K-12 STEM Education and Workforce Development in Rural Areas (2025)

Chapter: 3 Education Policy, Funding, and Programs in Rural Areas

3

Education Policy, Funding, and Programs in Rural Areas

The U.S. public education system has multiple interacting components that are influenced by policy and funding decisions at the federal, state, and local levels (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine [NASEM], 2022). Schools are typically divided into three levels—elementary (grades K–5 or sometimes preK–5), middle (grades 6–8), and high school (grades 9–12)—and three types: traditional public school, public charter school, or private school. A vast majority of students in rural areas are enrolled in traditional public schools. In 2019 approximately 9.8 million students were enrolled in rural public elementary and secondary schools—nearly one in five (19%) of all U.S. public school students (National Center for Education Statistics [NCES], 2023).

States have different variations or combinations of these school categories, and educational priorities are set by policies enacted by state education agencies and legislatures. These policies guide the development and implementation of academic standards, accountability measurements, and funding allocations. Most states also support “local control,” in which final decisions about instruction, scheduling, and academic programs are made by local education agencies.

Federal funding allocations for education also play a major role in how well educational priorities can be implemented in various communities. The policies and decisions made by multiple entities can influence whether students become interested in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) and pursue future STEM career opportunities.

In this chapter, we give an overview of the potential STEM learning opportunities for students both in and out of school and discuss policies and funding that can support or hinder students’ opportunities to learn in rural areas.

STEM LEARNING OPPORTUNITIES FOR RURAL STUDENTS

Similarities between rural, suburban, and urban schools include the general structure of school days for students and educators and the type of content that must be taught for compliance with state standards. There are also similar challenges in providing quality STEM learning opportunities to students in different types of school locations. In the elementary grades, instructional time for reading and mathematics are emphasized over time for science instruction, and instruction for science and engineering are underresourced and not highly prioritized (NASEM, 2022).

Beyond the similarities, rural students can encounter unique challenges for obtaining quality STEM education in terms of access to courses, quality instructors, and appropriate logistical needs (e.g., broadband access, transportation), any or all of which can impact their education and their decision or ability to pursue STEM-related interests, whether in their schooling or as a future career. The Center for Public Education (2023) identified five areas that may affect rural students’ access to quality learning opportunities:

- insufficient funding due to declining rural populations and economies in some areas,

- a digital divide that impedes students from accessing learning resources and developing digital literacy,

- local schools that lack the capacity to meet students’ needs,

- a worsening teacher shortage made even more apparent in rural schools by the COVID-19 pandemic, and

- a lack of research on policy and praxis issues relevant to rural education.

As more and more families leave rural areas, potential available funding for schools further declines, affecting school districts’ capacity to offer either the STEM programming and coursework offered in suburban and urban schools or qualified educators to provide instruction. The lack of qualified STEM teachers is particularly acute. Inadequate funding also contributes to the lack of technological access for students, whether by restricting the availability of quality broadband in classrooms and homes or preventing participation in digital learning opportunities (De Mars et al., 2022; Grimes et al., 2019; Kormos & Wisdom, 2021; Marksbury, 2017).

ACCESS TO STEM COURSES IN RURAL SCHOOLS

STEM pathways are in large part a function of students’ academic preparation and training throughout their K–12 schooling, particularly their access to and completion of high-quality and rigorous STEM coursework (Saw & Agger, 2021; Tyson et al., 2007). Students may choose or be guided to different STEM curricular paths through their performance and motivation in STEM subjects, and their choice or decision depends on the curriculum structures and resources of the schools they attend (Irizarry, 2021; Wang, 2013). Similarly, their college and workforce readiness in STEM can be significantly influenced by the course offerings and programming of their school or district. For example, STEM-focused schools, gifted and talented programs, and Career and Technical Education (CTE) programs at both the elementary and secondary education levels offer more intensive or advanced learning experiences and credentialing opportunities for STEM postsecondary education and careers (Gottfried et al., 2016; Saw, 2019; Steenbergen-Hu & Olszewski-Kubilius, 2017). Chapters 4 and 5 provide more information about STEM learning and pathways in rural areas.

Research has shown that inequities in access to advanced math and science courses begin well before high school, sometimes as early as kindergarten (Graham & Provost, 2012; Wolfe et al., 2023). Rural students have fewer opportunities to take STEM courses: 62 percent of rural schools offered at least one STEM course, compared to 88 percent of urban schools and 93 percent of suburban schools. Rural students also have less access to Advanced Placement (AP) STEM courses (Banilower et al., 2018; Crain & Webber, 2021; Mann et al., 2017; Saw & Agger, 2021; Showalter et al., 2017); data from 2015 showed that rural schools were much less likely to offer any AP STEM courses compared to schools in urban and suburban districts (Mann et al., 2017).

Dual enrollment programs allow students to earn postsecondary credit while still in high school and are available in about 90 percent of all rural high schools (NCES, 2020). In most cases, the relevant courses are offered online or at the postsecondary institution campus (Thomas et al., 2013). But rural districts face greater challenges than their counterparts in other locales, in providing transportation for students enrolled in such programs and finding qualified dual enrollment instructors (Zinth, 2014), who, in most states, need to meet requirements such as a master’s degree or the same qualifications as faculty in the partner postsecondary institution.

CTE programs are designed to help students develop technical, academic, and workforce skills that can be applied to employment and postsecondary education (Mobley et al., 2017; Stone, 2014; Stringfield & Stone, 2017). Rural students may attend CTE courses through area technical centers, which serve students from multiple institutions at the same time

(Advance CTE, 2017). These centers can provide diverse course offerings and make up for limited availability in a student’s home school district. While technical centers are not available in all states, they can build strong partnerships with business and industry partners, which could ultimately lead to more STEM-related courses and work in rural communities. Involvement in quality CTE pathways increases overall achievement, the probability of high school completion, college readiness, and employability skills (Lindsay et al., 2024).

Students who have access to and can complete advanced STEM courses are more likely to pursue STEM college degree programs and careers (Hu & Chan, 2024). But geographical disparities in STEM coursework offerings and completion favor nonrural over rural students, contributing to the underrepresentation of rural students in postsecondary STEM programs (Saw & Agger, 2021). One possible factor is that rural schools have, in general, smaller student populations than suburban and urban schools, and the smaller student population means a smaller teaching staff, which limits the number of courses the school can offer. And when rural schools do offer STEM courses, these are much more likely to be “alternative” or “applied” courses, which decrease access to advanced coursework (Wolfe et al., 2023).

STEM Teachers

As has been noted in this report, schools across the country are facing teacher shortages; these are most extreme in low-income areas, and some of the highest vacancy rates are in science and math (García & Weiss, 2019a, 2019b; Schmitt & deCourcy, 2022), which can negatively impact students’ STEM access and success (Rogers & Sun, 2019; Saw & Agger, 2021; Showalter et al., 2017). The shortage also appears to be worse in rural districts, especially for low-income rural areas (Ingersoll & Tran, 2023).

Using three decades of data from the Schools and Staffing Survey and its successor, the National Teacher and Principal Survey, Ingersoll and Tran (2023) show that vacancies are most prevalent in science and math: at the start of the 2015–2016 school year nearly 40 percent of rural public high schools had science vacancies and more than 35 percent had math vacancies. Many principals at rural schools with those vacancies reported serious difficulties filling them (Ingersoll & Tran, 2023). These STEM teacher shortages are exacerbated by inadequate rural school district funding that makes it more difficult to recruit and retain STEM teachers (De Mars et al., 2022). With fewer qualified STEM teachers, rural teachers may find themselves assuming responsibility for teaching multiple, diverse courses in the same semester or school year, (e.g., needing to prepare for and teach biology, chemistry, and physics at the high school level), increasing the need for preparation time (Goodpaster et al., 2012). Additionally, a study found

that rural science teachers had lower self-efficacy (i.e., confidence in their ability to teach science) compared to suburban science teachers (Saw & Agger, 2021).

In summary, the rural STEM teacher shortage impacts rural students’ ability to access STEM pathways through postsecondary education or workforce development opportunities. Chapter 5 discusses effective STEM pathways in rural areas and Chapter 6 presents a more in-depth look at educator recruitment, retention, and professional learning.

Transitioning to Postsecondary Education or the Workforce

Like their K–12 counterparts, rural postsecondary institutions play a significant financial and community role by providing pathways to careers that can help sustain rural communities. However, research has shown a disparity between rural postsecondary opportunities compared to urban. According to Wells et al. (2023), the rural-nonrural enrollment gap is affected by academic preparation, economic factors, and proximity, among others.

Rural students may feel underprepared for higher education, face challenges once in college, and experience hurdles that prevent them from completing their degree. Because many rural schools are small and have high proportions of low-income students they are less often able to provide a college-preparatory curriculum (Koricich et al., 2018).

The relationship between low socioeconomic status and rurality is important (Cain & Smith, 2020; Koricich et al., 2018), as poverty remains one of the strongest threats to rural students’ completing a postsecondary degree (Byun et al., 2012; Wells et al., 2019). For example, they may want to complete a degree without going into debt but not be aware of financial aid options (McNamee & Ganss, 2023). Based on High School Longitudinal Study data, the Postsecondary National Policy Institute (2024) observed that rural students took higher loan amounts ($7,005 vs. $6,354 nationally) and received lower grant amounts ($7,864 vs. $8,460 nationally).

Proximity to a postsecondary institution is a primary concern for rural students. Most students attend classes within 50 miles of their permanent home address (Hillman et al., 2021). But numerous rural areas face a significant shortage of educational opportunities because they are not near a postsecondary institution. In 2019 there were 516 rural colleges, compared to 2,439 nonrural. With the lack of educational options, rural students may leave the community to attend college and possibly seek employment away from the community, or they may skip postsecondary education and simply join the local workforce (Wells et al., 2023). This may explain why rural students have lower college enrollment and degree completion rates than urban or suburban students even though they have similar educational

aspirations (Koricich et al., 2020). Proximity also plays a role in the type of institution rural students attend. For instance, students attending a high school near a community colleges are less inclined to enroll in a four-year university (Hirschl & Smith, 2020). Two-year colleges predominantly enroll students living in areas with limited access to higher education facilities.

As with students in urban and suburban areas, community colleges can offer important STEM pathways for rural students. A 2023 Aspen Institute report (Barrett et al., 2023) reported 1.5 million rural students attending 444 rural community colleges. Postsecondary coursework at a community college can reduce financial and geographic obstacles to higher education for rural students. Graduates from rural community colleges play a crucial role in local economies. Research indicates that compared to their counterparts with a bachelor’s degree or higher, rural students who earn an associate’s degree often maintain stronger family connections and are more inclined to remain in their communities to seek employment opportunities (Muraskin & Lee, 2004). But rural students who seek to transfer to a four-year institution may encounter difficulties with credit transfer, inadequate academic support, limited financial aid, and differences in campus environment that may make them feel unwelcome (Byun et al., 2017). These difficulties often hinder their ability to successfully transfer or complete a four-year degree. Compared to their urban and suburban counterparts, rural students have the highest completion rates for certificates and associate’s degrees, but the lowest rates for bachelor’s degrees (NCES, 2023).

Broadband access is another barrier for rural postsecondary education (Rosenboom & Blagg, 2018). Without access to affordable high-speed internet, rural students are limited in their access to quality online postsecondary education options (Chen & Koricich, 2014).

Locational differences in financial resources also play a role. Postsecondary institutions in urban and suburban areas generate more revenue per student and have higher expenditures than rural institutions, limiting their ability to address the unique needs of rural students (Koricich et al., 2020).

Boynton and Hossain (2010) added a cultural component to the barriers facing rural STEM education by recognizing an idea in rural communities that students must move away to have a successful career. Research has shown that students who pursue studies in STEM fields often end up leaving their rural communities (Peterson et al., 2015). Byker (2014) suggests that to successfully implement quality STEM curriculum and learning experiences in rural communities, the first step should be to convince families and other community groups of the importance of STEM education. For example, offering tours of farms with chip-implanted cows, robotic milking machines, or high-tech barns can provide examples of work in rural areas

involving computational thinking, computer science, and data science. In other rural businesses, such as lumber mills and other forestry operations, orchards, and ski slopes, employees generate, collect, and analyze data using a combination of high-tech equipment and STEM proficiency. Many members of these rural workforces have certifications but not four-year STEM-related degrees, and other rural industries employ civil engineers, biologists, and workers with degrees in environmental science.

Out-of-School STEM Programs

Out-of-school educational environments can be classified as informal and nonformal, each offering enrichment activities to foster cognitive development. Informal learning experiences are voluntarily pursued outside traditional classroom settings (NRC, 2009) and usually self-determined by the learner, without a formal curriculum or formal evaluative processes. Examples of these experiences in rural areas include observing and understanding changing seasons for crops and hunting, learning agriculture from family members, or noting changing ecosystems on mountain hikes. Nonformal education occurs at a location other than a school (e.g., a zoo, museum, nature center) and is more likely to be aligned with formal curriculum. It may include clear learning goals but is usually not evaluated to determine the impact on learning (Eshach, 2007). Most out-of-school activities are usually classified as informal as a blanket term to include informal and nonformal learning environments.

Rural students and their families have fewer out-of-school and co-curricular STEM learning opportunities (Saw & Agger, 2021; Showalter et al., 2017). For example, Saw and Agger (2021, p. 600) report that rural communities are less likely “to hold math or science fairs, workshops, or competitions; inform students about math or science contests, websites, blogs, or other online programs; and sponsor a math or science after-school program.” However, an increasing number of STEM enrichment opportunities in online settings can provide students with valuable exposure to real-world learning experiences of STEM professions (such as virtual lab tours or field trips; Lakin et al., 2021) and potential careers (Culbertson et al., 2023; Nye et al., 2017). For example, the Nebraska Innovation Maker Co-Laboratory project developed a model to establish and support makerspaces in rural communities (Barker et al., 2018). The model supports collaboration between university faculty and staff and rural makerspaces by utilizing virtual reality and telepresence robots. The exploratory research project deployed telepresence robotics to teach, coteach, and provide project support to a rural community (population 7,000) makerspace. Virtual reality was used to teach creativity concepts, digital creation, and digital-to-physical manifestation of projects.

Research has consistently shown that middle and high school students who engage in STEM learning opportunities with in-person and/or online mentorship provided by near-peers or professionals in STEM fields tend to report higher levels of STEM workforce readiness and interest in pursuing a STEM college degree and career (Beauchamp et al., 2022; Finkel, 2017; Stoeger et al., 2013; Tenenbaum et al., 2017). Research is needed to understand how rural students can overcome disparities in out-of-school STEM experiences between rural and nonrural districts.

Informal Learning Opportunities

Rural communities lack large informal built environments for STEM, such as science centers, zoos, and botanical gardens, which are often found in urban ecosystems, but numerous local assets such as schools, libraries, museums, clubs, and supportive organizations like 4-H and Scouting America are available. Rural libraries and museums play a critical role in educating and supporting the learning of rural students.

About half of public libraries in the United States are in rural areas (Swan et al., 2013). They often provide access to public computers and the internet (Real & Rose, 2017), workforce development opportunities (e.g., assistance with applying for jobs), and afterschool STEM and other programs and events (Lopez et al., 2019; Real & Rose, 2017).

Approximately one in four museums are in rural communities, and they play a vital role in supporting learning and education related to history, culture, and science.1

Rural and some Indigenous communities are more likely to be near national parks and other large federal or state nature reserves (Byun et al., 2012). Students in these communities have almost immediate access to and can engage in real-life outdoor learning experiences not found in suburban and urban settings (Avery & Kassam, 2011). But the extent to which these resources are used for rural and Indigenous students as informal learning institutions has not been adequately studied, and may be worth examining as these places have the potential to serve as informal learning environments for place-based STEM education.

Research shows that youth and families need direct engagement with these multiple informal assets to explore and build STEM interest and skills (Allen et al., 2020). Families’ greater exposure to and engagement in STEM learning increase the likelihood that they will encourage and support their students’ interest and curiosity in STEM. Families and students in rural areas can also benefit from “collaborative partnerships between teachers and informal STEM practitioners that capitalize on the unique environmental

___________________

1 https://www.aam-us.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Museum-Facts-2024.pdf

offerings of rural areas in an authentic, hands-on way that makes learning come to life for young children within the context of their own backyards” (Hartman et al., 2017, p. 36).

POLICIES THAT SUPPORT OR LIMIT STEM LEARNING OPPORTUNITIES FOR RURAL STUDENTS

While all communities benefit from federal and state initiatives promoting high-quality STEM education and workforce development, rural communities have enjoyed disproportionately less attention and funding from both. One of the functions of government at all levels is to address such inequities. Historically, the foundational premise of the federal role in education has been to counter inequities in state and local education systems (Griffen, 2020; Hanushek,1989; Kaestle, 2016; Vinovskis, 2022). So efforts to improve STEM education and workforce development in rural communities require an understanding of the current state of federal and state support.

One of the most significant barriers faced by rural schools is inadequate funding. Considering that rural school systems serve populations with high poverty rates, a growing number of English learners, and hard-to-fill staff positions, the lack of funding is critical. The National Rural Education Association’s report Why Rural Matters 2023: Centering Equity and Opportunity (Showalter et al., 2023) found that the majority of states do not fund rural schools equitably: rural districts receive on average 17 percent of state education funding although they account for almost 30 percent of all districts. Other studies have found evidence that rural schools tend to have lower levels of per-pupil funding than nonrural schools (Irvin et al., 2012). And what it takes to reach equitable funding may be even more difficult than it seems, as inadequate economies of scale limit rural schools’ ability to provide cost-effective programming. In addition, the isolation of rural communities makes some resources and opportunities more expensive than in nonrural environments; for example, both the actual cost and opportunity cost of sending teachers away for professional development is higher in rural than in nonrural environments.

A 2014 case study surveyed K–12 teachers in rural Colorado about the challenges of providing STEM education and found that they were much more likely than teachers in nonrural schools to mention funding as a significant barrier (Henley & Roberts, 2016). The study also found that rural schools regularly forgo opportunities to apply for state or federal STEM grant funding because the administrative burdens associated with both applying for and winning these grants was too high. In fact, rural schools are often not even eligible for STEM grant funding as most formulas for state and federal grants use enrollment size as a primary qualifying factor,

and private foundations often require applicants to demonstrate scalability or impact as measured by the number of students served.

The next sections look at federal policies that contribute to the disparities described above, and then consider the local costs that challenge rural school districts, sometimes leading to school consolidation.

FEDERAL POLICY

Research shows that STEM-related activities and programs have been integrated in many K–12 curricula and course offerings but that there is a significant gap in the ability of rural schools to access these resources. Barriers to access are not a function of rural communities but of the current social and political landscape, which includes legislation that routinely ignores or discounts rural experiences and needs (Williams & Grooms, 2016). Most legislation concerning education policy and education funding mechanisms never mentions rural schools (Dahill-Brown & Jochim, 2018).

In the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Elementary and Secondary Education (OESE), the Office of Formula Grants manages the Rural Education Achievement Program (REAP), which is one of the few mechanisms that provides exclusive support for rural education funding. However, although REAP provides much-needed funds to rural districts, many rural schools may not benefit from the funds because of the administrative burdens of the program (Apling, 2007; Yettick et al., 2014). In addition, the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Postsecondary Education manages the Rural Postsecondary & Economic Development Program, which awards grants to institutions of higher education so they can develop career pathways aligned with local high-wage industry needs in order to increase the percentage of rural students who enroll, persist, and complete postsecondary education pathways.

Administrative burdens are often due to restrictions on the way funding is awarded, such as requiring some percentage of the award to be set aside for a specific purpose. Characteristics of rural school systems hamper their ability to comply with these requirements and in some cases make compliance cost prohibitive. Competitive grant opportunities, which require detailed applications followed by extensive review by the grant-making agency, could supplement state and local dollars but often include requirements that are impractical for rural schools (Brenner, 2016). For example, conditions of a professional development grant might make it too costly to implement the professional development compared to the amount of money allocated for it (Yettick et al., 2014). In addition, completing grant applications, which usually require a detailed description of the organization, problem to be solved, budget and justification for the budget, and other documentation, involves a substantial amount of work. Rural districts often

employ a small administrative staff, and few have the experience or time available to complete a lengthy grant application (Johnson et al., 2014).

In 2023 Congress approved $215 million to be split evenly between the two REAP subprograms: the Small Rural School Achievement (SRSA) program, which provides grants directly to local education agencies (LEAs), and the Rural Low-Income School (RLIS) program, which provides grants to states, which then award subgrants to LEAs. Although not a major source of funding for the operation of rural schools, these supplemental funds for both subprograms can be used to support activities described in the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), Title I-A (grants to LEAs for education of children from disadvantaged backgrounds), Title II-A (grants to support effective instruction), Title III (language instruction for English learners and immigrant students), or Title IV-A (student support and academic enrichment). In addition, SRSA funds can be used for Title IV-B (21st Century Community Learning Center) initiatives. Parent involvement activities can be supported only by RLIS. In addition, Title VIII of the Higher Education Act includes a clause in Part Q that was specifically written to create rural development grants. This program was authorized but has not received any funding in appropriations.

Most of the federal support for rural education originates in the U.S. Department of Agriculture, but rural schools are rarely aware of these funding opportunities (Rush-Marlowe, 2021). Research from the Brookings Institution found that federal assistance for rural communities is “outdated, fragmented, and confusing,” with over 400 programs housed in 10 different agencies and more than 50 offices or subagencies (Pipa & Geismar, 2022). Navigating how to apply for these programs, where they originate, and who might be eligible is often an insurmountable challenge for many rural communities. This lack of equitable, accessible funding for rural communities is a barrier to improvements in their STEM education.

Another challenge in rural schools’ access to federal funding is that most programs allocate funds based on population and community poverty. Since rural schools tend to be small and many of them experience depopulation, the amount of funding they receive is limited although their needs are greater than those in other locales.

Federal Programs

As the committee grappled with the funding inequities seen in many rural areas, it became evident that a thorough exploration of the number of federal programs supporting rural students, preK–12 STEM education, and workforce development was necessary. This section reviews federal programs across analytic groups: preK–12 education, STEM, rural, and workforce development. We start by reviewing the federal government as

a whole, then explore programs in the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF). Appendix B describes the methods used to identify programs and includes tables listing programs across federal agencies in the analytic groups. Overall, the committee found the following:

- Federal assistance is broad in scope, concentrated in cabinet-level agencies, and weighted toward project grants.

- There is an abundance of STEM-related programs across the federal government, though just three agencies administer over half of all STEM-related programs.

- Relatively few programs prioritize rural communities.

- Even fewer programs prioritize preK–12 STEM education in rural communities.

- A small percentage of NSF grants focus on rural communities, and an even smaller percentage on preK–12 STEM in those communities.

- Given the differences in how rural is coded across agencies, it is challenging to draw firm conclusions about the overall picture of federal investments in rural preK–12 STEM education and workforce development.

Federal agencies provide assistance predominantly through competitively awarded project grants rather than formula grants that might require an application but without applicants competing for those funds. The use of project grants implies that agencies likely have greater flexibility to target resources effectively by leveraging agency expertise, but rural districts often do not have the capacity to submit competitive grant applications.

The Federal Program Inventory (FPI) dataset catalogues 1,946 formula and project grant programs across all federal agencies. Of these, 87 percent (1,689) are project grant programs and 13 percent (257) are formula grant programs. Seven (of 44) agencies—the Departments of Agriculture, Education, Health and Human Services, Justice, Interior, and Transportation and the Environmental Protection Agency—account for almost 70 percent of the grant programs across all agencies.2 Health and Human Services accounts for over 21 percent of all programs, administering 334 project grant programs and 75 formula grant programs. Interior and Agriculture account for about 12 percent each (238 project grants and 10 formula grants, and 215 and 27, respectively). The distribution of grants across agencies by the four analytic categories of interest in this chapter implies both the importance of

___________________

2 Although many other federal agencies, including the Departments of Defense and Energy, support STEM education, those programs are primarily aimed at higher education and not at rural areas, so they are not described in this chapter. See Table B-5 in Appendix B for more information.

STEM across agencies and a narrower constituency for preK–12 education and workforce development. Cabinet-level agencies operate all but a few of the federal programs related to preK–12, STEM, rural communities, and workforce development. This is unsurprising as noncabinet-level agencies tend to be smaller and focused on highly specific policy issues.

In addition to the agencies mentioned above, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and NSF stand out. Both are organized into directorates, and their Federal Assistance Listings numbers are assigned at the directorate level rather than to individual programs in the directorates. This approach can make it appear that NASA and NSF fund very few programs. And in other ways the data do not accurately reflect the breadth and depth of the agencies’ work, as a single program may be counted in none, one, several, or all of the analytic categories.

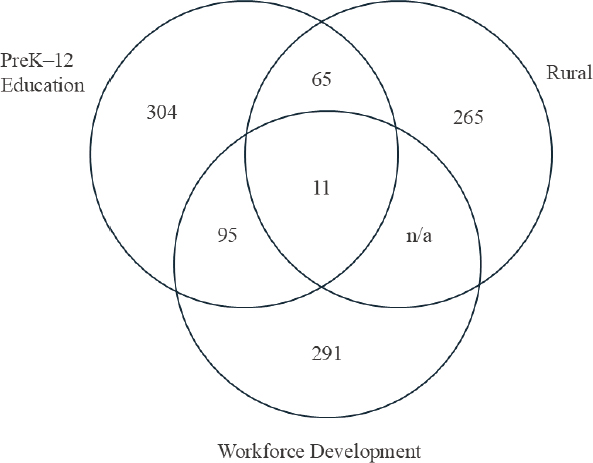

The next two sections detail the number of federal programs in the four analytic groups: preK–12 education, STEM education, workforce development, and rural. Based on the available data, the committee analyzed the intersectionality of both (a) STEM education programs and (b) workforce development programs with preK–12 education and programs targeted to rural communities.

STEM Education Programs That Intersect with PreK–12 Education and Rural Communities

Over half (58%) of all federal preK–12 education programs are administered by just three agencies: Education (90 programs, 29.6%), Health and Human Services (62 programs, 20.4%), and Agriculture (25 programs, 8.2%). The 339 preK–12 education programs constitute 15.6 percent of all federal programs. In contrast, almost 70 percent of all federal programs relate directly or indirectly to science, technology, engineering, or mathematics. Three agencies account for about half (52%) of the 1,355 STEM-related programs: Health and Human Services (351 programs, 25.9%), Interior (198 programs, 14.6%), and Agriculture (154 programs, 11.4%). While STEM abounds across federal programs, 13.6 percent (265 programs) of federal programs explicitly mention rural communities as a focus or beneficiary, and they are highly concentrated in a few agencies: Agriculture alone accounts for 34 percent (90 programs); Agriculture, Health and Human Services, and Interior combined account for 54.3 percent. Adding Transportation and the Environmental Protection Agency brings the total to 68.3 percent of rural programs in five cabinet departments.

Of the 170 programs (8.7% of all programs) that can be characterized as both preK–12 and STEM, almost two thirds (63.5%) are administered by the Departments of Health and Human Services, Education, Commerce, and Agriculture and the Environmental Protection Agency. Sixty-five programs

NOTE: n/a denotes lack of information on the number of STEM education programs targeted for rural communities.

SOURCE: Committee generated.

(3.3% of all programs) can be characterized as relevant to both preK–12 education and rural. These are relatively evenly distributed across 15 agencies. Within these 15, 46 percent are administered by Agriculture, Health and Human Services, State, Commerce, and the Environmental Protection Agency. Eleven agencies offer 39 programs—37 project grant and two formula grant programs—at the intersection of preK–12 education and STEM programs in rural communities. Figure 3-1 shows the distribution of federal investments across the analytic groups of preK–12 education, rural communities, and STEM education, and the intersectionality of the funds across these groups. The committee found programs at the intersection of preK–12 education and STEM education, preK–12 education and rural, and the intersection of all three analytic groups, but no information on the number of STEM education programs targeted for rural communities.

Workforce Development Programs That Intersect with PreK–12 Education and Rural Communities

The funding agencies and funding patterns of federal workforce development programs are similar to those of STEM education programs (Figure 3-2). Four agencies—Health and Human Services (107 programs,

NOTES: n/a denotes lack of information on the number of workforce development programs targeted for rural communities. The intersections between preK–12 education and workforce development do not also illustrate programs focused on STEM; the middle number shows the intersection of preK–12 education, workforce development, rural areas, and STEM.

SOURCE: Committee generated.

36.8%), Education (39 programs, 13.4%), Labor (26 programs, 8.9%), and Agriculture (19 programs, 6.5%)—administer two thirds (66%) of federal workforce development programs. Twenty agencies administer 95 programs at the intersection of preK–12 education and workforce development; Education and Health and Human Services administer about half (50.5%), and Labor and Defense administer another 14 percent. Fourteen agencies offer 62 programs—51 project grant and 11 formula grant programs—at the intersection of preK–12 education, STEM, and workforce development; here too, Health and Human Services offers half of these programs.

The purpose of this inventory is to identify federal efforts supporting preK–12 STEM education and workforce development in rural areas. The committee found 11 such programs, shown in Figure 3-2, and they illustrate the main conclusion of this report: that while the federal government invests broadly in terms of the sheer number of programs, very many of them are at best tangentially related to preK–12 education, STEM, rural communities, or workforce development. Many of those that are more directly connected

to these topics rely on grantees choosing to focus on them rather than the programs or agencies encouraging a specific focus on rural preK–12 STEM education (see, for example, the discussion below of Community Services Block Grants). NASA’s Office of STEM Engagement (a collection of programs)3 offers a different, strategic approach to supporting preK–12 STEM education and workforce development. Even this program, however, could be more strategically targeted to rural communities.

National Science Foundation Programs

As noted above, the NSF directorates rather than individual programs appear in the FPI data. To better capture the full inventory of federal programming focused on rural preK–12 STEM education and workforce development, the committee analyzed datasets provided by NSF, focusing on awards made in fiscal year (FY) 2024 (October 1, 2023, through September 30, 2024) with the word “rural” in either the title or the abstract. Importantly, the committee did not include awards made to an institution located in a rural area unless the title or abstract of the project included the word rural. Similarly, the committee did not consider work with Tribal Nations, Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders to be rural unless it was explicitly mentioned to be in a rural area. The committee acknowledges that this method may undercount work conducted in rural areas or focused on rural communities (e.g., work done on a reservation but not described as rural in the title or abstract), but chose to not risk overstating the investment in these communities. This tension highlights the difficulties of accurately counting grants using the existing databases, although NSF’s relatively new reference code for awards focused on rural America may help researchers examine this work in future fiscal years. The committee recognizes the possibility that grants on general topics in K–12 STEM or workforce development will have implications for rural settings, but those implications should not be assumed given the diversity both within rural areas and between rural and nonrural areas

Table 3-1 shows the number and amount of total awards and rural-related awards made across the nine directorates. The award amounts are only for FY 2024. In other words, some grants may have had only part of their funding awarded for FY 2024, so the dollar amount listed does not reflect the total amount awarded over multiple fiscal years. Although collaborative awards can be awarded to a single institution that provides subawards to collaborating institutions, the collaboratives listed in the table are for a single research project made in two or more separate awards to the collaborating institutions.

___________________

3 NASA’s Office of STEM Engagement is one example of the idiosyncratic and inconsistent way agencies provide data to SAM.gov and in turn to the FPI.

TABLE 3-1 NSF Awards and Amounts Awarded, FY 2024

| NSF Directorate | Total Number of Awards FY 2024 | Total Amount Awarded FY 2024 | Number of Rural Awards FY 2024 | Rural Amount Awarded FY 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Sciences (BIO) | 1021 | $584,958,427 | 24 | $18,932,492 |

| Computer and Information Science and Engineering (CISE) | 1815 | $778,966,305 | 37 (3 part of a collaborative) | $15,701,005 |

| Engineering (ENG) | 1645 | $653,427,494 | 39 (6 awards part of 3 different collaboratives) | $14,615,879 |

| Geosciences (GEO) | 1321 | $472,592,680 | 55 (28 part of 11 different collaboratives | $25,215,776 |

| Mathematical and Physical Sciences (MPS) | 2486 | $880,980,535 | 26 (2 part of a collaborative) | $8,037,672 |

| Office of the Director (O/D) | 331 | $275,668,598 | 43 (28 part of 5 collaboratives) | $37,116,313 |

| Social, Behavioral and Economic Sciences (SBE) | 769 | $192,072,645 | 18 (2 part of a collaborative) | $4,617,654 |

| STEM Education (EDU) | 1284 | $812,092,569 | 117 (30 part of 8 different collaboratives) | $78,409,468 |

| Technology, Innovation and Partnerships (TIP) | 1015 | $610,378,201 | 47 (10 part of 4 different collaboratives) | $117,672,611 |

| Total | 11687 | $5,261,137,454 | 406 (109 part of 34 different collaboratives) | $320,318,870 |

NOTE: Numbers for total grants for SBE and EDU provided by NSF. Numbers for total grants for the other directorates determined using the NSF public awards database (searching by directorate for grants awarded between October 1, 2023, and September 30, 2024). Award amounts reflect only the award amount for FY 2024, not the total amount awarded over multiple fiscal years.

SOURCE: Committee generated.

NSF’s Office of the Director had the highest percentage of its grants and funding awarded for work described as related to rural areas, but the fewest grants awarded overall in FY 2024. Most relevant to the committee’s work, of the 1,284 total grants awarded by the EDU directorate in FY 2024, 117 awards for 95 different projects (accounting for the number of collaborative grants) went to organizations that described their work as occurring in or related to rural areas. This is 9 percent of the total awards and 10 percent of the total amount awarded by EDU in that timeframe. Across directorates, over $300 million was awarded in FY 2024 for work described as related to rural areas, which is approximately 6 percent of the total award amount for that year, although the total number of awards for this work was 3.5 percent of the total number of NSF awards.

Further, although all of the rural-related grants are related to STEM, only a subset of those are related to preK–12 education and/or workforce development. Using the 406 awards with the word rural in the title or abstract, the committee reviewed the titles and abstracts of the awards to identify awards made to projects that included aspects related to learning experiences for youth in the preK–12 age range, including references to formal preK–12 schools or students; informal or out-of-school-time education activities (including citizen science and other youth learning) that were specified to be for preK–12 students; and/or teacher learning (which includes both preservice teacher education and inservice teacher professional learning). In addition, many of the awards were connected to STEM workforce development as it relates to postsecondary education in bachelor degree programs, but given the committee’s statement of task, only awards that described workforce development related to preK–12 education, including dual enrollment, certifications, transitions to associate degree programs, and STEM teacher education, were included in this analysis. In order to be coded for preK–12 education the abstract needed to provide a level of specificity about how the work would reach rural preK–12 students or educators in formal or informal settings. For example, abstracts describing “outreach” without more information were not included. Although it is possible that this coding undercounts educational experiences provided to rural preK–12 students either in or out of school time, the committee again chose to not risk overcounting the investment in these students. Coding was conducted by one person and checked by a second person; discrepancies were resolved through discussion. In an effort to count all of the awards that might relate to rural STEM preK–12 education and workforce development, the committee chose to be inclusive of all directorates as well as focusing more closely on all of the divisions within EDU. Table 3-2 shows the number of awards in each directorate coded as “rural” and included one or more of these aspects of preK–12 education among the rural awards.

TABLE 3-2 Learning for PreK–12 Aged Children in NSF Rural Awards

| NSF Directorate | Rural Youth Learning | Percent of Directorate Awards | Rural Youth Learning Award Amount | Percent of Directorate Awarded Amount |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Sciences (BIO) | 10 | 1.0 | $7,409,542.00 | 1.3 |

| Computer and Information Science and Engineering (CISE) | 9 | 0.5 | $4,942,349.00 | 0.6 |

| Engineering (ENG) | 18 | 1.1 | $7,621,740.00 | 1.2 |

| Geosciences (GEO) | 25 | 1.9 | $7,621,740.00 | 1.6 |

| Mathematical and Physical Sciences (MPS) | 12 | 0.5 | $3,775,881.00 | 0.4 |

| Office of the Director (OD) | 18 | 5.4 | $9,836,767.00 | 3.6 |

| Social, Behavioral and Economic Sciences (SBE) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| STEM Education (EDU) | 81 | 6.3 | $47,617,206.00 | 5.9 |

| Technology, Innovation and Partnerships (TIP) | 4 | 0.4 | $16,353,838.00 | 2.7 |

| Total | 177 | 1.5 | $112,328,874.00 | 2.1 |

NOTE: Numbers for total grants for SBE and EDU provided by NSF. Numbers for total grants for the other directorates determined using the NSF public awards database (searching by directorate for grants awarded between October 1, 2023, and September 30, 2024). Award amounts reflect only the award amount for FY 2024, not the total amount awarded over multiple fiscal years.

SOURCE: Committee generated.

Note that it is not possible to disaggregate the funds directed to rural youth STEM learning from the funding to support other activities of the grant, and many grants addressed learning experiences for youth in a variety of ways, including developing classroom modules or conducting summer camps. Of the 117 grants coded as rural and related to youth learning, many included activities for informal or out-of-school-time learning (including citizen science activities), either as the only educational experience or in conjunction with formal preK–12 education. In addition, several grants included activities for postsecondary education and workforce development and/or teacher learning. Table 3-3 shows the other foci of awards from all directorates except EDU, which is shown in Table 3-4. A single grant may be coded as more than one category, so the total across categories for each directorate might sum to more than the total number of grants awarded as shown in Table 3-2. In addition, because some awards focused on more than one of these, the award amounts are not shown.

TABLE 3-3 Relevant Foci for Rural Youth Learning Grants

| Directorate | Formal | Informal | Workforce | Teacher Learning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Sciences (BIO) | 7 | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| Computer and Information Science and Engineering (CISE) | 9 | 0 | 8 | 6 |

| Engineering (ENG) | 12 | 7 | 7 | 5 |

| Geosciences (GEO) | 21 | 5 | 11 | 1 |

| Mathematical and Physical Sciences (MPS) | 9 | 4 | 6 | 0 |

| Office of the Director (OD) | 13 | 13 | 13 | 8 |

| Technology, Innovation and Partnerships (TIP) | 4 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

SOURCE: Committee generated.

Given its mission, the EDU directorate included a wider variety of activities related to preK–12 STEM education than the other directorates (see Table 3-4). Many of the awards included aspects of educational research: one in DGE (focused on turnover in the STEM teacher workforce in high-needs areas such as rural communities) and 48 in DRL. Note that because some awards focused on more than one of these, the award amounts are not shown. Within DRL, one of the awards for informal learning also included an aspect for formal preK–12 education. Also note that the Division of Equity for Excellence in STEM did not make any FY 2024 awards that included an aspect of rural youth learning. A single grant may be coded as more than one category, so the total across categories for each division might sum to more than the total number of grants.

TABLE 3-4 Relevant Foci for EDU Rural Youth Learning Grants

| EDU Division | Formal | Informal | Workforce | Teacher Learning | Total Rural Youth Learning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graduate Education (DGE) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Research on Learning in Formal and Informal Settings (DRL) | 43 | 7 | 10 | 22 | 49 |

| Undergraduate Education (DUE) | 31 | 0 | 8 | 26 | 31 |

SOURCE: Committee generated.

In DRL, the Discovery Research PreK–12 (DRK-12) program funded 12 of the teacher learning awards, while Innovative Technology Experiences for Students and Teachers funded four, National STEM Teacher Corps funded five, and CSforAll funded one. In DUE, 22 teacher learning awards were through the Robert Noyce Scholarship program, 2 in Advanced Technological Education, and 1 each in IUSE and National STEM Teacher Corps. In FY 2024, DRK-12 made 80 awards and Noyce made 98; the percent of teacher learning awards with a rural focus in those programs is 15 percent for DRK-12 and 27 percent for Noyce. The committee did not conduct a quality analysis of the professional learning initiatives.

In addition to the categories previously mentioned, the committee’s coding of rural awards from NSF’s data revealed a small number of grants related to the portion of its charge concerning broadband and connectivity in rural areas. One doctoral dissertation improvement grant in the SBE Social and Economic Sciences division is examining the environmental and socioeconomic consequences low-earth-orbit satellites that could help provide broadband connectivity to remote areas. A collaborative CISE grant across three universities aims to improve broadband connectivity for schools, hospitals, and libraries that serve rural communities, and another CISE grant aims to improve internet connectivity and digital literacy in rural tribal communities. Finally, three different Small Business Innovation Research projects in the TIP directorate focus on connectivity through mobile broadband and other wireless communications that could serve remote areas.

Quality of Federal Programs

The number of federal programs provides some insight into the level of federal support for preK–12 STEM education and workforce development in rural communities. A more complete picture requires knowledge of the quality of the programs offered. But just as counting federal programs presents more challenges than one might expect, so too does assessing the quality of federal support. Federal programs are not interventions with standardized theories of change, logic models, inputs, activities, and resources. Rather, they are funding streams that support grantee projects that may (or may not) resemble more evaluable social interventions. This defining characteristic of federal programs makes it very difficult to conduct rigorous research consistent with National Research Council (2002) and NSF (2013) standards.

A recent report by the Committee on Equal Opportunities in Science and Engineering (NSF, 2024) describes features of successful strategies for rural STEM programs:

- access to experiential activities,

- financial support to increase access to a STEM degree,

- leveraging of technology to improve STEM pathways,

- bridging of formal and informal STEM education experiences,

- leveraging of investments in place-based research, and

- strengthened mentorship opportunities.

The programs listed below are examples of those at the intersection of preK–12 STEM education and workforce development in rural areas. For each program, the committee describes the primary objective, application priorities (for nonformula programs), range of grants (including overall funding), features of quality rural STEM programming, and kinds of performance data collected.

- Nita M. Lowey 21st Century Community Learning Centers

- Innovative Approaches to Literacy; Promise Neighborhoods; Full-Service Community Schools; and Congressionally Directed Spending for Elementary and Secondary Education Community Projects

- Rural Education Achievement Program

- Community Services Block Grant

- NASA Office of STEM Engagement

The committee presents these with the following observations. First, performance measures are generally simple measures of inputs and outputs that provide little insight into program improvement. In the case of the Community Services Block Grant, where somewhat more detailed data are collected, the collection imposes a substantial burden on grantees. Second, although several of these programs support preK–12 STEM education and workforce development in rural communities, they do so primarily or exclusively because grantees choose to do so, not because of a strategic prioritization of resources to support rural STEM learning. Finally, while the distributed choice model is the default for federal programs, NASA demonstrates that a more strategic prioritization can guide federal support for rural STEM, and NSF illustrates a blending of the two.

Nita M. Lowey 21st Century Community Learning Centers

The U.S. Department of Education’s Nita M. Lowey 21st Century Community Learning Centers (21CCLC) support academic enrichment in out-of-school, afterschool, and summer programming. This preK–12 formula grant program requires a focus on STEM insofar as improved mathematics achievement is a key outcome measure. It encourages grantees to offer additional STEM learning opportunities for students as well as workforce development, but these are at grantees’ discretion and not integral to the program’s operation.

Nothing in 21CCLC runs counter to the research features of quality rural STEM programs. Other than providing access to a STEM degree, the other features are well within the scope of the program’s intent.

The Government Performance and Results Act indicators for 21CCLC reduce a complex and varied program to student improvement on state reading/language arts and mathematics assessments, improvement in middle and high school student grades, improved student attendance, reduced in-school student suspension, and improved teacher-reported student engagement in learning. These indicators are preferable to counts of students participating in funded activities, but they shed little light on program performance and so are at best weak proxies for the features of quality rural STEM programming.

Promise Neighborhoods and Full-Service Community Schools

The Promise Neighborhoods (PN) program focuses on outcome improvement for children and youth in “the most distressed communities.”4 The Full-Service Community Schools (FSCS) program funds grantees to support “full-service community schools that improve the coordination, integration, accessibility, and effectiveness of services for children and families.”5 Like 21CCLC, PN and FSCS require a focus on STEM insofar as improved mathematics achievement is a key outcome measure and, although they consider additional STEM learning opportunities and workforce development, the integration of such activities is left to the discretion of grantees.

PN grants have a term of up to 24 months, and FSCS grants up to 60 months. Funding for PN in FY 2023 was $102 million and in FY 2024 $74 million; the president’s request for FY 2025 is $91 million. For FSCS, funding for fiscal years 2023 and 2024 was $76 million and $149 million, respectively; the president’s FY 2025 request is $200 million (OMB, 2024, p. 308).

PN and FSCS are both place-based, collective impact programs to support student and family success, school improvement, and community and workforce development. PN applications include three absolute priorities: nonrural and nontribal communities, rural communities (as defined by the NCES locale codes), and tribal communities. Competitive priorities include career and technical education programs. FSCS applications include an absolute priority for serving small and rural or rural and low-income schools as defined by the Small Rural School Achievement Program or the Rural and Low-Income School Program.

___________________

4 https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2024-06-27/pdf/2024-14054.pdf

5 https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2023-06-07/pdf/2023-12145.pdf

PN performance indicators include measures of student academic performance on state reading and language arts and mathematics assessments, student transitions from middle to high school, student absenteeism, postsecondary educational enrollment, postsecondary educational attainment, student nutrition, student safety, student mobility rates, family reading, family college and career discussions, and home broadband access.

The FSCS performance indicators include numbers of individuals served, student chronic absenteeism, student discipline, school climate, measures of implementation of key dimensions of full-service community schools, school staff qualifications and retention, graduation rates, and school spending.

Rural Education Achievement Program

Described earlier in this chapter, REAP is intended to help rural districts meet their particular needs and to “participate more fully and effectively in many of the ESEA programs and allow them to provide better educational services to their students” (U.S. Department of Education, 2021). LEAs can use SRSA and RLIS funds to support any allowable activities under ESEA Title I Part A, Title II Part A, Title III, and Title IV Parts A and B. These uses are consistent with both STEM education and workforce development, but nothing in REAP requires a focus on either.

Both programs are formula grant programs: SRSA provides assistance via formula to LEAs and RLIS by formula to state education agencies that in turn make subgrants to LEAs. Funding for REAP in both FY 2023 and FY 2024 was $215 million; the president’s request for FY 2025 is $218 million (OMB, 2024, p. 307). As with 21CCLC, PN, and FSCS, some REAP grantees use funds consistent with at least some of the Committee on Equal Opportunities in Science and Engineering features, but none of that activity is intentional; it is at best coincidental.

Performance reporting for REAP is by means of the Consolidated State Performance Report of the U.S. Department of Education OESE. This report provides a way for state education agencies to report performance across a number of U.S. Department of Education formula grant programs. As such, there are minimal data focused on REAP. The most salient data are brief narratives on outcomes per the state’s plan.

Community Services Block Grant

The Community Services Block Grant (CSBG) program is a cornerstone antipoverty program in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2022), and many grantees of this formula grant program support preK–12 STEM education and workforce development in rural communities. None

of these uses is required under CSBG, but all are allowed and implemented by grantees (known as Community Action Agencies). CSBG funds activities in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, and U.S. territories (American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the U.S. Virgin Islands), and conducted by federally recognized tribes and tribal organizations (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2022). Funding for CSBG was $771 million in FY 2023 and $770 million in FY 2024; the president’s request for FY 2025 is $770 million (OMB, 2024, p. 443).

The CSBG portfolio encompasses a greater range of services than 21CCLC, PN, or FSCS, but many projects share commonalities with projects funded by all three of those programs and likely (though perhaps to a lesser extent) with REAP projects. The balance of academic programming in CSBG, both generally and focused on STEM education, is unclear. The antipoverty focus of CSBG suggests that there may be a greater emphasis on workforce development and other postsecondary outcomes than the more school-focused 21CCLC and FSCS.

While the education programs discussed above require relatively few measures and they are generally distal to likely program effects, the CSBG annual report asks grantees and subgrantees for a wealth of data. The Community National Performance Indicators related to education and cognitive development provide somewhat more detailed information than similar indicators in the education programs. This additional detail should be of use to both government program officers and grantee and subgrantee project managers. Unfortunately, the estimated public reporting burden for each grant is 198 hours for grantees (i.e., states) and 697 hours for subgrantees (i.e., project staff).

NASA Office of STEM Engagement

NASA’s Office of STEM Engagement (OSTEM), like NSF’s directorates, is a collection of programs focused on promoting STEM engagement, learning, pathways, and workforce development. Of the five programs in OSTEM, Next Gen STEM supports a portfolio of work on preK–12 education. The projects include activities similar to those of 21CCLC, PN, and FSCS, but with an explicit focus on STEM engagement and/or workforce development. The OSTEM budget for FY 2023 was $154 million and for FY 2024 $144 million; the president’s request for FY 2025 is $144 million. Approximately $14 million was devoted to Next Gen STEM in FY 2023. While these numbers pale in comparison to the funding for 21CCLC, PN, and FSCS, OSTEM activities in rural areas could provide valuable examples for U.S. Department of Education programs and grantee projects. It should be noted that this funding does not explicitly focus on rural education; strategic planning could help move toward that focus.

Federal Interagency Working Groups

There are two relevant interagency working groups, but neither targets the intersection of preK–12 STEM education or workforce development and rural communities.

U.S. Department of Agriculture Rural Partners Network

Primarily led by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the White House, the Rural Partners Network (RPN) is a program meant to link rural communities to resources that promote infrastructure and economic development. Other participating agencies are the Departments of Commerce, Education, Energy, Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, Housing and Urban Development, Interior, Labor, Transportation, Treasury, and Veterans Affairs; the Environmental Protection Agency; the Appalachian Regional Commission; Consumer Financial Protection Bureau; Delta Regional Authority; Denali Commission; Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation; Northern Border Regional Commission; Small Business Administration; Social Security Administration; Southeast Crescent Regional Commission; and Southwest Border Regional Commission.

RPN provides a search engine that rural communities can use to find open grants across federal agencies based on need type (e.g., housing, job creation, transportation). As of September 2024, a search of grant programs related to STEM education yielded zero hits. And although workforce development programs abound, none are connected to K–12 students. The resource page for programs developed specifically for tribes, Native Americans, and Alaska Natives yielded one resource for K–12 education, the Indian Education Formula Grants from the U.S. Department of Education OESE (Rural.gov).

White House Office of Science Technology Policy Committee on STEM Education

In the Office of Science and Technology Policy, the National Science and Technology Council operates the Committee on STEM Education (CoSTEM), established in 2011 through the America COMPETES Reauthorization Act. CoSTEM has six interagency working groups (IWGs)—on Strategic Partnerships, Interdisciplinary STEM, Computational Literacy, Operational Transparency and Accountability, Inclusion in STEM, and Supporting Veterans in STEM Careers Act—that work together to carry out a Five-Year Federal STEM Education Strategic Plan, the most recent of which is for 2018–2023. The IWGs pursue three shared goals: foundational STEM literacy, broadening participation in STEM, and STEM workforce preparation. None of the IWGs have a rural-specific focus, although each goal can be taken up at the community level.

Implications for Federal Policy

The federal government funds an abundance of programs related to preK–12 STEM education and workforce development in rural areas. While numerous high-quality programs support preK–12 STEM education and workforce development, relatively fewer focus on rural STEM, and by and large they rely on the distributed choices of grantees to support high-quality STEM education and workforce development in rural communities.

Two possibilities emerge from the analyses conducted for this chapter. First, strategic prioritization could move programs like 21CCLC, PN, and FSCS toward consistent and widespread rural STEM education and workforce projects. Although some programs discuss STEM achievement, generally in the form of student performance on state mathematics assessments, the committee did not identify any that set either an absolute priority on rural STEM education or even a competitive or invitational priority for STEM education and workforce development in rural communities. This one change could have profound effects on the landscape of federal support for rural STEM education and workforce development. Second, the data are abundantly clear that there are almost countless opportunities to expand STEM projects to include education and/or workforce development. These opportunities range from U.S. Department of Interior conservation efforts in national parks to U.S. Department of Transportation engineering projects. In addition, knowledge building at NSF can play an important role in developing new approaches to address rural STEM education and workforce needs, and NASA’s OSTEM offers myriad examples of projects that can be adapted for rural communities.

SUPPORTING RURAL EDUCATION THROUGH STATE FUNDING AND POLICY

While federal funding provides some support to schools, it is only about 10 percent of total funding, leaving states and local districts to close the funding gap.6 Congress appropriates funds annually to 52 state education agencies (in the 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico), which in turn award subgrants to local education agencies and other public and private entities such as community-based organizations and educational service agencies. These subgrants are for terms of three to five years. Examples of the priorities that states may include in subgrant competitions include STEM programming and efforts to foster geographic diversity (U.S. Department of Education, 2023). State funding and policies have not traditionally attended to the unique needs of rural districts and schools, but some states have recently enacted legislation to

___________________

bolster funding for K–12 education in rural communities and to provide innovative exemptions for rural schools, enabling them to provide quality STEM education and workforce development pathways.

Addressing Rural School Funding Formula Limitations

Rural areas tend to “have poverty and lower budgetary revenues than their suburban counterparts” (Johnson & Zoellner, 2016, p. 3). Per-student expenditures are lower in rural school districts and rural schools compared to nonrural school districts and schools (Harris & Hodges, 2018; Showalter et al., 2023). For instance, nonrural school districts “spend an average of $7,685 on the teaching and learning of each student. This figure is over $500 more than the amount spent on the instruction of each rural student” (Showalter et al., 2023, p. 10). But average rural expenditures per student vary across the country, with New York rural districts spending $14,731 per student and Idaho ($4,908) and Mississippi ($5,484) spending the least (Showalter et al., 2023). Furthermore, since 2019, “the state-to-local funding proportions for rural districts have decreased in 27 states, creating more dependency on more inequitable local funding” (Showalter et al., 2023, p. 11).

Because rural school districts are more sparsely populated, they have higher costs related to student transportation (Johnson & Zoellner, 2016). This and other financial and budgetary contextual factors place more constraints on rural school district budgets to offer services and resources for students, such as support for multilingual learners and students with disabilities (Johnson & Zoellner, 2016). And these financial constraints often mean that rural teachers are paid less compared to teachers in nonrural school districts (Harris & Hodges, 2018).

States attempt to address these challenges by increasing the amount of funding that rural schools receive through funding formulas and policies that adjust funding for small school size and isolation. Some states provide extra funds to schools below a certain enrollment threshold; others use teacher-student ratios to make determinations about additional funding for some school districts. Although the state definition of an isolated or small school varies by state, small schools and districts are typically those with enrollment of fewer than 100 students. In many cases small schools are also isolated, but not necessarily all isolated schools are small (Evans et al., 2020).

States generally identify isolated schools based on one or more of the following criteria:

- large distance between schools,

- distance and time required for students to travel to their school,

- population density of the area surrounding the school,

- total geographical area of the school district, and

- whether geographic barriers are present.

Kolbe et al. (2021) report that at least 13 states adjusted their funding formula to account for their rural districts’ geographic location and population density. Others adjusted their funding formula for rural districts based on the driving distances needed to transport students, and 43 states provided supplemental funding for transportation. Some states have attempted to cut costs by encouraging or imposing district consolidation (Lavalley, 2018) and moving to a four-day school week (Anglum & Park, 2021), with mixed results.

To address the needs of small and isolated schools, states may adjust their funding formula to allocate additional funds on a sliding scale or, taking into account the size of the school or district, based on the budgetary discretion of the legislature. In some cases, states use more than one criterion to decide on the provision of additional funding but cap the funds on the school’s meeting a minimum threshold in the criteria. Gutierrez and Terrones (2023), summarizing information from different sources, find that 33 states provided additional support to small, sparse, or isolated districts and 10 states provided additional support based on distance (from 7 to 30 miles) to the nearest other district or school.

Some of the largest economic concerns for rural school districts relate to transportation and scarce opportunities for economies of scale. Transportation is important because rural districts generally cover larger geographic areas, and their schools are separated by long distances. Because of their low student population, it is also difficult for rural schools to implement economies of scale to support their needs. On average, for every dollar spent on transportation in rural districts, $10.36 is spent on instruction (most states spend between $9.64 and $12.74). The largest instruction-to-transportation spending ratio is in Alaska ($15.71 on instruction for every dollar on transportation) and the smallest is in West Virginia, which spends $7.46 on instruction for every dollar spent on transportation (Cornman et al., 2021). Rural Alaska districts tend to be small geographically and spend relatively little money on transportation compared to instructional costs, whereas West Virginia’s rural districts are consolidated to follow county lines, causing them to spend much more money in transportation relative to instruction.

Innovative State Policies

To provide more accessible STEM learning opportunities to rural students, some states are passing legislation and implementing new policies that directly benefit these students. For example, Texas recently passed

legislation to remove barriers and incentivize rural districts to create partnerships known as Districts of Innovation.7 The legislation provides funding and certain exemptions for rural school districts to partner together, along with local institutions of higher education and industry, to offer students multiple pathways to earn college credit, an associate’s degree, and/or industry-based certifications and Level 1 and 2 certificates. The legislation is designed to encourage replication of the state’s Rural Schools Innovation Zone, which offers five career pathway–based “academies” through the partnership of three rural school districts with multiple institutions of higher education and industry partners (Pankovits, 2023). Four of the five entities—Ignite Technical Institute, Next Generation Medical Academy, STEM Discovery Zone, and the Grow Your Own educator pipeline initiative—support STEM education and workforce development.

Legislation in Oklahoma aimed at ensuring that all students, including those in rural communities, have access to AP courses went into effect in 2024.8 Access may be offered at a school or other sites in the district; a technology center in the district; a school or other sites in another district; or through an online learning program offered by the Statewide Charter School Board or one of its vendors. The new law removes barriers that may have prevented access to course offerings and establishes a new program through the Statewide Charter School Board to offer AP coursework online for use by all school districts in the state.

Oklahoma also modified graduation requirements to allow school districts to offer STEM block courses (combining science, technology, engineering, and/or mathematics competencies), and thus enable students to receive high school graduation credit for two subject areas in a single course, as long as the teacher(s) in the block courses have the necessary certifications to provide instruction related to the subject areas.9 STEM blocks can help rural schools overcome scheduling barriers that often arise because of the schools’ more limited staffing compared to their urban or suburban counterparts.

In addition to legislative efforts to promote quality STEM education and workforce development in states, several state education agencies took advantage of opportunities afforded by the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA; 2015) to improve their accountability systems and provide incentives to school districts to develop priorities that aligned with their state goals for college and career readiness, including in STEM areas.

___________________

7 https://tea.texas.gov/texas-schools/district-initiatives/districts-of-innovation

8 https://www.oscn.net/applications/oscn/deliverdocument.asp?id=487131&hits=175+

9 https://www.oscn.net/applications/oscn/deliverdocument.asp?id=438855&hits=10793+10792+10558+10557+6327+6326+6092+6091+1703+1702+1468+1467+

ESSA offered states more flexibility and authority over their state accountability systems than before, particularly through the indicators for school quality and student success (SQSS) measures, which have been defined as “non-academic measures that must meaningfully differentiate schools from one another and also be comparable across schools” (Kaput, 2018, p. 2). Thirty-six states chose to add SQSS measures incentivizing various aspects of college and career readiness (Kaput, 2018) in their school accountability systems. Several states, including Connecticut and Delaware, include postsecondary study as an SQSS, measuring the percentage of students in each school enrolled in a two- or four-year postsecondary institution anytime during the first year after high school (Erwin et al., 2021). Mississippi and Florida prioritized the passage of AP and International Baccalaureate exams in their new SQSS measures, while Texas, Alabama, and Rhode Island added SQSS measures determining the percentage of students who receive industry credentials (Erwin et al., 2021). Oklahoma, California, and Utah included measures for the number of students enrolled in CTE pathways, and Arkansas and Michigan were two of many states that included measures for dual enrollment in college coursework (Erwin et al., 2021).