Legal Impacts to Airports from State Legalization of Cannabis (2025)

Chapter: Legal Impacts to Airports from State Legalization of Cannabis

LEGAL IMPACTS TO AIRPORTS FROM STATE LEGALIZATION OF CANNABIS

Timothy M. Ravich, Tressler, LLP, Chicago, IL; Erin N. Bass, Eric P. Berlin, Joanne Caceres, and Amy Rubenstein, Dentons LLP, Chicago, IL, and Chris Fernando, Radial Vector Consulting, Raleigh, NC

I. INTRODUCTION

In 1996, California became the first state to legalize cannabis1 for medical use. Since then, 39 states and the District of Columbia have legalized cannabis for medical use, and 24 of those states and the District of Columbia legalized and regulate the commercial sale and the use of cannabis by those over 21 years old (adult-use).2 This report is intended to provide insight into the legal impacts to airports from these and ongoing efforts by certain states to legalize cannabis by identifying key issues and corresponding legal guidance, where available. The relevance of this state-centric topic lies in the fact that airports, while physically located within individual states, operate as instruments of commerce subject to federal jurisdiction as part of the national transportation system. This duality, requiring airports to navigate multiple layers of laws and regulations, is particularly significant in the context of cannabis, where some states have legalized the substance for certain uses while federal law continues to prohibit it.

Consider, for example, that on the federal level, under the Controlled Substances Act (“CSA”), cannabis remains an illegal Schedule I substance (i.e., no accepted medical use and high potential for abuse) alongside heroin, lysergic acid diethylamide (“LSD”), methaqualone and peyote.3 Nonetheless, the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018—referred to as the “2018 Farm Bill”—removed from the CSA’s definition of “marihuana” plants it categorized as “hemp,” i.e., cannabis plants and their extracts, derivatives, and isomers with no more than 0.3% delta-9 THC.4 Now, the U.S. government divides the cannabis sativa L. plant into two categories: (1) the legal “hemp” plant with less than 0.3% delta-9 THC by dry weight; and (2) the illegal “marihuana” plant with greater than 0.3% delta-9 THC by dry weight. This means that there is a patchwork of federal, state, and local laws related to both cannabis and hemp.

Altogether, the divide between legal hemp and illegal “marihuana” on both federal and state levels creates a host of potential issues that airports must navigate (e.g., whether a product contains a hemp or cannabis ingredient can affect whether it is legal to sell in an airport and whether it can legally cross state lines). As the legal status of cannabis evolves, airports must carefully navigate these overlapping laws to maintain compliance, manage risk, and address operational issues that arise from the federal-state divide.

II. CANNABIS AND ITS COMPLEX LEGAL STATUS

A. The Plant, Distinguishing “Cannabis” and “Hemp,” and the History of Prohibition

1. Cannabis Sativa L., Cannabinoids, Effect on the Body

The term “cannabis” refers broadly to the flowering plant cannabis sativa L., and to the plant’s extracts derived from the glands on flowers.5 Cannabis grows with varying amounts of cannabinoids, the name given to naturally occurring compounds found in cannabis, including delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (“delta-9-THC”), the main substance responsible for the “high” effect that cannabis produces when ingested,6 and the less

___________________

1 This report uses the term “cannabis” in place of “marijuana” (or as it is generally referred to in federal law: “marihuana”) except when it is quoting the Controlled Substances Act or where the term “marijuana” is used in the information or source cited. Under federal law, cannabis “means all parts of the plant Cannabis sativa L., whether growing or not; the seeds thereof; the resin extracted from any part of such plant; and every compound, manufacture, salt, derivative, mixture, or preparation of such plant, its seeds or resin.” 21 U.S.C. § 802(16)(A). See Part IV, later, for further detailed discussion.

2 “Adult-use” is a term of art that refers to recreational use or not explicitly medical use. See Leafly, “Adult-use” definition, https://www.leafly.com/learn/cannabis-glossary/adult-use (last visited Jan. 28, 2025). The term “recreational use” may be used interchangeably as context requires.

3 According to a letter dated August 29, 2023, the Department of Health and Human Services (“HHS”) has recommended to the Drug Enforcement Administration (“DEA”) that cannabis be reclassified as a Schedule III drug under the CSA. HHS based this recommendation on a Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”) review of cannabis’s classification pursuant to President Joe Biden’s executive order in October 2022. Whereas Schedule I substances are reserved for those substances with no accepted medical use, the abuse rate is the determinate factor in the scheduling of a substance in Schedules II-V. If the DEA chooses to reschedule cannabis to Schedule III or otherwise, it will likely initiate complex administrative rulemaking proceedings under the Administrative Procedure Act (“APA”). There is a chance, however, that the DEA would issue the rule without the notice and comment period, relying on its authority to reschedule directly to comply with international treaties. Accordingly, readers should be aware that rescheduling could take months or could be final within weeks.

4 Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018, Pub. L. No. 115-334 (the “2018 Farm Bill”).

5 See 21 U.S.C. § 802(16)(A) (defining “marihuana” and “marijuana”).

6 See Food & Drug Admin., FDA Regulation of Cannabis and Cannabis-Derived Products, Including Cannabidiol (CBD) (Feb. 6, 2024), https://www.fda.gov/news-events/public-health-focus/fda-regulation-cannabis-and-cannabis-derived-products-including-cannabidiol-cbd (last visited Jan. 28, 2025) (Questions & Answers, Question 1: “What are cannabis and marijuana?”); see also DRUG ENF’T ADMIN., NATIONAL DRUG THREAT ASSESSMENT OF 2024, at 39 fig. 20 (2024), https://www.

impairing cannabinoid, cannabidiol (“CBD”).7 Although both “marijuana” (as cannabis rich in delta-9-THC is commonly referred to) and “hemp” are cannabis sativa L. plants, they have been bred for different purposes and generally appear different, and—importantly to each subset’s legal status—have different delta-9-THC and CBD ratios.8 Aside from the well-known psychoactive effects, cannabis has therapeutic benefits, although much remains unknown.9

2. From the “Marihuana Tax Act” to the Controlled Substances Act

At the start of the 20th century in the United States, cannabis was an ordinary industrial and medical/consumer good. The government encouraged farmers to grow hemp—a subset of cannabis further defined later—to produce items like ropes and sails. Unlike hemp’s industrial uses, cannabis, often in the form of tinctures, was largely legal and readily available at most pharmacies for consumer use in the late 19th century.10 This began to change in 1937 when Congress passed the Marihuana Tax Act, which effectively criminalized cannabis by restricting possession to individuals who paid an excise tax for certain very limited medical and industrial uses authorized under U.S. law.11

The U.S. federal government imposed further restrictions in the latter half of the 20th century. Congress enacted the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970, commonly known as the CSA, and designated cannabis, referred to in the U.S. code as “marihuana,” an illegal Schedule I controlled substance. Under the CSA, Schedule I substances are considered to have a high potential for abuse and no currently accepted medical use in the United States.12 Current Schedule I substances include heroin, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (ecstasy), methaqualone, and peyote.13 A substance that is included in Schedule I may not be manufactured, distributed, or possessed except for very limited, pre-approved research purposes.14 The CSA also prohibits controlling property where such activities occur, advertising cannabis for sale (e.g., through print, internet, TV, radio), selling unauthorized cannabis paraphernalia, and conspiring or aiding and abetting to do any of the aforementioned.15

3. Cannabis Reform: 1990s to the Present

The legal status of cannabis slowly began to change in the 1990s. Beginning with California in 1996, states began to enact various cannabis reforms based on the plant’s therapeutic potential.16 Then, in 2004, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals held in Hemp Industries Association v. Drug Enforcement Administration that a plain reading of the “marihuana” definition in the CSA made clear that certain parts of the plant were not prohibited (e.g., stalks and other parts with low quantities of THC), paving the way for legal import of hemp from other countries.17 While federal reform was slow to follow, there have been several incremental changes over the last decade, and, perhaps more importantly, the U.S. government has effectively permitted ongoing state reforms (discussed further in Section II.C. later) by not enforcing the CSA against states or those companies that comply with state laws.

The executive branch’s stance on non-enforcement of CSA prohibitions has remained consistent over the past decade. In 2013, then U.S. Deputy Attorney General James Cole authored a memorandum (the “Cole Memo”) addressed to all U.S. district attorneys acknowledging that, notwithstanding the designation of cannabis as a controlled substance at the federal level, several states had enacted laws relating to cannabis for medical purposes.18 The Cole Memo outlined the Department of Justice’s (“DOJ”) priorities relating to the prosecution of cannabis offenses, which focused on, among other things, preventing (1) its access to minors, (2) cannabis-related violence, and (3)

___________________

dea.gov/sites/default/files/2024-05/5.23.2024%20NDTA-updated.pdf (last visited Jan. 28, 2025).

7 Web MD, CBD vs. THC: What’s the Difference? (Oct. 31, 2023), https://www.webmd.com/pain-management/cbd-thc-difference (last visited Feb. 25, 2025).

8 See, e.g., RENEE JOHNSON, CONG. RSCH. SERV., R44742, DEFINING HEMP: A FACT SHEET 1 (updated Mar. 22, 2019), https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R44742#:~:text=%2C%20%C2%A710113).,5940(b)(2)); MONT. DEP’T OF REVENUE, Hemp and Marijuana, https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20190322_R44742_1b0195c6aa7e2cad29256c85a8574347c1ee833d.pdf (last visited May 29, 2024).

9 Stephen D. Skaper & Vincenzo Di Marzo, Endocannabinoids in Nervous System Health and Disease: The Big Picture in a Nutshell, 367 PHIL. TRANSACTIONS ROYAL SOC’Y B 3193 (2012), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3481537/#:~:text=The%20endocannabinoid%20system%20(ECS)%20in,actions%20throughout%20the%20nervous%20system (last visited Jan. 28, 2025).

10 Marijuana Timeline, PBS FRONTLINE, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/dope/etc/cron.html#:~:text=In%20response%20the%20U.S.%20Department,harvested%20375%2C000%20acres%20of%20hemp (last visited May 29, 2024) [hereinafter Marijuana Timeline]; Mary Barna Bridgement & Daniel T. Abazia, Medicinal Cannabis: History, Pharmacology, and Implications for the Acute Care Setting, 42 PHARM. & THERAPEUTICS 180 (2017), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5312634/.

11 See Marihuana Tax Act of 1937, Pub. L. No. 75-238, 50 Stat. 551 (repealed 1970).

12 21 U.S.C. § 812.

13 See, e.g., DRUG ENF’T ADMIN., Drug Scheduling, https://www.dea.gov/drug-information/drug-scheduling (last visited May 30, 2024).

14 21 U.S.C. §§ 812, 841.

15 Id. §§ 843, 846, 856, 863.

16 See Marijuana Timeline, supra note 10.

17 357 F.3d 1012, 1018 (9th Cir. 2004) (finding that the CSA did not give the federal government authority to regulate naturally occurring THC not contained within or derived from marijuana).

18 Memorandum from James M. Cole, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Guidance Regarding Marijuana Enforcement (Aug. 29, 2013), https://www.justice.gov/iso/opa/resources/3052013829132756857467.pdf (last visited Jan. 28, 2025).

its distribution in interstate commerce.19 States where cannabis had been legalized were not characterized as a high priority.20

In 2018, then U.S. Attorney General Jefferson Sessions issued a new memorandum to all U.S. Attorneys (the “2018 Memo”), which rescinded the Cole Memo.21 In its place, however, Attorney General Sessions authorized federal prosecutors to exercise their prosecutorial discretion in deciding whether to prosecute state-legal adult-use cannabis activities.22 Industry assumptions that the 2018 Memo would signal a change to federal enforcement never materialized.

U.S. Attorneys have taken no legal action against entities engaging in state law-compliant activities, and U.S. Attorneys General and U.S. Attorneys working under them have continuously stated that the DOJ does not seek to prosecute cannabis companies complying with state law.23 As recently as April 26, 2022, Attorney General Merrick Garland reiterated that prosecuting the possession of cannabis is “not an efficient use” of federal resources, especially “given the ongoing opioid and methamphetamine epidemic[s]” facing the nation.24

Since December 2014, companies strictly complying with state medical cannabis laws have also been protected against enforcement through a provision (originally called the Rohrabacher-Farr Amendment, now known as the Joyce Amendment) renewed annually in congressional appropriations bills, which prevents federal prosecutors from using federal funds to impede the implementation of medical cannabis laws enacted at the state level.25 Courts have interpreted the provision to bar the DOJ from prosecuting any person or entity in strict compliance with state medical cannabis laws.26 Moreover, because the Joyce Amendment bars prosecuting state-compliant medical cannabis companies, courts have found that related charges against entities providing services or products to such companies may be barred as well.27

Meanwhile, the federal government has initiated its own reforms on cannabis and hemp, albeit at a much slower pace than at the state level. Starting with the industrial hemp pilot programs authorized by the Agricultural Act of 2014 (the “2014 Farm Bill”), the federal government legalized hemp.28 Following that, the 2018 Farm Bill amended the CSA to exclude “hemp” from the definition of “marihuana.”29

More recently, on October 6, 2022, President Joseph Biden issued a Presidential Proclamation that pardoned certain prior federal offenses for simple cannabis possession, encouraged state governors to do the same on the state level, where permissible, and directed the Secretary of Health and Human Services (“HHS”) and the U.S. Attorney General “to initiate the administrative process to review expeditiously how marijuana is scheduled under federal law.”30

In response, HHS issued a letter to the Drug Enforcement Administration (the “DEA”) on August 29, 2023, recommending that cannabis be reclassified as a Schedule III drug under the CSA.31 On May 21, 2024, the Attorney General issued a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, recommending that cannabis be rescheduled to Schedule III.32 A move to Schedule III, if finalized, acknowledges that cannabis has accepted medical use and is less dangerous than drugs in Schedules I and II.33 However, rescheduling to Schedule III would not make state cannabis programs federally legal because no state licensed entity is registered, as required by the CSA, with the DEA or likely to be registered by the DEA, absent some legislation allowing state-licensed operators to do so. Regardless, the full impact rescheduling may have on state legal cannabis programs remains unclear.

___________________

19 The Cole Memo’s articulated federal priorities included: (1) distribution to minors; (2) revenue to criminal enterprises, gangs, and cartels; (3) interstate shipments; (4) cover for other illegal activities; (5) violence and use of firearms; (6) drugged driving; (7) cannabis production on public land; and (8) possession or use on federal property. See id.

20 Id.

21 Memorandum from Jefferson B. Sessions, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Marijuana Enforcement (Jan. 4, 2018), https://www.justice.gov/opa/press-release/file/1022196/dl (last visited Jan. 28, 2025).

22 Id.

23 One marked exception is that U.S. Customs and Border Protection has in the past year seized state-legal cannabis in New Mexico when discovered at immigration security checkpoints. See Chris Roberts, Why Are US Officials Seizing Regulated Cannabis in New Mexico? MJBIZDAILY (Apr. 22, 2024), https://mjbizdaily.com/customs-border-patrol-seizing-regulated-cannabis-in-new-mexico/ (last visited Jan. 28, 2025).

24 See Slates Veazey, Attorney General Garland Reconfirms the DOJ’s Hands-Off Approach Toward Federal Marijuana Prosecution, JD Supra (May 3, 2022), https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/attorney-general-garland-reconfirms-the-9983989/.

25 Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023, Pub. L. No. 117-328, Title V, § 531, https://www.congress.gov/117/bills/hr2617/BILLS-117hr2617enr.pdf (last visited Jan. 28, 2025). (“None of the funds made available under this Act to the Department of Justice may be used, with respect to any of the [states with medical marijuana programs], to prevent any of them from implementing their own laws that authorize the use, distribution, possession, or cultivation of medical marijuana.”).

26 United States v. McIntosh, 833 F.3d 1163 (9th Cir. 2016).

27 See, e.g., United States v. Samp, No. 16-cr-20263, 2017 WL 1164453, at *2 (E.D. Mich. Mar. 29, 2017) (defendant prosecuted for possessing a firearm while unlawfully using a controlled substance was entitled to evidentiary hearing regarding strict compliance with state’s medical cannabis laws prior to further prosecution by DOJ).

28 Agricultural Act of 2014, Pub. L. No. 113-79, § 7606.

29 Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018, Pub. L. No. 115-334, § 12619 (codified, as amended, at 21 U.S.C. § 802(16), 7 U.S.C. § 1639o et seq.).

30 Proclamation No. 10467, 87 Fed. Reg. 61441 (Oct. 12, 2022); Presidential Statement on Marijuana Reform, 2022 DAILY COMP. PRES. DOC. 883 (Oct. 6, 2022), https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/DCPD-202200883/pdf/DCPD-202200883.pdf (last visited Jan. 28, 2025).

31 Letter from Rachel L. Levine, M.D., Assistant Sec’y for Health, Dep’t of Health & Hum. Servs., to Anne Milgram, Admin., Drug Enf ’t Admin. (Aug. 29, 2023).

32 Schedules of Controlled Substances: Rescheduling of Marijuana, 89 Fed. Reg. 44597 (proposed May 21, 2024) (to be codified at 21 C.F.R. § 1308).

33 See 21 U.S.C. § 812(b)(3) (describing Schedule III drugs).

B. Federal Law

1. Controlled Substances Act—Cannabis

Today, every current state medical or “adult-use” program facilitates activities that remain illegal under the CSA, and therefore, the federal government could theoretically arrest and charge every active cannabis operator in the United States. The U.S. Supreme Court has held that as long as the CSA prohibits cannabis, under the Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution, the United States may criminalize producing and using homegrown cannabis even where states approve its use for medical purposes.34 However, it is not accurate to state that the CSA preempts state law. Indeed, to date, no court in the United States has ruled that state cannabis laws are preempted by U.S. federal law. In 2008, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to review a case brought by San Diego County, California, that sought unsuccessfully to establish federal preemption over state medical cannabis laws. In that case, the Fourth District California Court of Appeals held: “Congress does not have the authority to compel the states to direct their law enforcement personnel to enforce federal laws.”35

One of the more immediate anticipated reforms is cannabis rescheduling from Schedule I to Schedule III, discussed in Section II.A previously. In addition to the potential rescheduling of cannabis to Schedule III, there are currently many proposed incremental reforms in Congress, and industry participants anticipate some form of federal legalization in the next decade. In September 2023, the Senate Banking Committee passed the Secure and Fair Enforcement Regulation Banking Act (“SAFER”) Banking Act, which would protect financial institutions and other parties accepting money derived from the state-legal cannabis industry by “creat[ing] protections for financial institutions that provide financial services to [state-legal cannabis companies] and service providers for such businesses,” and also explicitly protects insurers.

Additionally, members of U.S. Congress from both parties have introduced bills that would end the federal cannabis prohibition, including by de-scheduling cannabis and regulating it. In the 117th Congress, Sens. Cory Booker (D-NJ), Ron Wyden (D-OR), and Chuck Schumer (D-NY) filed the Cannabis Administration and Opportunity Act, a bill that would regulate cannabis and expunge prior cannabis convictions; and Rep. Nancy Mace (R-SC) filed the States Reform Act, which would repeal the federal prohibition of, and further regulate, cannabis at the federal level. While the timing of federal reform remains unknown, it is expected that federal policy on cannabis will continue becoming more, rather than less, permissive, and legislative efforts to legalize cannabis or cannabis banking at the national level are likely to continue in 2025.

2. Agriculture Improvement Act—Hemp

Until recently, hemp (defined by the U.S. government as cannabis sativa L. with a THC concentration of not more than 0.3% on a dry weight basis) and hemp’s extracts (except mature stalks, fiber produced from the stalks, oil or cake made from the seeds, and any other compound, manufacture, salt derivative, mixture, or preparation of such parts) were illegal Schedule I controlled substances, along with cannabis generally, under the CSA.36 The 2014 Farm Bill authorized states to establish industrial hemp research programs.37

In December 2018, the U.S. government again changed the legal status of hemp. The 2018 Farm Bill removed hemp and extracts of hemp, including CBD, from the CSA schedules.38 Accordingly, producing, selling, and/or possessing hemp or extracts of hemp, including CBD, no longer violates the CSA.

Following the 2018 Farm Bill, the DEA has played a limited role in the regulation of hemp, mainly to weigh in on the legal distinction of cannabinoids found in both cannabis and hemp.39 In a series of letters to third parties, DEA argues that naturally occurring cannabinoids are generally legal, whereas synthetic cannabinoids may continue to be controlled substances, with one notable exception: The DEA has recently clarified that delta-9-THCA (an acidified version of delta-9-THC that converts to delta-9-THC when heated), even if hemp derived, is considered delta-9-THC (subject to a conversion factor of 0.877) and thus is also illegal as above hemp’s 0.3% threshold.40

Despite the DEA’s position, the plain language in the 2018 Farm Bill supports the claim that all other cannabinoids are federally legal. For example, delta-8-THC—a psychoactive cannabinoid that has a delta-9-THC content of less than 0.3%—is arguably legal under federal law. This view is supported by a plain reading of the 2018 Farm Bill, an opinion from the federal Court of Appeals of the Ninth Circuit, and early DEA guidance.41 However, delta-8-THC’s federal legal status is unresolved. Recently, reports have surfaced stating that the DEA considers delta-8-THC that is chemically converted from CBD to be an illegal controlled substance and that the agency plans to formalize its position that such synthesized cannabinoids are still illegal controlled substances.42

___________________

34 Gonzales v. Raich (previously Ashcroft v. Raich), 545 U.S. 1 (2005).

35 County of San Diego v. San Diego NORML, 165 Cal. App. 4th 798 (2008) (holding that a state law conflicts with the CSA only where it is impossible to comply with both the state and federal law).

36 21 U.S.C. § 802(16) (2016).

37 Agricultural Act of 2014, Pub. L. No. 113-79, § 7606.

38 Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018, Pub. L. No. 115-334, § 12619 (codified as amended in 21 U.S.C. § 802(16), 7 U.S.C. § 1639o et seq.).

39 See Interim Final Rule, Implementation of the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018, 85 Fed. Reg. 51639, 51641 (Aug. 21, 2020).

40 See, e.g., Letter from T. Boos, Chief Drug & Chemical Eval. Sec., Drug Enf ’t Admin., to Shane Pennington, Porter Wright Morris & Arthur LLP (May 13, 2024), https://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/24688803/24-9472-porter-wright-thca-05032024-signed.pdf (last visited Jan. 28, 2025).

41 See AK Futures LLC v. Boyd St. Distro, LLC, 35 F.4th 682 (9th Cir. 2022) (finding that a plain reading of the 2018 Farm Bill supports that hemp-derived delta-8-THC is legal hemp); DEA Letter to Donna C. Yeatman (Alabama Board of Pharmacy) (Sept. 15, 2022) (emphasis added) (here).

42 See, e.g., Graham Abbott, Delta-8 THC Derived from CBD Is Illegal, According to DEA Email, GANJAPRENEUR (Aug. 16, 2023), https://www.ganjapreneur.com/dea-confirmed-to-believe-delta-8-thc-synthesized-

Aside from the definition of hemp, which expressly includes isomers, extracts, and derivatives of the cannabis sativa L. plant,43 and its reference to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, the 2018 Farm Bill is otherwise silent on the legality of hemp cannabinoid products. Absent clear prohibitions, hemp products of all kinds—including ingestible, inhalable, and topical products—have entered the market.44 Additionally, new intoxicating cannabinoids have been developed and commercialized throughout the country. As further described later, states have been left to fill the gap by developing detailed regulatory schemes regarding the legality of such hemp products, and appropriate labeling, packaging, manufacturing, and testing guidelines aimed at ensuring consumer safety.

3. Relation to Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act

The 2018 Farm Bill’s framework for hemp production and its removal from the CSA does not alter the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (“FDCA”) or the authority of the Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”) to regulate certain cannabis and hemp-derived products.45 FDA maintains that it is illegal to introduce food with added CBD or THC into interstate commerce or market them as dietary supplements.46 Furthermore, any product marketed with therapeutic claims must be approved as a drug.47 Hemp foods without CBD or THC are legal,48 and the FDA has not explicitly deemed cosmetics or topicals containing cannabinoids as illegal.

Despite the FDA’s position, CBD and other hemp-derived products have proliferated, and arguably, many such products are federally legal today, notwithstanding the FDA’s position. The FDA has pursued a policy of “enforcement discretion,” noting repeatedly that it is taking action only against companies that make egregious “over-the-line” claims, including that CBD can “cure cancer” and “prevent Alzheimer’s Disease,” and adding that FDA has limited resources to enforce against such products.49 Based on the FDA’s current position, the clearest way to mitigate risk where hemp products are involved is to follow state laws, as further discussed later.

C. Medical Use, Adult-Use, and Low-THC Cannabis

Thirty-nine states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, Guam, and Northern Mariana have legalized some form of cannabis use for certain medical purposes. Twenty-four of those states, the District of Columbia, Guam, and Northern Mariana have also legalized cannabis for adults for any purpose (i.e., “adult-use”). Eight additional states have legalized forms of low-potency cannabis for select medical conditions. Only three states continue to prohibit cannabis entirely, although one has decriminalized possession of small amounts, leaving only Idaho and Kansas with complete criminalization.50 Appendix A contains a detailed map showing the various state legal cannabis programs.

While each state has a unique regulatory system, the states can broadly be characterized along the following distinctions: (1) whether it is a low-THC, medical-only state or also permits adult-use of cannabis; (2) whether the medical program is limited to certain predetermined conditions (restrictive) or allows for any medical use recommended by a doctor; (3) whether the state awards unlimited licenses or permits all applicants meeting certain requirements to obtain licenses; and (4) whether the state permits any local control over license types and numbers.51

For example, California allows medical and adult-use, allows for any medical use with the recommendation of a doctor, and has no limits on the number of licenses it will issue; however, California also allows for local control of license and types, resulting in many parts of the state with cannabis prohibitions.52 In contrast, Iowa is a low-THC medical state, is limited to certain conditions, awards limited licenses (only two to date), and does not include local control provisions.53

___________________

from-cbd-is-federally-illegal/ (last visited Jan. 28, 2025); see also Nicole Potter, Delta-8 THC Derived from CBD Is Illegal, According to DEA Email, HIGH TIMES (May 18, 2023), https://hightimes.com/news/dea-states-new-rules-for-synthetic-cannabinoids/ (last visited Jan. 28, 2025).

43 7 U.S.C. § 1639o(1).

44 See BRIGHTFIELD GROUP, CBD: FDA IMPACT & THE PATH FORWARD, 2022 MID-YEAR US CBD REPORT (June 2022) (estimating the U.S. hemp-derived CBD market is expected to reach $5.0 billion in retail sales in 2022).

45 7 U.S.C. § 1639r(c). See generally FOOD & DRUG ADMIN., Warning Letters for Cannabis-Derived Products, July 29, 2024, https://www.fda.gov/news-events/public-health-focus/warning-letters-cannabis-derived-products (last visited Jan. 28, 2025).

46 Id.

47 Id.

48 See FOOD & DRUG ADMIN., Statement from FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D., on signing of the Agriculture Improvement Act and the agency’s regulation of products containing cannabis and cannabis-derived compounds (Dec. 20, 2018), https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/statement-fda-commissioner-scott-gottlieb-md-signing-agriculture-improvement-act-and-agencys (last visited Jan. 30, 2025).

49 See Review of the FY2020 Budget Request for the FDA: Hearing Before the Subcomm. On the Dep’t of Agric., Rural Dev. Food & Drug Admin, & Related Agencies, 116th Cong. (Mar. 28, 2019), https://www.congress.gov/event/116th-congress/senate-event/LC64856/text (last visited Feb. 25, 2025).

50 Cannabis Overview, NAT’L CONF. OF STATE LEGISLATURES (updated Apr. 9, 2024), https://www.ncsl.org/civil-and-criminal-justice/cannabis-overview/maptype/tile#undefined (last visited Jan. 30, 2025). Note that the National Conference of State Legislatures lists Iowa as having a CBD/low-THC program. Dentons, however, considers Iowa’s program a comprehensive medical cannabis program.

51 See generally National Cannabis Industry Association, State-by-State Policies, https://thecannabisindustry.org/ncia-news-resources/state-by-state-policies/ (last visited Feb. 25, 2025) (describing state regulatory frameworks).

52 See CAL. CODE REGS. tit. 4, div. 19; California Cannabis Laws, Cal. NORML, https://www.canorml.org/california-laws/california-cannabis-laws/ (updated June 2023).

53 See IOWA ADMIN. CODE r. 641-154.1(124E) et seq.; Summary of Iowa’s Medical Cannabidiol Program, Marijuana Policy Project, https://www.mpp.org/states/iowa/summary-iowas-medical-cannabidiol-program/ (last visited May 30, 2024).

D. Hemp, CBD, Delta-8, and Other Intoxicating Isomers

All 50 states have legalized possessing and cultivating hemp following the passage of the 2018 Farm Bill.54 Since then, there has been a proliferation of hemp-derived products, including products with varying amounts of delta-9-THC or other similar naturally occurring or synthetic cannabinoids that can create a “high” effect (referred here as “intoxicating cannabinoids”). Such products are justified as legal/compliant in two ways: (1) the original plant from which the cannabinoids are extracted meets the legal definition of hemp; and (2) the percent of delta-9-THC over the volume or weight of the entire final ingestible product remains less than the 0.3% delta-9-THC legal limit.

Many states have sought to further regulate hemp, CBD, and additional intoxicating cannabinoid products that have entered the markets. Litigation regarding hemp and CBD products has followed, with lawsuits generally characterized as either: (1) consumer protection styled lawsuits, which claim that certain hemp products are illegal, unsafe, misleading, or falsely labeled,55 or (2) challenges from industry participants to rules or regulations that attempt to further restrict of even prohibit hemp products in the state.56 Generally, courts have upheld the legality of hemp products (unless fraudulent or mislabeled) while also affirming state’s rights to impose additional restrictions on products manufactured or marketed in the state.57

State laws vary in many important ways, including: (1) legality of hemp products, different cannabinoids, and specific product formats, (2) registration requirements for manufacturers and retailers, (3) manufacturing and testing requirements for products, and (4) labeling and packaging requirements.58 Appendix B includes two state hemp maps indicating the legal status of delta-8-THC and delta-9-THC products by state.

Certain states (including Utah) require hemp product retailers to register or obtain a retailer license,59 and some states require all products to be registered, either separately or as part of the retailer registration (e.g., Alaska).60 Requirements for manufacturing, testing, labeling, and packaging products vary from state to state.

III. FEDERALISM: THE INTERSECTION OF STATE CANNABIS LAWS AND NATIONAL LAW

A bedrock principle of American government is that federal law generally prevails over state law pursuant to the Supremacy Clause of the U.S. Constitution.61 This constitutional law ensures unified national policies, and its importance is particularly evident in areas like aviation and national security, where the federal government’s authority is comprehensive and unambiguous. In such cases, state laws that conflict with federal mandates are overridden—preempted—to maintain national consistency and cohesion.62

In areas where the Constitution does not explicitly grant power to the federal government and allows room for both federal and state lawmakers to legislate, opportunity exists—opportunity for state and governments to work independently or collaboratively—or at times, conflict. The legalization of cannabis at the state level is one such example. Despite several states legalizing cannabis for medical and adult-use use, federal law continues to classify cannabis as an illegal controlled substance. This discrepancy theoretically complicates enforcement and regulation, especially in federally governed spaces such as airports.

A recent case, Fejes v. Federal Aviation Administration,63 illustrates this general point. In Alaska, where state law permits the legal use and distribution of marijuana, a pilot transported cannabis within state lines using his aircraft. Although his actions were compliant with state law, the FAA revoked his pilot license, citing federal regulations that prohibit the use of aircraft for transporting marijuana. The pilot argued that his activities were strictly intrastate and did not involve interstate commerce, but

___________________

54 Andriana Ruscitto, Idaho Becomes Final State in U.S. to Legalize Hemp, CANNABIS BUS. TIMES (Apr. 22, 2021), https://www.cannabisbusinesstimes.com/news/idaho-becomes-final-state-to-legalize-industrial-hemp/ (last visited Jan. 30, 2025).

55 See, e.g., Colorado attorney general says company sold highly potent THC products as hemp, HEMP TODAY, https://hemptoday.net/colorado-attorney-general-says-company-sold-highly-potent-thc-products-as-hemp/ (last visited Jan. 30, 2025).

56 See Legal Challenges to State Hemp Laws and Regulations, NAT’L AGRIC. L. CTR., https://nationalaglawcenter.org/legal-challenges-to-state-hemp-laws-and-regulations/ (last visited Jan. 30, 2025).

57 See id.

58 See Regulating Hemp and Cannabis-Based Products, NAT’L CONF. OF STATE LEGISLATURES, https://www.ncsl.org/agriculture-and-rural-development/regulating-hemp-and-cannabis-based-products (updated Apr. 30, 2022).

59 See, e.g., UTAH CODE ANN. § 4-41-103.3 (requiring industrial hemp retailers to obtain a retailer permit). Utah Agricultural Code § 4-41-103.3.

60 See, e.g., ALASKA ADMIN. CODE tit. 11, § 40.510 (requiring retailer registrants to include list of industrial hemp product types intended to be sold by the retailer).

61 U.S. CONST. art. VI, cl. 2. But see U.S. Const. amend. X (“The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”).

62 Courts generally recognize two types of preemption—express and implied. Express preemption exists when the language of a federal law communicated an explicit intent by Congress to preempt state law. Implied preemption consists of “conflict preemption” and “field preemption.” A state law is in conflict and so preempted by federal law when compliance with both the federal and state laws is a physical impossibility, or when the state law stands as an obstacle to the accomplishment and execution of the full purposes and objectives of Congress. Field preemption exists when a court determines that a federal regulatory scheme is so pervasive that Congress must have intended to leave no room for a state to supplement it. See generally Rowe v. N.H. Motor Transp. Ass’n, 552 U.S. 364 (2008) (federal law preempts Maine statutory law purporting to regulate the delivery of tobacco to customers within the state by motor carrier); U.S. Airways, Inc. v. O’Donnell, 627 F.3d 1318 (10th Cir. 2010) (finding that state law that purported to govern an airline’s alcoholic beverage service was impliedly preempted by federal law).

63 98 F.4th at 1158 (9th Cir. 2024).

the court ruled against him. The court explained that airspace is under federal jurisdiction, and even intrastate activities involving aircraft fell within federal regulatory authority. Though relating to airmen certification and not strictly related to airports, the Fejes case offers a contemporary example of the interaction between state and federal laws in areas where the federal government maintains significant oversight, such as aviation.

Indeed, Fejes encapsulates the federalist system, which divides power between the national government and the 50 state governments.64 In aviation, for example, the U.S. DOT imposes drug testing requirements for transportation workers nationwide, ensuring a uniform safety standard that preempts conflicting state laws. Similarly, the CSA classifies cannabis as a Schedule I substance, making it illegal federally. However, the CSA’s narrow preemption clause allows for some state autonomy, provided state laws do not create a direct and unavoidable conflict with federal statutes. For more than a decade, state cannabis regimes and federal law have coexisted without such a “positive conflict,” illustrating the flexibility within the federalist structure. Additionally, courts have recognized that the CSA does not automatically displace or preempt state laws associated with controlled substances.65 Indeed, the CSA’s preemption provision is expressly narrow, stating:

No provision of this subchapter shall be construed as indicating an intent on the part of the Congress to occupy the field in which the provision operates, including criminal penalties, to the exclusion of any State law on the same subject matter which would otherwise be within the authority of the State, unless there is a positive conflict between that provision of this subchapter and that State law so that the two cannot consistently stand together.66

This provision makes clear that Congress did not intend to occupy the entire regulatory field concerning controlled substances or wholly supplant state authority in that area. According to the CSA, preemption is strictly limited to only those situations where there is “positive conflict” between state law and the CSA such that “the two cannot consistently stand together.” The various state cannabis programs do not affirmatively force any company or individual to do anything that would violate the CSA. And, perhaps more convincingly, for more than a decade, state cannabis regimes and federal law have successfully co-existed. In other words, no “positive conflict” between the CSA and state law exists, and thus, the CSA should not be considered to preempt state cannabis regimes (whether medical or adult-use).

In this context, this section explores three areas where federal law and state law potentially collide in the context of state cannabis legalization: the Fourth Amendment of the Constitution, the U.S. Department of Transportation’s (DOT) drug and alcohol policies, and airport grant assurances.

A. Cannabis and the Constitution: Airport Fourth Amendment Searches

The Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution protects citizens from unreasonable searches and seizures by the government. This protection is especially relevant at airports, where administrative searches are conducted to ensure safety, typically by detecting threats like weapons or explosives, though also extending to searches of contraband. In fact, courts have scrutinized cannabis-related incidents at airports for decades,67 as seen in cases like United States v. Warnock,68 where an airport manager’s involvement in a cannabis smuggling operation led to arrests, and United States v. Chapman,69 where the court applied state law through the Assimilative Crimes Act when federal law did not specifically cover marijuana possession. Such cases illustrate that while airports are federally regulated spaces, state law can fill legal gaps under certain circumstances.

In this context, the expansion of state-level cannabis legalization over the past few decades has not materially impacted fundamental Fourth Amendment issues at airports. As detailed in Exhibit 1, while some uncertainty may exist about the permissibility of transporting cannabis, the use and possession of cannabis remains subject to the long-standing constitutional framework established by the Fourth Amendment. Stated otherwise, airport security searches, even when involving the discovery of cannabis, must still adhere to Fourth Amendment principles and protections.70

The application of the Fourth Amendment at airports remains an important area of legal consideration and the

___________________

64 The concept also attaches to the relationship between state and local governments. The right of a state to preempt and subordinate local law is sometimes referred to as Dillon’s Rule, named in connection with court decisions issued by Judge John F. Dillon of Iowa in 1868. NAT’L LEAGUE OF CITIES, Cities 101--Delegation of Power, https://www.nlc.org/resource/cities-101-delegation-of-power/. (last visited Jan. 30, 2025). It affirms a narrow interpretation of a local government’s authority, in which a local or municipal government (i.e., a “substate”) may engage in an activity only if it is specifically sanctioned by the state government. 1 J. DILLON, COMMENTARIES ON THE LAW OF MUNICIPAL CORPORATIONS § 237 (5th ed. 1911).

65 See, e.g., County of San Diego v. San Diego NORML, 165 Cal. App. 4th 798 (Cal. Ct. App. 2008) (upholding California cannabis law against preemption challenge); White Mountain Health Ctr., Inc. v. Maricopa County, 241 Ariz. 230, 247 (Ct. App. 2016) (upholding Arizona cannabis law against preemption challenge); cf. Gonzales v. Oregon, 546 U.S. 243, 270 (2006) (“[T]he structure and limitations of federalism … allow the States great latitude under their police powers to legislate as to the protection of the lives, limbs, health, comfort, and quiet of all persons.”).

66 21 U.S.C. § 903 (emphasis added).

67 More than 3,700 cases are identified as part of a Westlaw legal database search of the search “fourth amendment airport.” E.g., United States v. Martinez, 625 F. Supp. 384 (D. Del. 1985) (search and seizure of the aircraft and the marijuana comported with the requirements of the Fourth Amendment). See generally Jennifer L. Petrusis, Sky High? The Federal-State Marijuana Law Conflict and Airline Travelers, 24 AIR & SPACE L. (2021); Linda Sickman, Fourth Amendment—Limited Luggage Seizures Valid on Reasonable Suspicion, 741 J. CRIM. L. & CRIMINOLOGY 1225 (1983); Jeffrey A. Carter, Fourth Amendment—Airport Searches: Where Will the Court Land?, 71 J. CRIM. L. & CRIMINOLOGY 499 (1980); Airport Security Searches and the Fourth Amendment, 71 COLUM. L. REV. 1039 (1971).

68 595 F.2d 1121 (7th Cir. 1979).

69 321 F. Supp. 767 (E.D. Va. 1971).

70 United States v. $124,570 U.S. Currency, 873 F.2d 1240 (9th Cir. 1989).

fundamental principles governing searches at airports have not significantly shifted since the relatively recent phenomenon of state legalization of cannabis began.

Notwithstanding the above, anecdotal research indicates that airport authorities (as opposed to the TSA) are not outright prioritizing searching for cannabis, suggesting that their primary focus remains on security rather than enforcing federal drug laws. However, the existence of federal prohibitions means that any discovery of cannabis can potentially trigger law enforcement action, despite the lack of emphasis on such searches by airport stakeholders.

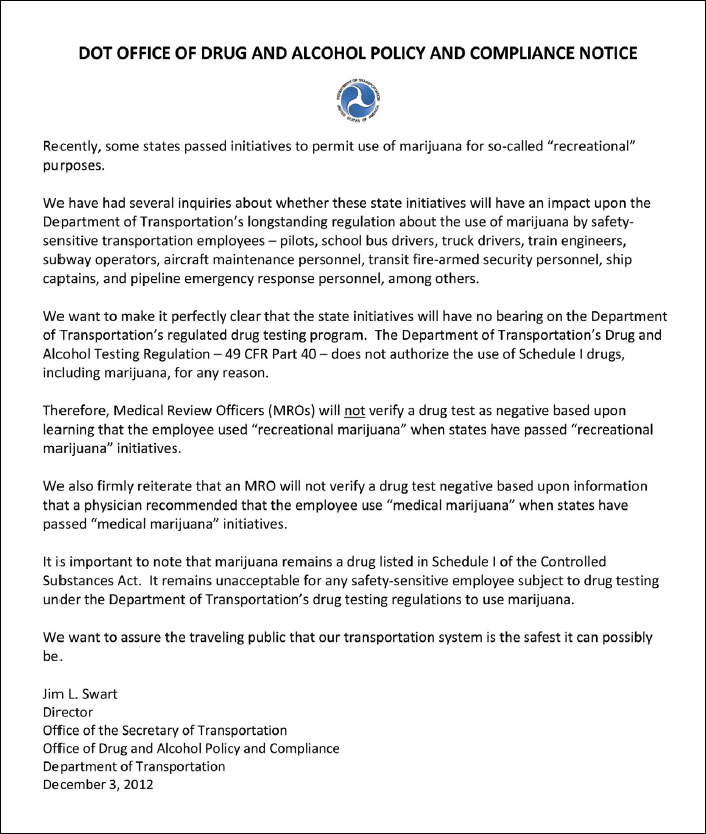

B. DOT Drug and Alcohol Guidance

For more than a decade, federal regulators have addressed airport issues related to the state legalization of cannabis. In December 2012, for example, the U.S. DOT Office of Drug and Alcohol Policy issued a “Compliance Notice.” That document explained that despite the legalization of adult-use and medical marijuana in some states, the DOT would continue to enforce strict drug testing regulations for safety-sensitive transportation employees. Specifically, the DOT’s Drug and Alcohol Testing Regulation (49 C.F.R. Part 40) maintained that marijuana, a Schedule I controlled substance, remained prohibited for employees in safety-sensitive positions, such as pilots, truck drivers, and train engineers, regardless of state laws. The Compliance Notice also emphasized that, “We want to make it perfectly clear that the state initiatives will have no bearing on the DOT’s regulated drug testing program.”71 Additionally, DOT stated:

- Medical Review Officers (“MROs”) will not verify a drug test as negative based upon learning that the employee used “recreational marijuana” when states have passed “recreational marijuana” initiatives.

- MROs will not verify a drug test as negative based upon information that a physician recommended that the employee use “medical marijuana” when states have passed “medical marijuana” initiatives.

- Marijuana remains a drug listed in Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act. It remains unacceptable for any safety-sensitive employee subject to drug testing under the DOT’s drug testing regulations to use marijuana (Exhibit 2).

C. Airport Grant Assurances

Whether (or to what degree, if any), state legalization of cannabis has on federally funded airports under the FAA’s grant assurance program is a concern for airports within the larger context of federalism detailed earlier. Grant assurances are commitments required from airport owners, sponsors, planning agencies, or other organizations that receive funds through FAA-administered airport financial assistance programs.72 By accepting these funds, recipients agree to adhere

___________________

71 United States Department of Transportation, DOT Drug and Alcohol Policy and Compliance Notice, https://www.transportation.gov/odapc/dot-adult-use-marijuana-notice (last visited Jan. 30, 2025).

72 See generally Federal Aviation Administration, Grant Assurance (Obligations), https://www.faa.gov/airports/aip/grant_assurances (last visited Jan. 30, 2025).

to certain obligations designed to ensure that their facilities are maintained and operated safely and efficiently, in line with specific conditions.73 Grant assurances sometimes are included with a grant application, incorporated into a final grant offer, or outlined in restrictive covenants attached to property deeds.74 The duration of these obligations varies based on factors such as the type of recipient, the useful life of the developed facility, and the specific conditions set forth in the assurances.

On October 19, 2019, the FAA issued guidance on the matter of cannabis cultivation at federally obligated airports, stating that the cultivation, storage, or distribution of marijuana is strictly prohibited on federally obligated airport property regardless of any state laws.75 The FAA received several inquiries about whether cannabidiol (“CBD”) oil and hemp products were considered controlled substances under the policy—a question that lingered for several years.76

On September 15, 2022, the FAA’s Director of Office of Airport Compliance and Management Analysis issued a memorandum—a compliance guidance letter (“CGL”)—to FAA Regional Directors, Airport District Office Managers, Compliance Specialists regarding “Compliance Guidance Letter 2022-02, Marijuana, Hemp and Cannabis Extracts Cultivation, Manufacturing, and Distribution at Federally Obligated Airports.” In consultation with the Office of the Chief Counsel, and for the purpose of ensuring “a consistent and nationwide position on the issue,” the FAA’s CGL specifically addressed the question whether CBD oil and hemp products were controlled substances in consideration of established federal governing federally obligated airports.77

The FAA’s 2022 CGL confirmed that marijuana is classified as drug code 7360 by the DEA and is a Schedule I controlled substance.78 Additionally, the CGL confirmed that a commercial marijuana distribution operation violates the Controlled Substances Act and constitutes a felony under federal law,

___________________

73 Id.

74 Id.

75 See Appendix D, hereto.

76 Id.

77 Id.

78 Id.

Title 21, United States Code, section 841(a)(l), which makes it “unlawful for any person knowingly or intentionally … to manufacture, distribute, or dispense, or possess with intent to manufacture, distribute, or dispense, a controlled substance.”

In this context, the FAA advised:

A federally obligated sponsor proposing to lease airport property for the advertisement, cultivation, commercial production, and/or distribution of marijuana presents substantial legal concerns under the aforementioned federal law …Consequently, a lease of airport property for these purposes would be unlawful, contrary to the public interest, and would subject the sponsor to potential criminal liability as a participant or facilitator of illegal activity. Further, if the FAA Airport District Office (“ADO”) suspects a violation of Federal law or regulation related to an AIP project (e.g. airport development supporting illegal activity), it is required to notify the DOT Office of Inspector General (“OIG”).

Accordingly, the FAA will not approve a change in land use or release of airport property (including interim or concurrent uses of airport land) for the advertisement, cultivation, storage, or distribution of marijuana (as defined by the CSA) at obligated airports.

The FAA’s CGL further addressed other cannabis plant products and extracts. With regard to CBD oil and hemp products, the FAA explained that it relies on guidance from the DEA on policies related to controlled substances on airports, noting that DEA itself had clarified that the New Drug Code (7350) was within the definition of marijuana: https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/schedules/marijuana/m_extract_7350.html.79

According to the DEA, any CBD oil and other products, made from parts of the cannabis plant outside the “marijuana” definition of the CSA (and Title 21 U.S.C. §§ 811 and 812) and with a less than 0.3% THC concentration, are not considered controlled substances.80

The FAA also recognized the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018—Farm Act—removed “industrial hemp” from the list of controlled substances outlined in the CSA.81 As with CBD oil, any hemp produced for commercial use must contain less than a 0.3% THC concentration, the FAA recognized, adding that, “[n] otably, hemp production and sales are still heavily regulated, and state, local, and Federal laws must be followed.” In this context, the FAA provided the following guidance:

Under these circumstances, and where Federal law allows, the FAA takes no position on the advertisement, cultivation, storage, sale, or distribution of legally allowable cannabis plant products and/or extracts on airport property. However, the FAA retains the authority to regulate airport land acquired with Federal funds or federally conveyed, including limiting the use of airport property to aeronautical purposes to ensure that airport facilities are available to meet existing and future aviation demand at the airport. Commercial or non-commercial use of airport property for or in support of legally-allowable cannabis extract products remain subject to all Federal statutes and FAA policies concerning airport rates, charges, revenue use, and land use. All Federal grant obligations still apply.

IV. EMPLOYMENT

A. The Joint Employment Doctrine: Vendors, Contractors, and Tenants

In general, within an airport, the airport operator itself directly employs some workers, while vendors, contractors, or tenant employees likely employ the vast majority of workers. For example, the airport managers, accountants, and marketing staff are likely directly employed by the airport operator. In contrast, the security agents working at airport security are likely employed by the Transportation Security Administration (“TSA”) (i.e., the federal government); the cashier at a fast-food restaurant is likely employed by the restaurant; and the baggage handlers in any given terminal are likely employed by an airline or third-party vendor. These examples of workers employed by entities other than the airport operator likely have no direct employment relationship with the airport operator; however, actions the airport operator takes with respect to its vendors, contractors, or tenants may impact those workers’ terms and conditions of employment. In turn, such actions impact degree to which any one of those workers could seek to hold the airport operator liable for employment law violations under the joint employment doctrine. Thus, airport operators need to be cognizant of the joint employment doctrine when setting cannabis policy for the airport.

Generally, under the joint employment doctrine, when two or more entities exercise control over a worker, codetermine essential employment terms and conditions, and impact other important employment factors, those entities may be deemed “joint employers” of the employee. If two entities are deemed joint employers, the secondary employer can be held legally responsible for the primary employer’s employment liabilities. An example helps illustrate the principle. Assume the primary employer is a fast-food restaurant within the airport. Also assume that a court found that the airport operator is a joint employer with the fast-food restaurant, and that the fast-food restaurant violated federal and state anti-discrimination statutes by terminating an employee on account of a protected characteristic (e.g., age, race, sex, disability, religion). In such a case, the court could hold the airport operator liable for the discrimination and jointly responsible for the financial damages owed to the employee. This risk is not merely theoretical; in at least one case, a court found an airport operator to be a joint employer with other entities, and many other cases where plaintiffs have alleged a joint employment relationship.82 Further, this is likely to be a common allegation in pre-litigation demand letters that are not publicly available.

The tests for whether two entities constitute joint employers differ based on the jurisdiction and the substantive law at issue.

___________________

79 Id.

80 Id.

81 Id.

82 See, e.g., City of Wichita v. Pub. Emp. Relations Bd. of Kan. Dep’t of Hum. Res., 913 P.2d 137, 141-42 (Kan. 1996).

Nevertheless, all joint employment tests look at the degree and nature of control that the secondary employer exercises over the workers. Thus, while an airport operator may have in interest in ensuring uniform applicability of its policies, including those related to cannabis, imposing such policies could be viewed by courts and regulators as form of control over the vendor, contractor, or tenant employees. As such, mandating such policies could subject the airport operator to liability as a joint employer. Cannabis-related policies to consider would be anything that would impact the vendor, contractor, or tenant employees’ terms and conditions of employment, whether directly or indirectly, such as hiring requirements, drug testing, documenting and reporting on drug testing, and what actions must be taken if a worker violates airport cannabis policy.

For example, assume an airport operator mandates that all workers within the airport be able to pass a full drug screen, including testing negative for cannabis. Assume this occurs in a state that offers protections for employees who use cannabis (as further discussed later). If a tenant refuses to hire an applicant because the applicant fails the drug screen for cannabis, the applicant could sue the airport operator (and the vendor), alleging that the refusal to hire violated state law and that the airport operator is liable as a joint employer. Unless the applicant is subject to a federal law that preempts state law, the airport operator could be found liable if it is found to be a joint employer.

B. Employment Considerations

This section addresses the interplay among federal, state, and local cannabis-related employment laws. It begins by revisiting the concept of federal preemption, which impacts the employment-law analysis. The section then gives an overview of federal and then state laws that impact how employers (including employers within an airport) can regulate cannabis in the employment context.

1. Preemption in the Context of Employment Law

The preemption doctrine, discussed in Section V earlier, plays a key role when considering cannabis impact on employment laws. Preemption arises in this context because many federal laws impose requirements that conflict with state employment laws about cannabis.

With respect to employment laws in an airport, a threshold question for assessing whether a conflicting federal or state law controls is whether the employee is subject to a specific federal law on the subject of cannabis. For example, federal government employees (e.g., TSA agents) likely must comply with federal law over a conflicting state law. As another example, if an employee is subject to specific DOT or FAA regulations (e.g., an air traffic controller), then the specific federal regulations will control over conflicting state laws, as discussed in more detail later. On the other hand, a fast-food restaurant tenant or a souvenir vendor employee would generally not be subject to specific federal laws governing their use of cannabis, and thus there would likely not be federal preemption over a conflicting state law.

The following sections supply some examples of federal laws that apply to employment matters in the airport.

a. U.S. DOT: Safety-Sensitive Roles

Aviation employees who work in “safety-sensitive” roles must pass drug testing mandated by the FAA.83 Such roles include employees performing the following duties (not all of which relate to airport operations):

- Flight crewmember duties.

- Flight attendant duties.

- Flight instruction duties.

- Aircraft dispatcher duties.

- Aircraft maintenance and preventive maintenance duties.

- Ground security coordinator duties.

- Aviation screening duties.

- Air traffic control duties.

- Operations control specialist duties.

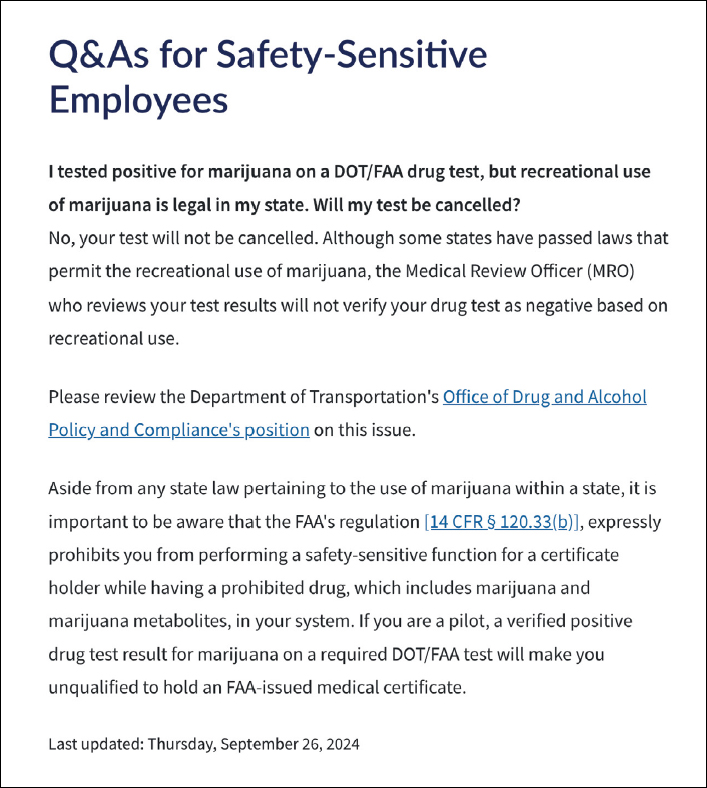

The FAA’s drug testing regulation requires the employee to test negative for THC-Marijuana, including during preemployment, post-accident, and reasonable cause testing.84 Similarly, the DOT’s Drug and Alcohol Testing regulations also require drug testing for safety-sensitive positions (Exhibit 3) and do not authorize the use of marijuana for any purpose.85

While some states have passed initiatives legalizing cannabis for medical or adult-use, and prohibiting employers from taking actions against employees who test positive for cannabis use (further discussed later), these state initiatives have no impact on the FAA’s or DOT’s longstanding regulated drug testing program. Under preemption rules, the federal regulations control over any employees subject to the regulations—i.e., employees performing what the regulations deem “safety-sensitive” functions.

Indeed, the DOT has spoken specifically on the preemption issue and also on its position with respect to CBD. On February 18, 2020, DOT published its “DOT Office of Drug and Alcohol Policy and Compliance Notice.” In the Notice, the DOT advised that, while it does not require testing for CBD, labeling of CBD products may not be accurate with respect to THC content; further, the DOT Notice advised that “CBD use is not a legitimate medical explanation for a laboratory-confirmed marijuana positive result.” 86

Notably, airport operators responding to the survey conducted for this project report that determining whether a position qualifies as “safety sensitive” is not always clear. This results in a fairly wide range across airports of which positions are deemed safety sensitive and subject to mandatory drug testing.

It nevertheless remains unacceptable for any safety-sensitive employee subject to the DOT’s drug testing regulations to use marijuana. Since the use of CBD products could lead to a positive

___________________

83 14 C.F.R. § 120.105.

84 12 C.F.R. § 120.109.

85 49 C.F.R. §§ 40.91, 40.137(e)(2).

86 See https://www.transportation.gov/sites/dot.gov/files/2020-02/ODAPC_CBD_Notice.pdf (last visited Jan. 30, 2025).

drug test result, employers should advise their DOT-regulated safety-sensitive employees to exercise caution when considering whether to use CBD products.

b. Other Federal Regulations: Zero-Tolerance and Testing

The FAA and DOT are not the only federal authorities who have issued regulations on drug testing. Federal employees who work in “law enforcement, national security, the protection of life and property, public health or safety, or other functions requiring a high degree of trust and confidence” are subject to mandatory drug testing.87 Various other federal agencies, including the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration, the Department of Defense, and Nuclear Regulatory Commission also have mandatory drug-testing requirements.

Another federal policy that regulates employee marijuana use is the 1970 Occupational Safety and Health Act (“OSHA”). Under OSHA, employers are required to provide a workplace that “is free from recognizable hazards that are causing or likely to cause death or serious harm to employees.” This requirement is also known as OSHA’s General Duty Clause. Tolerating marijuana use by employees—especially in a field where marijuana use can impair necessary judgment—may, in some circumstances, be seen as a harmful work environment.88 This may also require that employers exercise heightened caution and care toward marijuana policies for employees working in safety-sensitive positions, which would include positions were marijuana use could endanger people’s lives and even the national borders. Employers should be cognizant of these issues and evaluate on a case-by-case basis.

c. The Drug-Free Workplace Act

The Drug-Free Workplace Act (“DFWA”) bears special mention, particularly because various entities often mis-cite it as requiring federal contractors to take action that it does not, in fact, require.89 The DFWA requires federal workplaces and federal agency contractors and grantees (with a federal contract of $100,000 or more or a federal grant in any amount)

___________________

87 Exec. Order No. 12,564, 51 Fed. Reg. 32,889 (Sept. 15, 1986).

88 See 29 U.S.C. § 654(a)(1).

89 41 U.S.C. § 8101 et seq.

to maintain a drug-free workplace and implement a drug-free workplace program. The DFWA provides specific actions a federal contractor or grantee must take to ensure and maintain a drug-free workplace.

Under the DFWA, employers must notify employees that “unlawful manufacture, distribution, dispensation, possession, or use of a controlled substance is prohibited” in the workplace and must establish a drug-free awareness program for their employees. A “controlled substance” means a controlled substance in Schedules I through V of Section 202 of the CSA.90 Therefore, the DFWA prohibits marijuana use, because marijuana currently remains a Schedule I substance.

In requiring employers to maintain a drug-free workplace, however, the DFWA does not require applicant or employee drug testing—nor does it require that an employer terminate an employee for failing a drug test for a Schedule I substance like marijuana. Therefore, employers cannot rely on the DFWA in taking certain actions, including, as an example, in terminating an employee for a failed drug test where state law offers that employee protections. Thus, the DFWA would not preempt state law that provides more specific employment-law protections for cannabis users in such instances.

Further to the joint employment discussion in Section IV.A, it is also worth noting that the DFWA does not require federal contractors or grantees to require that their subcontractors or subcontractors’ employees comply with the DFWA. The requirements apply only to workers on the payroll of the federal contractor or grantee. Airport operators should consider this before mandating compliance with the DFWA in their contracts with subcontractors.

d. The Americans with Disabilities Act

The Americans with Disabilities Act (“ADA”) prohibits employers from discriminating against “qualified individuals” on the basis of disability.91 These prohibitions extend to discrimination in many employment actions, including job applications, hiring, training, promotions, compensation, and termination. The ADA further requires employers to make “reasonable accommodations” so that employees with a disability may perform the essential functions of their position. The reasonable accommodation analysis is detailed and situation-specific, but it could require the employer to take steps such as adjusting work schedules or modifying non-essential functions of an employee’s job. An employer subject to the ADA has a duty to engage in an “interactive process” with an employee with a known or apparent disability to determine what the employee’s limitations are and what accommodations might allow the employee to perform the essential functions of her job.

The ADA broadly defines “disability” to mean any physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities. Major life activities include things like breathing, standing, and seeing. Thus, a “qualified individual” with a disability under the ADA may include an employee who takes a prescription drug to manage a medical condition. For example, take the case of an employee whose doctor prescribes a drug to manage a mental health condition. Assume the prescription causes the employee to test positive for a controlled substance on a drug test and makes the employee groggy in the morning. The employer may not be able to discharge the employee for failing a drug test or being late to work. As a reasonable accommodation, the employer may have to grant an exception to its drug testing policy and allow the employee to start work two hours later.

However, a “qualified individual” under the ADA does not include an employee or applicant engaged in the use of illegal drugs. Because marijuana is currently a Schedule I substance under federal law, it remains an illegal drug with no exceptions for medicinal use or protections under the ADA. Therefore, while there may be some employee protections for cannabis use under state law equivalents of the ADA (see next section), an employer is not required to accommodate an employee’s use of medical marijuana under the federal ADA.92

A February 2024 case shows how courts have treated cannabis under the ADA. In Vermont, a transit worker filed a disability discrimination claim under the ADA against his employer when he was terminated for a marijuana-positive drug test. The transit worker was prescribed medical marijuana in accordance with Vermont state law. The federal court granted the employer’s motion to dismiss, reasoning that the transit worker could not rely on the ADA to support his claim for discrimination because marijuana remains an illegal Schedule I drug under federal law—even though medical marijuana is lawful under Vermont law.

While there is an exception under the ADA for illegal drug use when taken under the supervision of a licensed healthcare professional, courts have held that this exception does not apply to medical marijuana use. The U.S. Supreme Court has explained:

In the case of the Controlled Substances Act, the statute reflects a determination that marijuana has no medical benefits worthy of an exception . . . . Whereas some other drugs can be dispensed and prescribed for medical use, see 21 U. S. C. § 829, the same is not true for marijuana. Indeed, for purposes of the Controlled Substances Act, marijuana has ‘no currently accepted medical use’ at all.93

Therefore, while cannabis remains a Schedule I substance, employees are not entitled to accommodations for medical marijuana use under the ADA on the federal level.

Notably, in May 2024, the DEA issued a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking to initiate the rescheduling of marijuana from a Schedule I to a Schedule III drug under the Controlled Substances Act, as discussed in more detail in Section IV.A.2. In the event cannabis becomes a legally prescribable Schedule III drug, employers may have to make reasonable accommodations under the ADA for employees who are prescribed cannabis to treat a disability or medical condition. For example, an employer could not automatically disqualify an applicant who used a

___________________

90 21 U.S.C. § 812(a).

91 42 U.S.C. § 12101 et seq.

92 See, e.g., Skoric v. Vt. Dep’t of Lab. (Marble Valley Reg’l Transit Dist.), No. 2:23-cv-00064-gwc, at *1 (D. Vt. Feb. 14, 2024).

93 United States v. Oakland Cannabis Buyers’ Coop., 532 U.S. 483, 391 (2001).

lawful cannabis prescription to treat a medical condition, even if the employer has a zero-tolerance drug policy; the employer would first need to conduct a reasonable accommodation analysis and determine if it could accommodate the employee’s cannabis usage without an undue hardship. Depending on the position, a reasonable accommodation might include making an exception to a zero-tolerance drug policy, or changing an employee’s schedule to allow him or her time to consume cannabis when their symptoms flair (away from the workplace). Such accommodations may include exceptions to FAA- and DOT-mandated drug testing, though those agencies may issue guidance in the event of a rescheduling. However, such accommodations almost certainly will not require employers to tolerate on-the-job impairment.

2. State Laws

As more states legalize medical and/or adult-use, cannabis usage is creating new questions under existing employment laws. Further, states are also passing laws providing specific protections for employees who use cannabis. This section discusses the most common state-law employment issues related to marijuana use, including the duty to accommodate, state prohibitions against off-duty marijuana use, and drug testing and zero-tolerance policies. A full summary of state cannabis employment laws is in Appendix C.

a. State Disability and Discrimination Laws—Reasonable Accommodations

While current federal law, including the ADA, does not afford employees a right to reasonable accommodations for medical marijuana use, employees may still be entitled to reasonable accommodations under state law.

Several states, including Massachusetts, New Jersey, New Hampshire, New York, and Rhode Island, have various protections that generally require employers to accommodate medical marijuana use outside of the workplace.

In New York, for example, employers with four or more employees are prohibited from terminating or refusing to hire someone on grounds that they are a medical marijuana patient. Further, employers may need to provide reasonable accommodations for medical marijuana use for employees or potential employees who are certified patients under the New York State Human Rights Law.

While in New Jersey, the duty to accommodate is not as broad as in New York, New Jersey state law also has protections that could trigger a duty to accommodate in certain circumstances. In a recent New Jersey case, an employee sued his employer for discrimination under the New Jersey Law Against Discrimination after he was terminated for a failed a drug test while using medical marijuana for cancer treatment.94 The Supreme Court of New Jersey allowed the case to proceed past the pleading stage and into discovery, noting that the employee informed the employer of his disability and his need for treatment and prescription medication.

This decision illustrates that, in states like New Jersey that have state disability discrimination laws and a lawful medical marijuana program, if an employee notifies an employer of lawful medical marijuana use, that notice may trigger a duty to accommodate or, at minimum, engage in the interactive process.

The states requiring accommodations for use of medical marijuana will likely continue to grow as recognition of the drug’s medical benefits increases.

Nevertheless, no state law currently requires that employers accommodate on-the-job possession, use, or impairment while at work. Consistent with state law, 83% (20 of 24 respondents) of survey respondents who reported having existing policies on cannabis or hemp consumption at the airport also reported that the applicable policy disallowed on-duty cannabis or hemp consumption.

Still, because cannabis usage can appear on a drug test days and weeks after any impairment has subsided, employers should rely on other means for taking adverse actions against employees they believe are impaired on the job. This means employers should train supervisors on recognizing and documenting signs of impairment in case they may take adverse action against an employee on that basis.

Further, for employees whose jobs are governed by specific federal laws concerning drug usage, as noted earlier, preemption means that the federal law will control, even if the employee would have otherwise qualified for an accommodation under state law. So, for example, pilots must still test negative for cannabis usage, even if the pilot is based in New Jersey (or another state that recognized the need to accommodate cannabis as a medical treatment) and was prescribed cannabis for a medical condition.

In addition to requiring accommodations for employees who use cannabis to treat medical conditions, numerous states, including Arizona, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, and Virginia, also prohibit employers from discriminating against users on the basis of medical marijuana use or possessing a medical marijuana card—as a distinct matter from the state’s disability accommodation laws.

For example, Arizona’s Medical Marijuana Act (“AMMA”) prohibits employers from discriminating against an applicant or employee based on either “[t]he person’s status as a cardholder,” or “a registered qualifying patient’s positive drug test for marijuana components or metabolites.”95 Notably, the AMMA contains an exception allowing an employer to terminate an employee under those circumstances if “a failure to do so would cause an employer to lose a monetary or licensing related benefit under federal law or regulations.”96

This section of the AMMA was litigated in 2019, when a registered marijuana cardholder sued her employer, Wal-Mart, after Wal-Mart suspended and later terminated her for

___________________

94 Wild v. Carriage Funeral Holdings, Inc., 458 N.J. Super. 416, 420-21 (App. Div. 2019), cert. granted, 238 N.J. 489, 213 A.3d 172 (2019), aff’d but criticized, 241 N.J. 285, 227 A.3d 1206 (2020).

95 ARIZ. REV. STAT. § 36-2813(B).

96 Id.

a marijuana positive drug test.97 In pertinent part, the court sided with the employee on a motion for summary judgment regarding the AMMA discrimination claim. The court reasoned that, while an employer could discipline an employee working under the influence of marijuana, an employer could not terminate a registered cardholder solely for a positive drug test.98

Thus, in these states, a positive drug test, alone, generally will not support a termination or other adverse employment action—even if the employee does not otherwise qualify for disability discrimination protections, unless, of course, state law is preempted (e.g., an employee subject to FAA/DOT drug testing). Again, employers in these states should train supervisors on how to recognize and document the signs of impairment, especially considering that there presently are no standardized, reliable, and commercially available tests for marijuana impairment. More information on cannabis testing and its inability to detect active impairment is discussed later.

b. State Prohibitions on Discrimination Against Off-Duty Adult Use

Increasingly, states are also granting employees protections for off-duty adult-use. As of this writing, California, Connecticut, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, and Washington have laws protecting off-duty adult-use. California and New York have particularly strong protections for off-duty adult-use.