Fare-Free Transit Evaluation Framework (2023)

Chapter: Chapter 3 - Fare-Free Transit Evaluation in Practice

CHAPTER 3

Fare-Free Transit Evaluation in Practice

This chapter reviews the state of the practice of fare-free transit evaluation. This review was informed by a transit agency survey and interviews with staff from transit agencies, community organizations, and transit advocacy groups. The findings from this research informed the development of the fare-free transit evaluation framework.

What Research Has Been Conducted on Fare-Free Transit Evaluation?

Despite growing interest in fare-free transit among U.S. transit agencies, there are few studies on fare-free transit in the United States; most research appears to explore case studies in other countries (Kębłowski 2020). Before the publication of this report, there were no apparent examples of a robust fare-free transit evaluation framework.

Most research on fare-free transit in the United States has focused on small urban areas, rural communities, or university and resort towns where transit agencies provide full fare-free transit. Much of this research was synthesized in TCRP Synthesis 101: Implementation and Outcomes of Fare-Free Transit Systems (Volinski 2012).

Major findings from that report include the following:

- Most fare-free transit agencies serve small communities.

- Transit agencies with low farebox recovery ratios are most likely to implement fare-free transit.

- Some funding sources reward transit agencies for operating fare-free.

- Fare-free transit can be a competitive asset for resort communities.

- Fare-free transit can improve operations on high-volume services.

- Implementing fare-free transit typically increases ridership by 20% to 60%.

- Fare-free transit eliminates fare disputes with operators but can increase the presence of disruptive passengers.

- There can be new or increased costs associated with fare-free transit.

- About 5% to 30% of new fare-free transit trips are made by people switching from other motorized modes.

- Fare-free transit can be a point of community pride.

What Is the Basis of the Evaluation Framework Developed in This Research?

The fare-free transit evaluation framework presented in Chapter 2 of this report was developed based on qualitative and quantitative state-of-the-practice research described in the following. This research consisted of three primary methods:

- A survey of transit agencies at various stages of fare-free transit consideration or implementation.

- Interviews with staff from transit agencies, community organizations, and transit advocacy groups.

- A literature review of academic research, planning work, and journalism on fare-free transit.

More detail on each of these methods is provided in the following.

Survey of Transit Agencies

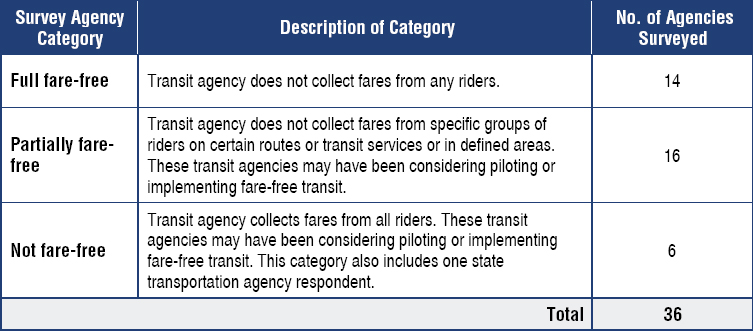

The research team surveyed 35 U.S. transit agencies and one state transportation agency to gather various perspectives on fare-free transit evaluation. The survey respondents represented transit agencies from various categories of fare-free transit (Exhibit 3-1).

The respondent agencies varied in terms of operating size and context. All full fare-free respondent transit agencies served small urban, rural, resort, or university-dominated communities, with smaller ridership, lower farebox recovery, and lower operating expenses than systems in larger metro areas. The partially and not fare-free respondents represented a wide range of transit agency sizes in terms of passenger trips provided, operating expenses, and farebox recovery. Additional information on the methods and findings from the survey is provided in Appendix A.

Interviews

The research team conducted interviews with two types of subjects:

- Transit Agency Staff: The project team identified 23 transit agencies with which to conduct staff interviews and assess as case studies based on the transit agency responses and other research into fare-free transit. These 23 agencies vary in terms of size and type of community served. Staff from the case study transit agencies were interviewed through video conference calls or by email. The role the interviewed staff played in the evaluation or implementation of fare-free transit varied across transit agencies. Interview findings were used to create the case studies in Chapter 4 of this report and inform the findings on the state of the practice and the evaluation framework.

- Staff from Community Organizations and Transit Advocacy Groups: The project team conducted interviews with staff from community-based organizations and transit advocacy groups to gather information on perspectives of fare-free transit from various transit stakeholders. The project team leveraged existing connections with community representatives in Chicago and elsewhere in the United States to solicit feedback from eight organizations. Additional information about the interviews and key findings can be seen in Appendix C.

Literature Review

Throughout the development process for the survey, interviews, and evaluation framework, the project team reviewed various academic and professional research documents, journalistic assessments of fare-free transit evaluations and implementations, and transit agency or consultant reports and briefs. These documents are cited throughout this report.

What Is the State of the Practice?

Findings from the research team’s survey, interview, and literature review work are summarized in the following under two main topics:

- Fare-free transit impacts: The measured and anticipated effects of fare-free transit for transit agencies and the communities they serve.

- Fare-free transit evaluations: How transit agencies have evaluated the impacts and long-term success of fare-free transit in their communities.

Fare-Free Transit Impacts

Fare-free transit has many impacts—both costs and benefits. These costs and benefits are borne by different stakeholders; riders, non-riders, transit agency staff, local government, non-profit organizations, and the broader community are all affected.

The impacts of fare-free transit were commonly cited by survey respondents and interviewees as the primary way transit agencies organized their evaluation and/or monitoring of fare-free transit. These impacts can be organized into two categories:

- Measurable impacts. These impacts can be measured and shown to have been an outcome of fare-free transit. Examples of measurable impacts include changes in ridership, operating costs, or farebox revenue. Although some transit agencies have measured these impacts, many other transit agencies have not. This makes generalizing and predicting measurable impacts of fare-free transit difficult in many cases.

- Assumed impacts. Assumed impacts include costs and benefits that cannot easily be measured, but reason and logic and sometimes qualitative information lead transit agencies to assume they are occurring. Examples of assumed impacts include changes in the perceived or actual safety and comfort of passengers, community traffic congestion, and greenhouse gas emissions.

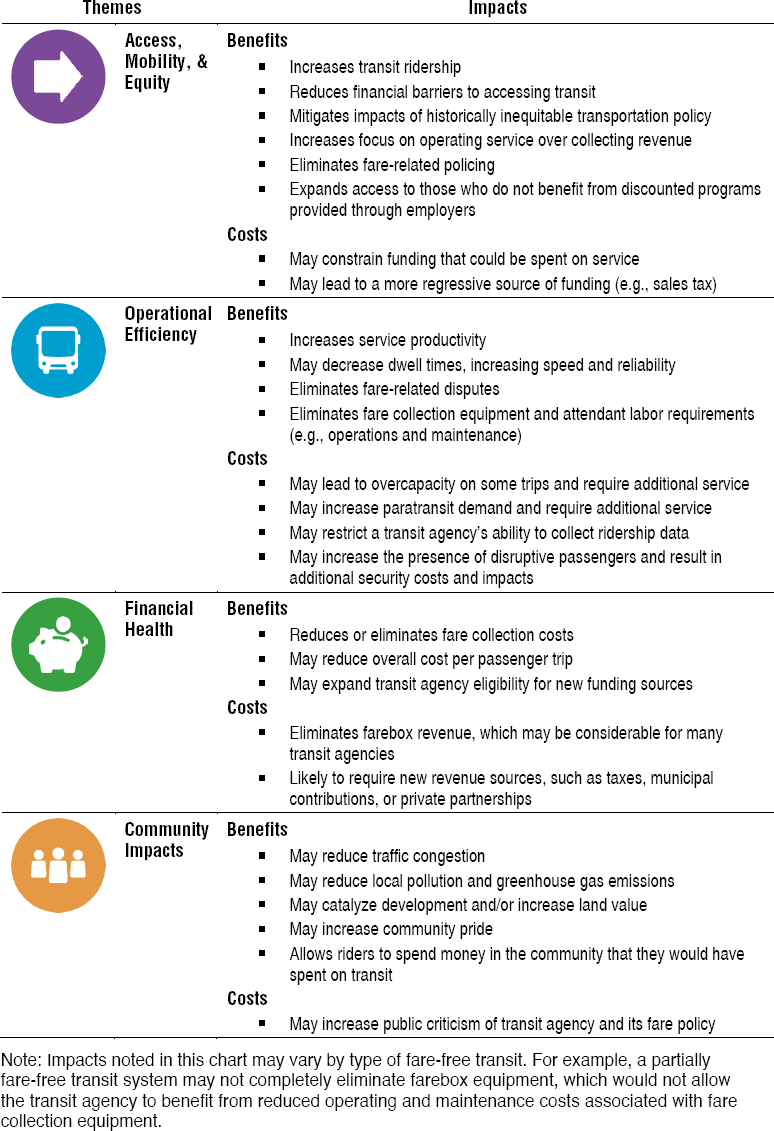

This section summarizes the research team’s findings on the measured and assumed benefits and costs of fare-free transit. Further, the impacts are organized under four common themes: access, mobility, and equity; operational efficiency, financial health, and community impacts (see Exhibit 3-2). Exhibit 3-3 outlines the impacts discussed in this section.

Benefits

The primary benefits from fare-free transit reported by survey respondents and interviewees include greater mobility for community members, social equity improvements, more efficient transit service, reduced fare collection costs, and local economic growth. These key benefits and others are discussed in more detail in the following.

Access, Mobility, and Equity

Survey respondents and interviewees reported that fare-free transit almost always causes an immediate increase in transit ridership. To the extent that a financial barrier to accessing transit is removed for community members, their mobility is also improved. In many instances, this improved mobility means greater access to opportunity (e.g., school, shopping, recreation, healthcare) for community members. Survey respondents and interviewees also reported that fare-free transit is assumed to improve social equity outcomes, as passengers with low incomes save money they might otherwise have spent on transit.

More specific survey and interview findings related to access, mobility, and equity benefits of fare-free transit include the following:

- Transit agencies that went fare-free before the COVID-19 pandemic saw an increase in fixed-route ridership from 20% to over 100% in the first 2 years, especially among those who are young, those with low incomes, and those experiencing homelessness. Most transit agencies that went partially fare-free for only select populations did not see significant increases in ridership.

- Transit agencies experienced a range of paratransit ridership changes after going fare-free, from no change to a 60% increase.

- Transit agencies that piloted or implemented long-term fare-free transit following the COVID-19 pandemic have also seen increased ridership, up to 26% (Northern Virginia Transportation Commission 2021).

- Although some transit agencies already provide discounts to some rider groups, there are often barriers to accessing these discounts, such as personal identification or application requirements and other administrative burdens. The impact of these barriers is clear from observing the low uptake rates of many programs for people with low incomes. Full fare-free transit eliminates these barriers and reduces administrative burdens for both riders and transit agencies (Saphores et al. 2020).

- Partial fare-free transit that is focused in areas and on modes that are most used by minority and youth riders and riders with low incomes allows transit agencies to maintain a source of fare revenue, particularly from riders with higher earnings.

- Existing transit subsidies, such as employer passes, often provide de facto fare-free transit to certain riders, many of whom have higher incomes. This is an inequitable outcome where riders who can afford transit receive discounts, and riders who may benefit more from fare-free transit do not have access to these discounts (Saphores et al. 2020). Fare-free transit can reduce this inequity.

- Fare-free transit can reduce transit agencies’ focus on farebox recovery and increase their attention to service provision based on need, creating a more equitable service that does not consider ability to pay (Cohen 2018).

- Many riders prefer full fare-free transit to partial fare-free transit because the latter may involve fare enforcement, which can lead to overpolicing of racial and ethnic minorities, who are often more likely to be transit-dependent (Perotta 2017, Carter and Johnson 2021).

Operational Efficiency

Fare-free transit may produce operational benefits, such as increased productivity and reduced dwell times. More specific survey and interview findings related to operations benefits of fare-free transit include the following:

- Because fare-free transit almost always increases ridership, it also typically leads to increased productivity, in terms of boardings per revenue hour. This and other efficiency measures can make transit agencies eligible for additional funding, such as STIC funding (FTA n.d.).

- Eliminating fare collection can improve service quality by reducing dwell times through efficient, all-door boarding, without the need for additional technology such as rear-door card readers (Saphores et al. 2020, Volinski 2012, Northern Virginia Transportation Commission 2021). This increases reliability and can offset the increase in boarding time caused by increased ridership.

- Because full fare-free transit eliminates fare collection, it also eliminates the possibility of fare-related conflicts between operators and passengers.

- Full fare-free transit eliminates farebox and other fare collection equipment, which reduces the number of things an operator must operate, maintain, and monitor. This also reduces maintenance employees’ workload and eliminates the step of emptying the farebox when the bus pulls into the base.

Financial Health

Fare-free transit can have financial benefits for transit agencies, such as reductions in fare collection costs, lower operating costs per passenger, and access to more stable funding. More specific survey and interview findings related to the financial benefits of fare-free transit include the following:

- Under full fare-free transit, transit agencies save on existing and future costs of collecting fares including producing and selling fare media; operating and maintaining fareboxes; counting, securing, and transporting cash; and upgrading fare technology.

- Fare-free transit often results in lower operating costs and increased ridership, which reduces a transit agency’s costs per passenger trip.

- Fare-free transit expands funding opportunities that could become more reliable than fare revenue, including grants specific to fare-free transit, grants for increasing operating efficiency, and community funding partnerships (Volinski 2012, Northern Virginia Transportation Commission 2021).

- By eliminating fare collection costs and the administrative costs associated with discounted fares, small to mid-sized transit agencies have been able to lower operating costs and qualify for additional state and federal grant funding for operating expenses (Volinski 2012).

- Transit agencies have used a wide variety of replacements for farebox revenue, including a corporate gross receipts tax, sales tax, municipal general funds, advertising, private partnerships, a dedicated transit tax or fee, or a combination of methods.

Community Impacts

Fare-free transit doesn’t just benefit transit agencies and their riders. External benefits can range from short-term congestion reduction to long-term economic development and civic pride. Many of these benefits align with community goals and priorities at all levels (e.g., stakeholder, transit agency, municipal, state, federal) around equity, mobility, and sustainability. More specific survey and interview findings related to external community benefits of fare-free transit include the following:

- Community members who do not ride transit can also benefit from the ridership increases caused by fare-free transit, as mode shift to transit may reduce carbon emissions and traffic congestion (Baxandall 2021, Kębłowski 2020). Some fare-free transit supporters describe mode shift to reduce carbon emissions as a key reason for supporting fare-free transit. Fare-free transit is also considered by some to increase the quality of life and public health of residents by reducing their exposure to local pollution, also through mode shift and reduction of single-occupancy vehicle use (Kębłowski 2020, Northern Virginia Transportation Commission 2021, Baxandall 2021).

- Fare-free transit almost always improves mobility and access to destinations, which can increase land value for certain uses. This improved access can attract real estate development, which could grow a community’s property tax revenue, as well as provide public realm and infrastructure improvements (Kębłowski 2020, Cohen 2018).

- Many transit agencies with fare-free transit report that their fare-free transit is a point of community pride—even to those who do not use transit.

- Although fare-free transit reduces or eliminates fare revenue to a transit agency, the money passengers save is likely circulated elsewhere in the community, potentially increasing its impact (Mid-America Regional Council n.d.).

Costs

Despite the potential benefits of fare-free transit options, many transit agencies, riders, advocates, and other stakeholders see serious challenges and costs associated with fare-free transit, including fare revenue loss, a potential increase in service requirements, safety and security issues, and other trade-offs. These costs and drawbacks to fare-free transit are discussed in greater detail in the following.

Access, Equity, and Mobility

Negative or concerning aspects of the impacts of fare-free transit on access, equity, and mobility are most often tied to the potential for funding trade-offs. Specific survey and interview findings related to access, mobility, and equity costs of fare-free transit include the following:

- Some transit stakeholders think transit agencies should keep their primary focus on providing higher-quality service, especially to people with low incomes or people living in underserved communities. To these stakeholders, the focus on fare-free transit is misplaced; some argue that making a service free is not as important as making a low-quality service better, even if it costs a fare.

- Transit agencies should ensure that any fare revenue replacement funding sources are not regressive. The equity benefits of fare-free transit could potentially be lost if replacement revenue comes from a regressive source like a sales tax. Some advocates suggest a graduated income tax that ensures those who earn more pay more.

- Eliminating fare revenue may cause service cuts for some transit agencies, which may negatively impact transit riders’ mobility. In areas where the majority of transit riders are those with low incomes or people of color, this may have negative equity impacts. Fare-free transit should not be used as an excuse for not improving service or ensuring access to transit (e.g., meeting Americans with Disabilities Act [ADA] requirements).

- Those who benefit from fare-free transit the most do not always have the time and energy to advocate for themselves, so it can be difficult to measure their priorities. Transit agencies should partner with community groups to disseminate information to their audiences with a particular focus on those with low incomes, people of color, older adults, persons with disabilities, and youth riders. Through this partnership, community groups should be compensated for their time. Additionally, it is important for transit agencies to acknowledge and respond to any feedback received.

Operational Efficiency

Increased ridership from fare-free transit can challenge transit operations. Specific survey and interview findings related to operational costs of fare-free transit include the following:

- The increase in ridership from fare-free transit can cause overcapacity issues on some trips. Some transit agencies have had a hard time supporting increased demand after a fare-free transit implementation. To support increased demand, some transit agencies need to purchase new vehicles, hire new staff, and operate additional service—all of which is costly.

- Because full fare-free transit requires complementary ADA paratransit to also be fare-free3, transit agencies are concerned that the lack of fares will increase demand for paratransit trips to a level that cannot be supported by the transit agency, due to operational (i.e., driver and vehicle availability) and financial constraints. To counter this, some transit agencies tighten paratransit eligibility requirements to reduce demand while remaining in compliance with the law.

- Because hiring can be challenging for many transit agencies, many transit agencies are concerned about the prospect of needing to increase staffing to support fare-free transit (Dolven 2022, Rosenberg 2022).

- Eliminating fare collection may restrict a transit agency’s ability to collect ridership data without fareboxes and fare media (e.g., origin-destination data). This may lead to increased costs for on-board surveys and other data collection methods.

- Many transit stakeholders are concerned about the potential for or actual increase in disruptive riders on fare-free transit. These concerns, which typically are about people with mental health or substance abuse issues, are a major barrier to fare-free transit.4

- Most surveyed transit agencies that had implemented fare-free transit did not find disruptive passengers to be a major challenge after implementation, due to their overall small numbers. Some transit agencies have had success mitigating disruptive behavior with strong code-of-conduct policies, destination requirements, and policies that require disembarking at the final stop.

- Transit agencies that measured the impacts on safety and security incidents after fare-free implementation either saw a slight increase or decrease in incidents per boarding. Many transit agencies experienced reductions in passenger conflicts due to the elimination of fare-related conflicts between passengers and operators (Hodge et al. 1994, Sharon Greene + Associates et al. 2008).

- If transit agencies respond to disruptive passengers on full fare-free transit with increased policing, then this may result in overpolicing of riders who are people of color and riders with low incomes.

___________________

3 Federal Regulation 37.135(c) requires that the paratransit fare for an ADA eligible rider not exceed twice the fixed-route full fare of a similar trip. FTA Circular 4710.1 (FTA 2015) clarifies that the maximum that may be charged for paratransit when the equivalent fixed-route fare is zero would therefore be zero as well.

4TCRP Synthesis 121: Transit Agency Practices in Interacting with People Who Are Homeless (Boyle 2016) noted that transit agencies do not have enough resources to meaningfully help people who are experiencing homelessness who are riding the system. Partnerships with social services, ongoing outreach, and recognizing the humanity of individuals were identified in this report as ways to create a safe atmosphere on transit.

Financial Health

Long-term financial health is almost always the first concern facing transit agencies when they are considering fare-free programs. The impact of fare-free transit on costs and revenues varied widely across the transit agencies surveyed and interviewed, depending on existing ridership, transit agency size, alternate funding sources, and previous fare systems. Specific survey and interview findings related to the financial costs of fare-free transit include the following:

- Full fare-free transit has proven more viable for small- to mid-sized transit agencies than for large transit agencies, as revenue from systems with a lower farebox recovery rate is more easily replaced.

- For larger transit agencies, where fare revenue is a larger portion of operating revenues, considerable replacement revenue would be required for the transit agency to go full fare-free without cutting service. Finding replacement revenue is often cited as the largest challenge to providing partial or full fare-free transit on systems with a high farebox recovery ratio.

Community Impacts

There are considerably fewer negative community impacts from fare-free transit than there are benefits. One negative community impact that has occurred on some systems is an increase in public criticism of a transit agency, especially in the narrative that the transit agency is providing “handouts” to riders that don’t pay their fair share for the service they are using. Although some transit agencies have seen an increase in public criticism, they also typically see an increase in public compliments following fare-free implementation. The prevalence of different responses may vary based on the transit agency’s messaging.

The increase in public discourse in response to a change in policy is not unique to public transit; major transportation policy changes across all modes often result in an increase in positive and negative public discourse surrounding the policy change.

International Fare-Free Transit Context

Fare-free transit has been used as a tool to achieve sustainability goals, reduce congestion, and reduce the cost of transportation across Europe, South America, and Asia. To better understand the international context of fare-free transit, the research team reviewed a 2020 report, Why (Not) Abolish Fares? Exploring the Global Geography of Fare-Free Public Transport, which documented different perspectives on fare-free transit across the world (Kębłowski, 2020).

The report found that more than 100 cities worldwide had made public transit free, mostly in Europe, with implementations ranging from small communities of around 10,000 residents to counties of over 100,000 residents. Key outcomes from the case studies include the following:

- Full fare-free transit programs show that removing fares tends to substantially increase transit ridership.

- Full fare-free transit does not typically reduce car use unless combined with measures to increase the cost of driving, such as congestion pricing, parking pricing, or travel restrictions on personal automobiles.

- Additional benefits include additional access to jobs, increased public satisfaction with transit, opportunities for new funding, cost savings, and traffic safety.

Details on the outcomes from Estonia, France, Poland, and China are provided in the following:

- Estonia. In 2013, Tallinn became the first capital city in the European Union to provide free public transit after the city’s annual public transport satisfaction survey, which had previously

- France. Examples of fare-free transit from France show that eliminating fares can increase customer satisfaction and open doors for new funding sources. In Aubagne, France, implementing full fare-free transit eliminated €1.6 million of fare revenue, which spurred the region to levy a transport tax on large businesses that generates approximately €5.7 million for equipment, maintenance, and labor costs. The subsequent system improvements produced a 136% increase in ridership. Similarly, a weekend-only, fare-free bus program in Dunkirk, France, was extended to weekdays to accompany a network redesign and fleet expansion.

- Poland. Poland features 21 localities with fare-free transit, the highest nationwide concentration in the world. Each of these transit systems abolished fares after 2010, representing a shift in Polish transportation policy. Poland is using fare-free public transit as a strategy to reduce private vehicle ownership and the pollution and noise associated with car usage. In Lubin County, fare-free transit was implemented as part of a municipal social policy to expand access to transportation services. Initial results have been dramatic, as ridership doubled after a year of fare elimination. In addition to ridership gains, Lubin has seen substantial savings due to eliminating fare enforcement (Dellheim and Prince 2018).

- China. While only three municipalities in China offer full fare-free transit, early signs point to the policy’s potential. Gaoping is a small but densely populated city of 72,000 residents in Northern China. The government established free transit in 2013 to relieve congestion, encourage transit use, and discourage illegal motorcycle taxis. A 2015 study found that fare abolition increased transit ridership by 320%. Traffic safety greatly improved due to the subsequent mode shift, providing evidence that fare-free transit could be an effective solution for curbing traffic congestion in countries with high residential density (Shen and Zheng 2015). Changning and Kangbashi offer full fare-free transit as well. Changning’s 300,000 residents make it one of the biggest cities without a transit fare; it serves as an international example for other mid-sized cities with similar transportation policy ambitions. The city of Kangbashi, built in anticipation of high population growth, eliminated the transit fare in 2015 to attract future residents (Kębłowski, 2020).

shown that fare pricing was riders’ most common source of disapproval of the system. Just a year after the introduction of full fare-free transit, ridership increased by 14% while nationwide public transit mode share decreased in Estonia during the same period. Full fare-free transit particularly improved the mobility of residents with low incomes. In the years since fare-free transit was implemented, survey respondents have reported improved access to employment opportunities and a significant increase in overall satisfaction with local public transportation (Cats et al. 2017). Because of the success of Tallinn’s free public transport program, Estonia began a push toward nationwide fare-free public transport in 2018 (Gray 2018).

Fare-Free Transit Evaluations

There are two primary time periods in which fare-free transit can be evaluated: before and after implementation. These evaluation types can generally be described as

- Feasibility Evaluation: Conducted before fare-free transit is implemented, to see if it is feasible for the transit agency. This type of evaluation typically focuses on estimating the likely benefits and costs of one or more types of fare-free transit.

- Post-Implementation Evaluation: Conducted after fare-free transit has been implemented. This evaluation type usually analyzes how successful fare-free transit has been for the transit agency, including measured benefits and costs. Using this information, transit agencies may recommend continuing or stopping the fare-free transit implementation.

Common elements included in both feasibility and post-implementation evaluations as well as detailed descriptions of how feasibility and post-implementation evaluations have been conducted by U.S. transit agencies are provided in the following.

Common Evaluation Elements

Although several research documents synthesize evaluations of partial and full fare-free programs in the United States, there are no standard evaluation methods for feasibility or post-implementation evaluations. This research team’s review of completed evaluations, however, did uncover several common elements of fare-free transit evaluations.

Most fare-free transit evaluations are focused on answering key questions regarding fare-free transit. In TCRP Synthesis 101, the primary questions transit agencies ask were identified through a survey (Volinski 2012):

- Is/was it cost-effective to eliminate the fare collection process?

- What effect did/will fare-free transit have on ridership and system capacity?

- What effect did/will fare-free transit have on service quality and customer satisfaction?

To attempt to answer these questions, transit agencies used a variety of metrics (many of which are measured as estimates), including the following:

- Cost of implementing the fare-free policy (e.g., lost revenue, new service, new vehicles, new facilities) on a per capita basis with the service area

- Change in farebox recovery ratio

- Change in subsidy per rider

- Change in overall service provided (e.g., service hours)

- Savings from eliminating fare collection

- Ridership Impact

- Revenue sources and amounts

- On-time performance

- Fare-free transit’s impact on parking (e.g., utilization, cost, provision)

Some transit agencies also used qualitative metrics to evaluate fare-free transit’s costs and benefits, such as

- Community feedback: compliments, complaints, and general sentiment

- Bus operator feedback: benefits, challenges, and general sentiment

- Issues with “problem passengers”

Feasibility Evaluation

In general, only a few transit agencies have systematically evaluated the feasibility of implementing fare-free transit before implementation. Those that did complete formal evaluations of some kind usually conducted literature, peer, and best practices reviews; operational analyses; and financial evaluations.

Some of the key financial issues that have been identified in feasibility evaluations are the following:

- Many transit agencies struggle to find replacements for lost farebox revenue. Without this replacement revenue, some transit agencies decided against going fare-free, especially agencies with higher farebox recovery rates and larger operating budgets.

- When transit agencies did identify alternative funding sources to make up for lost farebox revenue, they typically looked to taxes, municipal general funds, advertising, private partnerships, state and federal grants, or some combination of these and other methods.

- Many transit agencies did not have a long-term alternative funding source secured when beginning fare-free transit.

In Zero-Fare and Reduced-Fare Options for Northern Virginia Transit Providers, the Northern Virginia Transportation Commission examined regional, national, and international examples of both full and partial fare-free and reduced-fare programs (2021). As part of this assessment, the report identified several key guiding questions to be considered in feasibility evaluations:

- Who is riding transit currently and who would benefit most from the fare options?

- Is cost the determining factor for mode choice?

- What level of ridership growth can be sustained without substantial added investments?

- What are the costs of fare collection and their relationship to loss in revenue from fare-free implementation?

- What funding options might become available under a fare-free system?

In many cases, transit agencies have found that fare-free transit feasibility evaluations provide only high-level estimates of likely outcomes. With the uncertainty associated with these estimates in mind, several transit agencies found it prudent to advance a pilot fare-free transit program, giving the transit agency time to perform a blended feasibility and post-implementation evaluation that produces more information for decision makers. The structure of pilot programs may vary.

Post-Implementation Evaluation

Only a few fare-free transit agencies completed an evaluation after the implementation. Of the transit agencies that performed post-implementation evaluations, the metrics used were largely operational and included

- Ridership

- Revenue

- Passenger or vehicle boarding times

- Additional service needs

- Change in passenger destinations

- Public opinion

When assessing public opinion and other, more qualitative metrics, transit agencies have used several tools, including informal operator feedback, on-board surveys, voter surveys, and online surveys. The post-implementation evaluations that were completed were noted as especially useful in guiding decision makers, such as transit agency leadership or government officials, on whether to continue the program.