Exploring Sleep Disturbance in Central Nervous System Disorders: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 1 Introduction and Background

1

Introduction and Background1

Sleep is a complex biological process (Keene and Duboue, 2018). On average, a person spends about a third of their life sleeping, said Louis Ptáček, professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco Weill Institute for Neurosciences. Yet, despite great strides in understanding the circadian clock—the biological system that regulates sleep and wake rhythms, along with homeostatic sleep drive—Ptáček said little is known about the underlying mechanisms of sleep, how these mechanisms become disrupted, and how to mitigate these disruptions.

Chronic sleep disorders affect at least one in five Americans, said Ptáček. Moreover, a 2016 RAND economic analysis found that sleep loss costs the United States $411 billion annually or 2.28 percent of GDP (gross domestic product) (Hafner et al., 2016). Former Director of the National Center on Sleep Disorders Research, Michael Twery, noted that in 2021 the National Institutes of Health (NIH) committed close to half a billion dollars to sleep research; and current Director Marishka Brown reported that about 60 percent of funding is for basic research and/or research that has a basic (mechanistic) component.

___________________

1 The planning committee’s role was limited to planning the workshop, and the Proceedings of a Workshop was prepared by the workshop rapporteurs as a factual summary of what occurred at the workshop. Statements, recommendations, and opinions expressed are those of individual presenters and participants; have not been endorsed or verified by the Health and Medicine Division of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; and should not be construed as reflecting any group consensus.

On November 2 and 3, 2022, the Forum on Neuroscience and Nervous System Disorders of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine convened a workshop to explore sleep disturbances in central nervous system (CNS) disorders. In recent years, major advances have been made in both clinical and basic research to examine the landscape of the sleep field, said Ptáček, “but there are also huge challenges and great opportunities as well.” To set the stage for the workshop discussions, Heather Snyder, vice president of medical and scientific relations at the Alzheimer’s Association, noted the importance of understanding basic concepts of sleep and its functions.

CURRENT STATE OF KNOWLEDGE

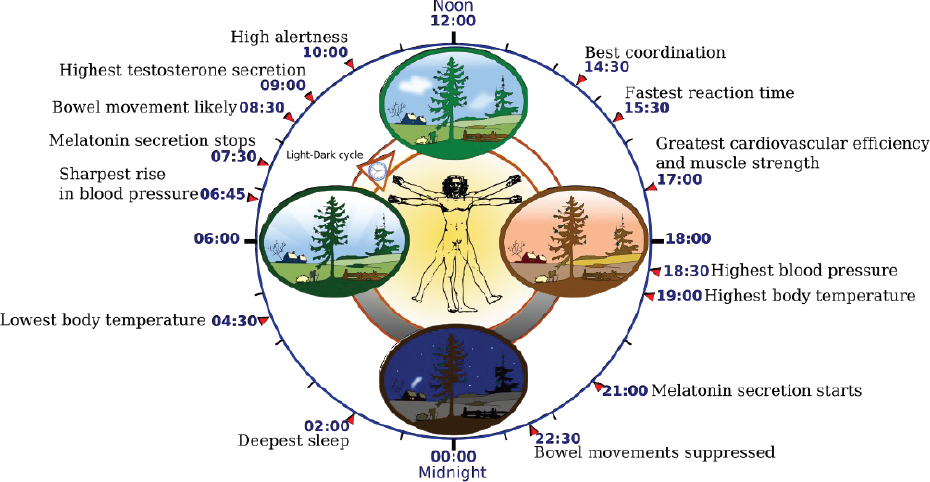

Sleep is a behavioral state that occurs with an approximately 24-hour period, said Amita Sehgal, the John Herr Musser Professor of Neuroscience and director of the Chronobiology and Sleep Institute at the University of Pennsylvania, as well as an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. This 24-hour rhythm, under the control of circadian clocks, drives not just sleep, but other processes as well, as illustrated in Figure 1-1, said Sehgal. “It’s hard to find a physiological process that on some level doesn’t show circadian regulation. That’s how pervasive these rhythms are,” she said.

SOURCE: Presented by Amita Sehgal on November 2, 2022; From Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Circadian_rhythm.

Sleep is also regulated through the homeostatic process, which ensures that an organism gets enough sleep. Thus, after a very late night or a poor night’s sleep, even when the alarm clock and the circadian clock signal that it is time to wake up, the body will try to make up for lost sleep, she said. The regulatory power of the homeostatic process has also been demonstrated in animal models where, despite mutations in circadian clock genes that disrupt the 24-hour rhythm, animals still get nearly normal amounts of sleep, said Sehgal.

The amount of sleep required varies from person to person and across the life span. For example, data from Sehgal’s lab suggest that in very young animals, sleeping for many hours is required for development of neural circuits.

Clinically, many people suffer from primary sleep disorders or from other disorders that are associated with disrupted sleep. Whether the sleep disruption is caused directly by a sleep disorder or is a consequence of other disorders remains an important but unanswered question, she said. To address this and other questions about sleep disturbances and potential therapies for sleep disorders, clinical researchers employ many different measures, which are discussed in Chapter 2.

Yet, to understand sleep on a mechanistic level, animal models are essential, said Sehgal. Indeed, she noted that the 2017 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine was awarded to three researchers—Jeffrey Hall, Michael Rosbash, and Michael Young—who cloned the first gene that affects circadian rhythms in the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster. The genetic mechanism they discovered turned out to be conserved in mammals, said Sehgal. Work pioneered by Louis Ptáček and Ying-Hui-Fu, professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco, further showed that the genes found in Drosophila are implicated in human circadian disorders, she said. Mechanisms of sleep are discussed further in Chapter 3.

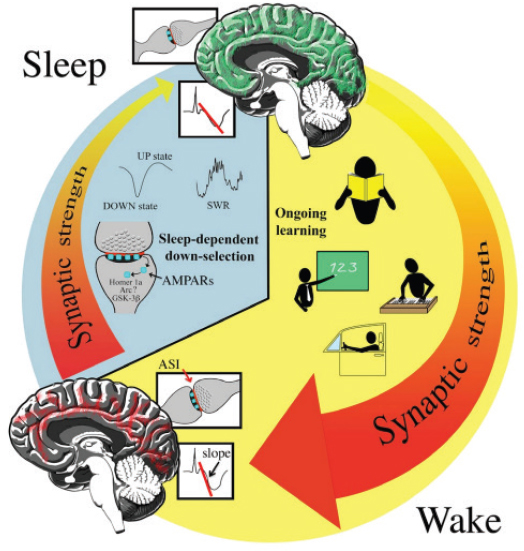

As sleep and circadian rhythm research has moved forward rapidly, a limited understanding of the function of sleep remains. Sleep deprivation is known to affect all aspects of physiology, including metabolism, immune function, and cognition. Indeed, the role of sleep in memory has been recognized for nearly 100 years, she added. Several potential mechanisms for this effect have been proposed. The most popular of these models is called the synaptic homeostasis hypothesis or SHY hypothesis (see Figure 1-2), which posits that activity during awake periods leads to the sprouting of synapses (Tononi and Cirelli, 2020). According to this hypothesis, there is a general downscaling to eliminate extraneous synapses during sleep.

NOTES: AMPARs = Alpha-Amino-3-Hydroxy-5-Methyl-4-Isoxazole Propionic Acid receptors; SWR = sharp waves/ripples

SOURCE: Presented by Amita Sehgal on November 2, 2022; from Tononi and Cirelli, 2020.

Sleep may also be required for the clearance of metabolic waste, said Sehgal. Maiken Nedergaard and colleagues at the University of Rochester have shown that a fluid-clearance pathway, called the glymphatic pathway, clears the brain of toxic molecules such as amyloid-beta—one of the two primary toxic proteins found in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease (Rasmussen et al., 2018). Autophagy, a process by which cellular waste is engulfed in vesicles and then degraded, also appears to be a process that is promoted by sleep, said Sehgal.

WORKSHOP OBJECTIVES

The goal of this workshop was to increase understanding of sleep mechanisms and their effects of these mechanisms on overall human health—with a focus on the brain—from birth to death, as well as the potential to develop interventions that may improve sleep health and address the impact of sleep disturbances on chronic diseases. Although the workshop focused primarily on sleep disorders of the CNS (see Box 1-1), Ptáček noted that people who get poor sleep are likely at increased risk for all diseases.

ORGANIZATION OF PROCEEDINGS

Chapter 2 describes the range of sleep disruptions seen in both primary sleep disorders and as a comorbidity in other disorders. Mechanisms underlying sleep and sleep disorders are discussed in Chapter 3, including circadian, genetic, and circuit-based mechanisms. The influence of light on sleep health and other modifiable targets for several CNS-related sleep disorders are discussed in Chapter 4. Available and experimental treatments for sleep disorders—both pharmacological and non-pharmacological—as well as biomarkers of sleep and sleep disturbances, are discussed in Chapter 5. The final chapter of the proceedings, Chapter 6, summarizes individual workshop participants’ thoughts on research priorities, gaps, and opportunities. Appendix A lists references from this workshop, and Appendix B provides the workshop agenda.