Summary

STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM

Recommended intake levels for nutrients and other dietary components were designed initially to prevent nutrient deficiency diseases in a given population, and the original methodological approach used to derive intake values did not include consideration for other applications. However, with the increasing globalization of information and the identification of a variety of factors specific to different population subgroups (e.g., young children1 and women of reproductive age) that influence their nutritional needs, there has been increasing recognition of the need to consider methodological approaches to deriving nutrient reference values (NRVs) that are applicable across countries and that take into account the varying needs of different population subgroups.

In response to the recognized need for a more comprehensive approach to developing nutrient intake recommendations, the United Kingdom, the European Union, and the United States jointly with Canada developed dietary reference values (DRVs) and Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) for their respective populations. Other authoritative bodies around the globe developed similar approaches, including in China; Korea and Southeast Asia; Germany, Austria, and Switzerland; Australia and New Zealand; and Mexico. This set the stage for discussions about harmonizing the different methodologies being used to establish NRVs.

One outcome of these discussions was the convening of a group of

___________________

1 In this report, “young children” includes birth up to 5 years of age.

international experts in Italy, in 2005, to review the methodological approaches in use at that time. Attendees at the Italy meeting identified four basic reasons why global harmonization of the methodologies is important. A harmonization of the process will:

- Improve the objectivity and transparency of values derived by diverse national, regional, and international groups.

- Provide a common basis or background for groups of experts to consider throughout processes leading to NRVs.

- Permit developing countries, which often have limited access to scientific and economic resources, to convene groups of experts to identify how to modify existing reference values to meet their populations’ specific requirements, objectives, and national policies.

- Supply a common basis for the use of reference values across countries, regions, and the globe for establishing public and clinical health objectives and food and nutrition policies, such as fortification programs, and for addressing regulatory and trade issues.

Here, the committee defines the harmonization of approaches as reaching global agreement on the most appropriate methods or procedures for deriving NRVs. The concept of methodological harmonization is particularly important for low- and middle-income countries whose access to essential resources is limited or absent.

THE COMMITTEE’S TASK

The need for guidance and recommendations about methodological approaches, as well as their potential for application to an international process for the development of NRVs, and particularly for young children and women of reproductive age, prompted the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to ask the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to hold a workshop, convene a consensus committee to examine these issues, and make recommendations for a unified approach to developing NRVs that would be acceptable globally.

To set the stage for the consensus committee’s work, a workshop, Global Harmonization of Methodological Approaches to Nutrient Intake Recommendations, was convened at the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) headquarters in Rome. The workshop provided a venue for dialogue and discussion about the experiences, both positive and negative, of current approaches to deriving NRVs (see Appendix B for the workshop agenda), and it served as a foundation for discussion of evidence by the consensus committee in carrying out its task.

The Gates Foundation asked the committee to consider the implications of harmonizing methodological approaches to deriving NRVs for a specific population subset—young children (birth up to 5 years of age) and women of reproductive age. The committee was not asked, however, to address the derivation of any actual values for NRVs. Nor was the committee asked to determine how to implement its recommendations for a harmonized approach to deriving NRVs, although it did consider possible next steps toward implementation (see Chapter 5). The committee’s task is shown in Box S-1.

KEY FINDINGS, CONCLUSIONS, AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The purpose of developing NRVs is to assure that, if met, the majority of a generally healthy population will have sufficient intake levels to prevent nutrient deficiency disease and avoid adverse effects of excessive intake. When applicable, reference values may also be determined to reduce risk of chronic disease.

The traditional risk assessment model for deriving NRVs led to the development of a range of reference values. These include the average nutrient requirement (AR), the recommended intake (RI)2 (derived from the average requirement), and the safe upper intake level (UL). The AR and the UL are core reference values. To reach global agreement on the most appropriate

___________________

2 Other terms include reference nutrient intake (RNI), recommended nutrient intake (RNI), recommended dietary allowance (RDA), and recommended dietary intake (RDI).

methods and procedures for the derivation of standards used to establish NRVs, the focus must be on these two values.

Recommendation 1. Nutrient reference expert panels should make two values their priority: specifically, the population average requirement (AR) and safe upper levels of intake (ULs). Their reports should estimate the interindividual variability of requirements and use it to derive the AR. The expert panel should also acknowledge the basis and uncertainty in estimation of both values.

The committee came to the following conclusions:

The need for nutritional benchmarks is critical all over the world. This shared need, combined with the substantial effort and expense of deriving NRVs, is a strong justification for international cooperation. Indeed, convening a global expert panel would be ideal for promoting a harmonized process and making efficient use of the funding to support these efforts. The committee deliberated on the potential role of a central organizing body, such as the World Health Organization (WHO) or FAO. WHO and FAO are both international organizations responsible for facilitating cooperation in global health, nutrition, and agriculture. Setting and promoting international norms and standards is one of WHO’s responsibilities. FAO, similarly, is responsible for supporting international policies that make up-to-date nutrition information available.

Given the interface between their missions, WHO and FAO have a history of collaboration, they share funding for the Codex Alimentarius, and have over time established a trust fund to support the capacity of participants in low- and middle-income countries to participate in the nutrient reference setting process. Alternatively, it is possible that a technical organization, such as the International Union of Nutritional Sciences (IUNS), might have equally good convening authority among scientific experts needed for an international harmonization effort. Another possibility is that international collaboration could be carried out at the regional level.

Recommendation 2. To set a nutrient reference value, ideally, a global body, such as the World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), or the International Union of Nutritional Sciences (IUNS), or secondarily, a regional consortium, should convene an expert panel to identify relevant outcome measures and request a systematic review for the nutrient of interest,

and appoint a panel to advise on how to adapt the values to different population subgroups and settings.

Regardless of the convening organization, there are certain key steps in the process of deriving NRVs that should be consistent across countries. Inherent in the decision-making process is the determination of whether an existing NRV can be accepted, updated, or a new value should be derived. Either way, selecting a methodological approach for a nutrient review depends on the role of the nutrient in meeting physiological needs, intake patterns, bioavailability of the nutrient, and the presence of infection and other local factors that influence the requirement for the population under consideration. The option to accept, update, or adapt existing NRVs means that it is not necessary to go into a full review; rather, adjust existing reference values and document how it was done. For new values, a full review is required.

Recommendation 3. Expert groups should assess relevant evidence and, as needed, analyze existing or new data to assess the characteristics of various diets that can affect the bioavailability of specific nutrients.

Recommendation 4. When deriving nutrient reference values, countries or regions should look at existing values derived by expert panels and determine whether to accept, update, or adapt them to their context, if possible. If values are not relevant locally, an expert panel should adapt values to the local context or modify existing values from other experts.

A thorough understanding of the uncertainties that affect the review process is essential to maintaining the credibility of the nutrient review process, as well as the accuracy and relevance of NRVs; enabling decision makers to use NRVs in nutrition policy; and developing quantitative evidence assessment models.

Recommendation 5. After having adapted or created new nutrient reference values (NRVs), to achieve transparency the nutrient review expert panel should clearly report the reference population, adjustment factors, and the methodology used. Expert panels should also document the uncertainty in the evidence and in the methods used to develop the NRVs quantitatively. If this is not possible, then they should provide a qualitative evaluation of the confidence in the body of evidence and in the methods used.

* Risk assessment is a process of (1) identification of risk of toxicity, (2) dose–response assessment, (3) assessment of the prevalence of intakes outside the reference values, and (4) characterization of risks association with excess intake.

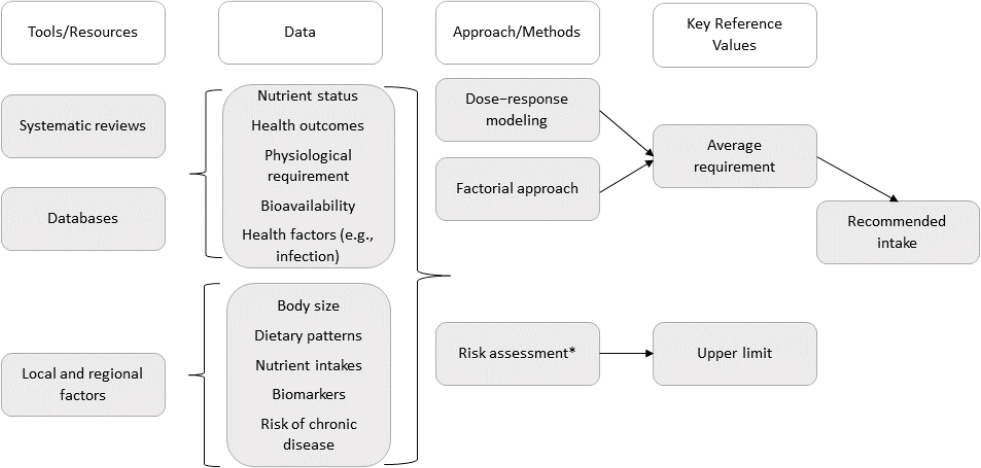

Since the first NRVs were developed, the process for deriving them has been made more scientifically rigorous and transparent through the use of new tools that were either unavailable or not used in the past. These include systematic reviews, larger and more accessible databases, information of factors affecting culture- and context-specific food choices and dietary patterns, new modeling techniques (e.g., new tools for assessing risk of bias), and new metabolic markers of nutritional status. Based on its assessment of the strengths and weaknesses in methods currently being used to derive NRVs, as well as the rigor and transparency made possible by the use of these tools, the committee developed a framework for harmonizing the process of deriving NRVs (see Figure S-1). The framework provides a platform for establishing NRVs that can be applied across countries and various population subgroups. The framework involves four major steps: (1) choose the appropriate tools, (2) collect relevant data from these tools, (3) identify the best approach, or method of derivation, for the nutrient under consideration, and (4) derive the two key reference values, the AR and UL.

ASSESSMENT OF EXEMPLAR NUTRIENTS

The committee applied the framework to two population groups, young children and women of reproductive age, and used case analyses of three exemplar nutrients—zinc, iron, and folate—to examine the feasibility of its recommendations for harmonizing the methodological approaches to

deriving NRVs on a global scale. The committee did not actually derive any NRVs. Rather, its focus was on the derivation process and mostly on which of the two recommended approaches to deriving an AR, dose–response modeling or the factorial approach, could apply to these three nutrients. Also, the committee did not carry out analyses for both population groups for all three nutrients; rather, the case studies were selected to illustrate the methodological applications across age groups.

Zinc Case Analysis

Certain population groups, especially those living in low- and middle-income countries, are known to be potentially deficient and particularly vulnerable to the constellation of problems that present with zinc deficiency. A number of factors contribute to the risk of zinc deficiency in populations, including poor dietary quality. In other instances, while diets may not necessarily be low in zinc, bioavailability caused by dietary factors such as high phytate concentration in foods may be important. Other causes of zinc deficiency include an increase in the zinc physiological requirement to meet the needs for pregnancy and growth in young children and an increased zinc loss caused by diarrheal infections. From its review of evidence, the committee made the following findings:

- A sensitive, specific biomarker of zinc nutrition is not available.

- Although severe dietary zinc restriction (i.e., diets providing less than 1 mg zinc per day) causes a marked, rapid decline in plasma zinc, it can take weeks for levels to return to baseline upon zinc repletion. Surveys show that plasma zinc concentrations remain relatively stable over a wide range of less restricted zinc intakes. In contrast, supplements have been shown to cause prompt increases in plasma zinc concentrations irrespective of dietary intake. Although linear growth has been recommended as a functional indicator of zinc status, because low height- or length-for-age has been shown to be responsive to supplemental zinc, as with plasma zinc concentrations, the response to additional dietary zinc is not as strong as the response to similar doses of supplemental zinc.

- Among adults, dietary phytate is a major determinant of zinc absorption. Thus, the phytate:zinc molar ratio is often used to calculate a population’s dietary zinc requirements. However, a recent study failed to find an effect of phytate on zinc absorption in young children and in pregnant or lactating women. Additional data are needed to determine if age or physiological zinc requirements influence the effect of phytate on zinc absorption. Because zinc is generally associated with proteins in body cells and tissues,

-

it is important to determine whether dietary zinc recommendations need to be matched to the amount and type of protein in the diet (i.e., animal or vegetable). When developing zinc supplementation or fortification programs, it is generally assumed that all zinc organic and inorganic salts are equally absorbed. However, the bioavailability of zinc–amino acid complexes may be used more effectively if certain amino acids are functioning as ligands.

- Survey data suggest that growing children are particularly vulnerable to developing zinc deficiency and are more prone to develop gastrointestinal or pulmonary zinc infection as a result. The physiology underlying this increased vulnerability in children is unknown. Possibly, children lack tissue or cellular reserves to draw on when diet is marginal. Alternatively, their immune systems are less well developed than adults. Research is needed to determine if a modest, consistent increase in dietary zinc could reduce a child’s susceptibility to zinc deficiency by increasing the level of zinc reserves or enhancing immune function.

- Because the physiological requirements and ARs for young children and women of reproductive age that have been made by the authoritative bodies reviewed in this report are very similar, efforts should be made to consolidate these estimates globally. However, there may still be a need to set national RIs based on the dietary zinc source (i.e., bioavailability) and the average body size of the population.

Proposed Solutions

Because a sensitive biomarker of zinc inadequacy is not available, the factorial method is the only feasible approach for estimating dietary zinc requirements at this time. The factorial approach involves estimating the amount of a nutrient needed to replace that lost through fecal, urine, and skin routes, either unchanged, or as a metabolite, then estimating the additional amount required to support growth, pregnancy, or lactation. Currently, all international and national groups reviewed in this report use the factorial approach for establishing zinc nutrient intake recommendations. However, quantitative data are lacking for growing children. In addition to data gaps identified and listed in the findings, including the need to continue to search for a reliable biomarker of zinc status that is more sensitive to changes in dietary zinc than plasma/serum zinc concentrations, studies are needed to help identify the potential influence of genetic polymorphisms (i.e., genetic variations) on individual dietary zinc requirements. Furthermore, the development of comprehensive models of inhibitors of

zinc absorption across diverse populations would improve estimates of dietary requirements.

Iron Case Analysis

Iron deficiency is a common nutritional deficiency worldwide and a major cause of infant mortality. Young children and women of reproductive age, especially during pregnancy, are at increased risk because of the high iron requirements for growth or the replacement of iron lost in menses. Iron deficiency is particularly common in low-income countries because of limited intakes of animal products (which contain the more highly bioavailable heme iron) and the regular consumption of cereal grain and legume-based diets (which are low in bioavailable iron owing to the presence of phytate and other compounds that inhibit iron absorption). Iron requirements can also be affected by the effects of infection and inflammation on the hormone hepcidin, a key regulator of iron. From its review of evidence relevant to iron NRVs, the committee made the following findings:

- The derivation of most values used for bioavailability is neither transparent nor evidence based. This is because data on iron bioavailability from the whole diet is limited. The one exception is the approach used by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), which is based on a model in which the iron absorption from the whole (Western) diet is predicted using good quality individual data on dietary intake, serum ferritin concentration, and calculated physiological iron requirements. The model has since been refined and updated and an interactive modeling tool published.

- The lack of agreement for reference values is attributable largely to the choice of bioavailability factor used to convert physiological requirements into dietary intakes, which results from limited information on iron absorption from complete diets, as well as assumptions about iron storage at conception.

- When assessing the iron status of a population in relation to public health policies such as food fortification, it is crucial to have good quality representative data for iron intake. If the mean iron intake is below the AR, then evidence of iron deficiency must be supported by measures of iron status. However, because dietary iron exists in two forms, measuring dietary intake is difficult owing to limited information on heme iron in food composition databases. In addition, several biomarkers of iron status (e.g., ferritin) are modified by infection, chronic disease, and deficiencies of other nutrients.

- Pregnancy is a normal physiologic condition, which should not require a major change in food intake, provided the habitual diet

-

contains all nutrients at levels that are consistent for optimal health. However, many women become increasingly iron deficient or anemic during pregnancy because they do not have adequate iron stores at conception or dietary iron bioavailability is insufficient to meet their needs, despite the well-known adaptive mechanisms that are designed to maintain iron homeostasis.

- NRVs are derived for healthy populations, and although physiological requirements for iron should be the same for each population subgroup in every country or region, dietary iron bioavailability will depend on the local diet composition, the risk of anemia in the population, and infection or inflammation, which may change the AR.

- There are several factors related to diet, lifestyle, infection, and disease that confound the association between iron intake and health outcomes, obscuring the dose–response relationship needed to accurately estimate reference values.

- There are challenges to setting an iron UL, but such a value is essential for evaluating the safety of food iron fortification and other public health programs.

Proposed Solutions

Although the factorial method has been universally adopted by authoritative bodies globally, there remains wide variation in NRVs determined for women of reproductive age, mainly because of different calculations used to transform physiological requirements into dietary intakes. Although the bioavailability model used by EFSA is the preferred approach to determine iron bioavailability from the whole diet, it is applicable in low- and middle-income countries only if it is appropriately adapted. In low- and middle-income countries, intakes of iron absorption inhibitors may be higher and heme iron intakes lower than in Western diets. Additionally, many low- and middle-income countries have high burdens of infection and other widespread health concerns, including hemoglobinopathies and thalassemia, which affect iron metabolism and biomarkers of iron status. Thus, there is also a need to take into consideration the effect of infection and inflammation on serum ferritin concentration, which is one of the most widely used biomarkers of iron status. Serum ferritin is also an important tool for identifying poor iron status among populations in low- and middle-income countries.

Folate Case Analysis

The global prevalence of folate deficiency and depletion is not well documented. However, populations in low- and middle-income countries are not necessarily at greater risk of deficiency than those in high-income countries, especially if the usual diet is high in legumes and green leafy vegetables. Inadequate intakes are less prevalent in populations where folic acid has been added to staple foods as a result of widespread fortification policies. From its review of evidence, the committee derived the following findings:

- Measurement of food folate levels for use in the derivation of NRVs may require adjustment. For example, validation of folate values in food composition tables is an area of concern. In the 1980s and 1990s it was recognized that folate content in foods can be substantially underestimated unless the tri-enzyme procedure for releasing the vitamin from food is used. This likelihood of underestimation can explain discrepancies between intakes calculated from older food composition data versus more recent estimates based on measures of folate status.

- Some food preparation procedures can cause substantial losses of folate, which is relatively unstable to heat and oxidation. From 50 to 80 percent of the folate in green vegetables, and 50 percent of the folate in legumes, is lost during boiling. When estimating the prevalence of inadequate intakes, folate values based on local cooked recipes should be used whenever possible. While cooking techniques affect the amount of folate required from food sources, it does not affect physiological requirements.

- As with food preparation, while folic acid fortification of staple and other foods does not affect the physiological requirement for folate, it does affect the amount required from food sources. Therefore, data on folate intake in food intake surveys must include the amounts of fortified food consumed and the levels of folic acid in that food. High folate status has emerged in a number of populations after initiating folic acid fortification programs. Although folic acid is generally regarded as not toxic, it may be a factor in neurological injury when pernicious anemia is present. Thus, avoiding excessive intakes and monitoring folate status may be especially important in populations with a high prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency since there is some evidence that a high folic acid intake may exacerbate B12 deficiency.

- It is unlikely that local adjustments will need to be made in requirements that depend on breast milk folate concentration. Folate

-

requirements are not affected by maternal status or intake of foods with different bioavailabilities (except for the higher bioavailability of folic acid in fortified foods). Thus, adjustments are probably not necessary.

- The prevalence of the MTHFR genotype varies substantially across populations. In Caucasians, this genotype occurs in from 2 to 16 percent of the population, compared to 25 percent of Hispanics, and a very low percent of Africans. There appears to be large variability in prevalence across Asian populations. Compared to CC or CT genotypes, homozygosity for the T allele results in lower plasma and erythrocyte folate, and higher plasma homocysteine in those with plasma folate below about 15 nmol/L. Because deriving an RI to cover 97.5 percent of the population depends on the variation around the AR and because populations with a higher variance will have a higher RI, a high prevalence in a population may justify a higher coefficient of variation for deriving an RI, as was done in recommendations from the Germany, Austria, and Switzerland group.

- Folate is synthesized by malarial parasites, so assessment of red blood cell count folate should not be conducted immediately after an episode of malaria with fever, to avoid spuriously high values.

- There is no evidence that deficiencies or high intakes of other micronutrients affect folate requirements.

Proposed Solutions

Generally, dose–response modeling is used when there is a clear relationship between the intake of a nutrient and a metabolic or functional outcome, such as preventing deficiency disease, assessing biomarkers for health or risk of disease, or determining a safe upper level of intake. The dose–response method is the preferred approach to derive ARs for folate.

Folate recommendations for women and children are remarkably similar across countries, owing to general agreement on biomarker cut points and the relatively few factors that can affect requirements. There are no major deterrents to using existing reference values published by authoritative bodies or to modifying them to the local context. However, the committee identified a number of data gaps for deriving new, country-specific folate NRVs:

- The lack of validated data on the folate content of foods in low- and middle-income countries, especially cooked foods;

- Increasing, but still insufficient evidence for population prevalence of polymorphisms and their effect on folate requirements;

- Knowledge gaps around the local contribution of other micronutrient deficiencies (vitamins B12, riboflavin, and B6) to plasma homocysteine levels; and

- The need to consider local consequences of poor B12 status on the prevalence of neural tube defects and its interaction with high folate intake.

CONCLUSION AND NEXT STEPS

From its assessment of the current process for deriving NRVs, the application of new tools to this process, and its three nutrient case analyses, the committee concluded that it is feasible to harmonize the process to derive reference values globally.

Recommendation 6. Researchers and funding organizations should advance the knowledge of nutrient requirement research by supporting research that uses modern technology, techniques, or methods for assessing requirements.

In addition to the four major steps of the framework illustrated in Figure S-1, the committee identified six core values as being critical to this effort:

- NRVs are regularly updated.

- The process is clear and transparent.

- The methods are rigorous and relevant.

- Factors influencing the NRV are documented.

- The strength of the evidence is determined.

- The review is complete and efficient.

The many potential users of NRVs include international organizations such as WHO and FAO; nonprofit organizations; local, regional, and national governments; academic researchers; health care providers; the food industry; and the general public. Because of the many ways that NRVs are used and applied, from formulating food and nutrition policies to planning and assessing diets for individuals and groups, it is important that users of NRVs understand their derivation, particularly the AR and UL, as well as their application to public health.

Among the issues raised at the Global Harmonization workshop was that stakeholders need to be convinced that a harmonized approach to setting NRVs is advantageous and necessary. Influential organizations such as WHO and FAO, policy makers, nonprofit organizations, and researchers are needed to help launch an initiative that will explain the proposed har-

monization approach and advocate for its implementation, including its advantages as well as the reasons for using a shared paradigm.

While this report describes the data gaps and offers a model for harmonizing the approach to deriving NRVs globally, future dialogue will be needed across countries to garner support for a harmonizing effort and to identify a pathway for implementing the recommendations of this report. This means that it is crucial to have active participation and buy-in from the organizations and groups to whom global harmonization will be entrusted. The collective effort of these groups is needed to launch an initiative that will explain the proposed harmonization approach and advocate for its implementation, including its advantages and the reasons for a shared paradigm. An important next step is for the key enablers of harmonizing NRVs to develop a tool kit that participants, particularly those from low- and middle-income countries, can use to guide the development of methodological approaches to deriving NRVs for their populations. This report’s intent is to provide the guidance needed as global stakeholders consider moving toward the subsequent steps of implementation, dissemination, and evaluation.