Building Confidence in New Evidence Streams for Human Health Risk Assessment: Lessons Learned from Laboratory Mammalian Toxicity Tests (2023)

Chapter: Appendix C: Evidence Review: Approach, Methods, and Results

Appendix C

Evidence Review: Approach, Methods, and Results

This appendix describes the approach and methods that the committee used to address aspects of its charge relevant to the review of the existing literature that evaluated evidence on variability and concordance of laboratory mammalian toxicity tests. The primary literature reporting on outcomes in relevant laboratory mammalian toxicity tests and amenable to de novo review and analysis was voluminous, and a formal systematic review of this literature was not considered within scope of the committee’s effort. However, the committee considered literature consisting of reviews, wherein information from multiple relevant studies, experiments, or databases was compiled and analyzed.

The committee’s approach comprised two aspects. The first was to review existing systematic reviews relevant to the committee’s charge. Systematic reviews provide a transparent, comprehensive, and consistent evaluation of available data with less bias than other types of reviews and analyses and have been used or recommended by National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) for assessment of environmental health evidence in multiple reports (NASEM 2017, 2019, 2022; NRC, 2014a,b). To identify and evaluate systematic reviews of the scientific evidence of the highest methodological quality relevant to the committee’s charge, the committee conducted an overview review. The overview approach used by the committee has been defined and used in clinical medicine (Pollock et al., 2019) and evaluation of systematic reviews has been applied in three prior NASEM reports evaluating evidence in environmental health, including the recent NASEM study on per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), as well as other reports sponsored by the EPA and the Department of Defense (NASEM, 2019, 2021, 2022). Overall, this approach is consistent with the goal specified in the committee’s charge for a “comprehensive, workable, objective, and transparent process.” Further, systematic reviews have been adopted by various federal agencies, including the EPA’s Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS)program [Office of Research and Development (ORD)Staff Handbook for Developing IRIS Assessments, 2022] and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS)’s Division of Translational Toxicology (DTT) Integrative Health Assessments Branch (IHAB) method, and Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA)requires systematic reviews for evaluating the weight of evidence of hazard (EPA, 2021). Accordingly, the committee’s findings can be readily adapted as they rely on evidence of the highest methodological quality to support decision-making in environmental health by federal entities.

The second aspect of the committee’s approach entailed compilation and evaluation of the published reviews and analyses of data on variability of mammalian toxicity tests that were identified during the open sessions of the committee, including the two public workshops. This literature was reviewed for relevance to the statement of task by two independent screeners using prespecified inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the included articles were evaluated for methodological quality (particularly concerning selective inclusion of data and consideration of risk of bias).

The following sections summarize the methods and results of these two approaches.

OVERVIEW REVIEW OF SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS

The committee developed a prespecified method that included the following:

- Definition of relevant terms

- Scoping questions

- Two objectives and associated PECO statements and inclusion/exclusion criteria

- Keywords

- Search methods

- Approach for data collection, screening, and assessment of methodological quality

- Approach for analysis and presentation of results.

The approach is detailed subsequently. Following is the file history for these methods:

- Developed September 30, 2021

- Modifications (10/11/2022):

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria (see items marked with *)

- Adopted approach to follow-up on AMSTAR 2 tool questions (see item marked with **)

INTRODUCTION TO THE APPROACH

The goal of the literature review is to provide information and findings that can support the committee’s charge to identify existing literature that can be used to inform the committee’s answers to the charge questions. The literature review will be, as noted in the charge, “comprehensive, workable, objective, and transparent.” The primary literature reporting on outcomes in relevant laboratory mammalian toxicity tests and amenable to de novo review and analysis was extensive and broad, and a formal systematic review of this literature was not considered within scope of the committee’s effort. However, the committee considered the available literature on this topic that consisted of reviews, wherein information from multiple experiments or databases was compiled and analyzed. To support the committee’s work to answer the charge questions, the literature review goals are to identify reviews of the existing literature of high methodological quality that can be used to answer the charge questions. NASEM, in multiple reports, recommends systematic reviews to evaluate the environmental health scientific literature for hazard and risk assessment as they produce a transparent, comprehensive and consistent evaluation with less bias evaluation of the science (NASEM, 2017, 2019, 2022; NRC, 2014a,b). Further, systematic reviews have been adopted by federal agencies, including IRIS and NIEHS via their DTT IHAB method, and TSCA requires systematic reviews for evaluating the weight of evidence of hazard (EPA, 2022). Thus, the committee’s approach is to first identify and evaluate systematic reviews that are relevant to the charge questions.

Reviews of reviews have grown as systematic reviews have been established within clinical medicine. Cochrane has a method called Overviews, but other terms have been used, including Umbrella Reviews, “reviews of reviews,” and “meta-reviews” (Pollock et al., 2019). The committee will use the Overview approach but adapted to address their purposes. Overviews include an objective, selection criteria, a comprehensive search for systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses, assessment of the methodological quality/risk of bias, data collection, analysis, and certainty of evidence. The steps up to and including the risk of bias evaluation will be most informative to the committee’s effort.

Previous NASEM reports have used published tools to evaluate the potential for bias of reviews using both ROBIS and AMSTAR 2 (A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews) (Shea et al., 2017; Whiting et al., 2016). The committee will apply the AMSTAR 2 tool that has been used to evaluate systematic reviews in environmental health in previous NASEM reports (NASEM, 2019, 2021, 2022).

DEFINITIONS

For this report and our evaluation of NAMs the committee defined the following: concordance of adverse health effects, biological variability, experimental variability, internal validity, and external validity (see also Box 2-2). The committee based its definitions on those developed by previous authoritative bodies, including the NASEM, EPA, and Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). There were some cases where there was not a complete existing definition of definitions that were conflicting or overlapping. Thus, the committee updated our definitions to provide clarity on the different aspects of evaluating the science related to NAMs and its comparison to other lines of evidence.

Concordance of adverse health effects describes a similarity in responses to chemical exposures across different animal species. Concordance does not require exact mimicry and can involve a continuum of interrelated biological responses that may act through different or multiple mechanisms, pathways, and organ systems. Adverse health effects in experimental animals and humans can differ from one another in presentation and still be concordant due to a range of reasons including variations that may occur in exposure conditions (e.g., timing and duration of exposure and toxicokinetic differences) and tissue sensitivity (e.g., toxicodynamic differences).

Adverse health outcome: A biochemical change, functional impairment, or pathological lesion that affects the performance of the whole organism, or reduces an organism’s ability to respond to an additional environmental challenge (EPA IRIS definition).

Note that this is consistent with other adverse health definitions, such as provided in California Law for hazard trait regulation (Title 22, Cal Code of Regs, Div 4.5, Chapter 54; alternatively 22 CCR 69401 et seq.): (a) “Adverse effect” for toxicological hazard traits and endpoints means a biochemical change, functional impairment, or pathologic lesion that negatively affects the performance of the whole organism, or reduces an organism’s ability to respond to an additional environmental challenge. “Adverse effect” for environmental hazard traits and endpoints means a change that negatively affects an ecosystem, community, assemblage, population, species, or individual level of biological organization.

Biological variability is defined as the true differences in attributes due to heterogeneity or diversity. Therefore, variability is usually not reducible but can be better characterized or controlled via rigorous experimental design. With respect to animal studies, this would include differences in responses between animals of different species, strain, age, sex, body weight, history, and concurrent or previous exposures. For humans this would correspond to differences in outcomes across the population due to differences in intrinsic factors (e.g., life stage, reproductive status, age, gender, genetic traits) and acquired factors (e.g., previous or ongoing exposure to multiple chemicals, pre-existing disease, geography, socioeconomic status, racism/discrimination, cultural, workplace).

Experimental variability such as inter-laboratory variability (differences or lack thereof in results between laboratories performing the exact same experiment under the same conditions), intra-laboratory variability (differences or lack thereof in results in the same laboratory performing the exact same experiment under the same conditions but with different operators), or repeatability (differences or lack thereof in results from the same experiment conducted twice) are considered under reproducibility within the context of the present work. By comparison, for humans this

would correspond to differences in test results due to technical differences from one assay to another or one laboratory to another.

Internal validity relates to the extent to which systematic error (bias) can influence how a study answers its research question (from the EPA IRIS Handbook and the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews).

External validity refers to whether the study is asking the relevant research question and the extent to which results from a study can be applied (generalized) to other situations, groups, or contexts.

SCOPING QUESTIONS

The committee reviewed the EPA charge questions and divided them into a series of scoping questions that form the basis of the overview review. The relationship between the charge questions from the EPA and the scoping questions identified by the committee are covered in Table C-2. The committee used the Cochrane Handbook domains for defining the scoping question for the overview, which includes clear description of the populations, exposures, comparators, outcome measures, time periods, and settings.

For overviews that examine different interventions for the same condition or population, the primary objective of the overview may be stated in the following form: “To summarize systematic reviews that assess the effects of [interventions or comparisons] for [health problem] for/in [types of people, disease or problem, and setting].” They can be used to summarize evidence from systematic reviews “about adverse effects of an intervention for one or more conditions or populations.” Accordingly, the committee can use environmental exposures in place of intervention for this purpose and the objective of the overview in environmental health to “summarize systematic reviews that assess the effects of [environmental exposures] for [health problem] for/in [types of people, disease or problem, and setting].” In this application the committee also includes authoritative reviews in addition to systematic reviews. The committee uses the same approach as for a Cochrane Overview and defines our objective, selection criteria, search, inclusion, assessment of methodological quality/risk of bias, data collection, analysis, and certainty of evidence. The overall approach will include the following steps: a literature search, screening of abstracts, a full text review of studies identified in the abstract screening, and the evaluation of a final set of relevant studies.

SELECTION CRITERIA

The committee will only include systematic reviews with or without meta-analysis and authoritative reviews. The committee defines authoritative reviews as reviews produced by governmental agencies and international agencies (i.e., U.S. EPA, U.S. National Toxicology Program (NTP,) U.S. state agencies, foreign governmental agencies, European Union (EU), International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) World Health Organization (WHO)). The specifics of selection criteria by scoping question are given in detail under each scoping question.

Objectives, PECO Statements, and Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Objective 1: To summarize the systematic reviews and authoritative reviews that assess the concordance of adverse health effects between laboratory mammalian models and humans following exposures to environmental agents

- Populations: laboratory mammalian models, humans.

- Exposures: Exposures to environmental agents (chemicals, pollutants, and pharmaceuticals). Exposures can be of any duration and during any life stage. *Added radiation and natural chemicals to the list, does not include biological exposures such as pathogens or biological therapies.

- Comparators: Comparison of higher exposures to lower exposures. Lower exposures can include controls.

- Time periods: Will include all ranges of timing of exposure.

- Outcomes: Comparison of similar adverse health effects. Similar adverse health effects will be based on the preceding definition and include systemic apical endpoints (e.g., observable endpoints such as cancer, birth defects, and organ level effects), and biological responses (e.g., influences DNA/epigenome, oxidative stress, hormone responses, inflammation, immunosuppression, receptor mediation). *Added can be a positive or negative health effect, studies that evaluate safety can be used to identify changes or adverse responses.

Inclusion Criteria

- Include peer reviewed papers that are a systematic review. Include authoritative reviews.

- Paper must include both animal (mammalian) and human exposures to environmental or pharmaceutical agents, *including radiation and alcohol, and outcomes/measures.

- Include studies of any exposure duration, route, or life stage. Include if animal (mammalian) and human exposure routes or durations differ, or if the route, timing, or duration exposure is not described.

- Include papers that compare outcomes between mammalian laboratory animals and humans, outcomes should fit within the given concordance definition—similarity in biological responses but does not require exact mimicry and can involve a continuum of interrelated biological responses that may act through different or multiple mechanisms, pathways, and organ systems. *Can be a positive or negative health effect, studies that evaluate safety can be used to identify changes or adverse responses.

Exclusion Criteria

- Exclude nonsystematic reviews and *Meta-analysis only reviews.

- Exclude studies that are only based on human data, only based on nonhuman mammalian data, or only on nonmammalian data.

- Exclude studies that do not have similar exposures in human and nonhuman mammalian studies.

- *Exclude studies that evaluate biological exposures such as pathogens or viruses.

- Exclude studies that do not compare outcomes between mammalian model animals and humans.

Keywords

- Concordance

- Adverse effect

- Biological response

- Toxicity testing

- Safety testing

- Mammal

- Human

- Rat

- Mouse

- Rodent

- Guinea pig

- Dog

- Primate

- Monkey

- Environmental chemical

- Environmental agent

- Toxic

- Hazardous

- Pollutant

- Pharmaceutical

- Drug

- Xenobiotic

Objective 2: To summarize the systematic reviews and authoritative reviews that assess variability of laboratory mammalian studies following exposures

- Populations: laboratory mammalian models.

- Exposures: Exposures to environmental chemicals, pollutants, pharmaceuticals. Exposures can be of any duration and during any life stage.

- Comparators: Comparison of higher exposures to lower exposures. Lower exposures includes controls. Exposures can include internal measures of exposure and exposures that are given by any route (e.g., dermal, oral, inhalation).

- Time periods: Include all timing of exposures.

- Outcomes: Adverse health effects. Adverse health effects are defined above and will include systemic apical endpoints (e.g., pathology, cancer, birth defects), biological responses (e.g., hormone responses, mutagenicity, inflammation markers, immunological markers and other key characteristics as needed).

Inclusion Criteria

- Include peer reviewed papers that are a systematic review. Include authoritative reviews.

- Include systematic reviews comparing results from mammalian model experiments.

- Include studies that evaluate exposures to environmental or pharmaceutical agents, of any exposure duration or route or during any life stage.

- Include studies that compare higher to lower exposures, including controls.

- Include studies that evaluate any adverse health outcomes (as defined previously) and include observable systemic apical endpoints (e.g., pathology, cancer, birth defects), biological responses (e.g., hormone responses, mutagenicity, inflammation markers, immunological markers, and other key characteristics as needed).

Exclusion Criteria

- Exclude nonsystematic reviews.

- Exclude studies that are only based on human data or nonmammalian data. Exclude field/wildlife studies.

- Exclude studies that do not evaluate exposures to environmental or pharmaceutical agents.

- Exclude studies that do not compare higher to lower exposures, including controls.

- Exclude studies that do not evaluate adverse health effects.

Search Methods

Relevant Index Terms

| MEDLINE (PubMed) | Embase |

|---|---|

| Toxicity Tests | Toxicity Testing |

| Pre-Clinical Drug Evaluation | Drug Screening |

| Drug | |

| Environmental Pollutants | Environmental Chemical |

| Environmental Exposure | Pollutant |

| Animal Experimentation | Animal Experiment |

| Animals | |

| Mouse | Mice |

| Experimental Mouse | |

| Rats | Rat |

| Experimental Rat | |

| Dogs | Dog |

| Experimental Dog | |

| Swine, Miniature | Minipig |

| Experimental Guinea Pig | |

| Primates | Multiple – see search strings |

The following terms and combinations were employed. Bold and Italic results were exported to EndNote.

MEDLINE

| # | Query | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | exp Toxicity Tests/ OR exp Drug Evaluation, Preclinical/ OR (Toxicity-Test* OR preclinical-drug-evaluation OR drug-evaluation,-preclinical OR drug-evaluation-studies,-preclinical OR drug-evaluations,-preclinical OR drug-screening OR drug-screenings OR evaluation,-preclinical-drug OR evaluation-studies,-drug,-pre-clinical OR evaluation-studies,-drug,-preclinical OR evaluations,-preclinical drug OR medicinal-plants-testing,-preclinical OR preclinical-drug-evaluation OR preclinical-drug-evaluations OR screening,-drug OR screenings,-drug).ti,ab | 400,004 |

| 2 | exp Mice/ or exp Rats/ or exp Guinea Pigs/ or exp Dogs/ or exp Swine, Miniature/ or exp Primates/ | 2,309,138 |

| 3 | Exp Environmental Pollutants/ OR exp Environmental Exposure/ | 537,271 |

| 4 | 1 and 2 | 300,812 |

| 5 | Limit 4 to (animals and (meta-analysis or “systematic review”)) | 266 |

| 8 | Limit 4 to (humans and (meta-analysis or “systematic review”)) | 659 |

| 9 | exp Animal Experimentation/ | 10,148 |

| 10 | 2 and 3 | 280,404 |

| 11 | 3 and 9 | 234 |

| 12 | 10 or 11 | 280,476 |

| # | Query | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 13 | Limit 12 to (meta-analysis or “systematic review”) | 3,205 |

| 14 | exp Drug Evaluation, Preclinical/ OR (preclinical-drug-evaluation OR drug-evaluation,-preclinical OR drug-evaluation-studies,-preclinical OR drug-evaluations,-preclinical OR drug-screening OR drug-screenings OR evaluation,preclinical-drug OR evaluation-studies,-drug,-pre-clinical OR evaluation-studies,-drug,-preclinical OR evaluations,-preclinical drug OR medicinal-plants-testing,-preclinical OR preclinical-drug-evaluation OR preclinical-drug-evaluations OR screening,-drug OR screenings,-drug).ti,ab | 289,315 |

| 15 | 2 and 14 | 220,557 |

| 16 | 3 and 14 | 1,362 |

| 17 | 15 or 16 | 221,046 |

| 18 | Limit 17 to (meta-analysis or “systematic review”) | 543 |

| 19 | exp Animals/ | 25433432 |

| 20 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 9 or 14 | 23,637,993 |

| 21 | (systematic adj 2 review).ti,ab | 232,774 |

| 22 | (umbrella adj2 review).ti,ab | 880 |

| 23 | Review of reviews.ti,ab | 723 |

| 24 | (scoping adj2 review).ti,ab | 13,763 |

| 25 | (over review or overreview).ti,ab | 13 |

| 26 | (meta-analyses or metaanalyses or meta-analysis or metaanalysis).ti,ab | 227,473 |

| 27 | 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 | 364,650 |

| 28 | 19 or 27 | 295,673 |

| 29 | 20 and 27 | 295,113 |

| 30 | 28 or 29 | 298,237 |

| 31 | Concordance.ti,ab. | 53,408 |

| 32 | 30 and 31 | 757 |

Embase

| # | Query | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | exp Toxicity Testing/ OR (acute toxicity tests OR chronic toxicity tests OR skin irritancy tests OR subacute toxicity tests OR subchronic toxicity tests OR toxicity test).ti,ab | 52,084 |

| 2 | Exp drug screening/ OR (antitumor drug screening assays OR antitumour drug screening assays OR drug evaluation OR drug scanning OR drug testing OR drug trial OR pharmaceutical screening OR xenograft model antitumor assays OR xenograft model antitumour assays).ti,ab | 169,435 |

| 3 | Exp mouse/ OR exp rat/ OR exp dog/ OR exp guinea pig/ OR exp minipig/ OR exp ape/ OR exp chimpanzee/ OR exp orangutan/ OR exp halporhini/ or exp pan paniscus/ OR exp gorilla/ OR exp hominid/ OR (mice OR mouse OR rat OR rats OR Cavia OR ginea pig OR guinapig OR dog OR Canis canis OR Canis domesticus OR Canis familiaris OR Canis lupus familiaris OR micro pig OR micropig OR micropigs OR mini pig OR minipig OR mini swine OR miniswine OR miniature pig OR miniature swine OR minipigs OR miniswine OR apes OR hominoid OR Hominoidea OR Haplorrhini OR haplorhini OR monkey OR chimpanzee OR pan paniscus OR gorilla OR orangutan OR hominid OR bonobo).ti,ab | 26,014,544 |

| # | Query | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 4 | Exp environmental chemical/ OR exp pollutant/ OR exp drug/ OR (chemical micropollutant OR environment pollutant OR environmental pollutants OR pollutant agent OR radioactive pollutants OR acid drug OR basic drug OR biopharmaceutic agent OR drugs OR medicament OR pharmaceutical preparations OR pharmaceutical substance OR pharmacochemic OR pharmacochemical agent OR pharmacon OR synthetic drug OR synthetic drugs).ti,ab | 4,610,417 |

| 5 | 1 or 2 | 219,012 |

| 6 | 3 and 4 and 5 | 79,440 |

| 7 | Limit 6 to (animals and (meta-analysis or “systematic review”)) | 15 |

| 8 | Limit 6 to (meta-analysis or “systematic review”) | 464 |

| 9 | Limit 6 to (humans and (meta-analysis or “systematic review”)) | 449 |

| 10 | 4 and 5 | 124,670 |

| 11 | Limit 10 to (meta-analysis or “systematic review”) | 507 |

| 12 | Exp experimental mouse/ OR exp experimental rat/ OR exp experimental guinea pig/ OR exp experimental dog/ OR (“experimental mouse” OR “experimental rat” OR “experimental guinea pig” OR “experimental dog” OR “Bama miniature pig” OR “Gottingen minipig” OR “Ossabaw miniature pig” OR “Wuzhishan miniature pig” OR “Yucatan micropig”).ti,ab | 705,049 |

| 13 | Exp simian/ OR exp Catarrhini/ OR exp Cercopithecidae/ OR exp Cercopithecinae/ OR exp Cercocebus/ OR exp Chlorocebus/ OR exp Erythrocebus/ OR exp Lophocebus/ OR exp macaca/ OR exp rhesus monkey/ OR exp Mandrillus/ OR exp Colobinae/ OR exp Colobus/ OR exp Platyrrhini/ OR exp chimpanzee/ OR exp gorilla/ OR exp orangutan/ OR exp hylobatidae/ OR (simian OR old world monkey* OR new world monkey* OR baboon OR macaca or rhesus monkey OR Mandrillus OR Theropithicus OR Colobin* OR colobus OR chimpanzee or bonobo or gorilla OR gibbon).ti,ab | 23,009,179 |

| 14 | 12 or 13 | 23,536, 451 |

| 15 | Exp animal experiment/ | 2,678,768 |

| 16 | 1 or 2 or 15 | 2,842,719 |

| 17 | 4 and 14 | 2,389,774 |

| 18 | 4 and 15 | 728,895 |

| 19 | 4 and 14 and 15 | 221,464 |

| 20 | 14 and 16 | 795,985 |

| 21 | 4 and 14 and 16 | 263,294 |

| 22 | Limit 17 to (animal studies and (meta-analysis or “systematic review”)) | 420 |

| 23 | Limit 17 to ((meta-analysis or “systematic review”) and (ape or dog or guinea pig or monkey or mouse or rat or swine) | 602 |

| 24 | Limit 18 to Limit 6 to (animal studies and (meta-analysis or “systematic review”)) | 429 |

| 25 | Limit 18 to ((meta-analysis or “systematic review”) and (ape or dog or guinea pig or monkey or mouse or rat or swine) | 300 |

| 26 | Limit 19 to Limit 6 to (animal studies and (meta-analysis or “systematic review”)) | 302 |

| 27 | Limit 19 to ((meta-analysis or “systematic review”) and (ape or dog or guinea pig or monkey or mouse or rat or swine) | 211 |

| 28 | Limit 20 to (animal studies and (meta-analysis or “systematic review”)) | 955 |

| 29 | Limit 20 to ((meta-analysis or “systematic review”) and (ape or dog or guinea pig or monkey or mouse or rat or swine) | 599 |

| # | Query | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 30 | Limit 21 to (animal studies and (meta-analysis or “systematic review”)) | 308 |

| 31 | Limit 21 to ((meta-analysis or “systematic review”) and (ape or dog or guinea pig or monkey or mouse or rat or swine) | 223 |

| 32 | 22 – 31 (joined with OR operators) | 1,733 |

| 33 | 3 or 12 or 13 | 177,777 |

| 34 | 16 and 33 | 64,747 |

| 35 | Limit 34 to (meta-analysis or “systematic review”) | 86 |

| 36 | 2 and 3 and 4 | 66,394 |

| 37 | Limit 36 to (animal studies and (meta-analysis or “systematic review”) | 18 |

| 38 | Limit 36 to (animals and (meta-analysis or “systematic review”) | 10 |

| 39 | Limited 36 to (meta-analysis or “systematic review”) | 407 |

| 40 | 2 or 15 | 2,820,651 |

| 41 | 14 and 40 | 789,092 |

| 42 | 4 and 14 and 40 | 259,597 |

| 43 | Limit 41 to (animal studies and (meta-analysis or “systematic review”) | 960 |

| 44 | Limit 41 to (animals and (meta-analysis or “systematic review”) | 73 |

| 45 | Limited 36 to (meta-analysis or “systematic review”) | 2,866 |

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

| # | Query | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Toxicology.mp | 53 |

| 2 | mice OR mouse OR rat OR rats OR Cavia OR ginea pig OR guinapig OR guinea pig OR dog OR Canis canis OR Canis domesticus OR Canis familiaris OR Canis lupus familiaris OR micro pig OR micropig OR micropigs OR mini pig OR minipig OR mini swine OR miniswine OR miniature pig OR miniature swine OR minipigs OR miniswine OR apes OR hominoid OR Hominoidea OR Haplorrhini OR haplorhini OR monkey OR chimpanzee OR pan paniscus OR gorilla OR orangutan OR hominid OR bonobo | 759 |

| 3 | Pollutant* or “environmental chemical”.mp | 44 |

| 4 | Drug* or pharmaceutical*.mp | 8,168 |

| 5 | 1 and 2 and 4 | 8 |

| 6 | 1 and 2 and 3 | 1 |

Authoritative Reviews

In addition to searching the academic literature, keyword searches were performed on the URLs for specific government and international agency websites, including the EPA, IARC, and EU. These searches included terms such as “review of,” “systematic review,” “meta-analyses/-sis” and synonyms.

Data Collection, Screening, and Assessment of Methodological Quality

- Compilation of articles from the literature search

- Title/abstract screening (in duplicate) for inclusion/exclusion per PECO (Population (including animal species), Exposure, Comparator, and Outcomes) using PICOPortal (https://picoportal.net/)

- Full text review (in duplicate) of included studies per PECO (some additional exclusions anticipated)

- Critical appraisal of methodologic quality/risk of bias using the AMSTAR 2 (A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews) tool

- Accounting of identified studies, those excluded during abstract and full-text review

Certainty of Evidence

For the evaluation of each of the systematic reviews, an overall judgment will be reached based on the critical elements evaluated (see text description of the AMSTAR 2 approach below).

Description of AMSTAR Tool for Evaluating Systematic Reviews

The committee will evaluate studies using AMSTAR 2 (Shea et al., 2017), adapting it for evaluating environmental health systematic reviews using the same approach as was used to evaluate systematic reviews for PFAS by NASEM (2022) and several other NASEM committees (2019, 2021).

AMSTAR-2 includes 16 domains. The committee will follow the NASEM PFAS committee (2022) and recommendation by Shea to focus on seven critical appraisal domains for rating the overall confidence in the systematic review (see Box C-1). Each systematic review will be evaluated with the AMSTAR 2 tool by a staff member and confirmed by a committee member. The overall confidence in each systematic review was evaluated using the AMSTAR 2 tool with the guidance given in Table C-1.

** For AMSTAR Item 7, if all other critical domains are rated as sufficient, and this item is rated as No, study authors will be contacted to determine whether they can provide justification for excluding studies or a list of excluded literature.

Data Extraction

Information about the included studies will be extracted including population, interventions, and outcomes covered in addition to the methodological quality. Specifically, the information will include

- Reference: Author, year, and DOI number if relevant

- Population: Species

- Exposure: Descriptive information on the dose or exposure level, timing, and route for the environmental chemicals, pharmaceutical intervention, or other exposure (e.g., radiation) studied

- Outcome measures: Characterization of the adverse health effect comprising apical and other relevant biological responses

- Risk of bias: Information on relevant domains as well as overall judgments.

TABLE C-1 Rating Overall Confidence in the Results of the Review

| Rating and Definition | Explanation/Notes |

|---|---|

| High | |

| No or one noncritical weakness: the systematic review provides an accurate and comprehensive summary of the results of the available studies that address the question of interest | Cannot have a critical weakness in any of the seven critical domains (Box C-1), and at most one weakness in the other nine domains |

| Moderate | |

| More than one noncritical weaknessa: the systematic review has more than one weakness but no critical flaws. It may provide an accurate summary of the results of the available studies that were included in the review | Cannot have a critical weakness in any of the seven critical domains (Box C-1) |

| Low | |

| One critical flaw with or without noncritical weaknesses: the review has a critical flaw and may not provide an accurate and comprehensive summary of the available studies that address the question of interest | Can have one critical weakness in one of the seven critical domains (Box C-1), and can also have weaknesses in the other nine domains |

| Critically low | |

| More than one critical flaw with or without noncritical weaknesses: the review has more than one critical flaw and should not be relied on to provide an accurate and comprehensive summary of the available studies | Has more than one critical weakness in the seven critical domains and can also have weaknesses in the other nine domains. |

a Multiple noncritical weaknesses may diminish confidence in the review, and it may be appropriate to move the overall appraisal down from moderate to low confidence.

| Charge Question | Question Based on Charge Question Related to Literature Review | Components of the Review | Scoping Question: This Will Form the Basis of the Literature Review |

|---|---|---|---|

| Charge question 3: What do the literature review and workshops indicate about concordance between laboratory mammalian models and humans in the adverse effects following chemical exposure and how might this frame expectations of NAMs when they cannot be compared directly with human studies? | What does the literature review indicate about concordance between laboratory mammalian models and humans in the adverse effects following chemical exposure? | Review the scientific literature on the overall concordance between laboratory mammalian models and humans in the adverse effects following exposure to commercial, environmental, and pharmaceutical chemicals, and other agents (e.g., radiation) where available. | Draft scoping question 1: What do systematic reviews conclude about indicators of concordance between laboratory mammalian models and humans for biological response/adverse effects following exposure to environmental agents? |

| Charge question 2: Given the results of the literature review and workshops, what are the implications of the qualitative and quantitative variability of laboratory mammalian toxicity studies when using them to establish the performance of NAMs? | What does the literature review indicate about qualitative and quantitative variability of laboratory mammalian toxicity studies when using them to establish the performance of NAMs? | Review the scientific literature pertaining to the qualitative and quantitative variability in laboratory mammalian toxicity tests. | Scoping Question 2: What do systematic reviews conclude about variability in laboratory mammalian studies? |

Outputs

Data tables, figures, and/or visualizations in Tableau will reflect the extent of coverage and quality of the included studies. If adopted, the data visualizations will contain descriptive information and be flexible to allow the user to organize the studies by population, interventions, and outcomes and assess the study quality.

Analyses

The committee will review the reported findings relevant to their charge questions to inform their conclusions, focusing on the studies of higher quality.

Results

Overall, 72 studies met the inclusion criteria for the variability and/or concordance questions and were evaluated using the AMSTAR-2 tool. An information request was sent to the study authors (via an initial request and a follow-up 2 weeks later) if justification for excluding studies or a list of excluded literature was not provided in the publication or supplemental material, and this domain was a key determinant of the overall judgment. The ratings were updated according to the response.

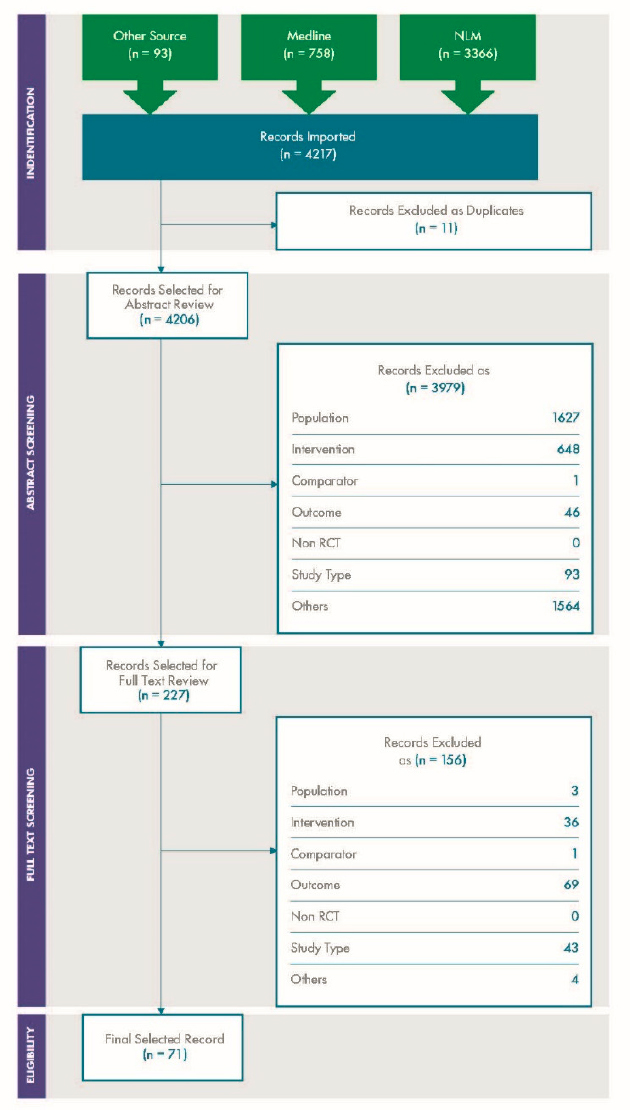

For variability, a total of 4,206 articles were screened, of which 227 were selected for full text review. A further 156 were excluded at the full text stage, and 71 were included in the review. The results are depicted in the PRISMA diagram shown in Figure C-1.

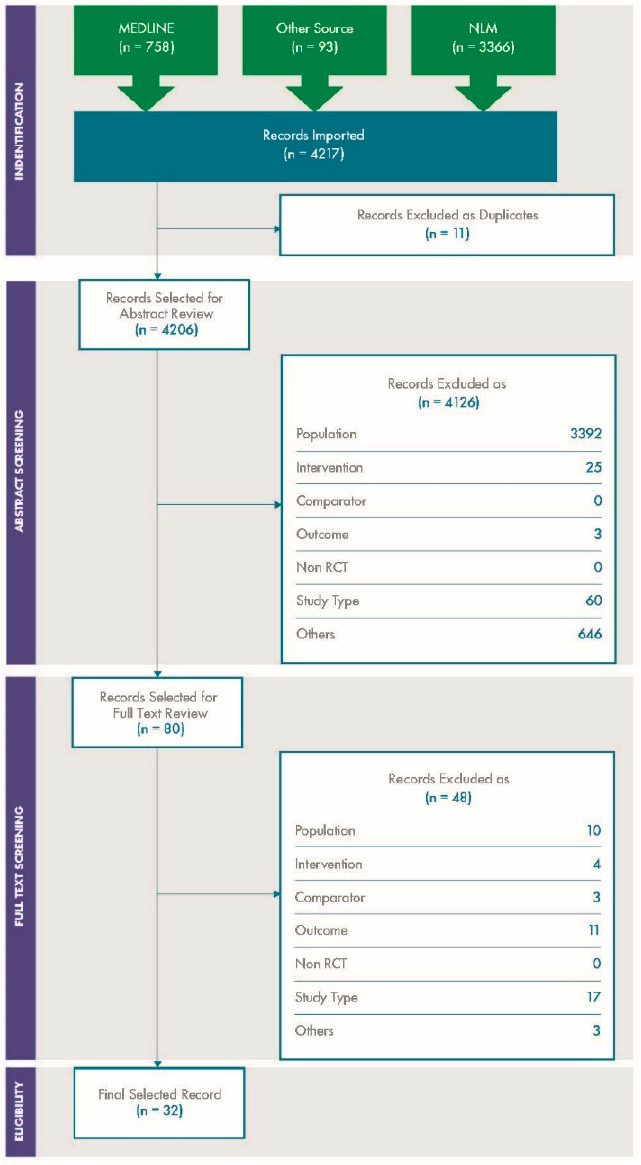

For concordance, a total of 4,206 articles were screened, of which 80 were selected for full text review. A further 47 were excluded at the full text stage, and 32 were included in the review. The results are depicted in the PRISMA diagram in Figure C-2.

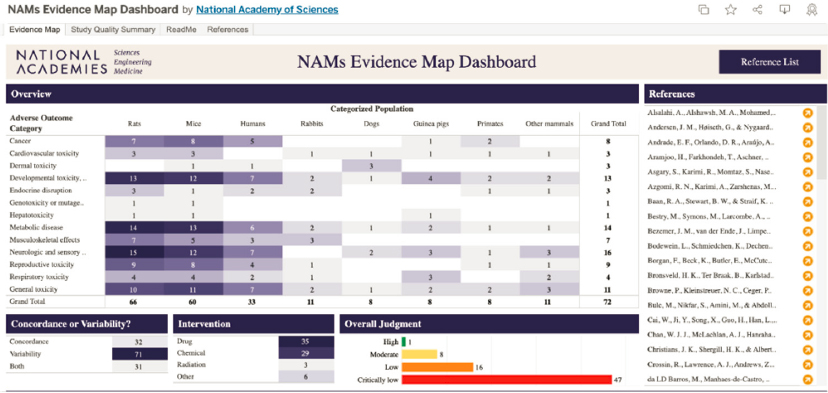

Systematic reviews judged to be of critically low quality were not considered further by the committee. Figure C-3 provides an overview of the populations (species), interventions (drug, chemical, radiation), and adverse outcomes covered by the remaining 25 studies included in the committee’s review. Further information, including the detailed evaluation criteria, can be accessed for these studies via the evidence map dashboard.1

Of the 25 studies of higher methodological quality (i.e., with an overall judgment of low, moderate, or high), 6 are described in the text of Chapters 3 and 4 (Andersen et al., 2020; Soliman et al., 2021; the two systematic reviews in the 2017 NASEM report [NASEM, 2017]; Perel et al., 2007; Ramsteijn et al., 2020), and the remaining 19 studies are detailed subsequently.

Andrade et al. (2019) examined the effects resveratrol has on alveolar bone loss and an expression of cytokines in rats and mice. The strengths of the study were the excluded study justification, consideration of risk of bias in the reviewed studies, meta-analysis methodology, and results interpretation. The a priori methodology and search strategy were considered adequate. They examined seven mammalian preclinical studies and reported a high level of heterogeneity between the studies (I2 = 95%; p < 0.01).

Bestry et al. (2022) investigated the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on DNA methylation in humans, primates, rats, and mice. The strengths of the study were the a priori methodology and the consideration of risk of bias in the reviewed studies in interpreting results. The search strategy and risk-of-bias approach were considered adequate. No meta-analysis was performed. The authors did not provide an analysis of variability (qualitative or quantitative) across multiple laboratory mammalian toxicity studies. Overall, there was inadequate evidence to support an association between prenatal alcohol exposure and altered DNA methylation because of heterogeneity in study design and methods.

Bezemer et al. (2021) evaluated the general safety and efficacy of allamines in humans and in mice. The strengths of the study were the a priori methodology, the comprehensive search strategy, the justification for exclusions, the risk-of-bias approach, and the interpretation of results. The publication did not provide an analysis of variability (qualitative or quantitative) across multiple laboratory mammalian toxicity studies. The authors noted the large heterogeneity in study designs, investigated systems, and endpoints. A meta-analysis could not be performed because the identified studies were few in number, heterogeneous, and of low quality.

Bodewein et al. (2019) evaluated the general toxicological effects of electromagnetic fields in humans and various experimental animals (rats, mice, guinea pigs, and dogs). The strengths of the study were the comprehensive search strategy, the justification for exclusions, the risk-of-bias approach, and the interpretation of results. Overall, the evidence examined was inadequate to reach conclusions due to heterogeneity of study designs, methods, and endpoints.

A report from the European Commission, Directorate-General for Environment (Joas et al., 2018) presented results of a study on endocrine-disrupting activity or effects, including those manifested at later life stages, in humans and laboratory or environmental animals (including rodents and rabbits). The strengths of the study included a comprehensive search strategy, the risk-of-bias methodology, and the interpretation of results. The a priori methods were considered adequate.

___________________

1 See https://public.tableau.com/app/profile/leslie.beauchamp/viz/NAMsEvidenceMapDashboard/EvidenceMap?publish=yes.

The publication does not provide an analysis of variability (qualitative or quantitative) across multiple laboratory mammalian toxicity studies. The report focused on temporal aspects of animal test guidelines for endocrine disruption and found many gaps and limitations in design that compromised concordance.

Jukema et al. (2021) examined the potential benefits and deleterious effects of antileukotrienes administered to prevent or treat chronic lung disease in very pre-term newborn mammals. The populations included humans, mice, rats, guinea pigs, rabbits, and other mammals with effects reported within 10 days of birth. The publication did not provide an analysis of variability (qualitative or quantitative) across multiple laboratory mammalian toxicity studies. Overall, there was inadequate evidence to support the use of antileukotriences to prevent lung disease in very preterm newborns due to heterogeneity in study designs, methods, and high level of bias.

Leenaars et al. (2019) is a scoping review to identify studies that evaluate concordance through examination of translational success and failure rates. The strengths of the study were the a priori methods, a comprehensive search strategy and interpretation of results based on risk of bias analysis. All but one of the included studies were of very low quality. The authors were contacted in order to identify the higher quality studies, which were not listed in the article, but they did not respond after several attempts. The authors noted that “the data presented in this paper have severe limitations. They should be considered inconclusive and used for hypothesis-generation only.” An analysis of variability (qualitative or quantitative) across multiple laboratory mammalian toxicity studies was not included. The concerns about the quality of the included studies raised concerns that this study alone cannot be used to evaluate concordance.

Leffa et al. (2019) considered the neurologic and sensory system effects of methylphenidate in the spontaneously hypertensive rat (SHR) model of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The strengths of the study were the consideration of risk of bias for reviewed studies, the methodology for the meta-analysis review, the final interpretation of the results, and finally the publication bias approach. The a priori methodology, search strategy, and excluded study justification were considered adequate. The study considered different outcomes of ADHD including hyperactivity, attention, impulsivity, and memory using a variety of outcome measures that were grouped by the authors. They identified 36 studies that met the inclusion criteria. The authors noted significant heterogeneity in hyperactivity outcome measures with a I2 = 70% and a Chi2 = 151.56 (df = 45, p < 0.001) and similarly significant heterogeneity in attention analysis with an I2 = 68% and a Chi2 = 72.68 (df = 23, p < 0.001). The impulsivity analysis showed low heterogeneity with I2 = 9% and a Chi2 = 8.8 (df = 8, p = 0.36), while the memory analysis showed moderate heterogeneity with an I2 = 43% and a Chi2 = 22.97. They discuss differences in study design but do not comment on the sources of outcome heterogeneity.

Morahan et al. (2020) reviewed the effects of a nonnutritive sweetener diet during pre-gestation, gestation, and/or lactation in rat and mouse models. The strengths of the study include the a priori methodology, the extensive search strategy, the justification of excluded studies, the consideration of risk of bias in reviewed studies, the methodology utilized for the meta-analysis, and the interpretation of the results. The consideration of publication bias was deficient. The study found low variability for effects on maternal weight (I2 12%) and litter size (0%), but not for offspring weight at weaning (80%) or in adulthood (92%).

Rogers et al. (2016) analyzed the relationship between low energy sweetener consumption and body weight in humans, primates, rabbits, and rats. The strengths of the study were the comprehensive search, the meta-analysis methods, and the consideration of publication bias. Risk of bias was assessed for human but not animal studies. Overall, the results were heterogeneous, with studies in humans showing no overall association with body weight. Of 49 experiments reporting the effects of forced low energy sweeteners on body weight, 5 reported a gain, 21 reported a loss, and 23 reported no effect. Median group size was 12, 20, and 18, respectively (mean group size 10, 171, 54), suggesting those studies reporting weight gain may have been underpowered.

Shojaei-Zarghani et al. (2020) evaluated dietary natural methylxanthines and colorectal cancer through examination of caffeinated beverages and chocolate in humans and caffeine administration in mice and rats. The strengths of the study include the a priori methods, the comprehensive search strategy, the methods for examining risk of bias and conducting the meta-analysis. Of five studies of incidence, two showed an increase, two showed a decrease, and one showed no change. In three studies of the effects on existing tumors, one showed increased tumor burden, one showed a reduction, and one showed no change. Of two studies of effects on mortality, one showed an increase, and one showed a decrease. Of note, two studies did not report group size, and median group size for those which did was 9. Overall, there was inadequate evidence to support a role for caffeine (methylxanthines) and colorectal cancer in humans as was observed in rodents due to inability to reliably determine both exposure and dose of caffeine (methylxanthine) in epidemiologic studies. Subgroup analysis that found an association lacked adjustment for known covariates, such as smoking, and had a high risk of bias.

Sophocleous et al. (2022) examined the effects of synthetic and natural cannabinoid receptor ligands on skeletal remodeling (bone mineral density in humans, and bone cell activity and bone volume in mice, rats, and rabbits). The strengths of the study were the justification for excluded studies, the meta-analysis methods, and the interpretation of results although the methods were not established a priori. Overall, there were inconsistencies between results in animal models and in humans, but conclusions were limited because the studies were few in number and heterogeneous.

Wikoff et al. (2021) evaluated exposure to dioxin-like compounds and reduced sperm count in humans and rats. The strengths of the study were the methods for evaluating risk of bias and conducting the meta-analysis as well as the interpretation of the results. The a priori methods and search strategy were considered adequate, but any impact of publication bias was not considered. The publication also did not fulfill some other noncritical domains including providing a satisfactory explanation for, and discussion of, any heterogeneity observed in the results of the review; and reporting on the sources of funding for the studies included in the review. Finally, study funding was provided by Dow Chemical, which represents a financial conflict of interest per risk-of-bias domains. One limitation of this systematic review is that the researchers only evaluated rat studies and did not include studies of other mammals. Although they noted there were studies in mice and hamsters, no method or data were reported to demonstrate a systematic search and evaluation of mouse and hamster studies. Thus, it was difficult to evaluate concordance for these other species. Regarding variability, they reported a high level of heterogeneity (I2 > 84%) across models and approaches and noted that qualitative exploratory sensitivity analyses indicated that there were no obvious patterns in dose-response relationship based on strain or postnatal age at evaluation,

suggesting the underlying data are themselves inconsistent. The figures support a general concordance of effect based on similar decreases in sperm count in the human and animal studies. Overall, the systematic review could be subject to bias and was of insufficient rigor overall to draw conclusions.

Zhang et al. (2022) examined the effects of bisphenol A on oxidative stress in rats and mice. The strengths of the study were the a priori methods, the methods for assessing risk of bias and conducting the meta-analysis, and the interpretation of the results. The search strategy was considered adequate. The authors identified 20 publications with a median sample size of 7. The majority of studies were of unclear risk of bias over most of the 10 Syrcle risk of bias indicators. Across 7 indicators of oxidative damage, I2 was 57% for glutathione reductase and greater than 90% for the remaining indicators. Some of this heterogeneity could be explained by aspects of study design including dose, duration of exposure, and the tissue in which antioxidant effects were sampled.

Although meeting the inclusion criteria for the variability review, five publications did not provide an analysis of variability (qualitative or quantitative) across multiple laboratory mammalian toxicity studies informative of the committee’s charge. These publications were not among the studies included for concordance review. In brief, these studies addressed the following:

- Da L. D. Barros et al. (2018) focused on the effects of fluoxetine on neonatal inhibition of serotonin reuptake in rats and mice.

- Hooijmans et al. (2016) analyzed the effects of anesthetic drugs on metastasis in laboratory mice and rats with experimental cancer.

- Kinkade et al. (2021) examined the effects of metformin in rat and mice studies on experimental myocardial infarction.

- Michelogiannakis et al. (2018) analyzed the effect of nicotine on orthodontic tooth movement in rodent models.

- Zhao et al. (2021) analyzed antitumor activities of Grifola frondosa (Maitake) polysaccharide in mice.

REVIEW OF PUBLICATIONS PRESENTED TO THE COMMITTEE

The committee developed a prespecified method to review publications presented to them during open sessions with the sponsor or during the two public workshops. This method included the following:

- Definition of relevant terms

- PECO statements and inclusion/exclusion criteria

- Approach for data collection, screening, and assessment of methodological quality

- Approach for evaluation of internal validity

- Analysis and presentation of results.

The approach is detailed as follows.

Introduction

The goal of the supplemental literature review is to assemble material presented to the committee during the workshops and by the EPA to inform the committee’s answers to the charge questions regarding variability and concordance. Specifically, the objective is as follows: to compile and assess studies presented to the committee by the EPA or at the workshops that assess variability or concordance of outcomes in laboratory mammalian studies following exposures to environmental agents (drugs, chemicals, radiation).

Definitions

This supplemental literature review will rely on the same definitions of terms provided in the overview review (see previous discussion) for the following concepts: concordance, adverse health outcomes, biological variability, experimental variability, reproducibility, internal validity, and external validity.

PECO and Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

The following PECO statement will be employed:

- Populations: laboratory mammalian models and/or humans.

- Exposures: Exposures to environmental chemicals, pollutants, pharmaceuticals. Exposures can be of any duration and during any life stage.

- Comparators: Comparison of higher exposures to lower exposures. Lower exposures include controls. Exposures can include internal measures of exposure and exposures that are given by any route (e.g., dermal, oral, inhalation).

- Outcomes: Adverse health effects, including systemic apical endpoints (e.g., pathology, cancer, birth defects), and biological responses (e.g., hormone responses, mutagenicity, inflammation markers, immunological markers and other key characteristics as needed).

Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria are as follows:

- Include reviews and studies identified in presentations to the committee by the EPA or during the workshops.

- Include studies that evaluate exposures to environmental or pharmaceutical agents, of any exposure duration or route or during any life stage.

- Include studies that compare higher to lower exposures, including controls.

- Include studies that evaluate any adverse health outcomes (observable systemic apical endpoints such as pathology, cancer, birth defects, and biological responses such as hormone responses, mutagenicity, inflammation markers, immunological markers and other key characteristics as needed).

- Include studies that evaluated more than one experiment.

Exclusion Criteria

- Exclude studies that are only based on human data or nonmammalian data.

- Exclude field/wildlife studies.

- Exclude studies that do not evaluate exposures to environmental or pharmaceutical agents.

- Exclude studies that do not compare higher to lower exposures, including controls.

- Exclude studies that do not report adverse health effects as outcomes.

- Exclude studies that report results of individual experiments.

- Exclude studies or reviews that are not part of EPA or workshop presentations.

Data Collection, Screening, and Assessment of Methodological Quality

- Compilation of published articles made available to the committee through workshops, and EPA presentations to the committee.

- Title/abstract screening (in duplicate) for inclusion/exclusion per population, exposure, comparator, and outcomes (PECO) using https://picoportal.org/.

- Full text review (in duplicate) of included studies per PECO (some additional exclusions anticipated).

- Critical appraisal of methodologic quality/risk of bias using a modification of the NIEHS DTT IHAB (OHAT tool) (for primary literature) or elements of the AMSTAR 2 tool (for reviews).

- Accounting of identified studies, those excluded during abstract and full-text review.

Evaluation of Internal Validity

The NIEHS DTT IHAB method (https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/ntp/ohat/pubs/riskofbiastool_508.pdf), with a question on funding bias, will be used for primary literature (i.e., presents primary data). The AMSTAR 2 tool will be used for reviews and meta-analyses (i.e., that summarizes data). An overall tiering of individual studies will be reached based on the critical elements evaluated.

Data Extraction

Information about the included studies will be extracted including population, interventions, and outcomes covered in addition to the ROB analysis. Specifically, the information will include:

- Reference: Author, year, and DOI number if relevant.

- Population: Species, sex, life stage, and strain.

- Exposure: Descriptive information on the dose or exposure level, timing, and route for the environmental chemicals, pharmaceutical intervention, or other exposure (e.g., radiation) studied.

- Outcome measures: Characterization of the adverse health effect comprising apical and other relevant biological responses.

- Risk of bias: Information relevant for judging risk of bias, including source of funding.

Outputs

Data tables, figures, and/or evidence maps in Tableau will reflect the extent of coverage and quality of the included studies. If adopted, the evidence maps will contain descriptive information and be flexible to allow the user to organize the studies by population, interventions, and outcomes and assess the study quality.

Analyses

The committee will review the reported findings on variability and concordance to inform their conclusions, focusing on the studies of higher quality.

RESULTS

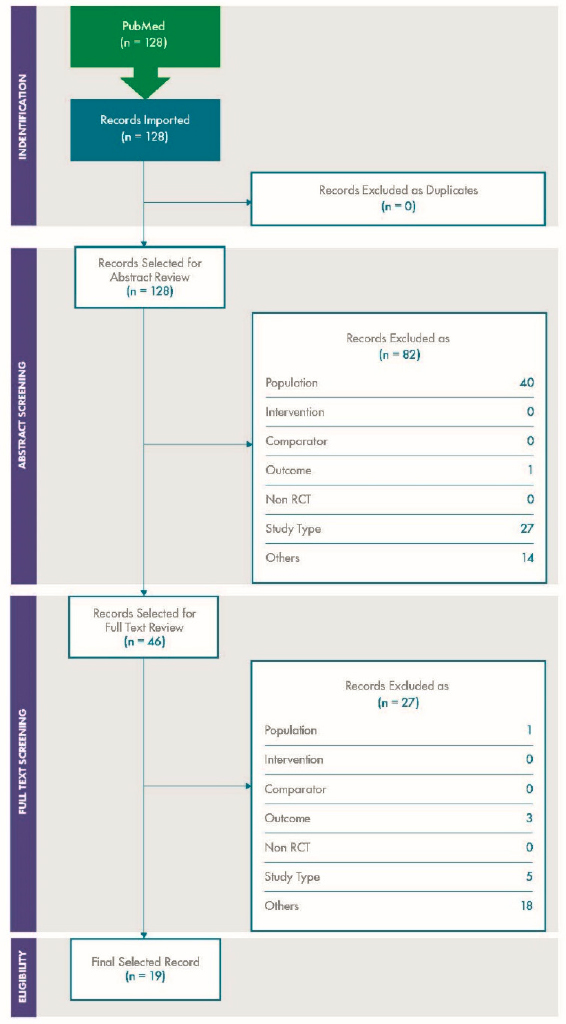

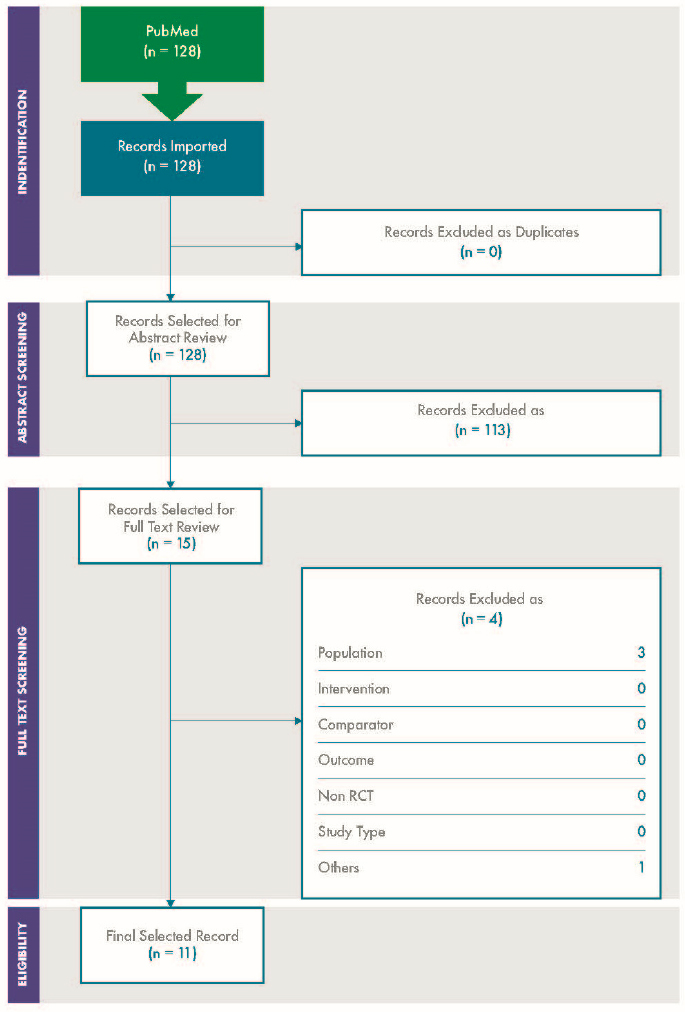

Figure C-4 and Figure C-5 show the PRISMA diagrams for the supplemental literature review on variability and concordance, respectively.

Two of the studies included for both variability and concordance, Baan et al. and the NASEM 2017b report, were considered as part of the “overview review” described previously; details regarding these studies are available in the Tableau dashboard. The remaining studies on variability and concordance are further detailed in Table 3-3 and Table 4-2, respectively.

REFERENCES

Andersen, J. M., G. Høiseth, and E. Nygaard. 2020. “Prenatal Exposure to Methadone or Buprenorphine and Long-Term Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis.” Early Human Development 143 (April): 104997.

Andrade, E. F., D. R. Orlando, A. M. S. Araújo, Jnbm de Andrade, D. V. Azzi, R. R. de Lima, A. R. Lobo-Júnior, and L. J. Pereira. 2019. “Can Resveratrol Treatment Control the Progression of Induced Periodontal Disease? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Preclinical Studies.” Nutrients 11(5). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11050953.

Bestry, M., M. Symons, A. Larcombe, E. Muggli, J. M. Craig, D. Hutchinson, J. Halliday, and D. Martino. 2022. “Association of Prenatal Alcohol Exposure with Offspring DNA Methylation in Mammals: A Systematic Review of the Evidence.” Clinical Epigenetics 14(1): 12.

Bezemer, J. M., J. van der Ende, J. Limpens, H. J. C. de Vries, and H. D. F. H. Schallig. 2021. “Safety and Efficacy of Allylamines in the Treatment of Cutaneous and Mucocutaneous Leishmaniasis: A Systematic Review.” PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource] 16(4). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249628.

Bodewein, L., K. Schmiedchen, D. Dechent, D. Stunder, D. Graefrath, L. Winter, T. Kraus, and S. Driessen. 2019. “Systematic Review on the Biological Effects of Electric, Magnetic and Electromagnetic Fields in the Intermediate Frequency Range (300 Hz to 1 MHz).” Environmental Research 171 (April): 247–259.

Da L. D. Barros, M., R. Manhaes-de-Castro, D. T. Alves, O. G. Quevedo, A. E. Toscano, A. Bonnin, and L. Galindo. 2018. “Long Term Effects of Neonatal Exposure to Fluoxetine on Energy Balance: A Systematic Review of Experimental Studies.” European Journal of Pharmacology 833 (August): 298–306.

European Commission. 2018. “Temporal aspects in the testing of chemicals for endocrine disrupting effects (in relation to human health and the environment): Final Report.” Publications Office, 2018, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2779/789059

EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). 2021. “Draft Systematic Review Protocol Supporting TSCA Risk Evaluations for Chemical Substances Version 1.0” https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2021-12/draft-systematic-review-protocol-supporting-tsca-risk-evaluations-for-chemical-substances_0.pdf.

Hooijmans, C. R., F. J. Geessink, M. Ritskes-Hoitinga, and G. J. Scheffer. 2016. “A Systematic Review of the Modifying Effect of Anaesthetic Drugs on Metastasis in Animal Models for Cancer.” PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource] 11 (5). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0156152.

Jukema, M., F. Borys, G. Sibrecht, K. J. Jørgensen, and M. Bruschettini. 2021. “Antileukotrienes for the Prevention and Treatment of Chronic Lung Disease in Very Preterm Newborns: A Systematic Review.” Respiratory Research 22(1): 208.

Kinkade, C. W., Z. Rivera-Núñez, L. Gorcyzca, L. M. Aleksunes, and E. S. Barrett. 2021. “Impact of Fusarium-Derived Mycoestrogens on Female Reproduction: A Systematic Review.” Toxins 13(6). https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins13060373.

Leenaars, C. H. C., C. Kouwenaar, F. R. Stafleu, A. Bleich, M. Ritskes-Hoitinga, R. B. M. De Vries, and F. L. B. Meijboom. 2019. “Animal to Human Translation: A Systematic Scoping Review of Reported Concordance Rates.” Journal of Translational Medicine 17(1): 223.

Leffa, D. T., A. C. Panzenhagen, A. A. Salvi, C. H. D. Bau, G. N. Pires, I. L. S. Torres, L. A. Rohde, D. L. Rovaris, and E. H. Grevet. 2019. “Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Behavioral Effects of Methylphenidate in the Spontaneously Hypertensive Rat Model of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder.” Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 100 (May): 166–179.

Michelogiannakis, D., P. E. Rossouw, D. Al-Shammery, Z. Akram, J. Khan, G. E. Romanos, and F. Javed. 2018. “Influence of Nicotine on Orthodontic Tooth Movement: A Systematic Review of Experimental Studies in Rats.” Archives of Oral Biology 93 (September): 66–73.

Morahan, H. L., C. H. C. Leenaars, R. A. Boakes, and K. B. Rooney. 2020. “Metabolic and Behavioural Effects of Prenatal Exposure to Non-Nutritive Sweeteners: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Rodent Models.” Physiology & Behavior 213 (January): 112696.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2017. Application of Systematic Review Methods in an Overall Strategy for Evaluating Low-Dose Toxicity from Endocrine Active Chemicals. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/24758.

NASEM. 2019. Review of DOD’s Approach to Deriving an Occupational Exposure Level for Trichloroethylene. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25610.

NASEM. 2021. The Use of Systematic Review in EPA’s Toxic Substances Control Act Risk Evaluations. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25952.

NASEM. 2022. Guidance on PFAS Exposure, Testing, and Clinical Follow-Up. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26156.

NRC (National Research Council). 2014a. Review of the Environmental Protection Agency’s State-of-the-Science Evaluation of Nonmonotonic Dose-Response Relationships as They Apply to Endocrine Disruptors. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/18608.

NRC. 2014b. Review of EPA’s Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) Process. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/18764.

Perel, P., I. Roberts, E. Sena, P. Wheble, C. Briscoe, P. Sandercock, M. Macleod, L. E. Mignini, P. Jayaram, and K. S. Khan. 2007. “Comparison of Treatment Effects between Animal Experiments and Clinical Trials: Systematic Review.” BMJ 334(7): 197.

Pollock, M., R. M. Fernandes, L. A. Becker, and D. Pieper. 2019. “V: Overviews of Reviews.” In J. P. T. Higgins, J. Thomas, J. Chandler, M. Cumpston, T. Li, M. J. Page, and V. A. Welch (Eds), Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Analysis of Interventions. Cochrane, 2022. http://training.cochrane.org/handbook.

Ramsteijn, A. S., L. Van de Wijer, J. Rando, J. van Luijk, J. R. Homberg, and J. D. A. Olivier. 2020. “Perinatal Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Exposure and Behavioral Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses of Animal Studies.” Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 114 (July): 53–69.

Rogers, P. J., P. S. Hogenkamp, C. de Graaf, S. Higgs, A. Lluch, A. R. Ness, C. Penfold, et al. 2016. “Does Low-Energy Sweetener Consumption Affect Energy Intake and Body Weight? A Systematic Review, Including Meta-Analyses, of the Evidence from Human and Animal Studies.” International Journal of Obesity 40 (3): 381–394.

Shea, B. J., B. C. Reeves, G. Wells, M. Thuku, C. Hamel, J. Moran, D. Moher, et al. 2017. “AMSTAR 2: A Critical Appraisal Tool for Systematic Reviews That Include Randomised or Non-Randomised Studies of Healthcare Interventions, or Both.” BMJ 358 (September): j4008.

Shojaei-Zarghani, S., A. Yari Khosroushahi, M. Rafraf, M. Asghari-Jafarabadi, and S. Azami-Aghdash. 2020. “Dietary Natural Methylxanthines and Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Food & Function 11(1): 10290–10305.

Soliman, N., S. Haroutounian, A. G. Hohmann, E. Krane, J. Liao, M. Macleod, D. Segelcke, et al. 2021. “Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cannabinoids, Cannabis-Based Medicines, and Endocannabinoid System Modulators Tested for Antinociceptive Effects in Animal

Models of Injury-Related or Pathological Persistent Pain.” Pain 162 (S). https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002269.

Sophocleous, A., M. Yiallourides, F. Zeng, P. Pantelas, E. Stylianou, B. Li, G. Carrasco, and A. I. Idris. 2022. “Association of Cannabinoid Receptor Modulation with Normal and Abnormal Skeletal Remodelling: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of in Vitro, in Vivo and Human Studies.” Pharmacological Research: The Official Journal of the Italian Pharmacological Society 175 (January): 105928.

Whiting, P., J. Savović, J. P. Higgins, D. M. Caldwell, B. C. Reeves, B. Shea, P. Davies, J. Kleijnen, and R. Churchill. 2016. “ROBIS: A New Tool to Assess Risk of Bias in Systematic Reviews Was Developed.” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 69, 225-234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.06.005.

Wikoff, D. S., J. D. Urban, C. Ring, J. Britt, S. Fitch, R. Budinsky, and L. C. Haws. 2021. “Development of a Range of Plausible Noncancer Toxicity Values for 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-P-Dioxin Based on Effects on Sperm Count: Application of Systematic Review Methods and Quantitative Integration of Dose Response Using Meta-Regression.” Toxicological Sciences: An Official Journal of the Society of Toxicology 179(2): 162–182.

Zhang, H., Yang, R., Shi, W., Zhou, X., and Sun, S. 2022. The Association between Bisphenol A Exposure and Oxidative Damage in Rats/Mice: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Environmental Pollution 292, 118444.

Zhao, F., Z. Guo, Z. R. Ma, L. L. Ma, and J. Zhao. 2021. “Antitumor Activities of Grifola Frondosa (Maitake) Polysaccharide: A Meta-Analysis Based on Preclinical Evidence and Quality Assessment.” Journal of Ethnopharmacology 280 (November): 114395.