Forecasting the Ocean: The 2025–2035 Decade of Ocean Science (2025)

Chapter: 4 Facilities and Infrastructure for the Next Decade

4

Facilities and Infrastructure for the Next Decade

This chapter assesses the infrastructure needed to achieve the ocean science research of the next decade. The evaluation of needs is parsed into four categories: major infrastructure (Academic Research Fleet [ARF], Ocean Observatories Initiative [OOI], and scientific ocean drilling), additional supporting infrastructure, underutilized or emerging infrastructure, and cyberinfrastructure. As long-term major investments in ocean science infrastructure supported by the National Science Foundation’s (NSF’s) Division of Ocean Sciences (OCE), the discussions of major infrastructure include a high-level program assessment as well as the role of that infrastructure in supporting the urgent ocean science research portfolio.

The conclusions and recommendations in this chapter focus specifically on supporting the three urgent ocean science questions outlined in Chapter 2:

- Ocean and Climate: How will the ocean’s ability to absorb heat and carbon change?

- Ecosystem Resilience: How will marine ecosystems respond to changes in the Earth system?

- Extreme Events: How can the ability to forecast extreme events driven by ocean and seafloor processes be improved?

The conclusions and recommendations are not intended to reflect all the possible ways OCE-sponsored research will use OCE facilities and infrastructure. Furthermore, a full suite of conclusions related to scientific ocean drilling can be found in the committee’s interim report (NASEM, 2024b), and it is important that the present report be read in the context of that interim report.

Table 4.1 provides an overview of the infrastructure needed to accomplish these three urgent ocean science research questions for the next decade, as justified in the text that follows.

MAJOR FACILITIES

OCE-sponsored research relies heavily on facilities and infrastructure funded by OCE and other agencies, with the most expensive NSF-funded programs being the U.S. Academic Research Fleet, the Ocean Observatories Initiative, and the Ocean Drilling Program. The annual cost of operating these three facilities accounts for about 50 percent of the OCE budget; the operating cost of the ARF is the most expensive (Figure 4.1). Note that for OOI and NSF-owned vessels, the costs shown in Figure 4.1 do not include construction, which were covered by a separate NSF funding account (Major Research Equipment and Facilities Construction) nor development costs that were covered by the OCE core budget prior to construction completion. Costs associated with operating the vessels in the ARF have risen significantly in recent years driven by fuel costs, salary increases required to keep experienced and competent vessel crews, and addressing technology needs associated with modernizing the fleet. As discussed below, modern ocean facilities are crucial for the research related to addressing the urgent research questions presented in Chapter 2.

Scientific ocean drilling was covered in detail in the 2025 Decadal Survey interim report (NASEM, 2024b). Expanding from that foundation, this final report evaluates scientific ocean drilling in the broader context of ocean sciences. The discussion provides background information and an assessment of infrastructure needs only in relation to the three science questions proposed in Chapter 2. The committee recognizes that science priorities beyond the three research questions may have different infrastructure needs.

Academic Research Fleet

Oceanographic research vessels are the fundamental platform for the field of ocean sciences to conduct research in the past, present, and for the foreseeable future. NSF-supported scientists and researchers

funded by other agencies and the private sector have been using the ARF for decades, demonstrating how the fleet has contributed to research and how the fleet will support research in future.

NSF and other federal agencies oversee the ARF through awards to each ship-operating institution and via the 53-year partnership with the University-National Oceanographic Laboratory System (UNOLS). UNOLS matches vessel use requests with available assets for oceanographic research by implementing a scheduling framework and by providing a forum for collecting recommendations and community priorities for replacing, modifying, or improving facilities. At the time of this report, UNOLS and NSF coordinate the scheduling of scientific expeditions aboard 17 vessels 1located at 14 operating institutions.

The ARF consists of a fleet of oceanographic vessels (Table 4.2), three submersibles, and an autonomous vehicle, which are owned and operated by a combination of NSF, the Office of Naval Research (ONR), universities, and private entities. Vessel operations are supported through a contract with the agency that owns the vessel. The responsibilities of the contractor, generally an academic institution, includes crewing the vessel, providing a home port, and arranging the shipping of scientific gear and supplies to and from the vessel. All vessels in the ARF must be operated in accordance with UNOLS safety standards, undergo inspections, address performance standards, fulfill reporting requirements, and be accessible to the scientific community for the purpose of supporting national interests in marine science and engineering research and education and for fulfilling agency missions. Recently, cybersecurity has also been recognized as increasingly important and has become a requirement for ship operators. OCE recently created a new program officer position dedicated to improving cybersecurity for the ARF.

TABLE 4.1 Infrastructure Needs to Address Urgent Priorities for Ocean Sciences Research, 2025–2035

| Ocean and Climate | Ecosystem Resilience | Extreme Events | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Major Facilities | |||

|

Academic Research Fleet (ARF)a |

R | R | R |

|

Scientific ocean drilling capability |

R | G | Rb |

| Ocean Observatories Initiative Arrays | |||

|

Pioneer |

R | I | Gc |

|

Cabled |

I | NDE | Rb,c,d |

|

Endurance |

Rd | I | Gc |

|

Open Ocean |

Rd | I | Gc |

| Infrastructure Assets | |||

|

Non-UNOLS, non-ARF institution-owned research vessels |

Rd | R | R |

|

Marine laboratories and stations |

Rd | R | R |

|

Autonomous platforms |

R | R and NDE | Rc and NDE |

|

Geophysical Instrumentation |

NR | NR | Rb |

|

Instrumented cables |

Rd | G | Gb |

|

Ocean biotechnology |

NDE | NDE | NDE |

|

Novel sensors |

R and NDE | R and NDE | R and NDE |

|

Cyberinfrastructure |

R and NDE | R and NDE | R and NDE |

a Including the National Deep Submergence Facility

b For geological extreme events (e.g., earthquakes)

c For water column extreme events (e.g., severe storms, changes to Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation)

d For heat absorption

NOTES: G = good, if a byproduct of a primary driver; I = important but not required; NR = not required; NDE = needs development or more evaluation in relation to the needs of the urgent science questions; R = required; UNOLS = University-National Oceanographic Laboratory System.

___________________

1 This sentence was changed after release of the report to correct the number of vessels in operation.

SOURCE: NSF, n.d.-b.

The primary agencies funding the at-sea operations of the ARF are (in order): NSF, the Navy (ONR), and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). From 2013 to 2023, agency-funded research on ARF vessels averaged a total of 3,000–3,500 annual days at sea, with each agency funding ship operating costs for the days their respective funded research programs used the vessels. Other operational funding comes from other federal, nonfederal, private, state, and other sources, including the operating institutions that annually purchase days at sea for educational and other uses.

TABLE 4-22 Status of Ships in the Academic Research Fleet

| Ship Class Ship Name |

Year Built | Owner | Length overall m(ft) | Science Berths | Total Ship Days Used (2022) | End Year | Scientist-Days at Sea (est.)a | Host Institution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global | ||||||||

| Thomas G. Thompson | 1991 | Navy | 84 (274) | 36 | 268 | 2036 | 9,648 | University of Washington (UW) |

| Roger Revelle | 1996 | Navy | 84 (274) | 37 | 299 | 2041 | 11,063 | Scripps Institution of Oceanography (SIO) |

| Atlantis | 1997 | Navy | 84 (274) | 37 | 244 | 2042 | 9,028 | Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution |

| Marcus G. Langseth | 1991 | LDEO | 71 (235) | 35 | 216 | 2028 | 7,560 | Columbia University |

| Sikuliaq | 2014 | NSF | 80 (261) | 26 | 264 | 2045b | 6,864 | University of Alaska Fairbanks |

| Ocean/Intermediate | ||||||||

| Kilo Moana | 2002 | Navy | 57 (186) | 29 | 259 | 2032b | 7,517 | University of Hawaiʻi |

| Endeavor | 1976 | NSF | 56(185) | 18 | 162 | 2026 | 2,916 | University of Rhode Island |

| Atlantic Explorer | 1982 | BIOS | 51 (168) | 20 | 212 | 2026 | 4,240 | Bermuda Institute of Ocean Sciences (BIOS) |

| Neil Armstrong | 2015 | Navy | 73 (238) | 24 | 276 | 2045b | 5,424 | Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution |

| Sally Ride | 2015 | Navy | 73 (238) | 25 | 173 | 2046b | 4,325 | SIO |

| Regional | ||||||||

| Hugh R. Sharp | 2005 | UDEL | 44 (146) | 14 | 163 | 2035b | 2,282 | University of Delaware (UDEL) |

| Taanic | 2027 | NSF | 60 (199) | 14 | NA | 2053b | NA | Oregon State University |

| Narragansett Dawnc | 2027 | NSF | 60 (199) | 14 | NA | 2054b | NA | University of Rhode Island |

| Gilbert R. Masonc | 2028 | NSF | 60 (199) | 14 | NA | 2054b | NA | The University of Southern Mississippi |

| Coastal/ Local | ||||||||

| Robert Gordon Sproul | 1981 | SIO | 38 (125) | 12 | 131 | 2030 | 1,572 | SIO |

| Pelican | 1985 | LUMCON | 36 (116) | 14 | 220 | 2027 | 3,080 | Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium (LUMCON) |

| Walton Smith | 2000 | Univ of Miami | 30 (96) | 16 | 50 | 2030 | 800 | University of Miami |

| Savannah | 2001 | SkIO/UGA | 28 (92) | 19 | 135 | 2039 | 2,565 | Skidaway Institute of Oceanography (SkIO)/University of Georgia (UGA) |

| Blue Heron | 1985 | UMINN | 26 (86) | 6 | 110 | 2030 | 660 | Large Lakes Observatory |

| Rachel Carson | 2003 | UW | 22 (72) | 9 | 123 | 2033 | 1,107 | Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute |

a Estimated by multiplying “Science Berths” by “Total Ship Days Used”

b Lifetime expected to be extended by a mid-life refit.

c Regional Class Research Vessels are expected to be operational no earlier than 2027.

NOTES: NSF = National Science Foundation; LDEO = Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory; UMINN = University of Minnesota.

SOURCE: https://UNOLS.org.

___________________

2 This table was changed after release of the report to correct End Year data.

Current State of the Academic Research Fleet

From 2024 to 2030, the end of life is scheduled for three intermediate-class vessels (Endeavor, Atlantic Explorer, and Kilo Moana); four coastal-/local-class vessels (Robert Gordon Sproul, Pelican, Walton Smith, and Blue Heron); and a global-class vessel (Marcus G. Langseth). As an estimate of what capacity will be lost and what will be replaced with new vessels, the information in Table 4.1 (multiplying columns 5 and 6 and summing for the ships named above) suggests a potential loss of more than 32,000 scientist-days at sea per year. It is only an estimate, because this calculation assumes that the days at sea in column 5 of Table 4.1 are representative of future usage and that the ships sail with a full complement of scientists. The estimated losses will be partly mitigated when the new NSF-owned regional-class research vessels (RCR/Vs) Taani, Narraganset Dawn, and Gilbert R Mason (Figure 4.2) become operational, estimated to be no earlier than 2027. Assuming the new vessels will spend about 200 days at sea, they will provide about 8,500 scientist-days at sea. The committee notes some unique exceptions, that may, in fact, improve the gap in scientist-days at sea in the future. For example, with the R/V Sproul, scheduled to retire in 2025, Scripps Institution of Oceanography will be obtaining a new ship with funding by the state of California. The ship design has been completed, and construction will begin soon. Nonetheless, there remains a deficit from the upcoming retirements as described here.3

A loss of geographic distribution is also noted. In the Atlantic Ocean, Endeavor, Atlantic Explorer, Smith, and Savannah represent approximately 10,000 scientist-days at sea. Narragansett Dawn, when launched, will provide approximately 2,800 scientist-days at sea. Blue Heron, the only vessel in the Great Lakes, faces retirement without a replacement, which would leave no ARF vessel operating in the Great Lakes. In the Pacific Ocean, Taani will provide potentially 2,800 scientist-days at sea, while the retirement of Sproul and Kilo Moana will equate to a loss of more than 10,000 scientist-days at sea. The committee does not know of a replacement for the Kilo Moana. Following retirement of Pelican and Walton Smith, only one ARF ship, the new RCR/V Gilbert R. Mason, will operate in Gulf waters, supporting approximately 2,800 scientist-days at sea per year.

NOTES: Oregon State University is the prime contractor and will operate the first in the class (R/V Taani). The University of Rhode Island and a consortium led by University of Southern Mississippi/Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium will operate the second and third vessels in the class.

SOURCE: Oregon State University and Glosten Associates.

___________________

3 The paragraph was updated after release of the report to correct some details about the new ship.

These losses impact the ability to conduct responsive research in the wake of coastal maritime disasters. It should also be noted that by the end of the decade, all local- and coastal-class ARF vessels will exit the fleet. Planning for new vessels is a long and costly process; based on recent ARF experience with the NSF-owned RCR/Vs, as well as the Navy-owned Sally Ride and Neil Armstrong, more than a full decade is required from “conception to implementation.” Thus, these retirements pose an existential risk to achievement of the scientific goals outlined in this report.

CONCLUSION 4.1: In the coming decade, research vessel capacity will be reduced, owing to the end-of-life of multiple research vessels. The new NSF-built RCR/Vs will replace only some of the loss of scientist-days at sea from retired vessels, and their capabilities differ from many of the ships scheduled to be retired. Replacement plans of the Navy-owned Kilo Moana and various vessels owned by different state governments are not known, raising the possibility that ocean science research could be significantly hindered by a substantial decrease in the capabilities and assets available to scientists to conduct oceanographic research.

Geographic Distribution in Vessel Operations

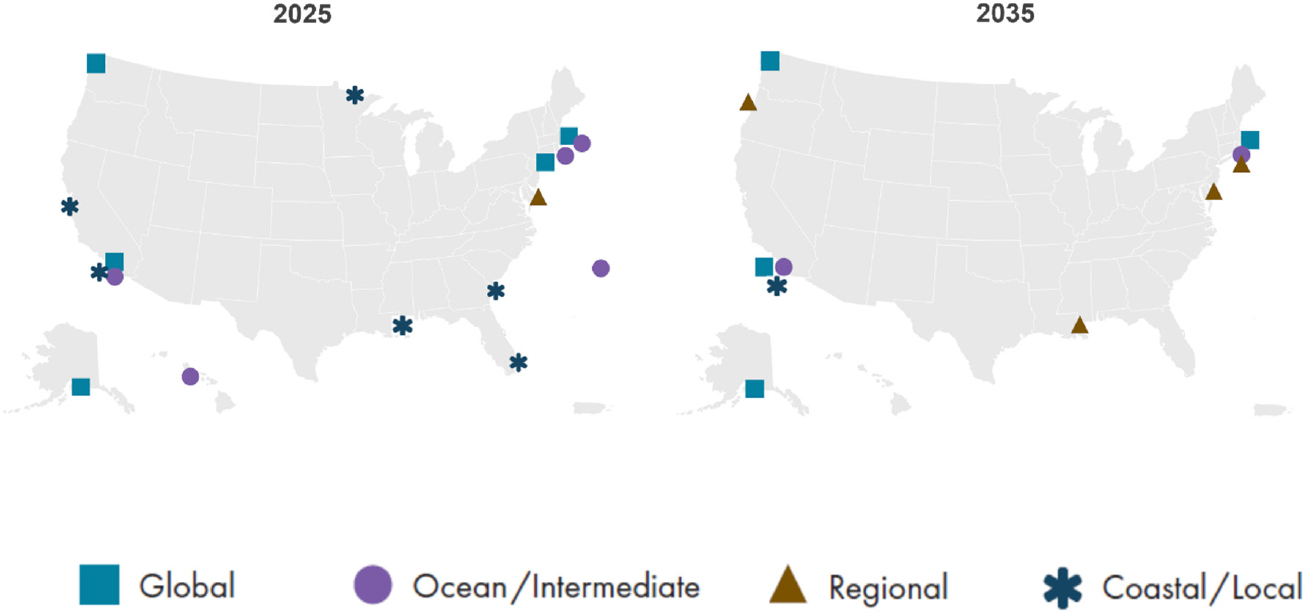

A vessel’s home port is often a hidden driver on where and by whom scientific research occurs; it also determines who is exposed to shipboard experiences, starting as early as K–12 students. Broader impact efforts conducted as part of NSF-funded research programs and ship operation grants often speak to the ability to engage students and the public through experiential activities connected with the ships. The committee examined the geographic distribution of ship operations across the ARF to determine whether all scientists throughout the United States could participate in addressing the three research themes discussed in this report by utilizing a research vessel from the ARF in their home waters. Currently, most global- and ocean-class vessels are operated by institutions along the U.S. Atlantic and Pacific coasts (Figure 4.3), an appropriate distribution if they are only supporting the research along the respective coasts and farther offshore, as evidenced by ship utilization days (Table 4.2). This bicoastal utilization is set to continue based on current vessel replacement plans.

NOTES: Four global-class and two ocean-class vessels are owned by the U.S. Navy (Kilo Moana, Atlantis, Thompson, Revelle, Armstrong, and Ride). The end-of-life for Atlantis, Thompson, and Revelle, which underwent a midlife refit, will occur between 2036 and 2042. In addition, the two Navy-owned ocean-class ships are due for a midlife refit in 2041 and 2042.

SOURCE: UNOLS Office.

However, ship-based research along the Gulf Coast, consisting of 1,680 miles (2,700 km) of coastline, is currently supported by only one coastal-/local-class ARF vessel and otherwise supported by a mosaic of aging coastal- and local-class vessels operated by academic institutions in the region. The largest and most capable non-UNOLS vessel operating is R/V Point Sur, a first-generation RCR/V retired from the ARF in 2015 and subsequently operated in the Gulf at The University of Southern Mississippi for the entirety of the last decade. This ship is scheduled for retirement upon the arrival of R/V Gilbert R. Mason. As evidence of the robust appetite for research in the Gulf, R/V Point Sur’s ship-based research days of operation in 2022 were 180, with 25 days supporting NSF-funded research. R/V Pelican and R/V Point Sur together have averaged over 400 days of operation (2020 and 2021 are exceptions, due to COVID) since 2015, including nearly 6,000 scientist-days at sea annually, displaying interest in oceanographic research in the U.S. Gulf Coast region.

NSF awarded a new RCR/V, the R/V Gilbert R. Mason (Figure 4.2) in 2019 to the region to be operated by the Gulf-Caribbean Oceanographic Consortium led by The University of Southern Mississippi and Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium (LUMCON). As the third build in this new class of ships, current project timelines place delivery and start of operations no earlier than the end of the current decade. The new RCR/V will provide an oceanographic ship capable of supporting research throughout the Gulf and surrounding open waters. R/V Gilbert R. Mason will then be the sole UNOLS vessel dedicated to supporting coastal and near-shore work in the U.S. Gulf Coast region, home to more than 200 million people.

By the end of the next decade, all ARF vessels located in the southeast United States other than the new Gilbert R. Mason, will have reached end-of-life. In addition, all other coastal-/local-class vessels will have retired, including the vessel now operating in the Great Lakes. As pointed out above, location can determine what science occurs, where, by whom, and the communities that are engaged. This lack of available seagoing ocean science infrastructure may create scientific research and workforce inequities in the southeast United States, the Great Lakes region, and potentially the Pacific Islands due to a lack of NSF-supported opportunity in their respective backyards.

Another aspect of the geographic distribution in vessel operations is consideration of vessel capabilities in polar waters and adjacent seas. The NSF-owned and ice-capable global-class R/V Sikuliaq is an effective platform for studying ice-covered polar waters in both the northern and southern hemispheres. There is, however, a need for additional icebreaking capability to augment/replace the current aging U.S. icebreakers, particularly in the Antarctic region, as concluded by a recent NASEM report, Future Directions for Southern Ocean and Antarctic Nearshore and Coastal Research (NASEM, 2024d). The added capacity for enabling polar research, as described in Future Directions would support research in polar waters and help meet the challenge for the next decade and associated ocean science research priorities described in this report.

Oceanographic ships do not operate in isolation. Around vessel operations, other facilities (equipment and services) are needed to meet the needs of supporting shipboard science, thereby supporting a strong workforce and ocean economy in home port locations. Further, NSF currently supports 14 equipment and service pools or groups which, with few exceptions, also follow a bicoastal model, resulting in shipping costs and time delays for research in areas where these assets are lacking locally. NSF has highlighted geographic concentration of funding and resources in other directorates, with the goal of ensuring that research and innovation are not confined to geographical boundaries but are easily available across the nation (NSF, 2024a, 2024b). How geographical concentration of ocean science infrastructure impacts the pace and scope of ocean and coastal research may also be worth considering.

CONCLUSION 4.2: The committee recognizes the importance of access to infrastructure in order to support priority ocean science research. In addition to meeting the immediate needs of ocean research and education, over the long-term, the local and regional communities that host ocean research infrastructure benefit intellectually, economically, and socially from these national investments. For example, regions that support significant infrastructure are more likely to engage the citizenry with K–12 education, paired curriculum with nearby institutions of higher education, and develop a work-

force with high technical capabilities. Therefore, such investments offer an opportunity beyond science to strengthen multiple critical sectors that are of national interest and develop an ocean-literate citizenry that is well poised to engage in societal solutions.

Global-Class Research Vessels

Global-class research vessels are more heavily used than the other classes of vessels in the ARF (Table 4.2), meeting the critical need of research programs that require a large, interdisciplinary scientific party and/or a large platform for launching heavy equipment to study ocean processes in the global ocean. Global-class vessels can operate for longer periods at sea than the smaller classes of vessels and in more challenging sea state conditions. They also can carry a heavier load of deployable oceanographic instruments (e.g., current meter arrays) than other vessels, and Atlantis provides support for the NSF-supported deep submergence vehicles (Alvin and Jason). Multiplying the number of scientific berths by ship days at sea shows that the global-class ships support approximately 50 percent of the scientists at sea that use vessels scheduled by UNOLS (Table 4.2). The end-of-life of the three Navy-owned global-class ships (Thompson, Atlantis, and Revelle) occurs in the relatively short period of 2036–2042. Furthermore, the midlife refits of the Navy-owned ocean-class ships (Armstrong and Ride) occur only a few years later. Replacing these three global-class ships and refitting these two ocean-class ships is of critical importance to regaining U.S. leadership in the ocean sciences. Replacing the three global-class ships and refitting the two ocean-class ships within about a 6-year period will be a significant expense for the Navy. Now is the time to plan for this challenge, since a new oceanographic ship takes more than a decade from the start of serious planning until start of construction.

The global-class research vessel Marcus G. Langseth, owned and operated by Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory (LDEO) with support from NSF, is the only ARF vessel capable of collecting the full range of active-source seismic data needed by the academic community. It also serves as the National Facility for Seismic Imaging. Currently, the Marcus G. Langseth is operational through 2024, with no announced long-term plan to replace it, although the committee was informed that discussions between LDEO and OCE are underway.

The need for global-class ships, while critical, is not new, and the fact that it persists speaks to the fundamental importance of seagoing research activities to fulfill national scientific objectives. Indeed, the National Research Council (2009) report Science at Sea: Meeting Future Oceanographic Goals with a Robust Academic Research Fleet stated, “The future academic research fleet requires investment in larger, more capable general purpose Global and Regional class ships to support multidisciplinary, multi-investigator research and advances in ocean technology” (p. 83). While NSF has fulfilled part of this with the new RCR/Vs coming online shortly, the portion of this recommendation regarding global-class vessels has only grown in importance and is now acute.

CONCLUSION 4.3: Three Navy-owned global-class ships (R/Vs Thompson, Revelle, and Atlantis) and the Langseth face end-of-life in the near future. Midlife retrofits are scheduled for two Navy-owned ocean-class ships (R/Vs Armstrong and Ride). Refitting the ocean-class ships and replacing the four global-class vessels with those that have comparable or enhanced capabilities is necessary to accomplish high-priority ocean research over the coming decades and to regain U.S. leadership in providing researchers access to the ocean. The U.S. government needs to develop substantive planning and budget strategies now, as private and philanthropic seagoing opportunities are not considered true replacements for these vessels.

Science Party Users

The range of operations and disciplinary breadth of users is a strength of the ARF, which hosts many different types of investigators on board, including atmospheric scientists, engineers, and informal science educators, which expands the pool of users among the science community. The science parties working on

board ARF vessels typically include scientific faculty, staff, and students from various universities and research institutions, as well as skilled technicians to operate the sophisticated sampling devices and electronic systems required to collect data. Additionally, as Table 4.3 shows, students and educators (primarily K–12) are typically well represented in the makeup of the science party. Graduate students and postdocs are essential full-standing members of most science parties and are often deeply involved in research programs, doing much of the hands-on work at sea. NSF has made additional investments in providing support for early career training onboard vessels during select expeditions. These focused experiences help prepare early career scientists to write seagoing proposals and to be first-time chief scientists.

The U.S. scientific and ocean education community’s access to time at sea via research vessels is invaluable to building a skilled ocean science workforce. Studies have shown that experiential learning (i.e., learning through hands-on experience) can lead to unique insights that are harder to achieve without firsthand experience. For example, a recent large-scale study by Lin and colleagues (2023) showed that remote collaboration fuses fewer breakthrough ideas than in-person, face-to-face collaboration. Lin and colleagues (2023) found that researchers working in the same space better integrate early career scholars into conceptual tasks, which can serve as a launching point for advancing scientific careers. In the ocean sciences, at-sea research programs create such spaces and thus need to be available broadly across geographies.

CONCLUSION 4.4: NSF has played an important role in ocean science workforce development by providing support for early career training onboard vessels. These focused experiences help prepare the next generation of ocean scientists and ocean science leaders. U.S. scientific access and the ocean education community’s access to time at sea via research vessels is critical for building the future ocean science workforce.

Moreover, with the many advances in robotics and artificial intelligence, it is tempting to believe that lower-cost autonomous vehicles could do the work of a staffed research vessel. This is simply not the case for a number of well-established reasons. First, seagoing scientists are constantly adapting to unforeseen conditions and situations, and being at sea ensures that the data collected are most appropriate to meet their scientific goals. Second, many of the most profound discoveries in the field of ocean sciences have been made by scientists at sea. The committee posits that bringing the advances in autonomy, robotics, and computer science onto the research vessel will yield even more robust and thorough observations while still leading to ground-breaking and unexpected revelations. Third, currently and for the foreseeable long-term future, the physical capabilities of autonomous vehicles cannot fulfill the scientific mission of the three priority areas identified in this report because the capabilities of ships far exceed those of autonomous vehicles in many key areas. While there has been rapid progress in development of platforms, as noted elsewhere, sensors needed to make critical measurements are still lacking. Also, power, size, and telemetry challenges limit the number and kinds of sensors that can be deployed from an autonomous vehicle, and few can make the kinds of rate measurements needed for process studies.

TABLE 4.3 Participants Among Science Parties on Expeditions of the Academic Research Fleet

| 2012–2022 | # of Participants |

|---|---|

| Educators/Outreach | 502 |

| Scientist, Postdoc | 475 |

| Student, Graduate | 3,680 |

| Student, Undergraduate | 2,680 |

| Student, K–12 | 32 |

NOTE: More than 1,000 institutions served by the Academic Research Fleet.

CONCLUSION 4.5: Currently and for the foreseeable future, while autonomous observations can augment shipboard measurements and perhaps reduce the length and cost of cruises, they cannot replace ship-based observational capabilities. Prioritization of developing new modes of sensing could reduce future reliance on shipboard measurements.

National Deep Submergence Facility

The National Deep Submergence Facility (NDSF) is a federally funded center based at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, and the assets housed there are considered part of the ARF. The NDSF maintains and operates three deep-submergence vehicles: The human-occupied vehicle (HOV) Alvin, the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) JASON II, and the autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) Sentry. These vehicles are state-of-the-art platforms that enable the U.S. scientific community to study deep-sea processes with the most advanced tools available. Each has unique capabilities. The HOV Alvin is a submersible that can take three persons, as well as a suite of user- and facility-owned sensors and samplers, on a half-day voyage down to 6,500 meters water depth. HOV dives provide the scientists with unequalled visual insights of the deep sea and the capacity to conduct sophisticated experiments that benefit from an untethered vehicle. The ROV JASON II is controlled via tether by a team of pilots and scientists from on board the ship that is operating the ROV. JASON II’s power is provided through the tether so it can stay at depths down to 6,500 meters for days, allowing longer-term studies, experimentation, and extensive sampling. The AUV Sentry is an autonomous robot that can be programmed and deployed to sense and sample down to 6,000 meters. It is a highly capable vehicle used for autonomous mapping and imaging in the deep sea. It is also untethered and can be operated alongside the HOV Alvin.

The NDSF is an integral part of the U.S. oceanographic research infrastructure. It has evolved over the last decade, in terms of both its vehicles and operations. The HOV Alvin was rebuilt in 2014 and was recently upgraded by NSF to allow deployments to 6,500 meters depth. The ROV JASON II was modified several years ago to allow a heavy lifting capability and deployment configurations that make it amenable to being launched off both global- and ocean-class ARF vessels. The AUV Sentry was also recently upgraded to explore greater depths and to have longer-duration deployments and new modes of biological sampling, such as environmental DNA. The NDSF was also a pioneer in launching a “new user program” that facilitated the development of a larger user base. Additionally, the NDSF has worked to streamline the acquisition, curation, accessibility, and archiving of data (including video) collected by its assets to ensure that the data products are of the highest quality and broadly available. Recently, in response to community assessments, the NDSF has received support from NSF to build a smaller, more affordable midsize ROV to meet growing demand, especially in nearshore and coastal environs, which can be deployed from the new, NSF-owned RCR/Vs and other vessels.

Scientific Impact

The NDSF tracks scientific publications and other products associated with the use of its deep-submergence vehicles and has found that they have a marked impact on ocean science. These data are presented annually at town hall meetings. They reveal that the vehicles have played a key role in advancing ocean science in the last decade, including, but not limited to, the discovery of the deepest hydrothermal vents, discovering novel microbes in the deep subsurface biosphere, elucidating biogeochemical processes that support surface primary production, and unraveling the geophysical processes of plate motion. The NDSF has also been a launchpad for many careers, providing engineers and scientists with the opportunity to design and operate leading technologies. The Deep Submergence Science Committee sponsors workshops for early career scientists to acquaint them with the capabilities of the NDSF. Thus, the NDSF has historically contributed to workforce development, although there are opportunities for growth (presented below).

Current Funding Trends

The NDSF is supported primarily through a 5-year cooperative agreement with NSF (other support comes from NOAA, ONR, and other federal and nonfederal sources). Its funding is negotiated annually, based on the number of NSF-funded operating days. From 2014 to 2024, agency funding for the NDSF varied between $10 million and $13 million (depending on vehicle and research vessel refits, operational days, etc.). As is true for the ARF, operating costs have increased because of increases in salaries and cost of hardware and supplies. Moreover, all NDSF vehicles are deployed from research vessels, so increases in their costs have an impact on the overall day rate.

A number of issues have arisen over the last decade that have taxed the facility. In some years, the decreased number of vessels in the ARF, along with sustained demand for deep-submergence vehicles, has meant that some scientists wait 4 or more years to see their expedition realized. This is beyond the life cycle of a funding grant, burdening the scientist and NSF with a series of no-cost extensions, requests for supplemental support, and other administrative minutiae that contribute to inefficiency. There is also a persistent and growing interest in using ROVs and AUVs in the coastal and nearshore environment, but NDSF assets are often oversized for use in these locales and on regional vessels (e.g., the HOV Alvin can be deployed only by the R/V Atlantis). In addition, there are an increasing number of deep-submergence vehicles being operated by commercial, philanthropic, and other government entities. The directorate has, when appropriate, hired commercial operators and partnered with other nations to support global-scale research. U.S. scientists sometimes request these other operators to gain access to their study sites, especially where vessel support is limited geographically, and then turn to NSF to support the subsequent analyses. While this can be an effective model for an individual researcher or team, it is currently done ad hoc and, to the committee’s knowledge, there is no standing policy about NSF’s interest or ability to support such collaborations. Thus, NDSF’s ongoing efforts to develop the midsize ROV need to be supported specifically.

CONCLUSION 4.6: The NDSF provides access to vehicles that are essential for research related to the report’s three science themes listed in Conclusion 2.2. The following enhancements would improve the assets offered to the oceanographic community:

- Expand the array of assets available to users, including lower cost ROVs and AUVs for deployments on coastal and regional vessels (i.e., used in nearshore and coastal regions).

- Expand the scientific footprint of each HOV, ROV, or AUV dive by enhancing remote science capabilities and the inclusion of autonomous assets that can work alongside the vehicles and perhaps be deployed simultaneously.

- Increase access to deep-sea research for early career professionals, by continuing to host workshops for early career scientists, among other activities.

- Enhance international cooperation to enable U.S. scientists to lead global-scale research efforts, including but not limited to supporting the use of commercial, philanthropic, and foreign national deep submergence assets when either it is more cost-effective or when U.S. assets are otherwise committed.

- Develop a formal trainee program that serves the needs of the facility and the greater needs of the maritime science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) workforce.

Supporting a New Decade of Research

Answering all three urgent science questions from Chapter 2 will require extensive use of the ARF (including the NDSF) for process studies and, in some cases, to obtain the necessary ocean observations by deploying moored instruments, AUVs, and ROVs. For example, large shipboard science parties on an ocean- or global-class vessel are required for carbon flux studies, whether they are of the natural system or related to applying marine carbon dioxide removal (mCDR) technologies, because measurements are required of the dissolved carbon system components (carbon dioxide [CO2], hydrogen carbonate, etc.), as

well as the organic phases (both dissolved and particulate). Supporting measurements needed include nutrient pools and their update rates as well as the particulate sinking flux measured with sediment traps, isotopes, and newly developing novel approaches. NDSF vehicles are also important for seafloor studies and deep-ocean studies, including those related to geological extreme events and critical minerals research.

CONCLUSION 4.7: The ARF, including the assets in the NDSF, are the backbone of OCE-funded ocean science research programs and are required infrastructure for addressing the portfolio of urgent ocean research over the next decade. OCE has an important role to play in regaining U.S. leadership in ocean sciences by providing access to the sea with research vessels.

RECOMMENDATION 4.1: The National Science Foundation’s (NSF’s) Division of Ocean Sciences and appropriate partners should conduct an evaluation that details the funding allocation for the Academic Research Fleet in order to make informed distributions of the limited resources available over the next decade and beyond. The evaluation should consider metrics such as days of use funded by NSF; use of local vessels for NSF-funded research; geographic distribution of assets; and alternative mechanisms for providing researchers with access to the coasts (including salt marshes) and sea, such as through marine laboratories or new partnerships.

The long-term status of global-class research vessels is concerning; the committee urges interested parties to initiate and/or continue significant and intentional planning for replacements. Without such planning and subsequent implementation, accomplishing high-priority basic and solutions-oriented science will be compromised, and U.S. leadership in providing access to the ocean will be curtailed.

Ocean Observatories Initiative

The mission of OOI is to provide real-time data in remote places to better understand the ocean, its complexity, and how it is changing because of natural and anthropogenic processes. This mission aligns the three research priorities in this report. Concomitantly, however, there is concern within the broader oceanographic community whether OOI remains the right tool for meeting ocean science objectives in a landscape of limited resources and notable technological innovation. As with other facilities, the committee finds that the community of users and the facility itself has not always been effective at summarizing and communicating their successes nor building a strong sense of community.

The OOI’s stated science objectives are ocean climate variability, ocean food webs, and biogeochemical cycles; coastal ocean dynamics and ecosystems; global and plate-scale geodynamics; turbulent mixing and biophysical interactions; and fluid-rock interactions and the subseafloor biosphere. The committee received briefings on progress towards the objectives from the operators but found it difficult to get a sense of how much the research communities in these fields are engaged with and use the OOI data.

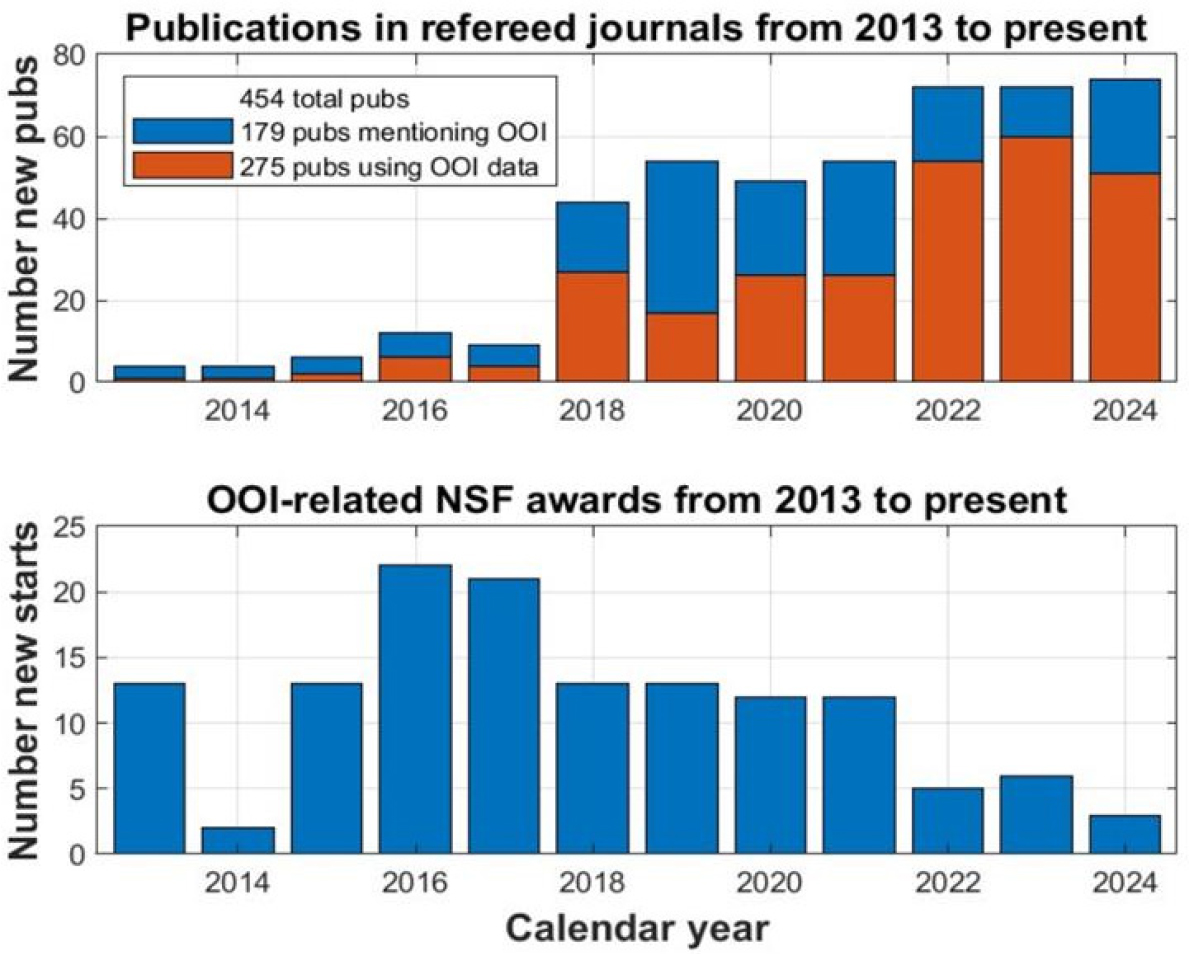

One approach to assessing impact is to look at published papers; however, in curating publications, it was difficult to identify output specifically resulting from the OOI. The OOI website lists over 400 publications that are sorted by observing array rather than scientific discipline. Metrics obtained via searches of the Web of Science and Dimensions databases as reported to NSF found 275 peer-reviewed references that used OOI data or infrastructure from 2013 through 2024. Manuscripts related to geology (primarily using data from the cabled array) and physical oceanography (primarily using the open ocean arrays) were more common than those from the subfields of biological or chemical oceanography. These statistics refer to only NSF-supported research, whereas other U.S. federal agencies such as NOAA and ONR, as well as non-U.S. agencies, such as the UK’s Natural Environment Research Council, also support research using OOI infrastructure and data, and even if specifically ingesting OOI data, do not always cite OOI as the data source.

The number of OOI-related NSF awards from the core science programs (as distinct from the cooperative award to operate the OOI itself) peaked in 2016 (22 awards) and declined in subsequent years (3 awards in 2024), whereas the number of publications citing NSF support has increased since 2013 to more than 70 publications in 2024 (Figure 4.4). The OOI Facilities Board suggests that this trend is related to the freely available OOI data regardless of supporting agency and the use of funding sources other than NSF to analyze these data.

Enumerating publications is only one measure of determining OOI research contributions. Specifically, numbers of resulting manuscripts do not necessarily correlate with scientific impact—for example, one key manuscript can have a disproportionate scientific impact. However, it is clear that publications using and mentioning OOI data are continuing to grow, and continued growth in use of the data may help justify the investment of resources and funds.

Education and outreach are other areas that can be used to measure impact. Since 2018, OOI has expanded its reach through social media, adding thousands of followers on LinkedIn, Instagram, X (Twitter), and Facebook. The OOI Facilities Board documented a large number of education and workforce development activities using OOI data in the United States and elsewhere at the high school, undergraduate, and other higher education levels. These are encouraging trends.

Nevertheless, it would be advantageous for the OOI operators and community to consider whether and how they are serving the needs of the broad interdisciplinary fields they seek to serve. NSF needs to consider a careful evaluation of the facility in the context of this report and OOI’s stated science objectives, as described below.

SOURCE: OOI, 2025.

The committee’s review of the OOI revealed a program that has many operational successes and strengths (Box 4.1) but also scientific gaps and a wider lack of coherence relative to the needs of the ocean science community. In the past decade, the OOI has worked out many of the programmatic aspects of the deployment and recovery of instruments and the support required to enable real-time services. These successes can be demonstrated in improved data collection and data reliability and some growth in publications arising from the instrument deployments.

The origins of what is now OOI began over 20 years ago, and the agency was initiated approximately a decade ago, when the needs for observations and the technological opportunities were much different than they are now. While the OOI’s Implementation Organizations and the Program Management Office have kept up with technological innovation admirably, the overall fundamental premise of large, fixed assets as a research backbone may need to be reevaluated, given the changing state of ocean observations and framed in the context of the needs outlined in this report. Other approaches to ocean sampling (e.g., spatial sampling in extreme events such as hurricanes) also need to be considered, which could offer partnership opportunities to extend the footprint of observations and significantly enhance the adaptive sampling capacity. Such applications are being developed (e.g., using gliders to sample circulation patterns in the Pacific Ocean or in the path of hurricanes in the tropical Atlantic). Other complementary approaches should be considered for inclusion in the OOI, some of which are already underway, such as the use of SMART cables, distributed acoustic sensing, widespread ocean gliders, uncrewed surface vehicles, and more.

Some aspects of the OOI are very much aligned with the three priorities of this reports. For instance, the recently funded Cascadia Region Earthquake Science Center cable will monitor the unlocked portion of the Cascadia Subduction Zone, improving early warning and understanding of risk for extreme events; the long-term oceanographic data collected in the Irminger Sea is a critical site for understanding and forecasting changes in Atlantic meridional overturning circulation; the air–sea interaction measurements made with large open ocean buoys are relevant to the question regarding carbon and heat exchanges between the ocean and atmosphere; and coastal data provide vital context to important ecosystem and fisheries changes, from acidification to ocean heat waves to algal blooms. Nevertheless, a fixed system will never meet the extent of needs; consideration of the current OOI network in the broader context of nested observations—with careful thought to what is working, where gaps exist, and cost-benefit analysis—is needed.

CONCLUSION 4.8: Although the OOI program has enabled new discoveries, such as important seafloor and seismic processes around the Axial Seamount, and episodic events related to the Gulf Stream or the California Current system, there is a disconnect between the established program, the science achieved, and the current and future needs of the ocean science community broadly.

Supporting a New Decade of Research

The OOI, as it stands, would partially support the urgent research questions for the next decade. The cabled array component of OOI supports the research of extreme geological events, such as those that occur in the tectonically active zone off Oregon and Washington, and has the potential to collect additional oceanographic data, particularly using distributed acoustic sensing tools. There is every reason to believe that data from the array will continue to support research in the next decade. NDSF resources will be used to deploy and retrieve instrument packages to measure crustal strain and stretch. The deep ocean buoys in the Irminger Sea and at Station Papa, which focus on collecting data on air–sea exchange, climate, and the carbon cycle, provide insights into mechanisms governing heat and CO2 uptake, and a better understanding of those processes, particularly under high wind regimes. When conducted near their locations, mooring and glider measurements at the Pioneer and Endurance arrays will provide key supporting measurements for process studies related to all three high-priority research questions. The Pioneer and Endurance arrays have also provided critical documentation of oceanographic extreme events related to ocean warming, changes in ocean circulation along the continental shelf in areas critical to commercial fisheries, and other processes operating over short timescales. Intentionally aligning future goals and capabilities of the OOI

program with the needs of the ocean science community broadly and with the urgent science questions described in Chapter 2 would further increase the use of this major facility.

BOX 4.1

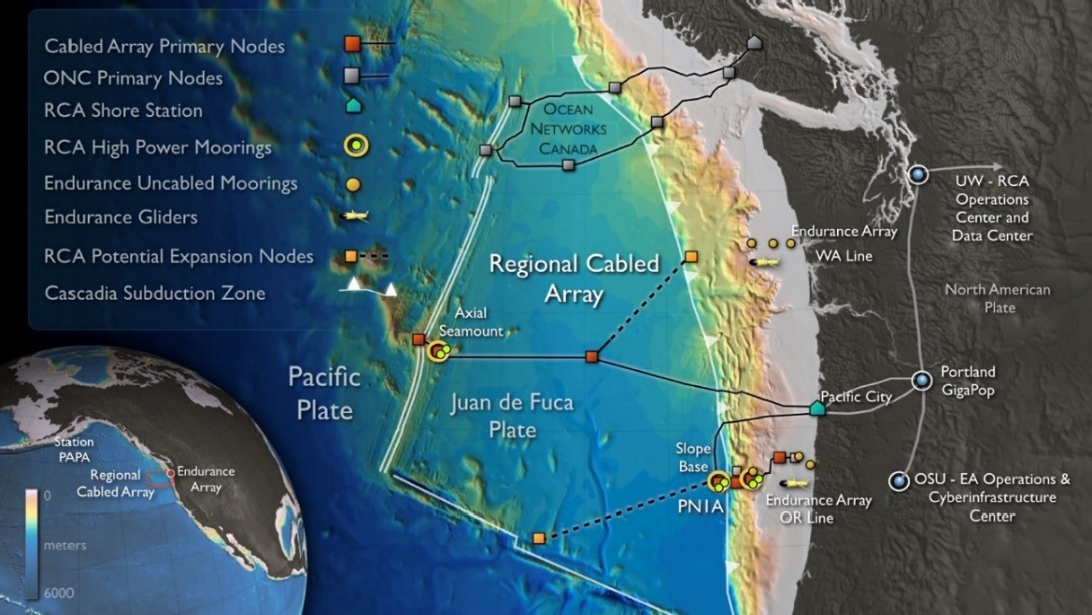

Ocean Observatories Initiative (OOI) Captures Submarine Eruption for the First Time

Axial Seamount hosts the most advanced submarine volcanic observatory in the ocean. A suite of 20 core OOI regional cable array instruments (Kelley et al., 2014) at the end of ~300 miles of cable links this most active submarine volcano off the Oregon–Washington coast to the internet (Kelley et al., 2015; Figure 4.5). In April 2015, only months after these instruments came online, Axial Seamount erupted just 4 years after its last eruption. Miraculously, the cable and instruments were undamaged, and the data collected provided multiple insights into volcanic eruptions and early warning signals that are applicable to both terrestrial and submarine volcanoes.

Increased seismicity, inflation, tremor, and tidal triggering preceded a seismic crisis associated with the eruption, which also led to the detection of an impulsive signal associated with lava erupting on the seafloor (Wilcock et al., 2016). Tilt and bottom pressure measurements detected deflation 1.5–2 hours after the start of the seismic crisis (Nooner and Chadwick, 2016), and approximately 1.5–2 hours after that, northward migration of some ~37,000 impulsive events signaled propagation of the dike along the north rift, ending with the eruption of a ~127-meter-thick lava flow (Kelley et al., 2015). Approximately a week after the start of the eruption, a series of diffusive broadband signals from 2 to 60 minutes in length were recorded and a significant increase in water temperatures near the floor of the caldera were recorded, coincident with an onset of diffusive activity (Caplan-Auerbach et al., 2017). Overall increases in bottom water temperature began 3 days after the start of the eruption and lasted for ~40 days (Xu et al., 2018). The increased temperatures are interpreted to reflect the emission of warm subsurface brines derived from the boiling hydrothermal systems at Axial (Xu et al., 2018). Monitoring of the caldera since the eruption shows direct linkages between changes in the inflation rate and seismic activity, and the volcano has inflated 90–95 percent since its last eruption (Chadwick et al., 2022). Current forecasts, updated near daily place the next eruption to occur between now and December 2025. Following lessons learned from the 2015 eruption, it is expected that a significant increase in seismic activity will predate this event, which has been observed since early 2024. The increased understanding of eruption precursors and signals is not only important for the Axial eruption; it has also led to the reinterpretation of a 2006 eruption along the East Pacific Rise (Tan et al., 2016), the timing of which had long been debated.

NOTES: ONC = Ocean Networks Canada; OSU-EA = Oregan State University–Endurance Array; RCA = Regional Cabled Array; UW = University of Washington.

SOURCE: University of Washington.

RECOMMENDATION 4.2: The National Science Foundation’s Division of Ocean Sciences (OCE) should conduct a revisioning and restructuring exercise for the future of the Ocean Observatories Initiative (OOI). The review, which should occur as a fully separate activity from the usual renewal/recompete discussions, could include:

- an analysis of the scientific contributions of each of the OOI arrays;

- reconsideration of the goals and objectives of the program to better address the needs of the ocean science community and align with the evolving and urgent ocean science questions for the next decade; and

- consideration of how to incorporate technology that may not have existed when OOI was originally envisioned, including innovative ways to observe and measure biological abundances and processes, such as low-cost distributed observational networks.

This recommended review differs from, and should be independent of, the renewal process that is focused on how well the infrastructure is meeting the requirements of the existing cooperative agreement. Rather, this investigative approach would provide a timely path forward for the next iteration of OOI that takes advantage of strategic partnerships, the evolution of ocean sciences and technological capabilities over the two decades since the OOI was originally conceived, and the approaches needed to address the urgent research priorities laid out in this report, as well as other science questions. This recommended review should occur well before the initiation of the review/renewal discussion regarding the current cooperative agreement.

Ocean Drilling Program

The United States has been the leader of international scientific ocean drilling for decades. During the second International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP-2) (2014–2024), 95 percent of all cores recovered were drilled by the U.S.-operated JOIDES Resolution, compared with only 4 percent with the European-contracted mission-specific platform approach, and only 1 percent with the Japanese drilling vessel, the Chikyu (see Table 1.1 in NASEM, 2024b). The United States was also the leader in expedition-related research publications, with more peer-reviewed journal articles between 2003 and 2021 than any other country (Figure 2.7 in NASEM, 2024b). Additionally, the United States was a global leader in achieving gender balance and in providing opportunities for students and early career researchers in ocean-going expeditions: since 2020, there were more U.S. women sailing on expeditions than men, with one-half of the expeditions led by women chief scientists; and there were equal proportions (one-third each) of graduate students, early career researchers, and senior researchers, on U.S.-operated expeditions during IODP-2 (Box 2.2 in NASEM, 2024b). These examples of leadership resulted from a uniquely capable infrastructure; a ready U.S. scientific workforce; and a culture of scientific excellence, mentoring, and collaboration (NASEM, 2024b).

As the majority funder of the JOIDES Resolution, providing $48 million per year through a cooperative agreement with Texas A&M University, NSF can take credit for much of this success. Rising costs, flatlined U.S. program funding, and a decrease in international partner contributions (from $16.5 million in fiscal year [FY] 2015 to approximately $5 million for FY2024; Figure 4.6) have contributed to a crisis in scientific ocean drilling that specifically and seriously threatens the future of U.S. leadership, U.S. scientific workforce development, and the advancement of ocean sciences overall. With the 2024 demobilization of the JOIDES Resolution, which was the only U.S. dedicated vessel for scientific ocean drilling and the only U.S. vessel capable of coring deeper than 50 meters into the seafloor, it is estimated that at least 90 percent of current scientific ocean drilling objectives identified in the 2025 Decadal Survey interim report will not be met (NASEM, 2024b). These unmet drilling objectives include those integral to address the three urgent priorities for ocean science research over the next decade: ocean and climate, ecosystem resilience, and extreme events (see Chapter 2 of this report).

SOURCE: IODP, 2024, p. 7.

In order to successfully emerge from this crisis, a reenvisioned, sustainable U.S. scientific ocean drilling program needs to be defined, funded, and managed so that it can (1) maximize the scientific value of legacy assets (e.g., cores, data) already collected from scientific ocean drilling, (2) meet the need for long-term replacement of globally ranging deepwater drilling capabilities, and (3) encourage collaboration and fair international partnerships.

A pilot concept for multiyear, expedition-scale Legacy Asset Projects (LEAPs)—proposed by the IODP JOIDES Resolution Facility Board and currently managed by the IODP Science Support Office—was described in the interim report (NASEM, 2024b). A dedicated funding line at NSF for LEAPs would better incentivize the use of existing cores and create a funding structure for supporting it. Funding the LEAPs program will support basic ocean science research using existing cores, foster discovery and innovation, and create a mechanism to at least partially support and maintain a ready U.S. workforce for future scientific ocean drilling. However, without dedicated NSF funding, the LEAPs program will not facilitate future research as well as it could. The committee believes a funded LEAPs program, similar in funding level to the IODP-3 Scientific Projects Using Ocean Drilling Archives program ($1–2 million/year; Camoin and Eguchi, 2024) is a great approach to maximizing the scientific value of legacy assets and complementing new cores collected. A committee, including ocean drilling scientists, that makes sample allocation decisions would be an important part of a funded LEAPs program.

With respect to item (2), both short- and long-term strategies are needed. There is an immediate need to explore options for a sustainable drilling program involving a single U.S.-operated drillship, either newly constructed or leased. The outcomes of the current Subcommittee for a New Scientific Ocean Drilling Platform, formed by the NSF Advisory Committee for Geosciences, provide needed information on the estimated costs and the capabilities necessary to support the urgent research priorities in this report and in the 2024 interim report. A sustainable, long-term scientific ocean drilling program may benefit from reintro-

ducing the option for complementary project proposals (CPPs) and nurturing/developing options for industry collaboration using the U.S.-operated drillship, with the goal of maintaining an additional, sustainable funding stream to supplement NSF funding for science operations. Extra funding generated from an industry-based expedition in 2012, and from CPP contributions from interested partner countries in early IODP-2 (Figure 4.6), may be models to expand in the future. On the other hand, international participation in the original Ocean Drilling Program (which ended in the early 2000s), including partial funding of JOIDES Resolution operations, worked more successfully than the later various IODP-named programs; key aspects of that earlier model could be reconsidered. Additionally, as outlined in the interim report (NASEM, 2024b), different management and operational approaches may be needed to balance financial constraints with needed shipboard versus shore-based measurements, staffing to support operations (prior to, during, and after expeditions), and advisory structures for safety and scientific purposes.

In the short term, until a dedicated drillship is available, NSF needs to continue supporting the use of mission-specific platforms for addressing high-priority, urgent science questions. As identified in the interim report, the JOIDES Resolution, now no longer under long-term NSF contract, could be considered a mission-specific platform, possibly for an extended period involving multiple expeditions over several years. Nevertheless, the committee sees U.S. and international mission-specific platforms as a “bridge solution” because one-off mission-specific platforms are logistically challenging in terms of securing vessels, engineering, and technical expertise, and are thus expensive and do not alone meet the identified science objectives (NASEM, 2024b).

Finally, collaboration among scientists from different countries, disciplines, and career stages has been a hallmark of scientific ocean drilling for decades. Collaborative science is better science, and this principle remains true as the committee seeks a blueprint for the future of scientific ocean drilling. As NSF and the U.S. and international scientific community work to emerge from the current crisis, this principle needs to remain an anchor in deliberations on the next steps.

CONCLUSION 4.9: The interim report (Progress and Priorities in Ocean Drilling: In Search of Earth’s Past and Present) includes many conclusions related to the future of scientific ocean drilling. Following the release of this report, OCE took several important steps towards planning for a future dedicated vessel with globally ranging scientific ocean drilling capabilities, as well as steps towards securing future mission-specific platforms for the ocean drilling community to use in the nearer term. OCE also committed to continue preserving and curating ocean drilling legacy assets (cores, samples, and data). Retaining the ability to support (financially and otherwise) U.S. scientists pursuing scientific research using new and archived ocean drilling assets remains critical to basic research and to the urgent ocean science research portfolio identified this report. Nonetheless, because of the decommissioning of the JOIDES Resolution, there will be substantive and significant unmet drilling objectives that are integral to addressing the three high-priority research questions identified in this report.

Supporting a New Decade of Research

The 2025 Decadal Survey interim report on scientific ocean drilling, Progress and Priorities in Ocean Drilling: In Search of Earth’s Past and Future (NASEM, 2024b), identified three vital and urgent themes related to the three science questions discussed in Chapter 2:

- Ground-truthing climate change: Advancing understanding of climate and ocean change drivers, feedbacks, and past tipping points.

- Evaluating past marine ecosystem responses to climate and ocean change: Fossils can be used to determine ecosystem responses to ancient environmental changes, including warming, ocean acidification, and deoxygenation. This understanding of the past can be used to better understand the way that current, rapid environmental changes over decades generate ecosystem change.

- Monitoring and assessing geohazards: Providing data to more accurately forecast and assess future risks of earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, submarine landslides, and tsunamis.

These three urgent and vital priority areas for a future scientific ocean drilling program align with, and are integral to, research over the next decade that is needed to address the three urgent ocean science questions identified by this committee. Additionally, while not described as urgent in the interim report, several other vital areas of research were listed. For example, scientific ocean drilling of the ocean crust (basalts) has yielded frontier research into the nature of the deep microbial biosphere and has provided foundational evidence on the evolution of the oceanic (and continental) crust and its role in the long-term geochemical cycling of elements. Research on the subseafloor biosphere has direct implications for understanding the potential for life in other areas of the solar system, the origins of life on Earth, and the integral building blocks of ecosystems that nurture the biological world. This research is also necessary for identifying potential environmental effects from the harvesting of critical minerals from the seafloor. The cycling of fluids through the subseafloor and corresponding chemical exchanges between the liquid and solid earth may impact processes with direct societal relevance, including the production of mineral resources, sequestration of atmospheric CO2, and origin of geohazards (including volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, and related tsunamis). These are discussed in greater detail in the interim report (NASEM, 2024b).

CONCLUSION 4.10: Research utilizing scientific ocean drilling plays a unique and important role in addressing the urgent science priorities:

- Ocean and Climate: How will the ocean’s ability to absorb heat and carbon change?

- Ecosystem Resilience: How will marine ecosystems respond to changes in the Earth system?

- Extreme Events: How can the ability to forecast extreme events driven by ocean and seafloor processes be improved?

The assets that will be available for scientific ocean drilling for the next decade are not yet known. In the past, by deploying sophisticated instrument packages in boreholes and in other ways, scientific ocean drilling has made significant contributions to understanding earthquakes and other extreme seafloor events. Furthermore, analysis of cores collected throughout the global ocean have documented changes in ocean carbon cycling, times of rapid warming and extreme heat, and identified periods of significant ecosystem changes related to the biology, chemistry, and physics of the ocean, such as past periods of extensive deoxygenation and ocean acidification associated with ocean and atmospheric warming. These studies provide insights into the impacts of a future warming planet. This research may continue in the future using the extensive archive of cores previously collected but also depends on new cores from future drilling operations. Without new approaches to addressing both legacy assets and infrastructure needs, the capacity for future U.S. operational and scientific leadership is bleak. It is unlikely that such U.S. leadership can be regained without a U.S.-based drillship.

RECOMMENDATION 4.3: The National Science Foundation (NSF) should take action to regain U.S. leadership in scientific ocean drilling on a global stage. To support basic ocean science and the urgent ocean science research portfolio identified in this report for the next decade and beyond, the committee makes the following recommendations:

- Legacy assets: NSF’s Division of Ocean Sciences (OCE) should create a dedicated funding line for the Legacy Asset Projects program to support expedition-scale collaborations, which maximize the return on legacy assets by providing funding to scientists to conduct large-scale research with existing cores and data.

- New drilling infrastructure:

- OCE should develop a sustainable ocean drilling program, taking into account the need for a U.S.-based drillship. The committee urges NSF to creatively implement management and operational models that ensure viable long-term operations of such a vessel, including developing and nurturing more options for industry work. Such new management and operational models may differ significantly from the recently concluded drilling program.

- Until a dedicated drillship is available, OCE should continue to support the use of mission-specific platforms for addressing high-priority, urgent science questions, and to the extent possible, support efforts to retain the technical and engineering expertise in deep-sea coring previously employed by the United States with the JOIDES Resolution.

- International collaboration and coordination:

- NSF and international funding agencies and governments should coordinate and collaborate globally toward an integrated, long-term strategy for scientific ocean drilling. Such collaboration will require meaningful and transparent reciprocity in scientific participation levels, financial support, scientific planning, and more among contributing partners.

- OCE should renew dialog with both new and long-standing international partners to identify cost-sharing models for dedicated drillship operations; such models may include scientist shipboard participation proportional to international contribution levels.

SUPPORTING INFRASTRUCTURE

Oceanographic Institutions and Local Research Vessels

Oceanographic institutions support NSF-funded research in many ways, including by supplying research vessels and access to marine laboratories and stations. For example, the ARF is not the only mechanism for providing ship time, and the vessel usage described in Table 4.2 is an incomplete picture; however, the committee did not have information as to how much other NSF-funded research is conducted on board vessels that are not part of the UNOLS-coordinated ARF. Tracking the amount of OCE-funded research taking place on smaller vessels, such as those operated by the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (College of William and Mary), The University of Southern Mississippi, and Florida State University, would clarify the contributions of these vessels to the OCE research portfolio. This analysis would be timely, as all the local- and coastal-class vessels in the ARF will reach end-of-life by the end of the decade. This suggests NSF-sponsored research in estuaries, bays, and coastal waters may have to rely more heavily on local vessels that are not currently in the ARF.

The committee attempted to conduct an informal review of institutions operating outside of UNOLS to provide days at sea in coastal waters on the Pacific, Atlantic, and Gulf Coast. The aim of this effort was to obtain an understanding of how much NSF-supported science was occurring on board these vessels. The response rate for this inquiry was low, however, probably hampered by a lack of knowledge by the vessel operators of the funding sources of those that come on board to conduct research. Some institutions reported the affiliation of scientists on board or the research activities that took place, but information on how NSF was using these ships to support funded research could not be derived from their responses.

CONCLUSION 4.11: Evaluation metrics, such as days of use funded by NSF on non-ARF local vessels reported by the ARF community, would be helpful to OCE for making informed allocations of the resources available.

Marine Laboratories and Stations

U.S. marine laboratories and stations constitute a large, diverse, and critical element in U.S. ocean science, teaching, and infrastructure investment. As discussed in Chapter 3, 99 labs are members of the National Association of Marine Labs, situated in 36 states and territories. The labs have access to unique and important marine research areas in the Pacific, Gulf, Caribbean, Atlantic, and Great Lakes (Figure 4.7). NSF supports a specific Field Stations and Marine Laboratories infrastructure improvement program, and about half of marine labs received funding from this program during the last 15 years.

NOTES: Most labs are in coastal North America, with some in the tropical Pacific and Caribbean.

SOURCE: National Association of Marine Laboratories.

In addition to the vessels described above, marine laboratories and stations contribute to the infrastructure supporting NSF research by:

- providing small boats for research related to coral reefs, coastal wetlands, and estuaries;

- providing the space and flowing seawater systems to support experiments requiring tanks and aquaria for research projects;

- purchasing ship time on the ARF fleet to support research and education activities;

- supporting research library buildings, collections, and personnel;

- absorbing the construction costs of docks and piers;

- providing personnel, as well as vehicles and other equipment, to support loading and unloading operations;

- cost-sharing with NSF for large and expensive scientific instruments, such as mass spectrometers;

- providing space to store rock and core samples, and benthic and pelagic organism collections;

- providing storage space for field gear, as well as shipboard equipment, such as winches, and;

- collecting, curating, and storing coastal data on a long-term basis.

Research, training, outreach, and community connections at the U.S. marine stations are vital to support the three research priorities outlined in Chapter 2. First, integration of physics, chemistry, and biology is a key feature of the report, and this mix is relevant to the climate change work going on in coastal zones, particularly at U.S. marine labs. Second, of central interest to marine labs is integrating physical and chemical models into ecosystem processes, a line of research that is highly relevant in the coastal ecosystems of bays, estuaries, marshes, and sea grasses that are nearby many marine stations. Third, long-term ecosystem and ocean stability is key to understanding extreme events, and studying these is particularly cost-effective in coastal areas. As a result, the constellation of marine stations represents on-the-ground facilities that help stage ocean and ocean-life research across the country.

As described in Chapter 3 (Box 3.5), marine stations are also well suited to support development of the broad, transdisciplinary research that was the focus of Chapter 2. The stations themselves are often part of a local community and can help integrate local, Indigenous, and traditional knowledge in research and education. In these ways, the marine stations are major conduits to progress in components of the 2025 Decadal Survey.

CONCLUSION 4.12: Marine laboratories, marine stations, and oceanographic institutions make significant contributions to the infrastructure and workforce supporting OCE-funded research; financial and administrative attention is needed for their continued support.

Autonomous Platforms

Recent years have been a watershed for the development of AUVs, autonomous surface vehicles (ASVs), and gliders (ultra-low-power AUVs). In the past decade, legislation supported collaborative development of these technologies among federal agencies (i.e., NOAA) and industry (Commercial Engagement Through Ocean Technology Act of 2018) to advance the pace of autonomous operational capabilities. This is a strong indication of support for the widespread development and potential use cases for these technologies. A quick search of Google Scholar4 reveals that in 2014, there were 2,380 publications on ocean AUVs. By 2024, the number of publications had more than doubled to 6,310. Publications with ocean gliders rose by over 40 percent in that time frame. The U.S. ocean sciences community has been at the leading edge of developing these marine autonomous technologies, and they are in use at a wide array of institutions (although the usual disparities still exist, with better-funded institutions having greater access to these assets). Furthermore, the proliferation of low earth orbit satellites such as Starlink can vastly improve communication and telemetry from AUVs.

Measurements from autonomous vehicles and floats will be critical for research related to the three high-priority science questions (Table 4.1). Research using autonomous platforms falls within two general categories: (1) sustained observations using vehicles or floats, such as gliders; and (2) vehicles and floats to extend the profile of oceanographic ships for studies of ocean processes. Both types of applications are essential to future ocean sciences research, and use of the latter will likely grow in popularity in the future.

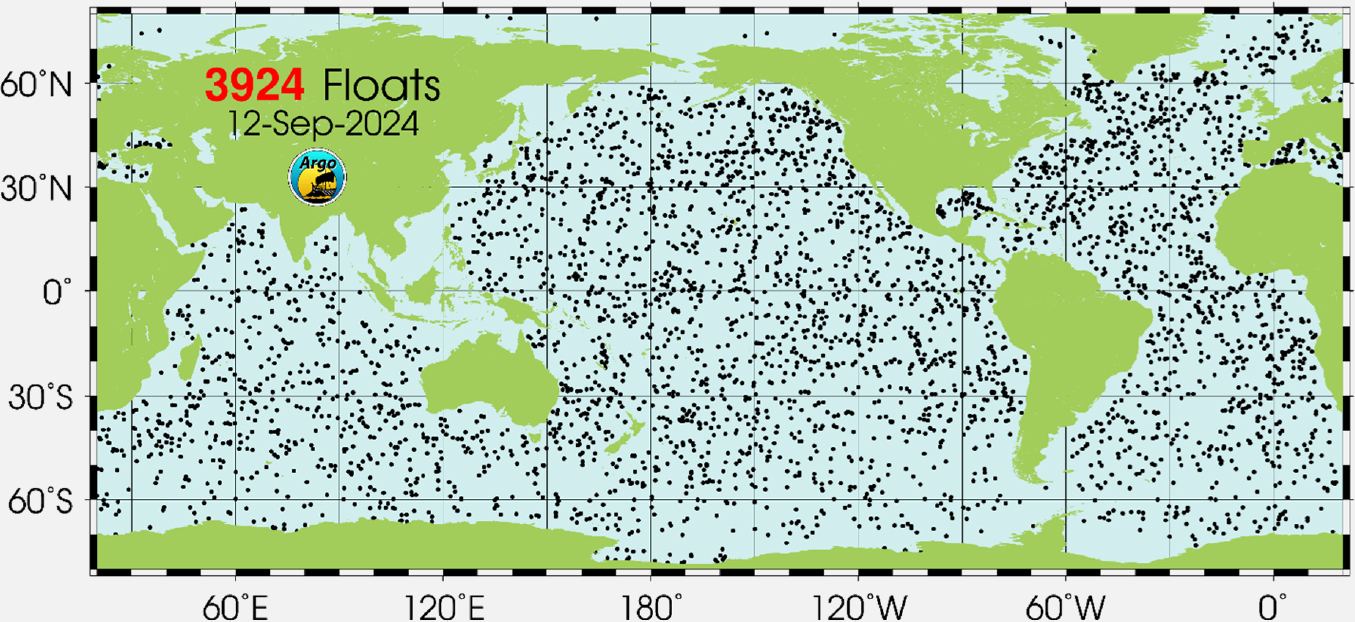

Sustained Observations Using Vehicles or Floats

The Argo program provides global measurements of heat content in the upper 2,000 meters (Box 4.2), and new Argo floats will have the capability to make those measurements in waters deeper than 2,000 meters (Roemmich et al., 2019). At present, the Argo program is critical for collecting data to determine how much heat the ocean absorbs and how the accumulated heat spreads across ocean basins at the global scale, and for providing data to support forecasts of future trends in ocean heat content. Although the Argo measurements related to biological processes (referred to as biogeochemical [BGC]-Argo) are not fully mature, they indicate phytoplankton biomass, particulate organic carbon, and attenuation with depth of solar radiation. An NSF-funded Science and Technology Center has provided multiple BGC-Argo floats for deployment in the Southern Ocean. These are important supporting measurements for studies related to ecological resilience and also for providing background variability of particulate organic carbon essential for validating and mCDR approaches. To the committee’s knowledge, funding for BGC-Argo expires in 2025, and the future of this program is unknown.

CONCLUSION 4.13: The Argo program serves as the main source for collecting critical observations of the ocean’s interior. OCE’s continued role in the national and international partnerships that support and enhance the Argo floats, particularly BGC-Argo, will be essential to addressing the urgent ocean science research questions of the next decade.

___________________

BOX 4.2

The Argo Program

The Argo program celebrated its 25th anniversary in 2024; this program provides sustained observations based on a network of autonomous profiling floats—more than 3,900 are deployed as of 2024 (Figure 4.8). The original floats profiled the upper 2,000 meters measuring temperature and salinity at 1–2 meters resolution during a 10-day cycle. Next-generation floats can now profile into deeper waters, and the biogeochemical (BGC)-Argo floats also measure pH, oxygen, nitrate, chlorophyll (from fluorescence), particulate organic carbon (from particle backscatter), and water clarity (from solar irradiance change with depth) in addition to temperature and salinity. Additionally, some floats have been instrumented with passive acoustic listening sensors, which can be used to estimate rainfall rate and wind speed (Yang et al., 2015). New floats with particle imaging sensors are being deployed to identify and quantify zooplankton. During the period of the 10-day cycle when the Argo floats are at the surface, data are transmitted via the Iridium satellite network to data centers.

Argo has provided more than 2 million temperature and salinity profiles in the global ocean, far exceeding the number of such profiles available prior to Argo program. More than 6,000 publications used Argo measurements to:

- determine ocean excess heat uptake,

- determine the warming effect to sea level rise,

- improve calculations of ocean carbon dioxide (CO2) uptake with seasonal resolution,

- determine effect of storms for enhanced CO2 uptake,

- improve understanding of global ocean acidification, and

- determine monthly changes in global oxygen and particulate carbon as indicators of ecosystem productivity.