Bridge and Tunnel Strikes: A Guide for Prevention and Mitigation (2025)

Chapter: 1 Introduction

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

1.1 Defining a Bridge or Tunnel Strike

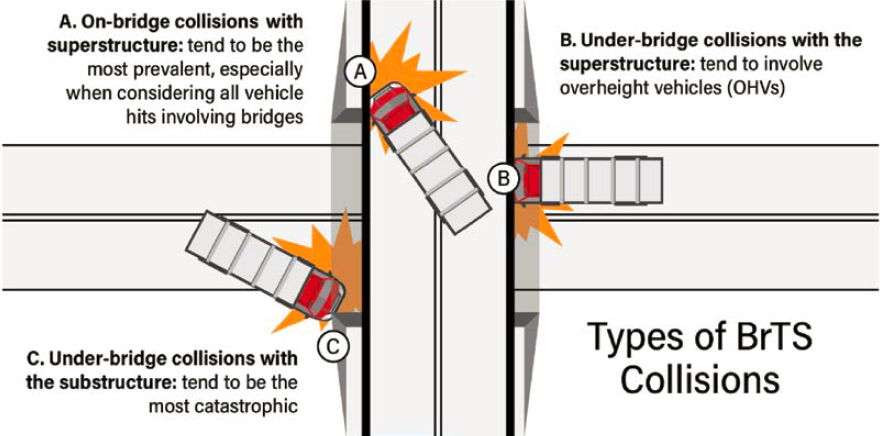

A bridge or tunnel strike (BrTS) is an incident in which a vehicle collides with a bridge or tunnel. More specifically, a BrTS can be defined by the type of bridge or tunnel (e.g., highway, railway, or pedestrian bridge) and the component of a bridge or tunnel struck by a motor vehicle (e.g., girder, truss, rail). Classifying BrTS by type and component is crucial for identifying the source of risks, evaluating the impacts, and identifying appropriate mitigation measures. Figure 1 illustrates three types of collisions: (A) on-bridge (or in tunnel) collisions with superstructure, (B) under-bridge (or entering tunnel) collisions with the superstructure, and (C) under-bridge (or entering tunnel) collisions with substructure. Type A, on-bridge collisions with the superstructure (e.g., railing), tends to be the most prevalent, especially when considering all vehicle hits involving bridges. Type B, under-bridge collisions with superstructure (e.g., girder, truss), tends to involve overheight vehicles (OHVs). Type C, under-bridge collisions with the substructure (e.g., supports), tends to be the most catastrophic. While tunnel crashes can be difficult to identify from crash datasets (see Section 1.3 for further discussion), most tunnel collisions are similar to Type B (under-bridge collisions with superstructure) or Type C (under-bridge collisions with substructure). This guide limits the discussion of tunnel collisions to the tunnel entrance and combines those entrance crashes with under-bridge collisions (Type B or C) as appropriate. This guide also focuses on BrTS involving heavy vehicles, especially OHVs, because of their significant impact on a bridge or tunnel. For this guide, OHVs are defined as vehicles and loads beyond legal size limitations or standard-size vehicles beyond a local height limitation of a specific bridge or tunnel.

1.2 Magnitude of the Issue

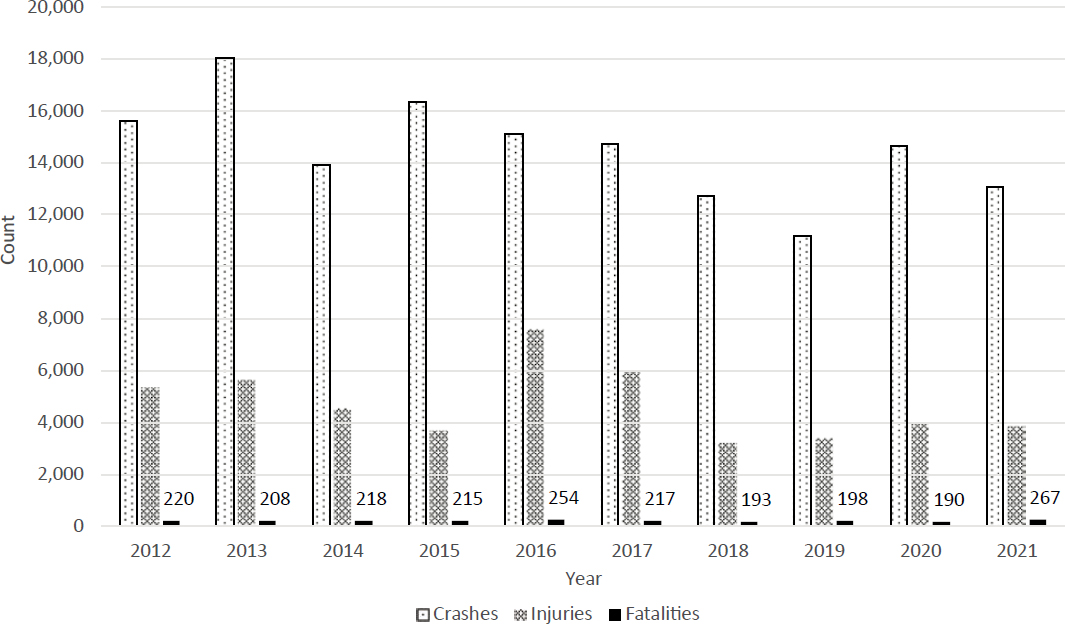

BrTS crashes damage infrastructure, damage vehicles and cargo, create traffic delays, disrupt access to communities, and kill and injure people. Nationally, the number of bridge crashes alone averages more than 14,500 per year (NHTSA 2022). Research has shown that crashes are among the most common causes of bridge failures (Wardhana and Hadipriono 2003; FHWA, n.d.-e; Lee et al. 2013; Cook 2014). As shown in Figure 2, the number of crashes where the first harmful event is coded as “Bridge Pier Or Support, Bridge Rail (includes Parapet) or Bridge Overhead Structure” (listed in the key as “crashes”) ranged from approximately 11,000 to 18,000 crashes per year between 2012 and 2021. These collisions resulted in nearly 2,200 deaths and an estimated 47,000 injuries during the same time period.

Beyond the death and injury toll, BrTS result in millions of dollars of damage to the infrastructure. In Virginia alone, repair costs from BrTS are approximately $4 million per year (Bergal 2019), while in Texas, the repair costs from BrTS are nearly $7 million per year.

It is in our national interest to sustain a dynamic and growing economy and transportation—especially heavy tractor-trailers carrying equipment and goods over the nation’s roadways. As truck volumes increase, including oversize and overweight loads, the burden on our nation’s transportation infrastructure grows. Further, if crash rates hold steady, the increase in heavy truck traffic will lead to an increased number of crashes. Yet even now, when transportation agencies have technologies ranging from unmanned vehicles to transportation automation and big data, they still seek better ways to prevent BrTS by motor vehicles and to mitigate outcomes when they occur.

Motor carriers also have a vested interest in BrTS mitigation. For motor carriers, a BrTS has the potential to result in insurance increases, safety rating drops (FMCSA, n.d.), operator termination, and direct responsibility to pay for the cost of repairs. BrTS can contribute significantly to insurance costs for motor carriers, especially if they result in damage to the truck, the load being carried, a bridge, or other vehicles involved. Insurance costs for motor carriers are influenced by various factors, including the frequency and severity of crashes, the safety record of the company, the type of cargo, driver history, and the specific insurance coverage. BrTS can lead to expensive claims for property damage and bodily injuries and fatalities, which may lead to increased insurance premiums for the trucking company. If a trucking company has a poor safety record (i.e., a history of crashes involving bridges and tunnels), insurance providers may consider them a higher risk, leading to further increases in insurance costs or even dropping the trucking company altogether. Although these costs to motor carriers are intuitively high, data are not currently available to quantify the magnitude of these costs.

1.3 Challenges Mitigating BrTS Risk

Transportation agencies and motor carriers are working hard to mitigate BrTS risk. Transportation agencies invest in operational, infrastructure, and technology strategies to reduce the likelihood and consequences of BrTS. Motor carriers invest in safety training for their drivers, implement technologies like global positioning systems (GPS) and collision avoidance systems, and maintain their vehicle fleet. Despite these efforts, there has been limited success in mitigating BrTS risk due to the following primary factors:

- Challenges in identifying priority locations.

- Challenges in diagnosing the contributing factors.

- Challenges in implementing mitigation strategies and enforcing policies.

Challenges in identifying priority locations: There is a need to first identify priority locations. Traditionally, agencies have used crash history to prioritize bridge and tunnel locations for further investigation and potential treatment. The challenge with using crash history is that BrTS crashes may not cluster at a single location but are spread across the network. This can lead to issues related to small sample sizes when analyzing specific locations. To further compound the sample size issue, there is substantial underreporting of BrTS crashes (Nguyen and Brilakis 2016; Nguyen 2018; and Middleton et al. 2012). There are also data quality issues related to BrTS crash data, including the accuracy and completeness of location coding, contributing factors, and BrTS impact points (e.g., girder, abutment, railing). This makes it difficult to accurately assign a given crash to a specific bridge or tunnel and to diagnose the factors that contribute to a crash. While bridge-strike reporting is generally poor, tunnel-strike reporting is even worse, partially because tunnel strikes may not be identifiable from the crash data as tunnel strikes are categorized as “OTHER” fixed objects.

Challenges in diagnosing contributing factors: Once agencies have identified priority locations, analysts can diagnose the underlying crash contributing factors. The complexity of diagnosing BrTS crashes is related to the potential number and diversity of factors involved (e.g., roadway characteristics, bridge or tunnel characteristics, driver and human factors, and vehicle and load factors). Some of these factors are location-specific (e.g., roadway and bridge characteristics), while others could occur randomly (e.g., unsecured load) or propagate throughout the system (e.g., inattentive driver). One of the primary factors in BrTS is aging, “functionally obsolete” infrastructure that fails to satisfy current design standards and the increase in fleet size, weight, and height. The American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) 2017 Infrastructure Report Card shows that among 614,387 bridges in the United States, 9.1% were structurally deficient and more than 1 in 8 (13.6%) were functionally obsolete (ASCE 2017). As early as 1973, Hilton (1973)

investigated crashes involving highway bridges in Virginia and listed “inadequate vertical clearance” as one of the key contributing factors. In the 1980s, Shanafelt and Horn (1980, 1984) authored two NCHRP reports on damage evaluation and repair methods for prestressed concrete bridges and steel bridges, respectively. In the 1990s, some state DOTs started to develop procedures and methods to quantify the vulnerability of bridges to collision damage, including the Collision Vulnerability Assessment of the New York State DOT (NYSDOT 1995). Another major contributor to BrTS crashes is driver behavior and error. These include inattentiveness, failure to comply with truck routing regulations, insufficient understanding of low-bridge warning signs, load shifting in transport due to packing problems, inaccurate measurement of load height, and the use of passenger car GPS rather than commercial GPS units that offer information on roadway restrictions (FMCSA, n.d.). Confounding factors include the lack of alternative routes at low bridges, lack of route planning by haulers, and inadequate or outdated signing at and on the approach to low bridges (Agrawal, Xu, and Chen 2011).

Challenges in implementing mitigation strategies and enforcing policies: The state of the practice for mitigating a BrTS includes a multitude of engineering, operational, education, outreach, and enforcement initiatives. Engineering strategies, such as modifying bridge and tunnel dimensions, can be highly effective but are very costly and are not immediately feasible on a systemwide scale. Other engineering measures, such as signing and active warning devices, can be more economical but may not be as effective, particularly if the messaging is unnoticed or unclear to the truck drivers or too close to the structure to act. Passive signing is estimated to be 10% to 20% effective, and active warning systems are estimated to be 50% to 80% effective (Nguyen and Brilakis 2016). There are also several mitigation strategies to address the operation and routing of oversize loads, including policies and procedures related to the vehicle permitting process, oversize-vehicle routing systems, carrier equipment, pilot car/escort vehicle guidance, and technology. Challenges related to these operational strategies include noncompliance or improper use of existing procedures and guidance. Human-factor-specific practices, like training and education, or the use of predeparture checklists also address common root causes of BrTS crashes. While there are numerous options available to mitigate BrTS risk, any individual strategy is associated with strengths and limitations. A more reliable solution for reducing BrTS risk will rely on a variety of countermeasures, some relatively inexpensive and quickly implemented, others requiring substantial investment, planning, and an ongoing effort to operate and maintain. A combination of countermeasures can also provide redundancy and help to address the multitude of critical events that can lead to a crash.

1.4 Purpose of the Guide

The purpose of this guide is to assist transportation agencies, commercial motor vehicle safety agencies, motor carriers, and practitioners in preventing and mitigating BrTS risk. This guide will help agencies and analysts overcome the challenges in mitigating BrTS risk by providing methods and information in five areas:

- Identify high-priority locations: This includes methods for locating crashes to specific bridges and tunnels as well as methods (both crash-based and risk-based) for prioritizing bridges and tunnels. The risk-based approach helps agencies to proactively assess the vulnerability of the infrastructure against collision impact.

- Diagnose risk and crash contributing factors: This includes a list of common infrastructure, operational, and other factors that increase BrTS risk. This also includes methods to analyze and identify risk and crash contributing factors.

- Select countermeasures to mitigate BrTS risk: This includes information on the applicability, effectiveness, cost, and consideration of various engineering, operational, education, and

- Evaluate the effectiveness of investments: This includes fundamental concepts for tracking and evaluating projects and programs, including measures of effectiveness, methods, and data needs. This will allow agencies to better understand the return on investment and help inform future funding and policy decisions.

- Enhance BrTS data and analysis capabilities: This includes opportunities to contribute data to a national BrTS Clearinghouse to improve the completeness, accuracy, and accessibility of a comprehensive and up-to-date inventory of BrTS data. These BrTS data can be used by practitioners to identify and address priority issues or by researchers to advance the state of the practice.

enforcement policies and strategies. This provides a data-driven, decision-support system to inform the selection and prioritization of safety solutions. This also supports the development of agencywide strategies and procedures to mitigate BrTS risk.

1.5 Target Audience

The target audience includes commercial motor vehicle permitting officials, transportation planners, traffic engineers, bridge and tunnel engineers, maintenance personnel, law enforcement officers, drivers, motor carriers, and industry organizations. While this is a diverse audience, there are many shared concerns with respect to BrTS risk. For instance, transportation agencies, industry organizations, and motor carriers likely share an interest in policy and operational measures as well as educational and outreach measures. All stakeholders are likely interested in crash contributing factors and factors that increase BrTS risk. In terms of countermeasures, transportation planners, bridge engineers, and traffic engineers may be more interested in infrastructure improvements, while law enforcement officers are likely more interested in behavioral measures. This guide includes information across all these areas to reach a diverse audience and address the array of BrTS contributing factors. The guide does not explicitly address incident response, which is critical to addressing the aftermath of BrTS, but it is not directly related to mitigating BrTS risk. Readers can refer to the following resources for further information on post-incident response:

- Case Study: Response to Bridge Impacts – An Overview of State Practices (Dunne and Thorkildsen 2020).

- Post-crash Emergency Response Toolkit (European Bank for Reconstruction and Development 2021).

- “Incident Management” (DHS, n.d.).

- National Incident Management System: Intelligence/Investigations Function Guidance and Field Operations Guide (DHS 2013).

1.6 Organization of the Guide

The remainder of this guide follows the general systemic approach to safety management, providing a framework for assessing risk (Chapter 2), identifying countermeasures (Chapter 3), selecting and prioritizing countermeasures (Chapter 4), and evaluating completed projects and programs (Chapter 5).

Chapter 2 focuses on BrTS risk assessment, beginning with an overview of risk-based assessments and common risk factors. It then describes data collection and analysis procedures that agencies could use to identify jurisdiction-specific risk factors and assess BrTS risk using state, regional, or local data. The chapter concludes with data collection and analysis procedures for updating a national BrTS Clearinghouse. Agencies can use the framework in this chapter to estimate the risk (i.e., likelihood and consequences) of a BrTS crash based on bridge, tunnel,

roadway, and operational characteristics. This will help agencies prioritize locations for further investigation and potential treatment or to prioritize proposed projects within a larger program. Transportation agencies might use this information to identify roadway, bridge, and tunnel locations for potential infrastructure improvement projects. Commercial motor vehicle enforcement officials might use this chapter to identify risk factors and potential locations for implementing enforcement strategies. Motor carriers might use this chapter to identify routes that are higher risk and instruct their drivers to avoid such routes.

Chapter 3 focuses on countermeasure identification, beginning with a discussion of general considerations and a summary of common BrTS risk factors with applicable countermeasures. The remainder of the chapter provides detailed descriptions of individual countermeasures, including cost, effectiveness, service life, and other considerations. Once an agency identifies factors that contribute to BrTS, the next step is to identify appropriate countermeasures to target the underlying issue(s). If a transportation agency prioritizes a specific bridge that is at high risk of being struck and identifies the specific risk factors, then the agency might use this chapter to identify appropriate infrastructure or operational countermeasures to mitigate BrTS risk. Motor carriers might use this chapter to identify opportunities for policy, education, and technology strategies that could help reduce their risk of BrTS, which could lead to long-term benefits such as reduced costs (e.g., insurance, direct repairs) and reduced employee issues (e.g., pain and suffering).

Chapter 4 describes quantitative and qualitative measures for selecting and prioritizing countermeasures, focusing on an analysis of alternatives. While countermeasure selection starts with a larger list of options, this chapter will help agencies pare down the initial list to the preferred alternative through a more detailed analysis of the alternatives. This applies to infrastructure, operation, education, enforcement, and policy strategies.

Chapter 5 focuses on three levels of post-implementation evaluations: project, countermeasure, and program level. It describes project tracking and the fundamental concepts for evaluating projects, countermeasures, and programs, including measures of effectiveness, methods, and data to track before, during, and after implementation. Agencies can use this chapter to determine the effectiveness of a particular project, group of projects, or policy. Agencies might use the evaluation results to inform future funding and policy decisions. For instance, if evaluations show that certain educational or enforcement programs are consistently effective, then law enforcement agencies and motor carriers may choose to continue or expand those programs. If evaluations show that specific infrastructure or operational strategies are effective at reducing site-specific or systemwide risk, then transportation agencies may choose to implement similar strategies at additional locations or incorporate them as standards for future projects. On the other hand, if an evaluation shows that a project or program is not meeting expectations, then an agency may address the situation accordingly (e.g., install supplemental measures, discontinue or revamp the program).