Leveraging Unmanned Systems for Coast Guard Missions (2020)

Chapter: Appendix E: Legal and Policy Issues

Appendix E

Legal and Policy Issues

The purpose of this Appendix is to provide further analysis of prevailing legal authorities and policy issues identified in the report and to serve as guidance and a primer upon which the Coast Guard can rely to fully assess current unmanned systems (UxSs) capabilities and develop next steps toward the full range of perceived UxS operations.

Part I builds on the discussion in Chapters 3 and 6 with legal and policy considerations for each UxS domain.

Part II expands on legal and policy considerations and offers a survey of relevant precedent, guidance, and resources to support legal and policy assessments and decision making.

PART I

A discussion of legal and policy considerations for each UxS domain now follows.

Unmanned Maritime Vehicles/Vessels (UMVs)1

Currently, the Coast Guard has no UMVs in its inventory. The Coast Guard has converted a Coast Guard small boat into a remotely controlled/autonomous vehicles, although this is strictly for research and development (R&D) purposes at this point. The Coast Guard Research and Development

__________________

1 For purposes of this Appendix, the term “UMV” is used to encompass all maritime surface watercraft UxS.

Center (RDC) is also testing “contractor-owned and -operated” unmanned surface vehicles (USVs).2 Thus, because the Coast Guard does not currently possess any UxS surface assets, the committee finds no perceived impact to use of such assets in current operations.

However, as the Coast Guard considers investment in UMVs to augment current maritime domain awareness (MDA) operations, the Coast Guard needs to clearly identify what legal requirements must be met for lawful UMV operation under relevant and prevailing authorities in order to identify potential legal obstacles, and if necessary, overcome them.3 To date, the committee understands that the Coast Guard has not developed any formal legal opinions on UMV compliance under prevailing legal frameworks, although sister services and near-peer competitors are developing and utilizing UMVs.4

Specifically, the area of law surrounding UMVs is both emerging and relatively untested as the development of emerging UMV technologies are challenging current applications of legal regimes governing UMV operations, which in turn is spurring significant debate in the domestic and international legal communities. Essentially, technology has outpaced the relevant regulations because existing legal regimes generally contemplated manned ship operations, or at least with a “human in the loop,” when they were initially developed, such as the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea 1972 (COLREGS), Inland Navigation Rules, and United Nations Convention for the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).5 This

__________________

2 UMV testing is being conducted under the RDC’s OTA contract/use agreements with Saildrone Inc. and Spatial Integrated System (https://www.dcms.uscg.mil/Our-Organization/AssistantCommandant-for-Acquisitions-CG-9/Newsroom/Latest-Acquisition-News/Article/2093872/coast-guard-awards-contracts-for-maritime-domain-awareness-study). The text of these OTA contracts was not available to the committee. However, it is the understanding of this committee that the contractors have assumed the risk and responsibility for COLREGS compliance, and thus the Coast Guard’s legal exposure is perceivably limited when contracting with these vendors.

3 For example, the “legal questions and challenges linked to autonomous shipping, as well as the solutions needed to resolve them, will differ depending on what choices are made in relation to manning, crew location, and autonomy level.” Henrik Ringbom. 2019. Regulating Autonomous Ships—Concepts, Challenges and Precedents, Ocean Development & International Law. DOI: 10.1080/00908320.2019.1582593; see also Comité Maritime International. International Working Group Position Paper on Unmanned Ships and the International Regulatory Framework (March 29, 2017). https://comitemaritime.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/CMI-Position-Paper-on-Unmanned-Ships.pdf.

4 UMV-related legal issues are the subject of much academic research and publication in both the United States and internationally (e.g., International Maritime Organization [IMO], Danish Maritime Authority, Port Authority of Singapore).

5 In fact, initial IMO documents on increased automation in shipping were introduced in 1964. See IMCO Doc. MSC VIII/11 (“Automation in Ships”). While related, the COLREGS and UNCLOS are distinct agreements with divergent purposes and effects.

legal conundrum is compounded by the dearth of current precedent directly related to UMV operations on which operators could otherwise rely for guidance.6 Consequently, stakeholders and scholars continue to assess the use of UMV operations under the existing regulations, laws, treaties, and conventions, and they have yet to reach universal consensus.7

As such, one of the most prevalent operational considerations is whether an envisaged platform or watercraft will be deemed a “vessel” because such determination involves questions of fact, law, and policy.8 Therefore, a threshold matter is determining a respective UMV platform’s “legal status” because there are numerous types of UxS platforms that vary in size and capabilities with different designations.9 Furthermore, whether a given UMV is deemed a “vessel” also depends on a review of the context of the purpose, classification, design, and operating characteristics of a respective UMV.10

Of the relevant international conventions, the most formative appear to be the COLREGS that apply “to all vessels upon the high seas and in all waters connected therewith navigable by seagoing vessels,” including warships11 (emphasis added). Notably, while the COLREGS do not specifically preclude operation of UMVs, a Coast Guard UMV would be expected to

__________________

6 See Maritime Law Association of the United States, Response of MLA to CMI Questionnaire re Unmanned Ships, at 12, https://comitemaritime.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/CMI-IWG-Questionnaire-Unmanned-Ships-US.pdf (stating their research “failed to discover any case law spawned by any such collision” of an autonomous ship). In addition, besides the efforts in this space being made in the United States, the legal issues surrounding UMVs are the subject of much academic research and publication, and a topic of great relevance to foreign and international regulators (e.g., IMO, Danish Maritime Authority, Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore).

7 For example, UMV operations may comply with existing rules and laws subject to legal interpretation, perhaps through exceptions or equivalencies under the relevant legal instruments.

8 For example, a status determination assesses the extent to which a UMV will be “1) entitled to exercise certain navigational rights; 2) allowed particular immunities; 3) eligible to carry out a number of important maritime functions; 4) subject to other international maritime legal regimes; and 5) entitled to exercise belligerent rights.” Andrew J. Norris. 2013. Legal Issues Associated with Unmanned Maritime Systems, at 21, U.S. Naval War College, https://works.bepress.com/andrew_norris1/1; see also Daniel Vallejo. 2015. Electric currents: programming legal status into autonomous unmanned vehicles. Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law 47(1):405–428.

9 Terms could include “vessel,” “ship,” “vehicle,” “system,” “device,” or “watercraft,” although maritime laws and rules are largely devoid of reference to watercraft other than “vessels” or “ships.” See Part II for further discussion.

10 The determination of “vessel” status is primarily imputed through U.S. statute (1 U.S.C. § 3) and IMO conventions with reference to definition of “ship” or “vessel.” See Craig H. Allen. 2018. Determining the legal status of unmanned maritime vehicles: formalism vs functionalism. Journal of Maritime Law & Commerce 49:477–514, at 493.

11 See Part II of this Appendix for further discussion on the COLREGS. The COLREGS Inland Rules of Road also apply to all “vessels” upon the inland waters of the United States.

certify the UMV as seaworthy under a preventative layered approach and conform to the general maritime law requiring the exercise of good seamanship in all respects.12 In other words, the COLREGS need to be translated into programming code when integrated into a UMV.13 Such programming could conceivably achieve compliance with certain COLREGS, perhaps through a method which factors in both the strict conformity with the obligatory decision making and historical dependency on human common sense in executing rules in all circumstances.14 In fact, the committee is aware of several technological developers who take the position that compliance with the COLREGS is indeed achievable through programming that allows a UMV to understand and act on a codified set of navigational requirements.15

Thus, to best assess risk and make well-informed decisions, the Coast Guard could develop legal and policy opinions contemplating the legal parameters for each prospective UMV, including how the Coast Guard will ensure legal compliance and whether provisions may be available for exemptions and equivalencies under mandatory instruments, taking into account the applicability and processes related to making, amending, and

__________________

12 COLREGS Rule 2 discusses obligations of good seamanship. Given the rapidly developing advent of UMVs, the issues of whether the COLREGS are still fit for purpose and whether there is no need for the Rules to be totally revised are of much debate in the international legal community. See, for example, “COLREGS: Still Fit for Purpose?” at https://www.maritimeexecutive.com/editorials/colregs-still-fit-for-purpose.

13 See World Maritime University, “Transport 2040 Autonomous Ships: A New Paradigm for Norwegian Shipping—Technology and Transformation” at https://commons.wmu.se/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1072&context=lib_reports.

14 It is worth emphasizing that COLREGS Rules contemplating human interaction or presence would likely be applied differently to a remotely-controlled vessel with a human tasked with controlling or monitoring the vessel as compared to a so-called “fully autonomous” (operating at highest degree of autonomy) vessel.

15 A principle question is to what extent the COLREGS allow or prohibit an artificial intelligence (AI)- or information technology (IT)-driven autonomous collision avoidance system. The Committee is aware of developers in both the military and commercial sectors who have evidenced that compliance with COLREGS through computer algorithms or artificial intelligence is purportedly achievable, see, for example, (1) Mayflower Autonomous Ship, https://newsroom.ibm.com/2020-03-05-Sea-Trials-Begin-for-Mayflower-Autonomous-Ships-AI-Captain; (2) Leidos Sea Hunter, https://www.leidos.com/sites/g/files/zoouby166/files/2019-12/FS-Maritime-Autonomy-Leidos.pdf; (3) Rolls-Royce MAXCMA, https://www.theengineer.co.uk/autonomous-vessels-collisions; (4) Sea Machines 300, https://maritime-executive.com/corporate/sea-machines-names-first-boat-builder-to-offer-autonomous-technology; and (5) Guardian by Marine AI, https://marineai.co.uk/products. The committee has neither requested nor assessed the underlying scientific data that supports these positions.

interpreting treaties.16 Moreover, such determinations could involve a case-by-case threshold “legal status” determination of the respective platform to address the “is it a vessel?” conundrum that considers the size and type of platform, how the platform is utilized, and where the platform is utilized. Of critical import in such an analysis is an assessment of whether a UMV can navigate in a demonstrably safe and prudent manner and whether technical noncompliance is deemed a reasonable legal risk.17

And, as testing of a UMV is integral to assessing its capabilities and legal risk, the Coast Guard could evaluate the use of current U.S. Navy or National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) ranges for testing UMVs.18 The Coast Guard could utilize testing opportunities to clarify to what extent UMVs are subject to and comply with the COLREGS, how legal risk and allocation of responsibilities for gaining relevant use permissions is being obtained, what privileges and immunities are afforded the UMV and operator (e.g., “public vessel”), and which party is responsible for the handling of the data collected.19 The U.S. Navy could be a useful indicator of these issues given their continued growth in

__________________

16 To its credit, the Coast Guard has already developed some legal guidance on vessel status determinations and could build on its historical vessel determination precedent, in particular, the Coast Guard “paddleboard” memorandum of October 3, 2008. That memorandum determined that a paddleboard “is a vessel under 46 U.S.C. §2101,” and more notably, offered a useful multi-prong legal test to assist in determining “what is a vessel.” See Part II for operational factors under current legal precedent.

17 Of note, these legal and policy opinions could include analysis of UMV operations under the various COLREGS Rules, which likely present the most challenges to compliance, including but not limited to Rule 2 (Good Seamanship); Rule 5 (Lookout); Rule 6 (Safe Speed); Rule 7 (Risk of Collision); Rule 8 (Action to Avoid Collision); and Rule 19 (Conduct in Restricted Visibility). The U.S. government has considered options other than definitive COLREGS application for “Unmanned Maritime Systems,” see, for example, Letter from J.G. Lantz, Director, Commercial Regulations and Standards, U.S. Coast Guard, COMDT (CG-5PS), to Ki-tack Lim, Secretary General, International Maritime Organization (Jan. 15, 2016), http://www.imo.org/en/About/strategy/Documents/Member%20States%20-%20tdc/United%20States%20-%20Input%20to%20TDCs.pdf. See Part II for further discussion.

18 Interim guidelines for Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships (MASS) trials, MSC.1/Circ.1604 (14 June 2019), http://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/HotTopics/Documents/MSC.1Circ.1604%20-%20Interim%20Guidelines%20For%20Mass%20Trials%20(Secretariat).pdf.

19 Such legal analysis could assess the potential application of the waiver of sovereign immunity for civil liability in admiralty incidents involving U.S. public vessels under the Suits in Admiralty Act, 46 U.S.C. § 30901–30918 (2018), Public Vessels Act, 46 U.S.C. §§ 31101–31113 (2018), the so-called “Pennsylvania Rule” (The Pennsylvania, 86 U.S. at 125). As UxS platform concepts mature, and in parity with sister services, the Coast Guard could take into account whether arming UxS in support of operations is desirable (i.e., use of warning shots or disabling fire to support Maritime Law Enforcement [MLE], self-defense, etc.). See Part II for further discussion.

the testing of UMVs, in particular because no objections have been raised regarding U.S. Navy UMV operations.20

Ultimately, the legal and policy decisions on UMVs could add value to the Coast Guard in the near term.21 And, it would benefit the Coast Guard if such legal analysis was developed on the recommendations and guidance of senior decision makers within the organization with clearly articulated parameters for an intended UMV operation.22

Unmanned Underwater Vehicles (UUVs)

In terms of UUV, the Coast Guard possesses 12 tethered remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) referred to as the “Fusion” manufactured by Strategic Robot Systems. And, the Coast Guard RDC has started a project to coordinate and conduct lab and field tests of long-range autonomous underwater vehicles, remote environmental monitoring units, autonomous underwater vehicles and unmanned aircraft systems (UASs) in ice conditions to verify accuracy of sensors and UxSs.23

__________________

20 A Ghost Fleet Overlord unmanned surface vessel (USV) conducted a roundtrip 1,400 nautical mile voyage from the Gulf Coast to Norfolk, Va., while autonomously navigating and following COLREGs to safely operate among commercial traffic. See https://news.usni.org/2020/06/23/program-office-maturing-usvs-uuvs-with-help-from-industry-international-partners; see also “Sea Hunter USV Autonomously Navigates from California to Hawaii,” at https://www.unmannedsystemstechnology.com/2019/01/sea-hunter-usv-autonomouslynavigates-fromcalifornia-to-hawaii; Other international strategic partners are also developing UxS (e.g., UUV, USV), such as the UK, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and Singapore (e.g., Singapore Navy Protector USV was deployed for maritime surveillance and force protection duties in the Northern Arabian Gulf and the Gulf of Aden, https://www.mindef.gov.sg/oms/navy/careers/our-assets/protector-unmanned-surface-vessel.html#:~:text=Our%20Assets-,Protector%20Unmanned%20Surface%20Vessel,or%20from%20ships%20at%20sea).

21 For example, COLREGS Rule 5 (Lookout) “presents a rule-based challenge for direct application to UMSs, which can be overcome by a broad reading of the rule or an amendment that exempts UMSs from Rule … a broad reading of Rule 5, considering sensors the functional equivalent of ‘sight and hearing,’ is reasonable, noting that UMSs are being developed with sensors advanced enough to meet judicial requirements for the Rule.” Christopher C. Swain, 2018. Towards greater certainty for unmanned navigation, a recommended United States military perspective on application of the “Rules of the Road” to unmanned maritime systems. Georgetown Law Technology Review 3:119–161, at 141.

22 It bears emphasis that ambiguity in classifying a respective surface platform could prove useful depending if, for example, the Coast Guard finds that a respective fit-for-purpose “vessel” is unable to fully comply with the COLREGS and undue risk of negligent operations exists, and designation as a “vehicle” or other similar term aligns more appropriately with the intended purpose of the UxS. For a more fulsome analysis of this issue, see Part II.

23 The U.S. Department of Homeland Security Science & Technology Directorate posted a Request for Information for a project (conducted on behalf of the Coast Guard) exploring use of long-range autonomous underwater vessels for detection and mapping of oil spills on the surface and subsurface and under ice.

However, such subsurface operations generally fall outside the purview of the COLREGS, and thus there are little to no perceived legal impediments to such operations.24 However, the Coast Guard could still conduct an operational assessment for such types of subsurface and tethered remotely operated vehicle operations to review the varying levels of risk. And, as the U.S. Navy and NOAA are currently utilizing prototype UUVs, maintaining a collaborative approach and close communications with these entities could benefit the Coast Guard as a way to leverage lessons learned and best practices in development of the means to meet legal compliance.25

Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UASs)

The Coast Guard has the legal authority, if not the capacity yet, to deploy UASs26 in domestic and international airspace subject to compliance with governing rules.27 As with UMVs, UAS technology has outpaced regulations, and consequently while the Coast Guard has legal authority to operate UASs for MDA, current legal regimes do not enable unrestricted UAS support of Coast Guard MDA operations.

As detailed in Chapter 4, the Coast Guard has deployed contractor-owned and -operated medium-range UASs on National Security Cutters (NSCs) in offshore areas, and has provided commercial off-the-shelf short-range small UASs (sUASs)28 to seven field units for use in domestic airspace through the Group-1 UAS Prototype Program Initiative.29 In 2018, the Coast Guard conducted maritime-based Drone Evaluations and Training at Singing River Island (Pascagoula, Mississippi) to evaluate mapping

__________________

24 Part XIII of UNCLOS does provide some guidance on subsurface operations for scientific research purposes. See https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf.

25 See, for example, NOAA Unmanned Systems Strategy (February 2020), at https://nrc.noaa.gov/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=0tHu8Kl8DBs%3D&tabid=93&portalid=0.

26 For purposes of this section, the term UAS is used as defined in COMDTINST M3710.1H as “an unmanned aircraft and the equipment necessary for the safe and efficient operation of that aircraft. An unmanned aircraft is a device that is used, or is intended to be used, for flight in the air with no onboard pilot.” Other terms include UAV, drone, remotely piloted vehicle, remotely piloted aircraft, and remotely operated aircraft.

27 14 C.F.R. § 91.101 (“Flight Rules”) prescribes flight rules governing the operation of aircraft within the United States and within 12 nautical miles from the coast of the United States. However, regulations that include the term “civil aircraft” in their applicability do not apply to public aircraft operations (e.g., 14 C.F.R. Part 91).

28 Per 14 C.F.R. § 1.1, “small unmanned aircraft” means an unmanned aircraft weighing less than 55 lb. on takeoff, including everything that is on board or otherwise attached to the aircraft.

29 ALCOAST 004/18 - JAN 2018 AUTHORIZED USE OF COAST GUARD UNMANNED AIRCRAFT SYSTEMS (UAS), at https://content.govdelivery.com/accounts/USDHSCG/bulletins/1d0fcb5.

technologies to support missions such as oil spill response, search and rescue, and post-storm damage assessment.30 Currently, Coast Guard personnel (4 pilots and 10 sensor operators) serve in the CBP-USCG UAS Joint Program Office, which is operating Long-Range UAS MQ-9 Predator to provide land and MDA in support of (1) southern border and littoral surveillance and (2) Joint Interagency Task Force South; however, all MQ-9 aircraft, ground control stations, and equipment in that program are owned by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP).

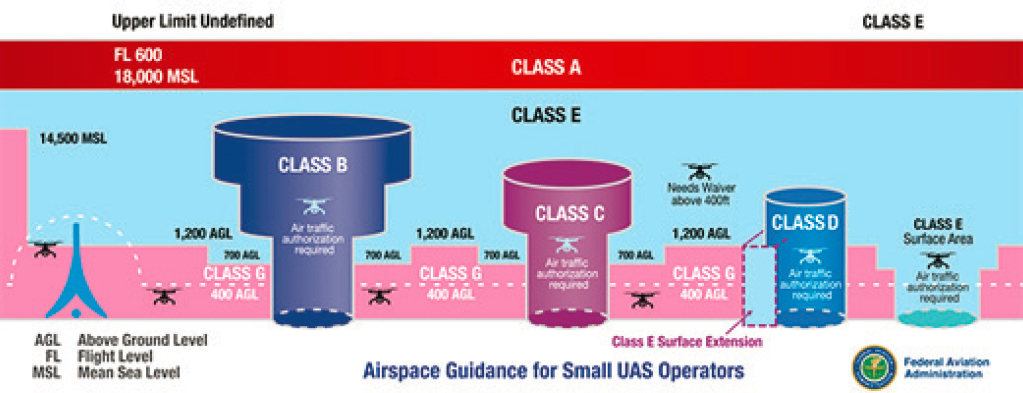

A UAS is considered an “aircraft” as defined in the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA’s) authorizing statutes,31 and therefore Coast Guard UAS operations in the National Airspace System (NAS)32 are subject to FAA regulations.33 The FAA imposes stringent legal requirements that restrict government operations of UASs to personnel who have UAS pilot licenses, and there are numerous rules concerning where UASs can be flown.

More specifically, no person may operate a UAS in the NAS without specific authority, and consequently, the Coast Guard generally has three options to lawfully operate a UAS in the NAS under the prevailing FAA regulations:

- Voluntarily adhere to the flight rules under 14 C.F.R. part 107 (“Part 107”). The Part 107 operating rules allow operations of UAS weighing less than 55 lb. at or below 400 ft. above ground level for visual line-of-sight (VLOS) operations during daylight hours only. The rules also address airspace restrictions and pilot certification.

- Fly under the statutory requirements for public aircraft operations (PAO) (49 U.S.C. § 40102(a) and § 40125). Operate with a Certificate of Waiver or Authorization (COA) to be able to self-certify UAS and operators for flights performing governmental functions. For UAS PAO, the specific authority required is the COA.

__________________

30 U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Snapshot: Testing and Training with Drones. https://www.dhs.gov/science-and-technology/news/2018/04/23/snapshot-testing-and-training-drones.

31 49 U.S.C. § 40102(a)(6).

32 The NAS is “the common network of U.S. airspace; air navigation facilities, equipment and services, airports or landing areas … shared jointly with the military.” See http://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/media/pcg_4-\03-14.pdf.

33 The FAA is the federal agency responsible for maintaining the safety and efficacy of the U.S. aviation system. Pursuant to 49 U.S.C. § 40103, the FAA has exclusive sovereignty over domestic airspace from “the ground up,” and thus regulates UAS/UAV/remotely piloted aircraft as “aircraft.” Domestic airspace is the airspace above U.S. territory and extends 12 nautical miles from shore.

- Obtain a blanket public COA, which would permit nationwide flights and the option to obtain emergency COAs under special circumstances.34

Although the Coast Guard may lawfully operate sUASs for MDA in domestic airspace subject to the above requirements, some regulatory limitations present a legal barrier to expanded flight operations. The most notable of these limitations is the requirement under Part 107 that the remote pilot in command, the visual observer (if one is used), and the person manipulating the flight control of the sUAS must be able to maintain VLOS of the sUAS throughout the entire flight.35 Other limitations under Part 107 include restrictions on operations from a moving vehicle or aircraft (§ 107.25),36 daylight-only operations (§ 107.29), operations over people (§ 107.39), operation in certain airspace (§ 107.41) and general operating limitations (§ 107.51).37 Also, the United States is still developing a capability to effectively manage national airspace UAS traffic, commonly referred to as the UAS Traffic Management infrastructure.38 Thus, some regulatory limitations may present a barrier to the Coast Guard’s ability to execute its full range of contemplated UAS capabilities for MDA.

Generally, when Coast Guard aircraft are operated in accordance with titles 10, 14, 31, 32, or 50, and when not used for commercial purposes, Coast Guard UAS qualify as PAO.39 PAO are limited by statute to certain government operations within U.S. airspace and must comply with certain general operating rules applicable to all aircraft in the NAS. The FAA has limited oversight of PAO, although such operations must continue to comply with the regulations applicable to all aircraft operating in the NAS, and

__________________

34 The Coast Guard has a blanket FAA UAS COA (Blanket Area-Public Agency, 2019-AHQ-100-COA) for operations in Class G airspace allowing the Coast Guard to operate UAS up to 1,200 ft. See also Appendix (D) to COMDTINST M3710.1H.

35 14 C.F.R. § 107.31.

36 See, for example, “Planck Aerosystems, the First Autonomous Drone Company That Developed the Ability to Launch and Land Drones on a Moving Vehicle and Boats, Lands $2 Million Contract with DoD,” at https://techstartups.com/2019/09/30/planck-aerosystems-first-autonomous-drone-company-developed-ability-launch-land-drones-moving-vehicle-boats-lands-2-million-contract-dod.

37 Group-1 UAS Prototype Program Initiative units were provided with the Yuneec Typhoon-H hexacopter, and the units were limited by the operational constraints established in FAA Part 107 including daytime operations, maximum altitude of 400 ft., and within VLOS only. See U.S. Coast Guard. January 2019. Group-1 UAS Prototype Program Initiative (GUPPI) Operational Evaluation and Testing of Short-Range UAS (SR-UAS) at Various Geographical Locations. USCG CG-711 Report.

38 U.S. Department of Homeland Security Science & Technology Directorate. Snapshot: Working with NASA to Secure Drone Traffic. https://www.dhs.gov/science-and-technology/news/2019/02/12/snapshot-working-nasa-secure-drone-traffic.

39 49 U.S.C. § 40125(c). Public aircraft status exists only within U.S. airspace.

the Coast Guard remains responsible for oversight of the operation, including aircraft airworthiness and any operational requirements.40

The COA process establishes mandatory provisions to ensure that the level of safety for domestic UAS flight operations is equivalent to that of manned aviation. COAs are unique to the intended mission and specifies the time period, location, circumstances, and conditions under which the UAS must be operated; and, are not required for UAS operations within special use airspace or Due Regard operations beyond 12 nautical miles from shore.41

Furthermore, in international airspace,42 the Coast Guard possesses the authority and ability to operate UASs, although similar legal restrictions exist as in domestic airspace on achieving full use of UASs. When operating outside the NAS, Coast Guard UASs are required to operate in accordance with appropriate international authorities, specifically, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) flight rules that govern operations in international airspace.43 When UAS operations from a Coast Guard cutter (e.g., NSC) cannot comply with ICAO regulations, Coast Guard UASs are required to operate with Due Regard for the safety of all other aircraft consistent with Operations Not Conducted Under ICAO Procedures and DoDI 4540.01.44 When Due Regard operations are conducted, full responsibility for separation between Coast Guard aircraft and all other aircraft, both public and civil, falls on the Coast Guard—operational airspace deconfliction is the responsibility of the operational and tactical commanders.

Notably, tactical aircraft operations from cutters usually cannot be conducted in compliance with ICAO regulations when deemed not practical

__________________

40 For a summary of PAO, see FAA Advisory Circular No: 00-1.1B “Public Aircraft Operations—Manned and Unmanned,” at https://www.faa.gov/documentLibrary/media/Advisory_Circular/AC_00-1.1B.pdf.

41 In this regard, the Coast Guard has developed comprehensive guidance regarding UAS flight authorizations, for example, before conducting UAS operations within the NAS outside of special use airspace, a flight clearance shall be obtained from CG-711. See also COMDTINST M3710.1 H, App. D(A)(5) and “General Flight Rules” (Ch. 4(C)): Coast Guard aircraft [including UAS] flights “shall be conducted in accordance with the rules, regulations, or recommended procedures specified by the publications in the following rank ordered list. Where conflicting regulations or varying procedures exist, the higher ranking publication shall be followed: Coast Guard; Directives; Federal Aviation Regulations, 14 C.F.R. § 91 and 97 and FAA Manuals; Joint FAA/Military Documents; DOD Publications.”

42 Generally defined as airspace greater than 12 nautical miles from shore.

43 See Annex II of the Convention on International Civil Aviation (Chicago Convention); see also 14 C.F.R. § 91.

44 See U.S. Department of Defense Instruction (DoDI) 4540.01 (Use of lnternational Airspace by U.S. Military Aircraft and for Missile and Projectile Firings), at https://www.hsdl.org/?abstract&did=801464.

and compatible with the mission.45 Notably, Due Regard may be exercised by utilizing “alternative means” if approved by the appropriate authority, and obligations may be met using analytic methods such as airspace density analyses, ground-based sense-and-avoid radar systems, and other approved procedures or technologies. More specifically, for UAS to comply with Due Regard provisions, one of the following provisions must be met:

- The UAS must be operated in visual meteorological conditions and the airspace around the sUAS must be under constant VLOS observation from the aircraft commander or a visual observer in communication with the aircraft commander.

- The UAS may be temporarily operated in less than visual meteorological conditions when required by operational needs if the aircraft commander determines that there is acceptable risk to other aircraft. The aircraft commander must utilize all available resources and information in assessing an acceptable level of risk before conducting such operations with due regard for all other aircraft. Any aircraft operations in reduced visibility must be of no greater extent or duration than required.

- The UAS must be under continuous surveillance by, and in communication with, the cutter or other surface or airborne facility providing the surveillance. This is typically satisfied by the NSC’s air surveillance radar to allow for beyond visual line of sight operations.

- The UAS must be equipped with a Military Department-certified system that is sufficient to provide separation between itself and other aircraft.46

To conduct successful beyond VLOS flight operations from a cutter (a desirable facet of expanding MDA), achieving and maintaining satisfactory Due Regard compliance is critical. To this end, the Coast Guard currently relies on shipboard air search radar (ASR) to ensure continuous surveillance by, and in communication with, the cutter or other surface or airborne facility providing the surveillance.47 Thus, during UAS operations the ASR

__________________

45 COMDT (CG-7) Memorandum (Dec. 23, 2018), CUTTER-BASED SMALL UNMANNED AIRCRAFT SYSTEMS (sUAS) CONCEPT OF OPERATIONS (CONOPS) AND VIGNETTES.

46 DoDI 4540.01; see also CUTTER-BASED SMALL UNMANNED AIRCRAFT SYSTEMS (sUAS) CONCEPT OF OPERATIONS (CONOPS) AND VIGNETTES (CG-711 Memo 3710).

47 For example, ScanEagle’s sensors provides a 20 nautical mile swath of sight. See DoDI 4540.01, 3.c.(1)(a): Aids to visual observation, such as binoculars or periscopes, may be employed consistent with the applicable Military Department’s guidance.

is critical to Due Regard compliance as such operations could be restricted in instances where the ASR is inoperable.48

Counter-Unmanned Aerial Systems (C-UASs)

Several U.S. laws generally prohibit the use of C-UAS technology in the United States, which were developed to protect the NAS, civil use of electromagnetic spectrum, and constitutional and privacy rights of U.S. persons.49 Nonetheless, the Coast Guard has narrowly defined authority to use kinetic means for C-UAS sunder applicable law and policy, subject to applicable restrictions and policies.50 For example, while the Coast Guard has the authority to establish a safety zone in navigable waters or a security zone in land and water, only the FAA may regulate or secure the airspace above the respective safety or security zone. Accordingly, attempts to restrict small sUAS operations in the maritime domain must include consultation with the FAA (and interagency partners as applicable).51

The Coast Guard has been developing its capacity to utilize C-UASs over the past several years, and as the C-UAS programs mature, it would be beneficial for the Coast Guard to develop more legal and policy work to support their deployment and operations. In June 2017, Coast Guard began to pursue C-UAS authorized actions under the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) to support its maritime escort mission, whereby certain DOD assets require Coast Guard escorts when operating in and out of their homeports.52 The Coast Guard obtained express authority to counter

__________________

48 See DoDI 4540.01 and CGC STRATTON memo 3500 dated November 28, 2017 (FOUO); see also Coast Guard Maritime Security Cutter, Large (WMSL) Class ScanEagle (SE) Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) Standard Operating Procedures (SOP), CG-711 NOTICE 3710 dated July 11, 2017; see also DOD General Planning (GP) Flight Information Publication (FLIP), Chapter 8, or DoDI 4540.01, Operations Not Conducted Under ICAO Procedures. COMDTINST M3710.1H, App. D.

49 See Part II for a survey of applicable C-UAS laws; see also FAA Law Enforcement Guidance for Suspected Unauthorized UAS Operations (Version 5), issued August 14, 2018, at https://www.faa.gov/uas/public_safety_gov/media/FAA_UAS-PO_LEA_Guidance.pdf.

50 See DHS Counter Unmanned Aircraft Systems Legal Authorities, at https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/dhs_cuas-legal-authorities_fact-sheet_190506-508.pdf. The DHS Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) is taking a lead in many of these C-UAS activities https://www.cisa.gov/publication/uas-fact-sheets.

51 In support, the developing Remote Identification (Remote ID) rule will require UASs in flight to provide identification information to address safety, national security, and law enforcement concerns and also enable federal security agencies (Coast Guard) to better assess threats when a UAS appears to be flying in an unsafe manner or where the UAS is not allowed to fly. See Remote Identification of Unmanned Aircraft Systems (FAA-2019-1100), at https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=FAA-2019-1100-0001.

52 See Title 10 U.S.C. § 130i (Protection of Certain Facilities and Assets from Unmanned Aircraft).

illicit UAS activity, although such capabilities were limited because the C-UAS authority was either restricted to a specific mission or under the auspices of another department.53 In support, Coast Guard use of force (UOF) Policy and Maritime Security and Response Operations (MSRO) Policy Letter 02-18 authorizes Coast Guard operational units to employ readily available kinetic means in defense of self/others critical infrastructure. In international waters, there are no restrictions on the use of C-UAS technology that operates on the radio frequency (RF) or global positioning system (GPS) spectrum, and when the Coast Guard is operating under DOD Tactical control, Coast Guard Patrol Forces Southwest Asia (PATFORSWA) cutters may employ kinetic and non-kinetic (i.e., C-UAS) means to counter UAS pursuant to DOD guidance.54 And, Maritime Force Protection Units are authorized to use C-UAS technology in accordance with MSRO Policy Letter 06-18 only in defense of self/others or critical infrastructure.

Notably, on October 5, 2018, the President signed into law the Preventing Emerging Threats Act of 2018 (the act), the first statutory grant of authority for the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to explicitly counter UAS threats.55 This law permits authorized DHS personnel to take protective measures that are necessary to mitigate a credible threat that an unmanned aircraft or UAS poses to the safety or security of a covered facility or asset and permits authorized DHS component personnel to detect, identify, monitor, and track UAS without prior consent; warn the operator of a UAS, including by electromagnetic means; disrupt control, seize control, or confiscate a UAS without prior consent; and use reasonable force to disable, damage, or destroy a UAS. The DOJ Guidance to Protect Facilities from Unmanned Aircraft and Unmanned Aircraft Systems further supports and clarifies the Coast Guard’s C-UAS authority.56

Currently, Coast Guard is conducting an operational pilot to “test and evaluate C-UAS capabilities used to detect, identify, and mitigate UAS that

__________________

53 Department of Homeland Security Office, Inspector General. June 25, 2020. DHS Has Limited Capabilities to Counter Illicit Unmanned Aircraft Systems. DHS OIG Report OIG-2043. https://www.oig.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/assets/2020-06/OIG-20-43-Jun20.pdf.

54 See 10 U.S.C. § 130i: authority to take actions to mitigate threats posed by unmanned aircraft to safety and security of a “covered asset or facility” that directly relates to select mission areas, including nuclear deterrence/missile defense.

55 Codified at 6 U.S.C. § 124n; https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=granuleid:USCprelim-title6-section124n&num=0&edition=prelim.

56 Guidance Regarding Department Activities to Protect Certain Facilities or Assets from Unmanned Aircraft and Unmanned Aircraft Systems (April 13, 2020), https://www.justice.gov/ag/page/file/1268401/download; https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/attorney-general-barr-issuesguidance-protect-facilities-unmanned-aircraft-and-unmanned.

pose a credible threat to “covered facilities or assets.”57 And, the Coast Guard RDT&E is conducting projects on maritime C-UAS and airborne C-UASs.58 While the Coast Guard has relatively limited authorities for use of C-UASs, these authorities are still somewhat restricted and evolving, and thus the Coast Guard could ensure that a legal assessment has been completed related to the designing, testing, procuring, and use of C-UAS technology to ensure compliance with applicable laws and DHS/Coast Guard policies.

PART II

A survey of relevant authorities, precedent, guidance, and resources that may be useful to assess Coast Guard UxS legal and policy considerations now follows.

Legal Authority Overview

Relevant Coast Guard authorities related to execution of its 11 statutory missions include but are not limited to:

- Primary Duties of the Coast Guard. Sets out the primary duties of the Coast Guard, including its role as a specialized service in the Navy during time of war. 14 U.S.C. 2; See generally 33 C.F.R. 1-199; 46 C.F.R. 1-199; 33 C.F.R. Part 1; and 46 C.F.R. Part 2.

- General Functions and Powers. Sets out the general functions and powers of the Coast Guard including establishing aids to navigation, controlling the movement of vessels, conducting oceanographic research, saving life and property at sea, and enforcing federal law. 14 U.S.C. 81, 88, 89, 91, and 94; Executive Order (E.O.) 7521 (covering the use of vessels for ice breaking operations in channels and harbors); 6 U.S.C. § 468 (2017), Homeland Security Act, Pub. L. No. 107-296, § 888, 116 Stat. 2135, 2249-50 (2002).

- Commandant; General Powers (Testing). For the purpose of executing the duties and functions of the Coast Guard the Commandant

__________________

57 See Privacy Impact Assessment for the U.S. Coast Guard Counter-Unmanned Aircraft Systems Pilot DHS/USCG/PIA-030, October 28, 2019, at https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/privacy-pia-uscg030-cuas-october2019.pdf. The Coast Guard will conduct the pilot testing through 2020, after which its C-UAS program may become fully operational.

58 Respectively, (1) Project #7812: Methods to detect, track, identify, and defeat illicit use of unmanned aircraft systems in the maritime environment and (2) Project #7821: Technology and tactics to secure airspace from small Unmanned Aircraft Systems (sUAS). See https://www.dcms.uscg.mil/Portals/10/CG-9/Acquisition%20PDFs/FY20%20RDTE%20Project%20Portfolio.pdf?ver=2019-10-24-154528-393.

- may conduct experiments and investigate, or cause to be investigated, plans, devices, and inventions relating to the performance of any Coast Guard function, including research, development, test, or evaluation related to intelligence systems and capabilities. 14 U.S.C. 504(a)(4).

- Coast Guard as an Armed Force. The Coast Guard is a military service and at all times a branch of the armed forces in the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, except when operating as a service in the Navy; and sets out policies concerning the Coast Guard’s role as a service in the Navy during time of war. 14 U.S.C. § 1, 3, 4; 10 U.S.C. 101(a)(4). See generally 33 C.F.R. 1–199; 46 C.F.R. 1–199; 33 C.F.R. Part 1; 46 C.F.R. Part 2. It is the only armed force with organic law enforcement authority. See also Pub. L. No. 107-296 (The Homeland Security Act), establishing the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and providing the organic parameters and authorities related to the agency.

- Vessel Boardings. The Coast Guard may board any vessel subject to the jurisdiction of the United States, whether on the high seas, or on waters over which the United States has jurisdiction, to make inquiries, examinations, inspections, searches, seizures, and arrests for the prevention, detection, and suppression of violations of U.S. laws. 14 U.S.C. § 89.

- Navigation Safety. The Coast Guard maintains broad authority over navigation safety in the navigable waters of the United States, including the ability to order vessels to operate as directed. 33 U.S.C. § 1223.

- Naval Safety and Security. The Coast Guard can control the anchorage and movement of vessels in the navigable waters of the United States to ensure the safety and security of U.S. naval vessels. 14 U.S.C. § 91.

- Waterway Security. When the President determines that U.S. national security is endangered, the Coast Guard may enforce regulations concerning the movement or anchorage of vessels within U.S. territorial waters, including vessel seizure and forfeiture, and may fine and imprison the master and crew for noncompliance. 50 U.S.C. § 191.

- Assistance. The Coast Guard may use its personnel and facilities to assist federal, state, and local agencies when Coast Guard assets are especially qualified to perform a particular activity. 14 U.S.C. § 141; see also 14 U.S.C. 142–148.

- Pollution Response. The Coast Guard may respond to discharges or threats of discharges of oil and hazardous substances into the

- navigable waters of the United States and promulgate certain pollution prevention regulations. 33 U.S.C. § 1321.

- Vessel Inspections. The Coast Guard prescribes regulations for the inspection and certification of vessels. 46 U.S.C. § 3306.

- Customs. The Coast Guard has the authority to enforce customs laws, including anti-smuggling regulations. U.S.C. Title 19.

- Maritime Security. The Coast Guard has a key role in preventing maritime transportation security incidents, which includes the implementation of international security standards. 46 U.S.C. VII.

- Intelligence Community. The Coast Guard is a member of the intelligence community. U.S.C. Title 50.

- Living Natural Resources. The Coast Guard safeguards fisheries and marine-protected resources by enforcing living natural resource authorities such as the Magnuson-Stevens Fisheries Conservation and Management Act 16 U.S.C. § 1801, the Lacey Act 16 U.S.C. §§ 3371–3378, the Endangered Species Act 16 U.S.C. §§ 1531–1544, and the National Marine Sanctuaries Act 16 U.S.C. §§ 1431–1445.

Maritime Zones and Airspace Boundaries

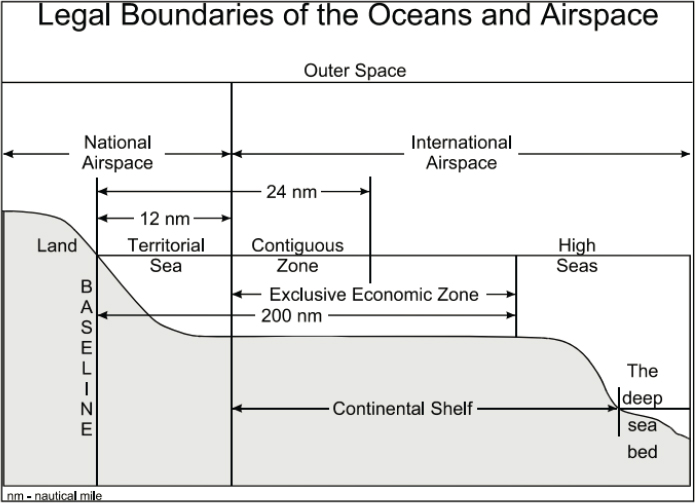

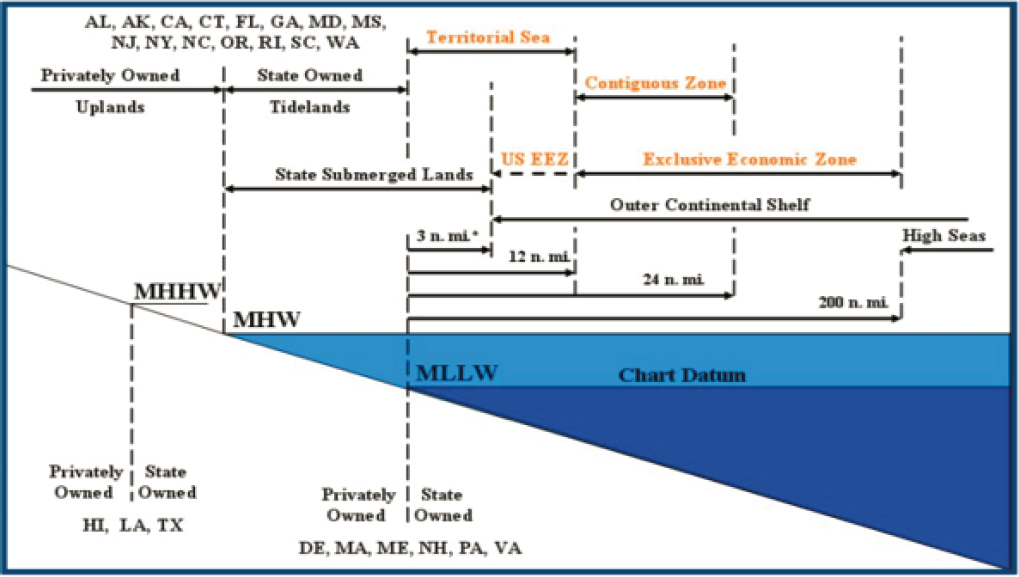

The Coast Guard operational areas overlap with recognized U.S. and international geographic regimes, and thus add to jurisdictional complexity. Therefore, it is imperative to understand the maritime zones and airspace in which Coast Guard UxS operations will be conducted throughout the maritime domain to ensure compliance with applicable laws and regulations.59 To this end, the United Nations’ Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) Convention provides relevant jurisdictional classifications for sea boundaries and airspace:60

- Baseline (0 Nautical Miles). The boundary line dividing the land from the ocean as marked on charts, typically described as the low waterline along the coast.

__________________

59 See NOAA Office of General Counsel website “Maritime Zones and Boundaries,” at http://www.gc.noaa.gov/gcil_maritime.html; see also Coast Guard Publication 3-0, Operations (February 2012), Ch. 3.2.

60 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, Dec. 10, 1982, 1833 U.N.T.S. 3, 21 I.L.M. 1261, entered force Nov. 1, 1994. https://www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf. The United States is not a party to UNCLOS, although since 1983 it has asserted that the navigation and overflight provisions of the convention are reflective of customary international law, and thus the United States operates in conformity with those provisions. Ronald Reagan, Statement by the President, 19 WEEKLY COMP. PRES. DOC. 383 (March 10, 1983); see also U.S. Department of State Office of Ocean and Polar Affairs “Law of the Sea” and “Limits of the Sea,” https://www.state.gov/key-topics-office-of-ocean-and-polar-affairs/#law.

- Internal Waters. All U.S. waters shoreward of the baseline, including all waters on the U.S. side of the international boundary of the Great Lakes.

- State Waters (0–3 Nautical Miles; 0–9 Nautical Miles for Florida and Texas and Gulf Coast). State-managed waters historically related to areas of public interest such as fishing, cultural heritage, recreation, environmental protection, and commerce.

- The Territorial Sea/National Airspace (0–12 Nautical Miles). The waters within the belt that is 12 miles wide and adjacent to the U.S. coast measured seaward from the baseline. For the purpose of enforcing some domestic U.S. laws, the territorial sea extends only 3 miles seaward of the baseline. Under the Chicago Convention, “National Airspace” composes the land and territorial waters, thus the non-sovereign portion of airspace is beyond 12 nautical miles.61

- Customs Waters. Generally defined as the waters shoreward of a line drawn 12 miles from the baseline (including territorial sea and inland waters with ready access to the sea).

- Contiguous Zone (12–24 Nautical Miles). Area adjacent to the territorial sea and extending 24 nautical miles from the baseline over which a nation exercises control over laws related to customs, sanitary, fiscal matters, and immigration. The airspace beyond 12 nautical miles from land is considered international airspace.

- Exclusive Economic Zone (“EEZ”) (12–200 Nautical Miles). An area adjacent to the territorial sea and extending 200 nautical miles from the baseline over which a nation exercises control necessary to protect exploration, exploitation, conservation, and management of living and nonliving natural resources within the waters, seabed, and subsoil of the zone.

- International Waters. Waters seaward of the outer limit of the territorial sea of any nation, but including the high seas, EEZ, and contiguous zones (when claimed seaward of the territorial sea).

- High Seas (Beyond 200 Nautical Miles). Areas of the ocean beyond domestic jurisdiction.

Figures E-1 and E-2 illustrate the legal boundaries ocean and airspace.

__________________

61 The Convention on International Civil Aviation (“Chicago Convention”) also provides context on these boundaries, International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), Convention on Civil Aviation (“Chicago Convention”), December 7, 1944, (1994) 15 U.N.T.S. 295, https://www.icao.int/publications/pages/doc7300.aspx. While the Chicago Convention and its Annexes, including Annex 2, are generally not applicable to State aircraft (e.g., military), the Convention does place requirements on States regarding the interaction between military and civil aircraft.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Defense.62

Legal Considerations for UMV

As discussed in Chapters 3 and 6 and Part I, in order to determine legal rights and obligations when operating a particular UMV, a threshold issue will be how to characterize the UMV given the language in key domestic statutes, regulations, and international laws, which primarily govern operations by “vessels” or “ships.”63 Efforts toward compliance with governing legal authorities has invariably raised issues of fact, policy, and law, including the critical question of “is it a vessel?”

Adding to the complexity of this legal status determination, industry and military services alike have been developing a range of terminology used in describing UMVs, often depending on the degree of autonomy the vehicle has, whether it is used in combat, and whether it is below, on, or above the surface of the water. To illustrate, the literature supporting this

__________________

62 U.S. Department of Defense. 2007. “The Commander’s Handbook on the Law of Naval Operations.” https://www.jag.navy.mil/documents/NWP_1-14M_Commanders_Handbook.pdf.

63 The literature indicates that terms used to describe a UxS have been varied, including but not limited to ship, watercraft, vessel, vehicle, system, object, device, equipment, flotsam/jetsam, contrivance, and marine debris.

SOURCE: NOAA Office of Coast Survey.64

__________________

64 National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. “Maritime Zones of the United States.” https://nauticalcharts.noaa.gov/data/docs/gislearnaboutmaritimezones1pager.pdf.

report has revealed there is no universally accepted name for an unmanned maritime vehicle (UMV), and the general position in the governmental, scientific, legal, and technical communities has yet-to-be aligned as illustrated by the following non-exhaustive list:

- Anti-Submarine Warfare Continuous Trail Unmanned Vessel (ACTUV)

- Autonomous Sea Drone (ASD)

- Autonomous Surface Vehicle (ASV)

- Autonomous Underwater Vehicle (AUV)

- Highly Automated Ship System (HASS)

- Marine Unmanned Vehicle

- Marine Unmanned Vessel

- Maritime Autonomous Surface Ship

- Maritime Autonomous Vehicle

- Merchant Autonomous Surface Ship (MASS)

- Ocean Data Drone

- Optionally Manned Vessel (OMV)

- Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV)

- Ship with Periodically Manned Bridge

- Smart Ships

- Uncrewed Surface Vessel

- Unmanned Combat Surface Vehicle (UCSV)

- Unmanned Combat Underwater Vehicle (UCUV)

- Unmanned Combat Vehicle (UCV)

- Unmanned Craft (UC)

- Unmanned Maritime System (UMS)

- Unmanned (or Crewless) Maritime Vehicle (UMV)

- Unmanned Surface Robot (USR)

- Unmanned Surface Vehicle (USV)

- Unmanned Underwater (or Undersea) Vehicle (UUV)

- Unmanned Vehicle (UV)

For an example of classification of autonomous maritime systems and autonomous ship types see Figure E-3.

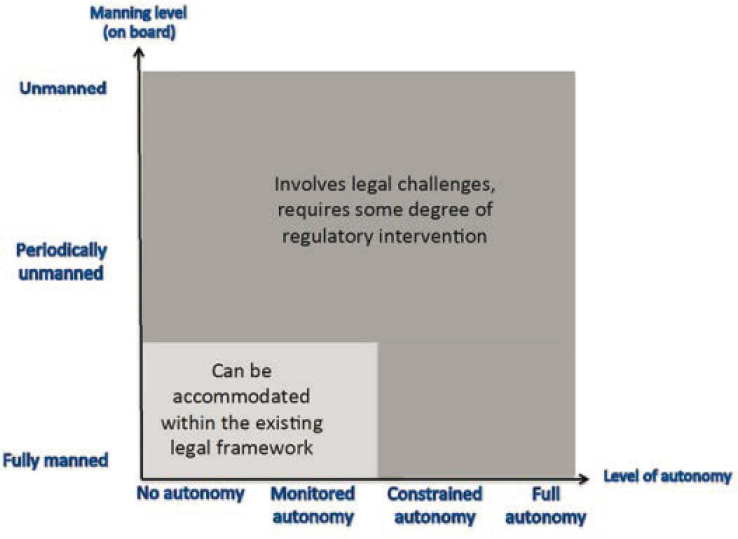

To this end, a key legal consideration will be whether the Coast Guard procures and operates a platform characterized or classified as listed above taking into account the level of autonomy (or advanced automation) at which the UxS intends to operate since this will be relevant to how a respective platform fits into the prevailing legal framework. Observations on the “legal challenge involved” are illustrated in Figure E-4.

SOURCE: Norwegian Forum for Autonomous Ships (NFAS).65

__________________

65 Norwegian Forum for Autonomous Ships. “Definitions for Autonomous Merchant Ships,” p. 7, Fig. 4, http://nfas.autonomous-ship.org/resources/autonom-defs.pdf.

SOURCE: Henrik Ringbom.66

Considering the consequences under domestic and international law and in support of maintaining a rules-based order in the maritime domain, the Coast Guard’s contemplated operations may require addressing key questions such as the following:67

- What markings and insignia must a UMV carry and display?

- What navigation rights does a UMV have on the high seas and in coastal State waters?

- What are the UMV’s obligations with respect to other vessels and mariners?

__________________

66 H. Ringborn. 2019. Regulating autonomous ships—concepts, challenges and precedents. Journal of Ocean Development & International Law 50(2–3):8. https://www.jus.uio.no/nifs/english/research/events/2019/regulating-autonomous-ships-concepts-challenges-and-precedents.pdf.

67 List adopted from Craig H. Allen, Determining the legal status of unmanned maritime vehicles: formalism vs functionalism, Journal of Maritime Law & Commerce 49:488–490, at 477 (including more expansive list of similar questions).

- Can a UMV be employed in law enforcement actions, including in hot pursuit (see UNCLOS Article 111)?

- Must UMV shoreside operators hold a crewmember rating (e.g., boatswain)?

- Is the shoreside operator of a remotely-controlled UMV the craft’s “Commanding Officer”?

- What is the role of the programmer (or program team) of a fully autonomous UMV in determining responsibility for decision making?

- Do government-owned UMVs have sovereign immunity as warships, or are they subject only to “sovereign ownership” immunity as U.S. property?

In support of this analysis, there are several sources of authority on which the Coast Guard may rely to assist with the threshold question of whether a UMV is a “vessel,” including international law, domestic law, and U.S. policy.

International Legal Framework

- Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, art. 31, May 23, 1969, 1159 U.N.T.S. 331, entered into force Jan. 27, 1980.

- 1982 U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), Dec. 10, 1982, 1833 U.N.T.S. 3, 21 I.L.M. 1261, entered into force Nov. 1, 1994.

- UNCLOS allocates a number of rights and responsibilities regarding “ships” and “vessels,” but does not define either term. Notably, the United States is not a party to UNCLOS, but asserts that the navigation and overflight provisions of the Convention are reflective of customary international law and that the United States therefore operates in conformity with those provisions. See Ronald Reagan, Statement by the President, 19 WEEKLY COMP. PRES. DOC. 383 (Mar. 10, 1983); U.S. Oceans Policy, 83 DEP’T STATE BULL., June 1983, at 70, 22 I.L.M. 464 (1983).

- COLREGS or “Rules of the Road”68: Generally, the COLREGS consist of two sets of rules: (1) the International Rules and (2) the Inland Rules:

- Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea, Oct. 20, 1972, T.I.A.S. 8587, 28 U.S.T. 3459 (COLREGS); Amendments to 72 COLREGS effective June 1,

__________________

68 Citations in this report and Appendix to the “COLREGS” are to the International Rules unless otherwise specified.

-

- 1983 (48 FR 28634). (“These [International] Rules shall apply to all vessels upon the high seas and in all waters connected therewith navigable by seagoing vessels.”)69

- Inland Navigation Rules, 33 C.F.R. § 83.03(q) (2017). (“Inland Waters means the navigable waters of the United States shoreward of the navigational demarcation lines dividing the high seas from harbors, rivers, and other inland waters of the United States and the waters of the Great Lakes on the United States side of the International Boundary.”)

Understanding that the ability of the UMV to intelligently maneuver through detection technology will drive much of any legal analysis on its applications, and thus the current case law70 on the COLREGS may be instructive in preparing relevant legal and policy memorandums:71

- Rule 2 (Good Seamanship and Special Circumstances) provides: “Nothing in these Rules shall exonerate any vessel … from the consequences of any neglect to comply with these Rules or of the neglect of any precaution which may be required by the ordinary practice of seaman” allowing for a “departure from these Rules necessary to avoid immediate danger.”72

- Yang-Tsze Ins. Ass’n v. Furness, Withy & Co., 215 F. 859 (2d Cir. 1914)

- Thurlow v. United States, 295 F. 905 (D. Mass. 1942)

- The Llanover [1945] 78 Lloyd’s List Lloyd’s Register (LR) 198 (Eng.)

- Rule 3 (General Definitions) provides: “the word ‘vessel’ includes every description of watercraft, including nondisplacement craft,

__________________

69 See https://www.navcen.uscg.gov/pdf/navRules/navrules.pdf.

70 Credit to the U.S. Navy Admiralty & Maritime Law Division (Code 11) and CDR Chris Swain, U.S. Navy, for this survey of COLREGS-related case law.

71 It is “an open question whether the COLREGS apply to UMSs, creating an uncertain regulatory environment for unmanned systems and manned vessels that encounter them.” Christopher C. Swain. 2018. Towards greater certainty for unmanned navigation, a recommended United States military perspective on application of the “Rules of the Road” to unmanned maritime systems. Georgetown Law Technology Review 3:119–161, at 123. For robust discussion on this issue, see, for example, Craig H. Allen. 2018. Determining the legal status of unmanned maritime vehicles: formalism vs functionalism. Journal of Maritime Law & Commerce 49:477–514; Natalie Klein. 2019. Maritime autonomous vehicles within the international law framework to enhance maritime security. International Law Studies 95:244–271; Daniel Vallejo. 2015. Electric currents: programming legal status into autonomous unmanned vehicles. Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law 47:405–428.

72 The incorporation of “good seamanship” through automated navigation into UMV may prove challenging.

-

wing-in ground craft and seaplanes, used or capable of being used as a means of transportation on water.”

- For a survey on relevant case law on the U.S. domestic maritime law concerning the definition and classification of “ships” and “vessels” in the context of “unmanned ships,” see the Maritime Law Association of the United States, Response of MLA to CMI Questionnaire re Unmanned Ships.73

- Rule 5 (Lookout)74 states: “[e]very vessel shall at all times maintain a proper look-out by sight and hearing as well as by all available means appropriate in the prevailing circumstances and conditions so as to make a full appraisal of the situation and risk of collision.”

- The Ottawa, 70 U.S. (3 Wall.) 268 (1865)

- The Ariadne, 80 U.S. (13 Wall.) 475 (1871)

- The Tokio Marine & Fire Ins. Co., Ltd. v. Flora MV, No. CIV. A. 97–1154, 1999 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 267 (E.D. La. 1999), aff’d, 235 F.3d 963 (5th Cir. 2001)

- The Manchioneal, 243 F. 801 (2d Cir. 1917)

- Mar. & Mercantile Int’l L.L.C. v. United States, No. 02-CV-1446, 2007 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 19792 (S.D.N.Y. Feb. 28, 2007)

- The Illinois, 103 U.S. 298 (1880)

- Ellis Towing & Transp. Co. v. Socony Mobil Oil Co., 292 F.2d 91 (5th Cir. 1961)

- Stevens v. United States Lines Co., 187 F.2d 670 (1st Cir. 1951)

- The Sarasota, 37 F. 119 (S.D.N.Y. 1888)

- In re Interstate Towing Co., 717 F.2d 752 (2d Cir. 1983)

- In re Ballard Shipping Co., 823 F. Supp. 68 (D.R.I. 1993)

- In re Delphinus Maritima, S.A., 523 F. Supp. 583 (S.D.N.Y. 1981)

- In re Flota Mercante Grancolombiana, S.A., 440 F. Supp. 704 (S.D.N.Y. 1977)

__________________

73 Response of MLA to CMI Questionnaire RE Unmanned Ships, at https://perma.cc/D6Z5-63UJ.

74 Applying Rule 5 directly to UMV operations may present the greatest legal obstacles. For example, some scholars have suggested that inclusion of the words “sight” and “hearing” indicate that observation is based on human characteristics, or that a “formal” approach should be applied to COLREGS treaty interpretation or amendment codified in the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. Others suggest pragmatic or “functional” approaches to COLREGS interpretation are appropriate and that legal risk can be justified if UMV can prove safe and prudent operations; in support, some opine that the IMO has not adopted a strictly literal interpretation of the Rule 5 requirements in the past, and it “is therefore possible that electronic instruments and equipment can replace the human function of observation, assuming that the technologies used are at least as effective and safe as diligent humans performing the lookout functions.” See European Maritime Safety Agency, “SAFEMASS Study of the Risks and Regulatory Issues of Specific Cases of MASS,” at http://www.emsa.europa.eu/emsa-documents/latest/item/3892safemass-study-of-the-risks-and-regulatory-issues-of-specific-cases-of-mass.html.

-

- Reading Co., Inc. v. Pope & Talbot, Inc., 192 F. Supp. 663 (E.D. Pa. 1961), aff’d, 295 F.2d 40 (3d Cir. 1961)

- United States v. Motor Ship Hoyanger, 265 F. Supp. 730 (W.D. Wash. 1967)

- The Bristol, 4. F. Cas. 159 (S.D.N.Y. 1873) (No. 1891)

- Cabins Tanker Indus., Inc. v. The Rio Maracana, 182 F. Supp. 811 (E.D. Va. 1960)

- The Bright, 38 F. Supp. 574 (D. Md. 1941)

- The Volund, 181 F. 643 (2d Cir. 1910)

- The Madiana, 63 F. Supp. 948 (S.D.N.Y. 1944)

- Commonwealth & Dominion Line v. United States, 1925 AMC 1575 (E.D.N.Y. 1925)

- Doran v. United States, 304 F. Supp. 1162 (D.P.R. 1969)

- Rule 6 (Safe Speed) states: “[e]very vessel shall at all times proceed at a safe speed so that she can take proper and effective control to avoid collision and be stopped within a distance appropriate to the prevailing circumstances and conditions.”

- Otal Invs. Ltd. v. M.V. Clary, 494 F.3d 40 (2d Cir. 2007)

- The Umbria, 166 U.S. 404 (1897)

- Union Oil Co. of California v. The San Jacinto, 409 U.S. 140 (1972)

- The George H. Jones, 27 F.2d 665 (2d Cir. 1928)

- Rule 7 (Risk of Collision) states: “Every vessel shall use all available means appropriate to the prevailing circumstances and conditions to determine if risk of collision exists….”

- In re Ocean Foods Boat Co., 692 F. Supp. 1253 (D. Or. 1988)

- Paterakis v. United States, 849 F. Supp. 1106 (E.D. Va. 1994)

- In re G&G Shipping Co., Ltd. of Anguilla, 767 F. Supp. 398 (D.P.R. 1991)

- Fireman’s Fund Ins. Cos. v. Big Blue Fisheries, Inc., 143 F.3d 1172 (9th Cir. 1998)

- Ching Sheng Fishery Co., Ltd. v. United States, 124 F.3d 152 (2d Cir. 1997)

- Rule 8 (Action to Avoid Collision) states: “Any action taken to avoid collision shall be taken in accordance with the Rules of this Part and shall, if the circumstances of the case admit, be positive, made in ample time and with due regard to the observance of good seamanship….”

- In re Ocean Foods Boat Co., 692 F. Supp. 1253 (D. Or. 1988)

- In re G&G Shipping Co., Ltd. of Anguilla, 767 F. Supp. 398 (D.P.R. 1991)

- Mar. & Mercantile Int’l L.L.C. v. United States, No. 02-CV-1446, 2007 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 19792 (S.D.N.Y. Feb. 28, 2007)

-

Rule 19 (Conduct in Restricted Visibility) applies: “to vessels not in sight of one another when navigating in or near an area of restricted visibility….”

- Hellenic Lines, Ltd. v. Prudential Lines, Inc., 730 F.2d 159 (4th Cir. 1984)

Besides COLREGS, other international conventions simply use the term “ship” or “vessel” without purporting to define it. Table E-1 provides a summary of these definitions by Craig H. Allen.75

Domestic Legal Sources

Besides international law and conventions, the Coast Guard may rely on domestic statute, regulation, and policy in formulating determinations as to the legal status of a respective asset or platform.

For example, under U.S. statute, the word “vessel” includes every description of watercraft or other artificial contrivance used, or capable of being used, as a means of transportation on water. This definition does not distinguish between manned and unmanned watercraft (1 U.S.C. § 3).

And, while domestic operational authorities may vary from international counterparts, the application of emerging technologies to UMV present novel issues in admiralty law including those related to doctrines of seaworthiness, limitation of liability, and in rem liability.76 For admiralty incidents involving U.S. public vessels, including matters related to liability and waivers of sovereign immunity, the following statutes and case law if informative:

- Suits in Admiralty Act, 46 U.S.C. § 30901–30918 (2018)

- Public Vessels Act, 46 U.S.C. §§ 31101–31113 (2018)

- Canadian Aviator, Ltd. v. United States, 324 U.S. 215 (1945)

- The Pennsylvania, 86 U.S. 125, 1998 AMC 1506 (1873) (establishing the “Pennsylvania Rule”)

-

Lozman v. City of Riviera Beach, Florida, 133 S. Ct. 735, 2013 AMC 1 (2013).

- This is the leading U.S. case on determining “what is a vessel.” There, the U.S. Supreme Court held that a permanently moored

__________________

75 Craig H. Allen. 2018. Determining the legal status of unmanned maritime vehicles: formalism vs functionalism. Journal of Maritime Law & Commerce 49:477–514, Table 1.

76 See Michal Chwedczuk. 2016. Analysis of the legal status of unmanned commercial vessels in U.S. admiralty and maritime law. Journal of Maritime Law & Commerce 47(2):156–166. See also Christopher C. Swain. 2018. Towards greater certainty for unmanned navigation, a recommended United States military perspective on application of the “Rules of the Road” to unmanned maritime systems. Georgetown Law Technology Review 3:119–161, at 151–154.

TABLE E-1 “Ship” and “Vessel” Definitions by Various International Conventions

| Instrument | Definition |

|---|---|

| COLREGS | Rule 3(a): The word “vessel” includes every description of watercraft, including non-displacement craft Wing-In Ground craft, and seaplanes, used or capable of being used as means of transportation on water. |

| SOLAS | No single definition. See, e.g., Reg. I/3(a)(i)–(vi), Reg. V/2.3: “All ships” mean any ship, vessel or craft irrespective of type and purpose. |

| MARPOL | Art. 2(4): “Ship” means a vessel of any type whatsoever operating in the marine environment and includes hydrofoil boats, air-cushioned vehicles, submersibles, floating craft, and fixed or floating platforms. |

| UN Convention on Registration of Ships | Art. 2: “Ship” means any self-propelled sea-going vessel used in international seaborne trade for the transport of goods, passengers, or both with the exception of vessels of less than 500 gross registered tons. |

| London Dumping Convention | Art. III(2): “Vessels and aircraft” means waterborne or airborne craft of any type whatsoever. This expression includes air cushioned craft and floating craft, whether self-propelled or not. |

| Hague Convention | Art. 1(d): “Ship” means any vessel used for the carriage of goods by sea. |

| SALCON 1989 | Art. 1(b): “Vessel” means any ship or craft, or any structure capable of navigation. |

| CLC Convention (and Fund Convention) | Art. I1: “Ship” means any sea-going vessel and any seaborne craft of any type whatsoever actually carrying oil in bulk as cargo. |

| OPRC Convention | Art. 2(3): “Ship” means a vessel of any type whatsoever operating in the marine environment and includes hydrofoil boats, air-cushion vehicles, submersibles, and floating craft of any type. |

| SUA Convention | Art. 1: “Ship” means a vessel of any type whatsoever not permanently attached to the sea-bed, including dynamically supported craft, submersibles, or any other floating craft. |

| Lisboa Rules (not a treaty) | “Vessel” means any ship, craft, machine, rig, or platform whether capable or navigation or not, which is involved in a collision. |

SOURCE: Craig H. Allen. 2018. Determining the legal status of unmanned maritime vehicles: Formalism vs functionalism. Journal of Maritime Law & Commerce 49:477–514, Table 1.

-

- houseboat was not a vessel because “a reasonable observer, looking to the home’s physical characteristics and activities, would not consider it to be designed to any practical degree for carrying people or things on water.” The Court opined that the 1 U.S.C. § 3 definition of “vessel” must be applied in a practical, not a theoretical way.

- Evansville & Bowling Green Packet C. v. Chero Cola Bottling Co., 271 U.S. 19, 22 (modifying interpretation of 1 U.S.C. § 3 by determining that the word “capable” should be read “practically capable”).

- Stewart v. Dutra Constr. Co., 543 U.S. 481, 2005 A.M.C. 609 (2005) (adopting the statutory definition of “vessel” set out at 1 U.S.C. § 3 without limit as to the size or purpose of the vessel).

- The Robert W. Parsons, 191 U.S. 17, 2010 A.M.C. 542 (1903) (suggesting the basic criterion used to decide whether a structure is a vessel is the purpose for which it is constructed and the business in which it is engaged).

Coast Guard Legal Interpretations

The issue of “what is a vessel” is not a novel matter for the Coast Guard. In fact, in its Legal Determination on Vessel Status of Paddleboard (Oct. 3, 2003), the Coast Guard Boating Safety Division (CG-5422) promulgated a determination on whether the Coast Guard considers a “paddleboard” to be a vessel. In that determination, the Coast Guard established a five-pronged test for determining whether any given watercraft is capable of being classified as a “vessel,” provided here in relevant part:

- Whether the watercraft is “practically capable” of carrying persons or property,

- Whether the useful operating range of the device is limited by the physical endurance of its operator,

- Whether the device presents a substantial hazard to navigation or safety not already present,

- Whether the normal objectives sought to be accomplished by the regulation of a device as a “vessel” are present, and

- Whether the operator and/or cargo would no longer be safe in the water if the device became disabled.

As the Coast Guard acknowledged in that determination, the criteria outlined above will not be applicable to every watercraft for which there

is a question of status, and there is no set formula for making vessel determinations—each determination must be made on an individual basis.77

U.S. DOD Navy Legal Interpretations and Guidance

The U.S. Navy has also promulgated guidance on which the Coast Guard can rely in evaluating legal status of UMVs, for example:

- U.S. Navy, Marine Corps & Coast Guard, Commander’s Handbook on the Law of Naval Operations, NWP 1-14M/MCTP 11-10B/COMDTPUB P5800.7A (2017)

- DoD Directive 3000.09 (2012) (Change 1, May 8, 2017), Autonomy in Weapon Systems78

The Navy has also granted exemptions from regulatory and certification requirements for certain unmanned surface vehicles under 33 U.S.C. 1605 (Navy and Coast Guard vessels of special construction or purpose).

- Specifically, the Navy has “certified that Unmanned Surface Vehicles with hull numbers 11MUC0601, 11MUC0602, 11MUC0603 and 11MUCO604 are vessels of the Navy which, due to their special construction and purpose, cannot fully comply with the following specific provisions of 72 COLREGS without interfering with its special function as a naval ship.” See 32 C.F.R. § 706.2; 73 FR 200 (Oct. 15, 2008), 60947–60948.

- E.O. 11964 of January 19, 1977, Implementation of the Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea, 1972

- With respect to the number, positions, range, or arc of visibility of lights or shapes required of the 1972 COLREGS, this E.O. provides that the “Secretary of the Department in which the Coast Guard is operating is authorized, to the extent permitted by law, to promulgate such rules and regulations that are necessary to implement the provisions of the Convention and International Regulations.”

__________________

77 See https://homeport.uscg.mil/Lists/Content/Attachments/537/Ahmanson%20Attachments.PDF.

Best Practices

The Coast Guard Navigation Safety Advisory Council (NAVSAC)79 has published “Unmanned Vehicles/Vessels” (2011) (Resolution 11-02) and “Unmanned Maritime Systems Best Practices” (Resolution 16-01):

- NAVSAC (Resolution 11-02) made recommendations that the U.S. Coast Guard sponsor amendments to both the Inland Rules and COLREGs that, among other measures, amends Rule 5 to exclude unmanned surface vessels from the look-out requirement by adding “manned” before “vessel,” and to “promulgate an interpretive rule under 33 C.F.R. Parts 82 and 90 to provide that a vessel being operated remotely is considered to be manned and must comply with the applicable Navigation Rules and annexes.”80

- NAVSAC (Resolution 16-01) provides guidance and information on “Unmanned Maritime Systems Best Practices” to UMS owners and operators on matters concerning UMS development and operations in the maritime environment.81

Maritime UK has also published the voluntary Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships (MASS) UK Industry Conduct Principles and Code of Practice, which provides practical guidance for the design, construction, and safe operation of autonomous and semi-autonomous MASS less than 24 meters (November 2019, ver. 3).82

LR Code for Unmanned Marine Systems (Feb. 2017) is a goal-based code that takes a structured approach to the assessment of unmanned marine systems (UMSs) against a set of safety and operational performance requirements.83

__________________

79 NAVSAC is a federal advisory committee authorized by Title 33 U.S.C. 2073 and chartered under the Federal Advisory Committee Act (Pub. L. 92-463; Title 5 U.S.C. App.).

80 See https://homeport.uscg.mil/Lists/Content/Attachments/726/NAVSAC%20-%20May%202011%20meeting%20-%20summary%20record.pdf. To date, these NAVSAC recommendations have not been adopted by the Coast Guard.

81 See https://maddenmaritime.files.wordpress.com/2016/06/navsac-resolution-16-01unmanned-maritime-systems-ums-best-practices-final-05-may-2016.pdf.

82 See https://www.maritimeuk.org/documents/478/code_of_practice_V3_2019_8Bshu5D.pdf. Notably, in 2017 the United Kingdom Ship Register signed its first “autonomous vessel,” the 7.2 meter C-Worker 7.

83 See https://www.lr.org/en/latest-news/new-code-to-certify-unmanned-vessels-announced; see also LR Cyber-enabled ships ShipRight procedure assignment for cyber descriptive notes for autonomous & remote access ships.

Current Regulatory and Collaborative Projects

Ongoing projects may provide useful guidance to the Coast Guard on UMV.

Domestic84

- Coast Guard Request for Information on Integration of Automated and Autonomous Commercial Vessels and Vessel Technologies into the Maritime Transportation System, Docket No. USCG-2019-0698 (85 Fed. Reg. 48548, Aug. 11, 2020)85

- E.O. 13859, Maintaining American Leadership in Artificial Intelligence, 84 Fed. Reg. 3967 (14 Feb. 2019)86

- U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) Automated Vehicles Activities, Ensuring American Leadership in Automated Vehicle Technologies: Automated Vehicles 4.0 (AV 4.0)87

- Maritime Administration (MARAD)88

- U.S. Committee on the Marine Transportation System89

- The Smart Ships Coalition of the Great Lakes-Saint Lawrence90

- SUNY Maritime College Maritime Global Technologies Innovation Center91

- Ship Operations Cooperative Program U.S. Maritime Autonomous Vessel Consortium92

- Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International, Unmanned Maritime Systems (UMS) Advocacy Committee93

__________________

84 The Coast Guard is an active participant in many of these groups.

85 See https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-08-11/pdf/2020-17496.pdf.

86 See https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2019-02-14/pdf/2019-02544.pdf.

87 See https://www.transportation.gov/av/4; see also Federal Register Notice, DOT-OST-2019-0179 (USDOT and the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy [OSTP] inviting public comment on AV 4.0).

88 See, for example, Achieving Critical MASS conference (July 2019), at https://www.maritime.dot.gov/about-us/foia/presentations-achieving-critical-mass-conference-july-2019.

89 See https://www.cmts.gov/topics.

90 See https://smartshipscoalition.org. In January 2018, the Coast Guard was briefed on the concept of operations for a Great Lakes autonomous vessel testbed and received a draft plan from the Michigan Office of the Great Lakes and the Great Lakes Research Center detailing the potential test area, the types of testing it could support, and requirements for operation and risk mitigation. The assumption is that operation of autonomous surface vessels and vehicles and autonomous underwater vehicles in the Marine Autonomy Research Site will still be subject to USCG regulations that involve the state of maneuverability, commonly accepted Rules of the Road and other requirements.

91 See https://www.nymic.org.

92 See http://www.socp.us/article.html?aid=106.