Building Confidence in New Evidence Streams for Human Health Risk Assessment: Lessons Learned from Laboratory Mammalian Toxicity Tests (2023)

Chapter: 2 Background and Definitions

2

Background and Definitions

BACKGROUND ON THE USE OF LABORATORY MAMMALIAN TOXICITY TESTS IN HUMAN HEALTH RISK ASSESSMENT

The 2007 report Toxicity Testing in the 21st Century: A Vision and a Strategy provided a historical perspective of regulatory toxicology (NRC, 2007). As part of the historical background on the use of laboratory animal tests in human health risk assessment, the 2007 report provides an overview on how current toxicity-testing strategies evolved, why differences arose among and within federal agencies, and who contributed to the process. This report will not resummarize these points but, rather, build upon them.

There is a long history of animal use as models for toxicity testing (Parasuraman, 2011). The use of animals in toxicity studies began in the 1920s to determine the 50% lethal dose (LD50) of a chemical. Rabbit models for eye and skin irritation were later introduced by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Subsequently, the U.S. National Cancer Institute developed a test to identify carcinogenic potential of chemicals through repeat dosing to rats and mice. Starting in the 1980s, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) began publishing harmonized guidelines for toxicity testing of chemicals. Chemicals in scope of Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Title 21 (drugs) and CFR Title 40 (pesticides) require a specific battery of animal-based toxicity tests so regulators can determine the chemical’s risk to human health prior to its market authorization. In such cases, data from multiple toxicity studies that are compliant with good laboratory practices (GLP) and that often follow OECD or similar test guideline methods are needed for registration of these chemicals. However, for chemicals that are not within scope of these specific regulations, such as chemicals registered under the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) and other commodity chemicals and environmental pollutants, the hazard and risk assessment is instead based on the available evidence, which can comprise in vitro, in vivo laboratory mammalian, and human epidemiological data. However, in practice, these assessments have usually been based largely on guideline laboratory mammalian studies.

Thus, although differences exist between different global regulatory requirements, the current risk assessment approach is built around a common paradigm based on the underlying premise that, in the absence of evidence to the contrary, undesirable effects observed in mammalian studies are adequately predictive of potential undesirable effects in humans (Clark and Steger-Hartmann, 2018; Knight et al., 2021; Monticello et al., 2017; Olson et al., 2000). In general, the mammalian testing paradigm has provided a strong foundation for hazard and risk assessment; however, there are limitations to animal studies such as differences in toxicokinetics and toxicodynamics, which can result in differences in concordance or sensitivity between human and animal results. At their inception, laboratory mammalian toxicity studies were the best available option as there were no other toxicity tests technologically feasible, and effects in animals were reasonably anticipated to be relevant to humans. Over the decades of use, some laboratory mammalian toxicity tests have evolved based on scientific evidence in order to better protect human health, and test guidelines were developed. However, technological progress and scientific advances have opened new doors. In addition, due to the limited resources and requirements for animal testing, the pace of testing has not kept up with the regulatory need, nor has the diversity of endpoints required to fully characterize toxic response been achieved using only guideline studies.

Achieving the 21st Century Toxicity Testing Vision described in the 2007 report would entail substantially less reliance on animal testing and a shift in focus from adverse apical endpoints to mechanistic processes and other biomarkers of homeostatic perturbations. Subsequent National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) reports (NASEM, 2017; NRC, 2009) noted the importance of advancing the science and regulatory acceptance of this vision so that decision-making can be based on such “upstream” effects, and of using data from a wider variety of testing systems, such as the use of fish and alternative animal models, including alternative mammalian models.

In addition, there are continuing national and international interests and legislative mandates to develop alternative test methods that fulfill the “3 Rs”: replace animal use, reduce the number of animals required for a test procedure, and where animals are still required, refine testing procedures to lessen or eliminate unrelieved pain and distress.

Workshop 1: Observations on Use of Laboratory Animal Tests in Human Health Risk Assessment

The background on the use of mammalian toxicity tests in human health risk assessment was also discussed in Workshop 1 (see Box 2-1 for additional details). Several observations made by participants parallel those discussed previously, in particular:

- From the point of view of most regulatory toxicologists, risk assessors, and decision-makers, mammalian laboratory animal studies provide actionable evidence in terms of human health risk assessment and risk management decision-making.

- In some cases, existing evidence evaluation and decision-making frameworks statutorily require the use of “intact animals” to identify a hazard.

- Limitations of mammalian laboratory animal studies have been identified, and efforts have been made to address some of them through a combination of approaches, such as physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling, use of uncertainty or safety factors, changes to study designs, and use of mechanistic data.

- The types of endpoints used for risk assessment should continue to evolve away from only those that signify severe and frank effects (i.e., signs of toxicity) to perturbations that indicate disruption of biological systems and functions (i.e., upstream markers of disease risk).

The next section will expand further on this last point regarding the growing desire to provide greater human health protection through identification of perturbations that indicate disruption of biological systems and processes, in particular by reviewing findings from previous NASEM reports on the future of toxicity testing.

BACKGROUND ON THE FUTURE OF TOXICITY TESTING

Toxicity Testing in the 21st Century: A Vision and a Strategy (NASEM 2007)

In 2004, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) asked the National Research Council (NRC) to conduct a comprehensive review of the established and emerging toxicity testing approaches, leading to the formation of the Committee on Toxicity Testing and Assessment of Environmental Agents. This committee produced two reports, the first being a review of existing toxicity testing strategies titled Toxicity Testing for Assessment of Environmental Agents: Interim

Report (NRC, 2006). This report reviewed the current state of toxicity testing and identified the tensions created by the different objectives of regulatory toxicity testing, namely (1) depth of information for hazard identification and dose-response assessment; (2) breadth in coverage of chemicals, end points, and life stages; (3) animal welfare protection by minimizing animal suffering and using the fewest possible animals; and (4) conservation of money and time spent on testing and regulatory review. The second committee report, Toxicity Testing in the 21st Century: A Vision and a Strategy (NRC, 2007), developed a long-range vision and strategy for toxicity testing with the goal of addressing the tensions of depth, breadth, animal welfare, and conservation.

Toxicity Testing in the 21st Century: A Vision and a Strategy envisioned a transformative change in which routine toxicity testing would be conducted in human cells, human tissue surrogates, or human cell lines in vitro by evaluating cellular responses in a suite of toxicity pathway assays (NRC, 2007). This new approach to toxicity testing is presumed to greatly increase human relevance, significantly reduce the cost and time required to conduct chemical safety assessments, and markedly reduce and potentially eliminate high-dose animal testing. This proposed transformation in the toxicity testing of chemicals was intended to move the science of risk assessment away from reliance on high-dose animal studies to assess the likelihood of effects at relevant environmental exposures of human populations.

Science and Decisions: Advancing Risk Assessment (NRC, 2009)

In response to a request from the EPA to improve risk assessment approaches for environmental chemicals, the 2009 report Science and Decisions: Advancing Risk Assessment focused on two broad elements: improving the technical analysis supporting risk assessment (more accurate characterizations of risk) and improving the utility of risk assessment (more relevant to risk management decisions). While most of this report provided important recommended upgrades to how science is used in hazard and risk assessment more generally, there are several topics that are also relevant to the future of toxicity testing.

First, Science and Decisions: Advancing Risk Assessment recommends more explicit consideration of human variability that is biologically based, including heterogeneity due to age, sex, and health status in addition to genetics. Since this report was published, numerous experimental models both in vivo and in vitro based on heterogeneous populations, rather than homogeneous test systems, have been developed that have potential to quantify human variability (Rusyn et al., 2022). This issue of characterizing variability has implications for how experimental animal study variability is interpreted, and thus how the committee addresses charge question 2. To address this issue, the committee divided variability into two types, experimental and biological, as described in the next section and Box 2-2.

Furthermore, in its discussion of cumulative risk, Science and Decisions: Advancing Risk Assessment recommended that the EPA also account for nonchemical stressors, vulnerability from

other chemical exposures, background risk factors, and their interactions with chemical stressors. In particular, consistent with a recommendation in the 2008 Phthalates and Cumulative Risk Assessment report (NRC, 2008), Science and Decisions: Advancing Risk Assessment (NRC, 2009) recommended that cumulative risk assessments should move away from the narrow focus on a “common mechanism of action” and broaden to encompass stressors that have the same or similar health outcomes. The 2009 report and more recent articles identify multiple intrinsic (or biological) factors (e.g., genetics, preexisting or underlying health conditions) and life stage (e.g., developmental) and extrinsic factors (e.g., nutritional status, built environment, psychosocial stressors due to factors such as poverty, job stress, and discrimination) that can increase susceptibility to chemical exposures. However, this recommendation was generally in the context of human epidemiologic or experimental animal studies, and the implications for moving toward an in vitro approach as suggested by NRC (2007) was not addressed.

Finally, in its discussion of the selection and use of default approaches (assumptions when chemical-specific data are not available), Science and Decisions: Advancing Risk Assessment recommended that the EPA address the “implicit” default of “no data = no risk”—that is, chemicals lacking epidemiologic or toxicologic studies are excluded from risk assessments and therefore assumed to pose no hazard or risk. Thus, this report also recognized the need to provide hazard and dose-response information in the absence of epidemiologic or experimental animal toxicology data, suggesting approaches such as quantitative structure–activity relationships (QSAR) or use of short-term toxicity tests to generate “actionable” predictions for risk assessment and as input in subsequent risk management decisions.

Application of Modern Toxicology Approaches for Predicting Acute Toxicity for Chemical Defense (NASEM, 2015)

In response to a Department of Defense request, a 2015 report made recommendations related to developing a toxicity-testing program not solely based on traditional mammalian acute toxicity testing for the specific task of predicting acute toxicity to safeguard military personnel against chemical threats (NASEM, 2015). The recommended approach consisted of (1) a conceptual framework linking acute toxicity to chemical structure, physicochemical properties, biochemical properties, and biological activity; (2) a suite of databases, assays, models, and tools applicable for predicting acute toxicity; and (3) a tiered prioritization strategy integrating (1) and (2) that balances the need for accuracy and timeliness. The tiered prioritization strategy starts with an initial chemical characterization based on available data (Tier 0), followed by use of in silico models (Tier 1), then by in vitro or nonmammalian bioassays (Tier 2), and finally traditional mammalian acute toxicity testing (Tier 3). This approach represents a refinement of the concept of tiered testing described in NRC (2007), specifically incorporating the fact that decision-making may be possible at each tier, and that subsequent tiers would only be implemented when inadequate data were available categorizing a chemical as high toxicity, low toxicity, or low threat due to factors unrelated to toxicity. This report also acknowledged the issue of variability in laboratory mammalian toxicity tests, noting that this may be a source of misclassification between toxic and nontoxic when such data are used to develop, calibrate, or evaluate performance of NAMs used in Tiers 1 and 2.

Using 21st Century Science to Improve Risk-Related Evaluations (NASEM, 2017)

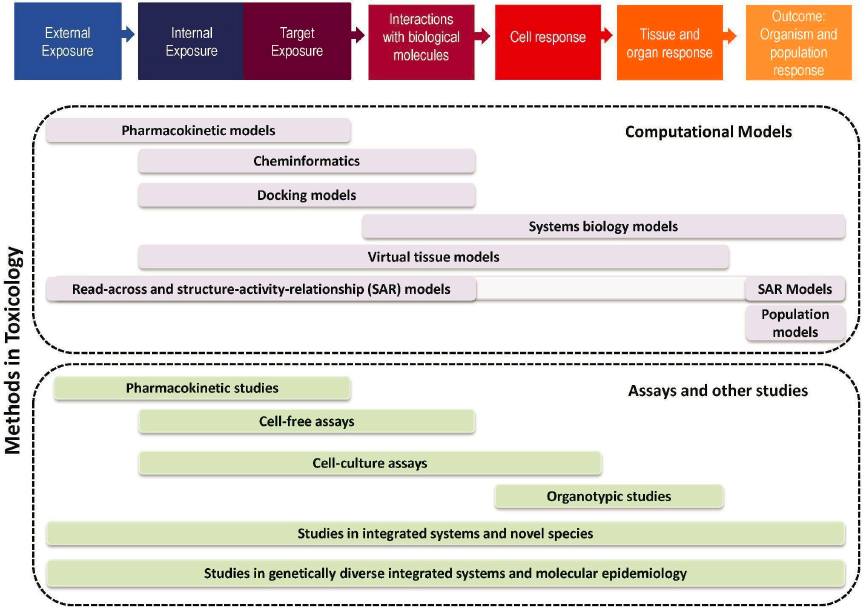

Released in 2017, this report sought to provide practical advice to agency-based decision makers on the incorporation of emerging tools and data streams into chemical evaluations. The report provided landscape assessments of the evolution of technologies within the fields of

exposure science, toxicology, and epidemiology, and how they fit into the source-to-outcome continuum to inform human health risk assessment (see Figure 2-1). It also outlined challenges within each field, including those associated with infrastructure (e.g., lack of systems for data sharing), tools (e.g., limitations in biological coverage and metabolism), and culture (e.g., siloed disciplines). To illustrate the uses and challenges of tools across the risk paradigm, the report utilized several case studies to highlight specific decision contexts in which new tools could be or currently were being applied including prioritization, individual chemical assessments, site-specific assessment (including mixtures), and assessments of new chemistries. Importantly, the committee highlighted “that testing should not be limited to the goal of one-to-one replacement but rather should extend toward development of the most salient and predictive assays for the endpoint or disease being considered.”

In addition to discipline- and decision-context specific discussions, the report also provided advice for advancing risk assessment to facilitate the health-protective incorporation of 21st century science, tools, and information into chemical assessment. The committee suggested that more flexible approaches be utilized in determining mechanisms by which stressors, including chemical and nonchemical stressors, could lead to increased risk (i.e., greater incidence or severity) of a particular disease outcome. For example, rather than restricting to simple binary relationships between single agents and single outcomes, risk assessment can more fully acknowledge that exposures to different chemicals can contribute to a single disease, and a single chemical can lead to multiple adverse outcomes depending on the duration, life stage, and level of exposure. To address the goal of conducting risk assessment based on pathways to toxicity rather than apical endpoints, approaches for analyzing modes of action or key characteristics have been developed that could be probed in nonmammalian assays. So far, these data sets are largely derived from animal data, but the report suggested key characteristics could help guide development and evaluation of the relationship between perturbations observed in assays and their potential human health hazard.

The committee also provided several recommendations on the validation of models and data. When validating new tools and methods (including individual tools, batteries, and processes), the committee found that clear definitions were critical, particularly regarding scope and purpose. Of critical importance is defining whether the tests were meant to replace existing tests or to provide additional information relevant to human health risks that are lacking in existing tests, as well as stating the specific decision context. Identifying explicit and well-defined comparators and reference chemicals was also essential in the validation of new tools. Clear guidelines for reporting both performance and results, as well as establishing clear mechanisms for data integration and for independent experimental reproduction of the test to improve data confidence, were also seen as important steps in developing validation procedures fit for the specific ways in which the tools and resultant data will be used.

Finally, the report contained several recommendations on the interpretation and integration of data in risk-based decision-making. The committee found that while data integration was acknowledged as an area of needed focus in previous reports (NRC, 2007), progress in this area was not robust. An empirical research approach utilizing case studies, cataloging, and combining data in systematic ways was needed. The committee also found that to facilitate the use of a sufficient component cause model in risk assessment, intentional development and cataloging of pathways, components, and mechanisms that can be linked to specific traits (e.g., key characteristics or key events in adverse outcome pathways [AOPs]) should be encouraged and increased. For data interpretation and integration, the committee did not find an immediate alternative to evidence-guided expert judgment but suggested that additional discussion among various stakeholders could help identify pathways forward that help ensure the protective use of emerging tools in risk-based decisions.

Human health risk assessment includes a variety of steps including hazard identification, exposure assessment, dose-response modeling, and risk characterization. When data on the relationship between toxicant concentrations and adverse outcome are available, a quantitative risk assessment with numeric exposure limits can be derived.

The toxicology methods captured in Figure 2-1 all potentially contribute insights for this process and its component steps. As an illustration, if the only data available are from animal models, then a species extrapolation to humans is needed. Toxicokinetic (TK) models and data provide such a connection to this process. Here, the time course of tissue and metabolism levels might be studied in animals and described using a TK model and the time course of these levels in humans represented using a TK model where the model parameters for humans (e.g., partition coefficients, tissue volumes, blood flows) are substituted for the animal parameter values.

There are many chemicals with little to no data to inform a risk assessment, particularly whole animal long-term bioassays or human epidemiology studies. Additional toxicology

methods, such as those in Figure 2-1, can provide additional insights for identifying hazards and potentially setting exposure limits.

Role of Computational Toxicology

A cross-cutting theme across all of these NASEM reports is the increasing role of computational toxicology, also known as in silico toxicology. This is an area of toxicology that uses computational methods and tools to support integrative approaches to chemical safety assessment via predictive modeling, analyses of complex data sets, and extrapolation among data streams. Multiple aspects of computational toxicology can be considered a new approach method (NAM). Some examples shown in Figure 2-1 (reproduced from NASEM, 2017a) include structure–activity relationship (SAR) toxicological assessments based on “read across,” chemoinformatic models that use chemical structure to make predictions for absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) parameters or toxicity alerts, PBPK models, QSARs, and molecular docking models. Indeed, each of the foregoing NASEM reports also envisioned an important role for such computational approaches. For instance, NRC (2007) highlighted the need for PBPK modeling to relate in vitro test concentrations to exposure. NRC (2009) suggested that QSAR, among other tools, could be used to address chemicals without adequate data for developing toxicity values. NASEM (2015) explicitly recommended use of in silico models in a tiered approach for predicting acute toxicity.

In a SAR-based read-across assessment, the target chemical for which a hazard/risk assessment is being conducted has a data gap for one or more toxicological endpoints. To fill the data gap, existing toxicological data from a source chemical that is similar to the target chemical (i.e., a chemical analog) are brought into the assessment. Databases that support searches based on chemical structure (e.g., the EPA’s Computational Toxicology Dashboard) have significantly helped the process for identifying chemical analogs. Some of these databases also have tools to enable a generalized read-across (e.g., the EPA’s GenRA tool) for determining analog similarity based on a variety of structural and biological descriptors. Structural similarity should only be considered as a starting place and should be supplemented with additional information related to physical–chemical properties, metabolic pathways, and expert-derived rules to filter out instances where specific chemical features would dramatically change the toxicity profile. Most recent advancements in the analog identification process include the identification of molecular scaffolds that can be searched for, and automation of expert-based rules.

Chemoinformatic approaches combine chemistry, mathematical, and statistical models to predict chemical properties and the behavior of chemicals in biological systems. Chemoinformatics techniques include molecular visualization, molecular fingerprinting, and molecular modeling. Molecular visualization allows researchers to visualize the three-dimensional structure of molecules, while molecular fingerprinting involves the use of algorithms to identify the chemical properties of molecules based on their molecular structures. Molecular modeling involves the use of computational methods to predict the properties and behavior of molecules based on their molecular structures.

QSAR modeling is a method within chemoinformatics that uses the structure of a chemical to quantitatively predict the activity that the chemical has toward a biological target (toxicodynamics) or that the body has toward the chemical (toxicokinetics). QSAR models need to be built using large data sets of compounds with known activities or toxicities, and they can then be used to predict the activity or toxicity of new compounds. QSAR models are widely used in drug discovery, environmental risk assessment, and regulatory toxicology.

Molecular docking is a computational method used to predict the binding of small molecules to proteins or other biological targets. It involves the use of algorithms to predict the orientation

and energy of the interaction between a molecule and a target. Molecular docking is used to predict the binding affinity of small molecules to targets and to identify potential drug candidates.

There is a growing interest in using in silico toxicology in risk assessment to predict the toxicity of chemicals and other substances, especially for the large number of unassessed chemicals for which little toxicological information is currently available. Techniques such as machine learning, deep learning, and neural networks are being applied to large data sets of chemical and biological data to develop predictive models that can be useful in helping to identify potential toxic effects of chemicals on human health but do not replace the need for expert judgment. Machine learning algorithms need to be trained on large enough data sets of chemicals to develop predictive models that can identify potential toxic effects of new chemicals. Deep learning techniques are being used to analyze large and complex data sets of molecular structures and biological data to identify patterns and relationships that can be used to predict the toxicity of chemicals. Neural networks are being used to model the interactions between chemicals and biological systems, such as enzymes, receptors, and other targets, to predict their toxic effects. Ensemble statistical techniques can be used to choose the best machine learning algorithms to apply to the data set and achieve more robust predictions. Computing power is increasing and getting less expensive, and this will enable an increasing degree of sophistication of computational toxicology tools and facilitate their application.

Workshop 2: Observations on Future of Toxicity Testing

The future of toxicity testing in human health risk assessment was also discussed in Workshop 2 (observations specific to the committee’s charge questions are summarized in subsequent chapters of this report). Key points made by participants parallel those discussed in NASEM reports discussed previously, in particular:

- Many participants emphasized the need for future toxicity testing approaches to address numerous long-standing, challenging issues, including the large number of untested chemicals, mixtures, differences in susceptibility across life stages, biological variability due to genetics, and the impact of broader environmental factors such as social disparities and environmental justice. It has been challenging for many existing laboratory mammalian toxicity studies, in particular guidelines studies, to address many of these issues.

- Across the case studies, it was suggested that the complexity of the biological pathways for many human health hazards would require toxicity testing approaches to be integrative and/or consist of batteries of tests.

- Several case studies also illustrated how novel in vitro and in silico toxicity testing approaches could be used in tandem with human epidemiologic studies, particularly given advances in exposure science and associated statistical methods.

- Numerous case studies also exemplified approaches that, rather than predicting apical adverse outcomes, focused on upstream markers and perturbations of critical biological processes, but noting the need to have biologically plausible connections between perturbations and adverse outcomes.

FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

After reviewing this background information on both the use of laboratory mammalian studies in human health risk assessment as well as recommendations from previous NASEM reports,

the committee determined that there were several implications with respect to addressing the Statement of Task, especially with respect to definitions of terms.

Finding: The 2007 NRC report Toxicity Testing in the 21st Century: A Vision and a Strategy proposed that in coming decades, new in vitro tools and computational systems biology approaches could provide sufficient insight to bridge the gap between chemical effects measured in human cells and health effects in people. While still a work in progress, this conceptual framework continues to inspire a new generation of researchers. The findings from the 2007 NRC report continue to be relevant.

Finding: The goal of toxicity testing for human health risk assessment is to protect human health, including (and prioritizing) susceptible and vulnerable subpopulations. There are several, sometimes conflicting factors relating to current and future toxicity testing that can support or hinder progress toward this goal. The 2009 report Science and Decisions: Advancing Risk Assessment (NRC, 2009) and the 2017 report Using 21st Century Science to Improve Risk-Related Evaluations (NASEM, 2017) continue to provide salient advice for toxicity testing under the specific context of use of human health risk assessment, particularly with respect to (1) expanding beyond the goal of one-to-one replacement of animal tests; (2) expanding whole animal testing beyond standard guideline-like studies; (3) addressing human variability; (4) addressing challenges in assay performance and validation; and (5) implementing best practices for data integration and interpretation.

Recommendation 2.1: The EPA should continue to use previous NASEM reports, especially Toxicity Testing in the 21st Century: A Vision and a Strategy, Science and Decisions: Advancing Risk Assessment, and Using 21st Century Science to Improve Risk-Related Evaluations, for advice and recommendations as to how to improve toxicity testing and human health risk assessment.

Finding: There are multiple sources of variability in toxicity testing data. In some cases, variability may be desirable, particularly when it can be informative of variability or increased susceptibility in humans and incorporated into human health risk assessment. However, in the context of assay validation and reproducibility, variability may not be desirable and can rather reflect technical rather than biologically meaningful differences. Therefore, the committee addresses the concept of variability according to its source: biological or experimental (see Box 2-2). This issue is discussed further in Chapter 3.

Finding: As shown in Figure 2-1, reproduced from NASEM (2017), previous NASEM reports noted that there is a continuum of approaches in terms of biological responses measured (interactions with biological molecules to population responses) and methods in toxicology (in silico, in vitro, “integrated” systems including in vivo experimental animals, and human epidemiologic), all with the potential to contribute information for human health risk assessment (specifically hazard identification and dose-response assessment). Most current risk assessments are based on apical outcomes from in vivo mammalian and human epidemiologic data, in addition to some use of computational, cellular, and other ex vivo assays for some mechanistic studies. Previous NASEM reports have recommended expanding the information used for risk assessment across this continuum, such as moving away from apical endpoints to encompass “upstream” biomarkers, such as key characteristics or key events in AOPs. NASEM has also provided recommendations on how best to evaluate human epidemiologic, experimental animal, and mechanistic evidence in the context of current risk assessments (see additional discussion in Chapter 5).

Finding: Currently, some of the data informing risk assessment arises from laboratory mammalian toxicity studies using a wide range of study designs, ranging from guideline studies commissioned by industry or government agencies to a diversity of studies published in the open scientific literature. Therefore, the committee defines the term “existing laboratory mammalian toxicity tests for human health risk assessment” to encompass any current in vivo, experimental toxicologic studies in nonhuman mammalian species that measure a marker on the exposure–outcome continuum starting from interactions with biological molecules to outcomes at the population level, which are not limited to “guideline” studies. The committee utilized this more general definition when addressing the charge questions related to “laboratory mammalian toxicity studies.”

Finding: Previous NASEM reports did not use the term “new approach method,” instead using a variety of terms to describe specific types of assays or information sources, such as those shown in Figure 2-1, which include

- Approaches by technology type

- In silico, in vitro, in vivo, and combination (e.g., in silico–in vitro) methods

- Specific subtypes (e.g., microphysiological systems) as shown in the individual boxes

- Approaches by toxicity indicator (e.g., based on bioactivity vs. apical outcome)

- Approaches by location in the exposure-to-outcome continuum (e.g., exposome, population-based models)

With respect to charge question 4, the issues “left unresolved” raised by NASEM (2017) related to assay validity and concordance apply beyond tests meant to “avoid use of animal testing” but instead addresses more broadly the development “of the most salient and predictive assays for the endpoint or disease being considered.”

Finding: The EPA’s definition of NAM as “any technology, methodology, approach, or combination that can provide information on chemical hazard and risk assessment to avoid the use of animal testing” is insufficient and inadequate to achieve the EPA’s goal of protecting human health for several reasons:

- What constitutes “new” changes with time, but the definition makes no reference to any timeframe. Therefore, it is awkward to label a particular assay a new approach method because either now or in the future, it may no longer be new.

- Not all approaches “to avoid use of animal testing” are “new.” Many approaches that can be used “to avoid use of animal testing,” including in silico approaches (such as read-across and QSAR) as well as cell culture−based assays (such as genotoxicity tests), have been in use for decades.

- It is not clear what is meant by the term “animal.” For instance, language in TSCA refers specifically to “vertebrate animal testing,” and not “animal testing” more generally. Moreover, the use of the term “animal” without additional specificity is confusing because nonmammalian species (such as zebrafish) are a major focus of many so-called NAM efforts, including being part of ToxCast and a developmental neurotoxicity testing battery under development in cooperation with the OECD.

- The part of the definition “to avoid use of animal testing” is confusing. For instance, many of the 21st century scientific approaches discussed in NASEM (2017) provide information that animal tests cannot provide and/or may be complementary to animal data. However, it is unclear whether this constitutes “avoiding” the use of animals. In addition, assays using primary cells from animals are not generally considered “animal studies” but require animals as a source of cells. Further, it is not clear whether “avoid” is meant to refer specifically to the 3 Rs of “replace, refine, and reduce,” or whether it is broader or narrower than the 3 Rs. For instance, TSCA specifically refers to approaches to “reduce and replace” vertebrate animal testing, which is more specific than “avoid.”

- It is not uncommon for toxicologists to interpret the “NA” in “NAM” as “nonanimal” as opposed to “new approach.” This misinterpretation causes significant confusion since the 21st century scientific approaches discussed in NASEM (2017) includes advances in animal studies (transgenic and population-based rodent models, alternative species, and more targeted testing), as well as advances in epidemiology (-omics and new biomarkers).

- There are many long-standing definitions for approaches that are considered alternatives to animal studies, such as those used by organizations such as the National Toxicology Program (NTP) Interagency Center for the Evaluation of Alternative Toxicological Methods (NICEATM), the Interagency Coordinating Committee on the Validation of Alternative Methods (ICCVAM), the Japanese Center for the Validation of Alternative Methods (JaCVAM), and the European Union Reference Laboratory for Alternatives to Animal Testing (EURL ECVAM).

- Although there is now global use of the term “NAM,” there is a lack of harmonization in how it is defined among different agencies and groups.

- In many cases, including in the EPA’s definition, “NAM” is defined in part by what it is not rather than what it is.

One result of these issues is that the EPA’s definition of NAMs is often construed too narrowly. Hence, for charge questions 4 and 5, the committee did not restrict its consideration only to assays that might be considered NAMs under the EPA’s definition, adopting the NASEM (2017a) view that these issues extend to “development of the most salient and predictive assays for the endpoint or disease being considered” (see Chapter 5).

In sum, the term “new approach method” is confusing, has not been consistently defined, may change with time, and appears to refer to heterogeneous information sources for human health

risk assessment, some of which may not be new. Terms such as “NAM” create a false dichotomy between data streams, all of which can be informative for human health risk assessment.

Recommendation 2.2: The committee recommends that the EPA broaden the definition of NAM so that it encompasses the range of strategies and approaches as discussed in the 2017 report Using 21st Century Science to Improve Risk-Related Evaluations. The EPA should develop additional terms to refer to specific subsets of approaches, such as by technology type, toxicity indicator, or location on the exposure-to-outcome continuum, as shown in Figure 2-1.

REFERENCES

Clark, M., and T. Steger-Hartmann. 2018. “A Big Data Approach to the Concordance of the Toxicity of Pharmaceuticals in Animals and Humans.” Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology: RTP 96 (July): 94–105.

Knight, D. J., H. Deluyker, Q. Chaudhry, J-M. Vidal, and A. de Boer. 2021. “A Call for Action on the Development and Implementation of New Methodologies for Safety Assessment of Chemical-Based Products in the EU—A Short Communication.” Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology: RTP 119 (February): 104837.

Monticello, T. M., T. W. Jones, D. M. Dambach, D. M. Potter, M. W. Bolt, M. Liu, D. A. Keller, T. K. Hart, and V. J. Kadambi. 2017. “Current Nonclinical Testing Paradigm Enables Safe Entry to First-In-Human Clinical Trials: The IQ Consortium Nonclinical to Clinical Translational Database.” Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 334 (November), 100–109.

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2015. Application of Modern Toxicology Approaches for Predicting Acute Toxicity for Chemical Defense. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/21775.

NASEM. 2017. Using 21st Century Science to Improve Risk-Related Evaluations. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/24635.

NRC (National Research Council). 2006. Toxicity Testing for Assessment of Environmental Agents: Interim Report. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/11523.

NRC. 2007. Toxicity Testing in the 21st Century: A Vision and a Strategy. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/11970.

NRC. 2008. Phthalates and Cumulative Risk Assessment: The Tasks Ahead. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/12528.

NRC. 2009. Science and Decisions: Advancing Risk Assessment. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25009905/.

Olson, H., G. Betton, D. Robinson, K. Thomas, A. Monro, G. Kolaja, P. Lilly, J. Sanders, G. Sipes, W. Bracken, M. Dorato, K. Van Deun, P. Smith, B. Berger, and A. Heller. 2000. “Concordance of the Toxicity of Pharmaceuticals in Humans and in Animals.” Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology: RTP 32(1): 56–67.

Parasuraman, S. 2011. “Toxicological Screening.” Journal of Pharmacology & Pharmacotherapeutics 2(2): 74–79.

Rusyn, I., W. A. Chiu, and F. A. Wright. 2022. “Model Systems and Organisms for Addressing Inter- and Intra-Species Variability in Risk Assessment.” Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology: RTP 132 (July): 105197.