Supporting and Sustaining the Current and Future Workforce to Care for People with Serious Illness: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: Proceedings of a Workshop

Proceedings of a Workshop

INTRODUCTION1

Providing high-quality care for people living with serious illness requires an adequately sized and well-trained and prepared workforce comprising a range of health professions, such as physicians, nurses, social workers, pharmacists, direct care workers, chaplains, and physical and occupational therapists. However, there is a significant shortage of professionals to meet the increasing numbers and far-ranging needs of those who are seriously ill—a shortage projected to worsen as a result of the aging of the workforce and the challenges to health professional well-being (Kamal et al., 2017, 2019; Lupu et al., 2018). These factors underscore the importance of supporting and sustaining the current and future workforce to care for people with serious illness.

To explore a broad range of workforce-related issues, the Roundtable on Quality Care for People with Serious Illness hosted a public workshop, Supporting and Sustaining the Current and Future Workforce to Care for

___________________

1 The planning committee’s role was limited to planning the workshop, and the Proceedings of a Workshop has been prepared by the workshop rapporteurs as a factual summary of what occurred at the workshop. Statements, recommendations, and opinions expressed are those of individual presenters and participants and are not necessarily endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, and they should not be construed as reflecting any group consensus.

People with Serious Illness, held on April 27–28, 2023. This workshop explored strategies and approaches to address major challenges, such as health professional well-being, workforce shortages, and advancing the diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) of the workforce caring for people of all ages and all stages of serious illness. This workshop builds on the roundtable’s 2019 workshop, Building the Workforce We Need to Care for People with Serious Illness (NASEM, 2020).

The 1.5-day workshop unfolded across eight sessions. The first session featured a panel of members of the interdisciplinary care team sharing their lived experience caring for people with serious illness, which had been made even more difficult by the COVID-19 pandemic. These firsthand accounts were followed by an overview of the workforce that cares for people with serious illness—who they are, the roles they play, and the challenges they face. The third session examined ways to better support the well-being of the health care workforce. The fourth session featured a discussion on how to create a caring and compassionate environment for patients and those who care for them. The fifth session highlighted an important segment of the workforce caring for people with serious illness: the direct care workforce. The final session explored another key challenge, advancing diversity, equity and inclusion in the workforce caring for people with serious illness.

The second day of the workshop began with a session highlighting several examples of promising models and innovative approaches to workforce recruitment, training, and retention. The final session featured several experts who shared their perspectives on some promising strategies to support the vital work of those caring for people with serious illness.

This Proceedings of a Workshop summarizes the presentations and discussions. The speakers, panelists, and participants presented a broad range of views and ideas. Box 1 summarizes suggestions from individual participants for supporting and sustaining the workforce to care for people with serious illness. Appendixes A and B contain the workshop Statement of Task and workshop agenda, respectively. The speakers’ presentations (as PDF and audio files) have been archived online.2

___________________

2 For additional information, see https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/04-27-2023/supporting-and-sustaining-the-current-and-future-workforce-to-care-for-people-with-serious-illness-a-workshop.

OPENING REMARKS

Peggy Maguire, president of the Cambia Health Foundation, shared that the workshop was dedicated to the late Jared Randall Curtis; before succumbing to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, he was a pulmonary critical care and palliative medicine physician and a prolific researcher and mentor to many in the field of serious illness care. After receiving his diagnosis, Curtis shared four life lessons: (1) work with people you like or even love, (2) take sabbaticals to recharge, (3) live every day like you have a terminal illness, and (4) focus on what is important and prioritize family (Curtis, 2022). Maguire said that she had the opportunity to interview Curtis after his diagnosis, and he told her that his greatest legacy was the people whose

lives he had touched through his work. “Today, through this workshop, we pay tribute to him by working to improve serious illness care and support the workforce,” explained Maguire.

Brynn Bowman, chief executive officer of the Center to Advance Palliative Care, observed that this workshop takes on a huge and extremely complicated facet of health care, at a time when the broader health care workforce faces serious challenges. Noting that workforce shortages existed well before the COVID-19 pandemic, Bowman pointed out that many have left the field over the past 3 years, and for those who remain, life is not yet back to normal. “There is a lot of lingering trauma, moral distress, and exhaustion that we are still coping with,” observed Bowman. “That really

is the backdrop for all of the conversations we will hear over the next day and a half,” she added.

JoAnne Reifsnyder, professor of health services leadership and management at the University of Maryland School of Nursing, remarked that acute care–based palliative care, community-based palliative care, and hospice care have provided a road map for delivering person-centered and family-centered interprofessional care for people with serious illness. She added, however, that serious illness exists beyond those settings and includes care provided in nursing homes, mental health institutions, pharmacies, homes, and by programs such as the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE). “We can learn from our palliative care colleagues about workforce issues, barriers, and successes,” observed Reifsnyder. “In turn, our palliative care colleagues … can learn from folks who are delivering care in other settings to people with serious illness about what we need to do to shore up and sustain our workforce for the future.”

Reifsnyder explained that the term “direct care workforce” refers specially to people at the bedside, such as CNAs, direct care workers, home care workers, and community health workers. Members of the direct care workforce, she said, are underpaid and often need to take multiple jobs to sustain themselves or leave the health care setting. “That is not healthy for them and that is not sustainable for the serious illness workforce,” emphasized Reifsnyder. For that reason, she said, the workshop would examine the system changes needed to enable those critically important individuals to bring their best to their jobs and be recognized for that. In addition, she said, a theme throughout the workshop would be the issues and actions that the health care enterprise has or has not taken to support DEI in health care settings broadly and the serious illness care workforce specifically.

On a final note, Reifsnyder noted that supporting and sustaining the workforce will require radically rethinking, not merely tweaking, the aims of serious illness care and developing innovative solutions to provide serious illness care while ensuring attention is paid to the well-being of the workforce delivering that care. “We know that while some systems might be modified, others will be probably disrupted and redesigned entirely,” she noted. Accomplishing this radical rethinking will require transformational leadership at the micro and macro levels, she added.

VOICES FROM A WORKFORCE IN CRISIS

The opening session featured a discussion moderated by Victoria Leff, palliative care consultant on health care provider wellness and an adjunct instructor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, about ongoing workforce challenges from the perspectives of members of the interdisciplinary team caring for people with serious illness. Leff opened the discussion by asking John Tastad, chaplain and spiritual care and advance care planning coordinator at Sharp HealthCare in San Diego, CA, to talk about how providing such care over the past 3 years has affected him and his colleagues. Tastad explained that he has been a hospice chaplain for 22 years and is the coordinator for a spiritual care team that works with seriously ill people in palliative care and hospice. In preparing for the workshop, he asked his colleagues to give him an idea of what the last few years were like, and they used words such as “tired,” “worried,” “vulnerable,” “frustrated,” and “impermanence.” Tastad noted that a significant challenge has been dealing with the sense of incredible powerlessness to help anyone in a significant way.

Tastad explained that when providing spiritual care, the best intervention is to be “a kind, thoughtful, and compassionate presence that aligns with the patient’s values, beliefs, and religious perspectives.” This requires “swinging into that context,” and when that is impossible or a barrier is present, caregivers feel tired, worried, vulnerable, impermanent, frustrated, and powerless. He recalled how he was asked to come to a dying patient’s home to administer Catholic last rites, and after donning all his personal protective equipment (PPE), “[m]y glasses fogged up because of the rain and the mask and I couldn’t connect,” said Tastad. “I did my best to behave like a priestly presence that provided comfort to the afflicted and the dying.”

Tastad recounted that after returning to his car, removing his PPE, and driving away, he began to cry and could not stop. The intense emotions, he explained, came from feeling distanced from the person he was there to help and a sense of powerlessness. “I think we’re still feeling that now in serious illness care, probably in some different ways as we deal with staffing issues,” among other concerns, he noted. Tastad concluded by saying he was grateful for the “chaplain seat at the table as the interdisciplinary care team member,” and he asked workshop participants to hug a chaplain that they know.

Sharon Chung, a clinical therapist at the Center for Grief & Loss in St. Paul, MN, explained that they left the hospital setting in the fall of 2020

because, like many social workers, they felt moral injury because of “the lack of moral obligation of many of our health care systems.” Chung explained that this feeling had become “an ongoing sense of perpetuating harm and medical trauma that I was unable to stop or mitigate in my role as a social worker.” Chung described feeling powerless and “devalued by people in positions of power.” Perhaps most heartbreaking for Chung was what they termed the “ableist attitude” about what determined quality of life. This attitude translated into messages that “[i]f someone wasn’t able to walk or talk, then it really wasn’t a quality of life worth saving,” described Chung.

Chung emphasized that in leaving that hospital, they did not resign from health care but rather shifted to a different care setting. In their role as a psychotherapist, they have tuned into the harm, trauma, and the immense grief and loss that they and others feel as health care providers and caregivers for people with serious illness. Chung shared that they were fearful that in leaving the hospital setting, they would step away from palliative care. However, their new role has only deepened and enriched their ability to work on the front lines of serious illness care. Chung explained that about 25 percent of their caseload is health care providers, 20 percent are caregivers of people living with serious illness, and 30 percent are people living with serious illness. Chung shared that they find it enriching to work with all these different groups of people.

Shawndra Ferrell, system clinical manager for advance care planning and shared decision making in serious illness at Advocate Aurora Health in Downers Grove, IL, said she, too, recently left the hospital setting and shifted into an administrative role. She said it was distressing to make that decision because it felt that she was somehow abandoning the hospital she had worked at for nearly 4 years as the sole palliative care provider, both before and during the pandemic. “You develop that care and compassion for the community and for each one of those patients, and then, somehow, when you can’t handle it anymore, you leave,” Ferrell observed, “but it also means you leave them hanging, or at least that’s how it feels.” She pointed out that although no one made it seem like she was abandoning them, she still has that feeling.

Ferrell believes the health care community today is paying more attention to the importance of self-care for health professionals and supports the notion that “it is okay to not be okay.” Although she appreciates that hospitals set aside rooms for staff to take a break, for many overwhelmed by the pressures and challenges, it is impossible to take in positive messages. Ferrell did not realize that she was struggling until she started needing a

break between each consult. “It was getting harder and harder to start over and say the same things with the next group of people as if you didn’t spend 2 hours pouring it all out for the last patient.”

Ferrell explained that she has discovered ways to support communities while not being on the front lines. She tells herself that perhaps she took her previous role as far as she could, and it was time for someone else to take over. Ferrell recalled that the “lightbulb moment” for her was that as much as she and her colleagues care for and take a holistic approach to the patient, it is also important to consider the whole person providing that care. That was what was missing for her and something she did not know how to do. Ferrell said a year after changing jobs, she is still learning that it is important to care for oneself.

Rachel Adams, physician executive director of the palliative care service line at MedStar Medical Group and division chief for palliative care at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, said her palliative care story dates to her adolescence, when members of her small family began becoming seriously ill, including her father, who died of cancer when she was 18. She recalled many complicated interactions with the health system during her father’s illness. From this experience, she knew she wanted to be a healer and protector. “I wanted to make others feel seen and heard. I wanted to find narrative in moments of loss with patients and families, and I wanted to create space for people to land and feel safe,” explained Adams.

Adams characterized the COVID-19 pandemic as a huge disrupter, causing intense conflict in her roles everywhere she turned. “I was confused about my identity with others and in my physician role,” she said. Before COVID, Adams rarely felt unsafe in the hospital and was never worried about exposing her family to danger. However, she became fearful of in-person interactions with her patients— “the people I meant to protect”—colleagues, and her family. “I wasn’t afraid of my family, but I was afraid for my family. My kids hadn’t signed up to be health care workers,” she explained. This fear for her family’s health contributed to “a time of deep, deep sadness, and it still makes me sad,” Adams noted.

Adams described the experience of one of her patients, an immunocompromised nurse who was admitted with COVID and continued testing positive over a month-long stay. Given her active case of COVID, she was not allowed to see her daughters or have any visitors, which left her feeling depressed and alone. Adams noted that her patient benefited from chaplaincy services, even though the chaplain had to offer prayers from outside her room via video or audio. Eventually, when it was clear that she was not

going to survive, only one family member was allowed to visit. Adams said she is still affected by experiences such as this and the distress that families, patients, and clinicians experienced. A trainee she mentored is still talking about the phone calls she had to make to tell families they could not see their loved one at the end of life.

Another concern that Adams shared relates to the loss of faith in science and medicine and how that is affecting clinicians. She lost a friendship with someone who became deeply opposed to masks and vaccines, even after she told him stories that contradicted his belief that patients dying of COVID would have died of something else anyway. “We continue to express care for one another, but our friendship is irrevocably changed and informed by mistrust,” said Adams, who wonders what this means for the nationwide schism of medical distrust.

Emphasizing that she still loves being a doctor, particularly working in palliative care with interprofessional teams, Adams remarked that “I have beautiful, successful stories about how we overcame barriers during COVID,” she explained, and how “we found novel ways to nourish human spirits.” She is grateful for the knowledge she gained from her experiences during the pandemic, particularly a better understanding of medical mistrust on the part of Black Americans and marginalized communities. She also has a heightened appreciation for health care workers who continue to show up for people in need.

LaToya Francis, a CNA at Inspire Rehabilitation and Health Center in Washington, DC, and nursing student at the University of the District of Columbia Community College, said she appreciated being invited to speak because she feels that CNAs are among the most undervalued workers in health care. She observed that although the other panelists spoke about shifting from clinical care to different positions to protect their mental health or protect themselves physically from COVID-19 or any other disease that might affect them, the ability to make such a change is a luxury that most CNAs do not have. Francis noted that she is constantly worrying about exposing her family to the virus, “which definitely affects my mental health, thinking about what I am going to bring home to my 3-year-old son who is immunocompromised and has asthma.”

Francis noted that she recently stopped working at a facility that was not meeting basic needs for PPE, which put staff in the dangerous position of having to reuse masks and exposing patients to potential infection. “Do you know how that feels on a day-to-day basis? To not be respected that much, to not get clean masks outside every room appropriately as

they should be,” asked Francis. “Hospitals care more about saving money in any way, shape, or form, or trying to monitor people from stealing masks.”

Francis emphasized that this is the kind of trauma CNAs deal with on a daily basis, whether it is not having adequate PPE or being the only CNA on a floor with 16 patients and trying over a 12-hour shift to provide total care without any help turning or cleaning each one. Compounding these challenges is that Francis, a single parent with two children, has great difficulty finding childcare while working two jobs to support her family. As an example, she said she would get off a 12-hour shift at 7 in the morning and then spend a few hours as an employee of a home care company. Even with multiple jobs, she has trouble paying her rent.

Noting that many facilities pay less than $20/hour to CNAs, health care workers charged with caring for patients with serious illness or dementia, Francis pointed out that “CNAs are leaving the field and going to jobs like Amazon, McDonald’s, even Walmart” that are “not as stressful” and “pay a little bit better.” Francis shared how degrading it is to have to tell her children that she cannot afford to get them a treat from the ice cream truck. “The ice cream truck shouldn’t be a luxury for somebody that’s taking care of critically ill people on a daily basis,” said Francis. Her low-paying job has resulted in housing insecurity for her and her children.

Francis explained that with the help of family and friends, she began nursing school in May 2022 to obtain the necessary training to find a better-paying position. Francis pointed out that pay and inadequate staffing affects patient care, noting how important it is to have “two or three more people to work with on a night shift” rather than a facility insisting that staffing is adequate. She remarked, “If we had better pay, we would have better staffing. It goes hand in hand. Get better staffing in these facilities and watch how much better-quality care we can give.”

Panel Discussion

Leff opened the discussion by commenting that she worries that although Francis feels she is not being heard, health care leadership may not want to hear what Francis has to say. Chung emphasized that the sense of trauma and harm the medical system perpetuates for both patients and caregivers highlighted by several of the speakers should resonate with all attendees. “What just strikes me in everyone’s story is that there are layers of loss,” observed Chung. The feeling of powerlessness, sense of abandoning

patients and teams by leaving the hospital setting, and fear of bringing harm home to family members can all feel like a loss, Chung added.

Chung pointed out that one of the biggest falsehoods to come out of the pandemic was the idea of health care heroes. “To think that our strength and our self-care is enough to carry us through is such a falsity,” they said. “I think there needs to be a significant shift from strength-based care to grief-informed and trauma-informed care.” Cultivating resiliency, they said, is informed by the trauma and grief of providers, patients, and caregivers. Focusing on grief and loss creates the opportunity to understand some of the life choices people have had to make that brings them to the place of working with them in a serious illness context. “When we can really see some of the lifestyle choices that people have made through a lens of grief and trauma, it really then allows us to see the whole person, to see the history, the trauma, the legacy of history and loss and trauma that has shaped people to where they are when we are sitting with them face to face,” explained Chung.

Referencing Adams’ and Francis’ remarks about underserved areas and care for patients from underrepresented populations, Ferrell pointed out that every health care system in the country has new initiatives to better address these needs. However, Ferrell questions the data that indicate people are more satisfied with their care and is concerned that surveys are not asking the most appropriate questions that would enable health systems to truly understand patient satisfaction. In fact, she said, she sees evidence that the situation has not improved. For example, she received a call from a patient’s family who started by calling her “sis.” “You hear that, and you immediately understand he’s not looking for the nurse practitioner who’s taking care of his loved one. He is trying to connect to somebody, to the part of me that he hopes looks like him and he is like ‘sis, tell me the truth,’” said Ferrell. Emphasizing the importance of trust, Ferrell pointed out that that person hoped that he could trust Ferrell to tell him the truth, which contributed to her struggle when she left the hospital setting, because she worried that the next person who called looking for someone to trust would not have “sis” around to speak with them.

Ferrell emphasized that those who care for people with serious illness are still in a space where they must find support among themselves. She emphasized that health care was “a broken and imperfect system prior to COVID” and that the pandemic “shown a bright light on all the things we already knew.” Ferrell added: “We’re still doing the work … but the workforce itself is struggling.”

Adams found it unacceptable for anyone to have a job that does not allow them to feel whole or carry out its basic functions. Survival should not be part of the job, she emphasized, so the question is how to do more than survive—to actually thrive. She noted that most nurses she works with graduated only a year or two before yet are already dealing with complex cases. Her worry is that it will be difficult to retain them. “I just think that the workforce right now is really ill prepared to manage some of what they’re facing, and I worry about them,” said Adams.

Ferrell remarked that nurses today are “fighting an entirely different beast” than what she experienced when she first became a nurse 26 years ago. She suggested that a solution is to work in an interdisciplinary team so that one person need not do all the work and new team members will have coworkers to answer questions they might have.

Leff noted that the problems the panelists raised are not new to anyone in health care but were significantly amplified by the pandemic. She hoped that the panelists’ presentations would inform the discussions throughout the workshop and remind everyone of the many areas to which attention must be paid. Leff thanked the panelists for their “courage and vulnerability.”

Audience Q & A

Workshop attendee Allie Shukraft, from Atrium Health, asked the panelists for suggestions on how to help early-career direct care workers who may experience moral distress because of what they view as decisional misalignment between what the patient and family are choosing and what their health care teammates believe they would choose in that instance, particularly if the teammates do not recognize or misunderstand the cultural factors that play into decision making process. Francis said she would keep advocating for the patient and doing her best to serve as the voice of the patient. She also recommended not backing down if told that it is wrong to advocate for the patient, which is something CNAs experience regularly. Ferrell said bedside workers need to advocate for themselves and bring in others, such as a chaplain, social worker, ethics team member, or someone from the risk management office, to help them cope with their distress.

Ferrell emphasized that it is important for bedside workers to remember that they are part of a team and rely on the resources that teammates can provide. “If you can’t get those resources, make somebody listen and ask them to get them for you, because you’re not going to get it if you just

sit there and suffer in silence,” said Ferrell. She added that when moral distress is not addressed, the worker can carry that from patient to patient and from work to home. Ferrell stressed the importance of “advocating for yourself and building a personal team, even if you don’t feel like you have a team.” Adams agreed that relying on team members is great advice. She also said that the palliative care team is often a group that others throughout the hospital recognize as one that will listen to the patient and amplify the patient’s voice.

Tastad noted that groups across the country, such as the California Coalition for Compassionate Care, work to get ahead of the moral distress from the “bedside guessing games” and decision making by holding skillful conversations with patients that inform decision making well before a crisis. In so doing, fewer clinicians have to face the moral distress or trauma that comes from having to make these difficult choices when caring for their patients. Leff added there should be an effort to tell people when they begin this work that it will be difficult and cause moral distress and they will need to work with their colleagues and have support from each other and their institutions. “If you’re not experiencing moral distress in this work, I’m worried about you,” noted Leff.

An audience member from the Norfolk Community Services Board asked what it would look like if panelists’ stories about the challenges they face in their positions prompted action to address those challenges. Francis replied that more facilities would allow for flexible work schedules to accommodate staff that must work multiple jobs to support their families and secure childcare for nontraditional working hours and better training opportunities would be provided for CNAs to grow and have opportunities to advance. She noted that her facility is trying to start a certified medical technologist program that would alleviate some of the nurses’ burden and allow for CNAs or certified nursing technicians to receive a salary increase and career boost. It would also help CNAs gain additional experience necessary for furthering their nursing careers.

OVERVIEW OF THE CURRENT AND FUTURE STATE OF THE HEALTH CARE WORKFORCE

In the workshop’s second session, Bowman provided a broad overview of all different components of the workforce that care for people with serious illness, and the key current and future challenges. She emphasized that although the workshop was not focused on the pandemic, it would be

impossible to have a workshop about the workforce without acknowledging the pandemic’s intense and enduring impact on patients, families and the workforce.

Bowman pointed out that the pandemic drew attention to the existing crisis of health care worker burnout (Surgeon General of the United States, 2022). According to the National Council of State Boards of Nursing, 20 percent of nurses nationwide are projected to leave the profession in the next 5 years (Martin et al., 2023). More than half of all nurses report feeling drained several days a week or every day, with fatigue and burnout most marked among nurses with less than 10 years of experience. “Our nursing workforce has had experiences so distressing and so exhausting and feel so little supported that they’re considering leaving the profession,” said Bowman.

Another stressor is providers’ increasing administrative burden. A national study of office-based physicians found that they spend an average of 1.84 hours a day on documentation and administrative duties outside of work hours (Gaffney et al., 2022). “That is time spent not practicing connecting with patients, not using that hard-fought, expensively gained skillset, but instead putting in administrative time based on a complicated and archaic payment system,” said Bowman. She also pointed to the results of a survey showing that only 45 percent of frontline clinicians trust their organization’s leadership to do what is right for patients and only 23 percent trust their organization’s leadership to do what is right for workers (Medlock et al., 2022). Undoubtedly, she said, these figures correlate with burnout felt by so many health care professionals.

Bowman noted that when considering the serious illness care workforce, palliative care teams and specialists immediately jump to mind; adult and pediatric specialists, home health aides, primary care teams, geriatric teams, family caregivers, staff at long-term care organizations and hospice organizations, and hospital staff are also included. In short, said Bowman, nearly everyone in the health care workforce cares for someone with serious illness at some point.

Bowman outlined the key components of a framework for an optimized workforce to care for people with serious illness:

- Adequate number of people representing the right mix of disciplines to provide the care patients with serious illness need;

- Workforce diversity that reflects patient demographics;

- A workforce that is available when patients need care;

- A workforce appropriately trained to meet patient needs;

- A system that supports the serious illness care workforce by providing the time, space, resources, and support to provide the services needed by those with serious illness; and

- A system that formally and explicitly prioritizes professional well-being.

Reviewing the components of the framework, Bowman cited a significant increase in the number of specialty certified hospice and palliative medicine physicians for both children and adults over the past couple of years. The current figure of more than 7,100 adult hospice and palliative care physicians translates to a ratio of approximately one for every 1,600 patients who might need them. For other professions such as nursing, the situation is even more dire. The pioneering nurses working in palliative care, for example, are starting to retire, but the pipeline has not been backfilled adequately, Bowman stressed.

Taken together, said Bowman, these numbers indicate that palliative care teams are inadequately staffed. According to the National Palliative Care Registry, only 41 percent of adult inpatient palliative care programs across the nation have a full interdisciplinary team, defined as chaplains, social workers, nurses, advanced practice nurses, and physicians (Rogers and Heitner, 2019). Moreover, nearly 20 percent of adult-serving programs do not have a dedicated physician, over 30 percent do not have a dedicated, full-time social worker, and nearly half do not have a dedicated chaplaincy full-time equivalent position.

Data also reveal that palliative care staff are not adequately trained, said Bowman. According to the Palliative Care Quality Collaborative and National Palliative Care Registry, 21 percent of inpatient palliative care programs have no specialty certified staff, and nearly half of registered nurses and advanced practice registered nurses on palliative care teams are not specialty certified. “We see these gaps, and this is alarming because we have a patient population with very complex needs, and we are the line of last resort in many cases,” said Bowman.

Despite the absence of data on the diversity of palliative care workforce specifically, Bowman said it is safe to assume based on health care writ large that the current serious illness care workforce is not as diverse as the patient population. Bowman noted that there are multiple research efforts underway to understand precisely who makes up today’s palliative care workforce and multiple initiatives to attract diverse clinicians to the serious illness care

specialty, but these will take years to bear fruit (Bell et al., 2021; Quigley et al., 2019).

A 2021 survey of 150 palliative care program leaders found that 43 percent of respondents were moderately or extremely concerned about the emotional well-being of their teams, and 93 percent reported some level of concern (Rogers et al., 2022). Bowman found it interesting that 69 percent of their programs had supported the well-being of non-palliative-care colleagues. Overall, she said, despite gains over the last decade, the workforce is not large, well-trained, or well-supported enough, particularly in the face of significantly increasing demand.

Bowman suggested an effective national workforce strategy for palliative care would start by expanding the specialty pipeline of people being trained and certified by focusing on students from preprofessional programs and midcareer individuals who resonate with the work they see palliative care teams providing. This would be coupled with an explicit effort and investment in attracting diverse professionals to the specialty. It is also important to train all clinicians in the core skills of palliative care, given that there will never be enough palliative care specialists to care for every patient. “There is no reason that we shouldn’t be able to provide person-centered care and attention to quality of life in every interaction that patients have with the health system,” said Bowman. A final component of the strategy involves efforts to leverage value-based payment to achieve interdisciplinary care.

Bowman emphasized the importance of providing basic education in palliative care skills for all nonspecialists who care for people of all ages with serious illness. Such basic education would include, for example, how to have a skilled conversation about the individual’s prognosis and understand a patient’s fears and concerns. Education and training are also needed for how to set goals, manage pain and symptoms, and support caregivers. Bowman noted that several institutions do a good job with this type of education in preprofessional clinical education programs.

Bowman pointed out that Aquifer,3 a medical education organization that provides nearly every U.S. medical school with curriculum modules on clinical care topics that have rarely made it into the standard curriculum, is finalizing a palliative care curriculum to which all of its medical school clients will have access. To inform this project, Aquifer staff conducted

___________________

3 See https://aquifer.org/courses/aquifer-excellence-in-palliative-care (accessed September 15, 2023).

focus groups and a national survey of medical students. Medical students, Bowman stressed, want training in palliative care skills in order to

- help them understand the differences between palliative care and hospice to recognize a patient who needs palliative care;

- better manage care transitions, learn how to approach serious illness conversations and navigate patient/family/team conflicts;

- learn about ways to manage pain;

- manage the risks from opioids; and

- understand ways to address the spiritual and cultural concerns their patients might have.

Given this broad range of interest, the problem, noted Bowman, is not that clinicians in training do not think palliative care is important but rather that current curricula do not prioritize it.

Bowman noted that education resources are available and suitable for clinicians interested in basic palliative care education, including material from Ariadne Labs,4 the California State University Shiley Haynes Institute for Palliative Care,5 the End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium,6 and the Center to Advance Palliative Care.7 Eighteen certificate programs exist nationwide for those who may not have the time, capacity, or need for full specialty training, along with one Ph.D. program offered by the University of Maryland and a variety of continuing education opportunities in communication, symptom management, and other palliative care skills. She noted that most people using the Center to Advance Palliative Care’s educational materials are non-palliative-care clinicians. She explained that the number of people using those materials has more than tripled, from less than 50,000 in 2016 to approximately 175,000 in 2022. Other organizations offering similar materials report the same trend (PHI, 2022). “There seems to be a growing understanding that these skills are important, that we have education gaps, and that they need to be filled,” said Bowman. Nonetheless, she said, most of these education initiatives for midcareer clinicians depend on them being passionate enough to find the educational opportunities themselves or ensuring that their teammates can connect

___________________

4 See https://www.ariadnelabs.org/serious-illness-care/ (accessed September 7, 2023).

5 See https://csupalliativecare.org/ (accessed September 7, 2023).

6 See https://www.aacnnursing.org/elnec (accessed September 7, 2023).

7 See https://www.capc.org/ (accessed September 7, 2023).

with these programs. While a growing number of training programs exist, clinicians are not currently required to acquire such skills, noted Bowman.

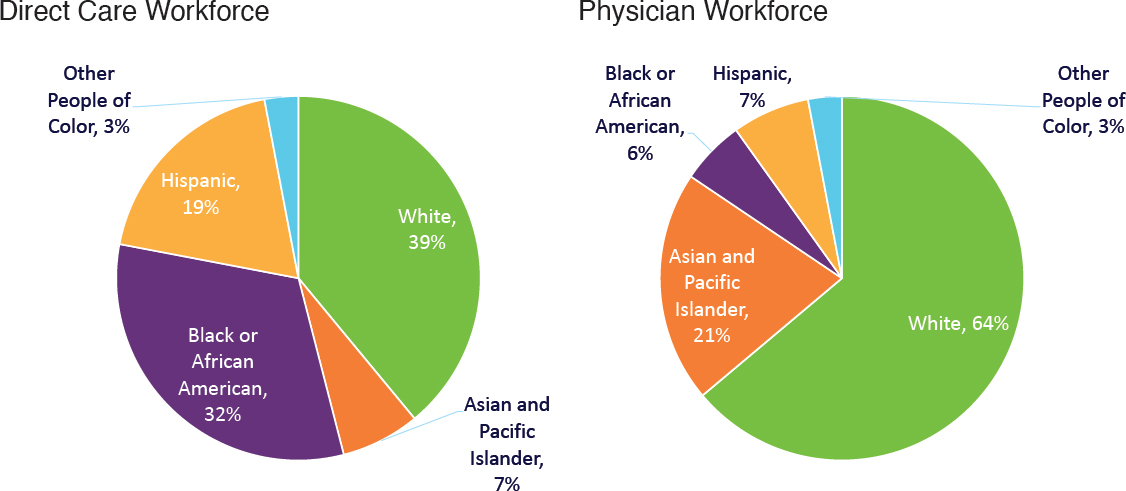

Shifting the focus to the direct care workforce, Bowman next explained that direct care workers provide intimate, day-to-day services for individuals with serious illness. Compared to physicians, they are disproportionately female and non-White (see Figure 1) and include personal care aides, home health aides, and nursing assistants across long-term care settings. Their median annual salary is $21,700, with 43 percent relying on public assistance (PHI, 2022). “As a country, we should be embarrassed that this is the case,” said Bowman. “We are undervaluing these positions that provide such critical care to our older and sick [patients] and patients living with disabilities.” The consequence is that turnover was 65.2 percent in 2020 (Holly, 2021).

Bowman noted that the payment landscape is trying to evolve to enable more care being provided through home and community-based services, which will require an even larger direct care workforce. Although that workforce has grown over the past several years, the number of people who need those services has grown faster (Kreider and Werner, 2023). As a result, the ratio of workers to potential recipients has worsened over the last decade, Bowman explained.

Bowman connected the lack of adequate direct care workers to the fee-for-service payment system that prioritizes the work of billable clinicians and limits access to in-home services and nonmedical services, such as personal care and support for social needs that improve patients’ quality of life. In contrast, she noted, a value-based payment system allows for staffing flexibility to better meet social and spiritual needs and pushes care out of the hospital and into the home and community, which has led to the proliferation of independent provider organizations that are laser focused on meeting patient needs at home and avoiding hospitalizations.

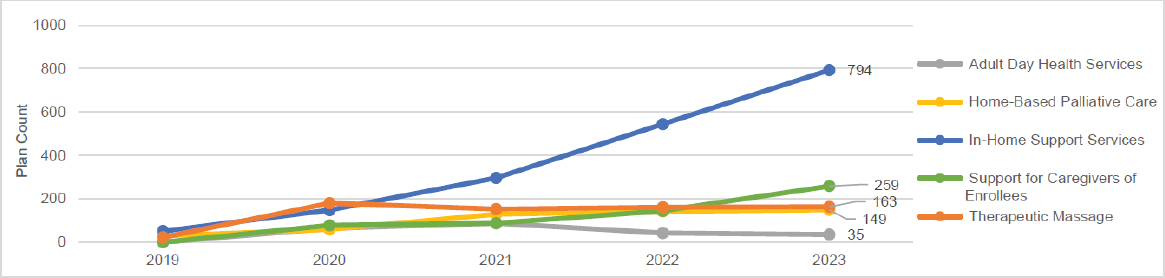

Data on supplemental benefits provided by Medicare Advantage (MA) plans indicate that a growing number of MA plans are providing home-based palliative care benefits to their patients (see Figure 2). Bowman pointed out that it is unclear exactly what some of these plans mean by home-based palliative care, and there is no accountability in terms of whether the home-based palliative care services meet national quality guidelines.

Bowman pointed out that within the bifurcated system of traditional health care, more disruptors are aggressively pursuing value. She suggested that this is the “payment tail wagging the care delivery dog.” She further

SOURCES: Presented by Brynn Bowman on April 27, 2023 (AAMC, 2023; PHI, 2022).

SOURCES: Murphy-Barron et al., 2022. Review of Contract Year 2023 Medicare Advantage expanded supplemental healthcare benefit offerings. Reprinted with permission from Milliman. Presented by Brynn Bowman on April 27, 2023.

pointed out that in a system that provides one set of services to one patient but not another depending on who is paying for their health care, it should come as no surprise that this has led to moral distress and burnout for health care workers.

Turning to policy opportunities to support the workforce, Bowman noted that the Palliative Care Hospice Education and Training Act (PCHETA) would expand the pipeline of people getting trained to be hospice and palliative care specialists. First introduced in 2012 with six cosponsors in the Senate and 39 cosponsors in the House of Representatives, PCHETA has been reintroduced six times. Whether this bill passes and is signed into law is now a matter of prioritization, said Bowman. The Patient Quality of Life coalition and advocates in the field continue to push for it, which would provide funding for national education centers to expand the workforce. Bowman also cited the Resident Physician Shortage Reduction Act, which would offer some loan forgiveness for people to train in specialties experiencing shortages.

Bowman pointed out that at the state level, Illinois HB3571, introduced in February 2023,8 would create a community-based hospice and palliative care professional loan repayment system, which would make it easier for people to opt into these jobs. In Minnesota, SF2786 would provide workforce grants for people working in long-term care. “At the state level, there are options for creativity and for innovation around workforce incentives,” said Bowman.

A growing number of states now require clinicians to engage in palliative care–relevant continuing education to keep their licensure: 39 state-specific requirements on opioid prescribing, 20 on general pain and symptom measurement, and 12 on palliative care, memory care, and end-of-life care. At the federal level, the Medication Access and Training Expansion Act of 20219 requires all providers registered with the Drug Enforcement Agency to complete 8 hours of training on opioid or other substance use disorder by the time they submit their next registration submission. This requirement, said Bowman, should raise the tide on safe and appropriate pain management for patients with serious illness and others.

Although the workforce situation seems dire, Bowman highlighted a few bright spots on the horizon. The Biden administration, for example,

___________________

8 Available at https://ilga.gov/legislation/BillStatus.asp?DocTypeID=HB&DocNum=3571&GAID=17&SessionID=112&LegID=148743 (accessed October 10, 2023).

9 Medication Access and Training Expansion Act of 2021, HR 2067. 117th Cong., 1st sess.

has focused on the direct care workforce, and President Biden signed an executive order that includes measures to improve access to long-term care and bolster job protections for those who work in skilled nursing. One provision attempts to tie reimbursement to worker retention rates in skilled nursing facilities. Several states have increased minimum wage requirements for direct care workers or tied wages to experience in the profession (Abbasi, 2022).

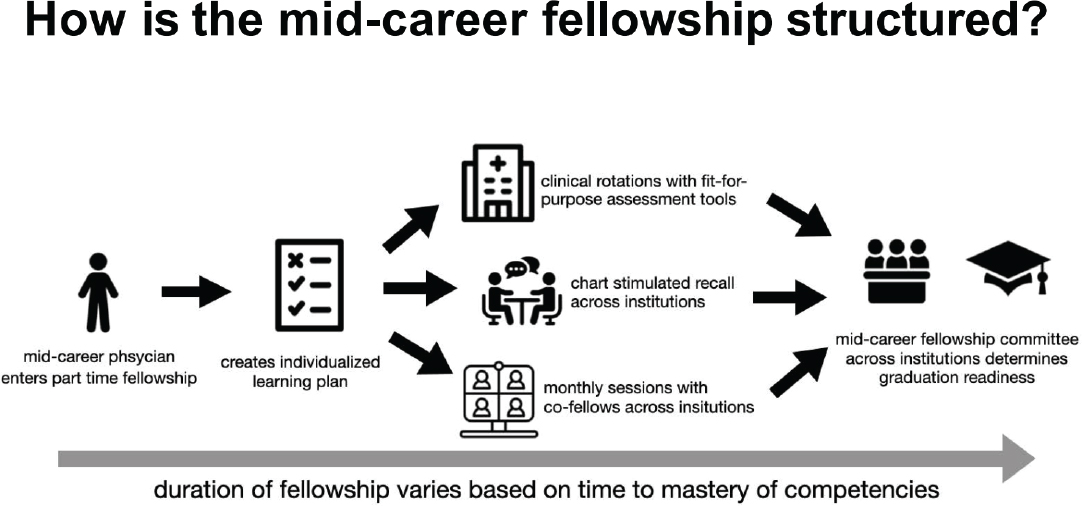

Bowman also pointed out that the University of Pennsylvania has a program that uses a new training model to expand the midcareer palliative care pipeline. This program allows midcareer physicians to complete a competency-based, rather than a time-based, fellowship. This program required the university to get an exemption from the American Board of Internal Medicine. Bowman noted that several states are piloting this program.

Although this is not specific to serious illness care, the health professions are attracting a more diverse group of people, which Bowman said will benefit patients with serious illness. She also noted that health care professionals are demanding better working conditions and better conditions for their patients and in some cases are unionizing (Bowling et al., 2022).

Returning to the framework she proposed for building an optimized workforce to care for people with serious illness, Bowman said none of the six elements are close to being met. As far as what it would take to have an adequate size and mix of disciplines, federal legislation could help widen the pipelines, and local leadership could launch and expand training programs. Diversity is increasing, but Bowman believes it is the responsibility of national organizations focused on palliative care and patients with serious illness to prove to clinicians that this is a good place to work and a welcoming field.

In closing, Bowman emphasized that payment reform is required to have a workforce that is available when and where patients need care, but prioritizing professional well-being does not require expensive investments. “We just have to care,” said Bowman. She shared that what makes her optimistic is that taking steps to support and develop the workforce is feasible. What is required is for bold leadership to look at the health care workforce situation, declare it broken, and then endorse bold solutions to make a difference Bowman concluded.

SYSTEMS-LEVEL APPROACHES TO SUPPORTING THE WELL-BEING OF THE HEALTH WORKFORCE

The third session of the workshop explored the well-being of the workforce caring for people with serious illness. The panelists discussed specific factors that support a happy, healthy, adequately trained, and appropriately prepared workforce. Session moderator Joseph Rotella, chief medical officer at the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, opened the discussion by reflecting back on the first session of the workshop, sharing that he heard a “primal scream” from the brave panelists, which called to mind the visual imagery of Edvard Munch’s famous painting.

Rotella said he often hears the “canary in the coal mine” metaphor when people talk about the well-being of those who provide care for individuals with serious illness. In Rotella’s view, the workforce is represented not by the canary but by the coal miners who spend every day in very dangerous conditions. Rotella pointed out that, unlike a dangerous coal mine, the health care system cannot be shut down.

Highlighting the importance of not blaming health care professionals for being what others may view as insufficiently resilient, Rotella emphasized that “[t]he truth here is that really good, strong people get churned up in this current broken system, and we need to focus not on the victims but really on the system that is failing them.” He referred to Leff’s statement that this work will trigger moral distress and burnout. Rotella himself experienced major burnout well before the pandemic even with all the resources at his disposal. He credited nurses, chaplains, and social workers for getting him through this difficult period in his professional life.

Rotella explained that the National Academy of Medicine’s Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience’s National Plan for Health Workforce Well-Being10 provides a solid framework on which to build efforts to improve clinician well-being. The NAM Collaborative was initiated against the backdrop of rising rates of physician suicide (more than twice as high as that of the general public). Moreover, nearly one-quarter of intensive care unit (ICU) nurses had signs and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (Mealer et al., 2007). The National Plan for Health Workforce Well-Being outlined seven priority areas for health care systems to support the workforce (National Academy of Medicine, 2022):

___________________

10 See https://nam.edu/initiatives/clinician-resilience-and-well-being/national-plan-for-health-workforce-well-being/ (accessed October 10, 2023).

- Create and sustain positive work and learning environments and culture;

- Invest in measurement, assessment, strategies, and research;

- Support mental health and reduce stigma;

- Address compliance, regulatory, and policy barriers for daily work;

- Engage effective technology tools;

- Institutionalize well-being as a long-term value; and

- Recruit and retain a diverse and inclusive health care workforce.

Rotella noted that for organizations that are not ready to take on all seven areas, the consensus is to work on institutionalizing well-being as a long-term value. “Not just because it saves money, not just because we take better care of patients if we are thriving, but because we deserve it,” said Rotella.

Rotella also called attention to the Surgeon General’s Framework for Workplace Mental Health and Well-Being,11 which stresses physical and psychological safety, connection, community to fight loneliness and isolation, work–life harmony, opportunities for growth, and mattering at work. Rotella observed that the last item is about dignity, meaning, and having clinicians realize that they make a difference, concluding that “we can take the whole person approach that we take all the time in palliative care and hospice and apply it to worker well-being.”

Well-Being of the Pediatric Palliative Care Workforce

Rachel Thienprayoon, associate professor of anesthesia and pediatrics and medical director of StarShine Hospice and Palliative Care at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, said that the entire pediatric workforce is caring for children and teenagers with serious illness because the nation is in the midst of an unprecedented mental health crisis in children and teenagers. This crisis has overwhelmed general practice pediatricians, emergency departments, the psychiatric system, and, most of all, parents, many of whom are also clinicians. She noted that the winter of 2022–2023 was terrible in terms of very sick children. Pediatric hospitals were full, and pediatric ICUs nationwide were on diversion status because they were at capacity. Thienprayoon noted that the pediatric workforce is also dealing with gun violence, the leading cause of death among children in the United States.

___________________

11 See https://www.hhs.gov/surgeongeneral/priorities/workplace-well-being/index.html (accessed September 12, 2023).

Thienprayoon noted that there are challenges specific to the pediatric palliative care workforce. As an example, she shared that when she asked these clinicians to name their greatest source of stress and suffering, they said it was the way their colleagues disrespected and devalued them. “It assaults our dignity when a minority of our colleagues do not respect our training and our expertise in the role that we play for families, and we have not grappled with that at this level of the field historically,” she said.

Another source of stress is the tremendous financial strain under which this workforce operates. Thienprayoon noted that the 2018 National Palliative Care Registry survey indicated that 60 percent of pediatric palliative care programs were working beyond their capacity to meet patient needs (Rogers et al., 2021), which still holds today. Working above capacity, she added, is leading to burnout and people leaving the field before it has a chance to grow, creating an ongoing threat to the field.

Thienprayoon explained that compassion means recognizing that another person is suffering, making empathic connections, and acting in a way to relieve that suffering. However, organizational compassion in health care must also account for predictably recurrent sources of suffering for clinicians. She explained that this means measuring and preventing sources of suffering at a systems level, rather than just responding. She noted that the Surgeon General’s model for addressing health care worker burnout at the organizational level is centered on the worker’s voice and equity, with each of the model’s five essential domains based on essential human needs, such as wanting to be valued and having a sense of community and social connection with one’s coworkers. Operationalizing those domains, said Thienprayoon, requires advancing organizational commitment to clinician well-being. She noted that her institution is piloting the Healing Healthcare Initiative developed by the Schwartz Center for Compassionate Healthcare.12 This initiative aims to get organizational leaders involved in clinician wellness at the systems level.

At the team level, research has shown that creating space for debriefing in formal and informal ways is critical to caring for the team, themselves, and others (Leff, 2021). One way her institution focuses on teams is through unit-based Schwartz Rounds.13 “We provide that space for smaller teams to come together and talk about difficult patient situations or just

___________________

12 See https://www.theschwartzcenter.org/hhi/ (accessed September 12, 2023).

13 See https://www.theschwartzcenter.org/programs/schwartz-rounds/ (accessed September 12, 2023).

what we’re talking about here, the stresses of working in health care right now,” said Thienprayoon.

At the individual level, Thienprayoon and some of her colleagues received Stress First Aid14 training, which uses the seven Cs (Nash et al., 2011):

- Check: assess, observe, and listen;

- Coordinate: get help and refer as needed;

- Cover: get to safety immediately;

- Calm: relax, slow down, and refocus;

- Connect: get support from others;

- Competence: restore effectiveness; and

- Confidence: restore self-esteem and hope.

Thienprayoon said the goal is to instill this model throughout the institution’s culture over the next several years. The hope is this will encourage clinical staff to check on one another throughout a normal workday and have the tools to respond in a way that is helpful in stressful times.

Well-Being of the Nursing Workforce

Ernest Grant, immediate past president of the American Nurses Association (ANA) and interim vice dean for diversity, equity, and inclusion at Duke University School of Nursing, referred to the shortage of health care personnel and other limited resources during the pandemic, and asked where those who remain in the workforce can turn for help. He noted the experiences Francis recounted in the first session are what every U.S. health care worker is experiencing today, regardless of the care setting. “Are we using our resources in the right way to help support these individuals or is there something else that we need to do?” asked Grant.

One challenge to addressing staff shortages is attracting and retaining a diverse group of clinicians, particularly young ones. “We need to get younger people and more diverse people to consider a career in health, and the old models that we have been using to try to attract them are failing,” said Grant. With a shortage of approximately half a million nurses, nursing schools are only graduating some 250,000 a year, and not all of them

___________________

14 See https://www.theschwartzcenter.org/programs/stress-first-aid-landingpage/ (accessed September 12, 2023).

will pass the National Council of State Boards of Nursing licensing exam. Further exacerbating the workforce shortage is the fact that nurses and nursing assistants are leaving the field to find more lucrative jobs.

Grant also pointed to the need for employers to provide resources that address the physical and psychological impact on health care team members. He wondered whether employers are listening to what their workforces are saying regarding what they need in terms of support. “The days of the old pizza party, the donuts, the pat on the back, those are long gone,” said Grant, referring to steps health care systems used to consider adequate to support their clinical staff. He recounted that he tells chief nursing officers to actively listen to what their employees are telling them, do something about it, and then let staff members know what steps they have taken to address their concerns. “If a person feels that they have been heard, the most important thing is to keep those lines of communication open,” said Grant.

Grant underscored the importance of developing new models of care. For example, many new payment options include nurses as part of room and board, and others on the clinical team can charge independently for the work they do. “There is something wrong with that particular model,” Grant observed, adding that payment models are even making it difficult for advanced practice nurses to practice at the top of their license and use the skills their education has provided them.

Grant explained that during his last 6 months as ANA president, the organization established a workforce task force to begin to address some of these issues. After conducting nationwide listening sessions, ANA identified six priorities for action: (1) create a healthier and safe work environment, in terms of both adequate staffing at all levels and protecting staff from abusive patients and family members; (2) integrate DEI into a broad range of management functions; (3) create flexibility in work schedules and roles; (4) address burnout and moral distress; (5) implement innovative care models that perhaps integrate technology and other innovations that reduce the time clinicians spend documenting care; and (6) improve compensation programs across the organization.

In closing, Grant shared that he wrote a letter to the Secretary of Health and Human Services in September 2021 asking him to declare the nursing shortage a crisis and bring all relevant stakeholders to the table to address short- and long-term solutions. He is still waiting to hear back. “It is time for us to come together at the table and start implementing these [initiatives] instead of just proposing [them],” Grant concluded.

Well-Being of the Long-Term Care Workforce

Bret Stine recently retired as the executive director of the Keswick Multi-Care Center in Baltimore, which includes a 242-bed nursing center, community programs, and wellness services. Stine pointed out the difficulty with the latter two is that they survive on grants, with no easy way to bring in sufficient revenues to cover their services. Stine noted that the center also receives funding from the largest foundation in Maryland devoted to supporting older people, allowing it to develop resources that other long-term care facilities cannot afford and continue operating despite losing money operationally. Stine pointed out that the daily rate at Keswick is $600, and few people save enough money to support themselves in long-term care for even 6 months, let alone 2+ years; it is largely funded by Medicaid and Medicare, which, in Stine’s view has created financial challenges for those running such programs.

Stine explained that the changes in resident acuity require more staff overall and enhanced skill levels among staff. Some residents, for example, may have complex medical conditions that require five people. Stine called for reinstating timed studies to provide an accurate reflection of the time required to care for each resident to determine whether staffing levels are sufficient. He also raised the need to be more creative with scheduling and training. For example, staff have mandatory training they must repeat annually. “I would argue with you that a 10-, 15-, 20-year employee, and those are getting harder to find, does not need to hear the same session on residents’ rights every single year,” noted Stine.

In terms of workforce shortages, Stine noted out that social workers are in short supply in long-term care facilities. Characterizing them as more valuable than ever today, Stine observed that many social workers are leaving long-term care out of frustration with overburdensome regulations or having to serve as quick discharge machines for patients undergoing rehabilitation. On a final note, Stine explained that due to hospital staffing shortages, “patients that should be on palliative care” are being sent to long-term care facilities.

Well-Being of the Clinical Workforce in Rural Areas

Patricia Fogelman, medical director of palliative medicine at Nittany Health/Mount Nittany Medical Center in State College, PA, pointed out that a key aspect of health care in rural areas is that although geographic

coverage space is often broad, population density is often lower. She noted that this means that patients are traveling 1–2 hours to a hospital, whether that is a 30-bed critical access facility or a medical center such as hers. Geographic coverage space also affects organization’s resources. “It is hard to try and do community-based palliative care delivery when nurses may have to travel 200 miles in a day to just see four patients,” she said.

Fogelman explained that when the pandemic began, it became evident that preserving her organization’s four-person palliative care team—herself, two nurse practitioners, and a social worker—was critical. Fogelman did this by shifting to time-limited rotations of 2 weeks in the ICU, which proved to be the sweet spot between 1 week, which was too short to build relationships, and 3 weeks, which was causing burnout. In addition, staff had daily meetings to check in with one another regarding workload and patient case intensity, and if someone was having trouble, someone else would help out. Weekly lunches gave staff time to have longer, more informal interactions and to try to normalize life to some extent. “We could hear about our social worker’s wedding planning or the one nurse practitioner, who was my new hire, had a very sassy 5-year-old that she was happy to entertain us with stories about,” said Fogelman.

Acknowledging the strong opinions both for and against technology, Fogelman stressed that in rural health care settings, it is imperative to leverage whatever can help bring people closer to each other and help families feel connected and engaged. As the pandemic worsened, her hospital had a no visitation policy for those at the end of life that she and her colleagues said was unacceptable. With critical care and medical leaders, they worked out a compromise that allowed 1-hour visits from family members. Fortunately, noted Fogelman, the hospital had sufficient PPE to support that compromise.

Fogelman explained that her team also began providing iPads at the bedside. She initiated a fundraiser on her social media accounts, receiving a donation of 50 iPads from a local Verizon store, and the chief information officer was able to assure existing hospital iPads were in use and available through the COVID units. Her efforts ensured a bedside iPad for every patient in the hospital, and her team started scheduling iPad visits with families. The rationale, Fogelman explained, was to prioritize connections and the humanity that must come first in medicine.

Fogelman explained that interdisciplinary rounds, which included her and a critical care team member, ICU social worker, chaplaincy, and bedside nurse, became standard during the pandemic and served to streamline the

process. “We were able to hit the high notes of each point, each patient, identify what their needs are, and then focus our next couple of hours on those family meetings and things like that,” said Fogelman. With grant funding, Fogelman and the team’s social worker also built a palliative care resource library with materials recommended by the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. The library served as an important repository of supportive resources to patients, caregivers, and even children.

Fogelman said the accomplishment she is most proud of is increasing the awareness of the impact of COVID on all those who work in a health facility. She described how, in partnering with the chaplain, she launched a systemwide COVID support group that meets once a week, including nurses, food service workers, and those workers who keep the facility running. “I think we lost perspective for a little bit about how deeply [the pandemic] affects all of the members of the health care team,” said Fogelman.

Panel Discussion

Rotella opened the panel discussion with the observation that he found himself connecting the dots between the well-being of clinicians and taking good care of patients. “If you want clinicians to be happy, make sure you are taking good care of their patients,” remarked Rotella. “If you want CNAs to feel rewarded, make sure that if it takes five CNAs to take care of a patient, that there are five CNAs.” Fogelman agreed and said that whole-person care does not start and stop with the patient but extends to the entire system of caring around them. Stine mentioned a need for more refined training for health care workers on ways to be more empathetic and sensitive, and deal with conflict, given that patients are not always at their best. Providing that training helps staff morale and helps health care workers develop a stronger bond with the people for whom they are caring.

Fogelman commented that most students are not receiving this type of training, so new hires do not have a framework or the knowledge to guide them. Her organization is implementing such training in palliative care and basic communication skills. This is very important, she explained, because failing to equip the people who spend the most time at the bedside—nurses and other care partners—with these skills and some empowerment means that they will not function well, which will lead to patient dissatisfaction with care.

Rotella pointed out another key theme was the importance of human connection. For example, while “sympathy pizza [parties]” are not the solu-

tion to boosting employee well-being, staff gathering routinely for lunch was effective. Similarly, acquiring iPads was not magic, but using them to foster human connection was. He asked panelists to expound on how they infuse humanity into their daily workflow, whether as an individual, team, or organization. Grant replied by citing Madeleine Leininger’s culture of caring theory, which emphasizes that culture and caring are essential concepts in nursing (Busher Betancourt, 2015; Lancellotti, 2008) and that if one is to be involved with the patient or community, they must be part of the community. In addition to having a caring culture, it is important to have a culture where everyone’s needs and thoughts are appreciated and addressed when moving forward as a team. “It’s like an all-for-one and one-for-all type of a situation,” explained Grant.

Thienprayoon said she worries that medical training for both physicians and nurses can be dehumanizing. She recounted how she was surprised when her brother, a radiology resident, sent pictures of him holding his newborn son, given the culture of medical training demands that residents go right back to work. In her view, medical training strips away compassion and isolates one’s identity as a physician, pharmacist, or nurse in a way that when that identity is threatened, it threatens one’s core as a human. “We cannot show up for patients if we do not feel like full human beings,” cautioned Thienprayoon.

Stine shared that his organization initiated a committee for culture change and found it to be difficult work. A survey the committee conducted found that staff loved the way the organization handled COVID-19 and felt safe but did not think that management listened to or cared about them until the pandemic struck. The most important finding from that survey was that despite the challenges the pandemic triggered and the burnout that accompanied it, almost 100 percent of the staff reported that they felt that what they do is important. Input from feedback groups provided a glimpse of the staff’s social challenges, so the organization partnered with the Dwyer Foundation, which provides wraparound services for people whose social disadvantages prevent them from coming to work. For example, a staff member’s abusive boyfriend broke her home’s door down, damaging the hinges, and she did not want to leave her children. The foundation sent a carpenter who installed a new door and lock.

Rotella asked the panelists how they create significant change when they are not in a top leadership position. Fogelman said she has learned that it is better to ask for forgiveness rather than permission. In keeping with that lesson, Fogelman—without consulting her organization’s leadership—

pulled together a three-person team to provide a quicker, more agile response to patient needs. She also noted that her organization’s systemwide support group got started because of what she was seeing in her day-to-day interactions. The key point is to consider ways in which to make an impact or solve a problem and then act.

Thienprayoon explained that she launched several activities to affect clinician experience and was exhausted from the efforts and felt she was not making significant progress. “It is hard to advocate from the middle or not from the top,” she said. Importantly, in the wake of her exhaustion, colleagues picked up the torch and applied to be a pilot site for the Healing Healthcare Initiative. Thienprayoon argued that the approach should be to do what one can but to protect oneself at the same time. She also noted how stories from individual staff members can make a profound difference, though it often takes patience to see signs of change.

Stine emphasized the importance of leadership getting to know each staff member as an individual person beyond their professional role and how that contributed to staff feeling more connected. He also stressed that it is critical to take time to explain to those whom the change will affect why it matters. For Grant, this comes down to actively listening and keeping the lines of communication open, to take the time to explain why doing things in a certain way is important. Thienprayoon added that system leaders deserve compassion, too.

Fogelman commented that acts of kindness function like “doses of spiritual care,” so any way to bring that idea into one’s daily activities will be helpful for sustaining well-being. She recalled how she had a partner in pulmonary critical care who thanked every single person as she would walk out of the hospital, regardless of who they were. When asked why she did this, she replied that every coworker needs to know what she sees in them, what she values in them, and that she appreciates the job they are doing. Fogelman said that was such a profound message that she now makes a point of doing the same thing. Similarly, Grant recalled that the CEO of a hospital system he worked at would make rounds day and night and ask staff how they and their family were doing. Everyone who worked at the hospital, regardless of position, felt they could talk with the CEO.

Rotella, referring to Thienprayoon’s statement about the need to change medical education, agreed there is too much “hero narrative” in training, with the hero being the person who takes 10 admissions at night and then goes to the operating room and sews up an aortic dissection, only to be right back to admitting people. The hero, he noted, is never the person who takes

a mental health day. Given that, he asked the panel for their ideas on how to deal with cultural programming that makes people feel like a failure if they take care of themselves. Thienprayoon responded that leaders should model healthy behavior and set a tone that their organization supports staff self-care efforts, and people must model that behavior to one another and give each other permission to be more than a doctor or nurse.

Grant shared the belief that sometimes one must save oneself from oneself. “You do have to give yourself permission to do that, otherwise moral distress and everything else just piles on, and it affects you not only physically but psychologically as well,” explained Grant. “We are not doing ourselves or those that we care for any good when we do not pay attention or listen to our body.” It is important to not feel that one is letting others down when taking care of oneself.

Stine agreed, saying it is key for leaders to demonstrate that behavior. “We do not do enough to encourage our staff to take time off because we are constantly battling with the schedule, but burned-out people cannot do their job. Tired people can’t,” said Stine. He added that he finds it interesting that truck drivers are regulated regarding the miles or hours they can work, but health care workers are expected to work 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

Rotella asked the panelists what they would do if they had a magic wand to make one thing happen immediately and one thing that would be a first step in the right direction. Fogelman said she would implement palliative care education into undergraduate curricula across disciplines to ensure that graduates had at least the basic tenets. Her first step would be to build palliative care training modules for physicians and advanced practice providers and implement a curriculum for her institution’s family medicine and internal medicine residency program and nursing internship program.

Stine noted that he would improve morale and satisfaction by supporting family members having a difficult time dealing with the inevitable. Going forward, he noted the need for palliative care teams to address religious and ethnic and cultural issues when working with families given the nation’s increasingly diverse population. Stine noted that education is key to having happier staff who will stay in the field. Grant said his magic wand would restructure health care so that everyone had equal access to palliative care. Thienprayoon said she would put the patient back in the center of the clinical experience, which requires decreasing the time clinicians are required to spend in the electronic health record.

Audience Q & A

Kashelle Lockman, a palliative care pharmacy specialist at the University of Iowa College of Pharmacy, noted that although community pharmacists provide palliative care to people living with serious illness, most palliative care teams do not yet include pharmacists, despite research indicating that doing so improves the quality of care (Cortis et al., 2013; Malotte et al., 2021). She added that 26 percent of the 35 pharmacy residency positions in palliative care and pain management did not fill all of their open slots in 2022, and burnout may be part of the reason. Coordinating medication across providers is an important role for community pharmacists and contributes to burnout, which will affect access to care, particularly in rural areas.

Lockman asked the panel for thoughts on what can be done as an interprofessional coalition to solve the problem of burnout. Rotella replied that the National Academy of Medicine’s Action Collaborative is a crosscutting group that includes pharmacy organizations as active members. “In that particular collaborative, the voice of pharmacy was as strong as any other,” said Rotella. Thienprayoon said the Pediatric Palliative Care Task Force includes pharmacists among its interdisciplinary members. It is considering conducting a field-level burnout survey that would include all professionals who care for children with serious illness. The goal would be to feed the results to professional organizations, including those for pharmacists, to help them develop the right interventions to support each different role on the palliative care team.

Reifsnyder asked the panelists for the actions they would recommend if they had the ear of their organization’s CEO. Fogelman said she suggested to the leadership of her organization during the pandemic that it offer a meal that staff could take home at the end of their shift to eliminate one thing that they have to do after a long day at work. Stine said his organization does the same thing. To alleviate shortages, he would suggest offering vocational training and reaching into high schools to promote interest among students in joining the field.

Grant remarked that if he had access to organizational leadership, he would bring a list of problems and possible solutions, which he hopes would open a dialogue that could lead to action. Thienprayoon said she published a piece about being burned out, and it quickly found its way to her organization’s leaders, who contacted her to see if she was all right. “That reminded me that I was cared about as a human being,” she said. The