Incorporating Resilience into Transportation Networks (2024)

Chapter: 3 Define Disruptions, Risks, and Vulnerabilities

PLAY 3

Define Disruptions, Risks, and Vulnerabilities

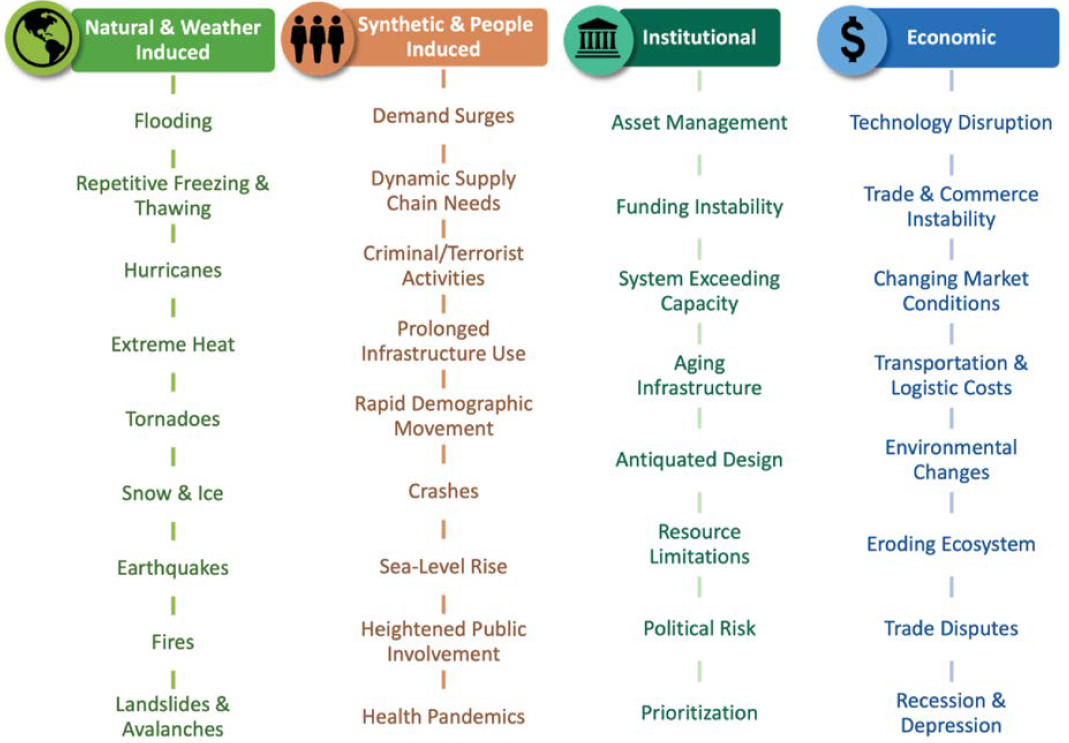

The range of potentially disruptive events and risk impacts is more complex when considering an entire transportation network than a singular asset or system. Furthermore, human-caused events such as cyberattacks, pandemics, energy shortages, and trade disputes may have cascading effects on the network, rather than compromising a single transportation asset. The same is true of natural events such as tornadoes, fires, and floods, which can alter the sourcing and routing of goods and create new bottlenecks, safety challenges, and mobility demands seemingly overnight, even when they do not directly harm highways, bridges, ports, or rails.

Defining risks, disruptions, and vulnerabilities at the network level begins with assessing what is required to sustain continuity of operations for both the infrastructure providers (highway, transit agencies, ports, and others) as well as the users managing demand (shippers, carriers, retailers, 3PL firms, and others). When these requirements are understood, it is easier to pinpoint vulnerabilities facing transportation agencies and customers that may directly or indirectly compromise performance. A typology of network stressors can be applied to perform a self-assessment of likely and significant disruption threats and thereby select the best diagnostic tools from the resilience toolkit (see NCHRP Web-Only Document 391, Volume 2). While top-down institutional assessments for transportation agencies and associated businesses are essential, it is not adequate to limit the network vulnerability assessment only to businesses and agencies. It is likewise crucial to equitably assess disruptions, risks, and vulnerabilities through the words and perspectives of individual workers, households, and communities playing a vital role in any disruption response.

Frame Risk and Vulnerability from a Social Equity Perspective

Beginning from a social equity perspective can have a profound impact on how a resilience team defines vulnerabilities, disruptions, and risks. Because established agencies and corporations play such a large role in the following assessments, a resilience team needs to establish an early focus on the needs of individual workers, households, neighborhoods, and businesses as intended beneficiaries of resilience planning. If a resilience team does not create a focus on at-risk or underserved noninstitutional stakeholders at the beginning, there is a significant possibility that resilience planning may be reduced to communicating institutional decisions and needs to the most affected participants in the network instead of identifying and responding to community needs. The team can follow a 12-step process to develop an inclusion strategy that informs how the team will undertake all subsequent assessments. This 12-step process can be followed (1) at the outset of the process of identifying resilience needs to direct the

team to specific areas and issues that might otherwise have been overlooked, (2) at the beginning and end of the self-assessment and diagnostic processes offered throughout Play 3 to invite consideration of noninstitutional and social equity perspectives, and (3) to review the needs profiles and resilience agenda (described further in the Set the Resilience Agenda section in this play) resulting from the execution of this play.

The Resilience Agenda is the prioritized subset of disruption shock or stress factors the resilience team seeks to address through its program.

Risk Management and Continuity of Operations

Before determining a transportation network’s risks and vulnerabilities, it is necessary to define its users and operational requirements. Resilience teams should be able to provide clear answers to critical questions: Who uses the transportation network? What functions do users depend on? What conditions must be met for this network to adequately perform its transportation functions? Threats to these essential requirements serve as a guide to defining and prioritizing risks and vulnerabilities.

Continuity of operations planning (COOP) is a process transportation agencies use to identify critical requirements and plan for effective responses to disruptions in the transportation network. COOP is a vital process for both public agencies and private firms.

What Is Continuity of Operations Planning?

COOP planning offers transportation agencies a way to define activities that must be performed if an emergency denies access to essential operating and maintenance facilities, vehicle fleets, systems, and senior management and technical personnel.

—TCRP Report 86/NCHRP Report 525, Volume 8 (2005)

TCRP Report 86/NCHRP Report 525: Transportation Security, Volume 8: Continuity of Operations (COOP) Planning Guidelines for Transportation

Case Study in Defining Vulnerabilities: Climate Ready Boston

The city of Boston developed the Climate Ready Boston initiative as a response to the challenges of climate change, including flooding, snowstorms, and hotter summers. The city worked with climate scientists, engineers, planners, and designers to identify vulnerable locations and develop strategies to promote resilience.

The plan includes a detailed asset inventory that combines more than 100 datasets to identify individual and systemic vulnerabilities, interdependencies between different assets and amenities, and existing resilience measures. The list of vulnerable assets includes both fixed-guideway transit and major roads. The plan also identified vulnerabilities for the city’s transit-dependent population. Other vulnerabilities included rail impairment due to high temperatures, and roadway buckling on asphalt roads experiencing subsurface moisture. Stormwater vulnerability was predicted to increase due to outfalls being unable to discharge because of higher sea levels. Underground transportation infrastructure was also identified as a special risk.

Resilience strategies include adapting existing buildings to changing conditions through local planning, constructing urban ecological (also known as “green”) infrastructure such as flood-resilient parks and other amenities, and district-scale flood barriers. Other proposed actions include education and readiness training, local planning efforts, infrastructure-investment prioritization frameworks, rezoning, and climate adaptation of municipal buildings.

Currently, insurers underestimate the risks of extreme storms and associated disruption due to failures in communication, power, and transportation. So, Climate Ready Boston also includes financial initiatives, including evaluating the current flood insurance market, engaging in better flood-risk ratings, and advocating for changes in the National Flood Insurance Program.

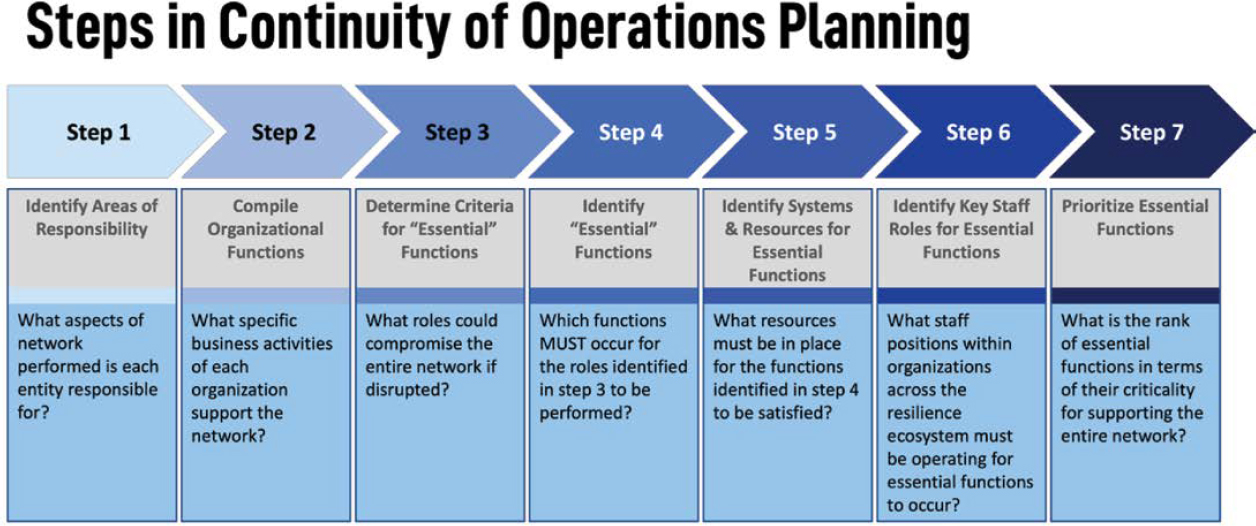

Agencies (2005) offers a starting point for establishing COOPs for both state DOTs and transit agencies. Figure 16 illustrates the steps suggested in TCRP Report 86/NCHRP Report 525, Volume 8, for developing a COOP.18 The report offers a seven-step process, with practical worksheets and exercises, that can be used to develop a well-defined and prioritized COOP strategy for either public agencies or private organizations. A network resilience team, as described in Play 2, can build on these steps to consider COOP requirements not only for an individual agency but also for the network. The principal difference in developing a COOP at the network level versus the agency or organizational level is the broader range of network functions and organizational roles that must be considered. Adapting the process outlined in Figure 16 to the network level requires resilience teams to pay particular attention to steps 1 and 2 and how a change in scale from an individual asset to an entire transportation network affects relationships through the subsequent steps. For example, a resilience team could undertake a network-level seven-step COOP process

within a long-range plan, a corridor study, or a standalone project. When completed, a network-wide COOP can serve as a valuable tool for defining vulnerability and disruption concerns.

In addition to the seven-step process shown in Figure 20, FEMA also provides a COOP toolkit that includes practical guidelines for initiating COOP processes, building and maintaining COOP capabilities, training staff and partners in COOP, and using available national resources for both COOP development and implementation.19

From Risk Management to Strategic Resilience

Assessing risk from the standpoint of continuity of operations across the entire network gives a resilience team a wider lens for considering potential disruptions than agency-specific or asset-specific approaches. Historically, the practice of risk management has presumed that an agency (or a private sector shipper or operator) can (1) pinpoint specific risks, (2) quantify likely risk implications, and (3) manage the potential cost or loss associated with such risks.

COVID-19 Paradigm Shift

“In the past, [the] risk management focus was on a small number of well-defined risks … now, risk is encompassing the broader mandate of resiliency management. It is woven into long-term strategy development.”20

McKinsey/FERMA Survey (2022)

Figure 21 compares the types of disruptions that have caused state DOTs, traffic management centers (TMCs), and transit agencies to trigger a COOP plan. The most common disruptions cited in the 2004 survey included fires, snow/ice storms, power outages, building/facility failures, flooding, terrorist events, and failure of communications systems.

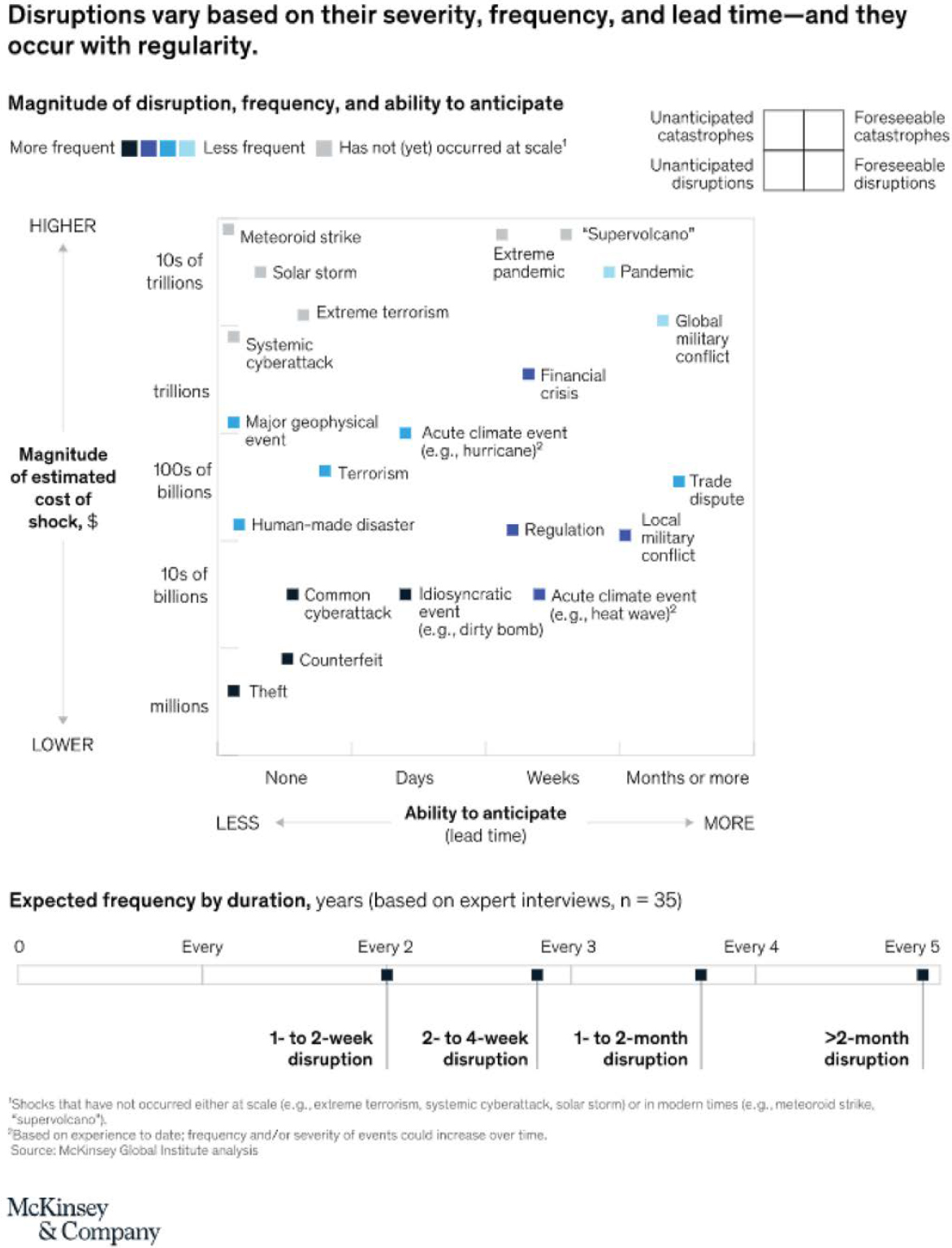

Figure 22 shows disruption types, their anticipated and foreseeable status, and their magnitude and duration as understood by business managers in 2020. It is notable that the list, compiled by the global consulting firm McKinsey, reveals widespread concern about biological pandemics, trade disputes, military conflicts, and cyberattacks. Compared to the earlier 2005 NCHRP/TCRP survey, there appears to be greater awareness of vulnerabilities stemming from cyberattacks, the COVID-19 pandemic, civil disturbance, and other emerging threats.

Figure 20. Steps in the COOP process for improving network resilience.

Figure 21. Types of disruptions in transportation agencies triggering COOP activation.

Figure 22. Disruptions of concern to private firms in 2020.

When considering the entire network ecosystem, it is also important to consider threats that may not directly affect internal operations of public agencies but can greatly affect how shippers, carriers, and households use the transportation system. The 2021 U.S. Census Small Business Pulse Survey makes several observations about private sector disruption concerns in the aftermath of the 2020–2021 COVID-19 pandemic and associated supply-chain disruptions.21 The survey shows that 38.8% of U.S. small business respondents were experiencing disruptions in supply, affecting 64% of responding manufacturing establishments, 59% of retail establishments, 59% of construction establishments, and 51% of accommodation and food service establishments. The 2020 McKinsey report, Risk, Resilience, and Rebalancing Global Value Chains, provides an overview of network disruption concerns among private firms on the demand-side of the resilience ecosystem.22

In light of the growing diversity of disruption threats illustrated in Figure 22, it is helpful to view a network resilience initiative or program from an all-hazards perspective.23

The all-hazards or strategic resilience approach shifts transportation agencies’ focus from preparing for singular disruptive events (risks) to assessing the capacity of the entire network ecosystem to absorb and recover from a wide range of unforeseeable risks. The components of resilience assessment identified in Play 1 support networks that do not hedge against singularly identifiable risks but rather prepare the network ecosystem for a wide range of possible risks and disruptions. A 2022 survey of more than 200 executives by McKinsey & Company, together with the Federation of European Risk Management Associations (FERMA), finds the COVID-19 pandemic exposed systemic vulnerabilities in business and supply networks.24 More than half of the respondents indicated that the pandemic has made risk and resilience significantly more important to their organizations. The survey shows that 75% of responding managers believe that the most important actions to address vulnerabilities exposed by the pandemic will be to improve risk culture and strengthen the integration of resilience in the strategy process.

The holistic all-hazards approach to resilience planning is also emerging for public sector transportation agencies. NCHRP Research Report 1014: Developing a Highway Framework to Conduct an All-Hazards Risk and Resilience Analysis25 offers a common lexicon/terminology for risk and resilience analysis and a roadmap of risk assessment research, which complement the plays in this playbook (Pena et al. 2023).

Consider Potential Transportation Network Disruption Types

Instead of attempting to exhaustively brainstorm every possible disruption on a network, resilience teams should consider the underlying sources of disruption in the overall resilience ecosystem. For example, an institutional weakness of underfunded highway and bridge preservation programs could create a network-wide vulnerability to disruptions from infrastructure failure, obsolescence, or incapacity.

Figure 23 lists four types of forces that can disrupt a transportation network.26 The four areas shed light on all three dimensions of the resilience ecosystem and provide a cross section of specific vulnerability drivers to consider in resilience planning.

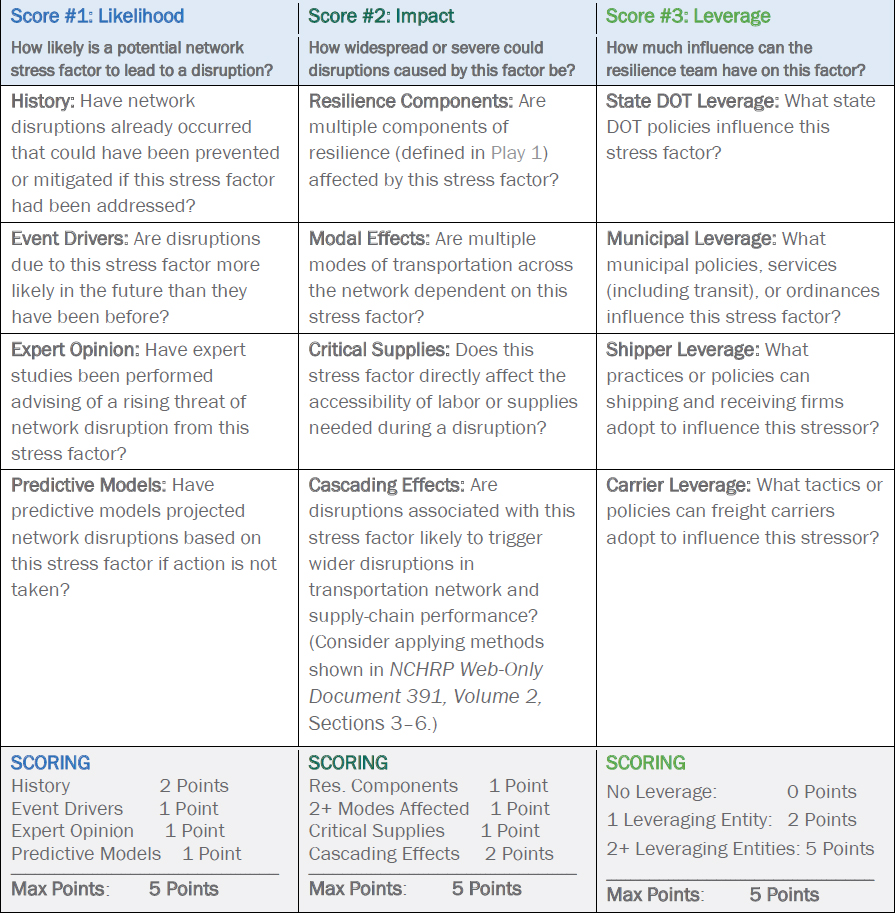

Due to the wide range of disruptions that can affect network performance (as shown in Figure 21 and Figure 22), transportation agencies can benefit from establishing a customized network disruption profile highlighting the most relevant disruption concerns. A resilience team can compile a prioritized set of resilience issues specific to a given transportation network using self-assessments like the ones described in Figure 24 and Figure 25.

Figure 23. Disruptive forces affecting networks.

Set the Resilience Agenda

The resilience agenda for a transportation network can be understood as the prioritized subset of underlying disruption stress factors the resilience team seeks to address through its program. The agenda is made up of policy, infrastructure, economic, and management issues the team aims to address through its program. The agenda can be based on (1) the likelihood that a shock or stress area will create a disruption, (2) the potential magnitude of impact that such a disruption can have at the network level, and (3) the degree to which the stressors or vulnerabilities are sensitive to factors within the control of the resilience team.

The resilience agenda-setting exercise works best when undertaken collaboratively within the context of a resilience team. Each entity in the resilience team should select and score potential disrupting factors individually, then converge on network-level scores and priorities by convening with other team members in a workshop or series of meetings where partners can compare scores for top-ranked issues. Setting a resilience agenda may be scoped into an MPO or statewide freight plan, a corridor study, a resilience plan, or a special standalone study undertaken by a resilience team. To streamline the process, a resilience team may wish to have each entity select only the stressors from Figure 21 that are of greatest concern to their organization and then work from that subset when setting the resilience agenda. This enables a resilience team to move from chasing concerns about a seemingly infinite number of possible individual disruption events to pinpointing broad and addressable causal vulnerabilities facing a network ecosystem.

Figure 24 offers a simple points-based system to index and score the relative position that potential shocks and stresses may have on the resilience agenda. Figure 25 introduces a holistic

scoresheet by which the resilience team can profile its agenda within the broad range of shocks and stresses to be addressed through a resilience program.

When using this scoring approach, resilience teams assign a score ranging from zero to 15 to each disruption stressor listed in Figure 21, with stressors assigned 15 points understood to be at the top of the resilience agenda. Some principles to consider in scoring and prioritizing factors for the resilience agenda are as follows:

Customize the List of Stress Factors: The stress factors listed in Figure 21 are a suggested starting point for resilience teams because they provide an opportunity to consider the entire resilience ecosystem. However, a resilience team may wish to add factors to the list at the outset or limit the agenda-setting to a subset of the factors. The value of starting with the stress factors listed in Figure 21 is that the team can make a conscious choice about what to consider and what not to consider based on the multiple dimensions of network resilience.

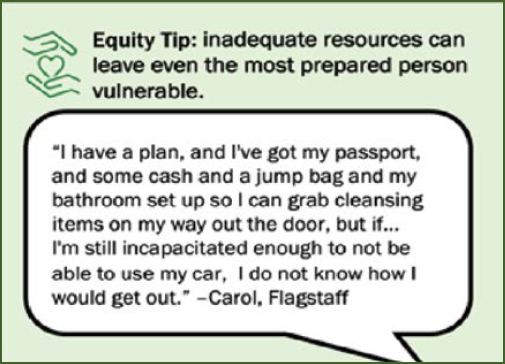

Consider Stress Factors from the Perspective of Noninstitutional Stakeholders: Play 2 addresses the importance of including noninstitutional stakeholders in the network resilience planning team. When

arriving at score #2 in Figure 24, a resilience team can identify needs by considering how potential stress factors may affect lower-income households or small businesses with few resources. The observation shown to the right is based on dialogue between the Flagstaff MPO and a disabled resident during the 2022 wildfires. Appendix E provides further detail about the Flagstaff experience and involving social equity communities “in their own words.”

Eliminate Stress Factors with Any Zero Scores: Before adding the scores together to get the composite score for any given stress factor, eliminate any stress factors that received a score of zero. If the resilience team concludes that a factor either (1) has no possibility of causing a disruption, (2) any disruption would be without impact, or (3) there is no possible leverage the team can have on the stress factor, it does not matter what the other two scores are. Effectively, a single zero score for any factor eliminates it from the scope of the resilience agenda.

Weight All Three Scores Equally: Each of the three scores can range from zero to five. Equal weighting ensures that the team is not distracted from long-term priorities by recent events or outside agendas. For example, if a new weapon is created and captures headlines for the profound impacts it can have on transportation networks, a resilience team could be pressured to immediately focus its resources on the extremely high-impact event that the weapon could create. However, by weighting the factors equally, the team may be able to temper the strong political concern about the new weapon with pragmatic considerations of how likely the weapon is to be used and whether there are responses that can realistically be implemented by the team.

Do Not Underestimate Factors with a Single Point of Leverage: For the leverage score (score #3), it should be noted that, even if a singular entity on the resilience team has leverage over a stressor, there is some basis for including it in the resilience agenda. This may appear to go against the principle that network planning is intended to focus on issues that are beyond the purview of any single entity. However, even when stressors fall under the control of a single entity, other entities on the team may inform the controlling entity’s responses or preparations for the potential disruption as well as provide a more holistic understanding of options for the controlling entity.

Apply Collective Judgment: The purpose of the scoring exercise in Figure 24 and the ranking sheet in Figure 25 is to facilitate a rigorous and holistic consideration of options and needs and frame network disruptions for a resilience team. At the outset of the exercise, teams may alter the scoring basis or the universe of stress factors. Teams may also choose to set the agenda based on the factors with the highest overall scores or those with the highest scores in each of the four stress categories shown in Figure 25. The agenda should always reflect the judgment of the resilience team.

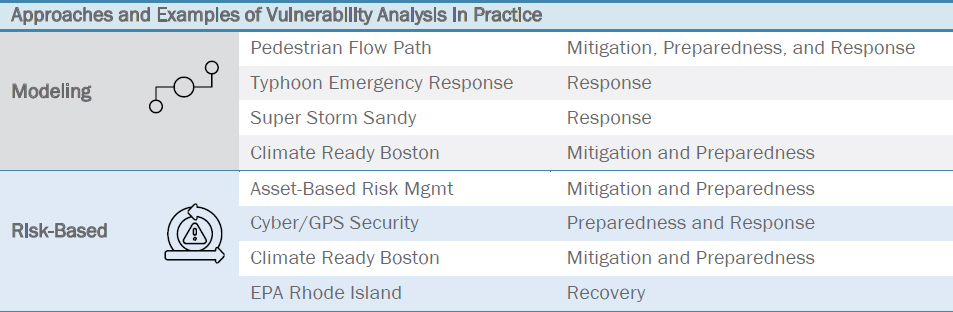

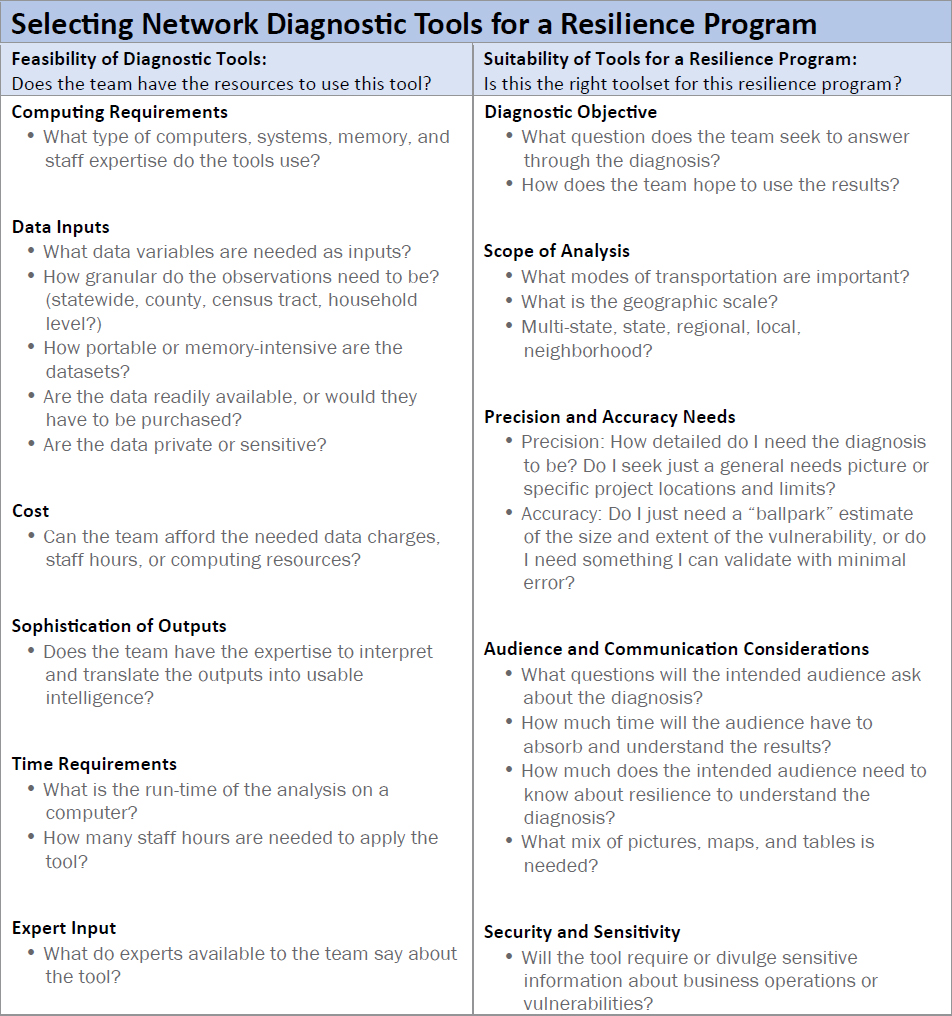

Apply Diagnostic Tools to Identify Specific Project Needs

To move from setting a resilience agenda aimed at identifying categorical stress factors and potential disruptions to deploying a specific program of assets, systems, and projects, the team can select from a wide and growing range of diagnostic tools. Diagnostic tools for resilience (1) apply available data and assumptions about the network and its components; (2) incorporate parameters by which the resilience team defines needs or emphasis areas for the program (based on the self-assessments in the plays given); and (3) provide outputs such as maps, tables, and lists of potential specific infrastructure components for improvement as part of the resilience program.

Available tools include (1) new tools developed expressly for this playbook to compare cascading effects of disruptions on specific facilities as shown in NCHRP Web-Only Document 391, Volume 2, Sections 3–6, and network-robustness modeling as shown in Section 7, as well as (2) a growing menu of existing and emerging diagnostic tools provided in the resilience toolkit published in NCHRP Web-Only Document 391, Volume 2. Diagnostic models can provide meaningfully different assessments of potential resilience projects. Figure 26 offers considerations for selecting a set of diagnostic tools in a resilience program (for a more detailed discussion, see Appendix B).

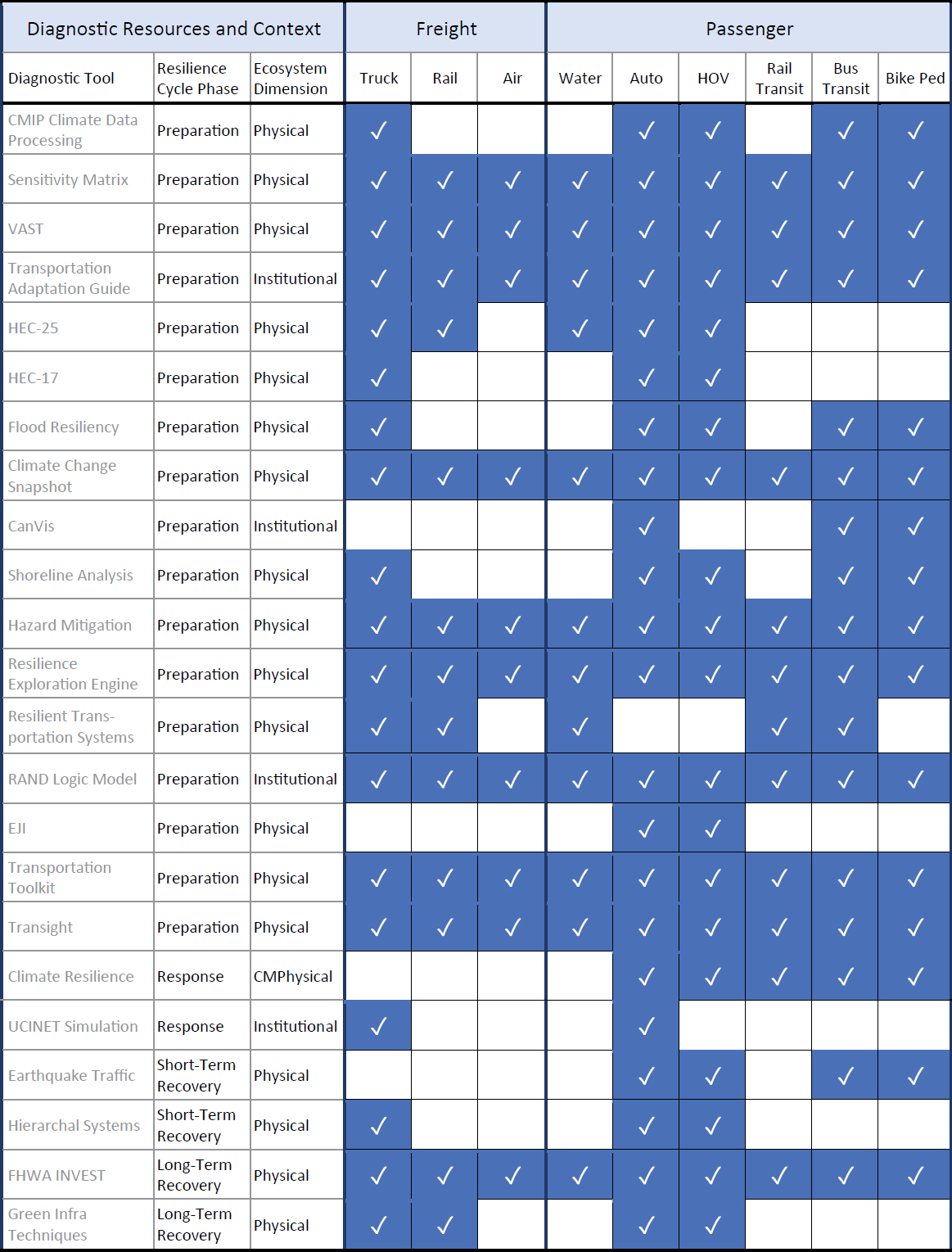

Figure 27 offers a menu of available tools by which practitioners can select tools aimed at specific types of vulnerabilities and aspects of the resilience ecosystem at each juncture of the resilience cycle. Each tool can be further explored in NCHRP Web-Only Document 391, Volume 2, Section 1, with its source, associated data inputs, outputs, and key steps for assessing supply-chain and economic vulnerabilities. Most of the diagnostic tools created to date address the physical dimension of the resilience ecosystem and are applied during the preparedness phase

Figure 27. Resilience tool distribution by cycle phase and ecosystem dimension.

of the resilience cycle. Of the tools identified in Section 1, 20 of them address the physical aspects of the resilience ecosystem, five address the institutional, and three address the individual level. There are 20 methods/tools offered that address the preparation phase, two that address the response phase, two that address short-term recovery, and four that address long-term recovery.

When selecting diagnostic tools for a resilience program, it can be helpful to consider the role that diagnostic tools have played in preparing for, responding to, and recovering from disruptions in different contexts. Figure 28 provides a directory of the case studies available in NCHRP Web-Only Document 391, Volume 1, that describes how agencies and resilience teams have used diagnostic and risk-based analysis tools to navigate preparation for, response to, and recovery from network disruptions in diverse contexts.