Caring for the Individual Patient: Understanding Heterogeneous Treatment Effects (2019)

Chapter: 6 A Research Agenda for Personalizing Care and Improving Treatment Outcomes

6

A RESEARCH AGENDA FOR PERSONALIZING CARE AND IMPROVING TREATMENT OUTCOMES

The last session of the day was devoted to a look to the future. Workshop participants discussed what is needed to reach the point when the methods for understanding heterogeneous treatment effects (HTE) are more fully developed, as are the tools and the approaches for translating the findings to inform decisions at the point of care (see Box 6-1). The discussion drew on points raised throughout the day to develop a research agenda for the field moving forward. Making progress will require a research agenda focused not only on improving the methods for discovering HTE, but also an agenda focused on best practices for implementing risk models at the point of care and on payment policies that support the effective targeting of treatments.

DESIGNING RESEARCH TO MEET THE NEEDS OF END-USERS

Joseph Selby commented that supporting research designed to understand HTE is extremely relevant to the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute’s (PCORI’s) mission, as it is a central component of patient-centered outcomes research.

Selby then identified four future directions that emerged from the workshop:

- Improve the quality and the availability of clinical data, as well as data from clinical trials, so they can be used to understand HTE.

- Reform the clinical research process, and particularly the pre-approval research process, so trials are designed to understand HTE and “we’re not hit by new therapies for which there is no evidence to help guide who would actually benefit from them.”

- Determine the appropriate role for observational data in research on HTE, as “there’s probably a big role for the large observational data that many can now muster.”

- Understand how to implement the findings of research on HTE, so they are used to inform shared decision making. Ultimately, Selby said, shared decision making will likely be more important in dealing with HTE than coverage decisions by insurance companies.

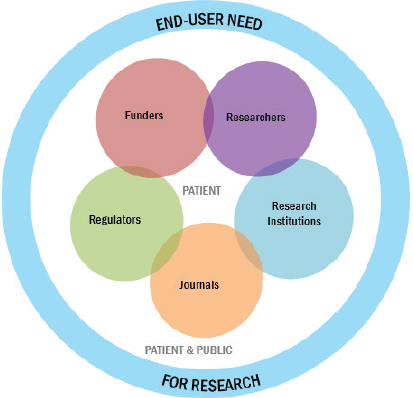

Related to these future directions, Evelyn Whitlock, Chief Science Officer at PCORI, offered a framework for what will be required to move an HTE research agenda forward (see Figure 6-1). “This is a figure that we developed for the work

SOURCE: Evelyn Whitlock presentation on May 31, 2018.

that we’re doing internationally with other research funders looking at what are the levers for improvement to reduce waste and improve value in the research ecosystem,” she explained.

“As many of you are aware,” Whitlock continued, “there has been a movement internationally to look at avoidable waste in research investment,” as well as a variety of other factors that are important to moving the agenda in this area forward, including starting with the end-user in mind and making sure that all research results are available and that the associated data can be accessed by other scientists. As Whitlock explained it, the basic idea underlying the framework is that research should be focused on meeting end-user needs. Building on earlier points made by Thomas Concannon, Seth Morgan, and Christine Stake, Whitlock reiterated that “we need to start with the end in mind, we need to know what’s going to help patients. We need to do it with the involvement of patients and the public.”

At present, she said, PCORI is working to decide on sensible next steps for this research in the coming years. “This is a meeting that illustrates the commitment that PCORI has made in this area.” Specifically, she continued, one of PCORI’s goals is to assemble basic methods for understanding HTE, particularly tools for outcome risk prediction. “If you can accurately predict outcome risk,” she said, “then even if you don’t have treatment effect modification, you’re going to have more benefit in the higher-risk people.” Thus, PCORI is interested in determining what evidence is needed to move forward with these various tools—and also in figuring out if perhaps there are areas for which the evidence is

already sufficient. “Do we have a cadre of established, validated prognostic models that could come off the shelf for some of these situations?” she asked. “There may be more than we’re aware of.”

A RESEARCH AGENDA FOR UNDERSTANDING AND LEVERAGING TREATMENT HETEROGENEITY TO IMPROVE PATIENT CARE

Steven Goodman, Associate Dean for Clinical and Translational Research at Stanford University, who is a co-chair of PCORI’s methodology committee, provided a thoughtful discussion of a number of the philosophical and methodological issues that will need to be grappled with if the application of HTE is to reach its full potential.

One of his main research interests, Goodman said, is the foundations of scientific and biomedical inference or, as he put it, “How do we know that the things we saw are true?” That, he said, was the “fundamental dilemma” underlying much of the discussion that had taken place at the workshop. There are foundational issues facing the field “that we cannot get around,” he said. One of those issues concerns causality and how one determines it. According to Goodman, “Whether one phenomenon that’s predicted by another phenomenon is causal is not found in the data. So, we have to bring other things to the data to determine causality.”

Another key issue is the nature of risk and probability, he said. What is a risk? “It is perhaps the only biomedical property that we cannot measure in the individual.” One can measure such things as height and weight directly from an individual, but determining risk requires working with a group, he noted. You measure risk for that group and then assign the group risk to the individual members of the group. That in itself is a huge leap philosophically, Goodman said—to assume that the risk of the group is the risk to the individual—but having made that leap, one is then faced with a crucial question: What is the right group? This is the reference class problem that David Kent described, Goodman noted. “It turns out,” he said, “that the right group is the group defined by the causal factors of the phenomenon that you’re studying.” But what are the causes of the phenomenon? That’s what you were trying to find out in the first place. “And now we’re in a circle,” he said. “This is an irreducible dilemma. We will always be faced with this dilemma, and many of the debates that we had here today are just transmuting this dilemma into other questions.”

From those two rather philosophical issues, Goodman transitioned into some practical concerns surrounding the study of HTE. The first related to the issue of the likely proliferation of risk-prediction tools as HTE is incorporated into an increasing number of randomized controlled trials (RCTs). “One of the worries

in the decision to start developing risk-stratification or risk-prediction tools in every RCT is that what we will have is a proliferation of these risk predictions based on every RCT,” he said. This is why it is critical to have standard risk-prediction tools, he continued, but very few of those have been developed. Even after a number of risk-prediction models have been developed, it will be a huge challenge to come to agreement on which are the best to use. Noting that it had been suggested during the workshop that risk and benefit models should be developed for every trial, Goodman cautioned, “I think we’re going to have to be very, very careful about how we do that.”

Furthermore, to the extent that the models are predictive and not just prognostic, the issues become even more complex, Goodman said, “because then we’re getting into the issues of causality.” RCTs were developed to assess causal effects, and moving away from the standard RCT model will offer challenges. “I think there are a lot of benefits to come,” he said, “but we’re going to have to be very, very, very careful as we migrate from causal inferences based on randomization to causal inferences based on models…. And I think a number of people have pointed that out.”

A related issue is research reproducibility. As Sanjay Basu demonstrated, two studies of the same treatments can show opposite effects, with one demonstrating net benefit and the other demonstrating no net benefit or net harm. Some of the variation is a result of the eligibility criteria. Those eligibility criteria are an initial reference class, a first guess at which group is likely to benefit from the treatment. “If we start deviating from that reference class and say that only certain ones of these are going to benefit,” he continued, “then we have this question of, Should we, or do we, only focus future RCTs on that subgroup? Or, do we do the reverse? Do we expand the eligibility criteria for the RCT because we want to get information on treatment benefit for everybody?”

Goodman said he felt that there is a tension in the field concerning whether to restrict treatment or expand treatment. In the workshop, he said, he heard arguments both ways, with some saying it should be expanded and others saying it should be restricted. Once a treatment becomes widely used, a related question arises of how to decide which subgroups get the treatment paid for. Goodman urged thinking about the question in terms of the collective population benefit. Sometimes the most population benefit may come from treating the 10 percent at the highest risk, while at other times the greatest benefit may arise from treating the other 90 percent. It is likely that the answer will be different depending on the treatment and the condition, Goodman said. “Where and how we set that cutpoint might be an issue of politics, it might be an issue of economics, but it’s not a given mathematically where that trade-off needs to be.”

Next, he addressed a comment by Frank Harrell that HTE should not be used to rescue failed trials. “I would say, Why not?” Goodman said. If people use HTE tools to examine successful trials and identify subgroups for which the treatment does not work, why not examine trials that show moderate effects that are not statistically significant and look for subgroups of patients who actually benefit from the treatment? “There may be resource reasons why we don’t want to do that,” he said, but “I’m worried about saying that we can’t use it just from a logical standpoint.” Harrell asked for further discussion of this issue.

Then, referring to comments by Naomi Aronson, Katrina Armstrong, and Rodney Hayward, Goodman said that it will be important to think about what sorts of social factors should be incorporated into models. Social factors can influence personal preferences, compliance, and other factors that can play a role in a model’s calculations. Just how much the models should incorporate remains an open question, he said.

Another major question regarding the models is how to determine their effectiveness. The best option he sees is to use RCTs to test the models, just as RCTs are used to determine the effectiveness of diagnostic tests. In one arm, for example, patients would be treated according to the results of a risk-stratification model—which might mean that some patients do not get treated at all—while on the other arm, patients are treated the traditional way, without a model to guide the treatment. As far as judging the quality of evidence from the various models being developed to deal with HTE, “I don’t know that we’re even at the beginning,” he said. “So how are we going to grade recommendations on treating high-risk patients or treating patients with a particular multi-factorial risk–benefit profile from these models? I have barely a clue.” But it is important to start thinking about it now, he said, “because if we cannot figure out what the reliability of this evidence is, we will be caught on the same horns of the dilemma that the guideline developers were in the 70s and 80s when we first started to learn about relying on observational data and clinical trials of varying quality.”

Finally, Goodman said that given what John Spertus had said about the difficulty of getting clinicians to follow even very simple rules from RCTs and systematic reviews, “I worry a lot about the prospect of implementation for these far more complex guidelines.” In conclusion, Goodman said, “We need a research agenda on these models, a practice and implementation agenda…. We need a payer agenda to figure out whether the use of these things should guide what is reimbursed. We need a patient decision-making agenda, and I think we need a political agenda because this is a different paradigm.” The precision medicine paradigm has already broken the ice and prepared the way for the HTE paradigm, Goodman said, “but I think 95 percent of that [precision medicine] is hype. So,

we have to be careful that we focus on the meat here and that we actually use these in a way that does more good than harm.”

DISCUSSION

During the discussion period, Robert Temple from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) raised the issue of why so many clinical trials tend to have people who are very sick—a choice that can make it harder to observe HTE and to determine the net benefits of the treatment for those who are less sick. The reason, he said, is that it allows the researchers to get more “hits” and to test the effectiveness of the treatment for less money than it would take if the subjects were less sick. So, he said, “in cardiology the first study we get is in people who are high risk. If you want to know if the drug works in anybody, that’s how you find out.” It is called “prognostic enrichment,” he said.

That triggered a wide-ranging discussion of inclusion and exclusion criteria for clinical trials. One alternative, Ravi Varadhan, Associate Professor of Oncology at the Johns Hopkins Center on Aging and Health, commented, would be to choose subjects for trials in a way that is parallel to how surveys are done, with careful attention paid to obtaining a representative sample of the population. Jesse Berlin, Vice President and Global Head of Epidemiology from Johnson & Johnson, suggested that “there ought to be a way to build randomization in a pragmatic way into actual clinical practice” so that the results of clinical practice could be used in the same way as RCT data. There would be ethical issues to be discussed, he acknowledged, but “the idea is to turn this into a real learning health care system.”

Sheldon Greenfield suggested combining RCTs with observational studies. The Women’s Health Study did something similar, he said. Steve Goodman agreed that combining observational studies and RCTs was important, as is combining analyses from multiple observational studies, especially since “there are a lot of initiatives going on right now to mimic RCT evidence with appropriately designed observational evidence.” There are many domains for which observational evidence is very important, he said, and others for which it is not.

Robert Golub, a Deputy Editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), spoke about issues related to communicating HTE results. “I would like you to think about how to communicate these types of findings within journal articles to clinician readers,” he said. “I am convinced that most of our readers do not really understand most of the things that JAMA publishes. They may understand the basic outlines of an RCT, but that is pretty much

it.” Communicating HTE results accurately will be even more difficult than communicating about RCTs, he said, so it is important for those in the field to identify effective ways to communicate the concepts and help clinicians understand the nuances of the work. It is not enough just to provide tools to tell clinicians what treatments to prescribe in which situations, he said—that is just turning clinicians into technicians. “Clinicians need to understand the research that is behind that.”

CONCLUSIONS

As stated by Whitlock, numerous speakers over the course of this workshop provided convincing demonstrations that variations in baseline outcome risk can be expected to influence absolute treatment effects in treatment-eligible patients, that meaningful variation in outcome risk is quite common among trial participants and treatment-eligible populations, and that the subset—and often a minority—of trial participants who are at higher baseline risk for the outcomes the treatment addresses will often drive the finding of overall benefit.

However, while there are examples of risk models being used to tailor care, the methods for modeling these effects and for implementing those models in clinical care to personalize treatment decisions are still in their infancy. In order to facilitate progress, the field must not only address outstanding methodological questions, it must also determine best practices for implementing risk models and predictions tools in clinical practice so they can be used by patients and clinicians at the point of care to inform treatment decisions and consider appropriate value-based payment models that effectively target treatments to subpopulations that are most likely to benefit. Therefore, key directions for the field include

- Developing guidance on approaches for assessing the effectiveness or validity of predictive and prognostic models;

- Understanding the comparative performance of supervised machine learning methods that can be applied to understand HTE;

- Facilitating collaboration and leadership across various sectors of the research ecosystem to create prioritized opportunities for large trial re-analyses or collaborative individual patient data analyses to examine the HTE most likely to impact population health;

- Describing approaches to implementing risk models in clinical care and providing guidance on which approaches are most effective at informing decisions both at the point of care and at the level of the health care system;

- Considering approaches for integrating data related to the social determinants of health into risk prediction models;

- Determining the role for observational data and when it is appropriate to combine RCTs and observational data;

- Reforming the predominant fee-for-service payment system in the United States to one that rewards value and population health improvements;

- Promoting dissemination of innovative trial designs, including those sampling larger and broader populations to enrich patient heterogeneity; and

- Establishing or extending research reporting guidelines to promote the conduct of predictive HTE analyses.

Understanding HTE can transform medical care by increasing the likelihood that patients will benefit from the treatments that are offered to them and by contributing to the goal of avoiding harmful or wasteful treatment choices. Patients want precise answers about how a given treatment is likely to work for them, given their unique individual characteristics. A one-size-fits-all approach to treating a medical condition based on average responses from clinical trials is inadequate; instead, treatments should be tailored to individuals based on heterogeneity of their clinical characteristics and their personal preferences.

This page intentionally left blank.