Experimental Approaches to Improving Research Funding Programs: Proceedings of a Workshop (2024)

Chapter: 6 Structuring Support for Experimentation in Government

6

Structuring Support for Experimentation in Government

The fifth panel of the symposium looked at how support can be structured for people in government to both experiment and apply their findings. All three of the organizations represented on the panel, said moderator Dylan Matthews (Future Project), have direct experience with the issue, in that they have been connecting scientists and researchers on the outside of government with people on the inside.

FOSTERING AN INTERDISCIPLINARY EFFORT

The creation of innovative science policy is a classic interdisciplinary effort in which all parties benefit from a flow of ideas, people, and conversations across economics, policy, academia, industry, science, and government, said Jordan Dworkin (Federation of American Scientists [FAS]). But, like many interdisciplinary efforts, it is not incentivized by any of those individual parties.

FAS works across domains to provide incentives, motivation, and support for people to engage in such efforts, using three levers. The first lever is policy entrepreneurship through the identification and crowdsourcing of ideas and solutions from outside experts. Experts can be from academia, industry, or the nonprofit sector; all have thought deeply about issues relevant to science policy and policymakers and can deliver ideas to those in the science policy community. The second lever is sourcing, training, and placing outside science and technology talent into the policy ecosystem. The Impact Fellowship model, which FAS has been championing, has had considerable success in working with government agencies to identify their needs and recruit people who can meet those needs.1 The third lever is direct agency partnerships to shape government agendas and activate the science and technology ecosystem in response to policy and legislative priorities. FAS tries to coordinate actors across government and support the implementation of different models.

___________________

1 More information about the fellowship is available at https://fas.org/impact-fellowship

Dworkin provided more detail about the fellowships FAS has organized, which in 2022 placed 43 fellows across 11 federal agencies. Fellows are intended to be a short-term boost to capacity and talent, but they are also intended to inspire longer-term investments in the science and technology skills sets and expertise they bring. Dworkin suggested that a number of the offices in which these short-term fellows worked went on to hire longer-term experts in the same roles.

FAS has found that interdisciplinary collaboration can help build capacity and motivation for experimentation, as well as produce science policy in a domain area, Dworkin explained. It has contributed to the establishment of an interagency working group to think through the obstacles to and opportunities for experimentation. It has also brought in external people to champion and lead on these efforts, and it is exploring the possibility of placing Impact Fellows in positions where they could be involved in experimentation directly.

A major focus of policy entrepreneurship has been exploring ideas to build out the structural diversity of the science and technology ecosystem, he said. For example, FAS has been involved in supporting innovative institutional designs and funding models across government, with a particular focus on testing a wider range of portfolios and funding systems. “Successfully running any of these plays is going to require a lot of support” from inside and outside government.

Dworkin had recently joined FAS after working in biomedical science, and he spent the last few minutes of his presentation talking about how to structure scientific support for experimentation outside government. He said that “there is a pretty serious lack of buy-in from a lot of leaders in the scientific community. And that’s a critical obstacle, because if there’s no political support and no scientific support for people to take on these efforts, there’s no incentive to spend the time or the money or the social capital to try to implement them.” Building internal political support and external scientific support in parallel is a key goal for FAS, which “will make everyone’s efforts to pursue these experimental designs easier,” he said. People who have risen through the ranks of science tend to be good at responding to incentives in the research enterprise, and they generally have few reasons to change those incentives, he explained. To overcome this resistance, he urged building a community of earlier-career researchers who want to contribute to experimentation and reform. For example, he credited the National Institutes of Health with a recent effort to support postdoctoral fellows engaging in the policy process, which will help build grassroots support.

“We as a community have a great opportunity to reintroduce voice and contribution and collaboration as meaningful opportunities and options for those who are interested in the kinds of things we’re pursuing,” Dworkin concluded. “Opening up data for these questions, opening up collaborations, opening up fellowships, doing outreach to universities, and thinking more creatively about how they can engage in science policy is a promising opportunity for helping to structure external support while also building new mechanisms for structuring internal political support.”

THE EVIDENCE ACT

Diana Epstein (Office of Management and Budget [OMB]) described recent activities within the federal government to build the infrastructure to support a culture of experimentation and evidence-based policymaking.

The Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act (Evidence Act, P.L. 115-435), signed by President Trump in January 2019, includes three titles: (1) Federal Evidence-Building Activities, (2) Open Government Data Act, and (3) Confidential Information Protection and Statistical Efficiency. The Evidence Act has offered opportunities to reduce silos and build relationships across agency functions; build peer networks within and across councils; plan for evidence-building strategically; elevate program evaluation, statistical capacity, and data infrastructure as mission-critical functions across all agencies; and be much more transparent about agencies’ evidence-building priorities. “Federal agencies have been doing good work in the evidence and data space for many decades,” Epstein said. “But this created a paradigm shift for agencies to think about using data and building evidence more strategically.”

The act focuses on leadership with the creation of three new senior officials responsible for meeting the act’s requirements: evaluation officer, chief data officer, and statistical official. It also emphasizes collaboration and coordination, reflecting the understanding that people within and across agencies have to work together to achieve the goals of the law. It calls on agencies to strategically and methodically build evidence instead of pursuing ad hoc efforts, and it elevates program evaluation as a key agency function.

Since the law came into effect, Epstein continued, agencies have designated evaluation officers, statistical officials, and chief data officers, and these officials are networked through interagency councils that meet every month. Agencies have published evidence-building plans and policies, including the multiyear learning agendas required by the law; annual evaluation plans; and analyses of their capacity to do research, evaluation, statistics, and other forms of analysis. Documents are posted on agency websites and are linked centrally at the website evaluation.gov.

The Biden administration reinforced the Evidence Act through a presidential memorandum on restoring trust in government through scientific integrity and evidence-based policymaking, which stated that “scientific and technological information, data, and evidence are central to the development and iterative improvement of sound policies, and to the delivery of equitable programs, across every area of government.” OMB also released guidance that integrates, clarifies, and enhances prior guidance on these topics; reiterates the expectation that agencies use evidence whenever possible to further both mission and operations and build evidence where it is lacking; and emphasizes the importance of building a culture of evidence to improve decision making. “This should not be an activity that’s happening over here in the research office on the side, people doing their own thing and producing nice reports that sit on shelves. Rather, evidence has to infuse the culture. It has to be everyone’s job.”

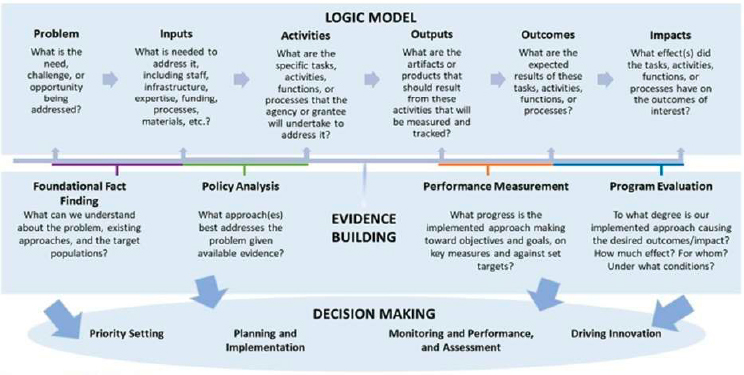

SOURCE: Presentation by Diana Epstein.

While planning is necessary, implementation is the key step, said Epstein. To help in this process, OMB has prepared a model designed to promote a culture of evidence: see Figure 6-1. The model shows that evidence is generated in a variety of ways and takes a variety of forms, but evidence should inform decision making at all stages of the process, whether setting priorities, implementing, monitoring, or experimenting. Epstein stated, “We hope that everyone within a federal agency can find themselves somewhere here and see that evidence should be part of their job, and that integrating an evidence-based mindset into their work will help them do their job better.”

The Evidence Act created new statutory systems for program evaluation, adding to existing systems. In response, Epstein explained, OMB issued guidance on evaluation standards and practices that articulates five standards—relevance and utility, rigor, independence and objectivity, transparency, and ethics—that agencies must apply to all evaluation activities. The guidance should be implemented by evaluation officers, agency evaluators, and staff in related functions; it also includes ten leading practices that can support implementation of the standards.

Agencies have been very honest in describing their gaps in capacity, Epstein said. “They were willing to put it out transparently that they need to do better in these areas. That’s a little-known story of the Evidence Act’s implementation, but I think it is an important one. And there’s probably a lesson in there that we can apply toward other things.” She noted that she has just a four-person core team at OMB, so “it is incumbent upon the agencies to make sure that they are adhering to their evaluation policies, and that they are raising the bar themselves. This has to be a joint enterprise.”

Evaluation.gov includes the learning agendas, annual evaluation plans, and resources associated with that body of work, Epstein pointed out. A dashboard

of agencies’ learning agenda questions coded by agency and thematic area is also available, which is designed in part to facilitate additional collaboration and partnership.

“This is hard work,” said Epstein. “This is a major culture change within a very large bureaucracy,” and the law did not include new appropriations to fund its provisions. Nevertheless, the agencies individually and together have made great progress, she said. She also encouraged others to get involved in the effort. “We’re hoping to build out an evidence project portal interface where agencies can post questions [and indicate where] they are interested in building collaborations, and those on the outside can find those questions and where the opportunities exist.”

In response to a question, Epstein observed that not all agencies have a culture of innovation and research. It is often useful to view evaluation through a learning and improvement lens rather than an accountability lens, since an accountability frame can generate fears that programs are going to be cut because of poor results. Trying to shift people’s thinking away from fear toward an embrace of learning and needing improvement can be helpful. Epstein asked, “If you do this, don’t you want to know how to do it as best possible to serve the American people as effectively and efficiently as you can?”

EXPERIMENTING WITH CHANGE AT THE INTERNAL REVENUE SERVICE

Dayanand Manoli (Georgetown University) described working with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) on a project that involved simplifying notices to encourage individuals to claim Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) benefits. Working through the 1971 Intergovernmental Personnel Act (IPA, P.L. 91-648), which temporarily assigns workers to tasks across governmental boundaries, Manoli and his colleagues randomly selected some individuals to receive simplified notices while others received unchanged, baseline notices. The simplified notices had higher response rates and led to increased tax compliance in terms of individuals claiming EITC benefits.

The results of this experiment had effects that have percolated throughout the taxpayer experience, Manoli said. They have also helped build a culture of evidence and the translation of evidence into policy. “Oftentimes, as an academic, we might do a certain study and the results are put on the shelf. But this was taking the results and putting them into practice.”

Changes from the results of that experiment happened quickly. The project started in 2009 and results were available in 2010 and fed into communications involving the next tax season. But publication of a paper describing the results in an economic journal took another 5 years.2 “The notices

___________________

2 Bhargava, S., and D. Manoli. 2015. Psychological frictions and the incomplete take-up of social benefits: Evidence from an IRS field experiment. American Economic Review 105(11):3489-3529. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20121493

were redesigned and implemented as national policy before the paper was published,” reported Manoli.

Manoli also worked on a project that involved identifying nonfilers who have income information reported to the IRS but do not claim benefits or file tax returns. Again, a simple reminder was generated that said, in essence, “If you haven’t done so, please file your tax return.” “That simple reminder carried a lot of weight,” Manoli observed. “We saw increases in tax filing and EITC participation, as well as actually paying taxes that were owed to the IRS. Again, that culture of experimentation . . . and then using it to move policy forward was crucial.”

As an academic researcher, Manoli knew the peer-review and publication process well, but the IRS also recognizes the importance of peer review and publication, he said. External feedback from peer reviewers has driven scientific innovation, implementation, and policy building at the agency, and the IRS is now collaborating with other academic researchers on the customer experience, tax compliance, and audits.

Through the IPA, Manoli, who had previously worked with the Volunteer Income Tax Assistance program, was allowed to work at the IRS as if he were an employee. He was able not only to handle confidential data, but also to collaborate with people who think about tax administration day in and day out. These are the people with the institutional and procedural knowledge to build experimentation and implementation, “and that’s where these synergies take place,” Manoli said. Working with the IRS was “an opportunity to work with an agency that touches every individual with reported income in the United States. To think about affecting policy through a notice that is sent out or information that is put out by the Treasury Department or the IRS was fantastic.”

Asked about the constraints imposed on such efforts, Manoli emphasized the number of things on the agenda of typical federal employees and the demands involved in asking them to take on additional tasks. Even a worker who transferred via the IPA requires project management, including creating the position, onboarding, and training in office procedures.

Manoli concluded by emphasizing that a culture of research and evidence already existed within the IRS. The agency interacts with taxpayers extensively, and a feedback loop already existed to simplify the language used in those interactions. “I don’t know that any of this is possible without that culture,” he said.

PANEL DISCUSSION

In response to a question for the panelists about who can get involved in programs involving experimentation at federal agencies, Epstein said there is no one ideal role for outside individuals or groups. Roles can range from workers transferred through the IPA to extended collaborations to serving on technical review panels. “We don’t want to assume that there’s just one best path,” she said. Outside groups bring energy, enthusiasm, expertise, and technical know-how to

the table. Federal employees are busy and want to do the best job they can. Epstein observed, “It can be really powerful to have someone come in from the outside who has the time and the mental headspace to focus on a particular project. . . . New ideas and new perspectives can expand our range of thinking.”

Outside involvement also provides momentum and opportunities to experiment, said Dworkin. This experimentation can challenge existing and baked-in processes, and legislation can further enhance structural diversity.

To get involved in government experimentation, Manoli recommended learning about the constraints federal employees face in working with others. “It’s not that they don’t want to take on projects, but they’re just limited in bandwidth.” A comprehensive resource covering the different pathways that researchers at universities or think tanks could take to collaborate with government agencies would be extremely valuable, Epstein added, offering as an example a toolkit that agencies could use to leverage outside help through the IPA. Each agency has some idiosyncrasies, but some cross-cutting pathways are broadly applicable. Working to do something new for the first time can be difficult and time consuming, but broadly applicable lessons can be drawn from examples of successful collaborations done in different places.

In response to a question, Manoli also observed that student internship opportunities are crucial. For example, both the IRS and the Treasury Department have internship programs, although they are not widely known. The Presidential Management Fellows Program is another opportunity for students to be matched with agencies. Advertising such programs and spreading information by word of mouth can help alert more people to their existence.

On this topic, Epstein pointed to the paid internships available through the Executive Office of the President: “If you have someone, we’d love to host them as an intern.” She got her start as an intern at a federal agency and then used a data set from that agency for her doctoral research. Some agencies are also experimenting with ways of getting students and scholars involved, such as the summer data challenge posed by the Department of Labor to use existing data to answer specific research questions. Similarly, a new Analytics for Equity pilot is a partnership among federal agencies and the National Science Foundation to provide small grants for projects aligned with agencies’ equity-focused learning agendas.3 “Those seem like great opportunities for students to get a foot in the door,” Epstein stated.

A question about providing information—in part to counter disinformation—led Dworkin to comment on the need for an evidence ecosystem that is more accessible and understandable. The information people need is often so decentralized, and is often available in forms that seem authoritative, that people do not know where to turn for accurate and timely information. FAS has been working with partners to advance rigorous and up-to-date evidence synthesis

___________________

3 For more information, see https://www.whitehouse.gov/ostp/news-updates/2022/04/07/fact-sheet-biden-harris-administration-launches-year-of-evidence-for-action-to-fortify-and-expand-evidencebased-policymaking

in key areas of policy and health so people can access knowledge more seamlessly and so that it can be read and understood by broader audiences than is the case for scientific articles.

Epstein praised the practice of condensing large reports to executive summaries that are written in plain language and, beyond that, to two-page policy briefs that highlight the key findings for a policymaking audience. “This is not being done everywhere,” she observed, “but I have seen a very marked shift in the last few years toward producing information that is more understandable and digestible while also not oversimplifying to the point of losing the important nuance in the findings.”

Manoli emphasized the importance of understanding the information system. For example, the IRS puts out guidance each year on tax information, in part to deal with the myths that surround taxes. He stated, “This evidence-building machinery allows you to better understand misinformation, as well as providing transparent, high-quality information.”

A question was also asked about how professional societies can help acquire reliable data without facing the same constraints that a federal evaluation might. It is a hard problem, Dworkin acknowledged, particularly in trying to move beyond bibliometric data into outcomes data. Some academics and nonprofits have taken up survey work. The Federal Demonstration Partnership, for example, has engaged in large-scale university surveys and has collected rich information about people’s experience with administrative burden, for example. But the infrastructure needed to collect that kind of information is not discussed enough, he said, and both public and private support need to be marshalled to build it.

In response to a question about how collaborators can compensate for federal staffing shortages, Dworkin said that FAS is eager to support agencies with shortages in finding fellows or external collaborators who can help pursue evaluations or experiments. Philanthropies are also willing and able to support some personnel transfers, he said, as are the people involved in those transfers—many of whom could make more money in other pursuits but are eager to take on a mission that they think is important and valuable. “Not every open role that is needed in these agencies is going to be able to be funded in this way,” Dworkin continued, “but generally there is a ton of support. External partners and external experts are willing and ready.”

Epstein noted that supplemental materials in the president’s fiscal year 2024 budget proposed investments to build capacity in agencies where it is lacking. These are “small proposals,” she said, “but we think small proposals can make a big difference. We focused in the president’s budget on building that capacity and trying to make the case for some of these positions.”

Manoli was also optimistic, although he said the IPA is not a long-term solution because of the project management and other costs involved. But evaluation officers and organizations now exist within government agencies that are behind the effort to supplement existing staff.

On this topic, Epstein mentioned an article she wrote with two coauthors on the federal evaluator workforce.4 It addressed basic questions: Who are these people? What do they do? How can researchers work with them? She said, “Our goal was to open up that black box to public audiences and try to illuminate who federal evaluators are. They’re an amazingly diverse group of folks who have a lot of important jobs in shepherding the evaluation enterprise.” They do everything from scoping research questions, working with programs to identify priorities, developing preliminary thoughts for design, and navigating the administrative process. “It is an incredibly complex job to even get an evaluation launched,” stated Epstein

“The most important thing to keep in mind is that these folks do exist,” Epstein said. “If you’re someone who wants to partner with a federal agency, get to know these people. It’s really important to know the program staff, and the federal evaluators are going to be your friends.” OMB has tried to get evaluators networked with each other so that they have a professional community within the federal government. “We want to give these folks opportunities to get to know each other and to support each other.”

In response to a question from moderator Matthews about how to integrate evidence drawn from separate studies—in effect, doing a meta-evaluation of evaluation—Manoli noted that different projects have different structures and personnel. But they are all part of a much broader learning agenda to “figure out what works best when.” Creating a network of people involved in evaluations would be a way to exchange information about successes, barriers, strategies, data generation and protection, and other issues that arise. This process would resemble a natural experiment much more than a randomized controlled trial, but Manoli said it is still likely to be “really helpful.”

Eva Guinan (Harvard Medical School), who had spoken earlier in the workshop, raised the issue of validating data collection instruments, based on her own experience with the problems encountered when using the World Management Survey with faculty members, who respond “in very individualized ways.” Manoli responded to this issue by pointing out the possibility of using administrative data, which generally does go through checks and validations as part of compliance measures. Peer review and other forms of scientific assessment can also provide feedback on whether a survey instrument, for example, is valid or not, and cognitive testing is a normal procedure in developing surveys, said Epstein.

___________________

4 Epstein, D., E. Zielewski, and E. Liliedahl. 2022. Evaluation policy and the federal workforce. New Directions for Evaluation Spring:85-100. https://doi.org/10.1002/ev.20487

This page intentionally left blank.