:

Therefore, the sheer impossibility of a perfect defense has driven organizations, especially in the private sector but increasingly in government as well, to reorient their thinking around a risk management approach to resilience. In fact, for over a decade, organizations that contend with threats in cyberspace have been drawing on the logic of resilience and investing in developing and implementing resilience-based frameworks. While several frameworks exist, such as the Financial Stability Board’s cyber resilience toolkit, MITRE’s cyber resiliency engineering framework, or the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s systems security engineering approach, they generally share a few core

components. These typically include being prepared in advance of an incident, maintaining the ability to withstand and continue critical services during the course of an event, responding to and recovering from the disruption, and finally adapting and maturing an organization to incorporate lessons learned to be better prepared for the next incident (excerpt from A Grand Strategy Based on Resilience. War on the Rocks, Erica Borghard, Jan. 4, 2021).

Ingredients

In the review of frameworks for this research, there are several commonalities in either designing or adopting a resilience framework:

A Goal: Most resiliency frameworks start with a goal or objective statement, especially those that focus on either pre-event planning or post-event recovery. The framework establishes a process for achieving a goal or objective.

Governance: Defining roles and responsibilities, or who does what, varies in importance among the frameworks reviewed, at times appearing early in the process and at other times as part of coordination and cooperation that takes place once critical assets have been identified and threats assessed. In either case, governance should be closely tied to the next key issue, interdependencies.

Understand Interdependencies: Transportation and information networks most often involve or impact a wide range of associated partners. When elements of networks are disabled, communication and coordination among all partners become critical, as recent supply-chain experience due to the COVID-19 pandemic has made clear.

Inventory Assets: Once agencies or communities decide to adopt planning and mitigation strategies to be more resilient, they need to conduct an accounting of what assets they have that must be protected and prioritize those most critical.

Analyze the Threats: Recent history suggests that sometimes functional disruptions come from the least likely sources (i.e., coronavirus), so while broadly assessing potential threats may be necessary, the Arizona Desert or Wyoming Prairies are unlikely to experience mudslides that result in road closures.

Risk or Vulnerability Assessment: Assessing threats and vulnerabilities. Pre-event planning frameworks tend to focus on infrastructure whether physical, cyber, or human that could be incapacitated by a disruptive event. Post-event recovery frameworks often focus on prioritizing the restoration, recovery, or reshaping of disabled assets. Often data and/or data access is a key input to assessment activities.

Procedure

The most important consideration when incorporating a framework for resilience into transportation networks is to identify the framework that best fits the needs of a particular organization or region. The research suggests that many entities start with an existing framework that is modified to best meet their needs. For guidance, the research team developed a series of questions that organizations should ask themselves, such as the following:

- What is the goal or objective of the resilience effort?

- What is the geographic scope of the effort?

- Will the effort include just physical assets? IT assets? Other?

- Is the focus of the resilience effort focused on pre-event mitigation or the entire disaster recovery cycle?

- Who are the partners/industries that should be included in resiliency planning and coordination efforts?

- What existing resources, data, and/or tools does the organization have available to assist in the effort?

- What are the budgetary constraints or considerations for undertaking the effort?

- Are there opportunities for external resources to support the effort?

- What is the agency’s role and responsibility in the specific resiliency effort?

Pitfalls and Enhancements

A framework is not an end unto itself; it primarily provides a path forward. Adopting a framework for resilience will still require human capital, internal and external coordination among interdependent partners and industries, data to inventory and prioritize key assets, and possibly tools to perform analysis to support decisions. The research for this project suggests that many organizations start with an existing framework and then make modifications and enhancements as needed to fit their organization and goals.

Practical Steps: Training and Capacity Building

Description

Training and exercise are also critical elements of resilience planning. Training can help agencies and individuals identify vulnerabilities, address prevention, and consider mitigation strategies. Exercises help develop procedural memory around the actions required when a disaster occurs and facilitate recognition of the resources needed for recovery. Training and exercise programs are a proven method whether it is a community practicing for a mass casualty event or a family exiting a burning house. For larger organizations, management often turns to emergency management exercises for practice. These types of exercises vary considerably in both their complexity as well as their implementation, and they can be classified as discussion-based and operation-based exercises.

Types of Exercises

There are different exercises for evaluating program plans, procedures, and capabilities. Discussion-based exercises provide a communications forum for discussing and developing plans and procedures. Examples of discussion-based exercises include the following:

- Walkthroughs, workshops, and orientation seminars are basic training for team members. They are designed to familiarize team members with emergency response, business-continuity and crisis communication plans, and their roles and responsibilities as defined in the plans.

- Tabletop exercises are discussion-based sessions where team members meet in an informal, classroom setting to discuss their roles during an emergency and their responses to a particular emergency. A facilitator guides a participant through a discussion of one or more scenarios. The duration of a tabletop exercise depends on the audience, the topic being exercised, and the exercise objectives. Many tabletop exercises can be conducted in a few hours, so they are cost-effective tools to validate plans and capabilities.

- Game or simulation exercises are learning experiences that rely on simulations to train emergency response tasks and play out the results of the decisions made by participants. Through gameplay, players learn aspects of exploring the dynamics of preparedness. For example: using gameboards and playing cards, players group within the game community to decide how to invest credits to protect essential services.

Operation-based exercises involve deploying resources and executing plans and procedures. Examples of operation exercises include the following:

- Drills are a coordinated, supervised exercise activity, normally used to test a single specific operation or function.

- Functional exercises allow personnel to validate plans and readiness by performing their duties in a simulated operational environment. Activities for a functional exercise are scenario-driven, such as the failure of a critical business function or a specific hazard scenario. Functional exercises are designed to have specific team members practice the procedures, evaluate the policies, and use the available resources (e.g., communications, warnings, notifications, and equipment setup).

- A full-scale exercise is used to train against a scenario that mirrors the real disruptive event as closely as possible. It is a lengthy exercise that takes place on location using, as much as possible, the equipment and personnel that would be called on in a real event. Full-scale exercises are conducted by public agencies. They often include participation from local businesses.

Synoptic Examples

A universal good first step toward greater transportation network resilience in the face of any potential disruption is the preparation of an emergency/business-continuity plan that includes a risk matrix on the potential hazards that can affect an area or an entity. Using a hazard matrix can foster procedures and policies to be developed for identified hazards or to address characteristics of hazard types. For example, power outages can result from a multitude of events resulting in functional disruptions. No matter the cause, the functional result of a power outage, as an example, has a logical set of procedures that identify the critical needs that must continue through the outage, and actions that must be taken to retool and resume power. Several of the NCHRP Web-Only Document 391, Volume 1, case studies identified the use of training and exercise, including the following:

- Port of Everett: Pre-event plan training and exercising of their plan helped the Port identify gaps in the plans and prepare staff to quickly follow procedures and policies to use a coordinated path during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and governmental-enforced shutdowns of activities in early March 2020. Through the training exercises, Port Everett was able to use their plan to develop a specific response to the state-mandated shutdowns. The Port had procedures and policies in place that guided leadership through the early days of the pandemic and allowed the Port to continue to provide maritime services to their customer base and help keep the economic impact of the closure on the Port and their customers to a minimum.

- Howard Street Tunnel Fire: The absence of a coordinated training program resulted in delays in responding to the fire, causing additional damage to tunnel and communication infrastructure. In its accident brief on the train derailment and fire that followed, the NTSB made specific recommendations to the DHS about the need for training for rail employees and first responders (NTSB 2001). Looking back, more inclusive training across modes and between public and private parties would have improved the response and decreased the damage to all parties.

Other case studies did not specifically identify the use of exercises in the activities. However, if an agency or business has a plan in place, that plan could be tested using training and exercise activities to identify gaps to inform both the responders and the planners of elements that need to be changed and/or updated to prepare for future events. Based on the case studies reviewed, the research team identified several opportunities where training and exercise activities could offer a more comprehensive resilience strategy.

Games

A game is a structured form of play in which players engage in an artificial conflict. Games are often used as educational and training tools and are framed by a set of rules and metrics of performance around which the participants play. Usually, players manage resources through game tokens in pursuit of a goal.

- Supply Chains in the Midwest Amidst COVID-19 provide a good basis for “game-type” exercises. One game approach includes role-playing where the participants are assigned a role within the supply chain, with each role having a set of resources and rules (e.g., supplier, buyer, service provider, consumer.) This form of game has been used in TRB Annual Meeting resilience workshops over the last few years hosted by AMR20 Disaster Response, Emergency Evacuations, and Business Continuity Committee.

Tabletop Exercises

Tabletop exercises are an often-used method to test the viability of current resiliency plans in responding to natural disasters. These discussion-based sessions allow team members to meet and review roles and responsibilities during an emergency. There was limited discussion of training and exercise programs in the literature used to develop the case studies. In general, tabletop exercises can help agencies prepare for any type of disruption. For example, the Florida case study reviews a guidance document developed for MPOs in the state to incorporate resilience into long-range plans, but the guidance omits any reference to tabletop simulations. While it is likely that many agencies affected by a disaster have conducted exercises as a best-practice post-event activity, it is not well documented in the literature.

- Super Storm Sandy: Multiple agencies have exercises based on lessons learned.

Training and Exercise Ingredients

There are three main ingredients for designing successful training and exercise programs:

Design

- Clarify the objectives and outcomes.

- Choose the right participants and exercise team.

- Design an interactive discussion/scenario and exercise plan.

Engage

- Create an interactive, no-fault space (providing the group with the ability to openly discuss all points of view).

- Ask probing questions to gain insight.

- Capture issues, lessons, and key gaps.

Learn

- Prepare an after-action report.

- Create a specific, near-term plan for improvement.

- Provide tools and guides to boost learning.

Training and Exercise Procedures

These exercises may be carried out in several ways:

- Plan orientation is used to introduce or refresh participants to plans and procedures. This type of training may involve lectures, panel discussions, media presentations, or debriefing of past incidents for lessons learned.

- Tabletop exercises provide a convenient and low-cost method of introducing the staff to scenario-related problem situations for discussions and problem-solving. Such exercises test policies and procedures.

- Functional exercises are used to simulate actual emergencies or disruptions. These exercises involve the emergency operations staff and are designed to exercise procedures as well as test the readiness of personnel, communications, and facilities. Such exercises should be conducted at the emergency operations level, coupled with field exercises.

- Full-scale exercises are the most complex type of activity and the goal of the training program. This exercise is a full performance exercise plus a field component, which interacts with the emergency operations center or other agency leadership team through an exercise that has a specific scenario laid out for the participants, with simulated messages coming into play during the exercise that provide ongoing status reports or inputs as to the changing situation within the exercise. These exercises test the deployment of resources and operations field personnel.

Training and exercises can be viewed as a commitment to continuous emergency/business-continuity planning and preparedness. Based on practical experience from conducting and participating in resilience and exercise programs, the research team believes these programs can be incorporated into any resiliency plan or plan amendment. These programs will be an area of focus in developing transportation network resiliency planning guidance. When adopting a training and exercise program, an entity may want to ask the following questions:

- What are the goals of the exercise? For example, do you want to test your communication or incident notification procedures?

- Can exercise goals be measured? If so, how?

- Can you complete the scenario in the time allotted?

- Is the scenario realistic and relevant to the plan?

- Is the scenario timely to the current planning cycle?

Developing an Exercise Program

Developing an exercise program begins with an assessment of needs and current capabilities and a review of the risk assessment and program performance objectives. Conduct a walk-through or orientation session to familiarize team members with the preparedness plans. Review roles and responsibilities and ensure everyone is familiar with incident management. Identify probable scenarios for emergencies and business disruption. Use these scenarios as the basis for tabletop exercises. As the program matures, consider holding a functional exercise. Contact local emergency management officials to determine whether there is an opportunity to participate in a full-scale exercise within your community.

Exercises should be evaluated to determine whether exercise objectives were met and to identify opportunities for program improvement. A facilitated “hot wash” discussion held at the end of an exercise is a great way to solicit feedback and identify suggestions for improvement. Evaluation forms are another way for participants to provide comments and suggestions. An after-action report that documents suggestions for improvement should be compiled following the exercise, and copies of the report’s findings should be distributed to management and others. Suggestions for improvement should be addressed through the organization’s corrective action program.

Pitfalls and Enhancements

Training and exercise of plans are only as good as the agency’s commitment to developing plans and spending the resources in staff time to train staff on these plans. Activities include committing the resources to prepare after-action reports on the training and exercises that can be used in both future updates to the emergency and business/operations continuity plans. The after-action reports will also be useful for the preparation of future training and exercises for the plans. A general best practice is to exercise the plan at least every 18 months, although annual training and exercises are preferred.

While each business and public entity is unique, and there is no one-size-fits-all approach to disaster cleanup, restoration, and recovery, it is always a good time to begin planning and preparing for the future. By proactively taking specific steps to develop mitigation strategies that limit the effects of emergencies and disasters, asset owners and managers can protect employees and their organizations in the short-term, and prepare for recovery efforts.

In the wake of a disaster or disruption, detailed plans and procedures often take a backseat to stress and panic. While emotions and fear can be high in these situations, it is beneficial to have a prepared plan that can be used as the foundation for response, knowing that the leaders in charge must have the flexibility to respond to the particular elements of the disruptive event. Being able to refer to prior training and exercises will give leadership and stakeholders confidence in their short-term decision-making, as they respond to the event and do their best to continue operations, even if on a limited basis. These tools will provide building blocks that can be used as the organization makes plans and decisions for recovery.

Following the event, prepare an after-action report, detailing the event and the results, and identify the gaps in the response and/or plan and the needed changes to respond to future events. Create action plans that break down response, continuity, and cleanup responsibilities into manageable tasks to keep employees focused and positive about the restoration and recovery process.

Practical Steps: Selecting Organizational Arrangements

Description

Modern transportation networks are increasingly intricate composites of federal, state, local, and private infrastructure enabled and infused with information technologies. When disruptions occur that create chaos and crises, maintaining a sense of control and communicating openly and clearly with partners and appropriate stakeholders is cited repeatedly in academic and business literature examining natural disasters, cyberattacks, and pandemics among others. Organizational strategies related to resilience can be manifested by individuals, top leadership, or broad networking with partner agencies and stakeholders. Meyer et al. (2019) focused on resilience in the freight networks and noted the following:

The freight transportation system is an interdependent network of organizations with different missions, operations, and programs, with assets exposed to varying degrees of risks and vulnerabilities. The scope of advancing resilience for this interconnected system requires often complex, coordinated, and collaborative interactions and sophisticated freight management strategies.49

The New Zealand Transport Agency recently developed an interdependency organizational typology to help define the relationships between various elements of transportation and technology networks. The New Zealand typology specifically examines organizational interdependencies linked through shared ownership, governance, or oversight. In the United States, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, an arm of the DHS, has developed a series of plans examining the critical infrastructure partnerships across 16 private industry sectors and state, local, tribal, and territorial governments. Each of these plans examines the operating conditions and risk landscape within each industry sector.

From the individual perspective research on what comprises leadership and the traits that make a good leader has found a strong tie between leadership styles and organizational resilience:

… authentic leadership also contributes to organizational resilience. Organizational resilience refers to the agility needed to not only quickly respond to market changes, but to thrive during difficult times by identifying opportunities when faced with potential threats. When an organization is resilient, its employees feel empowered, secure, and even optimistic about the future.50

Synoptic Examples

A theme among the literature reviewed and case studies developed from this research is the need to provide guidance to a myriad of stakeholder organizations and agencies to work toward common goals, providing communication platforms to exchange information and developing institutional capacity and leadership to deal with unseen disruptions.

In the FDOT case study that examined the State of Florida’s efforts to incorporate resilience into the planning process, key elements of the efforts in Florida include resilience coalitions and the development of a Resilience Quick Guide. For example, the Tampa Bay Regional Planning Commission coordinates a regional resilience coalition, hosts a leadership summit to identify vulnerabilities and resilience needs, and provides resources to local governments through a resilience hub website.

A case study on cyber disruptions examines the NotPetya attack in 2017. A.P. Moller-Maersk, the world’s largest container ship and supply vessel operator in the world, was the most prominent of the many victims of the NotPetya cyberattack. Maersk transports about 15% of all containers moving in global trade and operates in nearly 80 port terminals around the world. For Maersk, the NotPetya attack began when an employee in the Ukraine responded to an email. Within hours, the shipping giant’s IT networks were completely disabled and most of its computers were irreversibly locked. In the immediate aftermath of the attack, Maersk management responded rapidly, with the company’s CEO involving himself in crisis calls and meetings to provide immediate guidance. A little over 1 week following the attack, Maersk resumed online bookings and began restoring normal operations.

Looking back on the NotPetya cyber disruption that Maersk estimated to cost nearly $300 million (USD) in lost sales and recovery efforts, senior management at Maersk reflected on the key lessons learned. In addition to several IT cyber response and recovery strategies, the company also offered the following advice: “Guidance and decisions taken by top management in operational level and media handling are vital to business continuity.”51 Others reporting about the impacts on Maersk and the company’s ability to quickly recover from such a global network disruption have lauded the company for its open and clear communications strategy. The company sent out daily updates to its partners about which operations and systems were up and running and which remained closed.

A third example is in response to the COVID-19 global pandemic. The World Health Organization (WHO) published interim guidance in March 2020 (updated in June 2020), on ways the global community could slow the spread of the virus: “Mobilize all sectors and communities to ensure that every sector of government and society takes ownership of and participates in the

response and in preventing cases through hand hygiene, respiratory etiquette, and individual-level physical distancing.”52

Ingredients

In their synthesis of case studies and interviews, Meyer et al. (2019) note that most public agencies and transportation firms they interviewed tended to view resilience from two perspectives: one from an incident response or recovery and the other from a broader network or systems perspective. The authors noted that while many public agencies and private firms have protocols in place to respond to and recover from incidents, most had not yet engaged in a systems perspective of resilience.

In summarizing the literature and case study findings, there are a series of resilience strategies including institutional and communication strategies that organizations should consider in becoming not only more responsive but also more resourceful. Some general organizational ingredients identified for being resilient included the following:

- Clear, Open Communications: Communication, coordination, and information sharing are key components identified by Meyer et al. (2019) for any cooperative effort. “The most important characteristic of effective communication/information dissemination was identified as a priority coordination among various stakeholders, especially in planning expected response and recovery strategies.”

- Social Networks/Building Social Capital: Looking back at Superstorm Sandy’s recovery efforts, Eric Williams with the New York City nonprofit Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development noted: “In the aftermath of the storm, active community networks in the city stepped up to play crucial stabilizing and supporting roles in impacted areas. … Social networks are a key factor in a community’s ability to be resilient in the face of environmental, social, and economic shocks. Looking at resilience more broadly across a community, those pre-existing habits of communication and interaction allow greater transmission of information, coordination, and distribution of resources during an emergency, which we saw in many communities following Superstorm Sandy.”53 From the case studies examining natural disasters, it is also apparent that a key element to bringing local communities together is to provide them with guidance that leads to uniform training and procedures so that everyone is working from a common set of instructions or framework.

- Building a Resilient Organizational Culture: Lessons learned from the NotPetya experience included the rising influence of IT professionals, not only in maintaining IT systems but in maintaining viable business operations. In a similar light, prior research examining environmental disruptions and response identified the need for hiring and training staff that has the right disposition to handle disruptions without losing focus. Meyer et al. (2019) suggested incorporating resilience into the organizational culture so that resilience practices become part of standard operating procedures. Cultural considerations include institutional mechanisms for coordinating with external organizations; decentralized decision-making to allow recovery efforts to move forward even when the normal chain of command is compromised; designation of emergency or essential staff who understand their role in a crisis; and employee retention—seasoned employees are more likely to know what to do when a crisis occurs.

- Resilience Starts at the Top: In his book, Authentic Leadership, the former CEO of Medtronic defines authentic leaders: “Such leaders have a role to play in the greater society by tackling public policy issues and addressing organizational and societal problems … authentic leaders genuinely desire to serve others through their leadership, are more interested in empowering the people they lead to make a difference.”54 Forbes leadership coach, Cheryl Czech, takes the role of authentic leaders one step further, “Authentic leaders create resilient organizations by establishing an atmosphere of psychological safety that inspires innovation. Companies that embrace risk can capitalize on opportunities in a way that those that are risk-averse cannot.

- Employees who feel psychologically safe think more creatively, embrace ambiguity, and ultimately take chances—all traits of resiliency.”55

Procedure

Having cohesive guidance or a playbook for implementing resilience strategies is an often-cited resource in successful resilience programs and is one of the key outcomes of this research. Adopting a resilience culture within an organization is highly dependent on its leadership, but PwC, a global accounting and business consulting firm, suggests that flexibility and the ability to change, not only in reaction to a crisis but to anticipate and evolve to meet future challenges, are important for a resilient organizational culture. PwC identifies six traits important to fostering a resilient culture, the first three traits are described as internal capabilities, and the second three represent an organization’s relationship with its customers or stakeholders:56

- Coherence: the ability to make mutually beneficial decisions.

- Adaptive capacity: the ability to adjust to potential dangers.

- Agility: the ability to implement decisions with the required speed.

- Relevance: the ability to consistently deliver on stakeholder needs.

- Reliability: consistently delivering expected quality.

- Trust: knowing how to create investment-worthy or rewarding relationships.

The Resilience Quick Guide produced by the FDOT encourages an MPO to adopt performance measures related to resilience goals. The Martin MPO is highlighted in the guide for its efforts to adopt the following resilience measures in its LRTP:57

- Centerline miles of roadway on evacuation routes operating at or better than the adopted level-of-service standard.

- Acres of impacted wetlands or significant wildlife habitat.

- Percent vehicle miles of travel operating at or better than the adopted level-of-service standard on freight corridors.

Pitfalls and Enhancements

Much of the research on resilience-planning efforts has examined organizational failures due to disasters and disruptions. Human resources (HR) research on resilient organizations has taken a different approach, examining employee satisfaction and well-being among various organizations. The research suggests that organizations that cannot bounce back after a disruption are often stressful places to work:

A key to a resilient organizational culture is empowerment, which can come in many forms. Employees need to be given the freedom to take regular renewal breaks throughout the day to help rejuvenate, metabolize, and embed learning.58

The type of employee autonomy and empowerment suggested in the HR research is often a difficult practice to implement in a public sector setting (but one that many organizations were forced to accept during the COVID-19 pandemic).

Given the increasingly disruptive landscape due to environmental, cyber, and societal phenomena, research about the metrics of resilient organizations is growing. One of the trending insights during the COVID-19 pandemic is Organizational Network Analysis (ONA), which examines the human networks formed when employees collaborate through meetings, emails, instant messages, and calls:

“Traditional measures of organizational resilience such as financials and employee retention emphasize outcomes and cannot be managed in real time. Conversely, ONA makes behaviors associated with resilience immediately and dynamically visible across an organization. It gives us data-driven information about how to course-correct even in the midst of crisis and prepare for future shocks.”59

Practical Steps: Applying Analytical Methods

Description

Analytical tools provide a formal approach to measure, compare, select, and rank options for alternative implementations that seek to increase transportation network resilience. Analytical tools use data, analysis, and visualization to help quantify the benefits associated with such implementations as increasing highway capacity, building a new bridge, or increasing vehicle fleet.

The usefulness of analytical tools, however, is conditioned by organizational context and available resources. Hence, first, it is necessary to investigate whether an analytical tool is feasible to implement. Insightful questions include the following:

- What is the purpose of the use of the analytical tool?

- Does the analytical tool need to be developed or procured?

- What data does the agency have available and what data will be needed?

- What is the current use of analytical tools in the agency?

- And what is the technical expertise of the staff?

The answers to these questions will provide guidance on whether the analytical tool represents a viable alternative and will help narrow down the type of analytical tool that can be used. For example, if there is a travel demand forecasting model currently in use, then there exists a data collection and visualization method in place. Hence, the ability to use network modeling and optimization to increase resilience of the transportation network is a potential alternative. Next, it is important to gather information on key aspects of the network and assets already available to the agency. For example, ask the following:

- How complex (maybe valuable) is the transportation network/assets the agency is seeking to analyze or protect?

- How exposed or vulnerable are the assets to the most likely hazards? For example, how would one rank the risk of a significant impact on the assets on a scale of 1 (low) to 10 (high)?

- What is the anticipated cost of the analytical tool or method, including the data collection and resources needed to support the analyses?

- Is there a resilience funding opportunity or program that a model or tool will support in the application for funds?

Some of the benefits of using analytical tools include the following:

- Cost: they are normally less costly than full or even partial implementation of the resilience strategy and/or the modification of the physical object under study.

- Development and testing of alternatives can take less time than real implementation of the resilience strategy (particularly with the use of computer aid simulation or modeling).

- In the presence of multiple alternatives, they allow a fair comparison to determine the best alternative.

- They provide a better understanding of the alternative implementations to increase resilience under study.

Synoptic Analytical Tools Examples

Several case studies presented in NCHRP Web-Only Document 391, Volume 1 highlight analytical tools developed or implemented in resilience-planning efforts or disaster recovery. Case studies 3B5: Super Storm Sandy and 3A2: Climate Ready Boston focus on models employed for mitigation and preparedness. These two case studies focused on understanding and mitigating the impacts of rising sea levels due to climate change. The analysis included models that were supported by expert opinion to determine priorities for investments to mitigate rising sea levels and related

hazards. Both case studies used flood models to establish risk areas and priority investments. Case Studies 3A8: Pedestrian Flow Path; 3A9: Typhoon Emergency Response; and 3B5: Super Storm Sandy focused on disaster response and used analytical tools for the evaluation of alternatives. For example, the Pedestrian Flow Path model determined the best routes to be used for disaster evacuation based on which roads were predicted to be closed due to flooding.

Important Considerations

Every case study described in the NCHRP Web-Only Document 391, Volume 1, described different disruptive events and approaches for how to plan and respond. There are commonalities among the cases highlighted: