Caring for the Individual Patient: Understanding Heterogeneous Treatment Effects (2019)

Chapter: 5 Next Steps for Implementation

5

NEXT STEPS FOR IMPLEMENTATION

The development of techniques and models for dealing with heterogeneous treatment effects (HTE) and predicting individual risk is the first step in fulfilling the potential of this field. These techniques and models must then be implemented by clinicians. The next-to-last session of the day was devoted to what it will take to move new capabilities related to HTE into the clinic. Much of the information offered in this session was relevant to the patient question: How can clinicians, as well as the care delivery systems they work in, help me make the best decisions about my health and health care?

USING HETEROGENEOUS TREATMENT EFFECTS IN ROUTINE CLINICAL CARE

In the area of HTE, almost all effort—and almost all funding—has been focused on determining which patients will do best with which treatments, said John Spertus, Chair and Professor of Medicine at University of Missouri–Kansas City. “What essentially no one is spending any money or research doing,” he continued, “is figuring out how we move that knowledge into routine clinical care so that we can start to use it every day on patients to help improve the value of care that we deliver.” Yet, that implementation step is equally important, he said. He then described an effort at St. Luke’s Mid-America Heart Institute, where he serves as Clinical Director of Outcomes Research, to take that second step and apply knowledge about HTE in helping patients.

For 20 years, the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR®) has been collecting data on patients and outcomes. “It collects millions of records a year on patients undergoing cardiac procedures, and it builds risk models,” he said. After analyzing that myriad data, NCDR provides hospitals with a quarterly report, including the observed versus the expected rates for a variety of complications, among other information. “Twenty years ago, this was sort of state-of-the-art quality assessment through benchmarking,” he said. However, Spertus said, there was never much interest in taking those risk models and the data and using them prospectively to improve clinical care—to help doctors and patients make medical decisions that were tailored to the risk of individual patients. In response, he and his colleagues did it themselves, creating a computerized decision-making platform they called ePRISM. He explained,

The idea was to take the exact risk models that NCDR was using to risk-adjust the performance at hospitals and enter them with patient-specific data and create clinically useful tools that could be part of clinical care that could allow the heterogeneity of benefit for individual patients to be appreciated at the time you’re making the decision and treating the patient.

Using risk models for individual patients in this way requires that the models be fully integrated into clinical care “so nobody can get through the process of being treated without getting that risk model run,” Spertus said. This process requires a collection of changes to be made in St. Luke’s procedures. One important change, he said, was to the hospital’s consent forms. They were “terrible,” he quipped. The same exact form was used for every procedure, whether it was an angioplasty or a skin biopsy or a liver transplant. It was written at a “16th-grade level,” in legalese,

and was exceedingly vague. The form did not educate or inform, and it did not help either the patients or the providers. St. Luke’s now uses a personalized consent form generated for each patient. This form is much more readable—written at an 8th-grade level, with no legalese, and with pictures to help explain such things as an angioplasty or a stent. Additionally, one key change, Spertus noted, is that each consent form shows the patient’s individualized risk of bleeding or dying from a given procedure, calculated from the risk model as a function of that patient’s personal characteristics. This information helps patients make informed decisions, for example, choosing between a bare metal stent versus a drug-eluting stent. For this choice, patients learn that the choice of the bare metal stent makes it more likely that the blood vessel will close within 1 year and require a new procedure, but the drug-eluting stent requires a much longer period of aggressive anti-platelet therapy, which leads to bleeding and bruising and can cause delays in elective procedures. Now, it is up to the informed patient to decide on the trade-off.

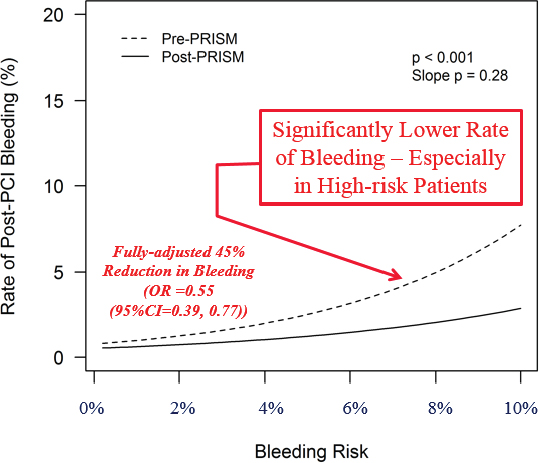

For physicians, the ePRISM system provides personalized information about the procedure and the risks on a monitor in the catheterization laboratory (cath lab) as the patient is being seen, Spertus explained. It also provides a personalized recommendation on the approach to be used. “Literally as you are about to touch the patient, you know what [his or her] risks are, and everybody in the cath lab thinks, ‘This is how we’re going to approach it.’” Spertus and his colleagues tested the system in nine centers around the country with 137 interventional cardiologists, who treated a total 7,408 of patients with a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) to insert a stent. As an outcome, they looked at how often bleeding followed the procedure, comparing the rates of post-PCI bleeding in these nine centers before and after the system was put in place. The system brought about a significant reduction in bleeding, Spertus said, and the decrease was greatest for the high-risk patients. “In a fully adjusted model,” he said, “there was a 45 percent reduction in bleeding when the doctors knew the risks of their patients before they approached them” (Spertus et al., 2015).

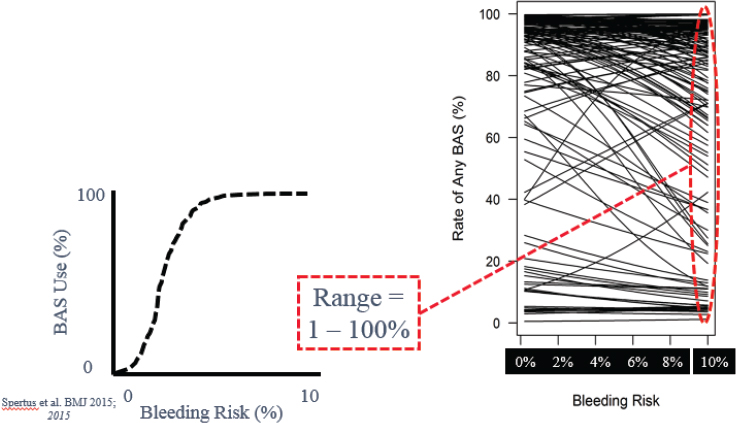

In Figure 5-1, the smooth curve showing the outcome of the trial “hides a lot of messy details,” Spertus said, particularly details about the habits of the individual physicians; he then described what he learned about those habits. Ideally, an interventional cardiologist will modify his or her approach to a PCI based on a patient’s risk. In particular, for riskier patients, the cardiologist should be using one or more of the well-known bleeding avoidance strategies. But when he examined the records of the 137 interventional cardiologists in the trial, that is not what he found. “This is the scariest research slide I have ever generated in my career,” he conveyed. “This is the actual practice pattern of 137 excellent interventional cardiologists at great institutions across the country.” (See Figure 5-2.)

SOURCES: John Spertus presentation on May 31, 2018; Spertus et al., 2015.

He said,

What should just be astonishing to you is that it’s all over the map. Some doctors are always using bleeding avoidance strategies regardless of risk. That’s okay—maybe they’re emphasizing safety. However, some doctors are never using them regardless of the patient’s risk of bleeding. That makes no sense. And the vast majority of doctors are treating the lower-risk patients more than the higher-risk patients, which is completely counter-intuitive.

A patient who needs an angioplasty and chooses one of these centers is assigned to whichever interventional cardiologist is in the laboratory that day and thus has no way of predicting how his or her risk will be handled. “That’s a problem,” he said. “We need to be thinking about physician barriers.” When he examined the individual performances of the cardiologists in his trial, he found that the physicians tended to fall into one of three categories: those whose performance improved with the use of the system, those who stayed about the same, and those whose performance actually got worse. These results reflected the responses of the doctors to having the new ePRISM system in place. “Some doctors, you give them a risk model, and they’re going to improve their performance,” Spertus said. “And some doctors … are going to do the exact opposite of what you and your protocol recommend.”

NOTE: BAS = bleeding avoidance strategies.

SOURCES: John Spertus presentation on May 31, 2018; Spertus et al., 2015.

To understand this situation better, Spertus conducted a study in which he spoke with 27 interventionists at eight centers (Decker et al., 2016). Three themes emerged. The first of which was “experience versus evidence.” Some doctors with a lot of experience in the field felt that their own judgment was all they needed. “Some physicians think that they’ve been doing this for years and years and years and they don’t need someone else’s tool to help them explain to the patient what they think is important.” For these physicians, Spertus said, it will be important to find a way to convince them that the system is not supplanting their experience but rather supplementing it. The second theme was “rationing of care.” Some physicians did not like the idea of treating high-risk patients differently from low-risk patients. Spertus quoted one cardiologist who said, “Restenosis is never higher with a drug-eluting stent, never. So … why wouldn’t you put the Cadillac in everybody?” But today, with the regular emphasis on reducing health care costs, Spertus said, it is important to push for the use of the technique mainly in those high-risk patients who will most benefit from it—which requires knowing who those patients are. The third theme was the perceived value of the process. Some physicians believed they already knew what the system was telling them, so why did they need a form to tell them what to do? “The point,” Spertus said, “is that if physicians alter their behavior and adhere to the risk models, you can

improve the outcomes and the value of health care.… Creating a way for people to embrace the support is very important.”

To do that, Spertus and his colleagues developed a five-step program to get doctors to buy in to the process. The five steps are:

- Identifying a clinical champion, a cath lab leader to drive change;

- Creating a risk-based protocol;

- Implementing a standardized timeout;

- Measuring and sharing performance, which provides feedback and accountability; and

- Celebrating success by developing rewards.

When Washington University implemented this program, Spertus said, the post-PCI bleeding rate dropped from 8 to 10 percent down to 2 percent (Spertus presentation on May 31, 2018). “It’s such a great reduction that every week one or two patients do not bleed in that cath lab who used to.” He noted that about half of the reduction came after the model was implemented, and the rest came after a poster was displayed in the cath lab letting everyone see the percentage of time that each doctor had deviated from the protocol. That feedback cut the bleeding incidence rate in half again.

Toward the end of his presentation, Spertus spoke briefly about shared decision making. According to Spertus, providing patients with a coach to work with when making a decision was a crucial component to improving shared decision making (Ting et al., 2014). When they had a coach, patients were much more likely to have formed a decision on which type of stent they wanted, and they were much more likely to be a part of the decision as to what sort of stent to use, instead of just leaving it to the doctor to decide.

Spertus provided some final thoughts: “Models are meaningless without an effective implementation strategy.” Such models must be integrated into the work flow, and simpler models are better. Furthermore, physician acceptance of a model is critical. Compelling evidence of the model’s effectiveness is important, but not sufficient. Similarly, proof of its benefit is important, but not sufficient. Incorporating accountability and incentives into the system is critical to its success.

APPLYING PHARMACOGENOMICS IN CLINICAL CARE

The next presenter, Josh Peterson, Associate Professor of Biomedical Informatics and Medicine at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC), continued

the theme of dealing with HTE in routine clinical care but spoke in particular about how pharmacogenomics data could be used to make better treatment decisions. To offer some context, he described a 2003 paper (Gandhi et al., 2003) published in The New England Journal of Medicine that examined the adverse drug events that happened to patients in ambulatory care. “The bottom line,” Peterson said, “is if you give 1,000 patients a prescription . . . and you look at what happens to them in the next 3 months, you’ll find that there’s a lot of adverse events.” Most of these events are mainly an annoyance to the patients, but some are serious. Notably, the 2003 study concluded that 3.8 percent of ambulatory care patients experienced a serious adverse event.

The study focused on preventable events, but a large percentage of the adverse drug events were considered non-preventable, he said.

Non-preventable ones were things like serious cutaneous adverse reactions, side effects from selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs], nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug [NSAID]-related GI [gastrointestinal] events, and beta blocker–related bradycardia, where at that time you shrugged your shoulders and said, “Well, there wasn’t much we could do about it.”

One exciting aspect of pharmacogenomics, Peterson said, is that it is starting to turn some of these non-preventable events into preventable ones.

Not all adverse events can be avoided yet; there have been, however, some important successes. One such success involves the rare but serious side effect of Stevens–Johnson syndrome in certain patients who are given carbamazepine to prevent seizures. Patients who develop that syndrome get painful rashes and blisters on their skin, Peterson explained, showing photos of patients with severe cases. It was discovered that the syndrome appears mostly in patients with a particular gene variant (i.e., HLA-B*1502) that is common among certain Asian populations. Several Asian countries now require genetic testing before prescribing carbamazepine, Peterson noted, and doing so has dramatically decreased the occurrence of both Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis.

Another critical aspect of such adverse drug events, Peterson said, is that “there is a frustrating lack of drug efficacy for many of the common drugs we use in primary care.” About 38 percent of SSRIs are ineffective on average, he said, along with 40 percent of asthma drugs, 43 percent of diabetes drugs, and 50 percent of arthritis drugs. This issue leads to a cycle of “Let’s try this drug; well, how about this one?” he said. Such a practice both erodes patients’ confidence in the therapies that doctors prescribe and exposes them to a greater number of drugs, each of which has the potential to harm the patient. The goal then, is to learn how to

integrate various factors—age, drug interactions, pharmacogenomics, indication for therapy, behavioral factors, and others—and predict which prescriptions will be most effective for a particular patient and which ones should be avoided; doing so has the potential to provide clinicians with a powerful tool for dealing with HTE.

Before discussing these prediction tools, Peterson spoke about the spectrum of evidence in pharmacogenomics. In particular, he discussed three areas of evidence: (1) analytic validity, or how well a test determines whether a particular gene or genetic variant is present; (2) clinical validity, or how closely the particular genetic variant being analyzed is linked to the manifestation of the disease of interest; and (3) clinical utility, or how helpful the information provided by a particular test will be to a patient. The evidence is strongest for analytic validity. “One of the nice things about genetics,” Peterson said, “is you can have a lot of confidence in the fact that you have close to 100 percent reproducibility. If you find a variant, you’ll find that same variant, usually with a couple of trouble spots, on multiple platforms.”

A vast body of literature concerning clinical validity exists, as well. Genome-wide association studies and phenome-wide association studies are the most common types of studies supporting clinical validity; the results, however, are still too preliminary to form a strong basis for clinical decision making. Peterson listed two other types of clinical validity evidence, correlations with phenotypic testing and candidate gene studies of clinical outcomes. “And this is mostly what we have to work with when we’re thinking about implementation,” he said. “We’d like to have more clinical utility evidence, which would include randomized trials and comparative effectiveness, but we have to make decisions about what we’re going to do now, today, with the evidence that’s in front of us,” usually without direct evidence of clinical utility.

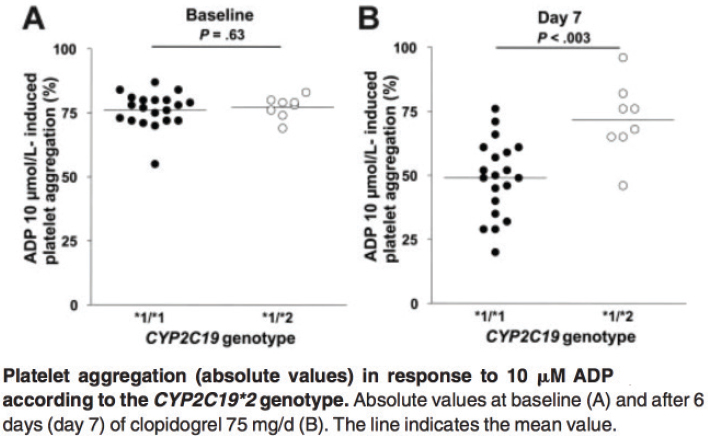

Peterson then offered specific examples of said evidence. “This is the paper that launched a cottage industry in genetics,” he stated, showing a pair of plots from that paper (see Figure 5-3). The paper (Hulot et al., 2006) studied how patients with two variants of the CYP2C19 gene varied in response to the anti-clotting drug clopidogrel. At baseline, the subjects had basically identical platelet aggregation measures (part A of the figure). Yet, 1 week after they were given clopidogrel, those measures looked very different. Patients with the *1/*1 genotype responded to clopidogrel by having about one-third less platelet aggregation, on average, but those with the *1/*2 genotype had, on average, almost no response to the drug. Carriers of the *2 variant also had a poorer clinical response to clopidogrel, Peterson said. Among acute coronary syndrome patients who were undergoing a PCI, the carriers of that variant had significantly more coronary events in the year after they started taking clopidogrel than non-carriers.

NOTE: ADP = adenosine diphosphate.

SOURCES: Josh Peterson presentation on May 31, 2018; Hulot et al., 2006.

Finally, Peterson presented data from a randomized controlled trial of azathioprine, a common immunosuppressant used in patients with autoimmune diseases; the effects of azathioprine in the body depend in large part on how various bodily enzymes metabolize the drug (Newman et al., 2011). Thus, as part of the study, the researchers had analyzed enzymatic activity versus the presence or the absence of a particular genetic mutation. “Patients without the variant have a nice bell curve of enzymatic activity,” Peterson explained. “Those who are heterozygous for the mutation have their enzymatic activity about half of normal. And the one patient homozygous for the variant has no enzymatic activity at all.” The data clearly show how the presence or the absence of genetic variants can shape how individual patients’ bodies respond to drug treatment.

With that, Peterson moved on to describe the Pharmacogenomic Resource for Enhanced Decisions in Care and Treatment (PREDICT) program being used at VUMC to help doctors shape their prescribing to fit the particular characteristics, including the pharmacogenomic characteristics, of each patient. PREDICT helps target pharmacogenetics testing to patients in whom the information is most likely to be relevant in the near future. The system collects data on patients at the medical center in various ways. For example, patients in the cath lab may receive an order from their physician to have their CYP2C19 status tested. There is also a group of patients who are essentially institutionally funded to be

tested before they need any of the therapies. “The idea is to get the information into the record before it’s useful because otherwise there’s a lag that becomes a great implementation barrier,” Peterson said. “If you get your genetic test a week after your prescription, you’ve already incurred a week of risk related to that prescription.” There are now 15,000 patients in the program, and there are several drugs targeted for genome testing, including clopidogrel, simvastatin, and warfarin. “The whole concept,” Peterson said, “is that most of this happens in a semi-automated fashion so that even if you got tested several years ago, you still get some information pushed to you at the right time.”

To get the necessary pharmacogenomic information about how individuals with different gene variants respond to various drugs, the program makes heavy use of the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC®) guidelines.1 The program also engages various clinical experts from the medical center. The result being that clinicians receive a variety of information about how their patients can be expected to respond to various medications. “We sort of automated the results-to-interpretation pipeline to make it as quick as possible,” Peterson said. “As soon as the lab signs off on a result, within just a couple of minutes we get an interpretation that shows up in the patient record in a couple of different places so that people can find these results easily.” He then provided several examples of the sort of information that the clinicians receive.

In one example, SLCO1B1 gene testing in a patient being considered for lipid lowering therapy revealed the *5/*5 genotype, which leads to decreased transporter function and a high myopathy risk if simvastatin were prescribed. The interpretation of this information, Peterson said, was, “Prescribe a dose of 20 mg or lower, or consider an alternative statin; consider routine CK surveillance.”

A second example illustrated the sort of warning a clinician would receive when prescribing clopidogrel to a patient who needed antiplatelet medication but had a CYP2C19 variant that might limit his or her response to clopidogrel. The notice indicates that the patient has a gene variant that is associated with a poor response to clopidogrel and offers some alternatives—in this case, prasugrel or ticagrelor.

The third example was a warfarin adviser who offers a recommended initial dose of warfarin based on a patient’s genetic variants and various other factors. “This is actually a pretty popular form of clinical decision support in our institution, meaning that we get an 80 to 90 percent acceptance rate of the offered dose,” Peterson said. “The bottom line is, this is how much warfarin we think you should give as a starting dose, and we get a lot of uptake on that.” On the other

___________________

1 See https://cpicpgx.org/guidelines (accessed August 9, 2019).

hand, he added, if the clinicians are asked to prescribe a different drug, “that’s cognitively a bigger deal for them, they end up accepting that advice, depending on the scenario, 30 to 60 percent of the time.”

Finally, he showed a form that is provided to patients informing them of their drug sensitivities. It is made available through the medical center’s patient portal. “I don’t know if this is completely adequate in terms of educating them about their pharmacogenomic results,” Peterson noted, “but it is a very scalable way for patients to get access to results so that if they go outside our institution, they still have a way to refer back to the kinds of genetic variants we found.”

IMPROVING PERFORMANCE MEASURES

Rodney Hayward, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine and Department of Health Management and Policy of the University of Michigan and the Ann Arbor Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) opened his presentation with a point that he would return to several times. “So much of what’s wrong with medicine,” he said, “is we want to pretend that we can just talk about the one dimension that we care about at a time. Right now, we’re thinking of quality, and we can’t think of cost when we’re talking about quality. We can’t think of patient autonomy when we’re talking about quality.”

To illustrate, he presented a slide with several typical medical targets: hemoglobin A1c less than 7 percent, blood pressure less than 135/90 mm Hg, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) less than 100 mg/dl, and having had an eye exam within the past year. These goals are assumed to be ones that every patient should strive for, Hayward said. “They don’t consider the heterogeneity among people, and they don’t talk about patient preferences.” He then went into detail for each of these typical medical targets.

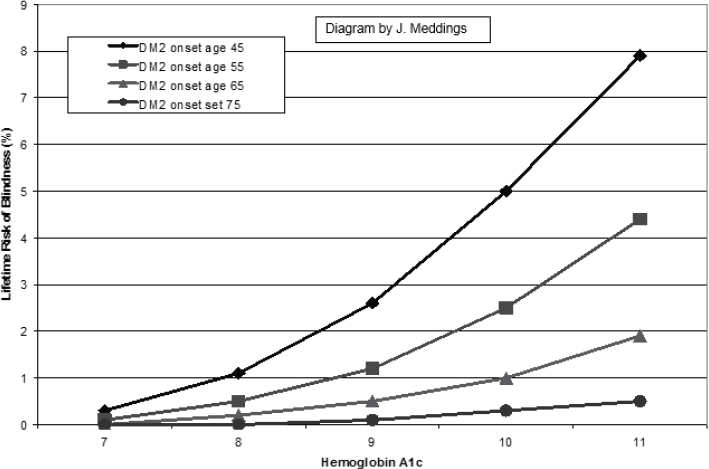

Since 1997, many have known that the standard target for blood sugar is too stringent, Hayward said. That target is getting A1c—a measure of the average level of blood sugar over the past 2 to 3 months—below 7 percent. “Almost all the benefit [of lowering blood sugar] in people with diabetes is getting them to 8 percent,” he said (see Figure 5-4). “But the quality measure is getting them below 7 percent. Most people with type 2 diabetes get almost no benefit from going from 8 to 7 percent. We’ve known this for [more than] 20 years. It still has not changed.”

Something similar is true for the standard 135/90 mm Hg target for blood pressure, Hayward continued. For people with high blood pressure who are at high risk of morbidity and mortality, studies show that the best approach is to prescribe them three or four blood pressure medicines, if tolerated, and not to

NOTE: DM2 = type 2 diabetes mellitus.

SOURCES: Rodney Hayward presentation on May 31, 2018;Vijan et al., 1997.

worry about whether the blood pressure reaches the target (Basu et al., 2016, 2017; Karmali et al., 2018; Sussman et al., 2013;Timbie et al., 2010). Among the high-risk patients, nearly 50 percent will not reach their blood pressure goal, which is not an issue because the use of the medications is most important. With regard to low-risk people with high blood pressure, “once you have them on one or two medicines, you’re close to doing net harm.”

The situation is the same with lipids, he said. High-risk patients with high levels of LDL benefit from taking medications for lowering LDL levels, but they get little to no additional benefit from the LDL levels dropping; and low-risk patients with high LDL get little benefit from the drugs at all. In short, he said, “Your blood pressure and your LDL do not modify treatment effects much at all, and it’s what we base all our guidelines on.… Our dumb quality measures are leading to dumb care.”

The issue with eye exams is different, yet the bottom line is the same. Guidelines call for annual eye exams, but few of the problems that eye doctors see are the result of people not having yearly screenings. About two-thirds of these problems, Hayward explained, are due to failures to follow up with patients who have known retinopathy. About one-third is due to people who are seldom or never screened, who have gone years without an eye exam, and less than 1 percent of these

problems are preventable by annual screening, he said. “We are encouraging waste and harm with all of our performance measures because we do not understand heterogeneity of treatment effects,” he said.

To improve health care in a world of HTE, it will be crucial to develop better performance measures—measures that take that heterogeneity into account. A good place to start, he said, is with the recognition that health care cannot be dichotomized. The typical approach to performance measures is an either/or affair: either the patient should get the treatment or not, and there is a clear cutoff. “We argue that it is a continuum,” he noted. If net value to the patient is plotted along a line, if you are far enough to the right, the benefits to the patient are so great that it is “a no-brainer.” Every patient in that position should get the treatment. If you go far to the left, the benefits are questionable and do not outweigh the costs, hence treatment would not be recommended. In the middle, however, is an area of low to moderate net value for which the patient’s choices become important—that is, when considerations other than the strictly medical ones come into play.

Several problems also exist with dichotomous performance measures, Hayward said, and he identified two types of these measures, strict and lenient. The strict measures have the following weaknesses, he said:

- They do not target those patients most likely to benefit. More generally, they ignore the heterogeneity of patient risk factors.

- They do not help providers optimize or do the “right thing.” They are blunt instruments with little or no clinical nuance.

- They do not take into account patient preferences, and they often mandate care that is not wanted by well-informed patients.

- They can result in unintended consequences, such as wasteful spending.

Lenient dichotomous performance measures have their own problems, he continued:

- They do help target patients who are most likely to benefit. However, they do not promote doing the “right thing.” They do not lead doctors to think about optimal care.

- They do not take patient preferences into account. They ignore the treatments with low to moderate net value that may be of interest to patients.

- They, too, can result in unintended consequences. For example, doctors could focus on the high-benefit people and leave a large number of patients behind because the potential benefit for them is not as high.

What are the alternatives? One approach, he suggested, would be to weigh the quality measures by quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) at risk or some other factor. In particular, a performance measure should take into account—and penalize—overtreatment. Performance measures should also consider individual attributes that modify the absolute risk ratio. They should consider effective, safe treatments that have not yet been deployed. And, he added, “You have to consider partial credit. I have people refuse flu shots all the time.” Patients will not always do what doctors recommend, and doctors should determine how hard to push according to how important the recommendation is.

It is also important for doctors to involve patients in decision making, Hayward said. To make this process easier and more effective, there are various decision tools that can help explain the situation facing the patient and offer recommended choices. When there is a clear yes or no recommendation, the doctor should inform the patient; but the strength of the recommendation can vary, and the doctor should respect the patient’s veto, if it happens. He also recommended that doctors identify the factors that are likely to be most influential in helping the patient decide and present those first.

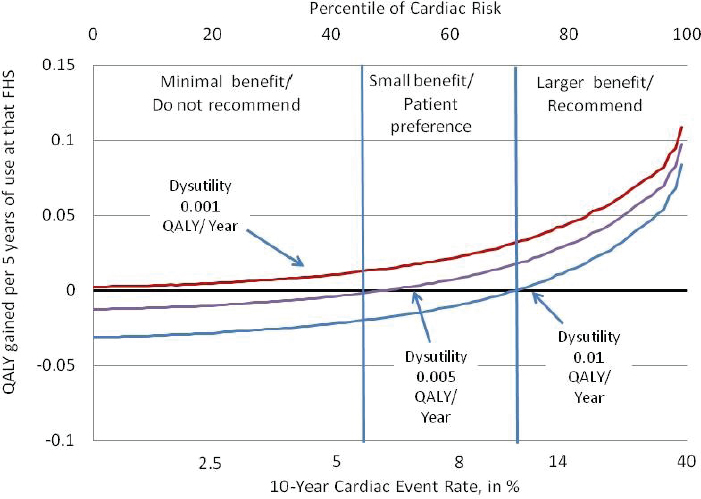

Next Hayward discussed what he called “finding the preference sensitive zone”—that is, knowing when medical considerations make the answer obvious and when a patient’s preferences should come into play. He illustrated this zone with a figure mapping out when a doctor should recommend a patient take aspirin daily to decrease the risk of strokes (see Figure 5-5). In the upper right corner, with high-risk patients who get a large expected increase in QALYs from taking the aspirin, the recommendation is clear: Take aspirin. On the other end, when there is minimum benefit, he would recommend against treatment. And in the middle is where the doctor should talk with the patient about preferences, Hayward said. “In here I say, this is a tough call, but if you don’t mind taking an aspirin a day, this could be reasonable because the main thing that would make this not a good idea is not liking to take an aspirin a day. And that’s because your risk is low, and your benefit is low.”

The preference sensitive zone for lung cancer screening looks very different, however. Risk by itself did not lead to clear decisions; but when risk was combined with life expectancy, it led to very clear recommendations. For people at high risk of developing lung cancer and a life expectancy of more than 10 years, the strong recommendation was always to do screening. “There was no scenario where there was net harm,” Hayward said. “You could hate CT [computed tomography] screening. You could double the false positive rate. It was always net benefit.” Conversely, for people with limited life expectancy or a low risk of developing lung cancer, the net benefit was low, and the decision was best left

NOTE: QALY = quality-adjusted life year.

SOURCES: Rodney Hayward presentation on May 31, 2018; Sussman et al., 2011.

to the individual. But the point to keep in mind, Hayward said, is that “this is doable.” Such decision support systems can be put into practice.

Finally, he concluded by saying that “we have to have a performance management system” running in parallel with decision support. The “performance overlords” are responsible for making it easy to optimize performance, he said. “It’s their responsibility for making these more sensitive, for managing optimal care. Do not let them off the hook. If they give us the tools and they make the measures responsible, then it is our fault. Until then, the over- and under-use is their fault.” The point to remember, he said, is that if people focus only on getting the science right and letting clinicians know about the science, “we will not get there. You need accountability and feedback, and you need tools to make it easier.”

IDENTIFYING CLINICALLY MEANINGFUL HETEROGENEOUS TREATMENT EFFECTS

“I’m actually very impressed with how much heterogeneity is in every aspect of the system,” said Naomi Aronson of the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association, but she added that it is important to keep in mind that not all heterogeneity

is equally important. The classic prototype for heterogeneity of response is the gene-driven response to targeted cancer therapies, for which people with a certain variant will respond well to the treatment and those with a different variant will not respond at all. “It’s very directive,” she said. “What’s important is that it separates patients very clearly.” That is a critical question to ask about any heterogeneity, she said: Does it separate? Does it provide sufficient evidence to tell a clinician how different patients should be treated? Another issue is whether the heterogeneity that is visible in a retrospective analysis will actually be apparent prospectively so that it can be used in directing treatment.

It is also important, Aronson said, to distinguish between patient preference and HTE. The ultimate goal is to learn enough about heterogeneity for patients to be able to express their preference and to offer a truly informed consent. “I would urge us to keep these dimensions clarified,” she continued, “or it really will confound our purpose in that decision making.”

Finally, she warned that developing tests and treatments that take HTE into account may have some unanticipated consequences. If a particular treatment is only effective for a small percentage of people with a disease, and if it becomes possible to identify that small percentage, then the cost of that treatment will be spread over a much smaller group of patients. “Historically, I would say that non-responders have in some way subsidized responders,” she said. “Companies can make treatments for a large population, which spreads the cost, so the average cost is less.” If it is possible to separate out the responders from the non-responders, the average cost of the treatment will be higher, and, furthermore, the non-responders could end up feeling left out, disenfranchised, and unfairly treated, since they are deselected from receiving therapy (albeit a therapy that is likely to be ineffective for them).

Building on Aronson’s comments, Katrina Armstrong, Chair, Department of Medicine, and Physician in Chief of Massachusetts General Hospital said that she had come away from the workshop discussions with four thoughts. First, she said, it will be important to identify criteria for determining which sorts of HTE truly matter. “At the policy level or at the operations level, what I’m really faced with is a ton of potential decisions,” she said. “Out of all the decisions that I’m facing, where does heterogeneity really matter?” It will be important to be able to tell the difference between a “no brainer” decision and decisions that will require a lot of time and resources so that these decisions can be appropriately triaged. It will also be important to determine which decisions will require coaches to help patients understand all the different aspects. “I can’t hire coaches for everybody,” she said. “What metric can I use to say, ‘This is a decision where there is a ton of heterogeneity, and there is something I need to pay attention to?’”

Second, she asked, what is it that we are really trying to predict with HTE? “It’s not the 5-year trial outcome,” she said. “I’m trying to predict my ability to get the patient to the next visit without having hurt them a lot.” Thus, it is important to determine what, from a clinician’s and patient’s perspective, really needs to be predicted. “It is not a single-point decision,” she said, “but it is a journey that we are taking with a patient.”

Third, she mentioned that much of what predicts how well a patient does in treatment is not found in the clinical variables but rather social factors—whether a patient has housing or insurance or social support. So how can one really understand the HTE when so many of the determinants of that heterogeneity are not clinical variables? “I think it’s critical that we try to understand those social variables and how their predictions play out at the same time that we’re looking at diving deep into the clinical variables.”

Finally, she said, it is important to remember that no data are value-free. As an example, she described how Google Translate takes sentences from Turkish—when the pronouns have no gender—and translates them into English. The Turkish pronoun “o” can mean he, she, or it, depending on the situation. If you translate the Turkish sentence “O [cooks]” into English, she said, Google Translate gives you “She cooks.” But if you translate the Turkish sentence “O [operates],” it comes out as “He operates.” Google Translate uses its vast database to guess whether a masculine or feminine pronoun is the more likely choice for a particular situation and uses that to settle on “he” or “she.” It is just data behind the decision, but that decision is not a value-free one.

DISCUSSION

The first question during the discussion period concerned where to start with convincing doctors to use HTE in their practices. Sheldon Greenfield noted that, judging from some of the workshop presentations, generalists seemed less resistant to adopting HTE recommendations than specialists such as cardiologists. Spertus responded that the most important thing is just to start somewhere. Target a few areas, develop the necessary tools, and build the necessary culture, he said, but do it now. Do not delay.

Hayward had a different answer. It will not work to ignore the specialty areas, he said. “You need to deal with the sub-specialty societies,” he explained. “There is no other way. If you go around them, they will win the political battle. All it takes is one prominent cardiologist from Harvard saying, ‘You’re killing people.’” Instead, he said, it is important to find people who are prominent and connected

but open-minded and enlist them to be on your side. You need to be willing to spend the time working to convince such people.

The conversation then expanded to the more general question of what sort of approach it will take to get HTE widely adopted by the health care community. Hayward said that the health care community must recognize that it will inevitably be a long process requiring both a long-term strategy and patience. He quoted Bill Gates as saying, “People dramatically overestimate how much change they can make in 1 year and underestimate how much change they can do in 10.”

Spertus noted that some changes in medicine do happen quickly. It is not always clear why something is adapted so quickly, he said, but psychological factors clearly play a role. Another approach would be to find economic incentives because that will get the attention of the institutions. “There is an opportunity for a lot of creative thinking about creating the incentives to accelerate the change that we’re talking about,” he said. “We just have not been doing enough of that creative thinking to figure those out yet.”