Airport Curbside and Terminal Area Roadway Operations: New Analysis and Strategies, Second Edition (2024)

Chapter: 2 Framework for Analysis of Airport Roadways and Curbsides

CHAPTER 2

Framework for Analysis of Airport Roadways and Curbsides

On-airport roadways are a unique class of roadways. Drivers who are unfamiliar with the airport mix with significant numbers of professionally driven large vans and buses. Entrances and exits at major airports operate at near-freeway speeds, while curbside roadways operate at much slower speeds, as drivers attempt to maneuver into and out of curbside spaces. Double- and triple-parking and jaywalking frequently occur on curbside roadways despite the visible presence of traffic enforcement officers.

The standard highway capacity analysis procedures can address some aspects of these conditions, but not the full spectrum of operating conditions that exist on airport terminal area and curbside roadways. The various users and types of airport roadways and curbsides and their unique operating characteristics are described in this chapter. Overviews are also presented of (1) the hierarchy of methods for analyzing airport roadway and curbside operations and (2) roadway capacity and quality-of-service concepts.

2.1 Users of Airport Roadways

Airport roadways provide access to and from the multiple land uses at an airport. These roadways serve vehicles transporting airline passengers and visitors (in this Guide, “visitors” refers to meeters/greeters and well-wishers accompanying or greeting airline passengers); employees of the airport, airlines, and other airport tenants; air cargo and mail; as well as vehicles used for the delivery of goods and services, maintenance, support of airport operations or construction, and other purposes.

A multitude of vehicle types now use airport roadways. They include private vehicles, rental cars, on-demand and pre-reserved taxicabs, transportation network company (TNC) vehicles, pre-arranged and on-demand limousines or town cars, door-to-door vans, courtesy vehicles, charter buses, scheduled buses, and service and delivery vehicles. Each vehicle/user type has its own special characteristics and affects airport roadway operations differently, as described below.

2.1.1 Private Vehicles

Privately owned and operated vehicles consist of automobiles, vans, pickup trucks, and motorcycles used to transport airline passengers; visitors; and employees of the airport operator, airlines, and other airport tenants. Motorists transporting airline passengers in private vehicles may use the curbside areas or other passenger drop-off and pickup areas, parking facilities (including cell phone waiting areas), or both.

2.1.2 Rental Cars

Rental car vehicles, including automobiles and vans, are used to transport airline passengers or visitors. These vehicles may be rented by a customer for the duration of their trip from either

rental car companies doing business on or near the airport (traditional rental car businesses) or peer-to-peer businesses that connect customers with individual car owners. Rental car customers may use the terminal curbside areas, rental car ready and return areas, or both. At most airports, the on-airport companies lease sites where customers can return and pick up their cars. Some airports require peer-to-peer companies to lease parking spaces where customers can interact with vehicle owners to return and pick up their cars.

2.1.3 On-Demand Taxicabs

On-demand taxicabs provide door-to-door service without prior reservations. This service is typically exclusive (i.e., for a single party) and provided in vehicles capable of transporting a driver plus four customers and their baggage in most developed nations (three-wheeled taxicabs and even motorcycles may be used to provide taxi service in developing nations). On-demand taxicabs are typically licensed and regulated by a municipal taxicab authority. Typically, on-demand taxicabs drop off passengers in the departures area and wait for deplaning passengers at a taxicab stand (or in a taxicab queue) at the curbside area next to the baggage claim area or other designated boarding area. At large airports, taxicabs may wait for customers in a remotely located taxicab holding or staging area until they are dispatched to the curbside taxicab stand or customer boarding area in response to customer demand.

2.1.4 Pre-reserved Taxicabs

Pre-reserved taxicab service is exclusive, door-to-door transportation provided in vehicles capable of transporting up to five customers plus their baggage. Rather than being provided on demand, as is traditional taxicab service, pre-reserved taxicabs are provided in response to pre-arrangements (i.e., prior reservations) made by airline passengers seeking to be picked up by a specific company or driver, including suburban taxicabs not regulated by the local municipal taxicab authority responsible for regulation of on-demand taxicab activity at the airport. Passengers with special needs, such as those with skis, golf clubs, large amounts of baggage, or physical disabilities, may request service by specific vehicles or companies. Typically, pre-reserved taxicabs or specially requested taxicabs are not allowed to wait at the curbside taxicab stand with on-demand taxicabs but instead wait for their customers at a separate curb space or alternative location.

2.1.5 Pre-arranged Limousines

Pre-arranged limousine service is exclusive door-to-door transportation provided in luxury vehicles capable of transporting a single party consisting of up to five customers (or more in stretch limousines) regulated by a local or state agency. Generally, limousine service is only available to customers who have made prior reservations (i.e., pre-arranged) and are greeted (or picked up) by a driver having a waybill or other evidence of the reservation. Some airport operators allow limousine drivers to park at the curbside and wait for customers; others require that the drivers park in a parking lot or other designated zone and accompany their customers from the terminal to the parking area.

2.1.6 On-Demand Limousines or Town Cars

Privately operated, on-demand, door-to-door transportation is also provided by exclusive luxury vehicles or “town cars” capable of transporting up to five passengers and their baggage. These services are similar to on-demand taxicab services but are provided in luxury vehicles with higher fares than those charged for taxicab services.

2.1.7 Transportation Network Company

A TNC offers door-to-door, non-stop transportation for a single party as well as other transportation options (e.g., point-to-point, shared-ride transportation in a vehicle transporting other

parties). Customers connect with and pay drivers, who are using personal vehicles, via the company’s smartphone application. Typically, TNCs drop off customers and meet waiting customers at the departures and arrivals curbsides, although at some airports alternate locations or a single curbside are used for both activities. Generally, TNCs are required to wait for customers in a remotely located hold or staging area until their affiliated company dispatches the driver to the customer boarding area to pick up a waiting customer. While some companies offer service in licensed limousines, these vehicles are classified and regulated as pre-arranged limousines rather than TNC vehicles.

2.1.8 Door-to-Door Vans

Door-to-door or shared-ride van services are typically provided in vans capable of transporting 8 to 10 passengers and their baggage. The service is available on both an on-demand and pre-arranged basis. Passengers, who may share the vehicle with other traveling parties, are provided door-to-door service between the airport and their homes/offices or other locations but may encounter several (typically four or fewer) en route stops. Typically, door-to-door vans wait for deplaning passengers at the curbside next to the baggage claim area. Similar to taxicabs, vans may be required to wait in hold or staging areas until they are dispatched to the curbside in response to customer demand.

2.1.9 Courtesy Vehicles

Door-to-door courtesy vehicle service is shared-ride transportation provided by the operators of hotels, motels, rental car companies, parking lot operators (both privately owned and airport-operated parking facilities), and others solely for their customers. Typically, no fare is charged because the cost of the transportation is considered part of (or incidental to) the primary service being provided. Courtesy vehicle service is provided in shuttle vehicles, including 8- to 12-passenger vans (e.g., those operated by small motels), minibuses, and full-size buses (e.g., those operated by rental car companies at large airports). Typically, courtesy vehicles pick up customers at designated curbside areas that have been reserved or allocated for their use.

2.1.10 Charter Buses and Vans

Charter bus and van service (also referred to as tour bus or cruise ship bus service) is door-to-door service provided to a party (or group of passengers) that has made prior reservations or arrangements for the service. Charter bus and van service is provided using over-the-road coaches, full-size buses, minibuses, and vans seating more than five passengers. As charter bus service is sporadically provided at most airports, curb space (or other passenger pickup areas) is either not allocated for charter buses or is shared with other transportation services. Exceptions include airports regularly serving large volumes of charter or cruise ship passengers. Typically, charter buses and vans unload passengers on the deplaning curbside. Charter buses and vans picking up passengers are required to wait in a remotely located hold area until the arrival or assembly of the party being provided the service. In some cases, such as charter buses carrying passengers to and from cruise ships, buses may be accompanied by small trucks carrying passenger luggage.

2.1.11 Scheduled Buses

Scheduled buses provide shared-ride service at established stops along a fixed route and operate on a fixed scheduled basis. Typically, scheduled buses are operated by a public agency and make multiple stops along a designated route, but in some communities, express or semi-express service is operated by a private operator or public agency. The location and amount of curb space allocated to scheduled buses depends on the volume of such service and the policy of the airport operator. Scheduled buses do not use hold lots or staging areas at most airports.

2.1.12 Active Transportation

Active transportation includes methods of travel such as walking, bicycling, kick scooters, and dockless electric scooters (or e-scooters). At airports in North America, these methods of travel have historically been rarely used by passengers for airport access or by the employees of the airport, airlines, or other tenants. However, their use may increase over time, particularly at locations where the communities surrounding the airport are well served by and promote active transportation modes. Normally, sidewalks or separate pathways are provided for pedestrians, while the operators of bicycles and scooters share roadway lanes with other vehicles.

2.1.13 Service and Delivery Vehicles

Service vehicles include a wide range of trucks, vans, semi-trailers, and other delivery vehicles used to transport goods, air cargo, mail, contractors, and refuse to and from the airport. Generally, deliveries are made at designated loading docks or warehouses, not at the terminal curbside. However, the pickup and drop-off locations for airline-operated small package delivery services, which are provided by small vans and light trucks, are at the terminal curbside at some airports.

2.1.14 Autonomous Vehicles

Autonomous cars and trucks are self-driving vehicles in which operation occurs without direct driver input into the control of steering, accelerating, and braking, and which are designed so that the driver is not expected to constantly monitor the roadway while the vehicle is operating in a self-driving mode. At present, AVs are not operating (or permitted to operate) on the airport curbsides or terminal area roadways of any North American airport. Limited tests have been conducted on AVs operating within parking lots and on secured airfields. As discussed in subsequent sections of this Guide, AVs are expected to operate on airport roadways in the future.

2.2 Types of Airport Roadways

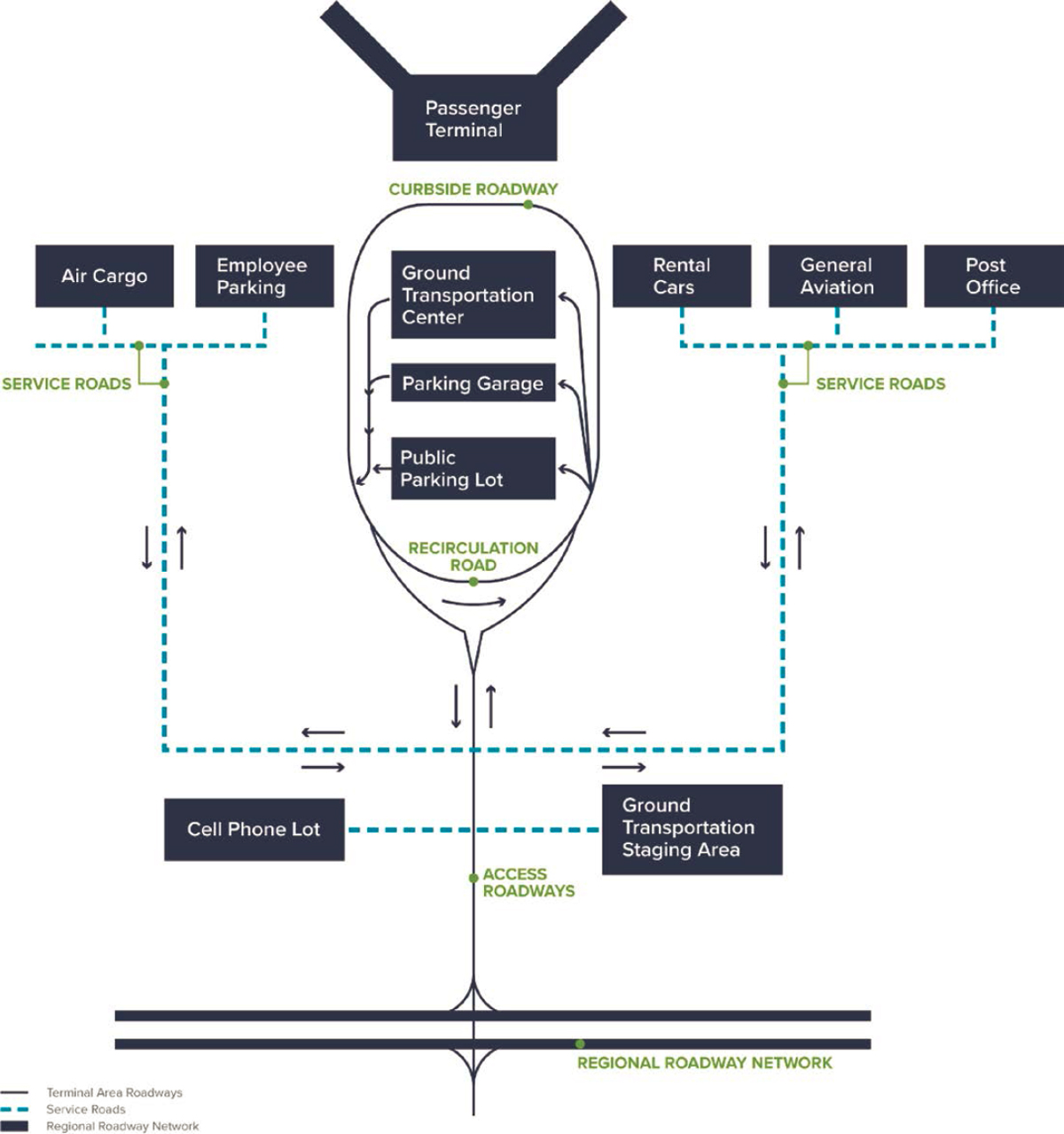

While the airport passenger terminal building and surrounding area (the terminal area) is the most prominent location at an airport, depending on the size, type, and distribution of airport land uses, less than half of all traffic at an airport may be associated with passengers and visitors proceeding to/from the terminal area; the remaining traffic is generated by non-airline-passenger activities, including employees and tenants. Regardless of airport size, the variety of land uses found at an airport requires a network of roadways to provide for inbound and outbound traffic and the internal circulation of traffic between land uses. The roadway network consists of the types of roadways depicted in Figure 2-1.

2.2.1 Access Roadways

For purposes of this Guide, airport access roadways are defined as the roadways linking the regional highway and roadway network with the airport terminal and other areas of the airport that attract large volumes of airline-passenger-generated traffic, such as parking and rental car facilities. Access roadways provide for the free flow of traffic between the regional network and the passenger terminal building or other major public facilities and typically have a limited number of decision points (i.e., entrances or exits). At large airports, access roadways are often limited-access roadways with both at-grade intersections and grade-separated interchanges. At smaller airports, access roadways often have at-grade intersections that may be signalized, controlled by stop signs, or have roundabouts (yield-sign controlled).

2.2.2 Curbside Roadways

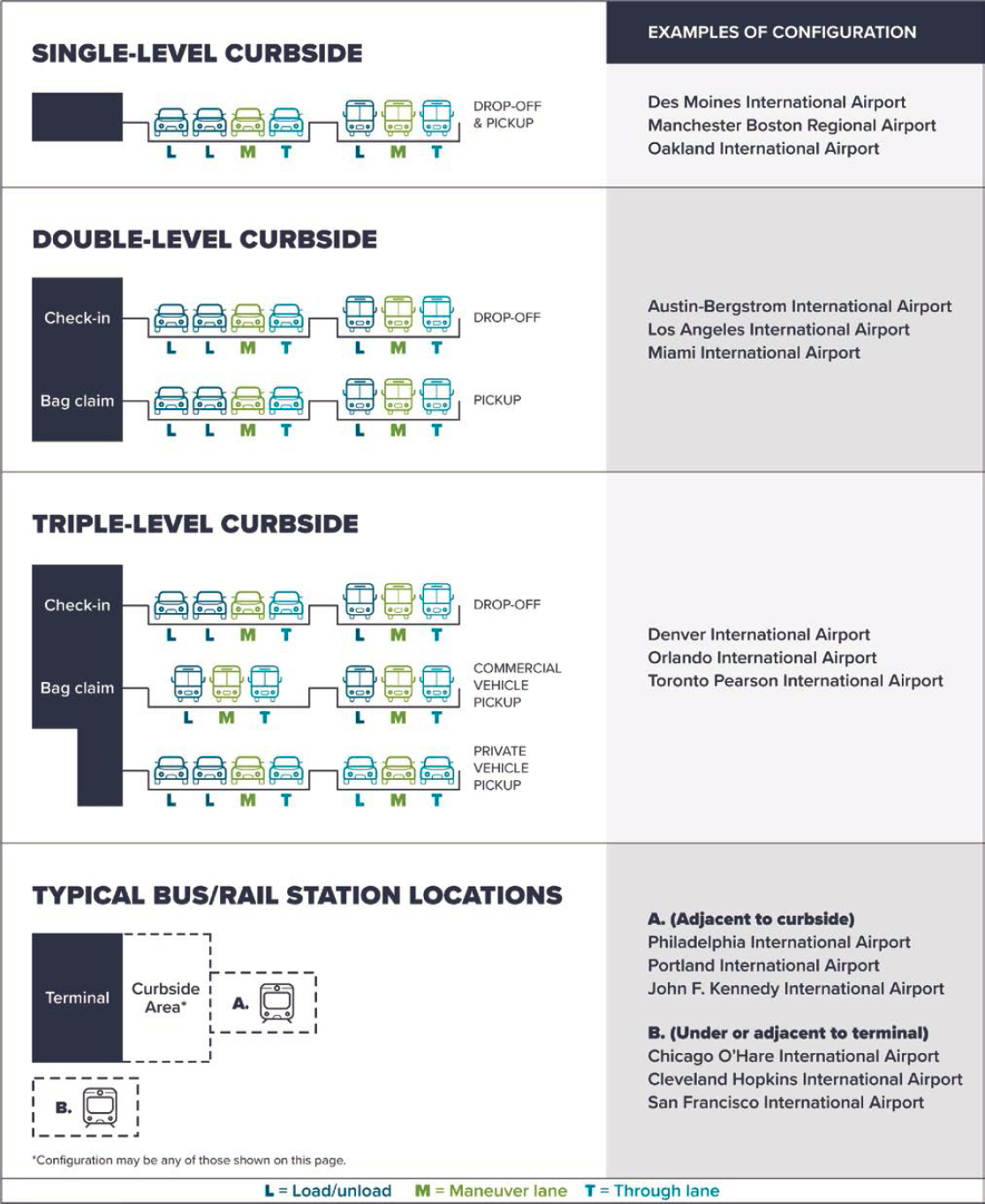

Curbside roadways are one-way roadways located immediately in front of the passenger terminal buildings where vehicles stop to pick up and drop off airline passengers and their baggage. Curbside roadways typically consist of (1) one or two inner lanes where vehicles stop or stand in a nose-to-tail manner while passengers board and alight, (2) an adjacent maneuvering lane, and (3) one or more through or bypass lanes. Curb space is often allocated or reserved along the inner lane for specific vehicles or classes of vehicles (e.g., taxicabs, TNCs, shuttle buses, courtesy vehicles, or curbside valet storage), particularly at the curbside areas serving baggage claim or passenger pickup.

As shown in Figure 2-2, depending on the configuration of the adjacent passenger terminal building, curbside roadways may include one, two, or more vertical levels and/or one, two, or more parallel roadways separated by raised medians (often called islands). At airports with dual-level curbsides, the upper-level curbside area is typically at the same level as airline passenger ticketing and check-in facilities inside the terminal building and is intended for passenger drop-off. The lower-level curbside area is typically at the same level as the baggage claim area and is intended for passenger pickup. At airports with multiple terminal buildings where one of the parallel roadways serves as a bypass roadway, cut-through roadways may be provided to allow vehicles to circulate between the inner and outer parallel roadways (and curbside roads).

2.2.3 Circulation Roadways

Circulation roadways generally serve a lower volume of traffic and may be more circuitous or less direct than terminal access roadways. Circulation roadways often provide a variety of paths for the movement of vehicles between the passenger terminal buildings, parking, cell phone waiting areas, and rental car facilities. Examples include return-to-terminal roadways that (1) allow motorists to proceed to parking after having dropped off airline passengers (or proceed from parking to the terminals) and (2) allow courtesy or other vehicles to return to the terminal (e.g., after having dropped off enplaning airline passengers and returning to pick up deplaning passengers on a different curbside roadway). Compared to access roadways, circulation roadways typically operate at lower speeds and allow for multiple decision points.

Access roadways, curbside roadways, and circulation roadways are considered “curbside and terminal area” roadways and are the focus of this Guide. Other airport roads include service and airfield roads, as described below.

2.2.4 Service Roads

Service roads link the airport access roadways with on-airport hotels, employee parking areas, employment centers (e.g., aircraft maintenance facilities or hangars), air cargo/air freight buildings and overnight parcel delivery services, loading docks/trash pickup areas, post offices, fixed-base operator (FBO)/general aviation areas, airport maintenance buildings and garages, military bases, and other non-secure portions of the airport that generate little airline passenger traffic.

The traffic generated by these land uses differs from that generated by the passenger terminal building in several respects. First, the traffic on service roads includes a higher proportion of trucks, semi-trailers, and other heavy vehicles than the traffic on curbside and terminal area roadways, which rarely serve trucks or delivery vehicles. Second, most drivers on the service roads (e.g., employees and drivers of cargo vehicles) use these roads frequently and are familiar with the roads and their destinations, unlike many drivers using the curbside and terminal area roadways.

For purposes of operational analyses, the service roads are similar to those found in an industrial park. Typically, they consist of two- to four-lane roads with generous provision for the turning paths of large trucks and semi-trailers and for entering and exiting vehicles, including separate or exclusive turning lanes.

2.2.5 Airfield Roads

A separate network of roads, located within the aircraft operating area or the airfield, is used by ground service equipment, including vehicles servicing aircraft, towing aircraft, or towing baggage carts and vehicles used for runway maintenance or emergency response. Often these vehicles are not licensed to operate on public streets. Only drivers who have received formal training from the airport are permitted to operate vehicles with an airport permit in secure or restricted areas. The design and operation of these roads are addressed in guidelines issued by the FAA Series 150 Advisory Circulars as well as ACRP Report 96: Apron Planning and Design Guidebook.

The remainder of this Guide addresses curbside and terminal area roadways only.

2.3 Operating Characteristics of Airport Terminal Area Roadways

The operating characteristics of airport terminal area roadways differ from those of other public roadways. This section describes the distinguishing operating characteristics of airport terminal area roadways, weaving sections, and curbside areas.

2.3.1 What Makes Airport Roadway Operations Unique

The main differences between the operating characteristics of airport terminal area access and circulation roadways and those of non-airport roadways include the following:

- A high proportion of motorists unfamiliar with airport roadways. Because most airline passengers fly infrequently (e.g., fewer than four times per year), they (and the drivers who drop them off/pick them up) are not familiar with the roadways at their local airport, much less the roadways at their destination airport(s). Unlike commuters, who rarely need to refer to roadway signs, airline passengers rely upon signs (or other visual cues) to guide them into and out of an airport and to/from their destinations at the airport. Picking up passengers may be particularly challenging for unfamiliar motorists, who must follow the appropriate signs, be aware of all the traffic and pedestrian activity at the curbside areas, and also identify their party among crowds of other passengers waiting to be picked up.

-

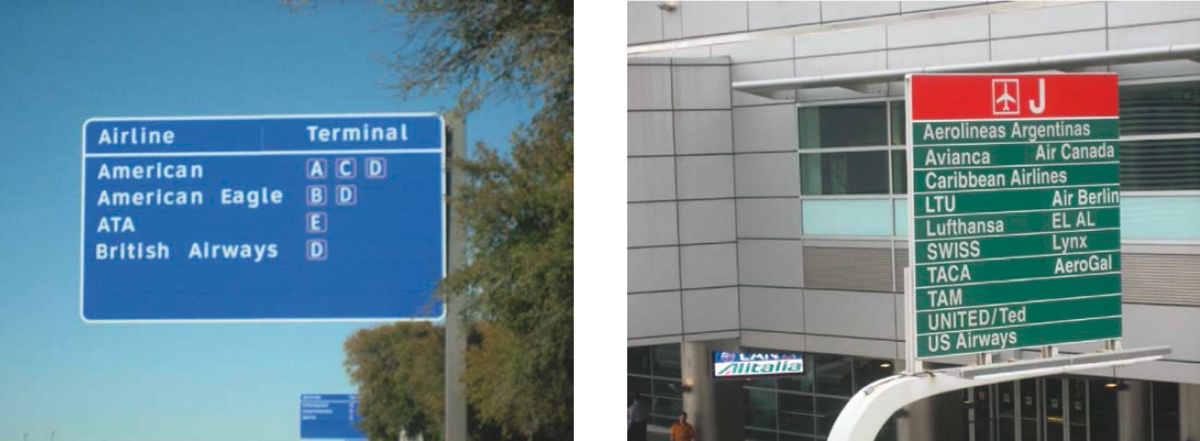

Complex wayfinding. Motorists entering an airport are provided with information concerning the locations of airlines (especially at airports with multiple terminals), parking products (e.g., hourly, daily, economy, and cell phone waiting area parking), rental car companies, and the entry to the departures/ticketing and arrivals/baggage claim levels (see Figure 2-3). Often the directional signs presenting this information to motorists (1) are closely spaced, limiting the time drivers have to comprehend and react to the messages, and (2) contain more information (i.e., more text) than those on comparable public roadways. For example, the general policy at U.S. airports is to display the name of every airline serving an airport, even those operating only a few times a week. Airport directional signs often include colors, fonts, symbols, and messages not commonly used on roadway signs governed by the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices for Streets and Highways (published by FHWA, U.S. DOT) or equivalent guidelines issued by other transportation agencies.

Because of the number, size, and complexity of signs at airports, motorists may not see regulatory or warning signs concerning height restrictions, speed limits, parking rates, security

-

regulations, use restrictions (e.g., authorized vehicles only), and other messages. Advertising and promotional signs visible to motorists (including column wraps) may be further distractions. These signs may result in an overload of information and cause motorists to decelerate in an attempt to read the signs.

-

Stressful conditions. Motorists operating on airport roadways are under more stress than typical motorists. This additional stress results from knowing that minor delays or wrong turns may cause a person to arrive too late to check baggage; claim a pre-reserved seat; greet an arriving passenger; or, in an extreme case, catch their flight. Congested airport roadways, closely spaced decision points, and complex signs can add to this stress and discomfort.

Factors adding to passenger stress at an airport include the need to connect from a car to a plane; from a car to a shuttle bus; find a parking place; find a passenger (Where is Aunt Meg?); find the correct place to drop off or pick up a passenger; locate a TNC, courtesy vehicle, or city bus stop; and so forth. Passengers realize the importance of making correct decisions so that they do not miss their flights or rides in an environment that is more complicated and anxiety-filled than a typical roadway situation. Each action at an airport is part of a chain of events, any one of which can go wrong and disrupt or delay a vacation, business meeting, or other important event.

-

A high proportion of heavy vehicles. More than 10 types of ground transportation service regularly operate on airport roadways, excluding maintenance vehicles, snowplows, or other vehicles used by airport operations. The characteristics of each service, the needs of the customers using the services, and the operating characteristics of the vehicles used to provide these services must be considered when developing physical and operational plans for airport curbside and terminal area roadways.

Courtesy vehicles, door-to-door vans, scheduled buses, and other large vehicles may represent 10% to 20% of the traffic volume on a terminal area roadway. On a typical public street, heavy vehicles (including single-unit and trailer trucks) may comprise less than 5% of the traffic volume. Capacity calculation procedures reduce the capacity of public highways with a high percentage of heavy vehicles reflecting the larger size and slower acceleration/deceleration rates of these vehicles.

However, the use of a capacity adjustment factor may not be necessary on airport terminal area roadways because courtesy vehicles, vans, and buses operating on those roadways do not interfere with the flow of other traffic to the extent that they do on public highways. On airport terminal area roadways, heavy vehicles (1) can operate at the range of prevailing speeds

-

typically found on airport roadways [i.e., 25 miles per hour (mph) to 45 mph] and (2) have sufficient power to accelerate and decelerate at rates that are comparable to those of private vehicles, as most airport roadways are level or have gentle grades, and are able to do so unless they are transporting standing passengers. In some locations, it is possible that large vehicles, such as courtesy vans or shuttle buses, may (1) obstruct motorists’ views of wayfinding and other signs and (2) interfere with traffic operations in the curbside through lanes as these courtesy vehicles maneuver into and out of curbside areas. In such cases, capacity adjustment factors may be warranted.

- A mix of experienced and inexperienced drivers. While most private vehicle drivers use an airport infrequently, 20% to 30% of the vehicles on airport roadways are operated by professional drivers who are thoroughly familiar with the on-airport roadways, as they use them frequently—perhaps several times each day. This difference contributes to vehicles operating at a range of speeds on the same roadway segment—slow-moving vehicles (e.g., drivers of private vehicles who are unfamiliar with the airport roadways attempting to read signs or complete required turns and maneuvers) and faster vehicles (e.g., taxicabs, TNCs, limousines, and courtesy vehicles operated by professional drivers familiar with the airport roadways who may ignore posted speed limits).

-

Recirculating traffic. Motorists, having dropped off a passenger, may recirculate along the airport’s roadways in order to enter a parking facility or return to the terminal. Motorists may be required by traffic control officers to exit the curbside area if they are not actively loading or unloading passengers, are unable to find an empty curbside space, or are waiting for an arriving passenger who is not yet at the curbside. Motorists exiting the curbside area may either wait in a cell phone or waiting area until their passenger arrives (which is encouraged by airport operators) or recirculate and return to the curbside. Table 2-1 indicates the percentage of private vehicle traffic found to be recirculating past the terminal, with some vehicles doing so multiple times.

These recirculating vehicles contribute to roadway congestion and represent unnecessary traffic volumes. Factors contributing to the volume and proportion of recirculating curbside roadway traffic include (1) an airport operator’s tolerance of vehicles lingering unnecessarily at the curbsides, (2) motorists not recognizing the difference between the published flight arrival time and the time when a passenger will actually arrive at the curbside, (3) motorists attempting to wait at the curbsides for passengers whose flights have been delayed, and (4) drivers of commercial vehicles who, in violation of airport regulations, are improperly soliciting customers along the curbside roadway. A lack of available close-in public parking spaces may cause motorists, seeking such spaces, to exit the terminal area and travel to remotely located parking areas.

- Atypical operations. The operation of airport roadways—particularly the primary entry and exit roads, terminal area roadways, and curbsides—differs from arterial roads in urban and rural areas. For example, airport roadways generally operate at slower speeds (35 mph or less), rarely have signalized intersections along the major entry and exit roads, primarily consist of one-way roadways, have fewer driveways or entry/exit points, and have no street parking.

Table 2-1. Percentage of private vehicles recirculating to the arrivals curbside.

| Airport | Recirculating (%) |

|---|---|

| Baltimore/Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport | 50% |

| San Francisco International Airport | 43% |

| Seattle-Tacoma International Airport | 30% |

| Dallas Love Field | 26% |

| Reagan Washington National Airport | 15% |

Source: Based on data provided by Ricondo & Associates, Inc., June 2009.

2.3.2 What Makes Airport Roadway Weaving Section Operations Unique

Weaving is defined as the crossing of two or more traffic streams traveling in the same direction along a length of highway without the aid of a traffic signal or other control device. A weaving maneuver occurs when vehicles enter a roadway segment from one side and exit the segment on the other while other vehicles do the opposite at the same time. The most common example of weaving occurs on freeways where an on-ramp is followed by an off-ramp a short distance later, and those two ramps are connected by an auxiliary lane. The weaving movement occurs when vehicles on the freeway move into the auxiliary lane to exit via the off-ramp, while vehicles from the on-ramp move from the auxiliary lane onto the freeway.

The operation of weaving and merging areas on airport roadways differs from the operation of these areas on non-airport roadways primarily because, on airport roadways, these operations occur at slower speeds than they do on freeways and arterial streets. Weaving analyses are generally conducted for freeways and arterial streets on which vehicles operate at higher speeds than on most airport roadways. At higher speeds, drivers require larger gaps between successive vehicles in order to merge into or weave across a traffic stream. The HCM provides a methodology for assessing weaving segments on freeways and multilane highways or collector-distributor roadways. These analyses are based on roadway free-flow speeds of 50 mph or higher. As such, the methodologies in the HCM for weaving sections are not suitable as is for airport roadways, which operate at lower free-flow speeds. Chapter 4 of this Guide presents alternative metrics and analysis methods for use on airport roadway weaving segments.

Upon entering an airport, motorists typically encounter a series of exits or turns leading to (1) non-terminal areas (e.g., economy parking, air cargo, general aviation), (2) close-in parking (e.g., hourly, daily, or cell phone waiting areas) and rental car return (by company), and (3) ticketing/departures and baggage claim/arrivals curbside areas. Upon exiting the airport, motorists may encounter a similar series of exits as well as roads leading back to the terminal and alternative regional destinations.

Often the distance between successive decision points is much less than that suggested by highway design standards established for limited-access highways because of the relatively short distances available between an airport entrance and the terminal area. Unlike a regional highway, where decision points may be separated by a mile or more, successive decision points on an airport roadway may be separated by 500 feet or less. Even though motorists on airport roadways are traveling at speeds that are slower than the speed of travel on freeways or arterial roadways (e.g., 35 mph or less), the limited distances between decision points, coupled with a driver’s unfamiliarity with the airport, may compromise the ability of a driver to recognize, read, and react to roadway directional signs, or cause the driver not to allow adequate time to complete required merging and weaving maneuvers.

2.3.3 What Makes Airport Curbside Operations Unique

As noted, curbside roadways consist of an inner curbside lane(s) where vehicles stop or stand typically in a nose-to-tail arrangement while passengers board and alight, an adjacent maneuvering lane that vehicles may occupy while decelerating or accelerating to enter or exit the curbside lane, and one or more “through” or bypass lanes. The operating characteristics of airport terminal curbsides differ significantly from those of most other roadways because of the interactions between vehicles maneuvering into and out of curbside spaces and vehicles traveling in the through or bypass lanes.

The capacity of a curbside roadway is defined both by the number of vehicles that can be accommodated while stopping to pick up or drop off passengers and the number of vehicles that

can be accommodated while traveling past the curbside in the through lanes. The capacity of the through lanes is restricted by vehicles that are double-parked (which is often tolerated on airport curbside roadways) or triple-parked as well as by pedestrian crosswalks. These capacity restrictions can cause traffic delays and the formation of queues that block vehicles trying to maneuver around stopped vehicles or attempting to enter and exit curbside spaces. (Additional information on the operating characteristics of curbside roadways is presented in Chapter 5.)

The length (or capacity) of a curbside area must be in balance with the capacity of the through lanes drivers use to enter and exit the curbside area. For example, a mile-long curbside served by only two lanes (one curbside lane and one through lane) would be imbalanced because, even though the curb length could accommodate a large number of vehicles, traffic flow in the single through lane would be delayed every time a vehicle maneuvered into and out of a curbside space or double-parked while waiting for an empty space. The reverse analogy or imbalance would occur with a very short curbside area and multiple through lanes.

Other operating characteristics of airport curbside roadways that differ from public roads, as further described in Chapter 5, include the following:

-

Dwell times. The length of time a vehicle remains stopped at the curbside area is referred to as “dwell time.” Generally, vehicles transporting a larger number of passengers and baggage require longer dwell times. The number of vehicles that can be accommodated along a given curbside length is determined by the size of the vehicles (i.e., the length of the stall each vehicle occupies, including maneuvering space in front of and behind the vehicle) and the amount of time each vehicle remains stopped at the curbside (i.e., the dwell time). Dwell times at a particular airport are affected by (1) enforcement policies (i.e., strict enforcement leads to shorter dwell times) and (2) local driver behavior (i.e., do drivers double-park in a way that allows other motorists to easily enter and exit the lane immediately adjacent to the terminal).

At most airports, private vehicles dropping off passengers typically have shorter dwell times than those vehicles picking up passengers (unless motorists are strictly prohibited from parking at the curbside while waiting for the passengers who have not yet arrived at the curbside). Thus, although airports generally have equivalent volumes of enplaning and deplaning airline passengers (and associated traffic volumes), the required capacity or length of an arrivals (pickup) curbside area is typically greater than that of the departures (drop-off) curbside area.

-

Maneuvering traffic and parking preferences. Unlike motorists on city streets, motorists parallel parking at airports rarely back into a curbside space. Motorists frequently stop with their vehicles askew to the travel lanes or sidewalk areas rather than maneuvering their vehicles into positions parallel to the curbside. By doing so, they may block or interfere with the flow of traffic in other lanes. Motorists leave space between successive vehicles to ensure that they are not blocked and to allow access to their trunk or baggage storage area.

Motorists using airport curbside roadways may stop in the second lane even if there is an empty space in the curbside lane to (1) avoid being blocked in by other motorists and (2) reduce the walking distances of passengers being dropped off (e.g., stop near a desired door or skycap position) or being picked up (e.g., stop at a point near where the person is standing or expected to exit the terminal building). Thus, motorists frequently stop in the second lane in front of the door serving the desired airline even though there may be an empty curbside space located downstream. The propensity to avoid inner lanes and double-park reflects local driver behavior or courtesy.

- Capacity of adjacent through lanes. Through-lane capacity is reduced by traffic entering and exiting curbside spaces, high proportions of vehicles double- and triple-parking, the use of the maneuver lanes, and other factors. As such, the capacity analysis procedures presented in the HCM are not applicable. Chapter 5 of this Guide presents suggested methods for calculating the capacities of curbside lanes and through lanes at airports.

-

Uneven distribution of demand. Curbside demand is not uniformly distributed during peak periods, reflecting (1) airline schedules and (2) the uneven distribution of the times passengers arrive at the enplaning curbside prior to their scheduled departures (lead time) or the times passengers arrive at the deplaning curbside after their flights have landed (lag times). Furthermore, stopped vehicles are not uniformly distributed along the length of a curbside area, reflecting motorist preferences for spaces near specific doors and skycap positions and their aversion to spaces near columns or without weather protection, if weather-protected spaces are available.

An aerial view of a busy terminal curbside area would show vehicles stopped adjacent to the door(s) serving major airlines. The airline with the largest market share generally will get its first choice of ticket counter and baggage claim area locations. Often, this airline selects the most prominent location, which generally is the area nearest the entrance to the curbside area. Thus, curbside demand is often heaviest at the entrance to the curbside area, causing double-parked vehicles and congestion in this area, while downstream areas remain unoccupied.

- Allocation of space for commercial vehicles and other uses. At most airports, curb space is allocated to commercial vehicles at the pickup curbside area. In the allocation of commercial vehicle curb space, multiple factors must be considered in addition to calculated space requirements, such as customer service, operational needs, airport policies, revenues, and perceived or actual competition among ground transportation services. Curb space may also be allocated for disabled parking, police vehicles, airport vehicles, valet parking drop-off/pickup, tow trucks, and other users.

- Allocation of private vehicle traffic to multiple curbside roadways. At airports having inner and outer curbside roadways, one curbside roadway is generally reserved for private vehicles and the other curbside roadway(s) is reserved for commercial ground transportation and other vehicles. It is beneficial to balance demand among all curbside roadways, but in practice, it is difficult to do so. This is because, if given a choice of terminal building curbside areas, private vehicle motorists—especially those unfamiliar with the airport—prefer to use the curbside area they perceive as being most convenient. Few motorists will respond to suggestions to use an alternate, less congested curbside area. For this reason, it is unusual to have multiple private vehicle drop-off (or pickup) curbside roadways. However, it is fairly common to direct commercial vehicles to multiple curbside areas.

-

Crosswalk location, frequency, and controls. Crosswalks provide for the safe movement of pedestrians between the terminal building and center-island curbside areas or a parking facility located opposite the terminal building. The use of crosswalks can be encouraged—and crossing between designated crossing locations discouraged—by providing numerous crosswalks at convenient (e.g., closely spaced) locations and/or fences or other barriers to pedestrians along the outer island.

However, providing multiple crosswalks has the potential to have an adverse effect on the flow of through traffic, thus increasing overall delay for arriving and departing motorists. Motorists are often required to stop at more than one crosswalk because traffic controls at the crosswalks (whether traffic officers or signals) may not be coordinated in such a way as to allow a continuous flow of through vehicles, such as what commonly occurs on an urban street. Multiple crosswalks also reduce the available length of curb space. A single crosswalk has less impact on through traffic and available curb length than multiple, unsignalized crosswalks, although multiple crosswalks are more convenient.

- Curbside lane widths. At most airports, curbside roadway lane widths are the same as those on public streets (e.g., 10 to 12 feet). Recognizing the tendency of drivers to double-park, some airport operators have elected to delineate one double-wide (e.g., 20 to 24 feet) curbside lane rather than two adjacent 10- to 12-foot lanes. (See Figure 2-4.)

- Availability of short-duration parking. Curbside demand can be influenced by the availability and price of conveniently located, short-duration (e.g., hourly) parking. If such parking is available, easily accessible, and reasonably priced, some motorists may choose to park and thus reduce

- the volume using the curbside areas. Similarly, the availability of cell phone waiting areas can help to reduce the volume of vehicles circulating past the pickup curbside areas and reduce average curbside dwell times. Conversely, the perceived lack of empty space, inconvenient access, and high costs for short-duration parking can discourage motorists from parking. A lack of empty spaces and high costs can increase curbside demands.

- Multi-terminal airports. Large airports may have multiple terminals, each with separate curbside areas, or with continuous curbsides that extend between terminal buildings. Curbside operations at each terminal may differ, reflecting the characteristics of the dominant passenger groups and airlines (e.g., international vs. domestic passengers or legacy vs. low-cost carriers).

- Recirculating or bypass traffic. At many airports, there is a significant proportion of non-stopping or bypass traffic on the terminal curbsides. This bypass traffic includes (1) recirculating traffic that, because of police enforcement or other reasons, passes the terminal curbside (particularly the deplaning curbside) more than once; (2) curbside traffic destined for a terminal or adjacent curbside section, which must bypass another curbside area on the way; and (3) non-curbside traffic traveling past the curbside (e.g., cut-through vehicles, employee vehicles, or airport service or maintenance vehicles). At some airports, large volumes of non-airport traffic use airport roadways to avoid congestion on parallel off-airport roads, thus contributing to peak-period roadway volumes and congestion.

-

Non-standard curbside configurations. While most airports have linear curbsides where vehicles stop bumper-to-bumper or nose-to-tail, a few airports have non-standard curbside configurations such as the following:

- Pull-through private vehicle spaces. As shown in Figure 2-5, the curbside areas at some overseas airports (as well as at some U.S. airports, e.g., St. Louis Lambert International and Little Rock National airports) have (or had) pull-through spaces arranged at 45-degree angles that allow motorists to pull through, similar to the way they would at a drive-through window.

- Angled commercial vehicle spaces. The commercial vehicle curbside areas at the airports serving Atlanta, Newark, and Orlando, among others, have angled spaces that require vehicles to back up to exit.

- Driver-side loading. As shown in Figure 2-6, at a few airports (e.g., Bush Intercontinental Airport/Houston and Mineta San Jose International Airport), the deplaning curbsides are located on the driver’s side of the vehicle, requiring private vehicle passengers to open the door and enter or exit the vehicle on the side away from the terminal building while standing in

-

- a traffic lane. Driver-side loading is used at some airports for taxicabs and TNCs because passengers may enter the cabin from either side of the vehicle.

- Brief parking zones—pay for curbside use. Some European airports do not provide free curb space but instead provide parking areas adjacent to the terminals that motorists can use for a fee. These areas can be configured parallel to the curbside (see Figure 2-7) or in a traditional parking lot adjacent to the terminal building (see Figure 2-8). In Europe, unattended vehicles are permitted in these zones, but in the United States, current security regulations prohibit unattended vehicles at the terminal curbsides.

- Supplemental curbsides. Some airports provide supplemental curbsides in or near parking structures or at remotely located sites. The airports serving Los Angeles and St. Louis have private vehicle curbside areas within parking structures (see Figure 2-9). The airports serving Boston, Las Vegas, San Francisco, and Seattle have commercial ground transportation vehicle curbside areas within parking structures.

The analytical procedures described in this Guide are most relevant for airports with traditional curb space configurations or layouts because of the differing dwell times and through-lane operations that occur with other configurations.

2.4 Overview of Analytical Framework Hierarchy

Subsequent chapters of this Guide present alternative methods for analyzing airport roadways, weaving sections, and curbside areas, recognizing the unique characteristics of these facilities. The alternative analysis methods or hierarchy differ in terms of (1) the level of effort or time needed to conduct the analysis, (2) the expected level of accuracy or reliability of the results, and (3) the necessary level of user skill or experience. The three methods—quick-estimation methods, macroscopic methods, and microsimulation methods—are described in the following paragraphs.

2.4.1 Quick-Estimation Methods

Quick-estimation methods, as the name suggests, can be used to produce preliminary analyses of roadway operations (or other facilities) simply and rapidly. They generally consist of look-up tables, simple formulas based on regression analysis of databases, or principles based on experience or practice, and are based on broad assumptions about the characteristics of the facility being analyzed. As such, they provide a first test of the ability of a roadway or other facility to properly accommodate the estimated requirements (existing or future) or the adequacy of a potential improvement measure.

Quick-estimation methods are ideal for quickly sizing a facility. The analyst can easily check which of many possible roadway design options is sufficient to serve the forecast demand. These methods, however, are less than satisfactory for estimating the operating performance of a given roadway or for refining a given design. If information on the actual performance of a given facility or how to refine a particular design is desired, then macroscopic methods should be used.

2.4.2 Macroscopic Methods

Macroscopic methods are used to consider the flows of vehicle streams, rather than the flows or operations of individual vehicles. The HCM and NCHRP Report 825: Planning and Preliminary Engineering Applications Guide to the Highway Capacity Manual, are examples of a set of macroscopic methods for evaluating roadway operations. As such, these methods approximate the interactions between individual vehicles, the behavior of individual drivers, and detailed characteristics of the roadways (or other facilities). Adjustment factors, typically developed through empirical observations or microsimulation methods, are often used to account for atypical vehicles or driver characteristics, traffic flow constraints, or other operational characteristics. These methods produce results that are considered acceptable and more accurate than quick-estimation methods and can be used with less effort and training than microsimulation methods.

Macroscopic methods can provide reliable estimates of the steady-state performance of a roadway averaged over a given analysis period. They are best for determining the refinements to a proposed design (or existing facility) that would eliminate capacity and congestion problems. These methods are less satisfactory for quantifying facility operations under heavy congestion conditions or on atypical roadway configurations.

Macroscopic methods are generally unsatisfactory for comparing alternative improvements that reduce but do not eliminate congestion. Under heavily congested conditions (hourly demand exceeding capacity), queuing vehicles from one part of the roadway affect both upstream and downstream operations in a manner that cannot be easily estimated using macroscopic methods. Macroscopic methods also cannot be used for unusual facility types or situations for which they were not designed. In those situations, microsimulation methods must be used.

2.4.3 Microsimulation Methods

Microsimulation methods consist of the use of sophisticated computer programs to simulate the operation of individual vehicles on simulated roadway networks. Each vehicle is assigned characteristics, such as a destination, performance capabilities, and driver behavior. Each roadway network is defined using characteristics such as number, length, and width of lanes; operating speeds; traffic controls; and pedestrian activity. As each simulated vehicle travels through the computerized roadway network, various aspects of its performance can be recorded based on its interaction with other vehicles and traffic controls. These performance statistics can be summarized in many ways, including commonly used performance measures, such as travel time and delays, travel speeds, and queue lengths. Also, some microsimulation models produce a visual display of the simulated roadway operations, which can be helpful when evaluating operations or presenting results.

Of the three methods for analyzing airport roadway conditions, microsimulation methods are the most complex and require the most effort and skill on the part of the user, but they also can produce the most detailed and reliable results. The use of microsimulation methods is suggested when macroscopic methods do not yield reasonable results, do not provide sufficient detail, or when the conditions being analyzed are outside the ranges addressed by macroscopic methods.

Additional information regarding the application of these three analysis methods is presented in subsequent chapters of this Guide.

2.5 Overview of Capacity and Quality-of-Service Concepts

The concepts of capacity and quality of service, as presented in the HCM, are fundamental to analyses of roadway and other transportation facilities and well understood by traffic engineers and transportation planning professionals. This section is intended to provide an overview of capacity and quality-of-service concepts for users not familiar with the HCM.

2.5.1 Capacity Concept

The capacity of a rectangle or a box can be easily defined by its size (i.e., its area or volume) as the maximum amount the object can accommodate is fixed. This is not true with objects that serve as “processors,” such as roadways, ticket counters, or runways. The capacity of a roadway, for example, depends not only on its size (e.g., the number of lanes and other geometric design aspects), but also on the characteristics of the vehicles using the roadway (e.g., their size, performance, spacing, speed, and many other operating characteristics). If all the vehicles on a roadway had identical sizes, distances apart, speeds, performance capabilities, driver skills, and other characteristics, then the capacity of the roadway (number of vehicles traversing a point or section during a unit of time) would be expected to be substantially higher than the capacity of the same roadway if it were serving a mix of vehicles with differing sizes, speeds, capabilities, and driver characteristics.

Accordingly, the capacity of a roadway—even roadways with the same number of lanes—varies based on the characteristics of the roadway (e.g., lane and shoulder widths, level or rolling terrain, intersection and driveway spacing, and traffic control types) and the characteristics of the vehicles and drivers using the roadway (e.g., the proportion of buses, single-unit or tractor-trailer trucks, daily and hourly variations in use, and familiarity of the typical drivers with the roadway). With knowledge of the characteristics of a roadway section and the vehicles (and drivers) using the roadway, it is possible to calculate its capacity—the maximum hourly rate of vehicles flowing past a point.

However, it is not possible or desirable for a roadway to operate at its capacity for sustained periods, as any minor disruption will cause congestion, which results in delays or lengthy queues and undesirable levels of safety and driver comfort. Also, demand rarely is sustained at a constant level over an hour; it frequently varies within the hour. Thus, roadway capacity, while stated in

terms of “base” vehicles (e.g., passenger-car equivalents) per hour, is sometimes computed for only the peak 15-minute flow rate within that hour. In addition, roadway operations are characterized in terms of quality-of-service measures and service flow rate—the maximum flow rate that can be accommodated while maintaining a desired quality of service.

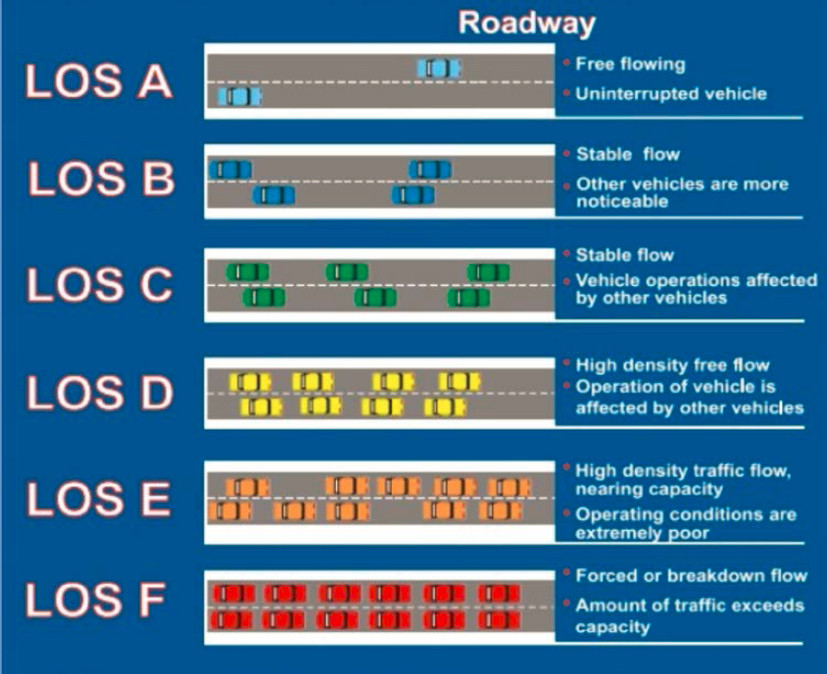

2.5.2 Quality-of-Service Concept

Quality of service is a qualitative measure of how travelers perceive the performance of freeways, urban streets, and signalized and unsignalized intersections. Quality of service is often stratified quantitatively into levels of service indicated using the acronym LOS (e.g., the A-to-F LOS scale common within the HCM, as shown in Figure 2-10). However, the concept is broader than levels of service and can include system-oriented metrics such as the sufficiency of the roadway to provide adequate capacity. Further detail on levels of service can be found in Chapter 5, “Quality and Level-of-Service Concepts,” in the HCM.

Performance measures from the perspective of the system provider are also useful in characterizing the performance of roadways. One of these measures, sufficiency, is particularly well suited to airport terminal roadways where the complexities of the travel environment preclude accurate prediction of service measures such as delay. Quality of service is defined in terms of parameters that can be perceived by the users of a transportation facility and that can be measured and predicted. Common performance measures used to characterize quality of service include (1) the density of the traffic flow (passenger cars per mile per travel lane) for a freeway or other unsignalized multilane roadway and (2) control delay (seconds per vehicle) for signalized and unsignalized intersections. Sufficiency is often characterized by capacity-related performance measures such as the volume-to-capacity or demand-to-capacity ratio.

Source: Maryland Department of Transportation

2.5.3 Acceptable Performance for Airport Roadways

As noted, performance measures are typically used to determine if a roadway can properly accommodate existing or future traffic operations or to compare alternative improvement options. As noted previously, the metric of “sufficiency” is recommended for airport roadways. On airport roadways, a sufficiency of “under capacity” is typically considered to be the minimum “acceptable” level of performance because of the lack of alternative travel paths, the significant negative consequences resulting from travel delays (e.g., passengers missing their flights), and the ability to accommodate higher volumes during short periods and unusually busy days (such as during holidays) without reaching failure. In comparison, on regional freeways and arterials and in densely developed urban areas, a sufficiency of “near capacity” is often considered “acceptable” because motorists traveling on regional roadway networks can select alternative travel paths should their preferred path be congested. These metrics are discussed further in the following paragraphs and in detail in Chapter 5.

2.5.4 Commonly Used Definitions for Planning Applications

NCHRP Report 825: Planning and Preliminary Engineering Applications Guide to the Highway Capacity Manual provides a guide to the assessment of intersection capacity and the use of sufficiency as a performance measure. It is proposed that similar performance measures be used for the assessment and planning of airport curbsides and terminal area roadways. The sufficiency categories proposed for airport curbsides and terminal area roadways are as follows:

- Under capacity—Operating beneath the capacity of a roadway or curbside. All vehicular traffic demands can be accommodated, delays are low to moderate, and maneuverability is acceptable. For comparison with the level-of-service grades used in the HCM, this is the equivalent of LOS A through LOS C. As previously noted, it is proposed that airport curbsides and roadways be planned and designed for a sufficiency of under capacity.

- Near capacity—Operating near the capacity of a roadway or curbside. Demand is approaching the roadway capacity, delays are moderate to high, and maneuverability is somewhat restricted. For comparison with the level-of-service grades used in the HCM, this is the equivalent of LOS D. As previously described, when analyzing existing operations or designing new facilities, especially at large-hub airports, airport management may elect to accept near capacity depending on customer expectations, incremental costs, expected remaining useful life, and other factors, realizing that the service level experienced may decrease to at capacity or over capacity on some peak days of the year.

- At capacity—Operating at or very close to the capacity of a roadway or curbside. Demand is near or at the roadway capacity, delays are high, and maneuverability is highly restricted. For comparison with the level-of-service grades used in the HCM, this is the equivalent of LOS E.

- Over capacity—Operating over the capacity of a roadway or curbside. Demand for roadways cannot be accommodated, delays are high and growing, maneuverability is highly restricted, and queues extend back from the terminal area. For comparison with the level-of-service grades used in the HCM, this is the equivalent of LOS F. Regularly occurring operations that are over capacity are not acceptable to airport users.

The International Air Transport Association (IATA) defines four comparable sufficiency categories (or level-of-service classifications) for analysis of passenger terminal facilities: over-design, optimum, sub-optimum, and under-provided. IATA recommends that airport planners strive to reach the optimum range for each passenger terminal facility to strike a reasonable balance between service quality and costs.