Applying Procedural Justice to Sexual Harassment Policies, Processes, and Practice: Issue Paper (2022)

Chapter: Applying Procedural Justice to Sexual Harassment Policies, Processes, and Practice

![]() PERSPECTIVES

PERSPECTIVES

Applying Procedural Justice to Sexual Harassment Policies, Processes, and Practice

Edited by Elizabeth Umphress and Jeena M. Thomas Authored by members of the Prevention Working Group of the Action Collaborative on Preventing Sexual Harassment in Higher Education1

This Perspective Paper is a product of the National Academies’ Action Collaborative on Preventing Sexual Harassment in Higher Education, which identifies and discusses a topic that is in need of research. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily of the authors’ organizations or the Action Collaborative on Preventing Sexual Harassment in Higher Education. They do not represent formal consensus positions of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Copyright by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.

Learn more: www.nationalacademies.org/sexualharassmentcollaborative

__________________

1 Information about the authors can be found at the end of the paper.

A 2018 report of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Sexual Harassment of Women: Climate, Culture, and Consequences in Academic Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, identifies the significant negative consequences of sexual harassment in higher education and provides recommendations for reducing and preventing its occurrence. Based on that report and additional research, sexual harassment includes sexual coercion (i.e., making organizational outcomes contingent on sexual cooperation); unwanted sexual attention (i.e., unwelcomed sexual advances, such as unwanted touching, stroking, and requests for dates; also including sexual assault); and gender harassment (i.e., hostile, objectifying, exclusive, degrading, insulting, or demeaning verbal or nonverbal behaviors directed to one gender) (Fitzgerald et al., 1995; Holland and Cortina, 2013; NASEM, 2018). Those who have experienced sexual harassment are subject to a variety of negative outcomes, ranging from reduced psychological well-being (e.g., higher levels of depression, stress, and anxiety) to negative workplace outcomes (e.g., higher levels of burnout, decreased performance and organizational commitment, turnover) (NASEM, 2018). Those negative outcomes can have cascading effects on groups, departments, and organizations within the institution by increasing legal costs, turnover, and absences, and reducing productivity, creativity, and representation of women and marginalized groups (Shaw et al., 2018).

The 2018 National Academies report recommends the creation of institutional policies that can improve an institution’s climate, culture, and reporting options while supporting those who have experienced sexual harassment. Creating and revising policies so that they are clear and comprehensive and promote a climate within an institution in which sexual harassment is not tolerated has the potential to protect those affected by sexual harassment and prevent future incidents (McDonald, 2012). Evidence from psychological and organizational literature over the past 40 years shows that employees’ perceptions of procedural justice strongly predict individually and organizationally relevant outcomes (Colquitt et al., 2013; Rupp et al., 2017; Thibaut and Walker, 1975). This perspective paper addresses the 2018 report recommendations by exploring how a procedural justice framework could help guide improvements and revisions to policies, processes, and practices within higher education institutions with the potential to mitigate the negative experiences and outcomes of those affected by sexual harassment. Based on previous research, this paper applies a principles-based perspective to highlight ideals, rules, and standards that institutions can implement to achieve this goal.

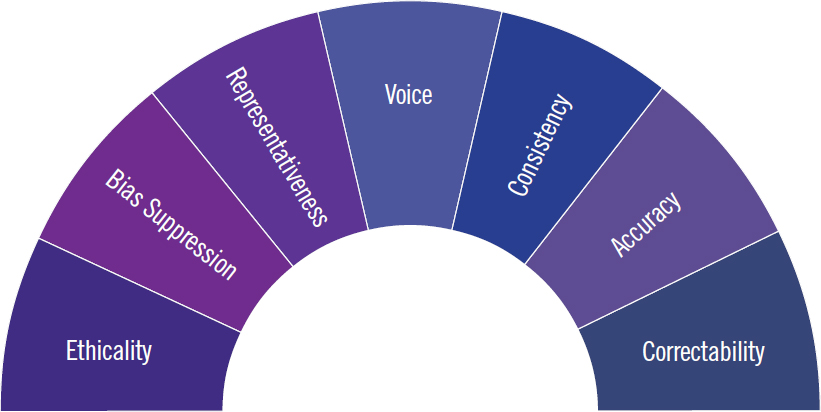

This paper continues by explaining the concept of procedural justice, the seven principles on which it rests, and its importance in combating the pernicious effects of sexual harassment in institutions of higher education. The paper then examines each of these principles and its application in turn. An appendix outlines questions institutions can ask when considering how to implement the principles in sexual harassment policies, processes, and practices. Definitions used in this paper are defined in Box 1.

THE CONCEPT AND IMPORTANCE OF PROCEDURAL JUSTICE

Procedural justice is the level of fairness individuals perceive when considering how outcomes of a particular decision are made (Folger and Greenberg, 1985). The first discussion of procedural justice by Thibaut and Walker (1975) grew out of insights gained from adjudications, mediations, and arbitrations in which disputants were sometimes equally if not more concerned with the processes that led to outcomes than with the outcomes themselves. Higher levels of procedural justice are perceived when processes for reaching decisions and outcomes are seen as fair because the institution strives to follow all seven of the following principles (Leventhal, 1980; Thibaut and Walker, 1975):

BOX 1

Definitions

Parties Identified in This Paper

- Those who have experienced sexual harassment: Individuals who self-identify as having experienced sexual harassment, regardless of whether they have been involved in a formal reporting process, or have had an experience of sexual harassment confirmed by an investigation. This term also applies to those who may also identify as “targets,” “victims,” or “survivors.”

- Those who have reported experiencing sexual harassment: Individuals who file a sexual harassment report with a higher education institution and may or may not proceed with a formal investigation process. The term can encompass someone before, during, or after an investigation.

- Those who are accused of sexual harassment: Individuals who are formally accused of sexual harassment (i.e., once a report has been filed, and either before, during, or after an investigation has occurred).

- Those who have committed sexual harassment: Individuals who are found responsible for having committed sexual harassment through a formal investigation process, or who self-identify as having perpetrated sexually harassing behaviors.

- Observers: Individuals who witness or are aware of sexual harassment occurring but are not directly involved (e.g., witnesses; those in the same community and/or spheres of influence in which the harassment occurred; colleagues, friends, superiors, subordinates, alumni, and/or those outside the institution).

- Those affected by sexual harassment: Individuals in the broader community, including those who have experienced or reported experiencing sexual harassment, those who are accused of sexual harassment, those who have committed sexual harassment, and observers.

Definitions of Policy, Process, and Practice

- Policy: An institution’s formal, written rule(s) that define and prohibit sexual harassment. Those who draft and/or revise such institutional policies are referred to as policy makers.

- Process: The formal, written implementation steps for a policy. In the case of a sexual harassment policy, the process involves the procedural steps that can be taken, such as (1) reporting a potential violation of the policy, (2) determining whether a violation of the policy has occurred, and (3) deciding when a violation is or is not found. Those who draft and/or revise such institutional processes are referred to as process makers.

- Practice: The informal actions, traditions, norms, and understandings within units/departments/organizations at a higher education institution.

- Ethicality—being consistent with the prevailing ethical standards within society

- Bias suppression2—removing bias or prejudice from a policy, process, or practice

- Representativeness—including the interests of all affected parties

- Voice—expressing the opinions of those affected before, during, and/or after a decision-making process

__________________

2 For the purpose of this paper, we use the term “bias suppression” for consistency with the language used in the procedural justice literature.

- Consistency—applying policies consistently across people and time

- Accuracy—using valid and precise information to make decisions

- Correctability—adjusting policies, processes, and practices so that they are informed by outcomes

Adherence to all seven principles is important, as the principles are highly interrelated, and one cannot be implemented successfully without the others (see Figure 1). As one could imagine, lower levels of procedural justice occur when one or more of the principles above are not followed (Colquitt, 2001).

Research on procedural justice has been conducted mainly in business settings—for example, in evaluating the perceived fairness of practices in strategic planning (Kim and Mauborgne, 1993), selection and reward systems (e.g., McFarlin and Sweeney, 1992), conflict management (e.g., Goldman, 2003), and layoff decisions (e.g., Brockner et al., 1994). While procedural justice has not yet been applied as a tool for measuring and interpreting changes in organizational climate (e.g., determining if such changes reflect a decrease in conflict), it has been shown to be positively related to such outcomes as organizational commitment, trust in one’s supervisor and organization, perceived supervisor support, job performance, and extra-role or discretionary positive behavior aimed at helping the supervisor or organization (Colquitt et al., 2013). Likewise, outcomes that organizations wish to minimize, such as counterproductive work behavior (Colquitt et al., 2013), stress (Judge and Colquitt, 2004), and depression (Spell and Arnold, 2007), have been shown to decrease in environments that accord with the principles of procedural justice. Procedural justice also affects the outcomes of observers who have exhibited negative psychological responses and behaviors upon viewing someone else being treated in a procedurally unfair manner (Skarlicki and Kulik, 2005).

The principles of procedural justice can be applied to such factors as power differentials, intersectionality of identities, and privilege, each of which influences perceptions of fairness.3 Procedural justice principles can be applied, for example, to bias suppression, representativeness, and the use of voice in decision making. Bias suppression involves actively reducing in-group and dominant-group bias that may occur when decisions are made (Bazerman and Tenbrunsel, 2012; Devine et al., 2012). Representativeness requires consideration of who is involved in making decisions and who has the power to make decisions (Leventhal, 1980). It ensures the inclusion of individuals from the different groups affected by decisions and acknowledges their intersectionality and privilege. Voice includes granting to those who will be impacted by decisions the opportunity to be heard (Tyler, 1990), helping to increase their power and impact and ensuring that their experiences and perspectives are valued.

We believe that incorporating the procedural justice principles outlined above can make sexual harassment policies, processes, and practices fairer for those affected by sexual harassment and create greater trust in related decision-making processes in higher education. Knowing that the procedural justice literature is focused on business settings, this paper considers how the application of these principles might look in higher education. It is our hope

__________________

3 We define these terms as follows:

- Power differentials—The positional authority and identity that results in power, where there is potential for individuals and/or institutions to have more or less influence or control over a situation and valued resources based on their position, title, gender, race, level of authority, etc. (Magee and Galinsky, 2008).

- Intersectionality—A lens for understanding how social identities (e.g., race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, age, and disability status), especially for marginalized groups, relate to systems of authority and power (Crenshaw, 1989; NASEM, 2021).

- Privilege—Increased favorability or an advantage for a particular party over another based on the amount of power held and the social identities observed that results in unearned advantage, entitlement, or privilege (e.g., male privilege, White privilege). Often, privilege operates by remaining invisible to those individuals/groups that are its beneficiaries (Privilege, 2021).

that in so doing, the paper will highlight the benefits of procedural justice (e.g., increased organizational commitment, increased trust in supervisors and the organization) in higher education, which in turn can lead to an improved organizational climate that results in better prevention of sexual harassment.

This paper focuses on the formative procedural justice research completed by Drs. Leventhal (1980) and Thibaut and Walker (1975), upon which later research (e.g., Bazerman, Colquitt, Folger, Greenberg, and Tenbrunsel) builds. Although the principles of procedural justice could apply to many aspects of higher education, such as decision-making processes related to faculty hiring or the allocation of research funds, the goal of this paper is to examine how they could be applied to optimize sexual harassment policies, processes, and practices. Recognizing that these principles have yet to be applied directly to those policies, processes, and practices, our aim is to (1) identify policies, processes, and practices focused on the goal of preventing sexual harassment in varying environments, organizations, and higher education institutions; (2) inspire relevant stakeholders to consider these foundational principles when constructing such policies; and (3) prompt further inquiry and research on policies that can create a climate conducive to achieving this goal.

When applying the principles of procedural justice, we also find it important to do so through an equity lens,4 whereby a decision is based on individuals’ needs or access to resources. Applying this lens means highlighting how the principles apply when some groups have historically not been included or have been only minimally included, and then working to address that inequity. In the case of sexual harassment policies, processes, and practices, three groups that historically have not been included are those who have experienced sexual harassment, those who are from traditionally marginalized groups (Code, 1995; Eyre, 2000; Peirce et al., 1998), and those with vulnerabilities caused by power differentials (Fitzgerald, 2021). Conversely, those who are accused of and/or have committed sexual harassment and those from nonmarginalized groups (typically White, upper-class,

__________________

4 There are at least two different ways for determining the fair allocation of outcomes: equality and equity (see, e.g., Leventhal, 1976). The authors of this paper define equality as distributing an outcome equally to individuals without regard to their specific needs or access to resources, while equity refers to distributing an outcome with regard to individuals’ specific needs and access to resources. This paper looks at procedural justice fairness through the lens of increasing equity.

men-identifying) have historically been included or have been in positions of authority that have made them responsible for the development and revision of sexual harassment policies, processes, and practices. Such factors as bias and power differentials have led institutions to minimize or deny harassment offenses, protecting the harasser and blaming the victim (Peirce et al., 1998). These inequities directly affect how such procedural justice principles as representativeness and voice are applied to sexual harassment in higher education. Ultimately, procedural justice principles should lead to policies, procedures, and practices that fairly involve all people impacted by sexual harassment, including those who have experienced such harassment and those who are accused of and/or have committed it. In this paper, the focus is on the application of procedural justice principles to individuals who have experienced sexual harassment, with special attention to those subject to historical inequities.

We recognize that institutions seeking to apply procedural justice principles may encounter substantial hurdles, especially when faced with budget constraints, varied stakeholder groups, and other institutional realities. While the purpose of this paper is to describe an ideal toward which institutions can strive, the sections below discussing each principle in turn also highlight institutional examples, address challenges (e.g., staff burden, time constraints) when feasible, and propose ideas for readers to consider. The latter purpose is served by a box at the end of each section that poses questions for institutions to consider in applying the respective principle. A box at the end of the paper suggests research questions that need to be explored to address gaps in the procedural justice research related to sexual harassment and institutional challenges that may hinder the application of the procedural justice principles. All of these questions are collected together in the appendix at the end of the paper.

ETHICALITY

The other six principles of procedural justice, especially as they relate to addressing sexual harassment, should all be grounded in the principle of ethicality, according to which policies and practices adhere to the standards of morality within society (Leventhal, 1980). Ethicality can also be understood by adopting Kant’s (1992) universal principle of caring for others (see also Haidt, 2012). Care is defined in turn as the demonstration of concern for others’ pain and suffering, and is consistent with notions of kindness and goodwill (Haidt, 2012). Applying care, and therefore ethicality, to sexual harassment in higher education requires seeing all individuals involved—including those who have reported experiencing sexual harassment, those who have been accused of sexual harassment, those who have experienced sexual harassment, those who have committed sexual harassment, and those who have observed sexual harassment—as complete persons. Inadequate recognition of individuals and their identities is akin to the “splitting of a whole person,” which in turn can cause harm and oppression (Gruenfeld et al., 2008).

How to Apply Ethicality

Institutions can implement the principle of ethicality by prioritizing care when creating and revising sexual harassment policies and practices. Doing so entails having a deliberate plan in policy making to (1) treat all those involved with respect and dignity (Bies and Moag, 1986), (2) acknowledge the fundamental rights of individuals as human beings, (3) recognize that all individuals are unique and have different preferences as to how they want to engage with institutional processes related to sexual harassment, and (4) minimize further harm to those involved in the process (Haidt, 2012). One way in which policy and process makers could demonstrate ethicality is through “perspective taking,” or actively

imagining the psychological perspective of another person, which increases empathy (Batson et al., 1997), decreases stereotyping and in-group favoritism (Galinsky and Moskowitz, 2000), decreases expressions of racial bias, and encourages individuals to make favorable assessments of those of other races (Todd et al., 2011). Policy and process makers in higher education institutions do not lack empathy, but various confounding factors (e.g., stereotypes, biases, or having empathy for those on both sides affected by sexual harassment) can result in harassers receiving no punishment or “not guilty” verdicts (Galinksy and Moskowitz, 2000).

To mitigate the influence of factors that may make it challenging to incorporate ethicality in decision making, policy and process makers can actively engage in activities, such as perspective taking (Galinsky and Moskowitz, 2000), that are known to increase empathetic responses. In practice, these activities might include the following:

- Policy and process makers imagining themselves or a loved one in the situation of having experienced, reported, been accused of, committed, or observed sexual harassment.

- Institutions of higher education providing policy and process makers with opportunities for training and discussion on the meaning of ethicality.

- Policy and process makers regularly evaluating each existing or new policy (and related processes) on sexual harassment for its ethicality, asking themselves how ethicality is reflected in each policy.

- Institutions of higher education explicitly and publicly talking about ethicality as a priority in sexual harassment policy making. To name a few, the University of Iowa (2021), the University of Michigan (2021), and the University of Virginia (2021) are institutions that provide examples of publicly stating the role of ethicality (e.g., care, respect, dignity) in preventing sexual harassment.

Questions for Institutions to Consider When Applying Ethicality

- How can we change existing sexual harassment policies and procedures to acknowledge and respect the various identities that individuals embody?

- How can we augment existing sexual harassment procedures to ensure that those involved are treated with respect and dignity?

- How can we ensure that those involved in investigations are well supported and cared for once a case has been closed—for example, through remediation policies, processes, and practices?

- What policies, processes, and practices would individuals want in place for themselves or others to ensure that they are treated with respect and dignity?

- How can we ensure that respect and dignity is demonstrated to those involved in sexual harassment investigations while taking power differentials, intersectionality, and privilege into account?

BIAS SUPPRESSION

The principle of bias suppression refers to preventing the inclination toward prejudice, whether positive or negative, in decision making when developing policies and processes; in the context of this paper, the procedural justice framework needs to be applied when bias negatively and systematically impacts one group or individual versus another. Suppressing bias requires establishing mechanisms for identifying implicit (unconscious) and explicit (conscious) bias and mitigating their possible harmful effects (Devine et al., 2012). When bias pervades human decision making, decisions become

corrupted by self-interest, loyalty, and misleading preconceptions of people and events (Bazerman and Tenbrunsel, 2012). Although many types of bias can permeate sexual harassment policies, processes, and practices, this paper focuses on (1) greater weight being given to those higher in authority/status and (2) conflicts of interest or situations in which a person has a personal or professional stake in the outcome of a decision.

How to Apply Bias Suppression

Status and Bias Suppression

Research demonstrates that individuals tend to pay more attention and give more weight to those with higher status or authority (Cialdini, 2001). Status and authority can be manifested in several ways, such as higher rank, advanced education, tenure status, greater prestige, or belonging to dominant groups within society (based on gender, race/ethnicity, position, and other salient identities; Lee and Tiedens, 2001). The tendency to give more attention and weight to individuals perceived as having higher status can influence investigators and decision makers involved in dealing with sexual harassment. Specifically, individuals at institutions may (1) pay more attention to reports of sexual harassment made by those with higher status (Ridgeway and Berger, 1986), (2) view reports of those with lower status as less believable (Belmi et al., 2020), and (3) more easily record and recall information in reports made by those with higher status (Magee and Galinsky, 2008).

Institutions could consider taking measures to recognize and address biases of investigators and decision makers involved in sexual harassment cases, bringing to light the role of these biases in policy making. The following are some examples of strategies that might serve this purpose:

- Ensuring that investigators and decision makers expend equal effort and care in discussing the reports of those with higher and lower status.

- Using systematic, standardized processes to record reports and events from each individual, regardless of status, to prevent biases of investigators from influencing those processes.

- Raising awareness of the biases of investigators and decision makers through education and discussion.

- Collecting objective data to assess bias (Banaji et al., 2003), such as by analyzing whether outcomes of sexual harassment investigations can be correlated with the rank, education level, tenure status, and/or race/ethnicity of (1) those who have reported experiencing sexual harassment and (2) those who are accused of sexual harassment.

Conflicts of Interest and Bias Suppression

Research on bias suppression suggests that most individuals believe they are not influenced by conflicts of interest. Evidence suggests, however, that this is not the case (Bazerman and Tenbrunsel, 2012); rather, those with a conflict of interest are likely to be biased but at the same time not to recognize that this bias exists. Given that conflicts of interest can be unconscious and can manifest in both public and private judgments (Moore et al., 2010), the best course of action is to remove conflicts of interest whenever possible. Yet this is not always a feasible solution, especially within smaller institutions. Institutions can account for barriers to the management of conflicts of interest by requiring that individuals who would be influenced or most influenced by a sexual harassment finding recuse themselves from any investigative or decision-making role in a sexual harassment case. Similarly, institutions can select individuals least affected by conflicts of interest to participate in the investigation or decision-making responsibilities related to a case. Institutions also can consider making use of third-party bodies that can keep biases stemming from conflicts of interest from influencing a case.

Conflicts of interest relevant to sexual harassment at institutions of higher education may affect the following individuals:

- Those appointed to or employed in the same unit as the individual who has reported experiencing sexual harassment and/or the individual who has been accused of sexual harassment. Depending on the size of an institution, a unit may be defined as the department/office, college, or other relevant organizational unit.

- Employees of internal institutional bodies who may have a significant conflict of interest because their work in managing sexual harassment may significantly overlap with a case (Chugh et al., 2005; Schreiber and Creswell, 2017). To help remove this potential conflict of interest, institutions can consider having a third party (an organization or person outside of the institution or ombuds office) investigate the case and determine the outcome (Dobbin and Kalev, 2020). Institutions can also consider using an outside investigator and outside adjudicator, such as a retired judge, to handle investigations and determine their outcomes (Grinnell College, 2020).

- Those with a personal/professional relationship with the individual who has experienced sexual harassment and/or the individual who has been accused of sexual harassment. For example, a leader in a higher education institution whose job it is to raise funds for a unit within the institution would not be involved in the investigation or report of a potential donor accused of sexually harassing an employee of the institution. A conflict of interest would exist in this instance because the leader might value the donor’s funds, and be influenced accordingly in making a decision about the case. One potential strategy for such situations is providing parties to a sexual harassment investigation the names of potential investigators or those who might have a decision-making role in the investigation. The parties then can identify any conflicts they see among the names on that list. Similarly, potential investigators or those in decision-making roles can disclose conflicts of interest they may have to a Title IX coordinator and potentially remove themselves from the investigation.

Questions for Institutions to Consider When Applying Bias Suppression

- How can we avoid bias when creating and revising sexual harassment policies, processes, and practices?

- How do we prevent incidents of bias from occurring such that all parties are respected and treated fairly during a sexual harassment investigation?

- What strategies can we implement to further mitigate bias in future sexual harassment investigations?

REPRESENTATIVENESS

Under the principle of representativeness, those who have been or will be affected by a decision or incident are involved in related policy making (Leventhal, 1980; Tyler, 1988). As representation increases, power and control are shared more equitably in the decision-making process, leading to increased perceptions of fairness (Leventhal, 1980). Implementing representativeness requires careful attention to creating an inclusive climate that is mindful of historical inequities in policy and decision making so everyone involved can speak freely, voiced opinions are not subject to judgment, and safeguards against retaliation exist (see also section on voice below). Applying this principle to sexual harassment, representativeness means allowing those who have been or will be affected by sexual

harassment to be involved in making and revising related policies, processes, and practices. Sexual harassment has differing effects on individuals who vary in gender, sexuality, race, socioeconomic status, social location, rank, power, and role within an organization (Fitzgerald and Cortina, 2018). Including individuals from these different groups in policy making related to sexual harassment makes it possible to better understand, react to, reflect, and incorporate these varying perspectives. Representing the range of individuals impacted by sexual harassment aids in addressing and preventing sexual harassment more effectively and can also help with restorative justice efforts for the community once a case has been closed.

How to Apply Representativeness

Who Is Represented?

As noted above, the application of representativeness requires ensuring that individuals or groups representing those affected by sexual harassment are involved in making and revising sexual harassment policies, processes, and practices. It is also important to recognize historical inequities when applying representativeness by considering what groups have been better and less well represented because of power differentials and bias. As discussed previously, those from nonmarginalized groups and those in positions of authority have typically been represented in policy and process making; the result has sometimes been policies that are poorly written or vague or may lead to organizational inaction (Peirce et al., 1998). Meanwhile, marginalized groups and individuals who have experienced sexual harassment are often silenced (Eyre, 2000). It is not always clear which individuals or groups have been affected. When sexual harassment occurs publicly, for example, which is not uncommon in cases of gender harassment, many observers can be affected (NASEM, 2018), and many individuals will therefore need to be represented. As a baseline, institutions might consider representatives from such groups as the following when making and revising sexual harassment policies, processes, and practices:

- Those who have experienced sexual harassment and/or filed a sexual harassment report.

- Those who are demographically most likely to experience sexual harassment, with consideration of the intersectionalities of identities and different social groups.

- Those who represent grassroots nonprofit organizations and advocacy groups.

- Sexual harassment researchers and those familiar with the research on sexual harassment in higher education institutions.

- Those who provide support to individuals affected by sexual harassment.

- Those who provide support to institutions developing policies, processes, and practices related to sexual harassment—for example, faculty and staff.

- Those who directly observe the negative outcomes of sexual harassment and/or a sexual harassment investigation (including observers and those subject to the resulting toxic climate of sexual harassment), those who are accused of sexual harassment, and those who have committed sexual harassment.

- Undergraduates, graduate students, and post-doctorates. The following are a few examples of how institutions have represented students in creating and revising sexual harassment policies:

- – The University of California, Santa Cruz (2020), developed the Beyond Compliance initiative, in which a committee included graduate students to help inform policies and practices by creating a guide that addresses and attempts to remediate the impacts of sexual violence/sexual harassment experienced by the graduate student community.

- – The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2019) developed the MindHandHeart

- – Yale University (2021b) created a group of undergraduate and professional students on sexual harassment and violence called the Graduate and Professional Student Title IX Advisory Board. This group provides advice to the Yale Title IX Steering Committee and perspective on such issues as campus culture and investigation processes.

Department Support Program, or MHH-DSP, which brings together students, staff, and faculty from more than 20 offices and the 31 academic departments to collaborate, connect, share, and develop plans to “measurably enhance their academic climates.”

Challenges to Applying Representativeness

When applying representativeness, it is important to consider such institutional barriers as the emotional (e.g., stress and trauma) and physical (e.g., time) demands associated with developing policies, processes, and practices around sexual harassment. Those who report sexual harassment, for example, may have experienced considerable trauma, and participating in policy making could potentially impose additional hardships (NASEM, 2018). Additionally, crafting policies and related processes for higher education institutions is time consuming. Although representation of students and junior faculty are important because they may be most vulnerable to sexual harassment as a result of their lower status in the institution (NASEM, 2018), they are also under tight time constraints to achieve scholarly goals as graduation or tenure. Thus, the goal of achieving representativeness needs to be balanced with the need to protect students and junior faculty from excessive service. Along the same lines, individuals with marginalized identities are more likely to take on invisible labor—work, such as time-consuming policy making, that does not necessarily bring attention to their personal scholarly profile work (Duncan, 2014; Fox, 2008; Griffin et al., 2011; Guarino and Borden, 2017; Hirshfield and Joseph, 2012). Accordingly, representation among those with marginalized identities could be accompanied by providing them with additional support (e.g., compensation; see below) and resources. In sum, representativeness is a necessary component of procedural justice, but institutions of higher education must remember that it exacts a larger toll on those affected by sexual harassment, those with lower status, and those who belong to traditionally marginalized groups.

An effort in the College of Literature, Science, and the Arts at the University of Michigan provides a specific example of an attempt to address representativeness while accounting for additional costs and burdens imposed on certain groups (see Box 2). Additionally, the following are a few potential strategies for addressing this tension:

- Distribute the workload equitably. The most time-consuming tasks associated with policy and process development can be taken on by individuals who are in positions (e.g., in the Provost’s Office, Human Resources, the Title IX Office, the Diversity & Equity Office) in which such labor is both expected and compensated. Institutions can devise creative ways of ensuring representativeness among other individuals—for example, through one-time, time-limited focus groups or interviews—without involving them in other aspects of policy and process making that may impose significant burdens in time, energy, and emotion.

- Recognize labor. Institutions can consider mechanisms by which such labor could be meaningfully recognized and rewarded—for example, recognition during employee annual reviews or in tenure and promotion materials.

- Make use of advocates. Institutions can rely on individuals who understand the perspectives of those who have experienced sexual harassment, those filing reports, and those in marginalized or low-status groups such that their values and concerns are represented without exacting a toll on their emotional resources and time.

BOX 2

Institutional Example: University of Michigan’s Effort to Address Representativeness

To create a climate that would help prevent sexual harassment, the College of Literature, Science, and the Arts at the University of Michigan undertook an effort focused on changing its policies and practices and implementing the recommendations of the 2018 National Academies report (NASEM, 2018). The initiative first required the formation of focus groups of tenured faculty, untenured faculty, staff, graduate students, and undergraduate student employees representing varied social identities (e.g., race, gender, sexual orientation). These focus groups provided input on what policies, processes, and practices needed to be changed in their different workspaces. Their time commitment was limited to 3 hours (including completion of background reading), and students were compensated for their participation. The focus groups were

- composed of individuals of the same role/rank/gender to reduce power differentials and increase openness in the discussion;

- facilitated by individuals from outside the university to reduce concerns about retaliation; and

- anonymous (i.e., focus group members’ names were erased from transcripts) to alleviate fears that comments would be attributed to any individual.

Input from the focus groups was then compiled by a working group. The working group did the bulk of the “heavy lifting” by

- compiling the input of the focus groups;

- creating an interim report;

- obtaining feedback on the interim report from key stakeholders and constituents (another way for different groups to be represented); and

- incorporating that feedback in a final report.

Importantly, to reduce the labor required of students and junior faculty, the working group consisted of an equal number of staff and tenured faculty. To ensure representation of students, the working group included staff members whose professional expertise centers on representing, advocating for, and understanding the concerns of graduate and undergraduate students. In all, this effort relied on lower-status groups to provide input, ideas, and feedback while assigning the time-consuming work to senior faculty and staff. The rationale behind this structure—to maximize representativeness and minimize labor for low-status and marginalized groups—was also clearly communicated to stakeholders.

- Provide compensation. Institutions can compensate marginalized and low-status individuals for their work on sexual harassment policy and process making. Junior faculty, for example, can be given a reduced course load for being involved in policy and process making work; graduate students can be given extra funding to support their research; undergraduate student employees, who are typically paid by the hour, can be compensated for their time; and staff can have

their regular workload adjusted by their supervisors to accommodate the effort associated with this work.

Questions for Institutions to Consider When Applying Representativeness

- How can we ensure representation of all necessary parties (including individuals who reported experiencing and those accused of sexual harassment) in the creation and revision of policies and processes around sexual harassment while accounting for labor burden?

- How can we ensure representation of those affected by sexual harassment such that we can create an inclusive climate when making policies and decisions, so all can speak freely, voiced opinions are not subject to judgment, and safeguards exist against retaliation?

- How can we represent all parties in policies, processes, and practices related to restorative justice efforts once a case has been closed or in other policies, processes, and practices that may help both prevent and remediate sexual harassment?

VOICE

Voice is the ability of interested parties to provide their opinion or outlook before, during, and/or after an outcome is determined (Tyler, 1990), outcome being defined as any salient output or consequence emanating from an authority (e.g., promotion, pay raise). For the purpose of this paper, salient outcomes might include, but are not limited to, developing of sexual harassment policy, initiating an investigation, or adjudicating an outcome. Granting voice in a process means not that those granted voice have a final say in the outcome, but that they are heard. Application of this principle requires careful attention to creating a culture in policy and process making whereby everyone involved (those who have experienced and/or reported sexual harassment, those accused of sexual harassment, and observers of sexual harassment) can be heard without judgment and is protected from retaliation.

As discussed in the section on representativeness above, for example, when an institution is revising a sexual harassment policy or process, it can seek input from various stakeholders via focus groups. Representativeness can be operationalized by ensuring that all relevant groups are invited to participate in the focus group sessions. Voice can then be incorporated not only by holding the focus group sessions but also by demonstrating that the institution has heard what was said during the sessions. Rutgers University (2019a) and Vanderbilt University (2019), for instance, provide opportunities for various stakeholders to engage in town halls, participate in informal focus groups, take part in councils that formulate recommendations, and participate in other opportunities for individuals to be heard. The act of “hearing” can be operationalized by summarizing—while maintaining discretion—what was shared in the focus group, and by reporting what will be done with the information moving forward and why. This follow-up explanation is important to demonstrate that the focus group results were not “filed away and forgotten”—a perception that has the potential to silence voice. The purpose of intentionally incorporating voice in making and revising sexual harassment policies and processes is to create an environment in which individuals can describe their experiences without judgment or retaliation, which in turn enables future reporting of sexual harassment.

Applying voice with an equity lens requires additional attention to those whose voices have historically

not been included. Perceptions of whether a complaint is heard without judgment or is taken seriously influence whether those who have experienced sexual harassment will report the experience to the institution (Peirce et al., 1997). Sexual harassment research suggests the importance of granting those who have experienced sexual harassment the opportunity not only to share their experiences but also to be heard in a nonjudgmental manner when expressing their concerns (Epstein, 2020; Kirkner et al., 2020). Thus, the principle of voice encompasses the equitable opportunity to be heard and have one’s concerns be considered by the institution without judgment or bias, thereby promoting trust and confidence among those affected by sexual harassment, especially those who have experienced it.

The ability to have a voice in the development and enactment of a policy or process has a strong effect on perceptions of procedural justice and fairness (Lind et al., 1990). Although voice at any point in a process is better than no opportunity for voice at all, procedural justice research shows that applying the principle of voice before rather than after a decision is made results in a greater perception of fairness in the final decision (Lind et al., 1990). Institutions therefore can consider incorporating voice well before a decision or investigation occurs, including when sexual harassment policies and processes are being developed. Doing so can result in both institutions and outcomes being viewed as more fair and effective and encourage those who have been affected by sexual harassment to disclose those incidents.

How to Apply Voice

Applying voice may be challenging in the face of various institutional barriers, such as budget and time limitations, given that added resources and coordination across many people may be required for institutions to demonstrate that they have heard the thoughts, perspectives, and experiences of others. Following are some strategies for and examples of efforts aimed at incorporating voice in policies, processes, and practices addressing sexual harassment.

Creating and Revising Policies, Processes, and Practices

Having voice in creating policies, processes, and practices addressing sexual harassment is common for some groups (such as a team of lawyers, the Office of Institutional Equity and the Office of the General Counsel), but it is uncommon for those who have historically been excluded (such as those who have reported and/or experienced sexual harassment and marginalized groups) (Dobbin and Kalev, 2020). Indeed, sexual harassment policies, procedures, and practices have led to a decline in employment of historically excluded groups (Dobbin and Kalev, 2020). This decline is especially evident in organizations with fewer women in managerial roles, which researchers suggest is because women are more likely than men to hear and believe reports of sexual harassment and, in turn, the voices of those historically excluded (Dobbin and Kalev, 2020). Institutions can equitably apply the principle of voice by taking steps to address the lack of access or opportunities for those who have historically been excluded or silenced, either intentionally or because of power differentials that lead to a fear of retaliation for speaking up. For instance, institutions can provide specific mechanisms for those who have experienced sexual harassment to share their perspective and proactively invite them to use these mechanisms to inform policy and process making. One such mechanism is having individuals affected by sexual harassment on committees or governing bodies that create sexual harassment policies. Other mechanisms for ensuring that these individuals have a safe space in which to share their voice can include conducting focus groups or anonymous surveys, or using representatives or advocates to speak on these individuals’ behalf.

Notification/Reporting and Investigation Process

The following examples illustrate how reporting and investigation policies and processes can facilitate voice for all those affected by sexual harassment (those who have committed and/or are accused of sexual harassment, as well as those who have reported and/or experienced sexual harassment):

- Informing those involved in the investigation of resources/support services—Voice can be facilitated and supported if all parties involved in a sexual harassment investigation are provided easy access early on to resources and support services available on campus and/or in the community. Examples include institutional support, such as academic accommodations, counseling services, health services, and housing accommodations; law enforcement/legal support; and community support, such as support groups and navigator programs.5

-

Provide the same opportunities for voice during an investigation—Those filing a sexual harassment report and those being accused both can participate in an investigation at multiple time points. For example, Purdue University (2021b) and Princeton University (2021) do the following for both of these individuals:

- – Provide advocates so that their voices are guaranteed to be heard and valued in the investigation process.

- – Offer them support services so that any expressed needs are met within available means.

- – Provide them both with same opportunities to give evidence and suggest possible witnesses for interview.

- – Allow them to review a draft of the investigator’s report.

- – Give them the opportunity to provide corrections and clarifications or a written response to the draft report.

The following are specific examples of strategies for addressing the historical inequities in voice for certain groups:

- Expanding options for reporting—Increasing flexibility and options for reporting or sharing their experience provides agency or choice for those who wish to report to their institution. Expanded options for reporting might include allowing individuals to decide how and when (if at all) their story will be shared moving forward, offering external reporting services, and providing confidential and/or anonymous reporting resources. An example of the latter is Callisto (2021), an online resource that allows multiple options for reporting a case. Offering such additional resources can help address power differentials and historical inequities whereby those who reported sexual harassment experienced retaliation and/or were blamed, were not believed, or saw the institution protect their harasser (Peirce et al., 1998)—actions that ultimately resulted in silencing many who experienced sexual harassment (Dobbin and Kalev, 2020; Peirce et al., 1997).

- Nonmandatory reporting—Institutions can consider designating nonmandatory reporters—individuals not required to file a complaint upon being informed of a sexual harassment incident, such as physicians, therapists, and faculty and staff not in leadership roles—while also maintaining mandatory reporters, to honor the wishes of those reporting sexual harassment. Doing so gives the person reporting/having experienced sexual harassment not only voice but also agency and control. Providing

__________________

5 It should be noted that while these services provide safe spaces for those affected by sexual harassment to talk about their experiences and perspectives, they do not necessarily have implications for sexual harassment policies, processes, and practices, or for the outcomes of a case.

agency in this way for members of groups whose voices have historically been silenced can enhance their trust that their reports will be heard and taken seriously. One institution that makes use of nonmandatory reporting resources is Purdue University’s Center for Advocacy, Response, and Education (CARE), which “provides resources and direct services that are non-judgmental, survivor-focused and empowering.” This center “recognizes that each person’s experience is unique, and staff are available to help each survivor assess their reporting options and access resources that meet personal needs” (Purdue University, 2021a).

Postinvestigation Policies, Processes, and Practices

Institutions can provide opportunities for voice after an investigation has concluded and a finding has been issued. Once the final decision and sanctions (if any) have been clearly communicated, both the individual who filed a report and the person who was accused can be given the opportunity to voice their responses to the decision by appealing or accepting the outcome (see also the section below on correctability). Institutions can ensure that both parties are informed of the outcome of the investigation at the same time, and they can be given the choice of whether to provide their voice or not depending on their individual preferences. One way in which institutions can provide voice equitably is to allow those who have experienced sexual harassment to decide, without pressure, whether to participate in the remediation, reintegration, and acquiring of data that may occur after an investigation has concluded. Institutions can also provide those who have experienced sexual harassment with additional agency in deciding when and how reports of investigation findings are released so their perspectives are not at risk of being excluded or silenced.

Questions for Institutions to Consider When Applying Voice

- How can we ensure that our policies, procedures, and practices are implemented such that all voices are heard?

- How can we ensure that the voices of those who historically have not been included (e.g., those who experience sexual harassment, traditionally marginalized groups, and those impacted by various power differentials) are equitably included in policy and process making and postinvestigation policies, processes, and practices so that their voices are not overshadowed by those of others?

CONSISTENCY

Consistency is the principle that all policies and processes should be equally available, transparent, and accessible across an entire institution, and that corrective actions and rewards should be applied in an even, egalitarian manner regardless of who is involved or when a policy, process, or practice is enacted (Leventhal, 1980). When institutional responses lack consistency, individuals are more likely to believe that the system is unfair (Colquitt, 2004). Additionally, maintaining consistency can positively influence institutional climate—and ultimately prevention of sexual harassment—because knowing what to expect consistently from an institution and those within it builds a sense of reliability and trust. Therefore, it is important to balance an overarching sense of uniformity. As discussed further below, the principle of consistency does not obviate the need for individualized, equitable consideration and treatment of each party and each case; rather, institutions need to achieve a balance between these two overarching concerns.

How to Apply Consistency

It is important to account for two elements in the application of consistency in institutions: consistency with the desired culture and values of the institution, and consistency with institutional policy and state and federal laws (e.g., regulations of the U.S. Department of Education). An example of incorporating consistency with institutional culture and values is the University of California, Santa Barbara’s (2020) creation of department-level codes of conduct that maintain overall consistency with the conduct policies of the entire university. This consistency helps achieve awareness, clarity, and understanding of expectations for faculty, staff, and students (UC Santa Barbara, 2020). Similarly, at Harvard University, the External Review Committee recommended the use of clarifying language and greater transparency for the purpose of improving communication around processes, helping to achieve consistency in the application and implementation of sexual harassment policies (Harvard University External Review Committee, 2021).

The following are examples of strategies for enacting consistency:

-

Within departments and across individuals:

- – Departments/units—While institutions may have standard policies and processes, the specific applications of those policies and processes may differ within the institution depending on the culture, values, contexts, and historical practices of different groups. Thus, a higher education institution can incorporate the principle of consistency by maintaining overarching uniformity of policies across colleges and/or universities within its system while allowing units discretion in how these policies are implemented. To manage the impact of the resulting variability, institutions can implement a process for checking to ensure that the application of policies within units remains consistent with the policies’ goals and requirements.

- – Individuals—While the overarching policies and processes remain consistent, their application to each incident can be individualized through variation in decisions and responses depending on the case and the individuals involved. For example, a consistent institutional policy may be offering support to those affected by sexual harassment, but the form of that support (e.g., meeting with an advocate, counselor, and/or representative of the ombuds office) can differ at the person’s discretion. Institutions can also regularly apply an equity lens when formulating decisions and responses that impact an individual from a group subject to historical inequities.

- Staff support—Individuals with such roles as Title IX coordinator and confidential advocate experience high degrees of work overload, professional burnout, and vicarious trauma (Baird and Jenkins, 2003; Brown, 2019; Houston-Kolnik et al., 2017; Slattery and Goodman, 2009). The result may be staff attrition that in turn leads to inconsistency in the interpretation and implementation of sexual harassment policies and processes. Ensuring that people in these roles are well resourced and supported, that their working climate is healthy and supportive, and that knowledge and process transference is institutionalized are all key to ensuring that policies and processes are applied with consistency.

- Clear language and terminology within an institution and nationally—Having a shared understanding of sexual harassment concepts and applying them across and within institutions facilitates consistency of policies and processes. The American University in Cairo (2019), for example, ensures that its policies are in line with both U.S. and local Egyptian law, given that it is a U.S. nonprofit institution with campuses in Egypt. The use of varying language within

- Transparency—An institution can apply consistency by being transparent throughout the institution and over time. Transparency is facilitated by constant and frequent communications that explain policies, processes, expected timelines, and corrective actions in clear, accessible language. When institutions lack the financial means to provide certain forms of care and support, they can transparently communicate those limitations and provide the community with clear guidance on how various services from outside parties can be accessed. For example, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration developed a website in 2020 to increase transparency and thereby establish a sense of consistency by giving everyone within the agency access to policies, resources, climate assessments, and processes for handling reports related to sexual harassment (NOAA, 2020). Likewise, the Report of the External Review Committee to Review Sexual Harassment at Harvard University (Harvard University External Review Committee, 2021) recommends improving transparency by increasing public awareness of sexual harassment investigations and sanctions.

- Data and evaluation—Consistency of record keeping can be facilitated by providing clear data about sexual harassment–related reports, rates, resolutions, and prevention actions to institutional stakeholders annually while preserving the privacy of individuals. Transparency of aggregated data, as in the annual reports of the University of California, Berkeley (2021) and Yale University (2021a), is another strategy for facilitating consistency of data while retaining individual privacy.

- Training—Institutions can provide training to import a consistent understanding of responsibilities for all individuals responsible for preventing and addressing sexual harassment, such as those who are able to intervene (Powers and Leili, 2017) and those who are required to report cases of sexual harassment (including graduate students and faculty; Holland et al., 2019).

an institution could create confusion about the reporting, assessment, and evaluation of sexual harassment. At the national level, varying language across institutions could reduce the effectiveness of sharing best practices and understanding of sexual harassment.

Questions for Institutions to Consider When Applying Consistency

- How can we ensure that our institutional policies and processes around sexual harassment remain consistent with both the policies and processes established by the state and federal governments and the desired culture and values of our institution?

- How can we ensure consistency and transparency of all of our policies and processes during a sexual harassment investigation?

- How can we maintain consistency and transparency in institutional awareness, evaluation, and data and reports once a case has been closed?

ACCURACY

Leventhal’s (1980) conception of accuracy refers to the idea that policies and processes should focus on information that is precise and free from errors or defects. This principle encompasses careful consideration of the information to be collected during investigations, the error-free retention of relevant information, and the sharing of that information during reference checks. Applying the concept of accuracy in prevention efforts can result in minimizing patterns of sexual harassment from a specific individual and/or unit and maintaining records to share with other institutions.

How to Apply Accuracy

Collecting Information: Retention and Centralization of Information

The principle of accuracy can be implemented through error-free retention and centralization of sexual harassment information, which is important for preventing patterns of sexual harassment from a specific individual and/or unit. Authorized individuals can have access to records and compile relevant information, thereby maintaining both transparency and discretion. In recognizing the principle of accuracy, institutions can record all information about sexual harassment within an individual’s file. They then can ensure that this information is retained without error in that individual’s file over time (66th Legislature, 2020) and is accessible to designated individuals (e.g., investigators and Title IX coordinators) who can maintain privacy and help the institution communicate relevant information transparently. An example is the recommendation of the Harvard University External Review Committee to centralize records. According to the committee, a “single repository for personnel files for University employees … would make the vetting process of individuals for leadership roles much more effective,” and enable the institution to manage and monitor individuals with patterns of sexual harassment and/or previous sanctions for such behavior (Harvard University External Review Committee, 2021). Knowledge of repeated instances of sexual harassment can have devastating consequences for those experiencing the harassment, observers, and the unit involved. Those negative consequences can be exacerbated when information about sexual harassment cases resides with different individuals or groups, impairing the ability to monitor and track such cases with precision and to prevent future sexual harassment. By recording this information in one location, higher education institutions can minimize errors in retaining information over time, proactively note patterns of recurring sexual harassment, and address the behavior of those who have committed it.

Accurately Sharing Information

Accuracy can be demonstrated by sharing information pertaining to sexual harassment with other institutions, as well as potential and current employees and students:

- Potential employees—The University of Illinois, universities in Washington State, and the University of Wisconsin require all potential employees who have been the subject of any substantiated findings of sexual harassment at a previous employer or institution to disclose that information (66th Legislature, 2020; UI System, 2020; UW System, 2021). By encouraging the complete and precise transfer of such information between institutions, these policies ensure that those who have committed sexual harassment are not allowed to transition from one institution to another without the latter’s knowledge of prior sexual harassment.

- Current employees—Institutions can also demonstrate accuracy by including in an employee’s file precise documentation of complaints and allegations of sexual harassment when the investigation results in a finding of responsibility. Substantiated findings of sexual harassment can be considered in making promotion and retention decisions. The professional ethics statement of Rutgers University, for example, explicitly states that teachers and professors must “avoid any exploitation, harassment, or discriminatory treatment of students” and “not discriminate against or harass colleagues.” Rutgers University also incorporated its statement of professional ethics into its promotion and tenure criteria statements for teaching, scholarship, and service, making faculty aware that reliable records of harassment play a role in the institution’s promotion decisions and other disciplinary proceedings (Rutgers University, 2015, 2019b).

Questions for Institutions to Consider When Applying Accuracy

- How can we create and revise sexual harassment policies and processes that support a centralized system that collects and retains information accurately?

- How can our investigation processes ensure accuracy in information while maintaining discretion?

- How are we accurately informing other institutions, potential and current employees, and students of information that will help prevent future occurrences of sexual harassment?

CORRECTABILITY

Correctability is the ability to adjust policies, processes, and practices so that they are constantly improving. Intrinsic to valid and well-functioning policies and processes is ensuring that feedback mechanisms are in place to address problematic structures and identify areas for continuous improvement (Leventhal, 1980). Perceptions of fairness increase when institutions seek feedback on which policies, processes, and practices work well and which do not, and act on that feedback to make changes.

Correctability is demonstrated when institutions can consistently review and revise their policies on sexual harassment (e.g., every 5 years). A mechanism for correction ensures that policies, processes, and practices remain consistent with applicable state and federal laws, are in tune with evolving perceptions of sexual harassment in society, and reflect salient research advances. In reviewing their sexual harassment policies and identifying areas for improvement, institutions can solicit feedback from those most affected by those policies and groups most vulnerable to sexual harassment (see the section on representativeness above). Any resulting revisions of institutional policies can then be clearly communicated to all stakeholders (see the section on consistency above).

Correctability also accounts for appeals within the sexual harassment process, allowing for consistency with state and federal government guidelines (see the section on consistency above). To comply with the U.S. Department of Education’s Title IX regulations addressing sexual harassment with respect to the grievance process for formal complaints of sexual harassment (34 CFR § 106.45(b)(1)(viii)), for example, institutions must “include the procedures and permissible bases for the complainant and respondent to appeal” (ED, 2020).

How to Apply Correctability

Nondisclosure Agreements and Correctability

Incorporation of the principle of correctability is not without potential barriers. Examples include the use of nondisclosure agreements and other methods that potentially undermine the transparency and accuracy of information pertaining to sexual harassment while also limiting the voice of those who have experienced sexual harassment (NASEM, 2018). The U.S. Department of Education’s § 106.45(b)(5)(iii) states that “when investigating a formal complaint and throughout the grievance process, a recipient must … (iii) not restrict the ability of either party to discuss the allegations under investigation or to gather and present relevant evidence” (ED, 2020).6 This suggests that nondisclosure agreements subvert the process of uncovering information about sexual harassment (especially repeated incidents), making it difficult for institutions to correct errors and make improvements. The Washington State, for example,

__________________

6 The U.S. Department of Education’s § 106.45(b) defines sexual harassment (ED, 2020) differently and more narrowly than we do in this paper, and it is specific to formal complaints and grievance processes that address the the U.S. Department of Education’s definition of sexual harassment. Nonetheless, the fact remains that nondisclosure agreements pose a challenge.

addressed the negative effects of nondisclosure agreements through the passage of House Bill 2327, which declares that nondisclosure agreements are counter to public policy and therefore will neither be used in Washington’s postsecondary educational institutions or Washington courts (66th Legislature, 2020).

Appeals and Correctability

Building on federal requirements, correctability can be further reinforced by having an appeals process for the outcomes of an investigation. Institutions can highlight correctability in their investigation process by requiring that appeals be processed in a timely manner. Correctability encourages agency, so that those involved in an investigation can find a way to attempt to revise a decision. For example, institutions can clearly state in their policies who has the authority to make a final decision on an appeal in a sexual harassment case (commonly a chancellor or president) while also indicating that this decision may be elevated for review by an institution’s board of regents or other governing body.

To accommodate differing communication preferences, institutions can also offer informal means of providing feedback, such as an anonymous suggestion box or confidential interviews conducted once an investigation has concluded to evaluate the investigation process and consider what can be improved. Other mechanisms include ethics hotlines and anonymized surveys (Treviño et al., 1999). Institutions also can implement ways to receive feedback when a case is ongoing, such as administering a one-question user survey to gauge the experiences of involved parties at multiple points during the investigation.

Questions for Institutions to Consider When Applying Correctability

- How can we ensure that sexual harassment policies and processes are revised based on feedback from those involved in investigations and the perspectives of those with marginalized and intersectional identities?

- How can we effectively and thoughtfully execute the appeals process and the revision of investigation decisions to correct for errors and/or gaps in the decision-making process?

- How can we address the various barriers that may prevent the correction of investigation decisions and sexual harassment policies, processes, and practices?

CONCLUSION

Incorporating principles of procedural justice is essential if sexual harassment policies, processes, and practices are to be perceived as fair. These principles can help institutions proactively consider how they can address challenges related to these policies, processes, and practices that can hinder efforts to prevent sexual harassment. Establishing a system in which these policies, processes, and practices are perceived as fair can discourage sexual harassment as the culture shifts, encourage individuals to report sexual harassment, and make it publicly known that cases are handled ethically, without bias, with appropriate representation, respectful of voice, treated consistently, recorded and shared accurately, and open to feedback and correction. Specifically, by considering procedural justice principles, institutions can:

- prioritize actions that show care for and support individuals involved in a sexual harassment case (ethicality);

- prevent bias, including implicit bias, by providing education, addressing power differentials, and incorporating third-party bodies (bias suppression);

- consider everyone who should be at the table by including representation of various identities, such as gender, status (student, faculty, staff, administrator) or rank, institutional or organizational roles, race, and sexuality, including, and especially, those involved in sexual harassment cases (representativeness);

- incorporate the input, feedback, and perspectives of relevant parties (voice);

- ensure that institutional responses are transparent and synchronized with government guidelines and stakeholder values and that there is transparency (consistency);

- promote the retention of correct information and data to inform future decisions, including those on hiring and employment (accuracy); and

- require the revision of policies, processes, and practices to reflect feedback and provide the option of an effective appeals process (correctability).

More remains to be learned about how procedural justice principles can apply in various institutional scenarios. Research also is needed to understand the potential impact of increased perceived fairness on the prevention of sexual harassment, as well as how the principles can be applied in the face of various institutional obstacles. Box 3 lists some example research questions.

BOX 3

Example Research Questions

- How can procedural justice principles be used as a supplemental tool for measuring and evaluating how effectively policies and processes may address various components of sexual harassment (e.g., unwanted sexual attention and gender harassment) and change an institution’s climate?

- How can different types of institutions (e.g., public and private institutions, community colleges, minority-serving institutions, unionized and nonunionized institutions) implement the seven principles of procedural justice in the face of such institutional challenges as limited budgets, constrained staff time and bandwidth, and small task forces?

- How can institutions measure, evaluate, and track ethicality, bias suppression, representativeness, voice, consistency, accuracy, and/or correctability?

- How are those affected by sexual harassment in higher education institutions impacted by sexual harassment policies, processes, and practices that incorporate procedural justice principles?

- What policies and processes are effective in enabling ethicality, bias suppression, representativeness, voice, consistency, accuracy, and/or correctability?

- What practices are promising for prioritizing and enacting ethicality, bias suppression, representativeness, voice, consistency, accuracy, and/or correctability while accounting for such institutional barriers as staff burden and whisper networks*?

- How can ethicality vary across institutions or within their units (colleges, departments, etc.)?

- In what other ways is bias observed and consequently needs to be suppressed?

- What are effective strategies and promising practices for institutions to apply to represent multiple parties in policy and process making?

- How can consistency vary across different demographics, cultures, and values within institutional units and across institutions?

- In what ways is accuracy necessary in the investigative process?

* A whisper network is an informal, private channel for the exchange of information among women.