Forecasting the Ocean: The 2025–2035 Decade of Ocean Science (2025)

Chapter: 3 Opportunities and Strategies for Accelerating Progress in Ocean Science

3

Opportunities and Strategies for Accelerating Progress in Ocean Science

In addition to developing “a concise portfolio of compelling, high-priority, scientific questions,” the statement of task asked the committee to “identify opportunities and strategies to promote innovative multidisciplinary and multi-sectoral approaches” to address these science challenges (see Box 1.2 in Chapter 1). In response to this task, the committee developed a framework for accelerating progress in the field of ocean science rooted in transdisciplinary1 approaches to research, workforce development, and partnerships. The committee champions the continued need for basic research and advocates for a transdisciplinary lens to be utilized in planning and advancing basic research, and applying the research results.

A TRANSDISCIPLINARY COLLABORATIVE FRAMEWORK FOR OCEAN SCIENCES

Natural changes that are physical, biological, geological, or chemical and actively affect the ocean are generated by a wide range of mechanisms and processes known collectively as ocean processes. Ocean processes are integral to the planet’s living and life support systems. Ecosystems at all scales depend on or are affected by all ocean processes. This is also true for humans, who have a deep history of interaction with the ocean (Erlandson, 2001). Much of conventional science research has historically been dualistic—treating humans as fundamentally different and separate from the rest of nature—which can unintentionally limit the researcher’s ability to connect scientific insights on the natural world to human health, society, and culture (Berkes, 2003; Ivakhiv, 2002). While the specific details of societal needs and the role of the ocean in supporting those needs can vary based on social, cultural, political, and historical context, at its core, the overarching objective of public policy is to support and improve the long-term well-being of humans and the planet’s living and life support systems (e.g., Breslow et al., 2016).

A focus on human well-being and its relationship to ocean processes can provide an enduring connection that places the ocean sciences in important multidisciplinary (natural, social, and health sciences) and multisectoral conversations. This approach is key to supporting human well-being by emphasizing the value of ocean science research and solving the global ocean challenges being faced. As such, in the next decade, research that connects ocean processes to human well-being through systems thinking2 and transdisciplinary approaches will constitute an important step towards overcoming the historical human–nature dualist perspective and also engage the field of ocean science with issues of social and cultural importance (Box 3.1).

The path toward conducting successful transdisciplinary ocean science research is partially laid, but it is not easily put into practice. Research areas for which transdisciplinary approaches have already been identified and partially implemented include ocean acidification, marine heat waves, and hypoxia (all discussed in Chapter 2; Yates et al., 2015). For instance, Yates and colleagues (2015) provide a case study of the importance of transdisciplinary science for achieving societally relevant outcomes in ocean acidification research, a chemistry problem that is deeply intertwined with ecosystems and society:

The global nature of ocean acidification (OA) transcends habitats, ecosystems, regions, and science disciplines. The scientific community recognizes that the biggest challenge in improving understanding of how changing OA conditions affect ecosystems, and associated consequences for human soci-

___________________

1 See Box 1.3 in Chapter 1 for the committee’s definition of transdisciplinary research.

2 Systems thinking means considering a system holistically, in this case including humans as a component of the ocean system.

ety, requires integration of experimental, observational, and modeling approaches from many disciplines over a wide range of temporal and spatial scales. Such transdisciplinary science is the next step in providing relevant, meaningful results and optimal guidance to policymakers and coastal managers (p. 213).

BOX 3.1

Transdisciplinary Research for All Communities

Ocean science research and problem-solving in support of human well-being needs to implement scientific approaches that help mitigate the adverse effects of climate change on communities, including those that are most vulnerable. For example, many Pacific Island nations are facing adverse effects of sea level rise, lack of fresh water, extreme storm events, drought, ocean acidification, saltwater intrusion into groundwater, and biodiversity loss (Ober and Waters, 2023). As many communities across the globe are on the front line of climate change, it is now crucial to seek solutions together, with various types of knowledge informing research, forecasting, and ultimately a global change adaptation plan (Figure 3.1; Adger et al., 2006; Jodoin et al., 2021; UN, n.d.).

SOURCE: Per-Anders Pettersson.

Collaborative development of transdisciplinary research, including basic research, is essential to finding innovative solutions to the problems affecting communities on the front lines of climate change. Often, engaging in collaborative production of knowledge and building transdisciplinary teams is challenging, producing unsuccessful results. However, taking the time and effort to conduct and resource successful transdisciplinary research in the next decade is essential for solving these problems.

These collaborative efforts, however, have not yet enabled the full understanding of the complex interactions of multiple stressors on human-caused changes in the ocean and the response to those changes by marine ecosystems. To succeed in understanding these interactions, a culture shift is needed, bringing together multiple knowledge holders (e.g., oceanographers, biotechnologists, the modeling community, business leaders, data scientists, engineers, Indigenous and local knowledge holders, local interest holders, policy makers, educators) to conduct ocean science research and generate predictive models for forecasting ocean and ecosystem change (e.g., Cavaleri Gerhardinger et al., 2024; Garibay-Toussaint et al., 2024). The process of achieving true transdisciplinary and multisector knowledge-building will necessitate that collaborators share responsibility and harmonize priorities throughout the various stages of the research process, from conceptualization of knowledge needs and framing of research questions to information-gathering, interpretation, writing, and dissemination (Christie, 2011; Webster et al., 2022).

Leveraging Multiple Knowledge Systems to Foster Transdisciplinary Collaboration

Traditionally, innovation in ocean sciences has centered on natural scientists, engineers, and industry professionals and has marginalized social scientists, historians, tribal and Indigenous leaders, and community members. However, a transdisciplinary approach requires that everyone with a deep understanding of the topic area be included in the early stages of the research and innovation process. It requires recognizing experience and cultural knowledge as true expertise, on equal terms with formal education in traditional research science. This approach may also expand the way parts of a research project are conducted, moving from precise agendas, timelines, and milestones toward a more interactive, exploratory, discovery-based methodology for combining talents and knowledge (e.g., two-eyed seeing;3 Reid et al., 2021). Furthermore, research teams with strong intercultural competency can help translate critical findings across communities, cultures, and languages, yielding more actionable outcomes. Examples of scientific research collaborations that include transdisciplinary approaches are the National Science Foundation (NSF)-funded Cascadia Coastlines and Peoples Hazards Research Hub4 (2025), a project that incorporates a range of knowledge systems, fostering transdisciplinary science, with the goal of helping “Pacific Northwest coastal communities prepare and adapt to coastal hazards through research and community engagement” (para. 1; see Box 3.2). These programs engage social scientists, modelers, regulatory agencies, educators, and cultural practitioners to explore solutions to pressing issues. As such, through transdisciplinary collaboration, advancements have been made to further an understanding of Earth systems.

As funding organizations seek to support collaborative science, with an emphasis often placed on broader impacts and meaningful community engagement, resources outlining best practices and strategies for achieving meaningful and successful engagement with nonacademic groups are needed. This requires developing collaborative processes that allow research focuses to expand to include community concerns such as well-being, cultural values, and livelihoods, as well as emergent impacts of research activities on local social dynamics. Some guidelines currently exist (Kūlana Noiʻi Working Group, 2021; NOAA, 2022; Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment [PAME], 2019), yet efforts to outline a set of guidelines would promote the success of future transdisciplinary projects.

Systemic Change in Valuation of Transdisciplinary Research

Conducting successful transdisciplinary ocean science research will take dedicated time, effort, and a more collaborative mindset during project inception, development, and output. Transdisciplinary science includes valuing and championing reciprocal relationship-building, implementing dedicated strategies for partnerships, and conceptualizing use-inspired research that includes multiple discipline and knowledge systems. True and effective knowledge co-production requires democratization and decolonization of knowledge-sharing structures. For example, people are more likely to share treasured, cultural knowledge and participate in its application in the research project if they have confidence that their contribution is valued (García-Quijano and Pizzini, 2015). This requires a commitment to cooperative formats and venues that empower oral history and knowledge-sharing rather than asymmetrical formats such as conference presentations or public hearings, which can favor those who command technological tools such as computers, statistical-graphing software, and presentation software.

One challenge to fostering collaboration across knowledge systems and disciplines is rooted in the way academic scientists, funded by NSF and other agencies, are assessed in decisions about attribution, hiring, tenure, and promotion. Many current assessment efforts consider metrics that can be quantified easily, such as number and amount of funded grants, and number and citations of publications; however,

___________________

3 Viewing the world through different perspectives (often referring to combining Indigenous and Western views) to create a new way of seeing.

BOX 3.2

Embracing the Spirit of Cascadia

The Cascadia Coastlines and Peoples (CoPes) Hazards Research Hub encompasses teams of researchers working to improve forecasting and coastal community resilience against natural hazards with a focus on the Pacific Northwest.a The Cascadia coastline is coincident with the Cascadia subduction zone, which extends from Cape Mendocino, California, to Vancouver Island, Canada. Coastal communities in this region face an array of risks, from decadal-scale rising sea levels and changes in weather, to abrupt hazards caused by ground-shaking, landslides, and tsunamis driven by subduction zone earthquakes. Changes in relative sea level along the coast are further exacerbated by tectonic motions associated with the subduction system.

The CoPes Hub brings together scientists and local communities to make transformative improvements to the understanding of coastal hazards (Figure 3.2). Coastal communities in Cascadia boast a wealth of cultural, social, and governance histories, along with traditional and local ecological knowledge. Their identities, values, and economies are deeply rooted in their coastal environments and ecosystems. Through community engagement and co-production, the CoPes Hub seeks to improve the ability of these communities to adapt to coastal geohazards.

SOURCE: Alessandra Burgos, Oregon State University.

The CoPes Hub is organized around five teams: (1) tectonic geohazards; (2) inundation and coastal change hazards; (3) community adaptive capacity; (4) science, technology, engineering, arts, and math (STEAM) education; and (5) community engagement and co-production of coastal hazard knowledge. Work is focused in “collaboratories,” allowing researchers to partner with local communities with varied geologic and ecologic characteristics. Pilot projects from outside the project team are funded annually to support emergent research ideas and engage local communities. Examples of ongoing pilot projects include building multihazard evacuation map prototypes for coastal communities and establishing a community-driven earthquake monitoring program at the Quileute Tribal School. The CoPes Hub also facilitates opportunities for geoscientists to engage with coastal planners, community leaders, emergency managers, and state and federal agencies to discuss how geohazard research can be tailored to meet coastal community needs.

a The CoPes Hub is funded by the National Science Foundation’s Geosciences Division of Research, Innovation, Synergies, and Education.

systemic racial disparities affect funding rates at NSF and likely other research funding bodies (Chen et al., 2022), promoting cascading impacts that perpetuate bias in the types of research conducted, decrease geographical distribution of funds, and negatively impact transdisciplinary workforce development. A related challenge is the lack of appreciation by academic administrators for the extra effort required to promote meaningful engagement of local communities and Indigenous groups, which can also affect publication output and related criteria for promotion. Even though many scientists conduct societally relevant research, few assessments exist that focus on quantifying the ways in which a research project contributes to the greater societal good. Systemic change in evaluation that encourages using all-embracing research practices, including initiatives that promote societal benefit, will enable fulfilment of the vital research goals outlined in this report. These revised evaluation criteria may include fair considerations of authorship and attribution; data management and access; data translation and dissemination; data sharing; use of collective benefit, authority to control, responsibility, and ethics (CARE) principles and findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable (FAIR) principles; and application of metadata labels to protect Indigenous and local knowledge, such as traditional knowledge labels used by the Local Contexts Project.5

Practical Steps to Building Transdisciplinary Ocean Science Research Teams

Building transdisciplinary research teams is a path towards increasing broad participation in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM), promoting co-production with communities, and solving problems that include many interdependent factors and processes. Those conducting ocean science research must first recognize that a collaborative culture is a people-first structure within the overall research enterprise (Sahneh et al., 2021). Building this collaborative culture for successful transdisciplinary ocean science research teams will take time and dedication to (1) establish shared understanding of complex scientific problems and develop shared research goals, (2) co-develop conceptual frameworks and research designs that integrate approaches from multiple fields and perspectives, (3) execute the planned research, and (4) translate research findings to innovative solutions for marine ecosystems and human well-being. For example, the transdisciplinary teams needed to address pressing issues related to the three priority themes emphasized in this report—ocean and climate, ecosystem resilience, and extreme events—are all different and may leverage experts from the computing and technical modeling community, as well as place-based knowledge holders such as subsistence fishers to refine models and research designs.

Environmental and conservation research communities provide many recommendations for avoiding last-minute, shallow engagement with local and transdisciplinary research partners. These include enabling trust-building via low-budget, limited-scope initial projects; lowering barriers to including local partners in the grant application process (Rayadin and Burivalova, 2022); and applying multiple methods of co-producer engagement, such as workshops, community partner advisory groups, participatory mapping, and scenario development (Kliskey et al., 2023). An underutilized resource is university-based extension services that have a mission to translate research-based findings, good practices, and information to address interest-holder needs, including state, industry, and community needs. Extension professionals have long and trusted relationships with the communities that they serve. Their work, when adopted, contributes to the democratic process of knowledge generation as communities and businesses work hand in hand with students and researchers in academia to address local issues. The National Sea Grant College Program, created in 1966 and originally housed in NSF, combines research, education, and outreach to address coastal issues of resource management, academia–industry interactions, environmental quality, and economic competitiveness. Programs such as Sea Grant, as well as community-based private organizations such as The Nature Conservancy or Conservation International, can be leveraged to build trust and engage local communities in transdisciplinary research.

Table 3.1 outlines a framework for building transdisciplinary teams that increases collaboration and aims to address complex scientific challenges and improve human well-being (Hall et al., 2012). NSF’s Division of Ocean Sciences (OCE) could adapt the four-phase model approach, originally applied to the

___________________

health sciences, to offer as guidance to proposers on how to structure transdisciplinary ocean science research teams. Membership of such teams would necessarily include scientists from multiple disciplines and sectors, as well as partners from community groups, in various phases of the research process. Additional research on this topic emphasizes the importance of managing communication among and ensuring accountability of all team members (Waite et al., 2023). Other resources include models of different leadership approaches for small and co-located transdisciplinary teams versus large and disperse teams (Gray, 2008), and insights on how to facilitate and distribute leadership within a large transdisciplinary team to improve collaboration and support transdisciplinary research objectives (Archibald et al., 2023). Additionally, social network analysis offers quantitative and qualitative indicators important in the assessment and evaluation of transdisciplinary research team effectiveness (e.g., Steelman et al., 2021) and for identifying influential actors and information brokers, as well as barriers and opportunities in collaborative networks (Hoelting et al., 2014; Smythe et al., 2014). Lastly, transdisciplinary design features specifically applied to ocean development–financed projects in underresourced settings found that community participation and multiknowledge systems were key to progress (Hills and Maharaj, 2023).

TABLE 3.1 Four Phases of a Transdisciplinary (TD) Team-Based Research Model

| Developmental | Conceptual | Implementation | Translational | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Establish a shared understanding of the scientific or societal problem space of interest—including what concepts fall inside and outside its boundaries—and mission of the group | Develop novel research questions or hypotheses, a conceptual framework, and a research design that integrate and extend approaches from multiple disciplines and fields | Launch, conduct, and refine the planned TD research | Apply research findings to advance progress toward developing innovative solutions to real-world problems, as appropriate and to the level of science at which the research is conducted |

| Team Type(s) |

|

|

|

|

| Key Team Processes |

|

|

|

|

SOURCE: Hall et al., 2012.

CONCLUSION 3.1: Transdisciplinary mindsets, skillsets, and practices—including collaborations with other disciplines such as humanities and social scientists, as well as stewards of Tribal, Indigenous, and other knowledge holders—will be the key to actualizing a new paradigm of ocean science. Multiple perspectives, not only for ocean science researchers but also among ocean science funding agencies and directorates, will advance innovation in applying basic research. Resource investment is needed, both fiscally and programmatically (including in leadership development, management, and outcome assessments), to support and incentivize transdisciplinary research teams to be created and sustained in the field of ocean science.

RECOMMENDATION 3.1: To foster transdisciplinary research that promotes emerging solutions to challenges related to changes in ocean systems and processes, the National Science Foundation’s (NSF) Division of Ocean Sciences should invest in projects that utilize a participatory process toward relationship-building and collaborative efforts, establishing long-term trust and knowledge-sharing and impacting broad interests. NSF should explicitly enable research that crosses directorates and programs and intentionally facilitate efforts to dismantle barriers to transdisciplinary approaches and implementation. Potential strategies include:

- supporting projects with measurable social and environmental returns on investments, especially use-inspired and solutions-oriented research on the changing ocean;

- investing in training an expanded ocean science workforce that includes developing essential science, technology, engineering, and mathematics skills as well as transdisciplinary skills that enable meaningful connections to the humanities, social sciences, and economics;

- implementing requirements for proposals that encourage partnerships with interest holders including local communities, regional organizations, Indigenous and Tribal groups, and other users, to participate in ocean research; and

- financially supporting platforms and networks that facilitate knowledge exchange between interest holders, sectors, and disciplines.

WORKFORCE DEVELOPMENT

Coastal interest holders, particularly historically marginalized communities and underrepresented groups, face daily challenges in comprehending and navigating the intricacies of ocean and coastal governance. Gaining competencies to influence decision-making related to the ocean and coasts necessitates knowledge of historical social and ecological baselines, which are often obscured by limited awareness of marine ecosystems and gaps in intergenerational knowledge transmission. To effectively bridge the imbalances in ocean science capacity and promote public engagement in research, the ocean science enterprise needs to foster strategies and develop competencies that empower ocean stewards in decision-making. It requires including both scientists and nonscientists, especially from historically marginalized communities and underrepresented groups in ocean science research, education, and governance. Gerhardinger et al. (2024) suggests using a combination of marine learning networks (Bayliss-Brown et al., 2020; Dalton et al., 2020) with media and information ocean literacy strategies (Singh et al., 2016) to develop transdisciplinary capacities and engage nonacademic interest holders in co-production of knowledge, thus democratizing the venues and mechanisms for knowledge creation, access, and sharing, with the reconsidered experts as described above, with fair distribution across the globe. Building transdisciplinary capacities also requires sustained commitment and collaboration across multiple disciplines, sectors (public, private, academic) and scales (local, regional, national, international). Incorporating such an approach to ocean science research is important for training the next generation of the ocean science workforce. Box 3.3 describes one program aimed at increasing traditional, local knowledge in ocean sciences and the value this program has added to science, specifically to fisheries and marine science management in Alaska.

A wide array of perspectives and experiences in the ocean sciences workforce will contribute to innovation and is critical to meeting society’s needs. People with different backgrounds, perspectives, and experiences working together leads to more innovative and creative problem-solving (Aminpour et al., 2021). Heterogenous teams can identify a wider range of potential issues and solutions than homogenous teams (Bendor and Page, 2018), and manuscripts from ethnically variant publishing groups have been found to be more impactful than those from homogenous groups (Freeman et al., 2014).

Furthermore, as discussed in the section on transdisciplinary research, broad representation in research improves the relevance of ocean science outcomes. Many coastal and island communities, with deep-rooted, historical–ecological knowledge about their marine environment, are on the front line of experiencing ocean

BOX 3.3

“All of Us”: The Tamamta Program

SOURCE: Orutsararmiut Traditional Native Council, photo courtesy Elizabeth Lindley.

The National Science Foundation Research Traineeship Tamamta program at the University of Alaska Fairbanks uses Indigenous approaches to transform graduate education programs in fisheries and marine science fields, which tend to lack cultural representation in academia and the workforce (Figure 3.3). Named for a Sugpiaq and Yup’ik word meaning “all of us,” the Tamamta program broadens graduate training to engage Indigenous students, to center Indigenous knowledge systems in current and new curricula, and to reach widely across the university and partner organizations toward larger system change.

As environmental and social challenges intensify in the Arctic, the need for bold and transformative action that crosses cultural, racial, and disciplinary boundaries grows. To respond to this need, Tamamta supports comprehensive graduate training that advances science, bridging Western and Indigenous knowledge systems for M.S. and Ph.D. trainees. Program activities include new team-taught interdisciplinary courses, an elder-in-residence program, a visiting Indigenous scholars’ program, a fish camp and other cultural immersion experiences, professional development and cultural competency skill-building with faculty and agency partners, retreats, internships, coastal research experiences, hosted dialogues, and art installations.

Tamamta is dedicated to effective training of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics graduate students in high-priority interdisciplinary and convergent research areas through comprehensive traineeship models that are innovative, evidence-based, and aligned with changing workforce and research needs. The program has reached more than 100 students over the past 5 years and engaged federal, state, and tribal partner organizations toward larger system change within fisheries and marine science and management in Alaska.

changes and yet are underrepresented in ocean science research careers (Kitolelei et al., 2022; Thornton and Scheer, 2012). Increasing collaboration with these communities in ocean research sectors can ensure their needs and knowledge are incorporated, enhancing understanding and making the research more relevant and impactful for all (Fischer et al., 2015; Thornton and Scheer, 2012), while supporting transformative, transdisciplinary and multi-sectoral research that addresses global societal needs and human wellbeing (AlShebli et al., 2018).

There is a crucial need for education and training to develop transdisciplinary mindsets, skills, and leadership abilities among those conducting research. For transdisciplinary ocean science research to truly advance, current and future ocean science researchers need not only foundational disciplinary knowledge, but also additional knowledge and skillsets such as cross-cultural communication, emotional intelligence, and active listening skills, among others. For example, integration of knowledge and expertise across disciplines and communities is identified as a core challenge and the defining characteristic of transdisciplinary

research (Hoffmann et al., 2022), but the traditional, siloed culture in higher education has been slow to transition to more integrated research approaches. There is some evidence of growing momentum toward facilitating greater transdisciplinary habits of mind and skills in undergraduate (Bammer et al., 2023) and graduate programs (Box 3.4; Horn et al., 2024; Kluger and Bartzke, 2020), including some work in marine research management (Ciannelli et al., 2014) and marine science (Wilson et al., 2021). Funding agencies can further catalyze change in ocean science education and research by investing in projects that support and assess the success of transdisciplinary approaches in undergraduate and graduate education and the transfer of knowledge from place-based knowledge holders.

The Current State of the Ocean Science Workforce

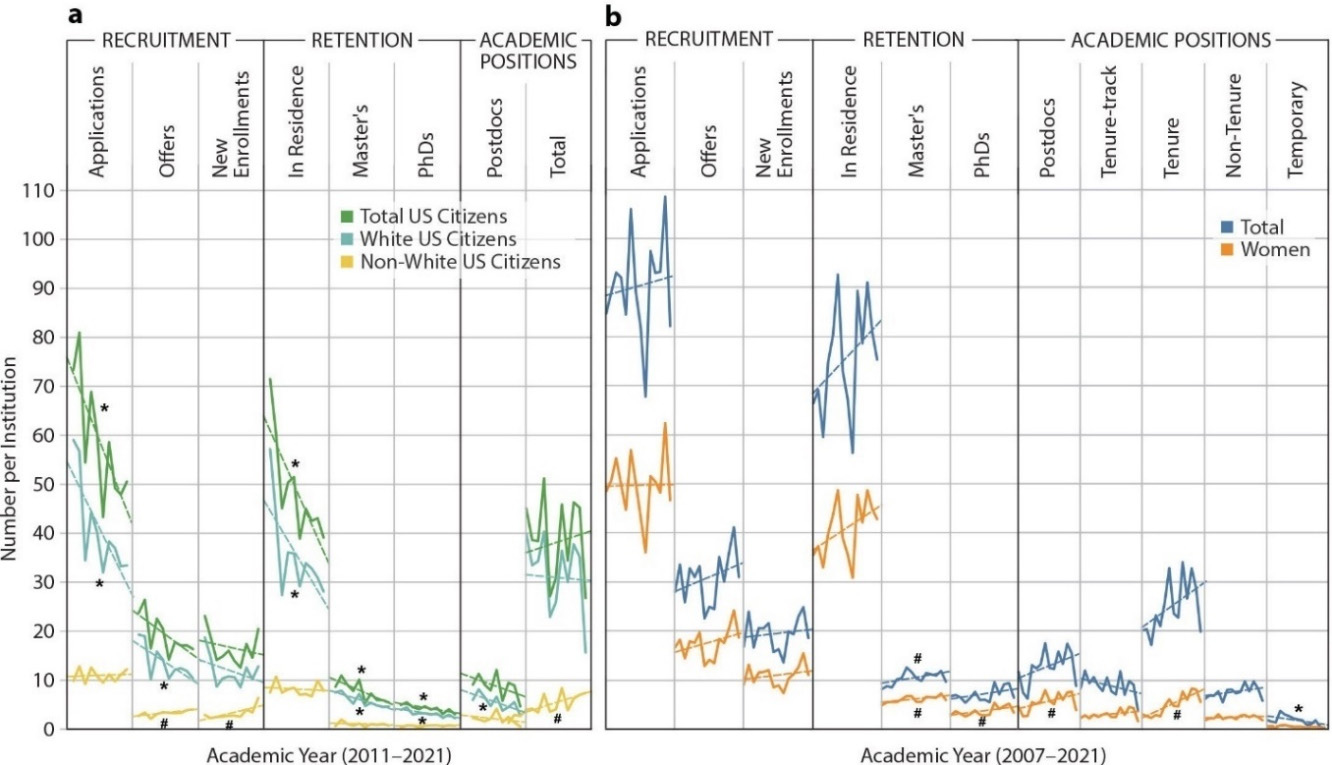

Current demographic trends in the ocean science workforce reflect a mixture of opportunities and challenges for increasing representation. For example, the percentage of non-White individuals in ocean sciences is low compared with the U.S. population. While new enrollment of non-White individuals in ocean science programs is increasing, that same trend is not seen in graduating students, indicating work is needed to retain these students (Figure 3.5a; Lewis et al., 2023; concerning contributing factors, see Graham et al., 2023). In addition, data suggest an overall decline in the number of U.S. citizens receiving degrees in ocean science disciplines (Lewis et al., 2023). As for trends in gender in the academic workforce (Figure 3.5b), data from 2007–2021 show ratios of women to men that are more or less equal in recruitment and retention of students; however, academic positions, particularly tenure-track and tenured, remain skewed toward employment of men.

Historically, among the Earth science disciplines, the ocean (and atmospheric) science workforce has notably low representation. The current lack of historically excluded representation may limit the breadth of perspectives available to tackle multifaceted ocean issues (Kappel et al., 2023). Previous National Academies reports (e.g., NASEM, 2023) have described the need to re-tool STEM education and build up a robust STEM workforce. Workers, including researchers, need both disciplinary and interdisciplinary knowledge and skills, and the ability and capacity to collaborate within transdisciplinary projects. This need increases the competition for obtaining skilled workers, significantly impacting hiring and retention issues. To ensure success in conducting basic ocean science research with transdisciplinary teams, the preparation and valuation of a skilled and innovative ocean science workforce is imperative.

Globally, most coastlines border low- and middle-income countries with less research and infrastructure capacity to address their nations’ ocean resource and marine hazard challenges. This may also be the case for some parts of the United States (i.e., the Gulf Coast), a topic examined in Chapter 4. Additionally, many biodiversity hotspots exist in relatively understudied geographies nearby underresourced populations (Stefanoudis et al., 2021). Such regions may fall victim to parachute science, wherein scientists from wealthier countries or regions conduct field research without meaningful engagement of and benefit to the local community or region (de Vos, 2020; de Vos and Schwartz, 2022). The United Nations (UN) has declared 2021–2030 the Decade of Ocean Sciences for Sustainable Development,6 recognizing the need for broader scientific engagement to create transformative ocean science solutions for sustainable development and societal needs. A shared framework called Leave No One Behind7 is one result of the UN decade provided to address barriers and biases in ocean science research.

The majority of coastal communities worldwide currently lack the resources and capacity to monitor and understand their own waters. In places where Indigenous knowledge exists, it is often devalued and disregarded, such that there are unequal and unbalanced collaborations. Since the global pandemic in 2020, a plethora of publications has suggested ways to broaden participation, promote welcoming spaces, and advance social impartiality in ocean sciences (e.g., Ali et al., 2021; Crosman et al., 2022; de Vos et al., 2023; Kaikkonen et al., 2024; Kappel et al., 2023).

___________________

6 See https://oceandecade.org.

7 See https://unsdg.un.org/2030-agenda/universal-values/leave-no-one-behind.

BOX 3.4

Workforce Development and the Blue Economy

The impact of climate change on coastal communities—including sea level rise, ocean acidification, food security, and human health—represents a major challenge to local, regional, and global economies and industries. With greater societal awareness of environmental issues, demand is growing for sustainable economic and environmental programs, plans, and budgets at the local, regional, national, and global levels. In turn, demand is also increasing for ocean engineering, cyberinfrastructure, data science, technology, and management programs that specifically address workforce development and leadership training needs to support this blue economy.

Leadership programs are offered at the graduate level, such as the Blue MBA at the University of Rhode Island (Moran, 2021; Moran et al., 2009) and the Ocean Enterprise Entrepreneurship Program at the University of Southern Mississippi, which combine business management with ocean science training for students to develop skills applicable to the new blue economy. Some undergraduate programs (e.g., University of New England’s B.S. in marine entrepreneurship) are also emerging. These programs align with recent programs and initiatives of the National Science Foundation’s Directorate for Technology, Innovation and Partnerships, including the Networked Blue Economy and Convergence Accelerator programs, which are designed to tackle challenges related to climate, sustainability, food, energy, pollution, and the economy.

Considering the broad spectrum of challenges of, and opportunities for, the growing blue economy, there will be an increased demand for such transdisciplinary technical skills and advanced academic programs in fields such as fisheries and aquaculture, ocean technology, engineering, ocean observing, renewable energy (Figure 3.4), marine biotechnology finance and risk management.

Transdisciplinary research and socioeconomic monitoring of blue economy initiatives will play an important role in developing policies for an ecologically and socially sustainable blue economy that minimizes common pitfalls of economic development. These pitfalls can include increased social disparity, “ocean grabs” with displacement of local residents, and degradation of local marine resources (see Germond Duret et al., 2023; Narchi et al., 2024). The development of new and innovative instructional programs provides an opportunity for greater collaboration between industry, government agencies, and academia in building a workforce pipeline that meets the needs of the blue economy.

SOURCE: Stephen Boutwell; Bureau of Ocean Energy Management.

SOURCE: Lewis et al., 2023.

Another important issue that the ocean science enterprise needs to tackle is improving work environments. Geoscience disciplines struggle with bullying, hostile work environments, discrimination, and sexual harassment aboard research vessels and in the field (Harris et al., 2022; Marin-Spiotta et al., 2020; NASEM, 2018; Women in Ocean Sciences Report, 2021). Because of lacking codes of conduct, reporting mechanisms, and fear of retribution, inappropriate behaviors often remain unchallenged (Seafarers International Research Centre, 2003). Environments that normalize, deal ineffectively with, or promote sexual or other forms of harassment negatively impact the physical and mental health of people who are experiencing it as well as those of bystanders. Toxic or unsafe working environments also deter people from entering or remaining in the field of ocean science.

CONCLUSION 3.2: Within the field of ocean science, it is imperative to ensure that people from all career stages, backgrounds, and ethnicities are protected from sexual harassment and bullying.

Cultivating the Future Ocean Science Workforce

Developing the next generation of ocean science experts, engineers, practitioners, managers, and decision-makers requires a multipronged approach to education, research, mentorship, advocacy, and engagement.

Building Basic Skills for Emerging Technologies

Building up basic skills within the future ocean science workforce is imperative to success. The field of ocean science generates vast amounts of data from satellites, underwater sensors, and at-sea research expeditions. Thus, supporting the advancement of expertise in integrating emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning into ocean science research not only helps analyze and interpret the data but also helps to improve the accuracy of oceanographic models and predictions. The skilled use of AI-powered systems could enhance ocean monitoring and surveillance efforts, for example,

by detecting illegal fishing activities, monitoring marine habitats, or identifying environmental threats such as pollution or coral bleaching, with a low amount of manual labor. This type of expertise can also be used in sophisticated analyses of large datasets, such as genomic data and bioinformatics, which can help scientists understand and manage the impacts of extreme weather and climate change on ecosystem processes and biodiversity. Training the ocean science workforce in using and applying new and emerging technologies is imperative to advance understanding of the ocean, address environmental issues quickly and efficiently, and promote sustainable management of marine resources. The global and national networks of coastal marine laboratories play an important role in training the next generation of undergraduate and graduate students, as further described in Box 3.5. Among the 99 labs that are members of the National Association of Marine Labs (NAML),8 80 percent are associated with one or more universities and most offer an array of courses and community programs at all ages and levels of education.

BOX 3.5

Marine Laboratories as Training Ground for Emerging Ocean Scientists

Marine laboratories are centers for training ocean science undergraduate and graduate students; they often have coastal access and/or fleets of small boats that can sample nearshore marine environments. Through initiatives and opportunities to enhance transdisciplinary research, marine labs need to co-develop questions to help address community-driven research needs. Parachute science has been common, especially in areas near marine labs, such as in the tropics, where there is a large discrepancy between the academic scientists and the local communities (e.g., Stefanoudis et al., 2021). Thus, as marine labs are typically in remote locations, where Indigenous and local knowledge of native species, ecosystems, atmospheric sciences, and oceanography may still exist, collaborations should be encouraged in engaging with local communities and training the next generation of ocean scientists.

Many labs engage in foundational fellowships and programs to enhance student populations, broadening perspectives in the marine sciences fields (e.g., the National Science Foundation [NSF] Advanced Technological Education program targeting Pacific Islanders at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa; Figure 3.6) and broadening geographic distribution, creating more balanced access points for entry into the field of ocean science than is currently offered by NSF-funded major ocean facilities (see Chapter 4). In 2023, the National Association of Marine Laboratories (NAML) reported that 435 internships were filled by underrepresented students across the member labs. NAML labs reported serving 199,592 K–12 students per year, as well as 9,572 undergraduates, 2,164 graduate students, and 2,707 teachers (NAML, 2023). They have also hosted summer camps and early childhood outreach and field trip programs for community engagement. U.S. marine labs are a significant influencer in educational experiences among the ocean science research infrastructure.

SOURCE: National Science Foundation (see http://nsf-ate.pbrc.hawaii.edu).

___________________

8 See https://naml.org.

CONCLUSION 3.3: Successfully addressing ocean science research challenges in the coming decade will depend on the cultivation and development of an expanded and transdisciplinary ocean science workforce. The workforce will benefit from receiving training in collaborative science methodologies, best practices for engaging in use-inspired research, and conducting research projects that meet societal needs.

Broadening Perspectives in the Ocean Science Workforce

Targeting recruitment for programs and fellowships from underserved communities, including Indigenous and local communities in the place of research (e.g., tribal colleges, organizations), redistributes investment within marginalized populations. Thoughtful and selective processes for the evaluation of qualified candidates for these opportunities will promote widening of perspectives and experiences within the field. Other strategies for broadening perspectives and place-based knowledge include providing training for teachers and principal investigators on collaborative science methods and multiple knowledge systems integration. Most important, a transdisciplinary lens requires working intentionally with the people of the place where research is being conducted, who have place-based knowledge of the ocean, coasts, and marine inhabitants, to seek unique solutions to pressing issues. It is also important to establish processes and guidelines to ensure a safe and welcoming culture in order to avoid tokenism and systemic bias. In addition, recruiting, training, and retaining international talent is crucial for the ocean science workforce and essential for maintaining U.S. research leadership. Incorporating international talent brings a multitude of perspectives, expertise, and innovation vital for addressing global marine challenges. Furthermore, researchers from less-resourced nations that are based at U.S. institutions are well-positioned to foster novel international collaborations that benefit both the United States and their home nations (when burdensome pitfalls are avoided; see Mwampamba et al., 2022).

Remote and autonomous sensors can provide global data coverage of the ocean, but rigorous, context-informed, and solutions-oriented science requires a global cadre of skilled researchers and collaborations. To ensure sustainable international collaborations, it is important to provide training for the U.S. workforce that fosters cultural competence, collaborative skills, ethical practices, and an understanding of differences in scientific approaches. Travel opportunities may also allow U.S.-based students and researchers to learn from established transdisciplinary ocean research programs in other countries. Partnerships for Enhanced Engagement in Research (PEER) was an international grants program established to support scientists in low- and middle-income countries that were partnered with U.S.-based collaborators on capacity-strengthening activities along the whole discovery-to-applied research spectrum. PEER was administered by the National Academies from 2011 to 2024 and managed by the U.S. Agency for International Development, with support from NSF and other federal agencies. Following the conclusion of funding for this program, NSF has the opportunity to support increased and more intentional collaborations between U.S.-based researchers and those in low- and middle-income global communities, enabling a fuller understanding of ocean sciences and supporting more international partnerships.

CONCLUSION 3.4: The field of ocean sciences represents an opportunity to engage the future and current workforce in an exciting area of expertise that will help develop STEM skills essential to a strong national workforce, regardless of whether the individual stays with the academic ocean sciences or ocean sciences more broadly. Every opportunity to go sea, work remotely with robotic systems, or work on samples taken from the water column or from seafloor cores can inspire and change the course of a career.

RECOMMENDATION 3.2: The National Science Foundation’s Division of Ocean Sciences (OCE) is uniquely positioned to shape the future of ocean sciences research and policy by cultivating a workforce that includes multiple skillsets and knowledge systems. OCE should:

- Explicitly support reskilling and upskilling, as well as mentorship, of the academic ocean science workforce to better engage with industry, entrepreneurs, interest holders, and other

- partners, to promote leadership development in seagoing technologies, data management, cultural competencies, and educational and mentoring practices.

- Support workforce development by investing in vocational and academic pathways, such as offering scholarships and apprenticeships; establishing fellowships with thoughtful considerations of metrics that support underserved student and professional populations, including students, researchers, or interest holders in the locations where the research is being conducted; and funding and incentivizing collaborative projects that bring together researchers from varied geographic and disciplinary backgrounds.

- Promote safe working environments by enforcing and incentivizing policies that protect people from discrimination, harassment, and bullying.

STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIPS

The committee acknowledges NSF’s efforts to cultivate partnerships between academia, industry, nonprofits, government, civil society, and other sectors to pursue transformative research, solve societal problems, drive economic progress, and build a future-ready workforce. NSF currently engages with other agencies and industry to achieve common goals and missions. It engages with industry to provide funding for companies to conduct scientific research and further develop the workforce they need. NSF also enters into cross-sector partnerships that help inform research and workforce directions, including with industry and other interagency partners. But NSF is not a mission agency, and its primary role is in funding basic research needed to develop tools that are then transitioned to mission agencies. For example, NSF funded the development of biogeochemical (BGC)-Argo floats through the National Ocean Partnership Program (NOPP) and subsequently has funded the deployment of 500 BGC-Argo floats in the global ocean through the Mid-Scale Infrastructure program.9 Recently, NOPP awarded $24.3M to advance research in marine carbon dioxide removal, with funding provided by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the Department of Energy (DOE), the Office of Naval Research, NSF, and the ClimateWorks Foundation. This funding opportunity is the “first large-scale public and multi-partner investment of research specifically focused on a suite of marine carbon dioxide removal approaches” (Ocean Acidification Program [OAP], 2023, para. 2).

In this regard, the committee commends OCE for its efforts to partner with agencies that bolster and leverage ocean science research more broadly, namely NOAA (ships), the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (satellites), and related mission agencies (U.S. Geological Survey, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management [BOEM], DOE, Office of Naval Research). This has been accomplished through interagency cooperative agreements and working groups. The committee encourages OCE to strengthen such interagency cooperation through existing federal policies and mechanisms to leverage NSF-funded basic ocean science research with those mission agencies. Additionally, the National Ocean Policy exists and could be modified as needed through additional executive order(s) to enhance the broader federal ocean research enterprise to meet national needs.

OCE also has a history of working with other NSF directorates as well as the Office of Integrative Activities to broaden opportunities for ocean researchers. For example, OCE has collaborated with the Directorate for Biological Sciences since the 2000s in funding several coastal Long-Term Ecological Research sites, such as the Santa Barbara Coastal, California Current Ecosystem, and Moorea Coral Reef, and more recently, oceanic sites such as the Northern Gulf of Alaska and North East U.S. Shelf.10 These sites will be critical for documenting physical, chemical, and biological change in the ocean over timescales necessary to understand ecosystem resilience and the impact of climate change on heat and carbon budgets in the ocean. The ocean research community has also been successful in working with the Office of Integrative Activities to obtain substantial new funding for establishing science and technology centers such as the Center for Coastal Margin and Prediction, Center for Microbial Oceanography, and Center for Dark Energy

___________________

9 See https://www.nsf.gov/awardsearch/showAward?AWD_ID=1946578 (accessed 12/23/2024).

10 See https://lternet.edu/network-organization/lter-a-history/ (accessed 12/23/2024).

Biosphere Investigations, in the past, and recently the Center for Chemical Currencies of a Microbial Planet.11 These centers have been successful at broadening participation and expanding available resources through partnerships with national labs, industries, and other entities. The Directorate for Technology, Innovation and Partnerships (TIP) program on Accelerating Research Translation also has potential for impactful partnership with OCE as it is focused on supporting higher education institutions that seek to build capacity and infrastructure for translation of fundamental academic research into tangible solutions that benefit the public.

These, and other strategic partnerships will no doubt be both necessary and critical to accomplishing the entire research portfolio laid out in Chapter 2. The committee acknowledges that, while the path to successful partnerships is the more difficult, the “path less traveled” (Figure 3.7) leads to several opportunities to work with entities outside of OCE to advance the ocean science of the next decade.

NOTES: Scientist and oceanographer Michael Freilich was director of the Earth Science Division in the Science Mission Directorate at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) headquarters from 2006 until 2019. One of Dr. Freilich’s greatest accomplishments at NASA was to forge long-term and enduring partnerships between NASA and multiple international space agencies. The road sign featured in this photo had very special meaning to him. He was a master at building strong partnerships, and the image encapsulates his deep understanding of the nature of the work required to take the turnoff to Partnership Road—the less-traveled road.

SOURCE: Michael Freilich.

___________________

11 See https://new.nsf.gov/od/oia/ia/stc#active-centers-c98 (accessed 12/23/2024).

Subject Areas Ripe for New Partnerships

Several opportunities for partnerships between OCE (i.e., chemical oceanography, biological oceanography, physical oceanography, and marine geology and geophysics programs, as well as major facilities, ships, and the Ocean Observatories Initiative) and other NSF directorates, as well as opportunities for public–private partnerships exist that would help progress the urgent ocean science research portfolio put forward in this report. Opportunities include addressing infrastructure needs such as the topics of big data, AI and machine learning, ocean model development and prediction tools, ocean observing platforms, and sensor development (and related technology/engineering), as well as emerging use-inspired research directions in ocean energy and aquaculture research and development (e.g., Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy Macroalgae Research Inspiring Novel Energy Resources), seabed mining for critical minerals, marine carbon dioxide removal, and subseafloor carbon capture. These inter- and transdisciplinary areas overlap with other federal agencies and organizations and represent an opportunity to leverage federal investment with the private sector. A few of these examples are highlighted in further detail below.

Ocean Observing

Several autonomous surface vessel companies have greatly expanded the capacity and capability to observe the ocean, with a suite of uncrewed platforms developed to collect ocean (e.g., temperature salinity, dissolved oxygen) and seafloor bathymetry data, among other ocean observing capabilities. These companies (e.g., Saildrone, SeaTrac, Liquid Robotics, OceanAero, Subsea Sail) may represent an opportunity for OCE-funded scientists and engineers to work with industry to utilize the technology or the data being collected. Additionally, the Naval Oceanographic Office maintains a fleet of gliders and other remote vehicles that could be made into a shared resource through a partnership with the Office of Naval Research (ONR). Traditionally, NSF and ONR have worked together to provide access to research vessels (see Chapter 4), but this partnership could be strengthened through joint projects, technical exchanges, and appropriate data sharing.

Fiber optic cables also present the opportunity to make high-precision measurements that can be used for seismic sensing. Specifically, distributed acoustic sensing is a relatively new technology that allows real-time measurements along the full length of a fiber optic cable. Additionally, telecommunication cables can be instrumented through the SMART (Science Monitoring and Reliable Telecommunications) cables initiative. Partnerships with telecommunication companies have the potential to vastly increase the area of the seafloor that can be monitored seismically, improving earthquake warning systems and seismic imaging of Earth’s interior. For a relatively low cost, existing fiber optic cables can be instrumented for distributed acoustic sensing. Moreover, while traditional approaches previously necessitated using “dark” (or unused) fibers, new technologies are being developed to use “lit” (or active) fibers as ocean observation platforms, greatly expanding the potential use of distributed acoustic sensing across the seafloor.

In addition, considering its preeminent role in developing and deploying advanced cyberinfrastructure, NSF’s Directorate for Computer and Information Science and Engineering is an important partner for OCE in terms of cabled observatories and the Academic Research Fleet.

Biotechnology

The explosive growth of DNA sequencing, analysis, and manipulation, along with the keen interest in use of novel genes and gene pathways in creating new industrial-scale bioproducts, opens up the biotechnology and bioinformatics sector as a partner for future ocean exploration. For example, marine micro-algae have been proposed as a crucial source of nutrients and food (Greene et al., 2022) for humans and for food production in aquaculture settings. Additionally, antifreeze genes from polar ice fish, which allow adaptation to subzero ocean temperatures, have been used across a wide range of industries (Eskandari et al., 2024). Furthermore, bioinformatics tools are widely used in collecting samples from ocean sediment

and water microbial exploration. The speed of the advancement of genomic research, coupled with the rise of autonomous vehicles to collect samples, has led to the development of new autonomous DNA samplers.

Another area for partnership and technology transfer is the biomedical field. For example, Prochlorococcus, the most numerous photosynthetic organism on earth, was not discovered until flow cytometer technology, originally developed for medical applications, was used by oceanographers to analyze ocean water samples (Chisholm et al., 1988). DNA sequencing technology developed for the Human Genome Project fundamentally changed marine microbial oceanography by introducing shotgun metagenomic sequencing methods for ocean research (Rusch et al., 2007). And the reverse flow of ideas and methods has also occurred, with researchers trained in marine microbial ecology contributing to human microbiome science (Dubilier et al., 2015). The biomedical field, specifically partnership with the National Institutes of Health, offers additional opportunities for OCE to play a strategic role in enabling new resources and transfer of knowledge to the oceanographic community.

In all of these cases, basic discoveries in ocean sciences (e.g., heat-tolerant enzymes, new types of symbioses) are coupled with an industrial capacity to create products of value to society. Fostering these connections emphasizes the important role that ocean biotechnology plays in discovery and provides a way to augment the physical and chemical ocean sensing work done by other sectors within the field of ocean sciences.

Ocean Renewable Energy and Workforce Development

Developing new technologies and training a workforce on ocean-based renewable energy presents a ready opportunity for cross-directorate collaboration, for example through the NSF Clean Energy Initiative. Development of new instrumentation, maintenance of and improvement to equipment related to ocean-based systems, and data management efforts to ensure the quality and accuracy of the data and the analysis of large datasets generated by these systems all require a workforce with specialized training in ocean sciences, engineering, manufacturing, and data science.

Aquaculture and Mariculture

Several examples of NSF-funded projects to advance research and workforce development relate to aquaculture. The NSF Convergence Accelerator program has supported research on commercial marine fish production by developing sustainable feeds, establishing feed suppliers, and enhancing market acceptance. Another example relates to public policy, where NSF has supported research to examine the effectiveness of marine aquaculture partnerships measured by the emergence of new social capital, learning and consensus on scientific and policy issues, formal policy agreements, policy adoption by higher authorities, and projected socioeconomic and ecological outcomes. Third is the NSF TIP Directorate–funded research project BioSPACE: Biosensing Surveillance of Pathogens in Aquaculture and Coastal Environments. This project is focused on the development of a data analytics platform that uses biosensors to detect harmful organisms, such as Vibrio and Pseudomonas, in aquaculture farms and coastal waters. Aquaculture is driven by public demand for seafood protein, products and materials, and is therefore inherently opportune for partnering with the seafood and related industries. This field is also an important opportunity to engage subsistence fishing communities, or those with local and Indigenous knowledge on the species and their response to ecosystem changes.

The U.S. Merchant Marine

It has long been recognized that the ships of the U.S. Merchant Marine and other such organizations could be equipped with instrumentation requiring minimal human intervention to acquire routine oceanographic data in key locations (Rossby et al., 1995). For example, the M.V. Oleander has been operating between New Jersey and Bermuda for several decades, collecting oceanographic data. With NSF and other

federal agency funding, the Oleander was equipped with an acoustic doppler current profiler and the capability to deploy expendable bathythermograph sensors. The result has been a valuable multiple-year time series of temperature and vertically resolved currents measurements across the Gulf Stream (Rossby et al., 2017)—one of the most important currents in the ocean. Additional partnerships with the Merchant Marine are an opportunity to build even more time series of important oceanographic variables, such as vertically resolved currents, temperature, salinity, and light detecting and ranging (LIDAR)-determined ocean particulate material. The data are most valuable when the route of an instrumented merchant ship is known far in advance, and the ship makes repeated crossings on the same route.

Additional Opportunities and Resources for Partnering with Industry

There is a pronounced need for targeted programs to strengthen the capacity of the academic ocean science workforce, in order to connect more productively with industry and local partners, and to engage effectively with innovation and entrepreneurship activities. Such programs can take the form of professional development activities or of incentive programs. These programs could be geared towards enabling the academic workforce to reimagine applications of its work in the context of innovation and entrepreneurship. Academic faculty are well-trained in conceiving projects that are driven by hypotheses and research questions; however, translation of their work into technological advances and/or commercializable products requires unique skills and partnerships, which can be encouraged through targeted funding calls, such as the Accelerate Research Translation program, aimed at the ocean science community.

CONCLUSION 3.5: Partnerships inherently include multiple sectors and are an important component to the transdisciplinary research approach to ocean and Earth science. Developing strategic partnerships will be both necessary and critical to accomplishing the ambitious and urgent research portfolio put forward in this report, specifically in observing the ocean (including platforms, data, and technology development) across ocean physics, chemistry, biology, and geology.

- The NOPP is an example of an existing program that fosters interagency and industry support for basic curiosity- and discovery-driven ocean science research. Partnerships such as NOPP, while sometimes challenging to implement, can lead to highly impactful programs being established.

- Creative ways of thinking about new partnerships can result in cost-effective ways to access the ocean. For example, partnerships with groups such as the U.S. Merchant Marine and the U.S. Coast Guard have the potential to allow scientists to acquire and sustain key ocean measurements in critical parts of the ocean without utilizing ship time in the U.S. Academic Research Fleet.

- Opportunities exist to partner with related mission agencies (e.g., NOAA, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, National Institutes of Health, ONR, and BOEM), as well as with other NSF directorates (e.g., TIP, Computer and Information Science and Engineering, and Biological Sciences).

RECOMMENDATION 3.3: To bolster and leverage urgent ocean science research over the next decade, National Science Foundation’s (NSF’s) Division of Ocean Sciences (OCE) should explore various ways of bringing new resources to this work, including expanding partnership with other NSF directorates, related mission agencies, and other organizations. OCE should seek greater interagency cooperation through federal policies and mechanisms for leveraging NSF-funded basic ocean science research with those mission agencies. Developing new partnerships in ocean sciences, as well as other disciplines, may increase support available for the development of new technologies, data curation, solutions-oriented research, and the basic research that will fuel these developments.