Life-Cycle Decisions for Biomedical Data: The Challenge of Forecasting Costs (2020)

Chapter: Summary

Summary

Biomedical research results in the collection and storage of increasingly large and complex data sets. Preserving those data so that they are discoverable, accessible, and interpretable accelerates scientific discovery and improves health outcomes but requires that researchers, data curators, and data archivists consider the long-term disposition of data and the costs of preserving, archiving, and promoting access to them. All involved in data management throughout the data life cycle need to consider how data-related choices affect the costs of future preservation, management, and use. All need to be informed about the costs of retaining versus replacing data, the value of retained data, the costs of data curation and storage, and potential costs borne by future data users. These are integral to data preservation, archiving, and access promotion. Attention to and quantitative estimates of such costs will facilitate better allocation of resources and planning by those charged with guiding and investing in the production of scientific knowledge such as researchers, research-performing institutions, and funders.

The mission of the National Library of Medicine (NLM) within the National Institutes of Health (NIH) is to acquire, organize, and disseminate health-related information. At the request of NLM, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine convened a committee to examine and assess approaches and considerations for forecasting costs for preserving, archiving, and promoting access to biomedical research data. This report provides a comprehensive conceptual framework for cost-effective decision making that encourages data accessibility and reuse for researchers, data managers, data archivists, data scientists, and institutions that support platforms that enable biomedical research data preservation, discoverability, and use. The framework can be adapted by anyone responsible for managing data at any point in the data life cycle, but the analysis conducted during its application by researchers, data, data repository hosts, and funding institutions will vary greatly. Its purpose is to make the forecaster think of all the elements that could affect life-cycle costs so that costs can be understood and total costs be more accurately calculated. Other than the forecasting framework itself, the report does not include recommendations. Rather it describes the kind of environment conducive to forecasting the cost of sustainable data management, and provides strategies that could be applied by different members of the biomedical research community for creating those environments.

THE STUDY CHARGE

As part of its charge to develop and demonstrate a framework for forecasting long-term costs for preserving, archiving, and accessing various types of biomedical research data, the study committee evaluated economic

factors to be considered when examining the life-cycle costs for data acquisition, curation, and preservation; the cost consequences for various practices related to accessioning and deaccessioning data sets; economic factors if data are designated as high value; anticipated technological disruptors and future developments in data science in a 5- to 10-year horizon; and critical factors for successful adoption of data-forecasting approaches by research and program management staff. Per the statement of task provided to the committee by NLM, the framework was applied to two case studies in different biomedical contexts relevant to NLM data resources. The committee also organized a 2-day workshop to gather input on tools and practices that NLM could use to help researchers and funders better integrate risk-management practices and considerations into data preservation, archiving, and accessing decisions; methods to encourage NIH-funded researchers to consider, update, and track lifetime data costs; and burdens on the academic researchers and industry staff to implement these tools. A summary of workshop proceedings was published in a separate document (NASEM, 2020).

THE COST-FORECASTING FRAMEWORK

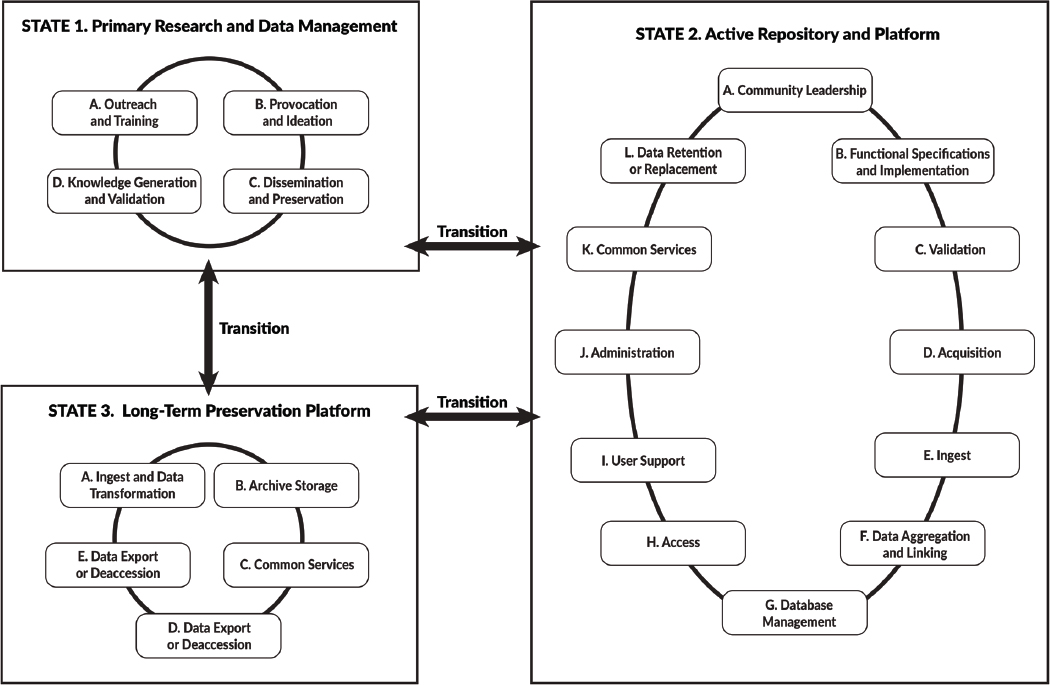

The framework for forecasting costs presented in this report first describes the different data environments in which data may be placed (herein referred to as “data states”; Box 2.1) and the various activities associated with those data states (Tables 2.1-2.3), and steps in the framework process are identified (Table 4.1). The cost drivers that may be important for each of those activities (Table 4.2) and questions that lead critical decision points related to those cost drivers are described in Chapter 4 through a series of questions to be answered by the forecaster. The committee tabulated those questions in a template that can be modified and used to inform a cost analysis (Appendix E). The forecasting framework does not offer computational models for quantifying costs because those applying the framework will have diverse interests in the framework’s application and diverse resources. Instead, it provides a comprehensive conceptual framework which the forecaster can use to identify what costs need to be quantified.

States of the Data Life Cycle

The data life cycle begins when data are collected during primary research and continues through data analysis, preservation and curation, reuse, storage, and potentially to deaccession. The data life cycle is not necessarily linear—data may be reused and repurposed, combined with other data, and analyzed in a variety of ways and for different purposes throughout their existence. How actively data are used during the data life cycle may change: they may be used often when initially collected and then only periodically after placed in a repository. At some point, they may become dormant and be placed in an archive for long-term preservation. They may be rediscovered at any time and again be actively used. Ideally, the data states in which the data are placed throughout their existence allow for different types of activities. Data may be moved from one data state to another as needs arise, the data may transition in a nonlinear manner, or some data may not ever transition into all the data states.

Digital data may transition among three states in the data life cycle:

- State 1: The primary research and data management environment where data are captured and analyzed. It is possible that no one managing or using a given State 1 data environment is focused on standardizing, documenting, sharing, or preserving data and algorithms.

- State 2: An active repository and platform where data may be acquired, curated, aggregated, accessed, and analyzed. Such a repository is an active information system that usually provides services to a wide range of users. Where data are complex, confidential, or very large, it may be a platform for controlling access. Support may be provided for analyzing and processing data.

- State 3: A long-term preservation platform in which content is preserved across changes in governance, assessment of data value, and technology. The platform may include an extract of data from a single data set, multiple data sets, or an information system in a system-agnostic format. In this state, data are neither directly analyzable nor easily accessible.

These data states were conceptualized by the committee to communicate the characteristics of different environments, with different purposes, and having different data storage and preservation costs. The data states can be represented by Figure S.1, which also illustrates the major activities associated with each state. Tables 2.1-2.3 in the main body of the report provide more detail about the activities shown in the figure, as well as various subactivities that may occur and the personnel required to conduct them.

The Cost-Forecasting Process

Every data resource and management situation has unique characteristics and considerations, but there are commonalities in the cost-forecasting process. This report does not present an instrument for cost forecasting but rather a framework to help the cost forecaster build the instrument that is suitable for the particular application. The framework identifies many of the commonalities and should be considered a foundation for a detailed analysis that can be tailored for specific circumstances. Regardless of the application, the forecaster is encouraged to think about the entire life cycle of the data rather than of just the life of the data resource being developed or managed. It is more cost efficient in the long term if decisions are made in light of their impacts on future costs of management and data access. Table S.1 summarizes the steps necessary to understand the cost drivers that are important for

TABLE S.1 Steps for Forecasting Costs of a Biomedical Information Resource

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

a given information resource. The framework will assist the forecaster in identifying the characteristics of data and the biomedical information resource, the near-term and future data management needs, and the activities and decisions that are likely to be important drivers of near-term and future costs. The steps outlined in the table will not necessarily be performed in the order presented. Forecasting activities may occur concurrently, and they may need to be revisited as new information unfolds during analysis. The cost forecast can be quantified when decisions pertaining to them are made. Chapter 4 defines the primary cost drivers, listed below:

- Content (e.g., data size, complexity, and diversity; metadata requirements, depth versus breadth, processing level and fidelity; and replaceability of the data);

- Capabilities (e.g., user annotation, persistent identifiers, citation, search, data linking and merging, use tracking, and data analysis and visualization);

- Control (e.g., content, quality, access, and platform);

- External context (e.g., resource replication, external information dependencies, and distinctiveness);

- Data life cycle (e.g., anticipated growth, updates and versions, useful lifetime, and offline and deep storage);

- Contributors and users (e.g., contributor base, user base and usage scenarios, training and support requirements, and outreach);

- Availability (e.g., tolerance for outages, currency, response time, and local versus remote access);

- Confidentiality, ownership, and security (e.g., data privacy issues and licensing);

- Maintenance and operations (e.g., periodic integrity checking, data-transfer capacity, risk management, and system-reporting requirements); and

- Standards and regulatory compliance and other governance concerns.

Table 4.2 (in Chapter 4) illustrates which of these drivers are likely to be important for the major activities in the three data states. A series of questions related to each cost driver is provided in Chapter 4—and compiled in a template in Appendix E—to assist the forecaster in his analysis. The questions may need to be modified for a specific application of the cost framework: not all the guiding questions may be relevant to a given application, and not all relevant questions may be included. Through work with experts from within the institution that will host the data resource (e.g., the researcher’s university), relative costs may be estimated for activities for the data life cycle, and shorter-term costs may be quantified. Working through the guiding questions will also help the forecaster identify uncertainties in forecasted costs.

In most cases in which data are shared, the costs of long-term data preservation are not borne by a single individual or institution. Responsibility may be transferred, for example, from a researcher to a data platform host or between platform hosts. Understanding where costs will be accrued, who pays those costs, and who has managerial responsibility for them will inform decision makers for all data states. The cost-forecasting framework guides the forecaster through identification of those who hold responsibility for those factors.

CREATING AN ENVIRONMENT CONDUCIVE TO COST FORECASTING OF SUSTAINABLE DATA MANAGEMENT

Approaches to building and managing data repositories differ across institutions and among researchers, but regardless of where biomedical information resources are hosted, costs associated with personnel are likely to dominate total life-cycle costs. Storage, computing, and networking services also contribute to total cost. The ability of individual researchers to forecast and manage those costs depends on how well they understand service-provider costs and prices—whether those services are rendered by the research institution or by commercial providers. The lack of visibility regarding the true costs of data storage and access in individual laboratories, institutions, and community resources often hampers reliable cost forecasting.

Costs associated with long-term preservation, archiving, and access to biomedical research data will likely rise as data sets increase in size and complexity. Being able to forecast those costs is critical to the success of sustainable data preservation and access. Successful cost forecasting and sustainable data management require that those making decisions about data have the necessary information and incentives to recognize the full costs

of data management borne by all parties throughout the data life cycle. This is true whether decision makers are researchers, data scientists, research institution officials, data resource managers, or program managers at funding agencies or federal agencies that host and manage data on behalf of the broader research community.

To foster the scientific environment necessary to conduct better long-term cost forecasts now and into the future, a series of strategies, actions, and advances is presented below. The reader will need to determine how best to apply the strategies based on her role in the scientific endeavor and on the data environments under consideration.

Strategies

Efficient long-term data management and effective cost forecasting are more likely if data resource managers, cost forecasters, and institutions that support them apply the following strategies:

- Create data environments that foster discoverability and interpretability through long-term planning and investment throughout the data life cycle. Data sharing is not equivalent to data reuse, and developing processes that allow efficient data preservation, archiving, and access to facilitate data reuse could benefit scientific discovery.

- Incorporate data management activities throughout the data life cycle to strengthen data curation and preservation. Up-front costs may be increased, but data value may also increase, and the overall cost of research may be reduced.

- Incorporate the expertise and resources needed to create and curate metadata throughout the data life cycle, and in the transition between data states into the cost forecast. Data discoverability and reusability depend on adherence to community-accepted data and metadata standards.

- Weigh the benefits, risks (e.g., data loss), and costs (both up-front and anticipated) of data storage and computation options before selecting among options. A service may look attractive from an immediate-financing perspective, but service-provider strategies deserve vetting and verification, including examination of exit or transition strategies and costs. Long-term costs need to be informed by a provider’s risk-management strategies.

Actions

Individuals within specific biomedical sectors may collaborate to increase the efficiency of data management efforts, but there is little guidance available from funding agencies and the institutions that support biomedical data resources on practices for long-term management and cost forecasting for the biomedical research community. The following actions, especially if taken by funding agencies and institutions that support data resources, could expand the capacity of data producers and managers to make sound management decisions and cost forecasts:

- Explicitly recognize the value of State 2 data resources (i.e., active repositories) to the enhanced curation, discoverability, and use of data. This recognition is absent among the funding entities, researchers, and institutions supporting research, most of which apply the more traditional data management approach of transitioning data directly from the primary research environment (i.e., State 1) to long-term archiving (i.e., State 3).

- Structure cost forecasts for State 2 resources around communities and research programs rather than individual research efforts. Because State 2 resources serve communities of researchers, it may not be appropriate to allocate the costs of managing data in a State 2 resource back to the individual data contributor.

- Support standardization efforts, including developing tools and methodologies to estimate the cost of standards development, encouraging the use of those tools and standards as part of the funding programs where appropriate, and explicitly supporting metadata preparation. Support could take the form of funding and the provision of tools. Issuing clarifying language about the use of federal funds for data preservation beyond the performance period of the project that collected them would also help assist in the development and promotion of the use of community standards and metadata preparation.

- Identify incentives, tools, and training for adopting good data management practices, including cost-forecasting practices, which facilitate sustainable long-term data preservation, curation, and access. Such activities would benefit the entire biomedical research community, including the institutions and funding entities that support research. To support these endeavors, funding entities need to better understand research-community needs, help the community to define desired outcomes, support training, develop realistic and actionable metrics for success, and provide near-term incentives for success.

- Understand the charges associated with storage and computation in a data resource, regardless of who “pays the bill,” when making decisions about data and workflows. Institutions supporting research might develop mechanisms to inform researchers of the actual costs paid for the services rendered to them and encourage them to limit those costs.

Advances for Practice

Data are of little use without services to support them. Institutions that support primary research (State 1), or the development and management of State 2 (active) or State 3 (long-term preservation) repositories, face challenges understanding and providing the resources necessary to build, maintain, or otherwise acquire access to the systems necessary for a sustainable data-preservation platform. There is often confusion regarding who bears ultimate ownership (i.e., intellectual rights) and responsibility for data and data policies at the institutional level. Successful long-term data stewardship cannot be an ad hoc endeavor but rather needs to be planned in advance. Methodologies to forecast life-cycle costs for preserving, archiving, and accessing biomedical data are immature, and few tools and resources are available for those to quantify long-term costs with confidence. Making people aware of and accountable for their costs—and helping them understand that their actions generate costs for someone—might help researchers reduce resource consumption with more efficient workflows, experiment design, and data tracking.

The following activities, likely to be enabled at an agency or research-institution level, could advance practices and drive future improvements in the ability to forecast costs:

- Recognize explicitly that scientific data constitute an asset and that data stewardship requires support. Biomedical research data and data resources are vital to the delivery of good science and, ultimately, to the public good. The universities and institutions that support or enable research and host data resources, in turn, benefit from the recognition of that support.

- Systematically collect data on costs associated with the biomedical research data enterprise to allow the translation of the framework outlined in this report into resources and methodologies that would benefit individual researchers and repository institutions. A clear locus of responsibility for compiling this information systematically is necessary.

- Develop easier mechanisms for creating and maintaining data management plans (DMPs), automatically incorporating data and metadata into resources, and improving citations for data to work together with other research products. By providing these mechanisms, funders and research institutions could help improve efficiency, return value for stakeholders, and increase the likelihood that stakeholders will make sound data-related decisions.

POTENTIAL DISRUPTORS

Disruptors are considered anything that may cause radical changes to the ways research is conducted and data are collected, used, archived, or preserved. Disruptors may be positive, negative, or mixed, and may either raise or lower the cost of data management and preservation. There is no way to fully anticipate potential disruptor impact, but remaining aware of it and building flexibility into data can help to mitigate the effects. There are numerous issues that could lead to disruptions, including issues such as the evolving open data practices and the application of “findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable” (FAIR) data principles for research data; developments in cybersecurity (both regulatory and legal requirements that may interact with privacy and human-subjects

regulations, and in terms of changing threat environments); major changes in funding levels and flows; more general changes in the vendor landscape (e.g., bankruptcies, mergers, and acquisitions); technology production and supply chains; and environmental or geopolitical developments. Many of these are discussed throughout this report. Chapter 7 of this report includes discussion of the following potential disruptors:

- Biomedical data volume and variety: Sudden orders-of-magnitude increases in data collection in domains such as imaging and multiscale high-performance computing simulations have moved biomedical research into the realm of “big data.” This has been observed, for example, given recent advances in genomics research. Biomedical research will experience growth that tends to add dimensions to the data space or to extend a dimension by an order of magnitude.

- Advances in machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI): The increased use of machine learning and AI techniques has accompanied the increases in data volumes. Automatic annotation of data and metadata generation using AI that allow regular updates to volumes of data increases the need for active storage approaches and requires programmatic access to data; this may also have implications for metadata requirements. Certain compliance and regulatory processes may be automated, but AI may also give rise to new challenges as it upends assumptions about data identifiability and data security.

- Changes in storage technologies and practices: While costs per byte stored per year continue to drop, although more slowly than in the past, the aggregate size of the data being stored and managed is growing quickly. Some sites face physical facilities constraints on the amount of storage they can support locally; the capital investment costs of purchasing and upgrading storage are also challenging. Cloud providers offer greater flexibility in terms of expansion, and costs of storage and compute services continue to become more attractive. On the other hand, if there is a need to change providers, moving large amounts of data is technically challenging and could involve a variety of costs of which the information resource manager must be aware. In other words, vendor lock-in could be a risk.

- Future computing technologies: The scale and speed of the adoption of emerging technologies in the next 5 to 10 years is uncertain. For example, the ability to move computation to data rather than data to computation can change practices and costs. New cloud cost models may be the determinant factor for the overall cost of data. Emerging edge computing models, reliance on non–von Neumann architectures, and specialized hardware such as machine learning accelerators may also reshape how data are stored and reused, and the associated costs of storage and usage.

- Workforce development challenges: It is difficult and expensive to attract and sustain the needed size and quality of workforce when industry offers higher wages than those offered in the public sector and academia.

- Legal and policy disruptors: Changes in legislation and policy related to issues such as data sharing; data identifiability; permissible data collection, storage, and sharing; and human-subjects research may require changes in the way data are stored, shared, and accessed.

ENSURING LONG-TERM STEWARDSHIP

It is not common practice to think beyond a current funding period when developing a data management budget, and the current system for funding research is not conducive to data life-cycle cost forecasting.

At present, cost forecasting is typically short term and is often conducted only at the onset of an endeavor when many issues are uncertain (e.g., data quantities, quality, and format). Planning horizons are dictated by funding streams (e.g., federal budget allocations, grant levels) and thus extend only for the life of the project, excluding post-project data-preservation issues. Many researchers think about the disposition of their data after their primary research is complete and strive to make those data public. DMPs (see Appendix B) today are typically static documents prepared as a mandatory—but not necessarily influential—part of the funding process. Placing more emphasis on quantified cost forecasts during the award process may be one way to incentivize early planning and communication, even if cost forecasts are uncertain. However, placing greater emphasis on cost forecasting at that time does not mean that the forecasts will become precise estimates; they could be considered accurate reflections of uncertainties. Cost forecasts and DMPs need to evolve as research progresses and as associated data and the

resources and technologies available to manage those data evolve. Monitored evolution of a DMP (e.g., at midterm evaluations or at the end of the award period) might inform eligibility for future funding.

The cost of long-term data stewardship is better considered systematically by the funding institution rather than research by staff. Researchers working in a State 1 environment typically are not responsible for costs or data management beyond the grant performance period. Managing data in States 2 and 3 generally becomes an institutional responsibility, but planning at the institutional level is typically over 1- to 2-year time horizons rather than over the many years required to realize the promise of current and future repositories. A forecaster will focus on costs associated with the resource under development or being managed but needs to be aware of how early planning decisions can affect long-term costs of data curation and use in future states (e.g., by increasing the efficiency of future curation and use or by making future curation prohibitively expensive).

Treating cost estimation as an important agency priority and investing in training, recognizing success, critiquing failures, and encouraging assembly of cost-related data are increasingly important. However, evidence is needed to understand costs. The federal government has an important role in preserving data resulting from scholarly activity. The systematic collection of cost data related to the biomedical-research-data enterprise by an organization that owns that responsibility could provide evidence necessary to translate the cost-forecasting framework presented in this report into a set of tools that can be used by the biomedical-research and data-preservation community. This development could encourage institutions to focus on costs, facilitate future cost forecasting, and help refine cost-forecasting models. The ultimate beneficiaries of such efforts, of course, will be the scientific enterprise and our nation’s citizens, whose well-being science seeks to advance.

REFERENCE

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2020. Planning for Long-Term Use of Biomedical Data: Proceedings of a Workshop. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25707.