On Leading a Lab: Strengthening Scientific Leadership in Responsible Research: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 3 Gaps in Traditional Approaches to Professional Development

3

Gaps in Traditional Approaches to Professional Development

The second session, moderated by planning committee member Robin Broughton, Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI), was designed to explore the skills and capacities that research leaders need to foster responsible research in their labs, centers, and collaborations, and to identify current approaches and the gaps between what is needed and what is provided.

In her opening remarks, Broughton noted that HHMI, through the Center for the Advancement of Science Leadership and Culture, is involved in efforts aimed at developing professional development resources for scientists that can support them in advancing healthy, effective collaborations, training practices, and lab workspaces. HHMI also collaborates with other organizations with expertise in principled leadership and effective mentorship.

In addition to addressing needed leadership approaches and gaps, Broughton also asked the presenters to consider the risks to the research enterprise if these gaps are not addressed. The presenters were Michael O’Rourke, Michigan State University; Tristan McIntosh, Washington University in St. Louis; and Catherine Lyall, University of Edinburgh.

TRAINING FOR CROSS-DISCIPLINARY COLLABORATIVE RESEARCH

O’Rourke highlighted a gap in training provided to students and other early-career scientists who are engaged in cross-disciplinary team science.

While labs are great ways to acquire experience, learn to work with others on experiments, co-present, and co-author, the training is disciplinary in the fashion of that lab. Training does not typically involve cross-disciplinary research, although it is becoming an increasingly prominent part of funding portfolios. Early-career researchers have a long future ahead of them, and they have the right to expect training in this complex research landscape, he stated. The National Science Foundation (NSF) and a few others support training in the conduct of cross-disciplinary research, but he said the combination of training in collaborative and cross-disciplinary research is necessary.

The long-standing way to become cross-disciplinary is for researchers to build disciplinary depth before cross-disciplinary breadth; working across disciplines is not part of their formal training. As a consequence, he said, researchers join cross-disciplinary teams unprepared to communicate with collaborators from other disciplines or to build the common ground for substantial integration of disciplinary perspectives. O’Rourke identified two challenges: the Problem of Unacknowledged Differences and the “Captain Obvious Problem.” In the first case, researchers walk into a situation as disciplinary experts to collaborate with others who they know have different expertise, but they do not recognize how their expertise differs from others to address the complex problems. Efforts to address this issue lead to the “Captain Obvious Problem.” Researchers do not need to be experts in each other’s domains, but they do need to know foundational aspects of others’ perspectives. However, the core beliefs and values that ground a researcher’s perspective will seem obvious to them, and they will be disinclined to talk about them because no one wants to become known as the collaborator who talks about obvious things. This disincentive gets in the way of the communication needed for efficient and effective collaboration, he said.

The gap between traditional disciplinary training and collaborative cross-disciplinary training, which affects researchers at all career stages, can be addressed through new leadership approaches, O’Rourke continued. He noted research leaders are in the best position to identify, prioritize, and act to provide cross-disciplinary training through both formal and informal interventions to improve knowledge integration. Research suggests that interventions can help build collaborative capacity and improve research outcomes (Shuffler et al., 2011; Okhuysen and Eisenhardt, 2022). Funders, including NSF and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), recognize the need for this type of training to increase the return on investment in team science. One prominent example is NSF’s Convergence

Accelerator. Funded teams must participate in an 18-week curriculum. O’Rourke is part of the faculty that provides training in cross-disciplinary communication, conflict management, building trust and psychological safety, and developing a mutual learning mindset. He also said these issues are addressed by the Toolbox Dialogue Initiative (TDI), an NSF-supported project that facilitates collaborative capacity with partners around the world and investigates the practice of collaborative, cross-disciplinary research.1

Two risks stand out if training in collaborative, cross-disciplinary research is not provided, in O’Rourke’s view. First, as mentioned, is the failure as mentors and educators to meet the responsibilities of providing the next generation with the skills to succeed in cross-disciplinary research environments. Second, if that happens, the broader public will not have the experts needed to address urgent societal problems. Training in this type of research modality is needed to create and support responsible researchers, now and into the future. He urged training in collaborative cross-disciplinary science as part of responsible conduct of research (RCR) training to create conditions for growth and excellence. Training people to be responsible collaborators on complex research teams helps them avoid epistemic injustices such as disciplinary chauvinism and epistemic exclusion while exhibiting virtue in their research collaborations, he concluded.

LEADING, MENTORING, AND MANAGING FOR RESEARCH EXCELLENCE

McIntosh focused on essential skills to lead and manage research teams for scientific excellence. She draws on training as an industrial organizational psychologist who studies people and processes in the research workplace, which she said applies to ethical and professional issues that arise in science and medicine.

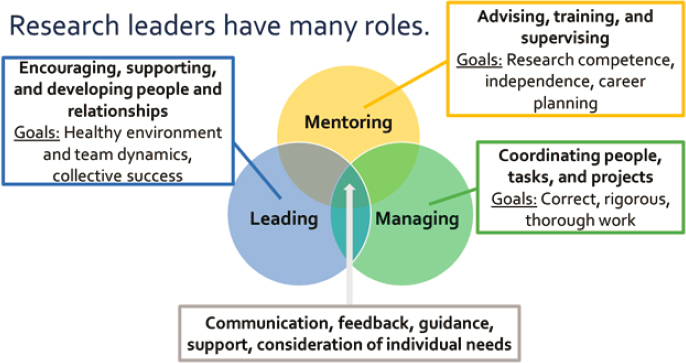

Research leaders have many overlapping roles beyond their scientific responsibilities. Their roles to lead, mentor, and manage have both commonalities and differences (Figure 3-1). Leading involves encouraging, supporting, and developing people and relationships for collective success. Mentoring involves advising and training mentees to build research competence, independence, and careers. Managing involves coordinating people, tasks, and projects to achieve correct, rigorous, and thorough work. All three roles are supported by skills and practices such as communication, feedback,

___________________

1 For more information on TDI, see Hubbs et al. (2020) and https://tdi.msu.edu/.

SOURCE: Tristan McIntosh Workshop Presentation, December 4, 2023. Graphic by Alison Antes and Tristan McIntosh.

guidance, support, and consideration of individual needs, but leaders are not typically taught these skills in their formal scientific training.

To address these professional development needs, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has funded the Compass project for biomedical junior faculty and postdocs, which is directed by Alison Antes and co-directed by McIntosh.2 Through remote training and mentoring, participants learn essential practices to lead and manage research. Three cohorts have participated since 2022, and one is scheduled for January 2024. She noted Compass draws from their team’s collective work of over 75 papers to build an evidence base, including on the topics of RCR, root causes of research wrongdoing, exemplary research leadership, and researcher training and development.3 In-depth interviews have been conducted with research exemplars, in which a top theme expressed is the importance of building quality relationships with each person on a team (Antes, Mart, and DuBois, 2016; Antes, Kuykendall, and DuBois, 2019). A forthcoming publication from Antes and McIntosh shows indications that focus groups with early-career researchers reinforced that they feel they need to learn how to

___________________

2 For more information, see https://researchercompass.org/.

3 For more information, see papers authored by McIntosh, Antes, DuBois, and others in the references section of this chapter.

lead teams and create good team dynamics, especially when members have different roles, career stages, personalities, and other variables.

The team’s survey of NIH-funded postdocs about the behaviors of the principal investigators (PIs) with whom they worked showed a positive association of relationship-oriented behaviors, perceptions of lab ethicality, and job satisfaction with productivity (Antes et al., 2024).4 Moreover, in a national survey about the root causes of research integrity violations, 93 percent said inadequate supervision is a common cause (in interviews with institutional officials this figure was 77 percent), which she said calls for better management and oversight.

Compass focuses on fostering discovery and impact; rigor, responsibility, and transparency; RCR; diversity, equity, and inclusion; and mentoring. Organizational and leadership literature was reviewed to identify best practices related to three domains of best practices: (1) leading others, (2) managing scientific work, and (3) leading oneself.

In the first domain, leading others, the project identifies six areas of best practices: cultivate a positive work environment, build relationships, strive to understand others’ perspectives, encourage team engagement, resolve conflict, and model the way. In the second domain of managing scientific work, best practices are to set and align expectations, establish operational procedures, manage the data lifecycle, provide formal training, hold effective meetings, and provide feedback and guidance. The domain of leading self assumes that a person cannot effectively lead and manage a team without some degree of self-awareness. Best practices are to use professional decision-making strategies; reflect, experiment, and adapt to understand one’s own strengths and limitations; cultivate a network with multiple mentors; prioritize needs and be able to communicate those needs; manage personal well-being; and be strategic and intentional. McIntosh pointed out that the three domains—leading others, managing the scientific work, and leading self—work in tandem to create an environment and strengthen interpersonal dynamics.

LEADING AN INTERDISCIPLINARY LAB: IMPLICATIONS FOR CAREERS

Lyall offered a European and United Kingdom perspective about the skills needed to lead interdisciplinary labs and the implications for

___________________

4 For more information, see https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/jmxrw.

early-career researchers (ECRs). To provide a point of reference, she cited the definition of interdisciplinary research (IDR) from a National Academies report on the topic (NAS, NAE, and IOM, 2005):

A mode of research by teams or individuals that integrates information, data, techniques, tools, perspectives, concepts, and/or theories from two or more disciplines … to advance fundamental understanding or to solve problems whose solutions are beyond the scope of a single discipline or area of research practice.

She became interested in the topic as an object of scholarship based on her own experiences as an early-career research fellow (Lyall, 2019; Lyall et al., 2015). She echoed previous comments that interdisciplinary research is altering the research landscape. As the former European Commissioner for Research, Science, and Innovation, Carlos Moedas said, “The most exciting and groundbreaking innovations are happening at the intersection of disciplines.”

However, Lyall continued, a paradox holds true in which IDR is promoted at the policy level in response to societal challenges while poorly encouraged or rewarded at the institutional level (Weingart, 2000). ECRs receive mixed messages about whether they should engage in interdisciplinary research if they want to further their careers. In interviews, researchers involved in IDR reported they are expected to be trained in a discipline, be able to work in an interdisciplinary environment, but then go back to their own discipline.

In the context of RCR, she argued that tempting anyone into an interdisciplinary career without providing an adequate safety net is at best ironic, if not hypocritical and possibly unethical. Research leaders must ensure that ECRs are given the best circumstances to thrive. Regretfully, they may not always be well served by focusing on interdisciplinary work at this stage of their careers. Affiliation with an interdisciplinary research center has been shown to be more detrimental to junior than senior staff (Sabharwal and Hu, 2013); it can take them longer to be tenured. She labeled it a high-risk, high-reward endeavor in which they may become prominent but less productive in terms of publications and other measures (Leahey et al., 2017). She continued that British interdisciplinary academics have noted the difficulty in obtaining follow-on funding across their academic life. There are enduring challenges in the review process that is still built on specific disciplines. She urged recognition of these career implications, the need for

promotion and reward structures to recognize these different patterns, and the need for role models, mentors, and champions.

Turning to resources, Lyall described the European Union-funded SHAPE-ID (Shaping Interdisciplinary Practices in Europe) project led by Trinity College Dublin in Ireland. The SHAPE-ID project has a web-based toolkit that leads to a myriad of resources to strengthen career pathways in interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research.5 There are resources on career development and how to support those seeking an interdisciplinary career, as well as downloadable guides on such topics as mentoring. Another UK resource is the Concordat to Support the Career Development of Researchers, although she pointed out that it does not mention interdisciplinarity. The UK Vitae and Researcher Development Framework is similar to Compass, as described by McIntosh above, but she said it has not been uniformly implemented. She also noted the Future Leaders Fellows Development Network and a forthcoming handbook for ECRs developed by the Global Alliance for Inter- and Transdisciplinarity.6 Finally, she suggested the recently published anthology Foundations of Interdisciplinary and Transdisciplinary Research (Vienni-Baptista et al., 2023).

“If we think of responsible research as the prevention of transgressions, we are in danger of transgressing against early-career researchers,” she concluded. “We are encouraging them to work in an interdisciplinary way, but we are not necessarily providing them with the tools and the leadership to thrive.”

DISCUSSION

Broughton commented that the different tools described by the presenters show that people are interested in information for researchers interested in IDR. Noting the resources are locally or externally funded, she asked about a role for the National Academies and other organizations to shift to a paradigm in which institutions engage in this work and not perceive it as a distraction from “real research.” Lyall concurred that there are many support mechanisms, but they are frequently voluntary, grant-funded,

___________________

5 To access the SHAPE-ID toolkit, see https://shapeidtoolkit.eu.

6 For information on the Concordat, see https://researcherdevelopmentconcordat.ac.uk/. For information on the UK Vitae Framework, see https://www.vitae.ac.uk/researchers-professional-development/about-the-vitae-researcher-development-framework. For information on the Future Leaders Network, see https://www.flfdevnet.com/. For information on the Global Alliance, see https://itd-alliance.org/.

and time-limited. As an example, the SHAPE-ID Toolkit funding ended, although it was designed with legacy in mind. In the United Kingdom, the Wellcome Trust and others have looked at how to embed IDR culture within universities. The next iteration of the Research Excellence Framework (REF), which is a performance measure used to assess the quality of research across UK higher education institutions, will place more emphasis on the research environment and not just its outputs. This may be a significant driver for universities to take RCR issues more seriously because funding will depend on it, she posited. McIntosh agreed with the importance of institutional environment. She suggested helping institutions understand that “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure,” and norms, policies, and messaging from leadership that are in alignment with RCR can improve institutions’ bottom line. O’Rourke underscored the value of a curated set of resources that can make it more efficient for researchers to find what they need. He also reflected that curation is a sign that the field of the science of team science is recognizing the need to be evidence-based.

Susan Wolf, University of Minnesota, asked about the challenge of research leadership to reconcile differences in transdisciplinary and interdisciplinary research, for example substantive differences across disciplines related to authorship conventions, record keeping, data management and sharing, and ethics. Lyall noted SHAPE-ID has guides and tools to build collaborations across different disciplinary traditions. A book co-edited by O’Rourke titled Interdisciplinary and Transdisciplinary Failures (Fam and O’Rourke, 2021) also has useful lessons, she commented. One lesson provided by Lyall is the need to take time at the beginning of a collaboration to discuss differences in authorship guidelines among members and to revisit the issue throughout the collaboration. O’Rourke emphasized the need to be transparent and explicit about all expectations through structured dialogue, collaboration agreements, and other approaches.

A participant asked about changes in the curriculum to deal with the perception that researchers who cross disciplines are not “real researchers.” She also observed that many fields, especially in the humanities, have classes for graduate students on how to conduct research while, in her experience, graduate engineering disciplines do not. O’Rourke responded that this gets to the heart of a challenge in which researchers have many demands to fulfill in limited time. He pointed to the curriculum that is part of the NSF Convergence Accelerator as one way to champion and motivate this activity. It took a few years of funding before word got out about the requirement. Now people who come into the program expect it and recognize it can be

valuable for their teams. It is a top-down approach but given the concerns, this may be needed in some cases, he said.

Kara Hall, National Cancer Institute within NIH, shared a comment from a PI involved in a large NIH-funded transdisciplinary center who asked whether he was now “expected to be a generalist.” She clarified that the need is to learn the basic tenets of other disciplines to do this type of highly integrative work. She added that by the end of the five years, he and others were strong proponents of transdisciplinary research. Gregory Weiss, University of California, Irvine, commented that some behaviors that are not amenable to training programs—such as compassion, inclusivity, and mindfulness—are important to the current generation of students. Senior investigators have to make them part of the culture. Moreover, he posited, every 10 years, a new set of ideas and values challenges the scientific community.

France Córdova, Science Philanthropy Alliance, ended the morning session by commenting, on behalf of the Strategic Council, on the value of the presentations and dialogue as a demonstration of the importance of the issue. She reflected on how things have changed since earlier in her career and said she valued the opportunity to learn about new ways of leading.

REFERENCES

Antes, A., English, T., Solomon, E. D., Wroblewski, M., McIntosh, T., Stenmark, C. K., and DuBois, J. M. (2024). Leadership, management, and team practices in research: Development and validation of two measures. [Preprint available on PsyArXiv]. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/jmxrw.

Antes, A. L., Kuykendall, A., and DuBois, J. M. (2019). Leading for research excellence and integrity: A qualitative investigation of the relationship-building practices of exemplary principal investigators. Accountability in Research, 26(3): 198–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2019.1611429.

Antes, A. L., Mart, A., and DuBois, J. M. (2016). Are leadership and management essential for good research? An interview study of genetic researchers. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 11(5): 408–423. https://doi.org/10.1177/1556264616668775.

DuBois, J. M., and Antes, A. L. (2018). Five dimensions of research ethics: A stakeholder framework for creating a climate of research integrity. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 93(4): 550–555. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001966.

DuBois, J. M., Chibnall, J. T., Tait, R., and Vander Wal, J. (2016). Misconduct: Lessons from researcher rehab. Nature, 534(7606): 173–175. https://doi.org/10.1038/534173a.

DuBois, J. M., Chibnall, J. T., Tait, R., and Vander Wal, J. S. (2018). The Professionalism and Integrity in Research Program: Description and preliminary outcomes. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 93(4): 586–592. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001804.

DuBois, J. M., Chibnall, J. T., Tait, R. C., Vander Wal, J. S., Baldwin, K. A., Antes, A. L., and Mumford, M. D. (2016). Professional Decision-making in Research (PDR): The validity of a new measure. Science and Engineering Ethics, 22(2): 391–416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-015-9667-8.

Fam, D., and O’Rourke, M. (Eds.). (2021). Transdisciplinary and Interdisciplinary Failures: Lessons Learned from Cautionary Tales. London: Routledge.

Hubbs, G., O’Rourke, M., and Orzach, S. H. (Eds.). (2020). The Toolbox Dialogue Initiative: The Power of Cross-Disciplinary Practice. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Leahey, E., Beckman, C. M., and Stanko, T. L. (2017). Prominent but less productive: The impact of interdisciplinarity on scientists’ research. Administrative Science Quarterly, 62(1): 105–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839216665364.

Lyall, C. (2019). Being an Interdisciplinary Academic: How Institutions Shape University Careers. London: Palgrave.

Lyall, C., Bruce, A., Tait, J., and Meagher, L. (2015). Interdisciplinary Research Journeys: Practical Strategies for Capturing Creativity. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

McIntosh, T., Antes, A. L., and DuBois, J. M. (2021). Navigating complex, ethical problems in professional life: A guide to teaching SMART strategies for decision-making. Journal of Academic Ethics, 19(2): 139–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-020-09369-y.

McIntosh, T., Antes, A. L., Schenk, E., Rolf, L., and DuBois, J. M. (2023). Addressing serious and continuing research noncompliance and integrity violations through action plans: Interviews with institutional officials. Accountability in Research, 1–33. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2023.2187292.

McIntosh, T., Sanders, C., and Antes, A. L. (2020). Leading the people and leading the work: Practical considerations for ethical research. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 6(3): 257–270. https://doi.org/10.1037/tps0000260.

National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, and Institute of Medicine. (2005). Facilitating interdisciplinary research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/11153.

Okhuysen, G. A., and Eisenhardt, K. A. (2022). Integrating knowledge in groups: How formal interventions enable flexibility. Organizational Science, 13(5): 370–383. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.13.4.370.2947.

Sabharwal, M., and Hu, Q. (2013). Participation in university-based research centers: Is it helping or hurting researchers? Research Policy, 42(6-7): 1301–1311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2013.03.005.

Shuffler, M. L., DiazGranados, D., and Salas, E. (2011). There’s a science for that: Team development interventions in organizations. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(2): 365–372. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721411422054.

Vienni-Baptista, B., Fletcher, I., and Lyall, C. (Eds.). (2023). Foundations of Interdisciplinary and Transdisciplinary Research: A Reader. Bristol, UK: Bristol University Press.

Weingart, P. (2000). Interdisciplinarity: The paradoxical discourse. In P. Weingart and N. Stehr (Eds.), Practicing Interdisciplinarity. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.