Methods of Airport Arts Program Management (2024)

Chapter: 3 Key Findings

CHAPTER 3

Key Findings

The aim of this synthesis is to outline the management methods employed by airport arts programs and their administrators for program operation and management. To accomplish this goal, the synthesis team utilized a sequential explanatory mixed-methods design with a wide-scale survey followed by a set of focus groups. Findings are summarized for both the survey data and focus groups by thematic concepts. The survey captured a total of 61 respondents, and 14 airports participated in a set of focus groups.

3.1 List and Map of Participating Airport Arts Programs

A list of all 506 commercial airports across the United States and territories was obtained using the CY22 Enplanements at All Commercial Services Airports dataset (FAA, 2023b). The data was filtered to identify only primary airports, yielding 383 airports consisting of large hubs (n = 30, 7.8%), medium hubs (n = 35, 9.1%), small hubs (n = 80, 20.9%), and non-hubs (n = 238, 62.1%). As a result, all airports included had at least 10,000 commercial enplanements in 2022.

All 383 airports were contacted by email or phone with online general inquiry forms, resulting in 189 airports (49.3%) agreeing to participate. After an email was sent to these 189 airports, 46 airports (24.3%) indicated they did not have an arts program and did not take the survey, yielding 143 eligible airports that agreed to take the survey. At the conclusion of the survey, 61 responses were received, representing 55 airports (38.5%).

Of the 55 airports that responded, eight were large hubs (14.5%), 13 were medium hubs (23.6%), 14 were small hubs (25.5%), and 20 were non-hubs (36.4%). Given that many non-hubs do not have arts programs, and that no precise count of airports with arts programs currently exists, representativeness cannot be determined across all hubs. However, the survey did provide a good cross section of hub typologies with proportionately more non-hubs (see Table 4).

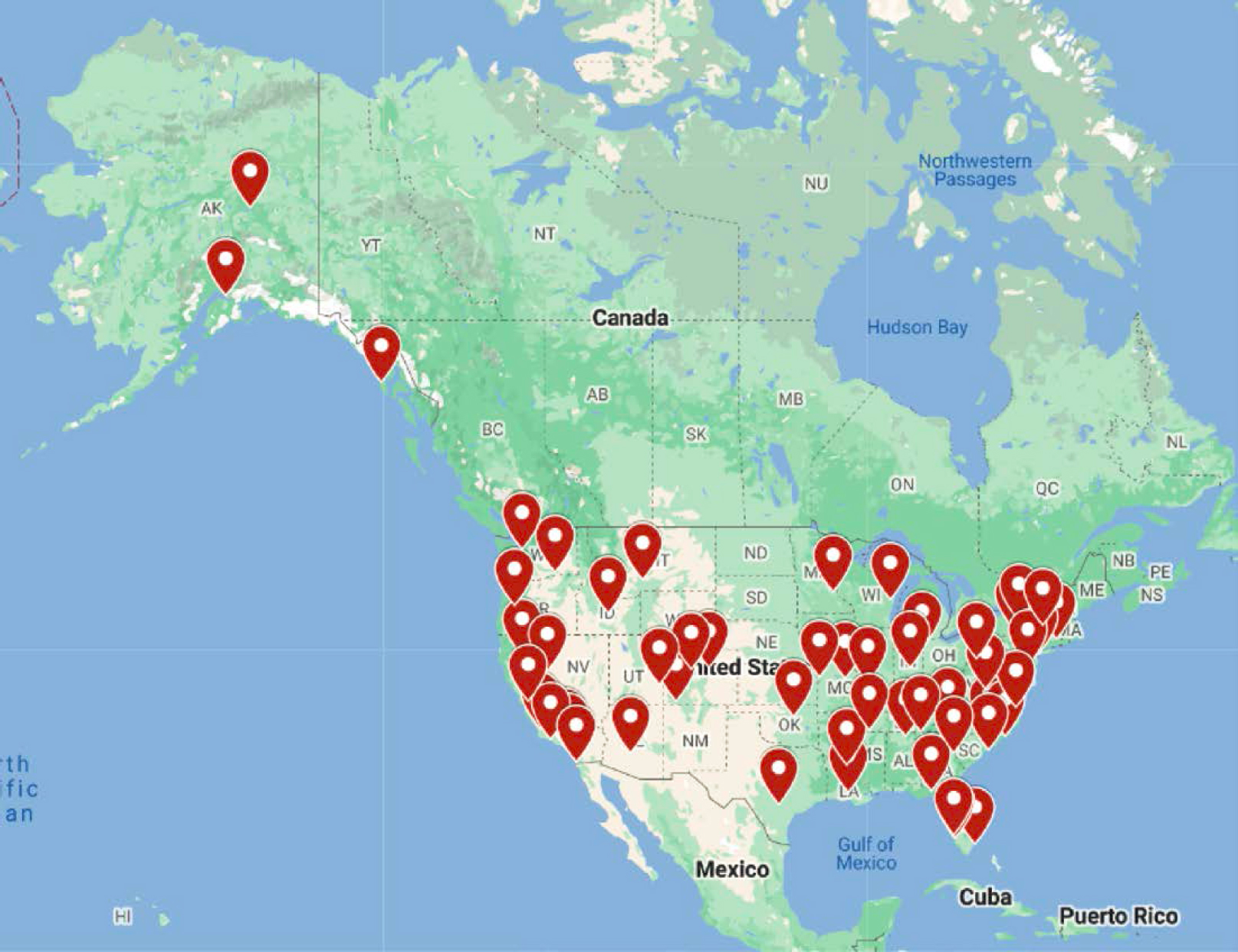

Geographically, the 55 survey responses spanned the continental United States and Alaska (see Figure 5). There is a small gap in some of the northwestern Midwest states. However, some of these states (e.g., Nebraska and Wyoming) did respond to the survey inquiry but noted that they did not have an arts program.

The scope and scale of the airport arts program respondents varied widely as well. See Table 5 for the age of arts programs among survey respondents.

At the conclusion of the survey, respondents were asked to participate in a focus group panel to explore the management practices of their arts program. A total of 14 airports agreed to participate in a focus group (see Table 6).

Table 4. Survey respondents by hub status and CY 2022 enplanements.

| IATA* | Airport | State | Hub Size | CY 2022 Enplanements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGS | Augusta Regional Airport (Bush Field) | Georgia | Non-hub | 269,937 |

| ALB | Albany International Airport | New York | Small hub | 1,277,329 |

| ANC | Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport | Alaska | Medium hub | 2,604,308 |

| AVL | Asheville Regional Airport | North Carolina | Small hub | 919,929 |

| BDL | Bradley International Airport | Connecticut | Medium hub | 2,844,713 |

| BFI | King County International Airport (Boeing Field) | Washington | Non-hub | 21,717 |

| BZN | Bozeman Yellowstone International Airport (formerly Gallatin Field) | Montana | Small hub | 1,136,170 |

| CHA | Lovell Field | Tennessee | Small hub | 431,984 |

| CNY | Canyonlands Regional Airport | Utah | Non-hub | 18,841 |

| COU | Columbia Regional Airport | Missouri | Non-hub | 81,643 |

| DEN | Denver International Airport | Colorado | Large hub | 33,773,832 |

| DRO | Durango–La Plata County Airport | Colorado | Non-hub | 183,273 |

| EAU | Chippewa Valley Regional Airport | Wisconsin | Non-hub | 17,346 |

| EGE | Eagle County Regional Airport | Colorado | Non-hub | 214,998 |

| EUG | Mahlon Sweet Field | Oregon | Small hub | 781,745 |

| EWR | Newark Liberty International Airport | New Jersey | Large hub | 21,774,690 |

| FAI | Fairbanks International Airport | Alaska | Small hub | 513,160 |

| FAY | Fayetteville Regional Airport (Grannis Field) | North Carolina | Non-hub | 165,721 |

| FLL | Fort Lauderdale–Hollywood International Airport | Florida | Large hub | 15,370,165 |

| FWA | Fort Wayne International Airport | Indiana | Small hub | 359,800 |

| GRB | Green Bay Austin Straubel International Airport | Wisconsin | Non-hub | 301,377 |

| HSV | Huntsville International Airport (Carl T. Jones Field) | Alabama | Small hub | 587,572 |

| IND | Indianapolis International Airport | Indiana | Medium hub | 4,209,416 |

| ITH | Ithaca Tompkins International Airport | New York | Non-hub | 56,509 |

| LAX | Los Angeles International Airport | California | Large hub | 32,326,616 |

| LFT | Lafayette Regional Airport (Paul Fournet Field) | Louisiana | Non-hub | 226,249 |

| LGB | Long Beach Airport (Daugherty Field) | California | Small hub | 1,600,987 |

| MCI | Kansas City International Airport | Missouri | Medium hub | 4,796,476 |

| MEM | Memphis International Airport | Tennessee | Medium hub | 2,163,692 |

| MLU | Monroe Regional Airport | Louisiana | Non-hub | 89,347 |

| MSP | Minneapolis–St. Paul International Airport (Wold–Chamberlain Field) | Minnesota | Large hub | 15,242,089 |

| MYR | Myrtle Beach International Airport | South Carolina | Small hub | 1,706,591 |

| OAJ | Albert J. Ellis Airport | North Carolina | Non-hub | 138,235 |

| ORF | Norfolk International Airport | Virginia | Medium hub | 2,065,116 |

| PGD | Punta Gorda Airport | Florida | Small hub | 920,673 |

| PHL | Philadelphia International Airport | Pennsylvania | Large hub | 12,421,168 |

| PHX | Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport | Arizona | Large hub | 21,852,586 |

| PIT | Pittsburgh International Airport | Pennsylvania | Medium hub | 3,918,968 |

| PSC | Tri-Cities Airport | Washington | Small hub | 390,762 |

| RDD | Redding Municipal Airport | California | Non-hub | 98,725 |

| RNO | Reno–Tahoe International Airport | Nevada | Medium hub | 2,132,856 |

| RSW | Southwest Florida International Airport | Florida | Medium hub | 5,132,694 |

| SAN | San Diego International Airport (Lindbergh Field) | California | Large hub | 11,162,224 |

| SAT | San Antonio International Airport | Texas | Medium hub | 4,751,610 |

| SBA | Santa Barbara Municipal Airport (Santa Barbara Airport) | California | Small hub | 610,916 |

| SBP | San Luis Obispo County Regional Airport (McChesney Field) | California | Non-hub | 273,690 |

| SHD | Shenandoah Valley Regional Airport | Virginia | Non-hub | 10,400 |

| SIT | Sitka Rocky Gutierrez Airport | Alaska | Non-hub | 94,648 |

| SJC | San Jose Mineta International Airport | California | Medium hub | 5,590,137 |

| SNA | John Wayne Airport | California | Medium hub | 5,536,313 |

| STL | St. Louis Lambert International Airport | Missouri | Medium hub | 6,709,080 |

| SUN | Friedman Memorial Airport | Idaho | Non-hub | 100,586 |

| SWO | Stillwater Regional Airport | Oklahoma | Non-hub | 28,867 |

| SYR | Syracuse Hancock International Airport | New York | Small hub | 1,244,921 |

| TLH | Tallahassee International Airport | Florida | Non-hub | 397,029 |

*IATA: International Air Transport Association.

Table 5. Age of arts programs among survey respondents.

| Age of Arts Program | Number of Programs |

|---|---|

| Planning phase | 3 |

| Less than a year | 6 |

| 1 to 2 years | 3 |

| 3 to 5 years | 12 |

| 6 to 10 years | 5 |

| More than 10 years | 25 |

| No response | 1 |

Table 6. Focus group participants by hub status and CY 2022 enplanements.

| IATA* | Age of Arts Program | State | Hub Size | CY 2022 Enplanements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALB | More than 10 years | New York | Small hub | 1,277,329 |

| BDL | 1 to 2 years | Connecticut | Medium hub | 2,844,713 |

| DEN | More than 10 years | Colorado | Large hub | 33,773,832 |

| EGE | Less than 1 year | Colorado | Non-hub | 214,998 |

| IND | More than 10 years | Indiana | Medium hub | 4,209,416 |

| LAX | More than 10 years | California | Large hub | 32,326,616 |

| LGB | 3 to 5 years | California | Small hub | 1,600,987 |

| MCI | 1 to 2 years | Missouri | Medium hub | 4,796,476 |

| OAJ | More than 10 years | North Carolina | Non-hub | 138,235 |

| PHX | More than 10 years | Arizona | Large hub | 21,852,586 |

| PIT | More than 10 years | Pennsylvania | Medium hub | 3,918,968 |

| RNO | More than 10 years | Nevada | Medium hub | 2,132,856 |

| SBA | More than 10 years | California | Small hub | 610,916 |

| SNA | More than 10 years | California | Medium hub | 5,536,313 |

*IATA: International Air Transport Association.

3.2 Governing Structures, Management Design, and Types of Leadership and Stakeholders of Airport Arts Programs

Management structures across different airports vary due to a combination of factors, including the size and complexity of the airport, governance type, regulatory environment, availability of financial resources, geographical and cultural influences, and strategic priorities. Large airports with extensive facilities and operations may require more complex management structures compared to smaller airports. Additionally, these differences influence decision-making processes and management approaches. The diversity of management approaches is also influenced by the financial resources available, along with regional differences and cultural norms. Finally, each airport’s strategic goals and priorities influence the design of its management structure to align with specific goals.

Among the 61 respondents, 33 (54%) noted that they were directly involved in the day-to-day operations of the arts program, while 17 (28%) noted that they were directly involved, but it was not their primary responsibility. The remaining 11 (18%) responses were from individuals who either oversaw the arts program from a governance standpoint (n = 7) or were responsible for the care and maintenance of the artworks in the program.

Of the 33 respondents who stated they were directly involved in the day-to-day operations of the arts program, 17 (51.5%) had a job title that reflected this work: Airport Arts Director, Manager, Curator, or similarly titled role. Position titles were often administrative (n = 13; 39.4%), with more than half of those positions associated with marketing, communications, public relations, or a similar department, and with the remaining positions falling under operations (i.e., landside and terminal).

At some long-standing and well-established arts programs, the titles and roles function as standalone departments, such as the Art Program Director at LAX or the Airport Museum Director at Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport (PHX). During the focus groups, several respondents noted that their roles are connected to marketing or similar administrative departments. For example, at Santa Barbara Municipal Airport (SBA), the position title is Marketing Supervisor, and the marketing department oversees and manages the airport arts program; meanwhile, at IND, the position title is Arts Program and Marketing, and the job sits within the public affairs department. At small or medium hubs, the placement of the arts program within the marketing department allows for streamlined communication, enhanced coordination, and an alignment of goals and resources. A respondent from Kansas City International Airport (MCI) noted that, “being connected with marketing really helps in terms of how we view the art collection; it’s not an operational asset, it’s a marketing asset.” A respondent at SBA also noted that they have used their advertising to bring in art and used art creatively with their advertising partners, noting that the tie between the two allows for nontraditional advertising within the airport space.

3.2.1 Development and Maintenance of Advisory and Selection Committees

Governance structures vary from airport to airport, and arts programs are no exception. The three most common governance structures among the 55 airport survey respondents were an established Arts Manager, Arts Director, or Arts Executive Director (n = 17; 30.9%); art selection committees (n = 17; 30.9%); and art advisory committees (n = 12; 21.8%).

An Airport Arts Manager, Arts Director, or Arts Executive Director is a managerial position at the airport and oversees the development, implementation, and management of an airport’s arts program. They are responsible for curating and maintaining the airport art collection; coordinating with artists, art organizations, and stakeholders; and ensuring that art installations align with the airport’s aesthetic, cultural, and operational goals. Additionally, they may manage budgets, procure artworks, oversee installations, and coordinate public engagement initiatives such as exhibitions, tours, and educational programs. Among the 14 focus group participants, ALB, Denver International Airport (DEN), LAX, PHX, PIT, and Reno–Tahoe International Airport (RNO) (n = 6; 42.9%) have an Arts Manager, Arts Director, or Arts Executive Director. With the exception of RNO, these positions are held by either city or county employees.

Art selection committees are tasked with the responsibility of choosing artworks. A committee may consist of artists, curators, art historians, administrators, community representatives, and other stakeholders with relevant expertise or interests. The selection committee reviews proposals from artists or art organizations; considers factors such as artistic quality, suitability for the airport environment, cultural relevance, and budget constraints; and then makes recommendations for acquisition or commissioning of artworks (see Photo 5). Pittsburgh International Airport (PIT) has a small selection panel composed of staff from different departments in the airport, including construction and architects, as well as stakeholders and partners. Likewise, Long Beach Airport (LGB) uses a committee of airport employees who volunteer their time to review and select pieces. ALB uses an external committee composed of regional professionals appointed by the arts program manager, who also vote on larger projects.

A few airports had similar stories about the genesis of their selection committees. DEN is connected to the city mayor’s office, and as part of city policy, which eventually became airport art policy, they are required to have a selection panel. DEN creates a unique selection committee for each project. The committee typically consists of one artist, one arts and cultural professional, one city council member, three community members, and one voting member from the airport

who cannot be the arts manager. At DEN, the arts manager cannot vote and does not select the artwork. Other airports noted a similar origin of their selection committees, as either a requirement from city or county government or as part of existing public arts policies that were adopted by the airport authority. In summary, the established policy is the genesis for the airport policy for selection committees.

The selection committee at RNO has a different origin. Although they are not mandated by a city or county government to create an advisory committee, the RNO advisory committee, which advises and selects artwork, instead resulted from an internal board decision.

A result of this type of top-down selection is that many departments at the airport had little knowledge of the artworks selected. Therefore, an internal committee was formed that collaborates with the larger selection committee to ensure that all departments impacted by the inclusion of a new art piece will have some knowledge and be able to work with the artist before the piece is installed.

The inclusion of greater diversity among airport employees was a common theme in the focus group discussions. IND respondents discussed how their selection committee is transforming. The arts director sits on the committee along with one person from the arts council, a senior director. In addition, three to four artists hold rotational positions on the committee. In the past few years, they have made a concerted effort to include staff from the airport. In particular, IND noted that, as they grow the airport presence on the committee, they would like to see a custodian or maintenance member join: “somebody who is going to be walking actually past the art every day.” They also see inclusion as bringing more perspectives to the selection committee, because frontline employees are often not invited to participate on selection committees.

For some small-hub and non-hub airports, selection committees either have been difficult to manage or support or have not been launched. Some young arts programs (less than three years old) remarked on the benefits of selection committees, but have not yet established them.

Across the focus group conversations, the idea of a selection committee was a common theme and seen as a positive aspect of the process. Respondents expressed that a selection committee provides diverse perspectives, expertise, and assessment when choosing the most suitable pieces and also fosters transparency, fairness, and confidence in the selection process.

Airport arts advisory committees are slightly different from airport art selection committees in that they take a more comprehensive approach and provide ongoing guidelines and oversight for the airport’s arts program. Advisory committees are typically composed of artists, art professionals, community representatives, and airport stakeholders who are tasked with ensuring that

airport art reflects the local culture, enhances the passenger experience, and meets aesthetic and quality standards. The committee may review proposals from artists and arts organizations, make recommendations for acquisitions or commissions, and collaborate with architects and designers to integrate artwork into airport facilities. Additionally, the committee may develop policies as well as provide guidelines for public arts policies, community engagement initiatives, and long-term planning for the airport’s arts program. Advisory committees often serve as sounding boards that offer diverse viewpoints and ensure that decisions align with airport needs. Among surveyed respondents, 12 (21.8%) noted that they use advisory committees. While not all programs that use a selection committee also have an advisory committee, 9 (16.4%) programs with an advisory committee also had a selection committee—which is notable, because some airport’s advisory committees also function as selection committees.

Many airport arts programs have advisory committees because they were commissioned by the city or county government as part of their existing policies. However, in some cases, this situation has also created challenges (e.g., cumbersome approval processes, changing committee members) in the arts advisory committees. Consequently, some airports have had to create workarounds or internal committees to support processes.

Those airports that have an advisory committee often consist of external participants. For example, ALB holds an advisory committee with members from a variety of backgrounds, including architects, philanthropists, and art professionals. ALB helps determine the structure, scope, and functions of the program, but does not hold any official decision-making power. Alternatively, some programs see the benefit of airport personnel on their advisory committees. During their arts program’s development, PIT has established a small advisory panel comprised of airport personnel and residents from the region who advise how artworks will impact the airport from installation to ongoing maintenance. They, too, may not have decision-making authority, but they guide how the airport arts program develops.

Throughout the focus groups, discussions about advisory committees and selection committees sometimes overlapped. While selection committees were widely praised, advisory committees could sometimes encounter challenges, such as delays or structures that stifle creativity and innovation, logistical challenges regarding meetings and full participation, and management of conflicting opinions about airport aesthetics and policies. Despite these challenges, several airports reported that the advisory committee as a governing body is a good idea because it ensures expertise and community engagement in shaping the airport arts program.

Among some of the other governing structures utilized by airport arts programs, 11 (20%) survey respondents had an arts board of directors or governance board. Similar to an advisory committee, a board of directors provides governance, strategic guidelines, and oversight to an arts program. Seven (12.7%) of the 55 survey respondents had both an advisory committee and a board of directors: King County International Airport (BFI), Fort Lauderdale–Hollywood International Airport (FLL), MCI, Minneapolis–St. Paul International Airport (MSP), PIT, Tri-Cities Airport (PSC), and SAN. During the focus groups, remarks about boards of directors came up only when discussing the airport in general, but not in connection to the arts program specifically.

3.2.2 Creation and Fostering of Stakeholder Interest

Stakeholders are individuals, groups, or entities with a vested interest in an arts program. Stakeholders typically have varying levels of influence and may have different priorities, perspectives, and expectations. Effective stakeholder management involves identifying and understanding their interests, engaging with them proactively, and considering their input in decision-making processes to ensure alignment, build trust, and achieve mutually beneficial outcomes.

In the survey, stakeholder groups were identified in three main categories: stakeholder committee or group, artist committee or group, and volunteer committee or group. Among the 51 respondents to this question, 10 (19.6%) indicated that they have an artist committee or group. Six airports did not indicate that they had an artist committee but did indicate that they worked with artists through arts councils and city or county public arts committees. Both DEN and PIT identified working with artists on various committees and noted that the process of working with artists usually is a result of other advisory and selection committees.

In the survey (n = 55), seven (12.7%) airports indicated they have a stakeholder committee at their airport: BFI, Fairbanks International Airport (FAI), FLL, Huntsville International Airport (HSV), MSP, PIT, and San Luis Obispo County Regional Airport (SBP). Five (9%) have a volunteer committee: Eagle County Regional Airport (EGE), Green Bay Austin Straubel International Airport (GRB), MCI, MSP, and Friedman Memorial Airport (SUN). None of these airports had both types of committees; a distinction was maintained between stakeholders and volunteers. Of the airports participating in the focus groups, LGB and EGE noted that they use volunteer groups within their airport arts program.

While none of the focus group discussions touched on stakeholder and volunteer committees explicitly, the topic of engaging community volunteers and stakeholders emerged throughout the discussions. IND tries to engage community members in various panels, and PIT consistently reaches out both internally and externally to support their stakeholders and create a greater sense of community.

3.2.3 Engagement and Involvement of Various Airport Offices and Personnel

The involvement of various offices and departments throughout the airport is essential for the operation of an arts program. Connecting the arts program to other airport operations facilitates collaboration, synergy, and comprehensive problem-solving.

Survey respondents were asked to identify their level of engagement with various departments and groups across the airport. A total of 58 respondents answered this question; 90% (n = 52) identified marketing as the department they engage with most, followed closely by airport executive leadership at 84% (n = 49), customer service or customer experience at 76% (n = 44), and facilities and maintenance at 71% (n = 41).

The focus group discussions highlighted that interactions are not necessarily as linear or as clean as the options available in the survey. For example, PHX and DEN both have positions that are technically filled by employees of the city; therefore, their engagement with executive leadership can be wider than airport leadership. See Table 7 for the level of engagement with other airport departments and operations reported by respondents.

Table 7. Level of engagement with other airport departments and operations.

| Airport Department/Operation | Engaged or Highly Engaged | Not Really Engaged | Don’t Know/Unsure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accounting (i.e., billing, invoicing) (n = 57) | 27 (47.4%) | 25 (43.9%) | 5 (8.8%) |

| Airport executive leadership (n = 58) | 49 (84.5%) | 8 (13.8%) | 1 (1.7%) |

| Customer service/customer relations (n = 58) | 44 (75.9%) | 7 (12.1%) | 7 (12.1%) |

| Information management (n = 57) | 13 (22.8%) | 30 (52.6%) | 14 (24.6%) |

| Maintenance/facilities (n = 58) | 41 (70.7%) | 15 (25.9%) | 2 (3.4%) |

| Marketing (n = 58) | 52 (89.7%) | 5 (8.6%) | 1 (1.7%) |

| Passenger operations (n = 58) | 25 (43.1%) | 26 (44.8%) | 7 (12.1%) |

| Security and safety departments (n = 57) | 23 (40.4%) | 28 (49.1%) | 6 (10.5%) |

A possible reason for the high level of engagement is that many arts programs reported being housed under the marketing department. According to the focus group discussions, executive leadership may have decision-making power as well as sit on several committees or boards, and customer service and customer experience often connect closely with marketing. Finally, considering the crucial role that facilities and maintenance were reported to play in the coordination of installation, upkeep, conservation, and removal of artworks, their high rate of involvement is expected.

Additionally, many of the focus group discussions emphasized the importance of relationships to facilities and maintenance. IND, PIT, and LAX noted how crucial maintenance and facilities were to their programs. Bradley International Airport (BDL), which has a young airport arts program, noted that implementation would not have even been possible were it not for the willingness and flexibility of the maintenance and facilities department. At EGE, terminal managers and maintenance managers make the primary arts program decisions.

Other departments that were mentioned in the survey included accounting at 47% (n = 27), safety and security at 40% (n = 23), and information management at 23% (n = 13). The safety and security department was mentioned in the focus groups. Security regulations and protocols at airports impact the types of artworks that can be performed or installed. For example, one focus group member mentioned security issues regarding performance artists who work in terminals and may need ongoing security clearance. Another focus group member discussed how certain installations may need to be located at a distance from security if it interferes with Transportation Security Administration (TSA) operations. For example, a painting at MCI was interfering with the TSA facial recognition program and needed to be moved as a result.

3.2.4 Policies and Procedures Explicitly for Airport Art

Policies and procedures serve as essential guidelines that govern the operations, behavior, and decision-making within an organization. They provide clarity, consistency, and structure to various processes and activities to ensure that all members understand their roles, responsibilities, and expectations.

Of the 55 airports that responded to the question, 29 (52.7%) noted that they have a set of policies and procedures that were explicitly written for their airport arts program. Furthermore, of the same 55 airports that responded, 20 (36.4%) have guidelines for airport arts program boards and committees.

PHX noted that they operate according to policies much like those at a museum (see Photo 6). However, that appears to be the exception. While PIT has some policies and procedures, most fall under the wider operating procedures of the airport. John Wayne Airport (SNA), LGB, and ALB noted that, while they have policies, they need to be revisited and updated. Both LAX and DEN highlighted that their previous policies had been established by the city entities. MCI, where the arts position was a city function until two years ago, is adapting city policies and procedures to align with the newly developed Arts Program Manager position.

The development of policies and procedures is dependent on the existing policies and procedures of various departments and functions throughout the airport. According to respondents, this situation can sometimes make the development of arts program policies and procedures difficult.

3.3 Key Goals and Documentation of Airport Arts Programs

Program goals and documentation provide clarity, direction, and accountability. By clearly defining the objectives and desired outcomes, key goals establish a shared understanding of what the program aims to achieve, and documentation sets the milestones and performance standards.

Among the 55 respondents to Question 12, less than half (41.8%, n = 23) had a clear mission statement or set of goals for the arts program. However, among the focus group attendees, some had established mission statements, for example:

- DEN: “The mission of DEN Arts is to engage, educate, and entertain the public audience.”

- LAX: “The mission of the Art Program is to present diverse and memorable art experiences to enhance and humanize the travel experience at LAX and the LAX FlyAway bus terminal in Van Nuys. Featuring local and regional artists through temporary exhibitions, permanent art installations, and cultural performances, the Art Program provides access to an array of contemporary artworks that reflect and celebrate the region’s creative caliber.”

- PHX: “The mission of the Phoenix Airport Museum is to enhance the Airport visitor’s experience by creating a memorable environment that promotes Arizona’s unique artistic and cultural heritage through an Art Collection, Exhibition Program, and Aviation History Collection.”

- PIT: “To manage an art program of style, diversity, and beauty to be enjoyed by our traveling public and employees that also promotes public art and enhances the airport environment.”

Among these mission statements are examples of the program’s purpose, the target audience, the core values of the arts program, the unique offering made by the program, and an aspiration for the art experience. Other focus group attendees publish statements on their websites that are similar in focus but are not explicitly identified as a mission statement. However, across all focus group attendees, the same sentiments are clearly conveyed as their sense of purpose and aligned with the focus group discussions about the history and impetus of the arts programs within their respective airports.

3.3.1 Strategic Plans/Master Plans

A strategic plan is a roadmap for a program’s future direction and success. It outlines the goals, priorities, and strategies over a defined period, typically ranging from three to five years. An airport strategic plan outlines the overarching goals, objectives, and priorities for the airport’s development, operations, and long-term sustainability. At the same time, an airport arts strategic plan specifically focuses on the development, management, and promotion of the airport’s arts program. It identifies goals and strategies for enhancing the artistic and cultural aspects of

the airport environment, such as curating art collections, integrating art into terminal spaces, engaging with local artists and communities, and fostering public appreciation and participation in the arts. Among 55 respondents to Question 12, seven (12.7%) have an airport arts strategic plan: BFI, Fayetteville Regional Airport (FAY), FLL, GRB, HSV, SAN, and SJC. The data suggests that hub size of the airport has not necessarily played a part in whether an arts program has a strategic plan. Most arts programs do not have a standalone strategic plan; however, PHX noted that their arts program is part of a larger airport strategic plan.

Alternatively, some airport programs or projects have an airport arts master plan that outlines a vision and strategy for integrating art into terminal spaces, curating art collections, engaging with artists and communities, and enhancing the passenger experience through artistic expression. This type of plan is different from an airport master plan, which is a comprehensive blueprint outlining the physical development and infrastructure of an airport facility, such as capacity expansion, safety improvements, environmental sustainability, land use, and economic development.

Among 55 respondents, eight (14.5%) [(DEN, Mahlon Sweet Field (EUG), FLL, MSP, PIT, RNO, SAN, SJC)] have an airport arts master plan, while another six (10.9%) [Asheville Regional Airport (AVL), FLL, Monroe Regional Airport (MLU), Philadelphia International Airport (PHL), SAN, Tallahassee International Airport (TLH)] have a plan that is part of the general airport master plan, which has a specific subsection for the arts program. During the focus groups, several respondents noted that they had a master plan or were in the process of developing a master plan specifically for the arts program. For example, RNO, BDL, and DEN have a standalone airport arts master plan. Meanwhile, even though the arts program at IND is mentioned in the general airport master plan, the IND arts program is developing their own master plan.

3.3.2 Budget Documentation

Almost half the survey respondents (n = 25, 45.5%) have a budget or a budget report for their arts program. Table 8 presents reporting budget documentation by airport size.

During the focus group discussions, budget documentation was mentioned; in many cases the conversation focused on funding sources that comprised the budget. According to the survey (n = 55), the most common funding sources for arts programs are capital development funds (n = 16, 29.1%), airport tenant rents and fees (n = 16, 29.1%), and passenger and facility fees (n = 12, 21.8%). Stillwater Regional Airport (SWO) receives state funding for the arts program, and PIT receives foundation funding.

The focus group conversations echoed the survey findings. Several respondents noted that they have 1% set aside from capital improvement funding, city appropriations, or the overall airport budget. MCI noted that the budget for art maintenance is handled separately and is sourced from tenant rental fees. Albert J. Ellis Airport (OAJ) in North Carolina noted that, although they do not have a budget, they hold small fundraisers to support their arts program and include funds raised in a narrative budget report to the airport.

Table 8. Surveyed airports with budgets or budget reports by size (n = 25).

| Airport Size | Number of Respondents with Budgets/Budget Reports |

|---|---|

| Large hubs | 7 (12.7%) |

| Medium hubs | 8 (14.5%) |

| Small hubs | 4 (7.3%) |

| Non-hubs | 6 (10.9%) |

3.3.3 Documentation on Maintenance, Conservation, and Deaccession

Among 55 survey respondents, 17 (30.9%) have maintenance or conservation documentation, and 17 (30.9%) have deaccession or removal documentation. Among the 55 survey respondents, 13 (23.6%) have both maintenance or conservation documentation and deaccession or removal documentation. Among the focus group participants, half the respondents (DEN, IND, LGB, MCI, PIT, PHX, RNO) mentioned policies and procedures for managing and handling maintenance, conservation, and deaccession. Alternatively, maintenance and conservation documentation may be part of the contracting documentation with an artist, while some airports, such as PHX and DEN, hire outside firms to help with various aspects of maintaining and conserving artworks.

3.4 Selection of Artwork in Airport Arts Programs

The selection of artwork in an airport environment is a complex process involving aesthetic considerations, concerns about space and scale, regard for the durability of art in high traffic areas, safety and security measures, accessibility concerns, and compliance or regulations.

3.4.1 Selection Processes

Seventeen survey respondents (30.9%) use a selection committee to help select their artworks. Responses range from the arts manager’s or director’s making the key selection decision to the arts manager’s or director’s not voting in the selection process. A common theme among some airports is the use of a city committee or local arts council for the selection process. In this case, there may be a request for proposal or similar request for art submissions with some established criteria, which would then be reviewed by the committee who chooses among art submissions. Two focus group participants noted that airport personnel sit on their selection committees, which is helpful because of their pragmatic considerations of the efficacy of the artwork and airport placement and sustainability.

One particular airport arts program of note is at OAJ. Small and unfunded, the program works with local schools and the local arts council to showcase local talent. The airport establishes a theme, such as “Flying in the Wind” (February 2024), and invites local schools and artists to participate. The selection of the art is conducted by the individual who manages the airport arts program and a few airport executives. In this case, the selected piece stays within the airport, while intermediary groups help to coordinate artwork and images to meet the theme (see Photo 7).

3.4.2 Considerations for Diversity of Artwork

According to survey responses (n = 55), 43 airports (78.2%) have temporary and changing exhibitions, while 32 airports (58.2%) have permanent and ongoing exhibitions. According to focus group participants, diversity among artwork is an important consideration. Diversity of artwork promotes inclusivity and representation and celebrates diverse cultures, perspectives, and experiences. Furthermore, artwork that reflects a range of backgrounds and identities helps create a more welcoming and inclusive environment, where individuals from different communities feel valued and represented.

Given the importance of artwork diversity, several airports have taken direct action to support greater diversity among their artwork. For example, DEN considers the diversity of both their artists and the decision-makers who select art pieces. They have enacted a policy requiring that at least 51% of selection committee members come from Black, Indigenous, and Persons of Color (BIPOC), and historically marginalized communities. MCI assesses their artwork, and currently

at least 50% of their collection is from the BIPOC community and at least 50% is from women artists. Both PIT and IND aim for greater representation in both their selection committees and in the artwork displayed. While LAX has a large number of international artists, their selection committee is community-centered and purposeful, seeking to ensure that they have diverse representation among their art pieces.

Focus group attendees also discussed objectionable or controversial artwork. Because art can be subjective, airport arts programs seek to find art that appeals to the widest range of passengers and personnel. In some instances, respondents discussed encounters with pieces that walked a fine line and were guided by clear criteria. In the two cases noted, both airports resorted to the guidelines established by their programs. While not perfect—in one case the objection led to an update of the policy—they do inform the decision-making process as to whether a piece is acceptable. A few airports acknowledge that some work may offend or upset, which cannot always be predicted. Therefore, many respondents advised setting guidelines for acceptable art in an airport environment.

3.5 Impacts of Airport Arts Programs

Measuring the impact of arts programs is valuable to the immediate and continued support of the program. By quantifying outcomes and assessing performance, programs demonstrate accountability to stakeholders, including funders and the community. Additionally, measuring programs highlights strengths, areas for improvement, and strategies for decision-making, including resource allocation. In short, measuring the arts programs at airports not only helps determine whether programs are meeting their mission, but also provides data and information for long-term sustainability.

3.5.1 Methods of Airport Arts Program Impact Measurement

Three (5.5%) of surveyed airports (n = 55) [(IND, PHL, St. Louis Lambert International Airport (STL)] have impact or assessment reports regarding their airport arts program. Additionally, three (5.5%) airports [Columbia Regional Airport (COU), FAY, IND] currently measure economic impacts. None of the focus group participants had a separate arts-focused assessment, although PHX has tried surveys in the past. A few respondents noted that surveys were part of larger, airport-wide surveys or point-in-time gate surveys, in which the impact of the arts on passenger experience was included as one or two questions. Two airports, PHX and ALB, implemented a guestbook/comment book and, as a result, could collect some qualitative data. A respondent from DEN noted getting “information from the demographic surveys that we require from panelists and from artists that I think kind of inform how our program is doing.”

PIT respondents noted that they have anecdotal data from artists who inform them when they have been contacted or see an uptick in their media traffic as a result of being on display at the airport; however, they noted that anecdotal data was not consistently retained and therefore could not be a reliable metric. Additionally, LAX respondents noted that they pay close attention to social media and look at interaction levels. Overall, it was noted by several respondents that arts program impact was not something methodologically or consistently captured and measured; several noted they were unsure whether it could be measured.

Although some survey respondents measure or track some impacts, an online search of airport websites did not yield a set of measures or indices that these airports are using, nor did it provide a methodology demonstrating how these data points are being collected. See Table 9 for current impact measures tracked by survey respondents.

Although limited established measures track the impact of the arts among airports, survey respondents were asked a series of questions about the impact of their arts programs. Of the 51 survey respondents who answered the questions, all agreed or strongly agreed that their airport arts programs contribute to a positive customer experience. Furthermore, among the same 51 respondents, all but one airport agreed or strongly agreed that their airport arts programs create a sense of place and are important to their airports. More than 90% of respondents felt that an airport arts program creates a sense of home for local travelers (n = 49, 96.1%), creates a relationship between the airport and the local community and stakeholders (n = 49, 96.1%), and has a social impact (n = 47, 92.2%). Less than half (n = 21, 41.2%) believe that the airport arts program has had an economic impact, which suggests that, even without significant empirical data for any specific airport, they believe that airport art enriches the airport through enhanced passenger experience, increased community involvement, and amplified airport identity. Given the limited established measures to track the impact of the arts among airports, this topic is explored in greater detail as a suggestion for future research in Section 5.3.

According to the artist, Kat Owens, Portrait of a Sperm Whale was hand-sewn with plastic debris (see Photo 8).

Table 9. Current impact measures tracked by survey respondents (n = 53).

| Impact Measures | Number of Airports that Track Data |

|---|---|

| Economic impacts | 3 (5.7%) |

| Social impacts | 10 (18.9%) |

| Customer engagement | 16 (30.2%) |

| Cultural appreciation/awareness | 13 (24.5%) |

| Airport identity | 8 (15.1%) |

| Educational impacts | 6 (11.3%) |