Experimental Approaches to Improving Research Funding Programs: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 1 Keynote Presentations

1

Keynote Presentations

Each day of the workshop began with a keynote presentation introduced by planning committee member Adam Jaffe. The first day featured Sasha Gallant of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), who offered perspectives on the potential of experiments from the work of the agency’s Development Innovation Ventures, which she leads. The second day featured Shirley Tilghman, the former president of Princeton University, who brought the perspective of both a research scientist and a manager of scientific research.

This chapter summarizes these presentations, beginning with that of Shirley Tilghman because her remarks touched on many of the themes that emerged over the course of the workshop.

EXPERIMENTS IN PEER REVIEW AND FUNDING

Shirley Tilghman introduced her thoughts on experimentation in science funding by reviewing the findings of the Expert Panel on International Practices for Funding Natural Sciences and Engineering Research. Conducted for the Council of Canadian Academies, the charge to the panel, which Tilghman chaired, was to look internationally at successful practices for funding natural sciences and engineering research and at how such practices could be applied to funding for this research in Canada. As described in its 2021 report Powering Discovery, the panel and its staff reviewed the literature and interviewed experts from Asia, Europe, and North America to learn about practices elsewhere. It also spent time learning about the funding of science by foundations around the world, “because, interestingly, they appear to be doing some of the most interesting experiments.”

One remarkable thing the panel found was the amount of convergence among countries in terms of the challenges they face. First, Tilghman said, a fundamental decision for funding agencies worldwide is whether to fund the “best science” or to take other considerations into account, such as the stage of an investigator’s career. For example, both the European Research Council and the

Dutch Research Council segment the applicant pool into three categories. The European Research Council offers three types of grants:

- starting grants of up to 1.5 million euros for 5 years for promising early-career researchers with 2–7 years of experience after a PhD,

- consolidator grants of up to 2 million euros for 5 years for promising researchers with 7–12 years of experience after a PhD, and

- advanced grants of up to 2.5 million euros for 5 years for established research leaders with a recognized track record of research achievements.

Proposals for each of the three career stages are reviewed independently by review panels, and specific budgets are set aside for each grant type. “These were very specific efforts on the part of these two agencies to ensure that there is workforce pipeline flow through the system,” Tilghman said. “We thought this was one of the most interesting programs that we saw.”

A second key consideration in designing funding programs in science is whether to fund an individual or a project. The best comparison in this case is probably between the funding for investigators by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) and the project grants funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) or the National Science Foundation (NSF). HHMI “cherry picks” people of high achievement in science and provides them with generous funding to reduce the “overwhelming demand that many in the field feel to be continually in the grant-writing process,” Tilghman said. HHMI also provides 7 years of funding, which provides enough time to take risks that may not be possible with shorter grants. “The day I became a Hughes investigator I changed everything I was working on because I knew suddenly I had a 7-year runway to do something different.”

Third, countries expressed a common desire to fund high-risk, high-reward science. “This is the thing we heard more than anything else from agencies that we talked with around the world,” reported Tilghman. However, the panel was able to find very few examples of agencies that thought they were doing this well. Representatives of agencies said that the increasingly competitive nature of science has made reviewers risk averse, which tends to work against high-risk projects. Instead, reviewers tend to regress to the mean rather than finding exciting new ideas.

A potential solution to this problem, she said, is to take note of the variance in reviews: “The grants you might want to pay attention to are the ones where the variance is wide, because those might be the ones that have a really interesting idea that’s worth taking a risk.” Similarly, risky ideas might be promoted by issuing all members of a review panel a “golden ticket” that they can

use once to fund a project they find particularly exciting.1 Longer grant durations and increased flexibility in the research supported by a grant are also more successful in promoting risk-taking, said Tilghman.

Along these lines, Tilghman described a novel approach to research funding that began after the Powering Discovery report was released. Reid Hoffman, founder of LinkedIn, and other philanthropists have helped fund a program called the Hypothesis Fund, which has the motto “nimble funding for nimble minds.” The idea is to provide philanthropic seed funding in multiple disciplines to support bold new basic science ideas. The Hypothesis Fund has empowered a network of “scouts” to identify high-risk, high-reward research for funding through seed grants. Grants are in the range of $300,000 and extend for 1–3 years. No long grant application is required, and the funding is provided as soon as the scouts report. The first group of people who were supported has been “amazingly diverse” in terms of race and cultural background, gender, geography, institutions, and career stage, observed Tilghman. She said, “This is clearly not a model for federal funding, but it is a response of at least one philanthropist to trying to get catalytic money in the hands of people who have exciting new ideas.”

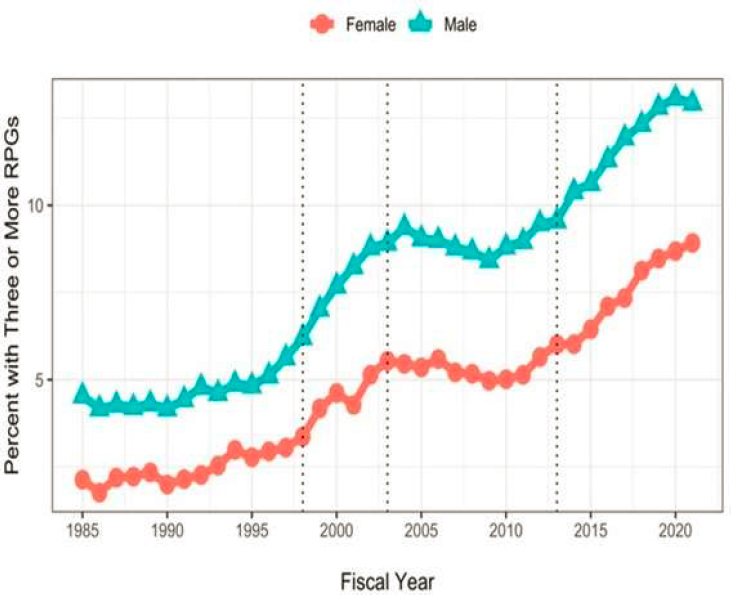

Fourth, the panel considered whether to skew funding to top investigators or to “spread the wealth.” For example, the number of investigators with three or more NIH research project grants has more than tripled since the 1980s, to about 15 percent for men and 9 percent for women: see Figure 1-1. “What is the best strategy for funding science,” Tilghman asked, “funding those who are most likely, based on prior productivity, to produce the most important science, or funding as equitably as possible?”

Tilghman discussed several interesting experiments in peer review being explored by various countries to counter the increasing competition, low success rates, administrative burdens, and bias associated with peer reviewing, along with the difficulties caused by investigators applying for multiple grants and the problems that arise when reviewing multidisciplinary grants.

One category of experiments involves controlling the number of proposals researchers can submit. For example, the Dutch Research Council postpones calls for proposals if the expected success rate falls below 25 percent. The U.K. Research and Innovation agency permits investigators to participate in only one competition per year if the prior success rate was below a certain threshold. And many organizations are exploring multistep applications, such as short preproposals that are triaged. For example, the Marsden Fund in New Zealand triages 84 percent of applications with a one-page initial proposal; this kind of strategy is also used by many philanthropies with a limited ability to make grants.

___________________

1 Although it was not mentioned in the workshop proceedings, a recent article provides additional discussion of the debate over the use of golden tickets: Singh Chawla, D. 2023, February 24. “Golden tickets” on the cards for NSF grant reviewers. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-00579-z

SOURCE: Presentation by Shirley Tilghman.

Another category of experiments involves the peer-review process, Tilghman explained. One example is having applicants review each other’s proposals. This approach has been used by the Dutch Research Council; the U.K. Biotechnology and Biological Research Council; and, in the United States, the Research Corporation for Science Advancement (Scialog) for relatively small competitions. Alternatively, many organizations, including the Dutch Research Council, the Volkswagen Foundation, and the New Frontiers in Research Fund in Canada, use double-blinded reviews, in which the identity of the applicant is hidden so as to focus reviewers on the quality of the science rather than the identity of the applicant. (Tilghman noted, however, that she believes that the identity of the applicant is often known despite being blinded to the reviewer.) Some organizations have used partial lotteries after the screening of preproposals, including the Health Research Council of New Zealand to support high-risk high-reward science and the Volkswagen Foundation in Germany to support “bold new ideas.”

Not all countries and institutions are focused on diversity, equity, and inclusion, Tilghman stated, but a number are. For example, some, such as the

Gates Foundation, are conducting double-blinded reviews at the preproposal stage in an effort to increase diversity; others, such as the Villum Foundation in Denmark, use double-blinded reviews throughout the review process. Some are redesigning the biographical sketch to emphasize quality over quantity. The United Kingdom has been particularly active in creating equality charters, which are voluntary efforts on the part of institutes to be reviewed for their policies around diversity, equity, and inclusion. Canada and New Zealand, in particular, have targeted research programs with special review panels for Indigenous populations, and many countries are including progress in diversity, equity, and inclusion among grant review criteria.

Tilghman concluded with two general observations. First, “science is changing, and the way in which we fund science should be changing as well to respond to that fact.” When she started in science, she explained, her own field of developmental genetics was a “cottage industry,” with little imperative to reach out and collaborate with others. “My field is now completely different, where it’s virtually impossible to function as an island.” Second, experimentation is essential, but experiments need to be evaluated if they are to be useful. “In looking at all of these experiments that are going on, we found almost none that were doing serious or rigorous evaluations,” she said. Evaluations are hard, but they are the only way to know how changing procedures could improve the quality of science.

Much of the discussion during the question-and-answer period revolved around the desire to fund high-risk, high-reward research. In response to a question about why countries favor this kind of research over research that, for example, would be expected to have the highest social value, Tilghman pointed to the attraction of making a major discovery. “Everyone wants to be able to say that they were responsible for identifying the next CRISPR-Cas9, to take an example out of my own field.” Of the countries her panel studied, Canada focused the most on social issues, particularly issues in the north related to climate change.

Tilghman also pointed out that a focus on high-risk, high-reward research can be taken too far. Funding a broad portfolio of research projects is necessary to build the foundation for riskier science. Agencies need to fund what she called “curiosity-driven research that appears to have no higher goal.” The impact of this foundational work is often not apparent in the time frame considered by a reviewer. “There are so many good examples of work that wasn’t seen as groundbreaking when it was first published but then became absolutely critical 10 years later,” Tilghman explained. Even when a major discovery is made, many gaps surround that discovery and need to be filled. Similarly, great science can be done anywhere, not just in major research centers, which supports the argument for spreading funding across geographies and institutions.

Finally, asked about whether artificial intelligence might offer a way to compare proposals or generate new ideas, Tilghman responded that “having just spent the last month, like everyone else in the country, reading about Chat GPT and the lousy college essays it produces, I’m skeptical.” But experiments should

be done. “I don’t think it’s going to replace human imagination and judgment, but it might be a good tool to help in the evaluation.”

A MODEL PROGRAM AT USAID

In her keynote address, Sasha Gallant discussed the model that her team has used to integrate research and experimentation for social impact and what they have learned about the synergies between rigorous experimentation and innovation.

Innovation is critical in solving most of the toughest long-standing development challenges, she said. “But there are many important cases where commercial incentives for innovations are less—often far less—than the social benefits they generate.” In such cases, the government often has a key role to play in investing in critical areas of innovation and integrating research and experimentation into innovation processes to maximize social impact.

Government involvement in innovation also has inherent challenges, said Gallant. Bureaucratic procedures can slow funding processes beyond what is tenable for smaller organizations. A fear of failure and relying on government funding alone can cause important new opportunities to be missed. Not learning from what has been done can lead to throwing good money after bad. “For those of us in government,” stated Gallant, “the challenge is to figure out how to target investments in social innovation where they’re most needed, and how to structure funding in a way that reflects some of the agility of the private sector while maintaining our focus on social value.”

Evidence points to high rates of return on government investments, Gallant said, citing estimates that past public investments in research and development in the United States have had an annual social rate of return of 55 percent. Less evidence exists regarding rates of return in the social sciences or social entrepreneurship more broadly, although there are anecdotes of both success and failure. Gallant continued, “Today, I want to add a few more anecdotes of success to the narrative and speak to the evidence showing how tiered evidence and experimentation-driven innovation funding from the public sector can drive results.”

Development Innovation Ventures (DIV) at USAID is a tiered, evidence-based, open-innovation fund that offers flexible grants to test new ideas, build evidence of what works, and scale breakthrough solutions that address some of the world’s toughest development challenges. USAID priorities and internal staff are the primary actors in determining the problem set, the solution set, and which actors to engage. This approach poses some risks, because some important things might fall between the cracks of an organization’s priorities. DIV counters this risk by seeking good ideas from anyone, Gallant said: “We accept applications year-round from innovators and researchers working across every sector and every country in which USAID operates.”

USAID defines innovation broadly to include anything that enables more social value to be created with fewer resources, encompassing everything from

technologies to policy innovations to behavioral influences. It is open to innovations that are seeking to scale through any pathway, including commercial growth, support from local governments or donors, or philanthropic support. It accepts applications from all types of applicants, from researchers to firms to government partners.

This wide-open approach requires structure and rigor to discipline funding decisions, Gallant observed. To do that, DIV employs a tiered funding model in which small amounts of funding are provided for pilots of a broad range of promising ideas. Before large-scale funding is provided, innovations undergo rigorous testing of impact and cost-effectiveness, often, though not always, using randomized controlled trials (RCTs). DIV offers three tiers of grants:

- up to $200,000 for pilots (Stage 1),

- up to $1.5 million to rigorously test or assess the market viability of a particular product or service (Stage 2), and

- up to $15 million for further expansion (Stage 3).

Innovators can compete at any time and at any stage, not just at Stage 1, if previous progress has already occurred. Also, evidence grants of up to $1.5 million are awarded to relatively new ideas to evaluate development approaches that are widely used but do not yet have evidence to show that they are cost-effective or meaningfully improve people’s lives. Since 2010, DIV has supported more than 90 RCTs, many of which have been led by some of the top development economists in the world.

To work across so many sectors and geographies, Gallant explained, DIV relies on hundreds of experts within and external to USAID to review proposals and select awardees. It also uses three cross-cutting selection criteria to provide rigorous evidence of cost-effectiveness and the potential for scale. First, demonstrating rigorous evidence of impact means testing whether and how an innovation works and, whenever possible, isolating the impact from potential confounding factors. “We have found that the experimental method supports the process of continual improvement and can be a powerful tool to inform policy and promote innovation and development,” she said. Second, cost-effectiveness means that an innovation demonstrates the potential to deliver more impact per dollar than alternative solutions by reducing costs, increasing impact, or both. Third, supporting impactful solutions means demonstrating the potential for scaling up, in order to improve the lives of at least 1 million people while achieving financial sustainability commercially or through sustained public financing.

Whether projects are funded by a government or by private investors, all projects face risks. Gallant pointed out that risks include fraud, the possibility that outcomes will not be achieved or sustained, and that results could have been achieved better, faster, or cheaper. DIV’s approach is designed deliberately to mitigate risk, said Gallant. Thousands of ideas compete, and hundreds of internal

and external experts vet proposals, “which raises our bar for creativity [and] also for quality.”

A core part of the innovation process, Gallant stated, is accepting that failure happens and learning from it. For DIV, the staged funding approach allows relatively small amounts spent on unproven approaches to be reallocated if necessary. “When we fail, we fail quickly and cheaply,” she said. “We learn from it, and then we focus resources toward more promising solutions.” During the award period, DIV conditions payments on achievement of milestones. “This flexible funding mechanism helps us manage risk both for USAID and for the innovator while providing the flexibility needed to iterate and adapt as our awardees work to achieve each milestone.”

Since 2010, DIV has reviewed more than 13,000 applications and has supported 277 awards in 49 countries, Gallant reported. “The demand for this type of innovation funding, at least in the international development space, is tremendous.” Half of these awards have been to organizations that have never before received funding from USAID.

This support has achieved major successes, Gallant said. For example, although school enrollment worldwide has been steadily increasing for decades, over half of the students in low- and middle-income countries still progress throughout school without gaining foundational skills. In response to this challenge, an Indian nongovernmental organization developed a learner-centered approach called Teaching at the Right Level (TaRL) that helps students catch up in reading and mathematics, which since then has been replicated in sub-Saharan Africa. “Today,” stated Gallant, “TaRL is recognized as one of the highest-impact and most cost-effective learning interventions, benefiting millions of children globally and being considered by other partners in USAID as a critical part of the post-pandemic learning strategy.”

Also supported by DIV, innovative cash transfer programs have helped thousands of households improve their standards of living while attracting funding from external interests. Gallant related that, in 2019, DIV funded researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University to work with the government of Indonesia to conduct an RCT to evaluate the impact and cost-effectiveness of transitioning one of the world’s largest social benefit programs from physical rice distribution to direct purchase through an electronic debit card. According to this experiment, millions in the program started receiving the total amount of food intended for them 81 percent of the time, up from 24 percent of the time prior to shifting to digital implementation. Initial results showed that the new electronic system led to a 20 percent decrease in poverty among the poorest 15 percent of households at the same cost as the traditional program.

Beyond project-level outcomes, an examination of portfolio-level outcomes reveals the value of the tiered, open funding model, Gallant observed. DIV does not expect every investment to be successful, but it expects that enough of them will succeed to far outpace the cost of the portfolio. An examination of the 41 innovations that DIV supported in its first 2-1/2 years revealed that these

innovations reached around 100 million people with a total spending of $16 million. However, the distribution of the impacts was skewed, with 9 of the 41 innovations accounting for 98 percent of the people reached by innovations in the portfolio and “almost certainly generating the vast majority of the portfolio’s social return,” she said, adding “That’s actually quite typical when you’re supporting innovation.”

A lower-bound estimate of the benefits of DIV investments was obtained by looking at just five innovations from this early portfolio. It showed that for a portfolio investment of $16 million, innovations supported by DIV generated an estimated $261 million in discounted social benefits, a cost-benefit ratio of 17 to 1. Gallant noted, “This analysis showed that open, tiered, evidence-based innovation funding with a rules-based, peer-review-driven decision process has the potential to deliver exceptionally high social returns.”

Regarding which innovations scale, a common view is that pilots rarely scale and that later-stage innovations have a much higher scaling rate. The latter point is true, said Gallant, in that pilot grants are less likely to scale than testing and scaling grants. But because they were so much less expensive, pilots actually reached more people per dollar spent than later-stage awards. “It can be inexpensive to try out new, high-potential but perhaps higher-risk ideas, and when they work out they can be enormously impactful,” she explained.

Low costs are important in scaling up, said Gallant. Innovations are much more likely to scale if they cost less than $3. Also, innovations that leverage the distribution of an established entity, particularly governments or large-scale nongovernmental organizations or businesses, were three times more likely to scale than those that tried to set up their own distribution networks. Interestingly, she added, innovations that had previous rigorous evidence of impact or involvement with an economics researcher were much more likely to scale, perhaps because researchers choose which innovations to be involved with based in part on preexisting likelihood of success. “Whatever it is, our findings call into question the conventional wisdom of a trade-off between rigorous evaluation and scale,” Gallant continued. “There’s often a feeling that doing a lot of testing or an RCT slows things down and interferes with the fast-moving process of innovation. But we saw that applicants who had previously done an RCT or ran rigorous research as part of their operational process were much more likely to achieve sustained scale.”

These results raise the question of why private investors do not act when the social returns are so high. One hypothesis is that commercial investors leave arbitrage opportunities for socially minded investors when the expected private returns are low but the social returns are high. Gallant explained, “This has implications for where government might invest, and it presents a possible strategy that philanthropic or government funders might consider.”

As other government agencies think about how to integrate experimentation and innovation into their work, the challenges DIV has faced and continues to face are important to keep in mind, she said. DIV is a catalytic innovation fund, not an operational funder. As such, its work is not to

independently scale innovations but to identify, help develop, and pressure test innovations to find highly scalable, cost-effective solutions that operational funders can embrace. “Bringing innovation to scale in government agencies is hard,” said Gallant. For an innovation to affect large-scale programming, institutions need a system by which to determine what to bring to scale and processes to incorporate new ways of doing things into large-scale and longstanding procedures and programs. DIV provides a model and a process to help determine what works. Obstacles include constrained and hypertargeted funding, limited funding mechanisms, insufficient time, limited manpower, and a broad mix of incentives that make it hard to integrate what works into standard practice.

DIV recently received a $45 million award from Open Philanthropy to help it build the infrastructure needed to connect innovation and experimentation to large-scale operational programming. Gallant explained: “With this, we’re hoping to find and leverage ways to lay a blueprint that will facilitate the widespread uptake of promising interventions from this portfolio and from other literature across USAID. We’re putting money on the table, hoping to leverage funds from DIV to bring in significant funding from other parts of the agency to help bring highly promising solutions to scale.”

In this way, DIV hopes to generate even greater social returns across the agency with a relatively small up-front investment. “We want to make sure that the big dollars that USAID is moving toward development programs are spent in the best ways possible to meaningfully and measurably improve people’s lives,” said Gallant.

The DIV model has been replicated, both outside of government, through such institutions as the Global Innovation Fund, and inside of governments, including in Korea and France. However, Gallant explained, DIV has the advantage of sitting within USAID, where other divisions can support efforts to develop and integrate evidence and experimentation across the agency’s wider programming. DIV also benefits from extensive peer review and can share feedback with rejected applicants to help them come back stronger. However, despite a substantial number of innovations from the portfolio reaching millions of people, DIV still has not seen large-scale uptake of promising investments from its portfolio throughout USAID. DIV “is far from perfect,” Gallant reported, “but it is a tool that could inspire other tools to integrate research and innovation while right-sizing risk, as we collectively try to maximize social value.”

The initial investment for a department or an agency can be quite small. Many received grants of less than $200,000, and DIV itself was established with just $1 million. Gallant cautioned, “We shouldn’t expect perfection. We think part of success has been a philosophy of continuously iterating and continuously learning.” She said that staff members at DIV are happy to speak with U.S. government and other colleagues interested in learning more about this kind of work. They also want to learn from others to improve their own approaches.

In response to a question about the high rates of return demonstrated by DIV-supported projects, Gallant noted that deep-dive rate-of-return analyses have been done on only a few projects. Such analyses are very time intensive, and they

are subject to other constraints, such as tracking impacts beyond the period of an award and figuring out how to monetize gains and capture reach.

When asked about how proposals are evaluated at DIV, Gallant replied that the program uses a broad range of reviewers, including USAID colleagues, country-level feedback, and technical feedback. It also works with academics who are oriented toward policy and know what it means to work with government or bring programs to scale. “If somebody’s entire path to scale is reliant on last-mile distribution, we talk to somebody who’s doing last-mile distribution in that area,” she said. Such reviewers “tend to bring perspectives that others might not.”

DIV’s success rate for funding is only about 2–3 percent, “which I’m not thrilled about,” said Gallant. DIV tries to be very explicit about what it is looking for so that it does not waste people’s time. It also provides feedback throughout the process, such as recommending the downscoping of a project (or, sometimes, upscoping). For due diligence, the review process tends to take 2–5 months after an initial review, with ongoing questions and answers with the applicants. The questions being asked depend on the stage of the application, the amount being requested, and other factors. Gallant said that DIV tries to make funding decisions in less than a year, “and hopefully closer to that 8- or 10-month mark.” DIV may say it is only able to fund part of a proposed project. It also seeks to match researchers with other academics and researchers. “We get a lot of proposals from innovators who are putting forward a really interesting and compelling solution but might not have the technical skills to rigorously test it,” Gallant explained. Sometimes even the reviewers want to engage with a proposed project.

Finally, in response to a question about how the DIV model might be replicated, Gallant observed that time and investments need to be made at different levels of an institution to learn how evidence-minded programming can be integrated. The key players and their motivations need to be identified, and activity design and decision making need to be examined.

This page intentionally left blank.