The Gates Are Open: Operational Technology and Control System Security for Federal Facilities: Proceedings of a Federal Facilities Council Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 2 The Threat Environment and Current Agency Snapshot

2

The Threat Environment and Current Agency Snapshot

THREAT MITIGATION FOR OPERATIONAL TECHNOLOGY AND CONTROL SYSTEMS

Jon Huddleston, manager of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Defense Critical Infrastructure and Operational Technology program, said that he spent half of his 30-year career with the Army National Guard on active duty assessing and protecting critical infrastructure across the nation and the world. One thing he started to see more often were CS and OT installed as part of a project that were then left alone without a plan to conduct ongoing maintenance. As a result, he said, “we started to look at how do we have better awareness about operational technology and how do we better help our operation technology be resilient.” A challenge to doing so was that much of the information about operational threats was classified, making it difficult to provide information at the operator and contractor level for those without the proper security clearance. Over the past year, however, the “flood gates have opened,” said Huddleston, to allow for sharing more information about threats at the unclassified level, and he discussed several examples of adversarial targeting of OT and CS systems.

On May 24, 2023, the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) issued a joint cybersecurity advisory detailing activities related to the Volt Typhoon threat group, a state-sponsored actor based in the People’s Republic of China (CISA 2023). The advisory detailed the tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) that CISA and multiple U.S. and international security agencies had observed and the mitigations organizations could take to protect their critical infrastructure. Huddleston noted that this advisory did a good job of alerting the public and the owners of critical infrastructure about this threat.

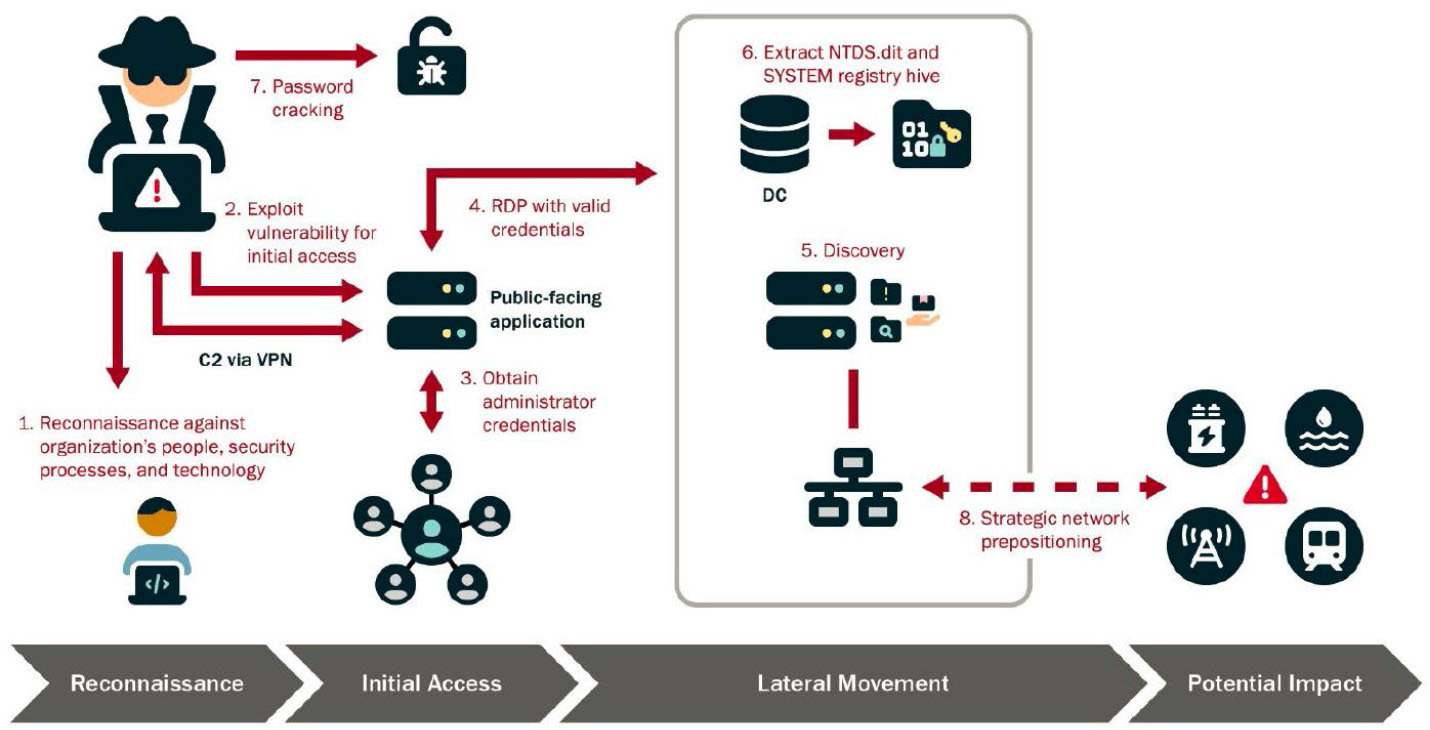

Huddleston said although Volt Typhoon actors have tailored their TTPs to the environment they want to get into, CISA and other agencies have observed a specific pattern of behavior across the identified intrusions. Volt Typhoon’s choice of targets and pattern of behavior is not consistent with traditional cyber espionage or intelligence-gathering operations, he explained, and the U.S. authoring agencies assess with high confidence that Volt Typhoon actors are pre-positioning themselves on IT networks to enable the disruption of OT functions across multiple critical infrastructure sectors. Volt Typhoon conducts extensive reconnaissance before attacking a system to learn about the target organization’s network architecture and operational protocols and then gains initial access to the IT network by exploiting known or zero-day vulnerabilities4 in public-facing network appliances. Volt Typhoon aims to obtain administrator credentials for the network, often by exploiting privilege escalation vulnerabilities in the operating system or network services (CISA 2024) (Figure 2-1).

___________________

4 A zero-day vulnerability is a vulnerability in a system or device that has been disclosed but is not yet patched. An exploit that attacks a zero-day vulnerability is called a zero-day exploit (Trend Micro undated).

NOTE: NTDS.dit, new technology director services director information tree; RDP, remote desktop protocol; VPN, virtual private network.

SOURCE: Jon Huddleston, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, presentation to the workshop on July 9, 2024.

Once Volt Typhoon gets into a system, they “live off the land,” which Huddleston explained, meaning that their activities do not look anomalous, making them difficult to detect. “This is one of the reasons why this alert was distributed so far and wide so that you can see and know what to look for in your networks,” he said. Volt Typhoon achieves full domain compromise by extracting the active directory database from the domain controller. It then uses offline password cracking techniques and elevated credentials for strategic network infiltration and additional discovery, where it focuses on gaining capabilities to move laterally into OT assets (CISA 2024).

The CISA alert, said Huddleston, provides a great deal of information about mitigations. These include hardening the attack surface; securing credentials, accounts, remote server access services, sensitive data, and cloud assets; implementing network segmentation; and being prepared and having a response plan when an issue is spotted. Securing cloud assets is particularly important, he said. “If you have anything in the cloud that could help them in their reconnaissance, [we] have to be careful about what we put in places that might be more accessible,” said Huddleston.

The second example Huddleston discussed was the May 11, 2023, cyberattack against Denmark’s power sector that exploited a firewall vulnerability (SektorCERT 2023). This exploit, which used two zero-day vulnerabilities and one recently released vulnerability, allowed an attacker to execute operating system commands remotely by sending crafted packets to affected devices. The initial attack compromised 11 companies, followed by a second wave of attacks 11 days later that over 4 days compromised another 11 companies. By the time the attacks were suppressed on May 30, 2023, Denmark’s power sector had been attacked some 200,000 times. In each instance, reconnaissance occurred, as with the Volt Typhoon attacks, that enabled the attackers to craft a tool to get through and control the firewall and the associated virtual private network (VPN). The attacks caused loss of power across Denmark.

Huddleston noted that the initial wave of attacks occurred 17 days after the initial announcement of a zero-day vulnerability. None of the 11 companies targeted in the initial wave had done anything to secure their systems and make them more resilient. He added that SektorCERT, CISA’s Danish equivalent, had published a threat assessment guide for OT that was specific to the country’s energy sector with 25 recommendations (EnergiCERT 2022). Of the 25, the following 10 were relevant to the energy sector attack:

- Only expose absolutely necessary services to the Internet;

- Update and patch all systems, including third-party software;

- Develop and maintain a contingency plan;

- Implement monitoring and logging, using EnergiCERT sensors, honeypots on the OT network, and extended internal monitoring, to enable detecting and responding to attacks promptly;

- Map all network entries to the production network;

- Segment the network into several layers so that at least OT is separated from IT, and consider further isolating or segmenting to contain or limit the potential damage from an incident;

- Identify and document all units in the production environment;

- Establish a vendor management policy that includes how to verify that vendors meet security requirements;

- Develop emergency procedures, including a plan for operating in island mode, for all business-critical processes so that the function can continue in the event of prolonged IT outages; and

- Conduct ongoing vulnerability scans and penetration tests to provide an overview of the attack surface facing the Internet.

FACILITY-RELATED CONTROL SYSTEM CYBERSECURITY OVERVIEW

Sandra Kline, director of mission assurance and facility-related CS at the Office of the Secretary of Defense, noted that in 2023, the Department of Defense (DoD) moved OT cybersecurity for the systems on its installations into the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Installations, Energy, and Environment after recognizing that simply delivering bricks and mortar without OT cybersecurity was no longer acceptable. Now, DoD is delivering IT and OT capabilities integrated with one another and with sensors and business analytics. Kline said that when she served as a military construction deputy director, she gained a much better appreciation of the large number of systems needed to live and work at a DoD installation and accomplish its mission, why they need to be cybersecure, and why they can be an attractive backdoor into getting to weapons platforms, industrial processes, or logistics systems.

Kline commended the U.S. Intelligence Community for identifying threats and getting that information to the public and Congress. That the Federal Bureau of Investigation and CISA are talking about these threats in public should give the general public pause, she said, because the publicly released information is just the tip of the iceberg. “If that is what we are talking about, what about all the things we are not talking about?” she asked. In fact, a recent updated national memo reiterated how often the United States has been invaded and attacked and how much malicious presence is already in the systems the nation owns and operates. “People have crossed the moat and are in our castle,” said Kline. “Now, what do we do? How do we respond in a different way while still having a really good moat and a really strong front door?” The threat, added Kline, is that facility-related vulnerabilities disrupt missions.

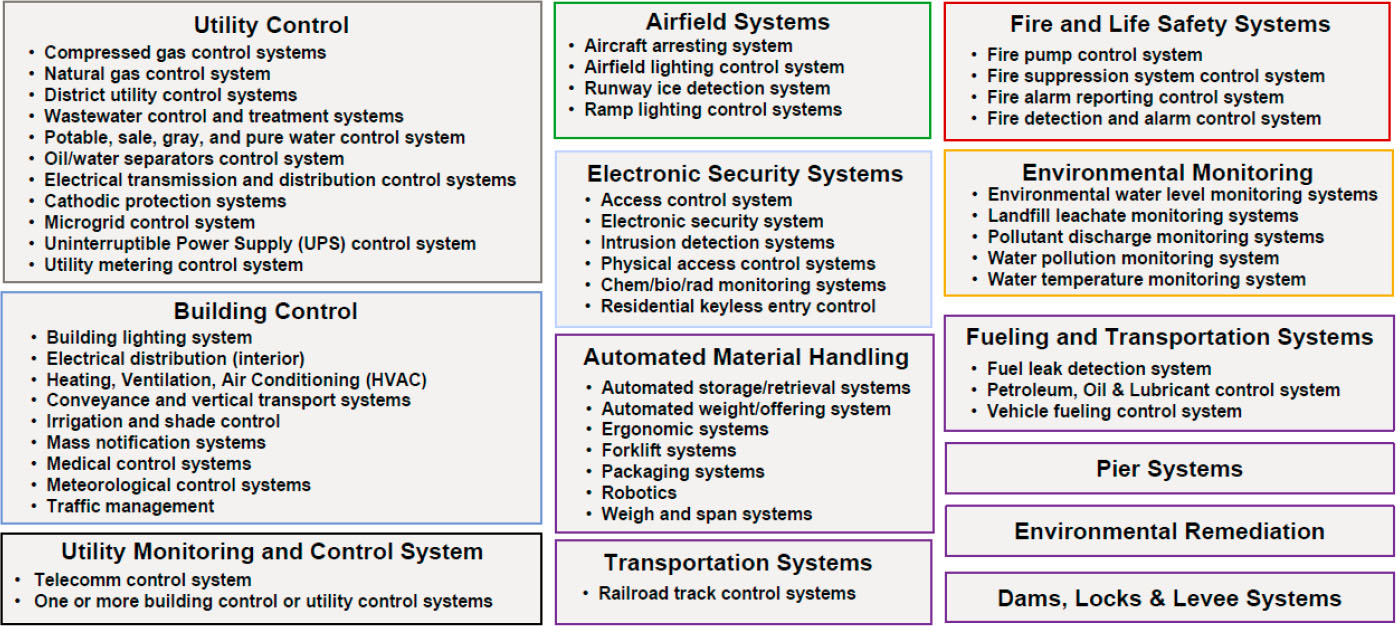

The important takeaway for her is that solving cybersecurity for OT in DoD will have to be a “team sport” because there is no single stakeholder. She and her colleagues have focused on the systems on military bases, campuses, and communities with OT. These include the facilities themselves, along with force protection, electricity, fuels, fire and intrusion detection, medical, water, and production and repair depots (Figure 2-2). The challenge is that within DoD, no one entity owns all these systems. For example,

SOURCE: Sandy Kline, Office of the Secretary of Defense (Energy, Installations, and Environment), presentation to the workshop on July 9, 2024.

her office is responsible for facility-related control systems other than medical systems and production and repair depots. While other parts of DoD control those two systems and weapons systems, there are connections and synergies of which to also be aware.

In 2017, Congress realized that DoD OT could be vulnerable to cyberattacks that would have physical consequences beyond compromised data. In response, Congress created two tasks for DoD and the Services in that year’s National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA). NDAA 1647 called for identifying vulnerabilities in weapons platforms and developing a plan to address those vulnerabilities, and NDAA 1650 directed DoD and the Services to identify vulnerabilities in the critical infrastructure supporting those weapon systems. This was groundbreaking work, said Kline, because this was not something DoD had done holistically.

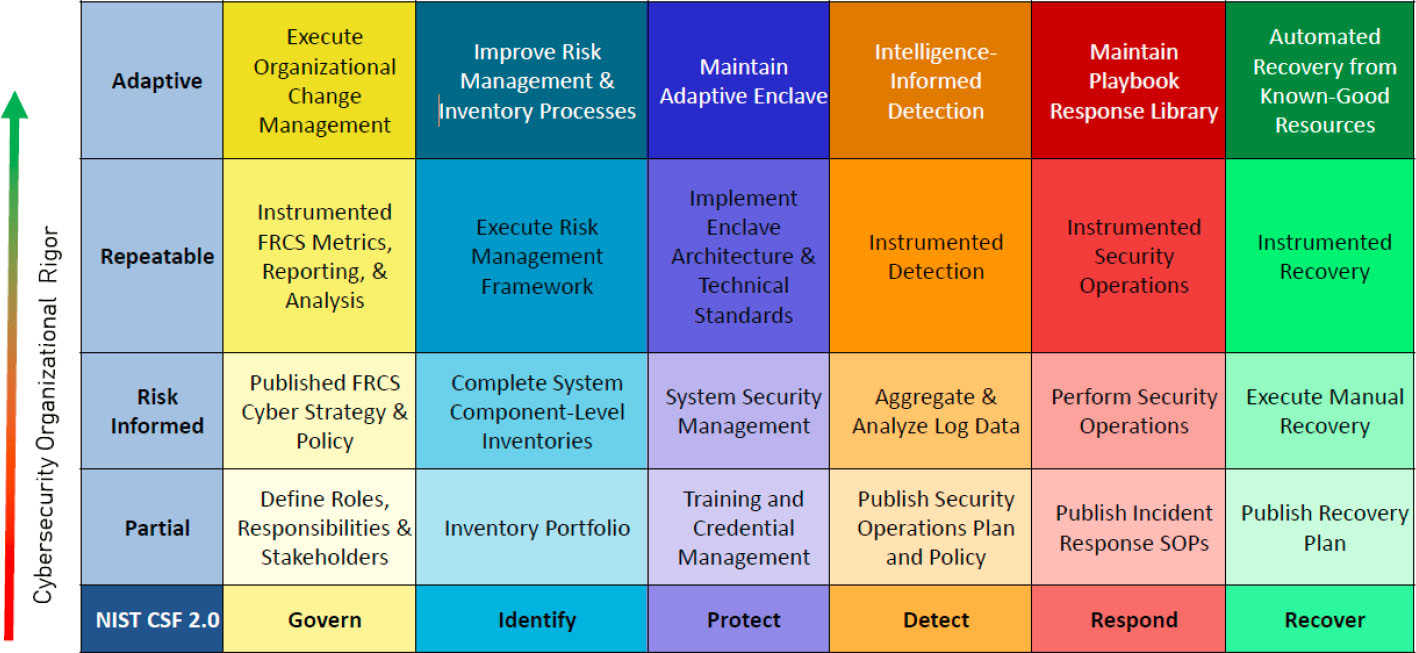

Kline said that when she would talk with the chief information officers for each of the Services and in industry, all she would hear about were the products they were going to buy and implement. This left her wondering how to create a vision and talk about the right architecture and processes. Her response was to use the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s (NIST’s) second version of its landmark cybersecurity framework to create a DoD-specific cybersecurity framework for facility-related CS (Figure 2-3). She uses this framework to talk to senior leaders in non-technical terms and help people be self-reflective and understand where they are regarding OT cybersecurity.

Some of what Kline and her colleagues are trying to do ends up addressing items on the right side of Figure 2-3. She noted that if someone is going to buy a piece of technology that works on the right-hand side, and they have not done all the rest of the tasks in the framework, there will likely be a problem with implementing a technology and sustaining it effectively. There are tools, she added, that can allow an owner or operator of facility-related CS, who understands where they are trying to go, to accomplish the tasks in the framework. “This is probably the most powerful tool I have in my toolbox because this is a way of level setting,” said Kline. “I can talk with industry about this. I can talk with the Services about this. I can talk with academia about this and say, let us understand where we are and where we need to be.”

NOTE: CSF, Cybersecurity Framework; FRCS, facility-related control system; NIST, National Institute of Standards and Technology; SOP, standard operating procedure.

SOURCE: Sandy Kline, Office of the Secretary of Defense (Energy, Installations, and Environment), presentation to the workshop on July 9, 2024.

Her office developed a CS resilience readiness exercise, the first of its kind “live fire” cyber resilience exercise that combines real-world cyber threat intelligence with actual physical effects, resulting in an unprecedented simulation of how a cyber event would cause tangible operational impact to mission-enabling, facility-related CS. This exercise, said Kline, is an evolution in cybersecurity simulation, education, and training for facility-related CS owners and operators that provides a hands-on experience of working through the physical disruption to an installation that results from a cyberattack. The exercise allows facility-related CS owners and operators to “train like they fight” by combining intelligence-driven threat injects with system outages, demonstrating the destructive potential of a cyberattack on CS, and crucially, what operators can and should do to mitigate damage and restore functionality.

Her office has been using this exercise to test the resilience of energy CS. The exercise involved having the local utility turn off the power for 4 to 12 hours and see what happens. It takes months for the installations to prepare, and DoD has partnered with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Lincoln Laboratory to understand their energy systems, how they operate with one another, and who has responsibility for backup generation. Her team has also been using this exercise to test cybersecurity, completing three tests this fiscal year, with a fourth scheduled for August 2024. In proprietary work that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has done with the MIT Lincoln Laboratory, they have been exploring the effect that different types of exploits will have once an attacker is on a network. This work, she said, shows on real systems with real missions what the potential effects of a successful attack can be, and it has been eye-opening to facility managers.

The plan going forward is to continue piloting these exercises for the next 2 years to demonstrate their capabilities. The idea is to use the lessons learned to inform military construction programs. One lesson learned when Fort Carson ran this exercise is that the different systems that vendors install are not integrated. As a result, operators are not getting a true vision of everything happening in the systems for which they are responsible. This raises the importance of getting the IT and OT communities to work

together to identify the cyber-commissioning requirements that can enable system integration in a meaningful way. The goal, said Kline, is for those installations that went through the NDAA 1650 process and know how their vulnerabilities can affect their mission to use these exercises to demonstrate that the actions they are taking and money they are spending will work as needed or if there are other steps they need to take.

Next steps, said Kline, include partnering with industry, which is leading the way in developing the technologies she needs. The DoD cybersecurity framework will serve as the foundation for that work and in implementing Executive Order 14028 on improving the nation’s cybersecurity by adopting the zero trust architecture (Rose et al. 2020). The framework is also the foundation for deploying DoD’s More Situational Awareness for Industrial Control Systems, a comprehensive, integrated, and automated cybersecurity solution for industrial CS; updating the military construction Unified Facilities Criteria (UFC) to improve cyber commissioning; and standardizing facility-related CS cybersecurity commissioning and retro-commissioning for legacy systems. “At the end of the day,” said Kline, “we are doing all this to ensure mission accomplishment and also to protect the health, life, and safety of the people that live and work on our bases.”

CYBERSECURITY AND HEALTH CARE ENGINEERING

Nathan Hizer, health care engineer at the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Office of Healthcare Engineering, said that one problem in health care today is that more systems are connecting to one another, which increases vulnerabilities. In the current threat environment, there are three important sets of capabilities. The first is visibility, or developing an inventory of the current systems present at a facility. One major challenge today is the move toward cloud-based systems and getting approval from the Federal Risk and Authorization Management Program (FedRAMP), which is expensive and time-consuming and something many small companies do not want to go through. As a federal agency, though, VHA requires all systems to be FedRAMP approved.

Hizer discussed “Section II: Internet of Things (IoT)” in the Office of Management and Budget’s (OMB’s) fiscal year 2024 guidance on federal information security and privacy management requirements (OMB 2023). In this section, NIST defines IoT devices as “those that have at least one transducer (sensor or actuator) for interacting directly with the physical world and at least one network interface (e.g., Ethernet, Wi-Fi, Bluetooth) for interfacing with the digital world.” Many IoT devices, said Hizer, constitute OT, defined by NIST as

Programmable systems or devices that interact with the physical environment (or manage devices that interact with the physical environment). These systems and devices detect or cause a direct change through the monitoring or control of devices, processes, and events. Examples include industrial CS, building management systems, fire control systems, and physical access control mechanisms. (Stouffer et al. 2023, p. i)

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), he noted, has a long list of items that fall under the IoT rubric (OMB 2023) (Table 2-1).

OMB, said Hizer, requires details about every IoT device, including asset identification, description, and categorization in terms of function, location, and type of system; who is responsible for managing and maintaining the asset; vendor information; software and firmware versions, including patches; network connectivity, integration, and application programming interface, including the Internet Protocol (IP) address and firewall rules; and security controls, including standards and protocols. The challenge, he said, is that the IoT inventory is constantly shifting, so keeping the inventory up to date is critical.

TABLE 2-1 Veterans Health Administration Systems Included as Internet of Things

| Building Automation Systems | Temperature Monitoring Systems |

|---|---|

|

Physical access control systems: Controls the electronic access systems, intrusion detection |

Camera monitoring systems |

|

Power monitoring/SCADA: Controls the electrical systems (utility, emergency generators, uninterruptable power monitoring, etc.) |

Energy management systems/utility metering: Controls monitoring various utility systems such as electrical, water, natural gas, steam and chilled water |

|

Fire alarm systems: Fire detection, alarm, and mass notification systems |

Lighting control systems: Controls interior and exterior lighting systems |

|

Vertical transportation systems: Elevators and escalators (video, texting, and 2-way voice communications) |

Emergency management systems: Mass notification to staff, patients, and visitors |

|

Laundry plant controls |

Onsite communication systems: Paging, 2-way radios |

|

Wander/elopement alarm systems: Patient wander alerting systems |

Nurse call-bed site patient communication equipment |

|

Medical gas alarm systems (air/oxygen/vacuum/nitrogen) |

Pneumatic tube systems: Transportation systems for various items around a facility |

|

Video boards: Messaging systems at front gate and in waiting rooms (Smart TVs) |

Water system (purification/reverse osmosis/steam/distilling/irrigation) |

|

Work order management systems |

Autonomous systems (laser guided vehicles, robotic vehicles) |

|

Smart vehicles (most vehicles) |

Police equipment (vehicle mounted cameras, body cameras, testing equipment) |

|

Fuel management and alarms |

Queuing systems (now serving) |

|

Testing devices (power monitoring/infrared cameras/borescopes) |

Radio frequency tracking systems |

|

Audio-visual systems |

Parking garage |

NOTE: SCADA, supervisory control and acquisition.

SOURCE: Data from Nathan Hizer, Veterans Health Administration, presentation to the workshop on July 9, 2024.

When onboarding systems, both software and equipment, the VA uses a technical reference model, enterprise risk analysis, and FedRAMP approval before deploying the new system. It also follows the Federal Information Security Modernization Act compliance requirements and Authority to Operate provisions and uses the VA’s governance, risk, and compliance tool provided by DoD’s Enterprise Mission Assurance Support Service (eMASS).

The second and third sets of capabilities address threat and anomaly detection, including root cause analysis and the subsequent response when something untoward happens. The Internet of Things Cybersecurity Improvement Act of 2020 (P.L. 116-207) required NIST to develop the Guide to Operational Technology (OT) Security (Stouffer et al. 2023) and IoT Device Cybersecurity Guidance for the Federal Government: Establishing IoT Device Cybersecurity Requirements (Fagen et al. 2021), and the Government Accountability Office (GAO) and OMB in particular, to report on federal agencies’ progress in implementing those guidelines. Hizer said the GAO audit of VA systems is in progress, and OMB’s call for data from the VA was due by September 30, 2024.

Hizer noted that detection and response follow much of the standard plan for the VA’s enterprise network, with the response involving the use of forensic tools and playbooks. However, it is important to understand that OT networks in the health care setting differ from enterprise networks, in that test environments are limited, the traffic is different, technology refresh rates are longer and more costly since most are custom-built systems, and they are built to last and operate in industrial environments. Many systems, in fact, are still running on Windows XP and Windows 7 and thus have limited and outdated security.

The VA, said Hizer, is studying whether it is better to stand up an OT-centric network operation center separate from its enterprise operation center, given these differences. “If you try to treat an OT and IT system the same, you may implode something on your OT system,” he said.

Going forward, the VA will enhance its OT/IoT enclave, its use of the eMASS tool, and its inventory management of OT devices using automation as much as possible as well as its ability to patch OT systems. It is also working to enhance its standard operating procedures (SOPs) for identical systems to streamline onboarding at each VA facility and enhance standard management of air-gapped systems. Finally, it is exploring additional ways to manage vulnerabilities when patches are not practical or available.

QUESTION AND ANSWER SESSION

An online participant asked the panel to discuss the tools available to assist with supply chain risk assessments of products before procurement and after implementation.5 Kline replied that the Department of Energy (DOE) recently published its Supply Chain Cybersecurity Principles (DOE 2024), and her team has contacted DOE to try to understand how those principles can apply to her office’s responsibilities. Military contracts, she said, address supply chain issues through contract language that emphasizes buying American. Huddleston noted that when federal entities complete risk management assessments for cyber supply chains, the resulting data are available to other federal entities, which informs blanket purchase agreement scripts. On the VA side, said Hizer, there is an Internet-facing technical reference model that vendors can view to see if their product is on the list. Vendors can request to be put on that list, although VA facilities do put products on that list without a vendor request. He noted that there is a website where VA facilities can go to see if there are already-approved products and added that FedRAMP is also a source of information.

Another question from an online participant asked if installing a domain controller provides a large enough benefit to employ in smaller industrial CS or if it is too much of a primary target. Huddleston replied that domain controllers, which were a target in the Danish power system attacks, are unnecessary for CS and OT, although they are an inherent part of larger systems, especially with geographically separate facilities. Hizer said that OT networks typically have a static IP address, which presents a challenge and requires correctly setting rules for firewalls and using isolated architectures following the Purdue model for industrial CS security (Garton 2019). A workshop participant commented that while employing domain controllers introduces a vulnerability, they can bring value to a system, too. For a large system with multiple workstations and head-in servers, domain controllers enable centralized logging for all network components and centralized credential management.

An unidentified workshop participant asked what the VA is doing to mitigate the most critical threats from an OT attack that could affect patient health or safety. Hizer said that is an ongoing, everyday challenge the VA addresses using localized, air-gapped systems behind locked doors. Challenges arise when trying to integrate them and have a central command center, and as devices become smarter. For example, the alarm panel for older medical gas systems found in hospital rooms uses mechanical open-close contacts, but newer models are digital and can connect over ethernet. “We have to develop ways to

___________________

5 The workshop’s second panel, covered in Chapter 3, addressed this question in more detail.

manage that,” said Hizer, which involves several teams in the OT and IT networks and requires going through the eMASS, governance, risk, and compliance processes. One thing the VA does is build redundancy into its systems so that it can take a controller offline and have the equipment still operate.

When asked if the VA has a process to ensure that when someone buys a new piece of equipment there are safeguards in place when that equipment is connected to the network, Hizer said the VA uses an enterprise risk analysis before deploying the equipment. He noted that it takes about 6 months for the team to onboard software for a new piece of medical equipment or OT. Once the internal and external connection process is approved, the network group sets up firewall rules and develops the security architecture before the new equipment can connect to a network. He acknowledged that onboarding anything at the VA is a long and challenging process designed to protect and manage its networks.

A workshop participant noted that every DoD facility is its own unique facility of privatized infrastructure with an operations staff that might be contractors or federal employees. The participant asked the panelists for their thoughts on how to approach this type of situation holistically at the local level to ensure that the system works. Kline replied that the Services have allowed there to be OT and equipment diversity at an extreme level, even at the same facility, which could be addressed by writing standardized SOPs for certain pieces of equipment. Hizer agreed with Kline and wondered why the VA has not standardized its building automation system. The reason, he continued, is that there is open bidding for equipment and no one vendor is the strongest in every location. A second workshop participant said that their building has more than 56 different kinds of air conditioners with no common communication standard. The problem, replied Hizer, is that equipment companies make their money off of service, not the equipment, so they deploy proprietary systems that only they can repair.

Kline asked if there would be value in federal agencies buying into existing industry standards, specifically International Society of Automation 62433, which defines requirements and processes for implementing and maintaining electronically secure industrial automation and control systems, and making it a requirement for all vendors to meet (BitChute n.d.). The problem there, replied a workshop participant, is that changing a standard would break the supply chain, given that there is significant industry lag time when adopting new standards for existing products.

Huddleston commented there is a constant battle between OT and cyber safety and cost. The cost analysts want to deploy fully automated systems that do not need manual controls in the OT system because that would save money. He has to reframe the argument in terms of safety and mission and what the cost would be if the automated system went down and there was no way to operate safely and on mission in a degraded environment. One workshop participant added that the cost of having humans monitor a system adds up over time to be far more than the cost of switching to an automated network, but the risk of not having a human involved is too high. Another participant said that the Army has had to take down an untold number of systems because they were not secure, which essentially is doing the attacker’s job for them. Perhaps DoD needs to conduct a real risk assessment to see if the risk of leaving something connected to the network is worth hiring multiple people to monitor that piece of equipment. The answer would depend on whether the system is controlling the air conditioning in a barracks or a hospital room, for example.

Kline commented that the installation facilities community writ large will always take a back seat to other investment scenarios. “We are going to have to be strategic in how we invest,” she said. “We also need to be more strategic in creating architectures that make sense.”

A workshop participant asked Huddleston if the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has a process for analyzing an attack, understanding it, and translating it quickly into engineering guidance that can inform projects that are under way. Huddleston replied that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ standards and criteria are more threat-informed now than ever. However, it has been difficult to get that information out beyond the security-cleared community because of the sources and methods used to gather that information. That situation is changing and getting to where CISA and North Atlantic Treaty Organization partners are sharing cyber-informed engineering standards and criteria.

The same participant countered that it could take 4 to 5 years to update a criterion in the UFC after a CISA advisory, to which another participant said that is not true, and that a small update can occur in months. The problem is not updating the document but identifying what the update needs to be—considering that the specifications used to build something today were dated 2 to 3 years earlier (when the contract was awarded) and what the contractor can legally be held responsible for building. The only solution is to require that every system has the latest patches and that every product with identified vulnerabilities has them mitigated before they are implemented.