The State of the U.S. Biomedical and Health Research Enterprise: Strategies for Achieving a Healthier America (2024)

Chapter: 4 A Renewed Focus on Health Equity

4

A RENEWED FOCUS ON HEALTH EQUITY

The vision of the U.S. biomedical research enterprise at its inception was to improve health for all Americans—it has not yet achieved that goal. Despite massive breakthroughs in chronic diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, and HIV/AIDS, these and other diseases still impact some populations more severely than others. Racial and ethnic minority groups in the United States, specifically, experience worse outcomes in almost every measure of health and wellness compared to their White counterparts (CDC, 2023). The authors of this Special Publication argue that the U.S. biomedical research enterprise has downplayed the importance of health equity for too long, and it is now time for health equity to be centered in U.S. biomedical research, the workforce that conducts this research, and the enterprise itself.

NOT EVERYONE IS RECEIVING THE BENEFITS OF THE U.S. BIOMEDICAL RESEARCH ENTERPRISE

This section of the Special Publication mirrors the successes outlined in Chapter 2 but highlights existing and growing disparities despite hard-earned advances. This close examination of individual outcomes should help to illuminate the dire need for a comprehensive and sustained focus on advancing health equity in biomedical research.

Disparities in Cancer

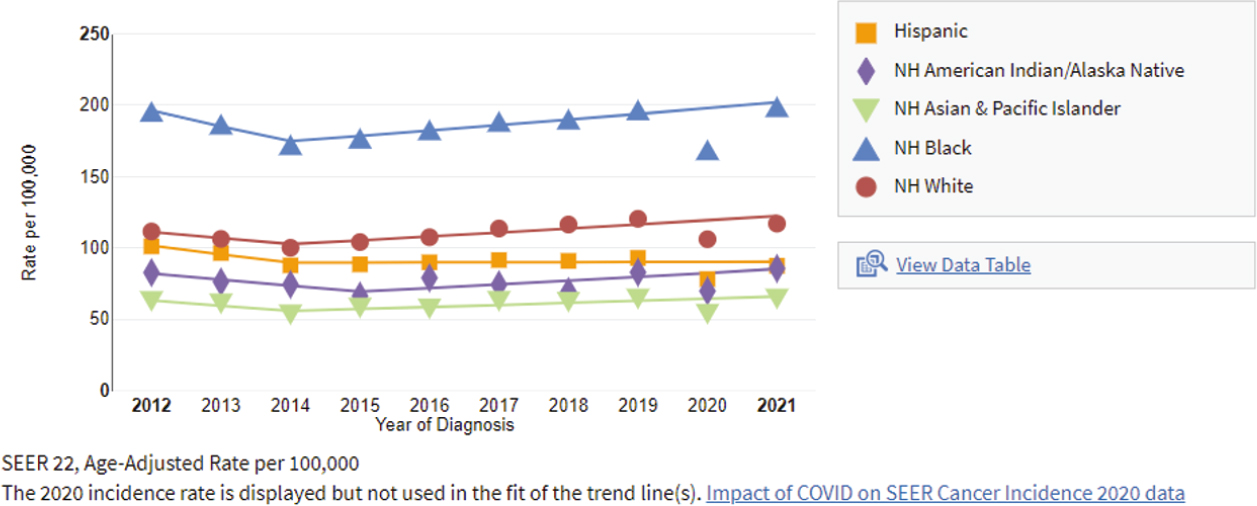

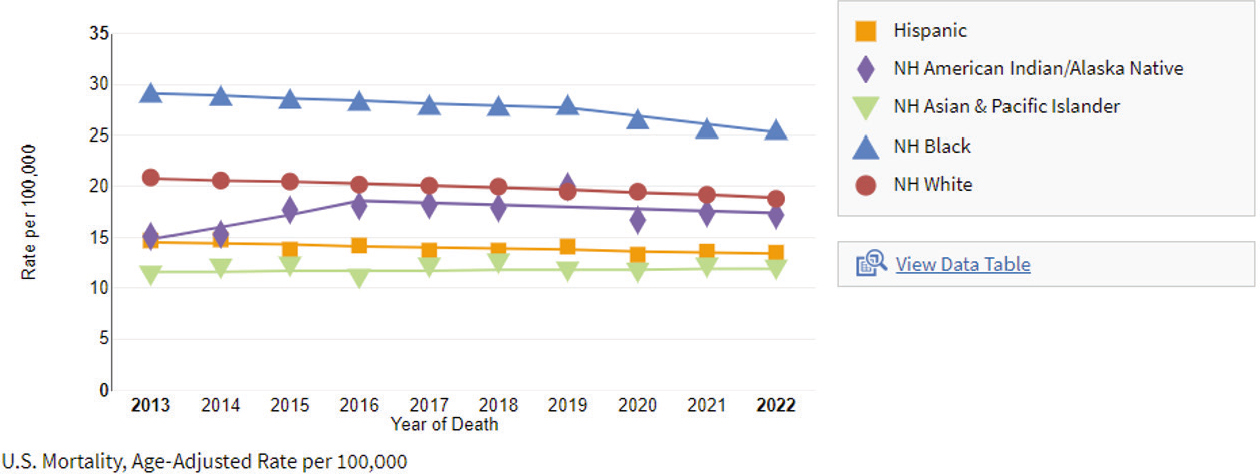

Despite many successes in reducing cancer mortality in the past 20 years, an in-depth look reveals a more nuanced reality. When age-adjusted per 100,000 people and disaggregated by race and ethnicity, the groups experiencing the highest rates of new cancer diagnoses in 2017–2021 were non-Hispanic

White, non-Hispanic Black, and non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native, in descending order from highest rates to lowest rates (NIH NCI, n.d.c). However, during the same period, the groups experiencing the highest death rates due to cancer were non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native, and non-Hispanic White individuals, also in descending order from highest rates to lowest rates (NIH NCI, n.d.c). “For all cancers combined, non-Hispanic Black men have the highest rate of new cancer diagnoses” and experience the highest death rates due to cancer of any racial group (NIH NCI, n.d.c). The prevalence of prostate cancer among non-Hispanic Black men is particularly stark (see Figure 4-1).

“For all cancers combined, non-Hispanic White women have the highest rate of new cancer diagnoses” but non-Hispanic Black women have the highest mortality rate for all cancers combined (NIH NCI, n.d.c). Mortality due to breast cancer has generally decreased, but Black women experience significantly higher mortality rates due to breast cancer than any other group (see Figure 4-2).

Today, 72 National Cancer Institute (NCI)-designated centers across the United States perform cancer research and conduct clinical trials to test new treatments and train the next generation of researchers and clinicians (NIH NCI, 2024).

Disparities in Cardiovascular Health

Despite an overall decrease in cardiovascular disease mortality in the past few decades, disparities have increased. One analysis of cardiovascular mortality between 1967 and 2013 finds that although Black individuals experienced 12% higher mortality due to cardiovascular disease than White individuals in 1969, by 2007 the gap had widened to 38% (Singh et al., 2015). Between 1969 and 2011, mortality rates from cardiovascular disease declined for all groups, but mortality decreased most rapidly among the most affluent individuals (Singh et al., 2015). Individuals from lower socioeconomic strata also experienced higher mortality rates than their peers (Singh et al., 2015). Another analysis revealed that people with low education attainment and low income had a higher risk of cardiovascular disease mortality than those with high education attainment and high income (Khan et al., 2024).

After 2012, increases in heart failure mortality have reversed the downward trend in cardiovascular disease–related mortality by 103%, with the greatest reversals seen in people younger than age 45, people aged 45–64, men, non-Hispanic Black individuals, people living in rural areas, people living in the Southern United States, and people living in the Midwestern United States (Sayed et al., 2024).

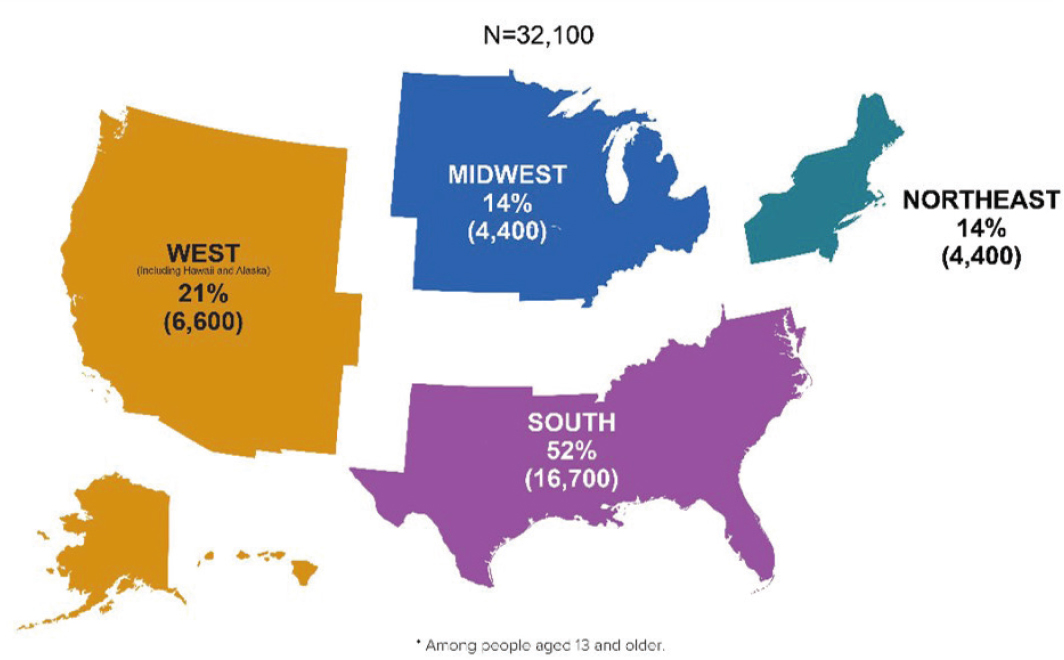

Disparities in HIV/AIDS

Today, more than half of U.S. individuals living with HIV are older than age 50 (HIV.gov, 2023a). Most individuals in this cohort were likely infected when they were younger and have survived to this age because only one in six HIV diagnoses in 2021 were in individuals older than age 50 (HIV.gov, 2023a). Despite a marked reduction in overall incidence and mortality since 1995 due to the availability and use of antiretroviral drugs, between 2009 and 2018, new HIV diagnoses increased in people aged 25–34 and Hispanic men who have sex with men (NIH, 2021). In 2018, 52% of new cases occurred in the American South, where only 37% of Americans reside (see Figure 4-3). In 2021, Black individuals accounted for 40% of new HIV diagnoses in people aged 13 or older, but Black individuals in this age range compose only 12% of the U.S. population (HIV.gov, 2023b). In the same year, Hispanic/Latino patients accounted for 25% of people with HIV but compose only 18% of the U.S. population (HIV.gov, 2023b).

Disparities in Obesity

People of minority race, with lower income, with lower education, and living in certain regions of the United States are at higher risk for obesity than their

NOTE: Among people aged 13 and older.

SOURCE: HIV.gov, 2023c.

peers (Fouad et al., 2022). Black individuals have the highest prevalence of obesity among all groups—49.6%—and Black women have higher rates of obesity than Black men, at 56.9% (Fouad et al., 2022). Geographic disparities are also apparent, as individuals who live in the American South and rural communities are at higher risk for obesity than their peers (Fouad et al., 2022). As mentioned throughout this Special Publication, individuals with obesity are at higher risk for developing diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease, and individuals who experience health disparities related to obesity are also more likely to experience health disparities in these associated conditions, compounding the potential morbidity and mortality from both.

A new class of drugs originally approved for diabetes treatment has begun to be widely used for weight loss. These drugs, six of which have been approved in the United States, can contribute to a 5% to 10% loss in overall body weight (FDA, 2023). However, these drugs are expensive and not always covered by insurance. Even more, prices for these drugs are significantly higher in the United States than in peer nations. An analysis by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that two popular drugs, Ozempic and Wegovy, are five times and four times more expensive in the United States than in Japan and Germany, respectively (Amin et al., 2023). These drugs will likely not be available as more affordable generics for many years, which makes this new intervention effectively inaccessible to many who might benefit from it.

Disparities Among Genders

Individuals who identify as men and women are differentially affected by certain conditions due to factors such as “genetic vulnerabilities to illness, reproductive and hormonal factors, and differences in physiological characteristics” (Vlassoff, 2007). Furthermore, “until recently, a male model of health was used almost exclusively for clinical research, and the findings were generalized to women,” effectively excluding women’s unique risks from clinical research (Vlassoff, 2007). Women are now increasingly included in clinical research, but still not at parity with men, so disparities across the disease spectrum linger. Some examples of these disparities include:

- Men have a 20% higher incidence of cancer than women, and their death rate is 40% higher. However, disparities vary by type of cancer—for example, “thyroid cancer incidence rates are 3-fold higher in women than in men … despite equivalent death rates … largely reflecting sex differences in the ‘epidemic of diagnosis’“ (Siegel et al., 2017).

- About 55,000 more women die from stroke each year than men, and stroke is the third highest cause of death for women (AHA, 2023).

- Women are more commonly affected by alcohol- and drug-induced liver disease and show an increased prevalence of acute liver failure (Guy and Peters, 2013). While men tend to misuse alcohol more than women, the relative risk of alcohol-induced cirrhosis in people who consumed 28–41 beverages per week was found to be 7 in men versus 17 in women (Wieland and Everson, 2018).

Health disparities can also compound, existing along both gender and racial/ ethnic lines. For example, Black men, compared to all other races, are twice as likely to die from prostate cancer (Lowder et al., 2022). Black women have a higher prevalence of heart disease, stroke, cancer, diabetes, obesity, and maternal mortality than their White counterparts (Chinn et al., 2021).

Black women also have worse cardiovascular health than women of all other groups and experience shorter life expectancy than their White counterparts (Chinn et al., 2021). Black women are three times as likely to die during pregnancy and within 1 year of delivery than their White and Latina counterparts, a disparity that has increased over time (Chinn et al., 2021). Chinn and colleagues note, importantly, “Health outcomes do not occur independent of the social conditions in which they exist,” underscoring the need for a comprehensive and sustained approach to health equity within the U.S. biomedical research enterprise (Chinn et al., 2021).

A DIVERSE U.S. BIOMEDICAL RESEARCH ENTERPRISE IS NECESSARY TO PROMOTE HEALTH EQUITY

Data clearly show that diverse teams, especially in science and medicine, lead to improved outcomes for patients, including their “access to care, their perceptions of the care they receive, and their health outcomes, especially for patients of color” (Zephyrin et al., 2023). Beyond directly treating patients, a diverse U.S. biomedical research enterprise workforce is necessary for conducting research to support new initiatives to reduce and ameliorate health disparities and promote health equity. A diverse workforce will help ensure the surfacing of important problems for racial and ethnic minorities that may be otherwise overlooked or ignored by a primarily White workforce; can help build trust in science among the American public; and can help ensure increased participation in clinical trials, thereby generating more detailed data that represents what the American public actually looks like. However, “certain racial/ethnic groups (Black, Hispanic, Native American/Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander individuals), women, individuals with disabilities, and socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals are

persistently underrepresented in the research workforce” (Valantine and Collins, 2015). According to 2021 data, the U.S. biomedical research enterprise workforce is 53.5% White, 26.4% Asian, 9.5% Hispanic or Latino, 6.3% Black or African American, 4.1% unknown, and 0.2% American Indian or Alaska Native (Zippia, 2024). Diversifying the biomedical research enterprise workforce is not only morally right in that it will ensure equal access to jobs in biomedical research for all Americans but will also improve health outcomes for Americans, make research more robust, and advance health equity.

A promising opportunity for diversifying the U.S. biomedical research enterprise workforce pipeline is described in a 2019 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine consensus study titled Minority Serving Institutions: America’s Underutilized Resource for Strengthening the STEM Workforce (NASEM, 2019b). According to this report, the 700 minority-serving institutions (MSIs) of higher education in the United States enroll nearly 5 million students, which represents about 30% of the U.S. undergraduate population (NASEM, 2019b). Proportionally more undergraduate students are majoring in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields at 4-year MSIs compared to 4-year non-MSIs (NASEM, 2019b). The report also states that 25% of U.S. STEM undergraduate degrees are conferred by MSIs—a statistic that is not reflected in the data presented above regarding the composition of the biomedical research workforce, suggesting that students graduating from MSIs with STEM degrees are “leaking” from the pipeline between graduation and employment (NASEM, 2019b). The report recommends stronger policies and practices to “intentionally support nontraditional student bodies, particularly those in STEM fields, who may need additional academic, financial, and social support and flexibility given the unique demands and rigor of these fields” (NASEM, 2019b). The high number of American students graduating with STEM degrees from MSIs presents an immediate opportunity to diversify and strengthen the U.S. biomedical research workforce. Readers should refer to Chapter 6 for additional innovative approaches to recruiting and retaining individuals in the biomedical research enterprise, which could include enhanced student loan forgiveness, clearly defined pathways to becoming a principal investigator, and improved postdoctorate positions that include full employment and benefits.

HEALTH EQUITY MUST BE EMBEDDED INTO THE U.S. RESEARCH ENTERPRISE

As the U.S. biomedical research enterprise has been majority White and male for much of its existence, systemic barriers within the enterprise are standing in

the way of reducing health disparities and improving health equity. These barriers, outlined below, must be addressed and removed for the enterprise to effectively and appropriately center health equity in its work.

Data Are Not Diverse and Can Be Biased

Researchers have been calculating polygenic risk scores—a predictive likelihood of developing certain diseases—since 2007 (Cross et al., 2022). However, until recently, these scores were based on the original reference genomes used in the Human Genome Project, which came from only 12 donors all located in Buffalo, New York (NIH NHGRI, 2024). In fact, according to NIH, greater than 90% of the participants in genomic studies have been of European ancestry before the publication of the All of Us data set in early 2024 (NIH, 2024b). Successful precision medicine requires broad participation across all subpopulations to ensure the availability of data that are representative of every American. These representative data are necessary for generalizing data and applying these data to drug, therapeutic, and diagnostic development, and will hopefully assist in avoiding unforeseen circumstances when a specific subpopulation reacts differently to an intervention because the population at risk was not included in the original research. Progress is being made, but more research is needed to strengthen predictive power for all people. For example, in early February 2024, analyzing the genomes of 250,000 participants, including 50% who were of non-European ancestry, All of Us announced the identification of more than 275 million previously unknown genetic variants (NIH, 2024b). These breakthroughs are both critical and long overdue, and diverse data sets must be prioritized moving forward.

Another challenge to comprehensively addressing health equity is the inherent bias in artificial intelligence, now used more and more regularly in health care and biomedical research. Emerging artificial intelligence and machine learning tools are trained on historical data, which could perpetuate existing biases (Manyika et al., 2019). Some examples of bias inherent in training sets include over- or underrepresentation of subpopulations within a data set, bias built into the data set from the scientists who manage it, or an overreliance on single factors such as vocabulary or income (IBM, 2023). Moving forward, tools should be trained on new or real-world patient data to ensure that historic and systemic bias is not perpetuated, and data engineers should be educated on how to ameliorate or eliminate bias in their data sets. Taking too long to address these issues could lead to decreased public trust in artificial intelligence or machine learning tools when public trust in science is already a challenge (see Chapter 2).

One of the largest challenges in identifying and studying health disparities is the need for appropriate and granular data disaggregation because no average patient exists. Likewise, when using racial identifiers as “buckets” for sorting data, disaggregating into ancestral subgroups will likely be the most relevant and accurate way to understand these data, because race/ethnicity is often an assigned label and ancestry captures the genetic origin of one’s population (Borrell et al., 2021). Efforts such as the National Commission to Transform Public Health Data Systems, launched by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, are only the beginning of the effort to modernize data collection (RWJF, 2021). Federal data collection follows Office of Management and Budget (OMB) definitions, which include only seven categories for race or ethnicity (The White House, 2024). Even so, during the COVID-19 pandemic, many states failed to follow even OMB’s minimal requirements, with some mis-aggregating Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders with Asian individuals, and some not reporting on Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders at all (Kauh, 2021). Although current OMB standards are minimal, agencies need to accurately follow them to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the health of U.S. populations. Further data disaggregation that captures the lived experiences of the entire U.S. population will provide significant insight into misunderstood or misdiagnosed diseases, as well as possible solutions for pernicious health inequities.

A SECOND VALLEY OF DEATH: CLOSING THE LAST MILE

Individuals familiar with the U.S. biomedical research enterprise are likely also familiar with the “funding valley of death” discussed in Chapter 3, or the substantial challenges associated with bringing promising research from concept to market—specifically, procuring funding for this critical but often unprofitable interstitial stage. The authors of this Special Publication believe that a second valley of death, focused on health equity, exists and must be addressed with equal urgency and attention—closing the last mile.

Closing the last mile means getting to people who are hardest to reach, whether due to physical distance or other forms of separation or isolation. The last mile in health care refers to the challenges around providing comprehensive and culturally appropriate health care to marginalized groups; racial and ethnic minorities; Indigenous communities; and people with challenges including disabilities, lack of health insurance, illness, or lack of access to transportation. Many systemic factors contribute to the persistence of the last mile in health care, which further exacerbates health disparities. In addition to being the “farthest from care,” individuals impacted by the last mile are also likely those about which

the least is known. To achieve health equity in the United States, we must fully research, understand, and mitigate the barriers that sustain the last mile.

In the developing world, the last mile often describes a lack of roads, dirt roads accessible only by foot, and roads that are only seasonally accessible because of flooding or other environmental and climate cycles. In the United States, the last mile in health care likewise separates vulnerable populations from health care services, although by different barriers.

The last mile exists in both rural and urban areas. In rural areas, distance from hospitals that provide specialty care, a lack of local health care facilities or providers, a lack of adequate or any health insurance, and limited or no access to high-speed internet isolate individuals from services. In urban areas, a lack of adequate transportation, crime, or poverty are barriers to accessing health care. Across both urban and rural environments, the last mile exists anywhere individuals experience racism, sexism, or other discrimination that keeps them from seeking care, and is exacerbated by a historical lack of trust in science, health care, and practitioners of both. In addition, people who live in the last mile are typically the most vulnerable members of society, and their circumstances are worsened by a lack of access to adequate health care.

The implications of the last mile are multitudinous but include that 63% of U.S. counties—71% of which are rural—are designated “primary care health professional shortage areas” by the Health Resources and Services Administration (AHRQ, 2023). The digital divide, or the unequal distribution of both technology and technology literacy, impacts rural, low-income, and older individuals most sharply, as “only 55% of U.S. adults over 65 own a smartphone or have home broadband access,” only 71% of individuals living below the poverty line own a smartphone, and one in four individuals living in a rural area say that broadband internet access is “a major problem in their community” (Lyles et al., 2022; Read and Wert, 2022). Older and low-income individuals are more likely to have chronic illnesses requiring frequent management than their younger and higher-income peers, and the digital divide can impede their access to virtual care, just as such forms of care are becoming more and more commonplace (Benavidez, 2024; NCOA, 2023).

Despite expanded access to health care through the Affordable Care Act and to Medicaid and Marketplace plans during the COVID-19 pandemic, in 2022, 25.6 million nonelderly American adults did not have health insurance (Tolbert et al., 2023). Of this population, 64% reported that “they were uninsured because the cost of coverage was too high” (Tolbert et al., 2023). A lack of health insurance directly complicates access to preventative and acute health care. Furthermore, when uninsured individuals do seek care, they are more likely to have medical

bills or medical debt that they cannot pay, placing them at even greater risk for poorer health outcomes (Tolbert et al., 2023).

In every state where data are available, racial and ethnic minorities are shown to experience disproportionately negative health outcomes compared to their White counterparts, and White individuals are more likely to access preventative care than their racial and ethnic minority peers. More specifically, Black and American Indian or Alaska Native individuals are “much more likely to die” from treatable conditions like diabetes-related complications than their counterparts (Radley et al., 2021). White and Asian individuals are more likely than Black, American Indian or Alaska Native, and Latinx/Hispanic individuals to get an annual flu shot, which greatly reduces their risk of potential complications and mortality due to influenza (Brewer et al., 2021). Last but importantly, although the quality of care varies across states, White individuals generally receive better quality health care than Black, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian/Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and Latinx/Hispanic individuals (IOM, 2003).

Even when individuals do seek care, discrimination can discourage them from returning for necessary follow-ups, compel them to spend time seeking a new provider, or cause them to avoid obtaining care altogether, all of which can lead to negative health outcomes (Gonzalez et al., 2021). A study by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation found that Black individuals experience discrimination in health care at three times the rate of White individuals and twice the rate of Latino and Hispanic individuals (Gonzalez et al., 2021). Black women and low-income Black individuals experience even higher rates of discrimination. Given that Black women already experience disparately negative health outcomes, as discussed earlier in this chapter, discrimination that deters or prevents them from seeking or receiving care must be addressed to reduce the disproportionately high rates of morbidity and mortality in this demographic group.

Just as health disparities can and do intersect and exacerbate one another, so can aspects of the last mile. A lack of transportation and a dearth of local health care facilities—aspects of the last mile—can prevent individuals from accessing care. Telehealth and telemedicine services, popularized during COVID-19 and now becoming more and more widely used, appear to be one solution to this problem because individuals can access care from their homes without the need for transportation or to travel hundreds of miles to the nearest hospital (Gelburd, 2023). However, populations that require easier access to care increasingly overlap with those that lack access to high-speed internet or a smartphone, rendering virtual care just as difficult to access as in-person care. One potential solution to this pernicious problem is providing care outside of the hospital or clinic, as many “hospital at home” programs piloted across the country have endeavored to

do (Noguchi, 2023a). Additional research is needed to confirm the efficacy and safety of such programs, as well as their ability to scale, but they offer promise for reaching people affected by the last mile.

The authors of this Special Publication have defined the health equity valley of death as such to call attention to this critical, complex, and overlapping set of structural barriers that keep the most vulnerable individuals in the United States from accessing safe, effective, and culturally appropriate care. Sustained attention and research are needed to close the last mile and to ensure, in doing so, that unintended consequences are minimized and the needs of those most impacted by the last mile are centered.

Efforts to address the health equity valley of death will focus on the portion of biomedical research translation that occurs after the funding valley of death. Once a piece of research has been successfully translated into a therapeutic, diagnostic, or medical device, the health equity valley of death obstructs the delivery of these products to people who need them most. Closing the last mile will ensure the effective deployment and delivery of products that were successfully translated from research. The world learned well during the COVID-19 pandemic that an efficacious vaccine does nothing to prevent the spread of disease until it is injected into someone’s arm—closing the last mile will ensure that the fruits of the U.S. biomedical research enterprise are available to people who need them—no matter what they look like, where they are located, or how much money they have.

CALL TO ACTION

As the nation reimagines the possibilities of the U.S. biomedical research enterprise, it is critical—and long overdue—to ensure that achieving health equity and reducing health disparities are key goals. To achieve its full potential, the enterprise must be able to share its achievements with all Americans, regardless of race, gender, socioeconomic status, or any other factor. Health inequities are pernicious and complex, but if any enterprise can address them, it should be the U.S. biomedical research enterprise. To achieve this vision, the authors of this Special Publication propose the following:

Priority 3-1: Federal prioritization of research that informs solutions for achieving health equity in the United States, including those focused on the social determinants of health, diversifying the workforce, and the U.S. biomedical research enterprise itself. These research areas could include:

- Increasing trust in medicine, science, and the U.S. biomedical research enterprise itself;

- Mitigating structural and systemic discrimination;

- Delivering care to patients and the communities where they reside, using advances in implementation science to guide these solutions;

- Improving the communication of scientific and medical information; and

- Bolstering community engagement and effective bidirectional dialogue.

Priority 3-2: Federal prioritization of research on the “health equity valley of death”—closing the last mile—to understand and eliminate barriers that are preventing the most vulnerable populations in the United States from receiving and accessing comprehensive, high-quality, culturally appropriate care. Specific research areas could include:

- The digital divide;

- Improving access to health care, specifically for individuals who cannot afford adequate or any insurance coverage;

- Transportation barriers;

- “Health care deserts,” or a lack of health care providers—primary and specialty—in a given geographic area;

- Improving trust in science, medicine, and practitioners of both;

- Providing care outside of clinics and hospitals to meet individuals where they are; and

- Reducing racism, sexism, and other discriminatory practices that may keep individuals from seeking care.