Incorporating Resilience into Transportation Networks (2024)

Chapter: 6 Play to Win: Build a Resilience Program and Learn from Experience

PLAY 6

Play to Win: Build a Resilience Program and Learn from Experience

Network resilience must be addressed within the practical context of a transportation agency’s overall business process. This play provides direction for how the previous plays in this playbook can be coordinated to explore broad questions about network needs and opportunities, including how a resilience team (or planner) can select an appropriate framework for implementing network-level improvements, assess the context for delivering improvements effectively, and build the capacity for ongoing resilient performance throughout the network resilience ecosystem.

Integrating the Network Perspective to Wider Agency Approaches

A critical play in any network resilience effort is integrating the network perspective into the context of an agency’s larger resilience program. An agency’s approach to resilience may be far-reaching, addressing not only the overall network performance and supply-chain concerns of this playbook but also operational concerns, strategies to leverage asset management, project-design techniques, operations and maintenance practices, emergency response planning, technology and materials selections, and technology/cybersecurity policies. Published NCHRP reports provide excellent guidance on this topic. A recommended starting point is NCHRP Report 976: Resilience Primer for Transportation Executives, which provides a high-level integration of resilience principles from other research into a holistic view for a transportation agency. Likewise, Incorporating Resilience into Transportation Planning and Assessment, the final report from NCHRP 8-36, Task 146, is another good starting point. These resources can provide insight into where and how in the agency’s business process network perspectives can create the most value.

Coordinated Plays

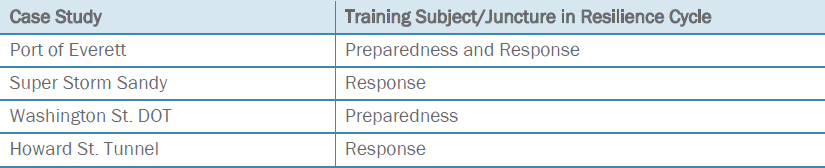

It is possible to apply all the plays in this playbook consistently, with the different self-assessments, toolkit resources, and Transportation Network Resilience Awareness Challenge modules informing each other and leading to a practical set of projects and policy actions that can be inserted into agencies’ business processes. Figure 44 describes how playbook resources can inform each other to build an overall resilience program with a high-quality team, agenda, assessment of needs, and solution sets.

Select a Resilience-Planning Framework

There is a wide selection of resilience-planning frameworks available to guide a resilience program. The frameworks are essential for determining factors such as how resilience is understood in the program, how objectives are established and satisfied, what dimensions of the network are considered, and how progress is measured. The results of the network resilience exercises

summarized in Figure 44 can provide important context for selecting which framework (or combination of frameworks) will fit any given program.

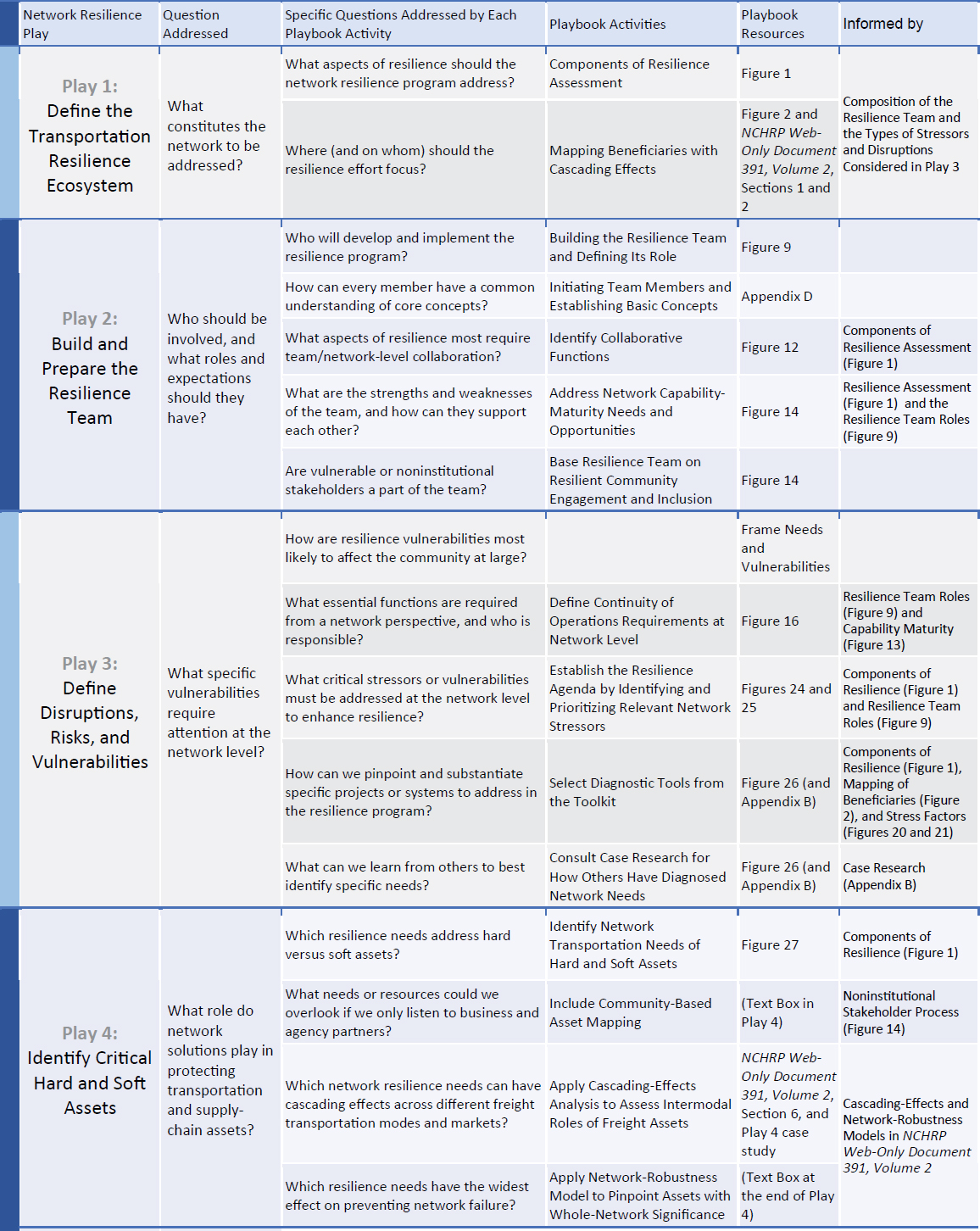

To select a resilience framework, the first question to ask is why network resilience is being considered at all. Are resilience questions predicated on concerns raised by specific events or constituencies, or are they top-down, agency-wide prerogatives? The best-fitting framework will be one designed to organize different datasets, tools, analyses, and financial and scenario plans to satisfy the program’s overall policy concern. Appendix C provides examples of documented resilience-planning frameworks that transportation agencies and coalitions have applied successfully. Appendix B explores how the body of case research (included in NCHRP Web-Only Document 391, Volume 1) highlights both the successes and challenges of agencies putting these concepts into practice. Figure 45 offers pragmatic steps for selecting a resilience framework for any given program.

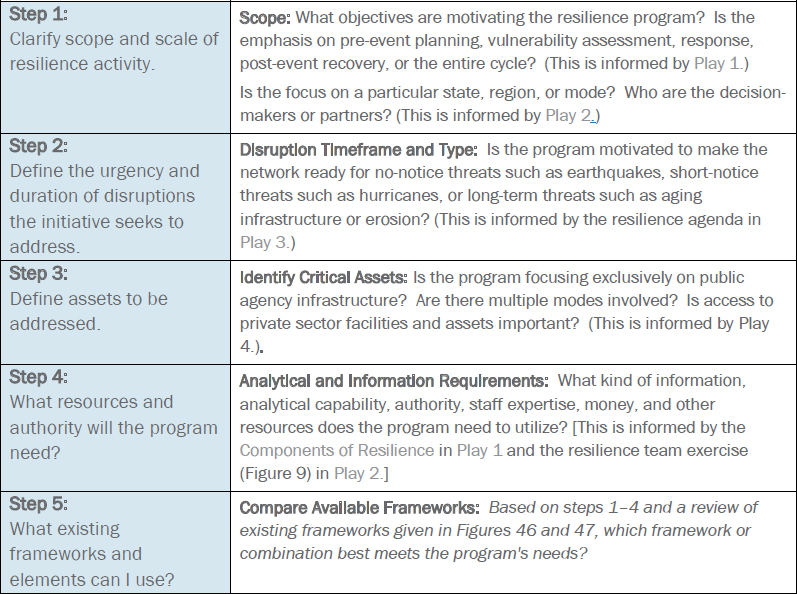

Figures 46 and 47 provide a catalog of frameworks that have been applied to transportation network resilience programs in the United States. They include broad federal frameworks driving policy at the national level, as well as local, regional, and statewide frameworks structuring

programs for all modes of transportation. Figure 46 lists several frameworks and provides guidance for when and how to apply them. The frameworks are fully described within the context of their original implementation context and characteristics in Appendix C.

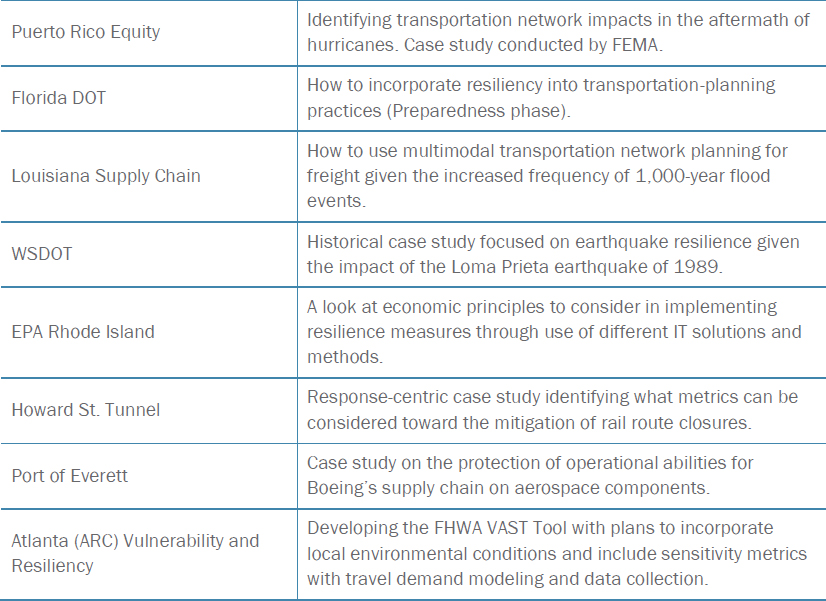

In addition to the description of frameworks provided in Appendix C, it is helpful to consult the practical cases in which these frameworks have been applied. Figure 47 provides a listing of documented cases (fully documented in NCHRP Web-Only Document 391, Volume 1) where the frameworks were developed and applied.

Puerto Rico After Hurricanes Irma and Maria: A Resilience Framework in Action

In 2017, Puerto Rico was hit by two consecutive hurricanes, Irma and Maria. As a result, the island’s roadways, power grid, natural environment, and access to water suffered major damage. Given the destruction, supply chains were also left unable to transport goods and services in a timely manner. Although hurricanes like these are unavoidable, inadequate planning across the resilience scale, from preparation to response and recovery, exacerbated the negative impacts. The FEMA developed a case study that put forward key planning metrics aimed at avoiding similar calamities during future storms:

- Scale responses for concurrent, complex incidents; have measures and resources ready for delivery to multiple locations.

- Staff for concurrent complex incidents; institute a robust plan that distributes aid workers to multiple locations.

- Sustain whole-community logistic operations; hire more staff and ship commodities from neighboring supply chains such as the U.S. Virgin Islands and Caribbean distribution warehouses.

- Respond during long-run infrastructure outages; consistently conduct field assessments, air reconnaissance; crowdsource information.

- Direct care to the initial housing operation; facilitate transitions from shelters to houses.

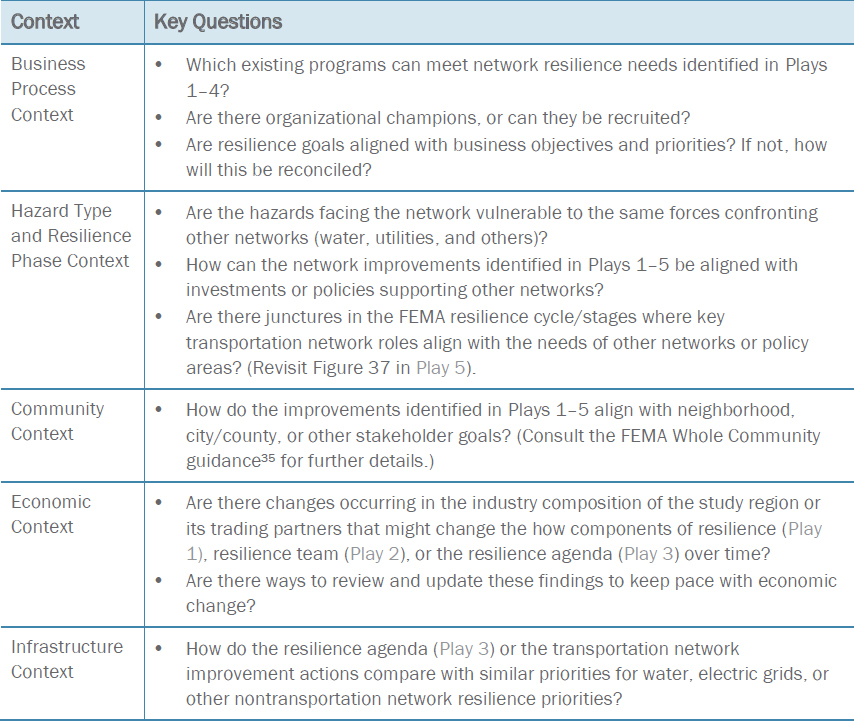

Match the Resilience Program to the Context

Because there is no one-size-fits-all network resilience program design, it is important to assess the policy context in which the resilience agenda is undertaken. Figure 48 provides a guide for contextualizing network perspectives on resilience and implementation of the solutions emerging from Plays 1–5. Appendix B describes how to assess different aspects of resilience context when implementing a network-level transportation initiative.

Build Capacity, Training, and Development

The network capability maturity exercise in Play 2 (Figure 16) can reveal how different actors within the network ecosystem not only have different levels of ability to contribute to network solutions but also have different interpretations of resilience concepts. For example, a private firm managing an entire supply chain will have specific business requirements articulated in terms that may not be familiar to transit operators, highway planners, or engineers. Furthermore, elected and appointed leaders exercising local zoning authority or serving on committees that constitute a resilience team may learn “on the job” with different ideas about both the network and its resilience. Capacity building is vital both to (1) establish a minimum baseline understanding of resilience concepts and (2) resolve any differences in nomenclature or the way concepts are interpreted.

Make the Most of Transportation Network Resilience Awareness Challenge

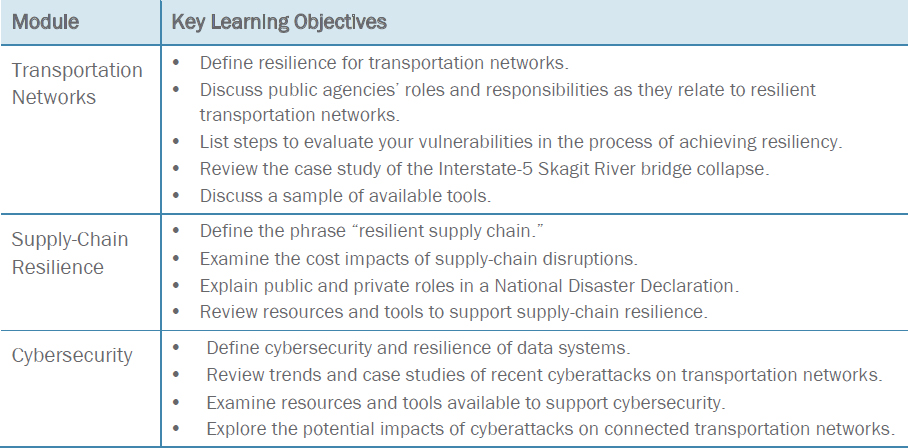

Addressing resilience at the network level requires a different level of understanding than other resilience training and capacity-building endeavors. As explored in Play 2, even the most

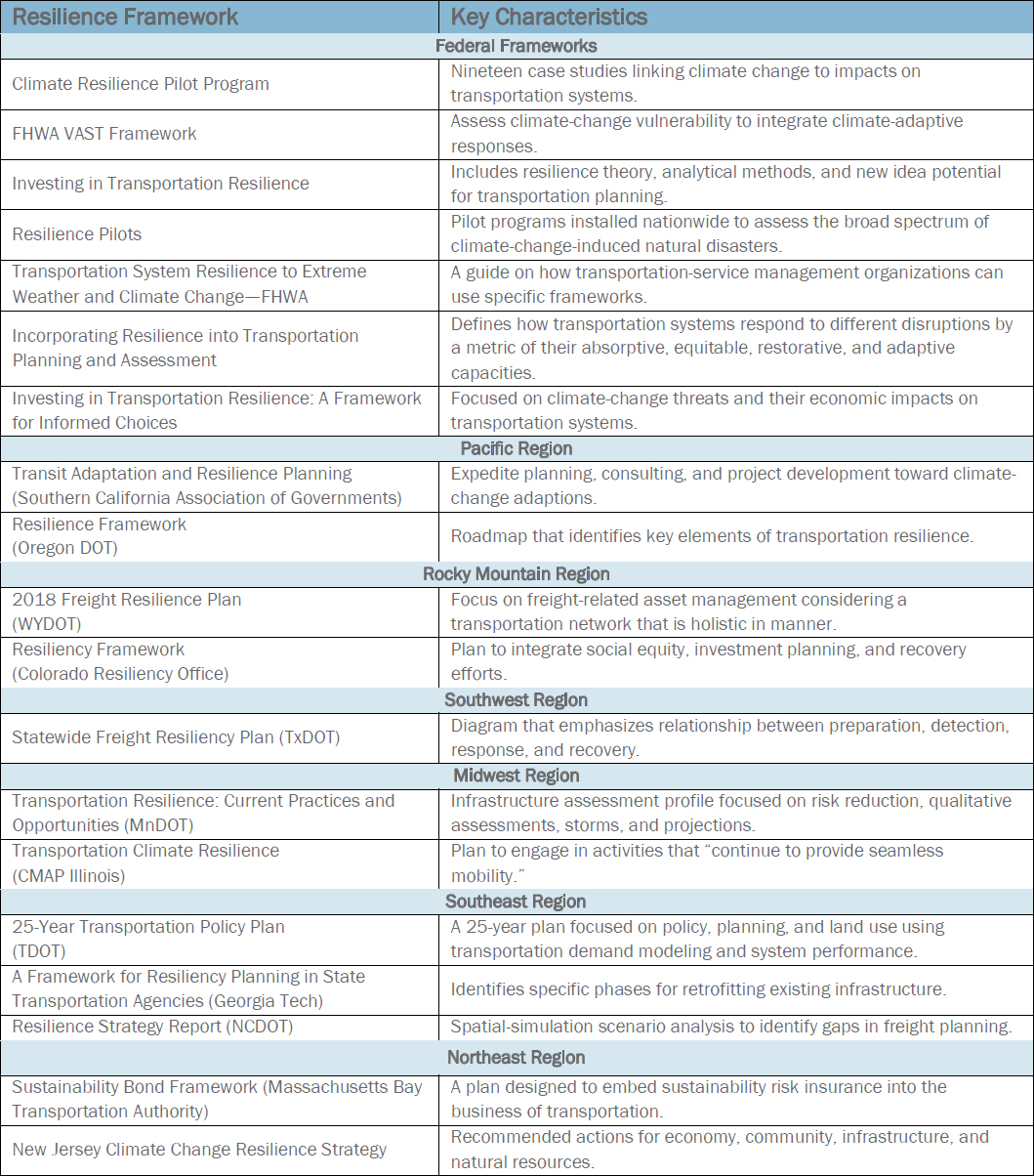

resilience-proficient individuals within an organization usually need additional knowledge and perspective to function as part of a network-wide resilience team. The Transportation Network Resilience Awareness Challenge documented in Appendix D provides a capacity-building resource that can facilitate common understanding of network-level transportation resilience concepts for all members of the resilience ecosystem. Figure 49 conveys the educational content of each of its three modules and potential contexts for its implementation.

The Transportation Network Resilience Awareness Challenge can be understood as an initiation resource for members of the resilience team and supporting organization to arrive at a starting point in their collective capacity. Ideal initiation opportunities to provide this baseline include the following:

- Formation of the Resilience Team: When a resilience team is first defined, as described in Play 2, individual team members should complete the resilience network awareness challenge. Follow up the “homework” assignment with a workshop to discuss the concepts and how they apply to the initial SWOT/components of the resilience exercise (described in Play 1).

- Expanding or Transitioning Memberships: When new members join a resilience team, completing the Transportation Network Resilience Awareness Challenge and associated assessments can ensure their readiness to contribute to the team and sustain a consistent view of the initiative.

- Elected and Appointed Officials: Jurisdictions with an interest in a transportation network strategy may require newly elected or appointed officials to complete the challenge as part of their orientation even when individual officials are not joining the resilience team. Such a requirement could facilitate better awareness and dialogue of network resilience issues if applied to new members of city councils, local planning boards, MPO committees, statewide transportation commissions, or legislative committees.

- Jurisdictions with Limited Staff or Experience: In jurisdictions with limited staff or little in-house expertise in freight transportation or network resilience, the Transportation Network Resilience Awareness Challenge can be an ideal part of job orientation for a planner or administrator. Because the modules are self-paced and take only 20 to 30 minutes to complete (meaning they can be done during a lunch hour or in a few sittings of a single week), the resource can provide a baseline level of awareness about transportation network resilience.

Selecting Ongoing Exercises and Training Opportunities and Exercises

The capability maturity exercise in Play 2 (Figure 16) can serve as a resilience team’s starting point to identify ongoing training and capacity-building needs. Using this process can (1) elevate priorities for building capacity among all organizations that form the resilience team (which may differ from the internal needs of any single organization) and (2) create opportunities for one organization to train its peers on concepts in the resilience ecosystem.

Objectives: While objectives for each resilience program will vary, they should be articulated in the program’s concept of operations. The objectives should clearly articulate how each training offering will:

- Help agencies and individuals identify vulnerabilities and consider mitigation strategies.

- Develop procedural memory and recognition of the resources needed for disaster response and recovery actions.

- Practice and rehearse disruptive events to identify opportunities and weaknesses not previously understood.

Types of Exercises

Walkthroughs, Workshops, and Orientation Seminars are basic training for team members. Activities such as the Transportation Network Resilience Awareness Challenge are designed to familiarize team members with emergency response, business-continuity and crisis communication plans, and their roles and responsibilities as defined in the plans.

Tabletop Exercises are discussion-based sessions where team members meet in an informal setting to discuss their roles during an emergency and their responses to a particular emergency. A facilitator guides participants through a discussion of one or more scenarios. The duration of a tabletop exercise depends on the audience, the topic being exercised, and the exercise objectives. Many tabletop exercises can be conducted in a few hours, so they are cost-effective tools to validate plans and capabilities.

Game or Simulation Exercises are learning experiences that rely on simulations to train emergency response tasks and play out the results of participants’ decisions. Through gameplay, players learn the dynamics of preparedness. For example, simulation exercises often use gameboards or playing cards to represent the community and decide how to invest credits to protect essential services.

Operation-Based Exercises involve deploying resources and executing plans and procedures. Examples of operation exercises include the following:

- Drills are coordinated, supervised exercise activities that normally are used to test a specific operation or function.

- Functional Exercises allow personnel to validate plans and readiness by performing their duties in a simulated operational environment. Activities for a functional exercise are scenario-driven, such as the failure of a critical business function or a specific hazard scenario. Functional exercises are designed to have specific team members practice the procedures, evaluate the policies, and use the available resources (e.g., communications, warnings, notifications, and equipment setup).

- Full-Scale Exercises are used to train for scenarios that mirror real disruptive events as closely as possible. They are typically lengthy exercises that take place on location using, as much as possible, the equipment and personnel that would be called on in a real event. Full-scale exercises are conducted by public agencies and often include participation from local businesses.

Learn from Past Experience and Examples of Practice

When selecting and designing an ongoing resilience program at the network level, it can be helpful to explore how resilience training programs have worked in other jurisdictions. Figure 50 lists the case studies presented in NCHRP Web-Only Document 391, Volume 1.