An Introduction to Economic Systems as a Structural Driver of Population Health and Exploring Narratives and Narrative Change: Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief (2024)

Chapter: An Introduction to Economic Systems as a Structural Driver of Population Health and Exploring Narratives and Narrative Change: Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief

|

Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief |

An Introduction to Economic Systems as a Structural Driver of Population Health and Exploring Narratives and Narrative Change

Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief

AN INTRODUCTION TO ECONOMIC SYSTEMS AS A STRUCTURAL DRIVER OF POPULATION HEALTH: A WORKSHOP SERIES

On March 18, 2024, the Roundtable on Population Health Improvement hosted a workshop to introduce its new strategic focus on Elevating Structural Drivers of Population Health,1 starting with the exploration of economic systems throughout 2024. Roundtable cochair Ana Diez Roux, distinguished university professor of epidemiology and director of the Urban Health Collaborative at Drexel University, defined the structural drivers as the components, organization, and rules of the systems that produce and sustain levels of health and the distribution of health through social relationships, history, policies, practices, beliefs, and norms. She added that the roundtable’s exploration of the structural drivers will include implications for scientific understanding, actions, and solutions. Diez Roux moderated a discussion with Nancy Krieger from Harvard University, Darrick Hamilton from The New School, and Amanda Janoo of the Wellbeing Economy Alliance, who also offered additional remarks related to the workshop series’ focus areas on narratives, partnerships, and democracy.

Krieger said it is of paramount importance to analyze economic systems and how they are structured by relations of power. Those power relations influence the economic priorities of policymakers who oversee these systems, ultimately reinforcing ideologies, such as eugenics and racism, that perpetuate disinformation and inequities. Diez Roux said that since the social determinants of health concept became mainstream, it has lost power and its connections to systems and structures. She asked about different approaches to elevate processes and explanations. Krieger provided an overview of the legacy of social determinants of health and emphasized the importance of acknowledging the history of political and economic arguments about these related terms and constructs. She said the important questions to ask are, “Who is the economy working for?” and “Who is it harming?” She added that population health scientists still have a lot to learn from other scientists (e.g., political scientists) on how to frame structure and agency.

Hamilton centered his points on the relationship between the political economy and identity group stratification—“who we think is deserving or undeserving based on cursory identities like gender, race, [and] immigration status.” Questioning the purpose of an economy and the role of government policy and policy decisions, he said economics goes beyond the domains of health and wealth, and “every policy and structure has been racialized.” Hamilton added, “government has proactively

__________________

1 See https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/elevating-the-structural-drivers-of-population-health-a-workshop-series (accessed September 23, 2024).

shaped our economy, determining who reaps benefits of prosperity.” Hamilton discussed the physical and mental health harms of the “bootstrap” narrative, which frames personal responsibility—that is, individual agency and self-investment, such as obtaining higher education—as the pathway toward upward mobility. He explained how this false narrative also casts poverty and inequality as the result of unproductive and deficient behavior, linking poor outcomes to personal choices. Hamilton provided potential solutions to achieving economic agency, including promoting collective narratives, movement building, and resource sharing. He concluded by saying the purpose of an economy is to promote productivity, advance human flourishing, and empower righteous ways; the role of government is to set rules and steward public resources for self-determination. Diez Roux asked about the implications of questioning an economy’s purpose and having that question taken seriously. Hamilton responded that the “why” of an economy is rarely discussed in scholarship and that an economy is a political construct devoid of an analysis of power.

Janoo pointed out that investigating how the economy affects health is an important shift from decades of measuring economic and societal success by the level of economic growth, or gross domestic product (GDP).2 Janoo suggested using a well-being framework to help align different actors and disciplines to work collectively toward health, equity, and sustainability. She defined the economy as a method of interacting with one another and the natural environment by producing and providing. She reiterated that an economy’s goal is ideally to improve quality of life for all. She discussed the Wellbeing Economy Governments partnership, a collaboration between the governments of New Zealand, Iceland, Finland, Scotland, Wales, and Canada, who share transferrable policies and practices to build well-being economies.3 She concluded with examples showcasing the uptick in movements, initiatives, and advocacy in this domain, which add to the evidence of a shift toward a well-being economy. Janoo explained that social connectedness is a key measure of economic prosperity, and the epidemic of loneliness and isolation is an example of the economy not working. She also referenced recent neuroscience research that suggests people are wired to give and share. The ability to imagine a different system shows a shift happening, she said, and now is a pivotal time to frame a well-being economy.

Discussion

Marc Gourevitch, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, asked about the role of movement building. Krieger said there is a need to move away from methodological and biological individualism and essentialism and to think about where to challenge false ideologies like scientific racism, eugenics, and white supremacy. Hamilton added that priorities should be kept clear and simple and should learn from the past, referencing the COVID-19 pandemic. Janoo noted there are movements of holistic transitions that can be seen at all levels and highlighted the work in Washington state for developing a ten-year poverty alleviation strategy.4

Sheri Johnson, University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Medicine and Public Health, asked speakers for examples of data linking health outcomes to economic systems. Hamilton referenced evidence that suggests socioeconomic status and education are strong predictors of health. He also explained how economic systems influence the overall socioeconomic conditions that affect maternal and infant health, such as resource allocation, access to health care, inequities built into these systems, and public health policies. Krieger said it is important to understand the varieties of capitalism, socialism, and communism, adding that democracy and knowing who has political power are crucial to improving health outcomes. Janoo referred to the literature linking spirituality to public health outcomes and noted the connections between inequality, violence, and mental health disorders. Janoo added that the Planetary Health Alliance is exploring the intersection between well-being and nature and provides space to build a regenerative economy.

Philip Alberti, Association of American Medical Colleges, asked about metrics that matter. Janoo reiterated that the GDP is the wrong measurement for economic progress and said most countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development5 have an alternate

__________________

2 See https://www.bea.gov/resources/learning-center/what-to-know-gdp (accessed August 2, 2024).

3 See https://weall.org/what-is-wellbeing-economy (accessed August 2, 2024).

4 See https://dismantlepovertyinwa.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Final10yearPlan.pdf (accessed August 2, 2024).

5 See https://www.oecd.org/en/countries/united-states.html (accessed August 15, 2024).

well-being indicator. She emphasized the importance of developing metrics now with the understanding that the data methods can be refined later. Krieger suggested taking a structural approach to developing metrics and said that future data collectors should inform individuals, neighborhoods, and communities about why this information is being collected. Hamilton said data collection is valuable to look at generational shifts that can be linked to policy, but an infrastructure is needed to address inequities.

This session concluded with audience questions about how to strategically communicate the benefits of an economic paradigm shift, including how to measure wealth differently. Hamilton suggested adopting a collective vision to commit to without compromising. Krieger added that collective action and change can shift political power dynamics, influencing regulations and legislation on benefits, exposures, and taxation—where benefits refer to economic advantages, and exposures to risks and vulnerabilities affecting individuals or communities. She also said messaging is not the only problem and pointed to structural power inequities. Janoo added that the first step is reconceptualizing achievable progress and redefining what economic activities contribute to thriving communities. Janoo referenced the five core principles at the Wellbeing Economy Alliance—passion, trust, care, togetherness, and equality—and said that in addition to wealth and income, time, voice, and power also need to be redistributed more fairly. Hamilton said the primary link to wealth is access to “something that is nondepletable, that offers a return in perpetuity, [and] that people can” collectively share. Given that societies define assets differently, he provided examples of collective and individual assets, such as free public education and baby bonds, respectively. The last question asked about the role of unions in reshaping our economic system. Krieger reiterated the need to consider structural rules that allow unions to exist and added that states have regulations for workers, regardless of unionization. Hamilton said unions are not immune to structures that might be detrimental to society.

Mary Pittman, roundtable cochair and emerita president and CEO of the Public Health Institute, provided closing remarks. She noted that it has taken a long time for the concept of social determinants of health to change the narrative and the way research is conducted and that these shifts have also required intersectoral work.

EXPLORING NARRATIVE AND NARRATIVE CHANGE

On June 27, 2024, the Roundtable on Population Health Improvement hosted part II of the workshop series on Elevating Structural Drivers of Population Health. Pittman provided a summary of part I,6 which discussed how beliefs and ideologies such as racism and eugenics in the U.S. have shaped economic priorities and affected health outcomes. Pittman introduced the focus of part II: narrative shift and culture change pertaining to economic systems and the implications for health and well-being.

Perspectives on Political Economy and Its Narratives

Tiffany Manuel, founder and CEO of TheCaseMade, moderated the first panel, exploring the relationship between systems and narratives and the implications for health and well-being. She framed the discussion by describing the role of language, stories, and narratives in decision making; the evolution of messaging; and the need to replace false narratives. She introduced speakers Trevor Smith, cofounder and executive director of the BLIS Collective,7 and Jess Zetzman, director of messaging and content at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Manuel gave examples from her work showing how the economic system is not working for average people: the Great Resignation, deteriorating transportation and infrastructure, and the economic burdens caused by segregation and redlining are costly. The American Dream narrative is tied to homeownership, but “we are literally a nation of renters,” she said. She asked Smith and Zetzman for examples of dominant narratives that are outdated or that serve as barriers toward upward mobility. Zetzman named American exceptionalism—the deservingness and individualism mindset, which says that “you having access to quality health care somehow means that I will not.” The “all-one-race” narrative implies disparities do not exist because of race. Smith agreed that the biggest problem for the U.S. is the value of individualism (in contrast to collectivism): “folks do not see their

__________________

6 See https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/42275_03-2024_economic-systems-as-a-structural-driver-of-population-health-introduction-to-workshop-series (accessed September 23, 2024).

7 Black Liberation-Indigenous Sovereignty. See https://www.bliscollective.org (accessed August 4, 2024).

freedom bound up in others, and folks see their economic success as being solely based on how much money is in their bank account, as opposed to seeing their neighbor also thriving.” He also introduced the narrative of racial progress, an illusion that overstates efforts to address historical racism. It is not about increasing the number of Black billionaires, he said, but about creating a more collective culture where wealth is more equally distributed across society. He also mentioned the attacks on diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts, affirmative action, and reparations efforts as manifestations of the all-one-race narrative. Speakers further discussed how narratives can be interconnected, cause harm, and foster stigma.

Manuel said shifting narratives takes time but is urgently needed. Giving the example of the American Dream, which is used by many people and policymakers to appeal to a shared understanding, she said that in reality, the narrative has been proven false, including by the research of public economist Raj Chetty. She asked speakers how to navigate this challenge. Smith said narrative work cannot be divorced from community movement building and organizing. He emphasized the importance of meeting people where they are and fostering participation to move policies forward. Zetzman suggested developing a vision for the future that is possible and disseminating solutions instead of continuing to admire the problem. Manuel asked what is working well in terms of narrative change. Zetzman mentioned an increase in systemic thinking (i.e., understanding how systems shape the conditions in which people live, work, and play), and Smith described the progress in his work of advocating for reparations. Manuel added that increased cultural awareness is important to storytelling, that there is a sense of hope in younger generations, and ultimately, narrative work has the power to bring different sectors together.

Diez Roux asked how science can contribute to narrative change. Zetzman reiterated changing the focus to interventions and solutions instead of continuing to admire the problem. Smith said researchers and scientists can partner with local advocacy groups and help inform and apply research through intentional storytelling. Science can also help by considering strategies to measure the benefits of narrative change, he added. Manuel emphasized that disseminating data is not enough and that scientists have a responsibility to share information, especially if it is aspirational.

Hilary Heishman from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation pointed out how one narrative rarely fits all and asked how best to consider the variety of narratives available. Smith said to start with larger systems that reach everyone across age, race, and class, such as social media, mass media, and pop culture. He also said to start with relatable narratives like the resurgence of the labor movement and the narrative around the 1 percent.8 He also suggested breaking down silos and encouraged collaboration. Zetzman mentioned work from the Narrative Observatory9 and outlined strategies for delivering story opportunities to values-based audiences—groups connected by shared values and ideal for targeted marketing. She emphasized the importance of incorporating diverse voices to create a powerful and cohesive narrative.

A virtual participant asked about the success of these approaches in shifting specific narratives. Smith brought up marriage equality, legalizing marijuana, the death penalty, gun violence, the importance of essential workers during the COVID-19 pandemic, and reparations as movements where we have seen a narrative shift over time. He added how the murder of George Floyd led to an uprising of civil unrest, which opened opportunities for social justice, such as pushing to change the name of the Washington, DC football team. Zetzman added the race-class narrative10 as a good example as shifting the narrative. Manuel added that many people now understand their zip codes as a predictor of health. A virtual participant asked about the use of artificial intelligence (AI). Manuel said an important challenge to consider is how to identify credible information to deter the spread of misinformation. Zetzman added that building trust with credible messengers is part of narrative shift. Smith pointed out that minoritized groups are often left behind

__________________

8 See https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3489365/ (accessed August 6, 2024).

9 See https://narrativeobservatory.org/ (accessed August 6, 2024).

10 The race-class narrative is a communication strategy that combats the use of covert racism and builds cross-racial solidarity to mobilize action for policies and changes that promote economic and racial justice for all. See https://www.wemakethefuture.us/history-of-the-race-class-narrative (accessed August 27, 2024).

when generating AI, and as this field grows, AI should be used to address disparities, not add to them.

Bobby Milstein from ReThink Health asked if the idea of pragmatism is a priority among change makers. Smith said, “pragmatism is in the eye of the beholder”; for example, reparations may not be seen as a pragmatic solution across society, but, “if we look back through history, those who were seen as radical were actually on the right side of history.” Zetzman said, “We want to cast this vision, we want to show that [it is] possible, that there is a pragmatic way of getting there, counter cynicism, and share solutions.” Manuel concluded by encouraging participants to think about the role they themselves can play in storytelling.

The Role of Narratives in Research

In the second session of the workshop, Gourevitch moderated a discussion focused on evidence-based research examining the relationship between economic structures and health, and on strategies for narrative change that can develop those structures. Gourevitch introduced panelists Joe Grady from Topos Partnership and Kosali Simon of Indiana University.

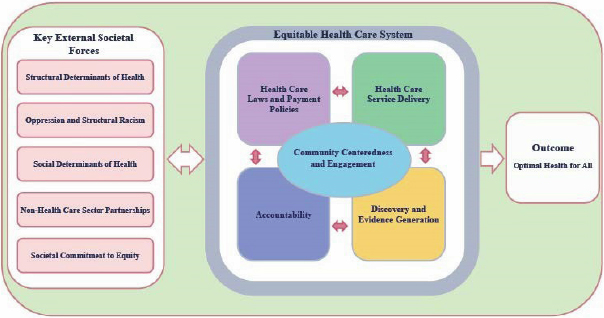

Simon discussed leveraging economics to improve population health equity. She emphasized that the “economy is us, it is what we make of it,” and it provides a framework for allocating resources within a society. The government’s role includes stepping in and making corrections, and Simon listed the many reasons markets and solutions might fail. She also said government action is not the only solution, but “there may be solutions that the markets themselves produce” and gave the example of Daraprim, a medication whose patent expired, and for which a separate company entered the market to produce a reasonably priced generic. Focusing on inequities, Simon said, “from the start of time, resource distribution has been unequal,” and discussed the supporting research. She questioned how equity fits into a system driven by individual objectives and highlighted Ending Unequal Treatment Revisited,11 a study conducted by the National Academies, which provides a framework to achieve optimal health for all, illustrated in Figure 1.

Source: Presented by Kosali Simon on June 27, 2024. NASEM, 2024.

Grady discussed what research says about building and adopting narratives that can connect economics with health and support system-level changes for health and well-being. He started with an overview of the Topos Partnership,12 which is focused on narrative change and uses cognitive and social science alongside public opinion and political strategy, as well as research approaches such as media narrative review, ethnography, message testing, qualitative, and quantitative methods. Grady explained “cultural common sense” as broadly shared narratives that guide conversations, influence policy choices, and drive action—across demographics. He said that patterns of “default thinking” and dominant narratives, often shape perspectives regardless of people’s individual circumstances. This applies to how the economy is viewed, which is typically very business-centric, he said. Topos Partnership has found Americans have a strong skepticism about whether policy is ever a solution and are reluctant to talk about race. These defaults also obscure the role of health and equity in the economy.

Grady shared patterns and trends that his organization has found relate to people’s thinking about health and economy. For example, there is a cultural common-sense awareness that stress impacts health—including acknowledgement that some groups experience more stress than others, leading to different health outcomes. Place—and how policies change aspects of places to promote or hinder health—is another helpful touchpoint to help move people away from individual mindsets and toward thinking about what could matter to everyone. It

__________________

11 See https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/27820/ending-unequal-treatment-strategies-to-achieve-equitable-health-care-and (accessed September 23, 2024).

12 See https://www.topospartnership.com/ (accessed August 8, 2024).

is important to create narratives or messages that “feel like common sense,” he said.

Gourevitch started the discussion by asking the panelists if they believed people have an inherent predisposition to preferencing individual narratives over collective narratives. Grady said Americans strongly emphasize individual narratives, though cultures vary. Gourevitch asked Simon about the distinction between the economy and political economy and how this affects narrative. Simon said the political marketplace is where decisions are made by elected officials and framing a narrative can help support certain solutions. In his organization’s work, Grady said, one of the biggest challenges is helping people feel like they can make a difference. He explained that people have a basic sense of political economy, and the dominant narrative is that “everything is rigged against them by rich, powerful people.” Providing examples of where positive change is possible and where public action can make a difference is an important element of shifting the dialogue, Grady added.

Gourevitch asked speakers about capitalism and its role in a healthier economy. Though Topos Partnership has not conducted interviews directly about capitalism, Grady said he has seen conservatives acknowledge issues related to the economy when examining health inequities. Simon pointed out that the word “capitalism” is not associated with positive benefits and emphasized that preserving individual autonomy involves recognizing inequity. Gourevitch asked if there is an alternate framing to describe economic structures that would be more productive for health and equity. Simon recommended identifying starting points where a consensus can be formed. Grady said the words “guardrails” and “protections” have often proved helpful in his work when discussing common sense in the economic landscape. The majority of people said they do not want an economy without any guardrails or protections. “Guardrails” was used broadly to mean anything from regulations to steering legislators toward the public interest, and a majority of people do not want an economy with no guardrails. “Protections” could apply to a range of issues, from air pollution to child labor. Diez Roux emphasized the importance of understanding how the system of capitalism works to create a social movement for change.

Audience member Jessica Kirchner, senior policy analyst for the children and families team at the National Governors Association, said her work has found that narratives are more effective when tailored to geography, using New York and Alabama as an example of contrasting opinions. Kirchner asked speakers how to change the narrative for the people who drive policy and change. Grady said identifying the core of the conversation will help align priorities. He added that this organization works at the national and local level to find common conversations across geography and has found commonalities between New York and Alabama opinion. A virtual participant asked how environmental justice could be framed to help advance health equity. Grady suggested including commonsense explanations and examples of how different communities are impacted by activities like industry, highway construction, to more effectively highlight the need for change and action.

How the Economic System Affects Communities and Workers and the Role of Narratives

Monica Valdes Lupi, managing director of health at the Kresge Foundation, moderated the third panel, on how the economic system affects communities and workers and the role of narratives in this relationship. Valdes Lupi opened by speaking about the generational disinvestment that has resulted in a lack of resources for many communities and about policies and programs that intentionally barred Black, Indigenous, and other people of color populations from wealth-building opportunities. She noted how the harms of disinvestment are seen in current health inequities and explained that one focus of the Kresge Foundation has been creating community investment ecosystems aimed at closing the racial wealth gap. To do this, Valdes Lupi said the foundation deploys “mission-driven capital” to invest in “community defined priorities.” She stated that narrative change is an important crosscutting strategy to achieve success in these efforts and shared the example of how Kresge has partnered with Metropolitan Group to develop a messaging framework for advancing racial justice, social justice, and health, responsive to the needs of the foundation’s Climate Change, Health, and Equity Initiative grantees. This panel discussion, Valdes Lupi said, would highlight the work of building new narratives around inclusive economic policies.

The first panelist was Saru Jayaraman, president of One Fair Wage and director of the Food Labor Research Center at University of California, Berkeley. Jayaraman said she has been organizing restaurant workers for the past 22 years and was speaking from Phoenix, Arizona, where she was working with restaurant workers to get wage increases on the ballot. She explained how in these post-pandemic conditions, the U.S. low-wage economy is in a moment of both crisis and “incredible worker power,” particularly among restaurant workers. Noting that the restaurant industry is the largest and fastest-growing private sector in the country, Jayaraman emphasized that it has historically been the lowest paid, which contributes to its large role in determining the economic stability of low-wage workers. Providing some historical background, she discussed how restaurant workers before emancipation were primarily White men, after which the industry sought cheaper labor among Black populations. She also spoke about the National Restaurant Association, a corporate trade lobby representing restaurants that was established in 1919 and that has been working since then to keep worker wages low by arguing that wages are paid by customers through tips. Jayaraman stated the current federally mandated minimum wage for tipped workers is only $2.13 per hour.13

Jayaraman highlighted the importance of recognizing throughout the day’s conversations that there are people who have “purposely driven economic inequality,” severely affecting population health. Jayaraman also mentioned how it is important to recognize not only how the economy impacts health but also how health impacts the economy, and she highlighted the COVID19 pandemic as an example. During the pandemic, six million restaurant workers lost their jobs, and two-thirds reported not qualifying for unemployment insurance because their wages were too low, she continued. As a result, Jayaraman explained that many workers were forced to return to work before it was deemed safe to do so, and 12,000 workers died due to workplace exposure to COVID-19. She also said that during the pandemic, workers experienced increased harassment and economic instability; women workers were regularly asked by customers to remove their masks so their physical appearance could be used to determine the tip. Jayaraman reported that these negative experiences caused 1.2 million restaurant workers to quit.14 Highlighting worker power amid these experiences, she stated that with support from the Gates Foundation, One Fair Wage tracked approximately 6,000 restaurants that increased wages as a result of worker voice and launched the 25 by 250 campaign, an initiative moving ballot measures in 25 states to raise wages by 2026 (the 250th anniversary of the U.S.), with recent victories in Chicago and Washington, DC.15 Jayaraman said these successes are part of what has been the most transformative progress in narrative shift to date, after years of effort, demonstrating that narrative change must be worker driven. She noted how when workers’ voices and efforts lead to policy change, their success inspires others to engage in the work. Jayaraman closed her remarks by emphasizing that workers’ demand for more is occurring—not coincidentally—alongside an increase in the cost of living and that the cost of living and need for jobs with living wages is the major issue among Black, Latine, and young voters this election year. The demand also highlights, she said, the distinction between “the economy” and “my economy” and how stories of lived experience can show great hardship even if national rhetoric claims the U.S. economy is strong.

The second panelist was Robert Blaine, senior executive and director of the Center for Leadership, Education, Advancement, and Development at the National League of Cities and former chief administrative officer of Jackson, Mississippi. Blaine spoke about his experience in Jackson and how in his position, he observed how the level of government closest to communities can be the most responsive. He said his work both in Jackson and at the National League of Cities is focused on investing in community voice, including a deeper focus on who is part of that voice, to ensure that the work is reflective of needs. Blaine stated that “equity envisions a world where un-deservedness is disrupted as a part of the social contract” and is about creating an “egalitarian, harmonious, and compassionate society.” Elaborating on the

__________________

13 See https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/state/minimum-wage/tipped (accessed August 23, 2024).

14 For more information, see https://www.npr.org/2021/07/20/1016081936/low-pay-no-benefits-rude-customers-restaurant-workers-quit-at-record-rate (accessed August 14, 2024).

15 For more information, see https://www.onefairwage.org/states (accessed July 31, 2024).

narrative of un-deservedness, which he described as the idea of who is deserving of investment, Blaine said it can be countered through development of a floor “through which people cannot fall.” He also acknowledged four important components of an economic model for human dignity: affordable housing in safe communities, a thriving education system, work opportunities, and foundational infrastructure. Sharing an example from his time as chief administrative officer of Jackson, Blaine explained how he valued participatory budgeting, a process that gave residents a voice in the city’s budget.16 He said to do this effectively, he created a board game both to educate people on how a budget gets allocated and to gather input on priority issues. Using the previous year’s budget and real issues that had occurred, Blaine said the board game showed the community the challenges around how much of the budget was feasibly available for use. He reported that the priorities identified by community members who played the game were aligned with activities in the new budget year.

Blaine introduced the term “egalitarian democracy” to denote a democracy that truly focuses on need by investing and working with communities. He noted that in Jackson, the Local Infrastructure Hub was created to support small to mid-sized communities in accessing funds in the city budget by teaching them through an online curriculum how to write competitive applications; the program resulted in a 40 percent increase in these communities’ winning the money. In closing, Blaine emphasized the importance of creating an “economic model of human dignity” and expanding these efforts across the U.S.

As the panel transitioned to questions, an attendee from the virtual audience asked what is needed to move toward federal legislation for wage increases and how to ensure these efforts are worker-led. Jayaraman said federal legislation will likely only happen if the National Restaurant Association is defeated in at least half the country. Regarding workers leading, she emphasized how the “workers demand more” narrative has shown to be more effective than the “workers deserve more” narrative and said narrative change has never been more transformative than since workers began advocating for themselves. Valdes Lupi asked Blaine if he could speak about aspects of his work that might seem incongruent but that are connected to healthy communities. Blaine spoke about the people’s assemblies in Jackson—neighborhoods coming together to hold government accountable.17 He shared the example of when the city developed a plan to save the public school system from state control by initiating a door-knocking campaign to gather recommendations from the community. This was a “moment of true community engagement,” Blaine said, in which people shared support for a common goal and worked collaboratively to achieve it, ultimately retaining control of the school system.

An online attendee asked Jayaraman whether food service employers should provide insurance for all employees who work at least 12 hours per week as well as how altered business hours, which became common after the pandemic, have affected workers. Jayaraman first noted that the decrease in business hours was not a voluntary action by employers but rather the result of not having enough employees to cover all shifts, with the decrease in workforce spurring an overreliance on tips rather than wage increases. She said that large corporations should provide insurance to employees but emphasized that their reluctance to do so is not due to the nature of the economy. She expressed frustration with how the economic system is not illustrative of free market capitalism but rather is controlled by corporations and trade lobbies. Returning to the example of insurance, Jayaraman highlighted how the restaurant industry limited workers to 39 hours per week so that they would be ineligible for health exchanges under the Affordable Care Act.

Meg Guerin-Calvert of FTI Consulting asked both speakers to expand on how initiatives such as the ones they presented could be replicated and on how to sustain engagement. Blaine said the sustainability of an initiative is something to discuss at the start, given that typically a crisis prompts action, but the action is not usually aimed at addressing the root cause of the problem. It is important to conduct root cause analysis and consider the

__________________

16 For more information about participatory budgeting, see https://www.govocal.com/guides/beginners-guide-to-participatory-budgeting (accessed September 10, 2024).

17 For more information about Jackson, MS and the People’s Assembly, see https://hri.law.columbia.edu/mayor-chokwe-antar-lumumba-shares-his-people-centered-approach-economic-justice-jackson-ms-candid (accessed September 10, 2024).

mechanisms that will create long-term systemic change from initial programmatic level efforts, he continued. Blaine called this a “tiered impact model” and noted that systemic change should aim for population-level impact. Jayaraman added that there are two goals in organizing efforts: to win and to increase the number of people engaged in the fight. She described this as a widening spiral process that moves through the stages of current fights, stepping-stone fights, milestone reform, and long-term agenda, and that ultimately creates a cohort of people who have the capacity to continue.

Sheri Johnson reflected on how the narratives of deservedness and dignity relate to the economic system and asked whether countering these narratives requires a radical shift in power with development of a new economic system, or if smaller actions could be effective. Blaine stated the issue needs more than just “tweaking at the edges”; disruption of the current power structure in a way that creates an “egalitarian democracy,” where power is given to communities, would be an effective approach. He expressed desire for people to reclaim their power in government, saying “power is not given up, it’s taken.” Jayaraman also reiterated the power of the National Restaurant Association with two examples: the association told one senator that it could not vote for an initiative to raise wages, and the money that workers pay for food safety training is often used without their knowledge to lobby against them—a form of forced wage suppression. She said that her experience of personal harassment in her work has become a severe issue. Johnson asked Jayaraman how she would characterize the current U.S. economic system; she replied, “an oligarchy,” controlled by trade lobbies and corporations.

A virtual attendee was interested in lessons the speakers have learned through their experiences working on the ground. Over the past couple of years, Jayaraman shared, she has learned to follow where workers lead because dramatic changes can come from workers themselves demanding more. Blaine said he has learned that residents are the experts in their experience and their expertise must be relied upon. The final question for this panel was from an online attendee who asked how to begin building the foundation for multi-issue organizing and community-led efforts if these are not already established. Blaine provided an example from National League of Cities—the Early Childhood Success Team, a partnership focused on shifting power to community and strengthening the reading level of third graders by bringing together organizations to focus on kindergarten preparedness. The goal, he explained, was to invest in parents and equip them with the tools needed to advocate for their children and ensure access to the resources they needed to thrive in their education. Jayaraman added that it is important to have spaces and organizations that are solely led by those most affected by the problems they are aiming to solve. Furthermore, she said although having mayors, health commissioners, and leaders who take community input seriously is important, it is equally important to build the base of people to continue the movement after those leaders leave.

Economic Narratives from a Policy and National Perspective

Bobby Milstein moderated the final panel of the workshop, which included Van Freeman, senior director of policy and public affairs at Young Invincibles. Milstein introduced the panel’s focus, which was to examine the following questions:

- Who are the actors currently engaged in narrative change work?

- How can we bring more people together to grow the effort?

- How do we build the narrative needed to demand an economy that is more efficient at promoting well-being?

- What will it take to move toward the future that we envision?

He turned the discussion to Freeman, who provided background on Young Invincibles, stating that the organization started in 2009, was initially galvanized around health care access, and since has expanded into issues around workforce and higher education, particularly issues important to young adults such as livable wages and affordable education.18 He shared a story from his previous organizing work in Ohio, from a day when he was working with a young medical student, and they met a woman sitting on her porch in a medical wheelchair. He told the student it was important to hear her story,

__________________

18 For more information, see https://younginvincibles.org/ (accessed July 31, 2024).

because if the health care reform they were developing could not benefit her life in some way, then they would know they were not making progress. He told the student it is critical to connect policies to the people they will affect. Milstein asked Freeman how the interface between lived experience and policy work happens in his work at Young Invincibles. Freeman shared a video about Young Invincibles and the Healthy Minds Checklist, a list of services and resources institutions should be offering to provide mental health support to college students in Colorado.19 The initiative, he explained, was strengthened by young people who drew upon their own experiences to explain why mental health should be treated as a component of general health. Freeman highlighted how young people recognize the importance of healthy minds in creating the conditions for people to thrive in all aspects of life and how these improvements in personal well-being benefit communities and the economy. He spoke about the importance of amplifying lived experience and connecting it to policy, as well as collaborating with a diverse group of stakeholders throughout the process.

Milstein asked how Young Invincibles stays cohesive as an organization when tackling a variety of issues. Freeman said it is about focusing on young adults’ voices and lived experience because those reveal the issues most important to address. For example, he discussed how student loan debt relief is one of these critical issues, because the burden of debt prohibits younger generations from taking a more active role in society and influences personal decisions such as marriage and homeownership. Further describing this challenge, Freeman stated that those with student debt who choose to marry will likely see their loan payments increase. Without sharing personal narratives and hearing stories from people with lived experience, the severity of this issue will fail to be widely understood, he continued. Next, Milstein asked how these issues can be meaningfully translated to policy makers. Providing lived experience, Freeman said, “gives color and clarity to data they might be seeing” and offers a new vantage point. Finally, Milstein elevated the role of courage in this work and asked Freeman to highlight some signs of courage and optimism in the face of challenges. Freeman responded that the work involves taking on difficult issues with a degree of invincibility—“to stand up there and tell your authentic story”—while recognizing that change will not happen immediately but through perseverance, and speaking authentically through sharing stories about how issues are affecting well-being.

Transitioning to questions from the audience, Mary Pittman, cochair of the roundtable, shared her thoughts that although student debt forgiveness is strongly debated across sectors, the narratives and stories about how debt affects those experiencing it are not being told. She asked Freeman if he could speak more about how Young Invincibles aims to tell the story. Freeman explained that Young Invincibles works with young adults to share their stories about how student debt impacts their ability to engage more meaningfully in society. He said they do this by strengthening and honing young people’s communication skills to allow them to effectively articulate not only their experience but how their narratives connect to policy changes. Effective communication helps “connect the dots,” Freeman noted. Roundtable member Tiffany Manuel asked whether Young Invincibles is connecting its work to baby boomers, who are experiencing unique but similar existential threats, such as social security concerns and access to Medicare programs and health care, as well as the shared challenges of housing affordability and workplace issues. She highlighted how the same policies affect both generations, albeit sometimes in different ways, and that some argue the generations are dependent on each other (for example, baby boomers paying school taxes and younger generations paying into social security). Manuel was interested in whether there is a way to leverage this interconnectedness that creates solidarity rather than more division. Freeman responded that Young Invincibles works to grow the financial literacy of young adults and aims to reach a middle ground and listen to the perspectives of everyone, both young and old. Manuel followed up by asking Freeman how to build narratives of solidarity between young and old and whether there are signs of this happening. Freeman stated he does see signs of those experiences but acknowledged that Young Invincibles works primarily on the workforce and health care front rather than on housing issues. Speaking about workforce issues, Free-

__________________

19 The video can be viewed here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_awhR-US140 (accessed July 31, 2024).

man said Young Invincibles thinks about how to train both young and old for jobs. Milstein concluded this panel by noting how this discussion offered a new way of crafting policy design and moving beyond the narrative that singular solutions are needed for singular problems.

Closing Remarks

In her closing remarks for the workshop, Ana Diez Roux stated that the day’s goal was to broaden the conversation about the links between economic systems and health, given the understanding that the economy fundamentally affects health and health equity. The way that we as a society think about these links is often dependent on the narratives we have created about them, she continued, and these strong narratives perpetuate health disparities and are believed by many to be factual, natural, and unchangeable. Diez Roux noted that the first panel reviewed examples of current narratives about economic systems and health, and challenges and opportunities to change them. She expressed appreciation for the remarks by Zetzman, who spoke about the intentionality needed to resist the pervasive default narrative and more fully consider ways to reframe communication and the use of language. Diez Roux highlighted the importance of social movements in shifting narratives and of recognizing that change is a journey and that there might be unexpected opportunities along the way. She also reflected on the pandemic-era shift in language from “low-wage workers” to “essential workers,” illustrating the importance of framing information in an aspirational rather than a stigmatizing way, and underscored Smith’s statement that narrative change is about “making the radical the pragmatic.”

The second panel, Diez Roux said, focused on research, and she highlighted Simon’s comment that “the economy is what we make of it.” She reminded the audience of Grady’s examples of ways to shift and challenge dominant narratives, including talking about the people-driven economy and reframing the role of government, and how he described these actions as “cultural common sense.” Finally, Diez Roux summarized the third and fourth panels as focused on the role of narrative in social movements and policy change. Referring to the role of worker power and the push for wage increases from panel 3, she discussed how narrative shift was key in increasing wages of restaurant workers and creating the opportunity for change. Additionally, she recalled Blaine’s discussion of narrative change in city policy and developing an economy of human dignity, and Freeman’s comments about how storytelling can be used to advocate for policy change by amplifying authentic but often invisible voices. These discussions, Diez Roux said, illustrated how narrative change must be driven and led by those who are most affected by the problem. In closing, she emphasized that narrative change is a powerful tool that can be used in a variety of ways.

DISCLAIMER This Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief has been prepared by Alexandra Andrada and Stephanie Puwalski as a factual summary of what occurred at the meeting. The statements made are those of the rapporteurs or individual workshop participants and do not necessarily represent the views of all workshop participants; the planning committee; or the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

*The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s planning committees are solely responsible for organizing the workshop, identifying topics, and choosing speakers. The responsibility for the published Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief rests with the institution. This workshop was planned by Ana Diez Roux (Cochair), Drexel University School of Public Health; Mary Pittman (Cochair), Public Health Institute; Philip Alberti, Association of American Medical Colleges; Marc Gourevitch, New York University Grossman School of Medicine; Hilary Heishman, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; Sheri Johnson, University of Wisconsin; Tiffany Manuel, TheCaseMade, Inc.; Bobby Milstein, ReThink Health; Kosali Simon, Indiana University; and Monica Valdes Lupi, The Kresge Foundation.

REVIEWERS To ensure that it meets institutional standards for quality and objectivity, this Proceedings of a Workshop—in Brief was reviewed by Mary Pittman, Public Health Institute; Devin Thompson, National Community Reinvestment Coalition; Kimberly Brown, The Gates Foundation. Leslie Sim, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine served as the review coordinator.

SPONSORS This workshop was partially supported by Association of American Medical Colleges, Blue Shield of California Foundation, Fannie E. Rippel Foundation, Jefferson University College of Population Health, Kresge Foundation, Nemours, NYU Langone School of Medicine, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and The California Endowment.

STAFF Maggie Anderson, Research Assistant; Alexandra Andrada Silver, Program Officer; Alina Baciu, Roundtable Director; and Stephanie Puwalski, Research Associate.

For additional information regarding the workshop, visit https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/42960_06-2024_economic-systems-as-a-structural-driver-of-population-health-narrative-a-workshop.

Suggested citation: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2024. An introduction to economic systems as a structural driver of population health and exploring narratives and narrative change: Proceedings of a workshop—in brief. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/28032.

|

Health and Medicine Division Copyright 2024 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. |

|