Incorporating Resilience into Transportation Networks (2024)

Chapter: Appendix E: "In Their Own Words" Social Equity Case Study (Flagstaff)

E.1 Rationale for “In Their Own Words” Inclusion of Noninstitutional Stakeholders

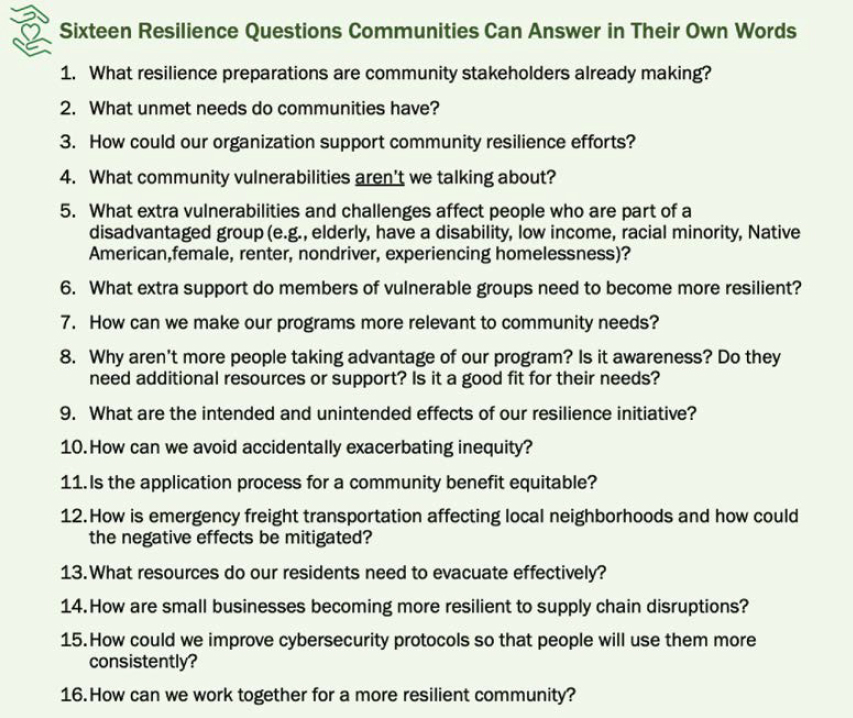

Identifying and consulting community stakeholders is a core component of an effective, equitable resilience-planning process. Doing so is an opportunity to identify untapped community resources and proactively identify vulnerabilities that may be overlooked during technical planning exercises. In the long term, resilience-planning processes are strengthened when they include institutionalized mechanisms for ongoing community partnerships.

A good first step is to learn about community needs directly from community stakeholders in their own words. This approach provides immediate data on current community challenges and strengths while also building relationships and laying the groundwork for future cooperation.

The two most viable options for learning about community stakeholder perspectives in their own words are focus groups and one-on-one interviews. Surveys are sometimes used for stakeholder consultation, but their rigidity and reduced detail make them less useful for understanding community perspectives holistically and for detecting the “unknown unknowns” that can be revealed through interviews and focus groups.

Generally speaking, individual interviews are an underutilized tool in resilience planning and should be deployed more broadly. As compared to a survey, interviews provide more in-depth information on people’s experiences and self-identified needs. Interviews are also well suited for rapidly changing situations such as the disaster response and recovery stages, as the questioning strategy is more flexible than a survey in which all respondents must be asked the same questions in the same way, regardless of how local conditions may be changing. Interviews with stakeholders who have not been included in the broader resilience-planning progress are also critical for identifying elements that may have been missing from the planning discussion, with or without plans to bring community members directly into planning conversations.

For this reason, an interview project is also a good rapid-response technique to get immediate data on a crisis or rapidly changing situation. A project of six to ten interviews can be launched much more quickly than any survey and without the extensive pre-research needed to select appropriate survey items. A project like this excels at quickly identifying potential problems, vulnerabilities, and strengths that should receive more detailed follow-up attention. The Flagstaff project, for example, found that some nondriving residents have no identified way to evacuate in case of a wildfire. This concerning finding indicates a need for a more detailed follow-up to find out how widespread the problem is, and the interviews identified specific gaps and promising options to be explored. The project also connected local planners with nondriving residents who were willing to answer additional questions.

One-on-one interviews also have advantages over more commonly used focus groups. As compared to a traditional focus group, individual interviews give a clearer picture of variations between people and are well suited for identifying vulnerabilities that disproportionately affect some communities more than others. Additionally, from a pragmatic standpoint, vulnerable stakeholders tend to be difficult to schedule and may lack transportation or the technological capabilities to participate in an online event. It is much easier to get six thoughtfully selected interview participants to talk with you one-on-one than it is to get them to talk with you all at the same time.

E.2 Observations of “In Their Own Words” Outreach Following Flagstaff Wildfires, June and July 2022

Context: Flagstaff, Arizona, has been experiencing an increasing number of wildfires and related post-wildfire flooding. These disasters sometimes result in major highway closures, with few alternative routes available. In summer 2022, Flagstaff was affected by the Pipeline and Tunnel

fires. To better manage resilience, the Flagstaff Metropolitan Planning Organization (FMPO) wanted to use the recent disasters as an opportunity to identify current community needs and risk factors as well as to reflect on ways to increase community resilience before the next disaster. One-on-one interviews with community stakeholders were used to improve understanding of community stakeholders’ perspectives in their own words.

Approach: Potentially vulnerable groups were identified about whom FMPO had inadequate data. FMPO was particularly interested in the effects of the fires on the region’s Navajo community, many of whom travel frequently across the routes closed by fires and fire-related flooding. Additionally, planners thought it would be valuable to assess evacuation readiness among Flagstaff’s nondriving residents, whether nondriving by circumstance or car-free by choice.

With support from a qualitative research specialist, six community stakeholders representing populations of interest were interviewed about the effects of the most recent wildfires as well as their needs and suggestions for preparing for future disasters.

Potential participants were identified through the city of Flagstaff’s community forum, an online forum for civic engagement with more than 3,000 registered users. Participants were screened based on membership in populations of interest. Backup recruiting strategies were identified in case certain populations could not be found among the applicants from the forum post, but these backup avenues were not needed. Twenty residents volunteered to be interviewed about the effects of the fire on their travel, health, or job. Six candidates were selected who represented the populations of interest. Participants were interviewed via Zoom and given a gift of a $25 Visa card to thank them for their time.

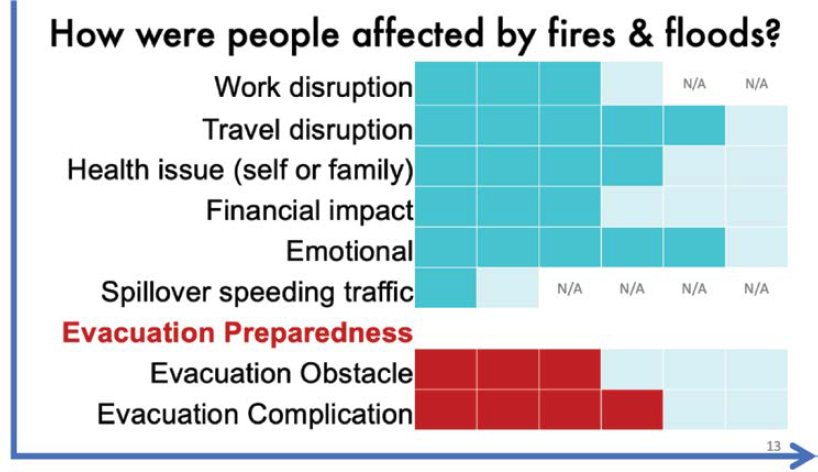

Findings: All respondents were affected by wildfires to greater and lesser degrees. The consequences of those disasters were determined not just by the events themselves, but by people’s pre-existing strengths and vulnerabilities, and the resources they had to use to cope with the consequences (see Figure E.1).

The project documented that the effects of travel disruptions were more severe on vulnerable groups. For example, while salaried white-collar workers experiencing a work travel disruption did not report losing income, low-income service workers were vulnerable to income loss.

FMPO’s guess that Navajo residents might be experiencing additional effects was shown to be correct; the normally 90-minute trip from Tuba City on the Navajo-Hopi reservation to Flagstaff, where many Navajo Nation members go to work, access healthcare, or visit family, doubled in length or became impossible.

Evacuation preparedness among vulnerable populations was also found to be worse than expected. As one nondriving resident put it, “I have a plan, and I’ve got my passport and some cash and a jump bag and my bathroom set up so I can grab cleansing items on my way out the door, but I do not know how I would get out of here.”

In addition to vulnerabilities, the project uncovered community goals, skills, and resources that could be used for future resilience projects. A soil scientist signed up for the interviews in part because he hoped that the city would take advantage of his agency’s floodwater-mitigation services. One participant suggested a community fire council, and several participants displayed skills that would be valuable to such an effort should FMPO or another Flagstaff organization decide to pursue a project in that vein.

For FMPO, the project “gave a very real face” to community needs and the effects of FMPO’s decisions. It replaced FMPO’s hunches about community needs with data. By identifying the unanticipated vulnerability of nondriving residents before it became a crisis, the project gave FMPO more tools to proactively plan for resilience. Additionally, FMPO made connections with community stakeholders. All interview participants chose to be available for follow-up questions as FMPO’s resilience planning moves forward. Leads were identified to work with a local stormwater mitigation organization and to connect with Flagstaff’s homeless community, who live in the wildfire-vulnerable national forest. Participants reacted to the experience positively. As one said, “There’s really been no one to speak to about this. So, them doing this kind of outreach? Let them know that I appreciate it.”

E.3 Lessons Learned and Further Applications of Social Equity in Network Resilience/Disruption Response

Interviewing community stakeholders in their own words is a low-cost way to learn about community stakeholders’ perspectives and needs, as well as to form relationships that can be drawn on for future community consultation. A larger project interviewing more respondents can provide a fuller panorama of community perspectives and power to compare between groups. However, as the Flagstaff project shows, even a small project with strategically selected interview respondents can provide valuable information and provide guidance on information that is still needed.

The community interview model demonstrated in Flagstaff can be applied to a wide variety of resilience scenarios.

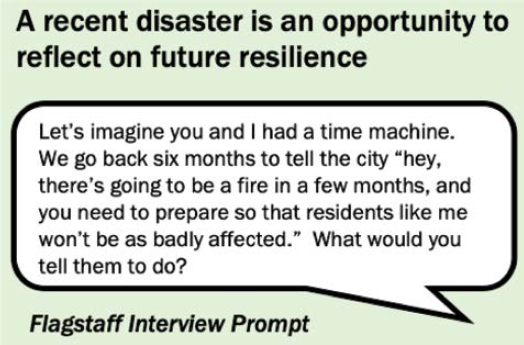

Interviewing community stakeholders during the disaster response and recovery phase proved to be a good opportunity to encourage participants to reflect on longer-term resilience issues. The strategy that worked especially well was asking participants what measures they wished had been in place before the recent disaster.

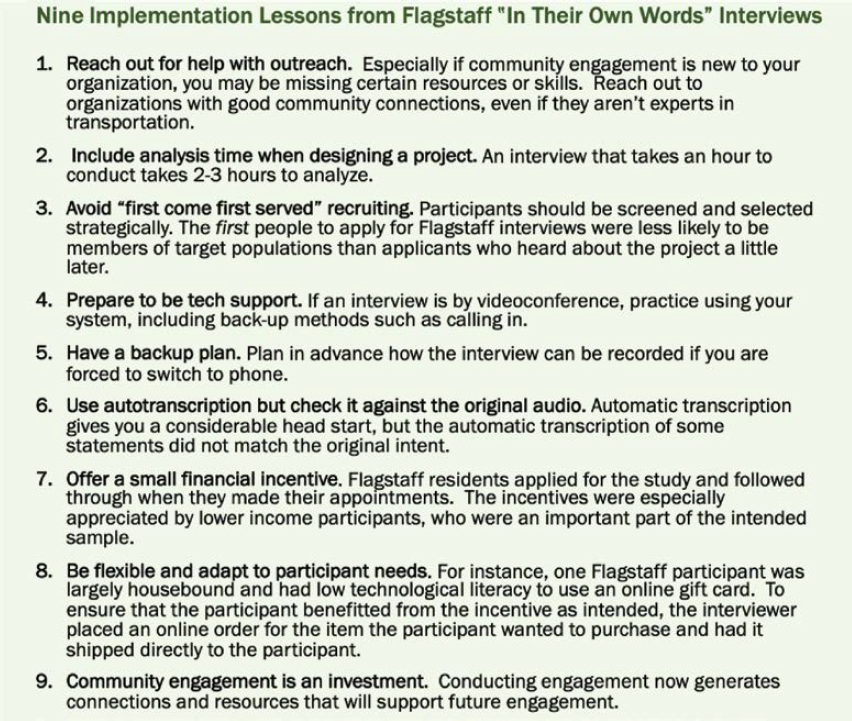

The Flagstaff project also showed the value of longer-term investment in community contacts. The study effectively used the community engagement portal run by the city of Flagstaff to identify interview participants within just a few days. Organizations without a history of engaging community stakeholders should contact local

government and nonprofit organizations that may have pre-existing community connections. This technique is valuable whether or not the organization’s mission includes transportation; the most important factor is their relationship with community members.

E.4 Implementation Guide

This section uses materials from the Flagstaff project to provide an implementation guide and templates that resilience planners in other cities could use to complete a similar project. A key facet of these interviews is that they were designed to learn from the community, rather than to educate. The interviewer was not evaluating community respondents’ ideas but documenting them for later analysis.

The following table contains an annotated version of the interview guide used in Flagstaff. It can be used in or adapted for other communities. From a technical standpoint, the study used a primarily semi-structured protocol that borrows some elements from unstructured (flexible) interviewing. Most questions are scripted. However, some of the more important questions, such as “How have the wildfires affected you?”, follow an unstructured format where the interviewer follows up only with topics that did not arise naturally. This hybrid structure results in a more efficient and conversational interview.

Example Community Resilience Interview Guide (60-minute interview)

Part 1: General and Background

- How do you usually travel around your community?

If not addressed: Do you own a car? Do you use transit? Walk? Bike? Carpool? Ride-hailing services/taxis?* - Do you have a disability or a health condition that makes it harder for you to travel?

- Do you have a respiratory illness such as asthma?

- From your perspective, what are the main problems with transportation in your community?

- What would you like to see changed about transportation in your community?

Part 2: Wildfire Effects

- How have the recent wildfires and flooding affected you?†

Follow-up topics (if not already addressed):- Road closures (as a travel disruption, accessibility, community connection)

- Evacuation

- Transit service disruptions

- Other mobility impacts

- Economic (e.g., income, business, damage to home)

- Social (including canceled plans, difficulty accessing relatives)

- Health: direct (e.g., air quality) and indirect (e.g., interrupted treatment access)

- Resources that would help them recover

- Let’s imagine you and I had a time machine. We go back six months to tell the city “Hey, there’s going to be a fire in a few months, and you need to prepare so that residents like me won’t be as badly affected.” What would you tell them to do?§

Part 3: Evacuation Preparedness

- Have you ever evacuated from a wildfire? What was that like?

- If you had to evacuate now, what would you do? Follow up as necessary with:

- What kind of transportation would you use?

For nondrivers/carless respondents: Do you know of anyone who would be able to offer you a ride? How confident are you that you would have a way to get out? - Where would you go? Would this affect your decision about whether or not to evacuate?

- What kind of transportation would you use?

- Is there anyone else you would need to take with you? Including people who don’t live with you?

Do you know if any of your neighbors don’t have cars?¶ - How would you decide if it’s time to evacuate from a wildfire?#

- Let’s get in our time machine and go back six months again. What would you tell the city to do to help people get prepared to evacuate?

Part 4: Demographics and Closing

- Collect demographic information: age, race/ethnicity, gender, household size, and income.

- Thank you for all of this. It’s been really helpful. Is there anything else you think I should know?

- When I share what I learned from our conversation with [organization or “my colleagues”], would you like me to also share your contact information in case they have follow-up questions? This is totally optional.

Thanks again for your time! This has been really helpful.

*Text in italics is not designed to be read aloud. It contains instructions for interviewers and example follow-up prompts to be used if needed.

†This is an example hybrid semi-structured/unstructured question format. It results in a more natural conversation than asking about each effect individually. Interviewers will only follow up on topics that were not covered. The follow-ups are listed as topics rather than fully scripted to be more flexible and to keep the interview guide legible.

‡Asking about family/friends is a common interview technique for informally extending the sample size.

§This “time machine” question makes an interview about a recent disaster an effective tool for engaging respondents in a conversation about long-term resilience.

¶Most respondents will interpret this question in context as being about whether or not their carless neighbors will need help evacuating. If not, follow up by asking directly whether the respondent believes their neighbors have a way to evacuate.

#This prompt can lead to a discussion of information sources, how they determine when something is “bad” enough to leave, and/or the obstacles that might prevent them from leaving.

Interviews were conducted via an online video-conferencing service. Automatic transcription was used and checked manually for accuracy. The open-ended interview relies on nondirective probing to get detailed information out of respondents while directing the conversation as little as necessary. Aspiring interviewers may wish to read Robert Weiss’s guide to Learning from Strangers to improve their interviewing techniques.84

Interviews produce a wealth of information, both in quality and quantity. A typical one-hour interview transcript can run 10 to 15 pages per interview. A key challenge of data analysis is distilling that information to uncover the patterns in it.

Two common techniques for analyzing qualitative data are coding and analytic memoing. Coding is a strategy for identifying patterns by labeling and categorizing interview responses. It is used alongside analytic writing and is typically completed using specialized software such as NVivo, MaxQDA, AtlasTI, and Dedoose. Dedoose, which uses a monthly subscription service, may be more accessible to new users.

However, particularly for a smaller project, coding may not be the most efficient way to identify patterns. This is especially true if the researcher does not already know how to use a qualitative coding platform. Instead, a sequential analytic memo process is recommended. The analyst starts with the interview transcript, creates an individual memo distilling key findings of each interview, and then uses comparative matrices to identify overall patterns. At each stage, the analyst starts by describing the interview contents before moving into identifying significance, editorializing, or comparing to other interviews.

When evaluating the conclusions drawn from analyzing interview responses or if the meaning of something is ambiguous, it is helpful to conduct member checks by checking in with one or more interview participants to see if they agree with the interviewer’s interpretation of their words.85

When presenting findings of interviews, it is considered a best practice to provide transparency and context by including direct quotations and excerpts of interviews.85 Presenting participants’ perspectives in their own words illustrates findings more clearly and preserves context and nuance. Showing the audience “source material” also allows the audience the chance to evaluate the interviewer’s interpretation of responses.