Buzzwords: A Scientist Muses on Sex, Bugs, and Rock 'n' Roll (2000)

Chapter: HOW AN ENTOMOLOGIST SEES SCIENCE

Author! Author! et al.

Ever since I became a department head, I have been a regular reader of The Scientist, a biweekly newspaper that is published by the Institute for Scientific Information in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The free subscription I receive as a consequence of being a department head is, as far as I can tell, the only perk associated with the job (and it doesn 't even come from the campus). The Scientist is the closest thing there is to People Magazine for scientists—it runs feature stories on prominent personalities in science, reports on recipients of scientific awards and prizes, and keeps tabs on research trends. There are obvious differences, of course, between People Magazine and The Scientist. In The Scientist, for example, you find advertisements for real-time digital fluorescence analyzers instead of, say, Ben and Jerry's Ice Cream. Both periodicals publish reviews, but, while a May 1994 issue of People included reviews of upcoming episodes of “MacGyver” and “The New Adventures of Captain Planet,” that same month The Scientist chose to review, among other things, “BDNF mRNA expression in the developing rat brain following kainic acid-induced seizure activity.” And, in all the time I've been reading The Scientist, I've never once seen Oprah Winfrey's picture in it.

What I did see in the April 4, 1994 issue was an article titled, “1993's Top Ten Papers: Superconductor report surfaces in sea of genetics. ” This article listed the “hottest articles in science for 1993—as determined by citation analysis.” Citation analysis is basically the evaluation of bibliographies in published papers. The logic behind counting up citations is that the more people cite a particular publication in their own work, the more interest there is in the paper and the greater its impact —not an unreasonable assumption. Two things struck me about this article on Top Ten Papers as I ran down the list. First, there were no papers on the list with even marginal entomological content. Second, I couldn 't help but notice that no paper had fewer than four authors, and the Number One Most Frequently Cited Paper of 1993, by Rosen et al., had 33 authors.

You won't find the complete citation, with all 33 authors' names, in The Scientist. For that matter, you won't find it in Biological Abstracts, which for years has listed only the first ten or so authors of a multi-author paper. And you probably won't find all 33 names in any textbook in which the paper is cited, because a lot of textbook publishers now are limiting citations to ten or fewer names. I don't even think you'll find all 33 names in the vitae of all of the authors. At least I think if I were, for example, 28th author, I wouldn't want to devote a full half-page of my vita to the 27 names that precede mine.

When you think about it, it's not really so remarkable that Rosen et al. became a citation classic so quickly. Even if each co-author cites it only once in a given year, that's 33 citations right there—although in fairness it must be said that Rosen et al. has been cited 54 times since its publication, so there are 66% more citations than authors. The work itself is unquestionably impor-

tant—the study described in the paper provided a possible causal genetic mechanism to account for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a fatal degenerative disease of the nervous system. But it's not beyond the realm of possibility that multiple authorship can give a paper a boost in the citation department. In fact, for The Scientist's top ten list for 1993, there is a product-moment correlation of 0.62 between author number and citation number, which is marginally significant at p = 0.056. So there's a good chance that a paper with a lot of authors will be cited a lot.

Which then led me to wonder which 1993 entomology paper, on statistical probabilities alone, should be top contender for greatest number of citations. In my search for papers with a large number of authors, I came across a few impressive ones outside of entomology, the most notable being the 42-author study of “Phylogenetics of seed plants: an analysis of nucleotide sequences from the plastid gene rbcL” by Chase et al. in the Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. Then there was the paper by Partsch et al. in Hormone Research (“Comparison of complete and incomplete suppression of pituitary-gonadal activity in girls with central precocious puberty—influence on growth and final height”) with 41 authors. But in terms of papers with entomological content, I was far less successful.

A perfunctory stroll through the unbound journals at the UIUC Biology Library produced only one potential contender for multiple entomological authorship laurels—“Development of recombinant viral insecticides by expression of an insect-specific toxin and insect-specific enzyme in nuclear polyhedrosis viruses” by B. D. Hammock and 12 co-authors. However impressive 13 authors may be among entomological papers, it barely qualifies as a multi-author paper compared with the competition.

The year 1994, however, may have been a bad one for collaborative entomology. Historically, there have been entomological papers with many more authors than 13. Back in 1981, Dr. William Horsfall, my colleague here at the University of Illinois, showed me a paper he had found documenting mosquito distributions in the then-Soviet Union with more than 50 authors. I never did get a copy from him, and I couldn't find it in the library. But it's still out there somewhere, I'm sure, even if the Soviet Union isn't around anymore. Dr. Alan Renwick, of the Boyce Thompson Institute, however, could find (and did share) his copy of Hurter et al., 1987, “Oviposition deterring pheromone in Rhagoletis cerasi L.: Purification and determination of chemical constitution,” in the journal Experientia, with 15 authors. And, according to Dick Beeman of the USDA Grain Research Laboratory in Manhattan, Kansas, fifteen also appears to have been an all-time high for the remarkable E.B. Lillehoj, a research chemist from the USDA Northern Regional Research Center in Peoria, Illinois. While working on aflatoxin contamination of corn and its relationship to corn-infesting insects, Lillehoj was, between 1978 and 1980, senior author of one paper with 15 authors, one paper with 14 authors, and, most remarkably, one paper with 11 authors. The last paper is most remarkable in that the eleven authors worked in 11 different institutions in 11 different states. It's important to point out, to place this achievement in the proper context, that this feat was accomplished long before e-mail was in widespread use.

Multiple authorship wasn't always the rule in entomology. In fact, in the first issue of the Jounral of Economic Entomology, published in 1906, only 6 of the 67 papers had more than a single author (and of those six, none had more than two authors. In fact, 3 of the 6 were co-authored by the same individual, one Wilmon

Newell, a man clearly ahead of his time). In contrast, the December 1993 issue of the same journal contained 34 papers, only 3 of which were by a single author. One paper had seven authors. Even the book review had two authors.

There's a lesson here, apparently—to attract notice today, it doesn't hurt to collaborate. In fact, I would like to encourage entomologists to take a run for the top of the hottest paper list. I should warn you, though, that the competition may be getting tougher, particularly from the medical community. There's a paper in a 1994 issue of New England Journal of Medicine, “Effect of vitamin E and beta carotene on the incidence of lung cancer and other cancers in male smokers,” with 52 authors, and another paper, on clinical trials of a clot-buster drug used in coronary angioplasty, with at least 175 authors (I stopped counting after a while). This is a level of collaboration that may prove unbeatable by entomologists. I don't think even Lillehoj could rise to this challenge.

I'm okay– are you O.K.?

Several years ago, I attended a symposium in West Lafayette, Indiana, on cytochrome P450s. P450s make up a multigene family of proteins that in insects are involved in pheromone synthesis and metabolism of xenobiotics, among other things. I was scheduled to give the fifth talk of the day, a slot for which, on that occasion, I was particularly grateful. For one thing, it wasn't the slot immediately after lunch when people fall asleep; it also wasn't the last talk of day when the audience would include only those driving home with me in the same vehicle. Most importantly, on this occasion I was relieved to be giving the fifth talk of the day because, despite having published papers on insect P450s for more than a decade, I wasn't exactly sure how to pronounce them.

Back when I first got interested in these enzymes, they were called MFOs—mixed function oxidases—because they catalyze a variety of oxidative reactions. Unbeknownst to me at the time, the powers that be had decided the name was not descriptive enough and these enzymes should from that point on be known as PSMOs, or polysubstrate monooxygenases, because they attach a single oxygen atom to many different substrates. By the early

1990s, an elaborate system of standardized nomenclature was advanced whereby these enzymes were classified into families and subfamilies, based on degree of protein sequence similarity. Now, P450s are referred to by the acronym CYP, for CYtochrome P-450. This acronym is followed by a number, which designates a gene family (#DXGT#40% sequence identity); the number is followed by a capital letter, designating the gene subfamily (#DXGT#55% sequence identity), and the letter is followed by yet another number, to designate a particular gene. If there are allelic variants of the gene (#DXGT#97% sequence identity), the number is followed by a lower case v (for “variant”), in turn followed by another number. Thus, when we cloned and sequenced a cytochrome P450 from the black swallowtail caterpillar Papilio polyxenes, it became known as CYP6B1v1—a member of family 6, to which belonged the first insect P450 cDNA to be cloned, but sufficiently different from said P450 to merit its own subfamily, 6B.

My biggest concern about presenting a paper at this particular meeting is that I wasn't sure how to pronounce “CYP6B1.” Around the lab, we called this enzyme “sip-six-bee-one” but I really wasn't certain this was de rigeur among those in the know. I was exceedingly relieved when the first speaker of the day at West Lafayette, Paul Ortiz de Montellano, a highly respected figure in the field from University of California at San Francisco, began talking about “sip-1A1” and other mammalian P450s. My relief lasted only until the beginning of the second talk, when that speaker stood up and started describing his work on cytokine-mediated inhibition of “sipe-17” expression. For the record, the third speaker referred to his family of proteins with the descriptor “see-wye-pee.” I confess that, by that point, I was too distressed to listen to the fourth talk at all.

While acronyms have probably always been with us in biology, they 've kind of been getting out of control lately. Time was when acronyms were more or less the exclusive province of electrical engineering. Remember SONAR? And LASER? But ever since the genetic material was discovered to be something with the exceptionally unwieldy name of deoxyribonucleic acid, biologists have gone in for acronyms (such as the classic “DNA”) in a big way. Molecular biology is without doubt the most acronym-intensive area of contemporary biology. This field not only has acronyms, it has synonyms for acronyms. The external non-transcribed spacers (ENS) between ribosomal RNA genes, for example, are also known as the IGS, or intergenic spacers, and as the NTS, or non-transcribed spaces. For that matter, this field has acronyms made up of other acronyms. In Drosophila, some proteins contain a 270-amino acid motif that appears to facilitate self-association. When this motif was found in the period gene product (PER), in the aryl hydrocarbon nuclear translocator (ARNT) (a component of the dioxin receptor complex), and in the single-minded gene product (SIM), it was only natural to refer to it as the PAS domain (from PER-ARNT-SIM). The world hasn't seen this kind of acronym use since the days of the KGB in the USSR at the height of the Cold War.

I think excessive acronym use might be one of the reasons I am often slightly uncomfortable when reading articles dealing with molecular biology. There are always so many CAPITALIZED acronyms in the text —reading these WORDS in big letters makes it SEEM like the author is very ANGRY for some reason. Take, for example, the issue of Science from September 22, 1995, which happens to be sitting unfiled on my desk at the moment (along with other scattered issues of Science going back to 1981, when I

first moved into this office). The page called “This Week in Science” describes highlights of the issue. The highlights include reports on control of contraction in muscle cells by Ca2+ release by the SR (sarcoplasmic reticulum), on control of protein phosphorylation and T cell proliferation by the chemokine RANTES, on regulation of IFN (interferon)-induced transcription by MAP (mitogen-activated protein) kinase (making it a STAT, or signal transducer and activator of transcription), on PSD-95 (a postsynaptic density protein), which interacts with a type of NMDA (N-methyl D-aspartate) receptor, and on the role of nAChRs (N-acetylcholine receptors) in the CNS (what nervous system?). The acronyms on the page seem to be shouting out for attention, STAT! These are not mere pleas for attention, they are RANTES!

The trend is clear—acronyms will not only not go away, they will infiltrate all areas of biology, including entomology. They've long been entrenched in insect physiology (e.g., the source of cellular energy, adenosine triphosphate, ATP, formerly known as TPN). Insect systematists use them with increasing frequency, not only to describe the methods they use to obtain data (e.g., SDS-PAGE, RFLP, RAPD), but also the methods they use to analyze their data (PHYLIP, PAUP). Systematists in fact may have gotten the whole acronym ball rolling centuries ago by adopting the convention of abbreviating the genus name when referring to a species. Nowadays, the bacterium E. coli and the nematode C. elegans barely have first names anymore, although for whatever reason Drosophila melanogaster has resolutely defied abbreviations. Even ethology has heeded the call, what with the Evolutionarily Stable Strategy generally referred to as an ESS.

About the only discipline in which acronyms are truly unusual is ecology. There, they are certainly few and far between. There

are a few in population biology that I confess have long baffled me—why, for example, is “carrying capacity” designated “K” instead of “c” or “CC”? And the intrinsic rate of growth is known rather too concisely as “r” (pronounced “little are”)—why, historically, was it never IRR? Why lower case r in the first place? Was it an uncommon fear of attracting attention?

Acronyms in ecology also don't seem to have much longevity (sometimes designated lx in life table analyses), either. My UIUC colleague Gilbert Waldbauer was successful back in 1968 in introducing a panoply of acronyms for discussions of ecophysiology. In a widely cited review of gravimetric estimates of nutritional performance, Waldbauer established the parameters ECI (efficiency of conversion of ingested food), ECD (efficiency of conversion of digested food), RGR (relative growth rate), RCR (relative consumption rate), and AD (approximate digestibility). But the future of these acronyms is in doubt, thanks to several recent publications by statistically minded biologists questioning the calculations upon which the acronyms are based. If these critics prevail, no longer will insect ecology students have acronyms to worry about while studying for midterm exams; knowing what ECD stands for will no longer mean the difference between an A and a B.

This undue reserve acronym-wise may put ecologists at a significant disadvantage in terms of competing in today's scientific world. I would argue it's a bad time for anyone to start expunging acronyms from their discipline. I can't help noticing that the allocation of federal research dollars to biological subdisciplines appears to be highly correlated with acronym use. Molecular biology, e.g., receives the lion's share and ecology, systematics, ethology, and other acronym-poor programs are suffering deep

cuts. Whether this relationship is causative I can't really say. I do feel compelled to point out, though, that it wouldn 't be inconsistent behavior from agencies widely known by their initials, NSF, NIH, USDA, and DOE. Coincidence? I don't think so. In fact, as an insect ecologist, I think I will devote some time developing some acronyms as soon as possible (ASAP), before the next request for proposals (RFP) is issued by the National Science Foundation (NSF).

“Quite without redeeming quality?”

You might think that, after 20 years as an independent professional scientist, I'd be pretty much inured to criticism. After all, the review process is intrinsic to the conduct of contemporary science. Grant proposals are scrutinized by panels and ad hoc reviewers, manuscripts are criticized by reviewers and editors, and even course lectures are evaluated at the end of the semester by undergraduate students. I'm certainly no stranger to negative remarks, either—I've had my share over the past two decades. I actually keep all of my reviews, favorable and unfavorable, in a file cabinet in my office (they now fill two complete drawers) and read through them again every now and then. Even favorable reviews tend to have a few critical remarks, and it's almost always the case that even the most negative reviews I've received have had some merit to them, some constructive comments, no matter how inelegantly these comments have been phrased. The one that stands out as being particularly brutal was a review I received for a manuscript submitted to Apidologie (and eventually published, after extensive revision, in another journal). In the course of a single paragraph, this reviewer managed to use the words “inadequate,” “naive,” “superficial,” and “farcical,” as well

as the phrase “quite without redeeming quality.” Mercifully, most people tend to be a little more circumspect in their choice of adjectives. Conservatively, I can say I've received more than a hundred bad reviews over the course of my scientific career to date, counting just manuscripts and grant proposals. I console myself with the knowledge that not even Michael Jordan made every basket he shot for, either, and I regard every bad review as a learning experience.

Notwithstanding all of my experience in this context, I confess I was completely unprepared for a bad review that I received in 1998. Ironically enough, the review was directly related to my “Buzzwords ” essays. In a fit of egotism, I thought that it might be a good idea to collect all of the columns I had written for American Entomologist and submit them to a publisher, in the hope of converting them into a book. Such an idea is hardly radical—a number of columnists, even those writing on scientific subjects, routinely publish their essays in book form (Steven J. Gould comes immediately to mind). Because I knew that Cornell University Press (CUP) has a history of publishing such works, and because I ran into Peter Prescott, the CUP acquisitions editor, at the Entomological Society of America meeting in Nashville in December 1997, it seemed like a good idea to bundle together the columns and send them off to Cornell University Press for appraisal. As all good editors should, Peter Prescott sent the package out for review. The first review came back quickly and was quite positive; I figured this was going to be easy. The second review, however, completely threw me. The reviewer, self-described as an entomologist who had taught and conducted research at a land-grant university for 40 years (and therefore eminently entitled to an expert opinion), was breathtakingly

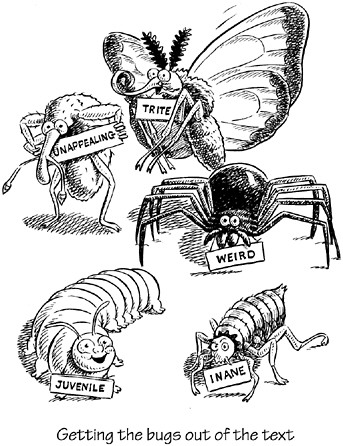

unimpressed with “Buzzwords.” He described some of the essays as “inane” and apparently found references to “orifices, sex, and other basic bodily parts and functions” unappealing. “Little conceptual matter of any depth” was another phrase that appeared in the review, threatening to displace “farcical” as the most depressing criticism I've ever received.

I couldn't even take solace that this opinion might be an exceptional one. This reviewer, in a frenzy of thoroughness, polled a group of his or her entomological colleagues (also eminently entitled to expert opinions) and found, of 19 who knew of the columns, three who did not like them at all. Of those who admitted to liking the columns, none were reported to be “ebullient” in their praise. In contrast, those who did not like the columns were free with their use of adjectives and offered up words such as “trite,” “weird,” and “juvenile” to describe them.

Maybe ego is to blame, here, but it really never occurred to me that people might detest these essays. I always figured that a few people would ignore them, but I never thought they might be utterly despised. Reading this review was like discovering, in the middle of a prestigious lecture in a packed hall, that my pants zipper was undone and that audience members who were laughing were not marveling at my fine sense of humor but rather at my choice of undergarments that morning.

In short, after reading this review (over and over again) I became acutely self-conscious and acquired a major case of writer's block. The reason for the writer's block was that, as always, this negative review contained a considerable amount of truth. When I write, I do tend to go into orifices, as it were, with greater regularity than the vast bulk of entomological writers (although, if anything had “depth,” one would think orifices would). My sense of humor

Getting the bugs out of the text

does on occasion slip from lofty to low-brow. I soon began to obsess over every word and wonder how I might recognize “trite” or “inane” whenever it crept into my writing. But after a couple of months, it struck me that the criticism was a little unfair. The humor may well be juvenile, but I happen to know it's not nearly as juvenile as it could be. As a matter of fact, there are several subjects I've refrained from writing about expressly because they seemed to me to be too juvenile. And, just to prove the point, I'll share them with you now.

Here are four ideas I personally rejected as being too trite, juvenile, or tasteless to follow up on, even before explicit recognition of my shortcomings was thrust upon me.

-

According to Partridge (1974), there is an assortment of colorful turns of phrase that metaphorically associate insects with the act of masturbation, including “to box the Jesuit and get cockroaches ” and “to gallop one's maggot.”

-

In an article titled “Perfectly inflated genitalia every time,” Nolch (1997) describes the development of the vesica everter, or “phalloblaster,” developed by I. W. D. Engineering and the Australian CSIRO Division of Entomology. According to Dr. Marcus Matthews, quoted in the article, “The vesica everter inflates the genitalia with a stream of pressurised absolute alcohol which dehydrates and hardens the genitalia. . . . They then remain inflated like a balloon which never goes down. ” As a point of clarification, I should mention that the phalloblaster was designed for use only with insect genitalia.

-

Dangerfield and Mosugelo (1997) in an article titled “Termite foraging on toilet roll baits in semi-arid savanna, South-East Botswana (Isoptera: Termitidae),” describe a method for surveying termite abundance with the use of “single-ply, unscented toilet rolls ” as bait. According to the methods, each role is “placed in an augured hole,” not to be “even” with the soil, or to be “level” with the soil, but to be “flush with the soil.”

-

Following up on earlier reports that the yellow fever mosquito Anopheles gambiae is highly attracted to the odor of Limburger cheese, which bears a strong resemblance to the odor of (some) human feet, Knols et al. (1997) were able to produce a synthetic Limburger cheese (or foot) odor by characterizing the

-

chemical components of Limburger cheese headspace. Again, as clarification, cheese headspace is the volatile milieu immediately surrounding the Limburger, not the empty seat next to a guy wearing a funny hat at a Green Bay Packers game.

Any one of these topics would have made for an incredibly tasteless column, and, up to this point, I have restrained myself from succumbing to the temptation to get really sophomoric. Truth be told, though, it was more than just good taste that led to this restraint. I really don't think I could stand reading the reviews I might get if I actually went ahead with one of these ideas.

Flintstones 101

As the result of an accident of birth, I belong to a generally overlooked demographic group; born in 1953, I am among that elite group of scientists who were the first to grow up watching television. In 1948, television sales had surpassed sales of radios, and by 1955, when I was two years old, close to 2/3 of all American households had a television set. And I did watch a lot of television as a child. Among the more memorable of the programs I watched was “The Flintstones,” which originally aired from 1960 to 1966 and is now still seen on cable stations almost around the clock in reruns. The Flintstones was something of a record-setter at the time; it was the first animated sitcom, it was the first animated 30-minute show, and it was the first animated series to feature human characters. I'd like to think I recognized it for what it was, which was an animated version of the sitcom “The Honeymooners.” Evidently, though, many of my contemporaries apparently believed that they were watching a documentary. In a survey of science literacy conducted by the American Museum of Natural History in 1994, some 35% of adults polled believed that prehistoric humans coexisted with dinosaurs and another 14% thought it might be a possibility. Experts other than William

Hanna and Joe Barbera believe that dinosaurs went extinct at the end of the Cretaceous, some 65 million years ago, whereas protohominids don't even appear in the fossil record until, conservatively speaking, 10 to 20 million years ago and true hominids not until about 4 or 5 million years ago.

Sixy million years is more than a minor detail but it's just one example of the problem of science literacy in the U.S. It's entirely likely that the 49% of adults surveyed by the American Museum of Natural History had at some point in their lives heard that dinosaurs and humans didn't cohabit. Most likely they heard it in school—I remember distinctly my fourth grade teacher, Mr. Parker, discussing the issue—but for whatever reason it didn't register. It's a safe bet, however, that the majority of those very same adults could recognize the theme song from “The Flintstones ” if not sing along to it in its entirety.

So why is it that science is so hard to remember? One possible reason is that it's boring—or at least it's perceived by the vast majority as such. There's no question that most find it boring in school. Innumerable studies have revealed that students find the way science is taught in school to be insufferably dull. Recent examples include:

-

An Office of Technology Assessment study conducted in 1988, called Educating Scientists and Engineers; Grade School to Grad School, in which high school students polled by Harvard's Educational Technology Center agreed overwhelmingly that science is “important but boring.”

-

A recent study of Why Students Leave undergraduate science majors, in which authors Seymour and Hewitt report that the proportion of undergraduates remaining in science majors is

-

substantially lower than the proportion remaining in social science or humanities majors, and the principal reason these students switched majors (mostly out of science altogether) was that they were “turned off” or bored by science.

It's unquestionable that there are problems in the classroom and there are major efforts under way to reform science education in schools. There have been for years, in fact; headlines from 10 and 20 years ago recognized the same crisis that is freely discussed in the press today. The repeatedly poor performance of American eighth graders in the Third International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) relative to other eighth graders in 40 other countries invariably stimulates rounds of discussion in science and education journals alike (only 13% of U.S. students scored in the top 10% of 300,000 students in 1996). But while it's necessary to reform science education in schools, it's not sufficient. The reason it's not sufficient is that the amount of exposure to science that average Americans receive in school is literally an eyeblink over the course of their lives: a few hours a week in primary school and, over their four-year college careers, maybe, if they 're lucky (or unlucky, depending on perspective), one course of 44 lectures in biological science and one course of 44 lectures in physical science. That's six hours out of a minimum 120 (5%). For biology, that translates to 35 literal hours of lecture (no labs required) over an entire undergraduate career, not counting classes missed due to rainy days, oversleeping, days that are too nice to go to class, the Friday before spring break, the Wednesday before the Friday before spring break, and other exigencies of undergraduate life.

Where, then, do these students get exposed to science, out of school and after graduation? The chief source of science

information over the lifetime of the average American is, most likely, television. Unlike mandatory school attendance, which has held steadily constant for many years, the number of hours spent watching television has been steadily increasing. The three or four 50-minute periods per week of science education required by enlightened school districts at the elementary and middle school level pale into insignificance compared to the average 12-14 hours of television-watching per week these same students engage in. Once the semester ends, and once students graduate, it's all television, newspaper, and other media, except for perhaps the very occasional public lecture.

It's not that learning from television is a bad thing—I've learned a lot from television. I learned, e.g., how to spell “polo pony” from a memorable Flintstones episode where Fred plays scrabble. But there's a problem. Science on television is boring. Joe Queenan, a TV commentator for TV Guide, the most widely read periodical in the U.S., once proposed a new rating system for TV (April 25, 1997), with “TVB” as a viewer advisory for boring shows—such as science documentaries and speeches by Vice President Al Gore. There's definitely a rut out there. I surveyed titles in the Teachers Video catalogue, a compilation of among the best science documentaries available on video, and found that almost 90% of titles are either nouns + prepositional phrases (“Kingdom of the Sea Horse”), single nouns (“Tornado!”), or adjective + noun (“Invisible World”). It's likely that no other form of entertainment displays such depressing uniformity. Titles from other forms of film, e.g., are rife with alliteration, puns, literary references, and puncutation marks other than colons. Take soft-core porn film titles; a quick review of a video catalogue reveals alliteration (“Beach Babes From Beyond”), allusion (“Oddly Coupled,”

“Midnight Ploughboy,” and “Thigh Noon”), and puns (“Dracula Sucks”).

Why should anyone bother about reaching out to the masses? First of all, there's a vast potential audience out there for a good production, and there is a lot of money to be made. Carl Sagan's “Cosmos” series attracted more than 500 million viewers over its run. With those audiences, sales potential isn't too shabby—the Stauffer brothers, e.g., sold close to $20 million worth of nature videos in a three-year period and the David Attenborough “Life on Earth” series generated more than $20 million in revenue in its day. That's not even considering the potential for merchandising. “Magic School Bus,” a PBS program aimed at teaching science to kids, managed to partner with McDonald's to put science into Happy Meals. Of course, the lines for Ms. Frizzle and her entourage weren't nearly as long as they were for Teeny Beanie Babies, but it's a start.

There's a more important reason, too, for becoming involved in the production of high quality accurate AND entertaining science programming. I think everyone recognizes that in a democracy everyone is better off if the majority of voters are well informed. An increasing number of laws and referenda deal with issues that involve science. Poll after poll demonstrates that Americans feel it's important to be well-educated in science. The American Museum of Natural History study (1994) revealed that 76% of the 1,200+ individuals polled admitted to enjoying learning about science for its own sake. And a 1991 SIPI/Harris Poll showed that the level of interest in the general public runs as high as 80% for certain issues of science or policy. And a 1996 study conducted through the Chicago Academy of Sciences on Public Understanding of Science and Technology demonstrated the broad gap between

science interest and science knowledge here in the U.S., compared with most other nations.

Most people recognize that, to deal with complex issues, they need information. For the most part, they're willing and eager to be educated and it's important for scientists to give them what they want and need, or to work with media professionals to do it. Otherwise, we all run the risk of allowing tabloid newspapers to determine science policy and living with the consequences. After all, do we really want to count on”Weekly World News Readers” to “Shrink Holes in Ozone Layer—With Their Minds!”?

A word to freshmen

In late summer a massive human migration begins, one without parallel in the natural world. From all over the country, adolescents and young adults depart their family homes and set off for college campuses of all descriptions. They arrive on these campuses burdened not only with the necessities of college life—pillows, desk lamps, and hot plates—and the accoutrements of higher learning—textbooks, personal computers, pencils, and erasers—but also with an amazing number of preconceived notions about what college life will be like. A distressing number of these preconceived notions focus on a group of people that is, to incoming freshmen, something of an enigma—college professors.

Incoming freshmen can hardly be blamed for having a few odd ideas about what exactly it is that a professor does. The vast majority, in all likelihood, have never met one. It's not like there are professors living in most cities or towns in the U.S. If you look in the Yellow Pages of whatever town you're from, you almost certainly won't find a listing for “Professors,” like you do for auto mechanics, taxidermists, dance instructors, veterinarians, taxi drivers, and other overtly useful people. In fact, even here in

Champaign-Urbana, a town crawling with professors, you won't find “Professors” in the Yellow Page between “Process Servers” and “Prosthetic Device,” where you might expect to find them (alphabetically, that is).

So most freshmen arrive on campus without any personal experience to guide their impressions. It's not that they lack impressions. Unfortunately, the one source of information people are most likely to use in formulating their image of a professor is television and I'm not certain that television is the best source of information on which to build any sort of impression. A quick check around the dial illustrates the point. If, for example, your tastes run to comedies, you may have the impression that professors are like Professor Julius F. Kelp, as portrayed by Jerry Lewis in the 1963 film, “The Nutty Professor”—a socially inept, inoffensive fellow who uses his powerful intellect and scientific expertise to perfect a chemical formula that can turn himself into a lounge singer—the suave and sophisticated Buddy Love, bon vivant and man about town who is irresistible to women, including female students in his classes (the fact that he ends up dating them would likely have him hauled up before his Dean on harassment charges today). If not Buddy Love, you might have the impression that college professors are just like Professor Ned Brainard (Fred MacMurray), the absent-minded professor from the 1961 film of the same name—another socially inept inoffensive fellow who develops a chemical formula for flying rubber that he uses to help his college 's basketball team win The Big Game. Now, I'm not exactly an authority on the subject but my guess is that the NCAA would probably frown on this sort of thing if they found out about it.

Sci-fi fans can base their impressions on the 1958 cult classic,

“Monster on the Campus” about Dr. Donald Blake (Arthur Franz), well-intentioned scientist and researcher at Dunsfield University who, by virtue of exceptionally bad laboratory technique, inadvertently gets exposed to the blood of a Carboniferous era fish (through some amazing plot contrivances, he ends up smoking it) and turns into a primitive raging violent humanoid mutant. This film, by the way, was once reviewed by the New York Times as “summa cum lousy.” If you're a fan of adventure films, then you can see Harrison Ford as Indiana Jones, the anthropology professor who, over the course of his academic and movie career, found the Ark of the Covenant, saved the Holy Grail from Nazis, and rescued people from the Temple of Doom sustained only on occasional meals of monkey brains and scarab beetles. Or maybe you can see Sam Neill as the paleontologist in “Jurassic Park, ” who saves the world from rampaging velociraptors, presumably in between cataloguing fossils and grading term papers.

So, based on your television viewing habits, you might think professors are bumbling misfits, superheroes, or twisted deviates. And, whatever other category they belong to, at least in the movies, they are also all white males. The reality is, to be perfectly frank, a lot duller in almost every respect. A demographic breakdown of the UIUC faculty quickly dispenses with the notion at least that professors are invariably aging white males. While the ratio isn't exactly 50:50, as it is in the public at large, it's a lot better than it was back in Julius Kelp's day. And while most of the faculty aren't exactly Generation X-ers, neither are they old enough to have accompanied Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders on the charge up San Juan Hill. Nor is the UIUC faculty all-white, either; there are African-Americans, Latinos, Asians, and Native Americans among the ranks.

Demographic data obtained from censuses don't really provide much information on the number of superheroes or fiends on the campus, nor do they shed much light on degree of social ineptitude. Data that could be informative in this context are very hard to collect and I was unsuccessful in obtaining these data from the campus; after all, it's not as if the central administration can pass out questionnaires with questions like, “I am a dweeb—yes, no, uncertain. ” In an attempt to fill the gap at least a little, I collected some information from the faculty in my own department, the Department of Entomology in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

-

Each faculty member on average has a single spouse and 1.88 children; cats are the most popular pets (and, just to update this survey, which was conducted some time ago, I regret to say that the untimely death of Flounder, the guppy, has reduced the number of faculty with fish from three to two).

-

Hobbies run the gamut from stamp and coin collecting (hobbies Julius Kelp would undoubtedly have appreciated) to decidedly less dweeb-like tae kwan do and wind surfing.

-

In terms of musical tastes, while admittedly there is a conspicuous absence of contemporary groups among the favorites (no Barenaked Ladies or Nine-Inch-Nails yet), variance is very high and runs from sublime (Chicago Symphony) to ridiculous (Herman's Hermits).

If these data do show a pattern, it's that the faculty, even in a tiny department, are a variable lot. With such variability, generalizing is a risky business. It's too often been the case that incoming freshmen have assembled bits and pieces of information gathered

from media and from friends and brought with them prejudices that lead them to major misconceptions about the college professor, here as well as at other institutions. I'd like to take this opportunity to reveal the most common of these misconceptions for what they are.

-

POPULAR MISCONCEPTION NO. 1. Professors prefer to think of their students as numbers rather than as individuals with personalities and even names. Professors probably don't even name their own kids, they just refer to them by the last four digits of their social security numbers.

It's true that there are big classes at public universities and, for logistical reasons, numbers are necessary. And it's true that most professors don't make an effort to learn the names of all students in classes with 500 or more of them. But I don't know anyone who doesn't want to get to know his or her students; oftentimes that's difficult to do because students are so reluctant to approach their professor, even to ask a question. In a small class, odds are very good that your professor will learn your name, and maybe even remember it years hence. In a large class, it's hard to say—but, as a general rule of thumb, whether or not a professor learns to recognize you, remember you, and address you by name depends a great deal on how much effort you put into the class. I would like to add, on behalf of my colleagues, that it's very hard for us to learn to recognize you and address you by name if you never come to class.

-

—POPULAR MISCONCEPTION NO. 2. Professors at a prestigious universities like to conduct Important Research; this Important

-

Research has no useful purpose other than to ensure that the Professor conducting it gets tenure, at which point he or she no longer needs to do it anymore.

Again, activities of the faculty here dispel this notion quickly; research conducted by UIUC faculty, as a case in point, has affected the lives of an enormous number of people. The light-emitting diodes in digital clocks, transistors in transistor radios, Illini supersweet corn at July 4th picnics, the soundtracks on movies at the movie theater, the insecticide in the flea powder you sprinkle on your dog, the software you use to surf the Internet, the biodegradable packing material in the present your grandmother mailed you on your last birthday—all were based on research conducted by UIUC faculty. Among the most satisfying aspects of research in any field is to see your work cited and used by others, not buried and forgotten in obscure journals that not even the University of Illinois Library can afford to subscribe to anymore. UIUC is not by any means unique —just about any public university can boast of an equivalent list of accomplishments. I remember a high point in graduate school at Cornell being the moment I realized that I was standing in a lunch line behind the man who invented the turkey hot dog.

-

POPULAR MISCONCEPTION NO. 3. Professors lead such empty and meaningless lives that their sole source of pleasure is taking points away from students on exams. What they do with all of these points they take away is a baffling mystery, although it's been suggested that they store them in huge vaults and go count them at the end of the semester.

In point of fact, most professors don't like taking points off a

student's exam. If you think about it, it requires far more effort to take points off than not to take points off. The easiest kind of exam to grade is one that's perfect. Not only is it easier, it's also a lot less depressing. I personally rejoice when a student achieves a perfect exam score in a course I'm teaching because I can take that score to mean I've been effective in transferring information to that student. So students do everyone a favor when they study and get as many answers right as they can.

-

POPULAR MISCONCEPTION NO. 4. Professors are intentionally boring. They would have to be working at it to be as boring as they actually are. Professors who are interesting get fired from the university because they have violated the first rule of academic classroom performance—if it's not boring, it can't be educational (like medicine, which can't be effective if it doesn't taste bad).

I have to admit that you will encounter some professors whom you will find boring. But then again, odds are good that other students in the same class may find that same professor absolutely fascinating. There are as many styles of teaching as there are faculty members and, just like you may not like all 31 flavors of Baskin-Robbins ice cream, you might not like everybody's teaching style. Most of the faculty I know try very hard NOT to be boring, in the classroom or in their lives outside the classroom. Imagine if you were having a conversation with someone and before you could finish what you were saying that person started snoring—I can assure you, there is nothing more demoralizing than looking out and seeing even one student asleep during your lecture.

There are many more misconceptions, but to list them ad nauseum would just belabor the point—the point being that, through your academic career, you should try to keep an open mind about professors. We 're as different from each other as each of you is from anyone else in the world (although an exception may have to be made for sibling professors who are identical twins). There is one thing, though, that we all have in common—at one point in our lives, we were all college freshmen. It may have been a long, long time ago for some of us, but we've been there—there are some things one never forgets. So get to know us if you can—you might be amazed at what you find out. Some of my best memories of my college days, believe it or not, involve the professors I met there—the ones who taught inspiring courses, who took a personal interest in my career, and who in countless ways helped me become, for better or worse, the person I am. I wish you many such memories to come. By the way, don't worry—you won't be tested on this material four years from now . . . and yes, the final is cumulative.

Holding the bag

In his masterful autobiography, Naturalist, the great evolutionary biologist Edward O. Wilson speculated that physical limitations can determine the course of a life. In his case, a painfully close encounter with a pinfish during a childhood fishing expedition left him with a left eye that couldn't focus at long distances; not coincidentally, he devoted his career to the study of ants and other small creatures that require magnification for close observation. I am an enthusiastic subscriber to this theory, because I know of at least one physical infirmity that I possess that has influenced the course of my own career. This particular limitation did not arise as a result of a dramatic conflict with nature; rather, it seems to have been an accident of genetics. I've spent my entire research career to date working on organisms that live within walking distance of the laboratory because, since before I can remember, I've been exceedingly prone to motion sickness.

Motion sickness, as you most likely know, results from a genetic inner ear imbalance. Everyone experiences motion sickness at some point in their life—deep sea fishing or shuttle launches can usually unsettle even the strongest of stomachs. My threshold is a lot lower. Not only did I get car-sick with depressing regularity as

a child, I also, on various occasions, got elevator-sick, train-sick, bus-sick, ferry-sick, rowboat-sick, and, on one memorable occasion, bicycle-sick. There are times when I swear that continental drift is making me motion-sick. A motion-sickness bag was always at the ready in the glove compartment of my parents' cars throughout my entire childhood; to this day, I make sure I carry one with me whenever I know I'll be in a moving vehicle for more than ten minutes. I may forget to pack my lecture notes or bring the wrong set of slides when I leave for a trip, but I always have my bag with me (not that it's a big help at seminar time when I have brought the wrong slides).

Despite parental reassurances that I would outgrow this unsettling tendency, it hasn't happened yet. As a consequence, many aspects of my professional life have been affected. The traveling I do to conferences and seminars is a constant source of apprehension and, to some degree, aversion. Most recently, I gave a twenty-dollar tip, over and above a 20% tip, to the limo driver who took me from Oxford, Ohio, where I'd given a lecture at Miami University the day before, to the Cincinnati airport because I threw up in his beautiful, brand-new, boat-like Lincoln Town car. Colleagues think I'm an exercise fanatic because I prefer to walk a mile-and-a-half from the hotel to a conference center; they don't know that subway trains and taxis in stop-and-go city traffic are more than my system can handle. And, when the Entomological Society of America had its annual meeting in the Las Vegas Hilton Hotel, I declined to join my colleagues in the Star Trek Experience not because there was an interesting symposium I didn't want to miss but because I thought simulated warp drive would push me over the edge. As for choice of field sites, no tropical rainforests for me —my field sites are for the most part less than fifteen

minutes away from the lab. And even in my office, susceptibility to motion sickness affects many daily decisions; I don't have a screensaver on my computer because the sight of flying toasters turns my stomach.

As a biologist, I can't help wondering what nasty trick of evolutionary physiology has forged a connection between perceived aberrant motion and vomiting. As far as I know, there has only been a single paper published on the subject. In 1973, Michel Treisman published a paper in Science titled, “Motion sickness: an evoutionary hypothesis.” Treisman notes that motion sickness is triggered by conflict among the sensory inputs by which humans determine their location in physical space: the visual frame of reference provided by input from the eyes, orientation of the head as indicated by vestibular receptors in the ears, and relationships among body parts as indicated by non-vestibular proprioceptors. Inconsistencies among these inputs can be realigned to some degree, by head or eye movements, or compensatory movements of trunk and limbs. Modern life, however, provides inconsistent inputs that exceed the adaptational capacity of the system. Traveling at speeds in excess of 60 miles per hour (or, even more dramatically, 600 mph in an airplane) can cause sensory conflict that is not easily resolved by realignment of the head or alteration in patterns of eye movement.

As to why such conflict should lead to vomiting, Treisman suggests that, in our evolutionary history, the stimulus most likely to produce discordance among the major sensory inputs is ingestion of a nerve poison, or neurotoxin. Plants are rich sources of substances that disrupt normal neurological function (as I write this at 3 a.m. in an agitated state directly attributable to the consumption of caffeine-laden Dr Pepper at lunchtime). An

emetic, or vomiting, response to a mismatch between inputs is adaptive in this context in that it provides the body with a mechanism for removing neurotoxins from the system. The author goes on to suggest that the malaise and “marked depression” that often accompany motion sickness may be adaptive as well, that in our evolutionary past such aversive responses would serve to reduce the probability of future encounters with the source of the nausea-inducing material. I expect there is some truth to this notion; if I ever go back to Miami University I definitely will check to see if there's another limo service in town.

Treisman also reports that humans are not alone in their tendency to experience motion sickness—monkeys, horses, sheep, some birds, “and even codfish” (but “not rabbits or guinea pigs”) are prone to motion sickness. This raises the question as to how one recognizes motion sickness in nonhuman species. In humans, the principal manifestations are pallor, sweating, and vomiting. I don 't know if fish can sweat, but I'm certain that horses can't vomit—that's one reason they are so prone to colic, or intestinal difficulties. And I'm not sure how one determines whether a sheep looks pallid or not. Assuming motion sickness can be recognized when it appears, I'm not convinced that the taxonomic distribution of motion sickness is supportive of the hypothesis. Among the nonhuman model systems used for the experimental study of motion sickness are carnivores such as cats, dogs, and ferrets, omnivores such as rats, and an insectivore known as Suncus murinus, all species unlikely to ingest plant toxins (although some insects produce neurotoxic defense secretions and carrion may contain some nasty toxins as well).

I find this literature fascinating, and I would love to explore the subject in greater depth, but here's where physical limitations enter

in again. I find I can't read statements such as “ingestion of warm yoghurt intensified nausea during Coriolus stimulation in a rotating chair” (Feinle et al., 1995) without slamming the paper down and running to the bathroom. I happily leave the study of motion sickness, and the warm yoghurt, for that matter, to those with more adept vestibular sensory systems and stronger stomachs than I possess.

Kids Pour Coffee on Fat Girl Scouts

We're all products of the era in which we grew up. That I came of age during the 1960s and attended college in the 1970s I suppose is reflected in my dress and appearance—with jeans (which my high school didn't allow girls to wear until senior year) and long hair (which my parents wouldn't allow me to have until I moved away to college). That I still dress like a college student isn't so much a smoldering rebellion against a long-defunct establishment as much as it is inertia. My background and upbringing are also reflected in my teaching—specifically, in the mnemonics I use and share with students.

Mnemonic devices are memory boosts—those rhymes, poems, slogans, or sketches that help people remember certain facts. The word derives from the Greek “Mneme” for memory and evokes Mnemosyne, the goddess of memory and mother of the muses. Supposedly, the literary use of mnemonics goes back 2,500 years, to Simonides the Younger, who promoted their use in the fifth century BC. Probably everyone has been exposed to mnemonics at some point in school, if only, perhaps, in elementary school spelling classes in order to learn that “I goes before E except after C or when sounding like (A) as in “neighbor” and (weigh).” Generations of schoolchildren are thus doomed to throw their

hands up in despair upon reading that “neither foreigners nor financiers forfeited their weird heights leisurely. ” They may also be driven to give up protein from heifers for good. But, because memory boosters must themselves be more memorable than the facts they're boosting, they are often most effective when they 're not just catchy rhymes but rather are customized to reflect the time and place of the rememberer.

One example from high school mathematics serves to illustrate this point. Trigonometry is the mathematical study of relationships among arcs and angles defined with respect to a circle; trigonometric functions allow the calculation of angles from known sides of angles and vice versa. If the circle is divided into quadrants, the trigonometric functions associated with triangles described with respect to the circle will be variously positive or negative, depending on the quadrant. In the first quadrant (equivalent to all angles between 12 and 3 on a clock face), all of the functions (sine, cosine, secant, and tangent) are positive. In the second quadrant (between 12 and 9), only the sine is positive; in the third quadrant (between 9 and 6), it's the tangent that's positive, and in the fourth quadrant (between 6 and 3), the cosine is positive.

In Williamsville High School, near Buffalo, New York, in 1970 it was important to remember these functions (although I must admit I can't remember why, other than to get a good grade on a trigonometry exam). The mnemonic device that our teacher shared with us was “ Albany State Teachers College”—All, Sine, Tangent, Cosine. This was a fairly effective mnemonic—I certainly remember it, 30 years later, although I've long had a sneaking suspicion that there never was a teachers college in Albany, New York.

But the point is that this mnemonic wouldn't have been particularly useful in West Virginia, where high school students couldn't be expected to have any connection to the state capital of New York. I don't know how schoolchildren in West Virginia remember the positive trigonometric functions. Some mnemonics texts suggest as an alternative “All Stations to Coventry,” which I expect is British in origin and must assume some familiarity with train schedules in the United Kingdom —again, not particularly helpful for students in West Virginia or anywhere else in the United States.

Biology is absolutely chockablock with mnemonic devices, at least in part because there is so much to memorize. In plant taxonomy we remembered the families of trees with opposite, rather than alternate, leaves by thinking of a MADCAP Horse—maple, ash, dogwood, Caprifoliaceae (honeysuckle), and horse chestnut. Human anatomy contributes many old classics—in the case of the spinal nerves, literally classic. My mother taught me a mnemonic for remembering the 12 spinal nerves —”On Old Olympus' Towering Tops/A Finn and German Viewed Some Hops,” for the olfactory, optic, oculomotor, trochlear, trigeminal, abducens, facial, acoustic, glossopharyngeal, vagus, spinal accessory, and hypoglossal nerves. Variants of course exist—one rude one asserts that the only individual viewing hops is a “Fat-Assed German” (Dr. Crypton, 1984).

Naughtiness seems to be rife among mnemonics—naughtiness is perhaps more memorable than, say, logic and good grammar. The more contemporary the mnemonic, the more likely it is to be if not obscene at least in bad taste. Many years ago, George Gamow developed a mnemonic for remembering the ten classes of stars, from hottest to coldest—“O, B, A, F, G, K, M, R, N, S” thus

became “Oh, Be A Fine Girl, Kiss Me Right Now, Sweetheart.” As mnemonics go, it's cute but hardly X-rated. By the time I got to college, things in the mnemonics world had heated up considerably. The teaching assistants I had in geology class were more than willing to provide us with a mnemonic for remembering the Moh scale of hardness—the progressive increase in hardness of minerals. The scale of ten included, in order, talc, gypsum, calcite, fluorite, apatite, orthoclase, quartz, topaz, corundum, and diamond. The mnemonic you typically see in books is “Texas girls can flirt and other queer types can do,” which grammatically doesn't make a lot of sense. This lack of grammatical correctness hasn 't diminished its popularity. It has been embellished, however; according to the version the teaching assistants taught us, the Texas girls were considerably friendlier and had moved well beyond flirting. For that matter, the embellishment seems entirely appropriate in a scale of hardness.

Perhaps it's not a general pattern—this accumulation I have of naughty mnemonics might simply reflect the fact that I went to school in the freshly liberated sixties and seventies. The mnemonic I share with undergraduates today for remembering the taxonomic hierarchy—Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, Species—is a case in point. There are many variants—among them, “Kings Play Chess on Fridays, Generally Speaking,” or “Kids Pour Coffee on Fat Girl Scouts,” or “King Philip Came Over From Glorious Scotland.” But the version I learned in mammalogy class in 1973, and the one I should probably stop teaching, is “King Philip Came Over From Germany, Stoned.” I don't know which King Philip it was and whether he was more likely to come over from Scotland clear-eyed and sober or from Germany with the munchies, but my students don't seem to care. In fact, they

usually get every question about taxonomic hierarchy correct on their exams.

I continued to acquire mnemonics throughout my undergraduate career, spanning the range from naughty to nice. There is a definite drawback to naughty mnemonics, though, in that they can be too memorable. I spent a summer in Fayetteville, Arkansas, in 1974 assisting in an ecological survey of Devil's Den State Park. As part of that survey, the team conducted a regular census of breeding birds, which we did by walking through a defined section of forest and recording and identifying bird calls—breeding birds defend their territories by singing and the number of calling males is a good indicator of the number of breeding pairs. We used the Field Guide to Birds of Eastern North America by Roger Tory Peterson to aid us in identifying the calls. For each bird species, the author provided a clever mnemonic phrase to aid in recognition—thus, the trill of a Carolina wren was rendered “Teakettle, teakettle, teakettle,” and the unique call of the ovenbird as “teacher, teacher, TEACHER!”

All this was fine until some members of the team thought it would be a good idea to substitute obscene equivalents of the mnemonic phrases. These quickly supplanted the quaint “pee-iks” and “quarks” of Peterson. These phrases were certainly easily remembered and instantly recognizable and greatly assisted us in completing the breeding bird census quickly and efficiently. But to this day, every time I walk through the woods when the birds are singing, I still have the unshakable feeling they 're actually screaming obscenities at me, and nature doesn't seem quite as peaceful and serene after you've been propositioned by a foul-mouthed scarlet tanager.

An o-pun and shut case

Ever since I acquired my first joke book (Arrow Book of Jokes and Riddles), I've had a peculiar affinity for puns. This particular comic bent was not shared by anyone in my immediate family, as I discovered every time I tried out a new one on whoever happened by. Nor was it shared by my orthodontist, Dr. Sidney Elfant. I was so nervous during my first visit to Dr. Elfant's office that I actually threw up in the chair, whereupon, in an effort to make me less apprehensive, Dr. Elfant hit upon the idea of asking me to come back next time with a joke to tell him. Being as compulsive then as I am now, I spent the next two weeks studying and analyzing jokes, trying to select an appropriate one and complete the task assigned. It seemed to have worked, since I didn't throw up during the second appointment, and it became a regular practice for me to come to each appointment with a joke. Unfortunately for Dr. Elfant, I had to wear braces for five years, so he had to endure quite a few jokes in the process. I couldn 't help noticing that whenever I told a joke that relied on a pun for the punch line, I always ended up with considerably more dental wicks in my mouth—making it much more difficult to relate any additional jokes during the rest of the appointment.

This interest in puns continued through high school. In fact, my Advanced Placement English teacher, Mr. Stein, chose a verse from Samuel Johnson with which to sign my yearbook:

“If I were punishéd

For every pun I shed,

There'd be no puny shed

Above my punnish head.”

In college, too, I was free to indulge in punning, but everything came to a grinding halt in graduate school. I learned quickly that puns and science are not universally regarded as logical partners. Professors ruthlessly and routinely rogued out any wordplay from term papers; editors rarely allowed one to get by. I think, in all of my 100+ published papers, I have succeeded in slipping only a single pun past an editor—it was a paper on furanocoumarin content of parsnip fruits and I thanked a colleague in the acknowledgments for “fruitful discussion.”

Admittedly, it wasn't even a masterful pun that I managed to get in print. Such do exist; one I'm particularly impressed with is in a paper by L.A. Fuiman and R.A. Batty in the Journal of Experimental Biology on the effects of temperature-induced changes in the viscosity of water on swimming performance of Atlantic herring. Appropriately enough, the paper is titled, “What a drag it is getting cold: partitioning the physical and physiological effects of temperature on fish swimming. ” The part preceding the colon is a sly reference to the first line of a Rolling Stones' song called “Mother's Little Helper.” I wonder whether it was Fuiman or Batty who thought of it, and I really wonder how they managed to

convince an editor to let it stand. A close second in punderstatement would be the paper by T. M. Blackburn, K. J. Gaston, R. M. Quinn, H.Arnold, and R. D. Gregory published in 1997 on the relationship between abundance and geographic size range in British mammals and birds, appropriately titled, “Of mice and wrens.” And there's the paper by L. Clayton, M. Keeling, and E. J. Milner-Gulland from 1997 presenting a spatial model of wild pig hunting in Sulawesi, Indonesia, titled “Bringing home the bacon.” I wish I could have found such accommodating editors for my efforts at scientific punning.

My experiences with editors (indeed, with just about everyone) lead me to wonder what is behind a sense of humor. Puns are almost universally despised—proponents are far outnumbered by detractors. The pun has been called “the lowest form of wit” by humorists (as the bun has been called the lowest form of wheat by bakers). In the eighteenth century, James Boswell felt that “a good pun may be admitted among the smaller excellencies of lively conversation,” but that sentiment isn't surprising considering he spent a lot of time with Samuel Johnson (see above). William Combe was less enthusiastic; in his view, a pun was “a paltry, humbug jest; those who have the least wit make them best.” By the nineteenth century, Oliver Wendell Holmes was declaring that “people that make puns are like wanton boys that put coppers on the railroad tracks. They amuse themselves and other children, but their little trick may upset a freight rain of conversation for the sake of a battered witticism.” And the opprobrium continues in the twentieth century. Fred Allen was reported to have said, “Hanging is too good for a man who makes puns; he should be drawn and quoted” and contemporary humorist Dave Barry

wrote, “Puns are little ‘plays on words' that a breed of person loves to spring on you and then look at you in a certain self-satisfied way to indicate that he thinks that you must think he is by far the cleverest person on Earth now that Benjamin Franklin is dead, when in fact what you are thinking is that if this person ever ends up in a lifeboat the other passengers will hurl him overboard by the end of the first day even if they have plenty of food and water” (Barry, 1988).

I can't help it—I still think they're funny. And a search of the biology literature fails to yield insights into why. It's not clear what the adaptive value of a sense of humor might be at all. Although early studies suggested that a sense of humor may mitigate stress, more carefully controlled follow-up studies failed to produce any evidence that a sense of humor moderates the impact of stress on physical illness (Porterfield, 1987). There are very few studies documenting a health-enhancing effect of humor. One study conducted by K. M. Dillon and colleagues in 1985 did document an increase in people's salivary immunoglobulin production after they viewed a humorous videotape. This may be suggestive of a beneficial effect; immunoglobulins help the body defend against infection. This finding also suggests a novel quantitative criterion for use in judging stand-up comedy competitions, although practical implementation (which would involve collecting spit from the audience and judges) may prove difficult.

This field of research presents daunting operational challenges in that there is no objective, quantitative way to measure someone' s sense of humor. Psychologists use instruments such as the Situational Humor Response Questionnaire, which asks subjects to indicate how much amusement they might derive from

common situations on a 5-point scale. This questionnaire thus is designed to measure “mirthfulness.” There are also humor appreciation tests that measure a subject's ability to detect the incongruity between joke stem and punchline and to evaluate the appropriateness of a punch line and a joke, as well as tests that ask subjects to rate individually a series of items that are designed to be either humorous or neutral.

Depite the obstacles, considerable progress is being made at determining the biological roots of humor appreciation. Shammi and Stuss (1999) conducted a study of 21 patients with focal damage in specific areas of their brains, using a series of humor appreciation tests and joke and story completion tests. For example, the patients were asked to read the setup of a joke and then select among a choice of punchlines. The investigators found that damage to the right frontal lobe had the most profound effect on the ability to appreciate humor. Although appreciation of slapstick was undiminished, the ability to pick out the clever line was muted. Thus, in one joke, a man asks his neighbor if he'll be mowing his lawn on Saturday; the neighbor answers “yes,” and what was generally regarded as the clever punch line was for the first man to respond, “Well, I guess you won't be needing your golf clubs.” Patients who had sustained damage to the right frontal lobe preferred the outcome in which, after the neighbor responds, “yes,” the first man steps on a rake.

The right frontal lobe is the region of the brain that integrates cognitive and affective information. Humor experts such as T. P. Millar argue that there are two elements of humor: bisociation, in which a joke leads from one associative plane to another, and affective loading, in which a tension is generated by the joke situation. Puns are almost entirely bisociation; affective tension is

minimal. That's okay by me. The idea that two silkworms had a race that ended in a tie is funny to me. So is the notion that a termite can walk up to a bar and ask, “Is the bartender here?” Maybe people who think puns are funny have affective deficits. Or maybe there are just genetic differences in intensity of activity in the different brain regions that govern these functions.

I like the idea that there may be a genetic basis for why I think puns are so funny. I actually did a literature search to see if there might be a pun gene. I found several references in a literature database. There is a pun gene in Drosophila melanogaster, reported by Fahmy and Fahmy in 1958, but pun is just an abbreviation for puny; the mutation affects eye morphology and wing length, not any tendency to resort to wordplay. This is unfortunate in that there is at least one well-known pun involving Drosophila melanogaster, according to which “time flies like an arrow but fruit flies like an apple.” The database turned up two other potential pun genes, but further investigation proved disappointing. Hammer et al. (1999), in FEMS Microbiology Letters, was about “the punABCD gene cluster from Pseudomonas fluorescens,” a bacterium; Gomi et al. (1994) in Neuroscience Letters was about “the Pun gene encoding PrP in titter rats.” Both of these references seemed suspect to me, although the one about titter rats clearly held a lot of promise. Fetching these references provided some unwelcome clarification. The paper by Hammer et al. (1999) was actually about the prnABCD gene complex (a pyrrolnitrin biosynthetic gene cluster) and Gomi et al. (1994) about Prn genes (prion protein genes) in zitter rats, not titter rats, zitter rats being a neurological mutant strain isolated in 1978 and characterized by tremulous motion, hind limb paresis, and pathological changes in the central nervous system. So both of these pun genes were

actually typographical errors. I find that very amusing—but, then, I would, wouldn't I? I only wish I could have found ten such typos, none of which represented a true gene for punning—then I could report with all seriousness that, after a search For such a gene controlling word play, no pun in ten did.

Hand-me-down genes

There are times when being a biologist affects the way you look at life. And why shouldn't it. Biology is, after all, the science of life and when something goes wrong with a life the majority of biologists experience at least a passing curiosity about the underlying mechanism responsible for the problem. Lots of things went wrong when my daughter, Hannah, was born, not in a really big way, but certainly in a big enough way to raise my curiosity as well as my maternal alarm. Among the biggest things to go wrong, she developed jaundice within a day of being born—but, then, so do about 50% of all full-term babies. Jaundice, characterized by a distinctive yellowish cast to the skin, is caused proximately by the inability of the liver to process the products of old, broken-down blood cells and excrete them properly. Hyperbilirubinemia refers to elevated levels of bilirubin, the principal breakdown product of hemoglobin, the oxygen-carrying pigment in red blood cells.

Usually, jaundice resolves itself without consequences but, in Hannah 's case, she was just as jaundiced at four days as she was at one day of age. The family doctor prescribed phototherapy—exposing the baby to broad spectrum white light to photoisomerize the bilirubin. Changing the structure of the bilirubin by

exposing it to light energy often renders it more water-soluble and hence excretable. After a day of phototherapy, Hannah's bilirubin levels had dropped to the point that we were allowed to take her home. But those levels remained higher than normal and we watched helplessly as the home health care nurse came at regular intervals to stick needles into her tiny foot and collect blood for monitoring. About a month after she came home, we were told that her bilirubin levels were unacceptably high; at this point, we didn't need to see lab test results, because, two weeks past Halloween, our daughter was still looking about as orange as a pumpkin.

Despite the intriguing aesthetic possibilities presented by an orange baby, we were extremely worried; accumulation of bilirubin in the brain can cause developmental delay, hearing loss, learning disorders, and perceptual motor handicaps. So we were more than anxious to bring her in for additional testing. Watching her being poked and prodded was absolute agony, but, underlying the agony was an insatiable need to know what was going on inside my daughter. My entomological training was basically useless here. With a few truly bizarre exceptions (such as the chironomid bloodworms that breed in sewage), insects don' t even have hemoglobin. They rely on a system of pipes and tubes for oxygen delivery, not an oxygen-carrying pigment. The tests were all uninformative, other than to indicate a problem with liver function. None of this was reassuring, and we were starting to get concerned about the long-term impact of the poking and prodding over and above the possible liver problem. One metabolic assay involved injecting Hannah with radioactive tracers and watching their progress through her system—leading my husband to speculate whether we might be able to change her

diapers at night for the next few days without turning the lights on. The only definitive bit of evidence was the result of a test conducted at the Mayo Clinic on a sample sent by the pediatric gastroenterologist who had taken over Hannah's care. This test revealed that Hannah was heterozygous for a mutant allele of alpha-1-antitrypsin.

Alpha-1-antitrypsin is a protein found in the blood. Its main function is to inhibit enzymes that break down other proteins, particularly leucocyte elastase from neutrophils (not trypsin, as the name “anti-trypsin ” might suggest). Neutrophil elastase is an enzyme that destroys bacteria and damaged cells in the lung; in the absence of adequate levels of AAT, elastase can proceed to destroy normal lung tissue as well. The normal protein is made up of a single chain of 394 amino acids, equipped with three large carbohydrate side chains. At least 90 variants of AAT have been described and the vast majority of these function normally. There are, however, a few mutations that affect function. People with these mutant variants experience alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency—that is, they do not produce sufficient blood levels of this protein. The major clinical manifestations of inadequate supplies of AAT are liver disease and early-onset emphysema. AAT is manufactured in liver cells; the mutant forms of the protein cannot exit the cells and in some cases accumulate and destroy the cells, leading to cirrhosis and hepatitis. Emphysema and other lung complications reflect the susceptibility of the alveoli in the lungs to destruction by elastase, the enzyme disarmed by AAT.

AAT deficiency is an autosomal recessive disease that is actually quite common among Caucasians of European descent; it has been estimated that a deficiency gene is found in as many as one in every 2,500 people in the United States. In Hannah's case, she

possessed one normal allele, designated M, and one mutant allele of the Z form. The mutant AATZ molecule differs from the normal molecule by only a single nucleotide base—so that the amino acid lysine is substituted for glutamate at position 342. Infants born who are homozygous for the Z allele—without a normal allele—often experience such profound liver damage that they need a transplant in early childhood. Heterozygotes—those with one normal allele—often live their whole lives without manifesting any symptoms.