Homelessness: A Guide for Public Transportation (2024)

Chapter: Chapter 2 - Homelessness Basics

CHAPTER 2

Homelessness Basics

As more people live outside, discussions about homelessness appear in news stories, on social media, and at neighborhood association meetings. Yet what constitutes and causes homelessness is not well understood by the public. In this chapter, definitions, causes, and demographics of homelessness are described. Stereotypes about people experiencing homelessness are discussed. The chapter concludes with a discussion on the impacts of homelessness on public transportation.

2.1 Definitions and Types of Homelessness

There are two principal federal definitions of homelessness used by HUD and the U.S. Department of Education (ED).

2.1.1 HUD’s Definition of Homelessness

HUD identifies four categories of homelessness to determine whether someone is eligible for federally funded homeless services:

- Literally homeless,

- Imminent risk of homelessness,

- Youth under 25 or families with children who are defined as homeless under other federal statutes, and

- People escaping domestic violence (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development n.d.a).

People categorized as “literally homeless” are living in a place not intended for human habitation; living in a shelter, temporary housing, or transitional housing; or will be leaving an institution such as prison or psychiatric care and were homeless prior to institutional entry (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development n.d.b). A more detailed description of HUD’s categories of homelessness is included in Appendix A.

In addition to these four categories, HUD further classifies people as experiencing chronic homelessness as well as sheltered and unsheltered homelessness:

- Chronically homeless. To be considered chronically homeless, a person must have a disability, fit HUD’s definition of “literally homeless,” and have been homeless for at least 1 year or homeless at least four times in the last 3 years for a total of 12 months or longer (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development 2015; U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development n.d.d). Disabling conditions include mental illness, substance use disorders, and physical disabilities. A point-in-time count in 2020 found that 20% of adults in shelters were chronically homeless (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development 2022b, p. 1–6), that seven in 10 people experiencing chronic homelessness identified as male (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development 2022b, p. A-8), and that 66% of people classified as chronically homeless were living someplace not meant for human habitation (U.S. Department of Housing and

- Urban Development 2021a, p. 64). Other types of homelessness based on duration or frequency of homelessness include episodically homeless (occasionally homeless) and transitionally homeless (temporarily homeless) (Kuhn and Culhane 1998).

- Sheltered versus unsheltered. Within the HUD definition of homelessness, people who are “literally homeless” are classified as living “sheltered” or “unsheltered.” People are sheltered if they are staying in an emergency shelter, motel, or transitional housing. People are unsheltered if they are sleeping outside, on public property or assets, in a recreational vehicle (RV) or car, in an abandoned building, or in other places not meant for human habitation (Batko et al. 2020a).

2.1.2 ED’s Definition of Homelessness

ED includes the HUD definitional categories and classifications. ED also includes unaccompanied children and youth in public schools—preschool through 12th grade—who are living “doubled-up” (U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness 2018). “Doubled-up” refers to unaccompanied youth or families with school-aged children living with another household for economic or safety reasons (National Center for Homeless Education 2021a, p. 13). Doubled-up families or unaccompanied youth may look different from household to household: a whole family may share a single bedroom and the previous occupant of that bedroom may now share a room with other family members, or a young person may be sleeping on a couch. Adults without children in school would not be reflected in ED data about homelessness.

2.1.3 Definition of Homelessness Used in This Report

This report uses the ED’s expanded definition of homelessness that includes youth and their families experiencing homelessness who are doubled-up. Defining homelessness more broadly allows this report to consider a wider range of responses to homelessness and place those responses within the full context of homelessness.

2.1.4 Focus Population for This Report: Unsheltered Homeless

While this report relies on the ED’s definition of homelessness, opportunities for transit agencies to respond to unsheltered homelessness receive more attention in the report. Transit agencies are currently challenged by people living or seeking temporary shelter in or on their properties.

2.2 Homelessness in the United States and Its Causes

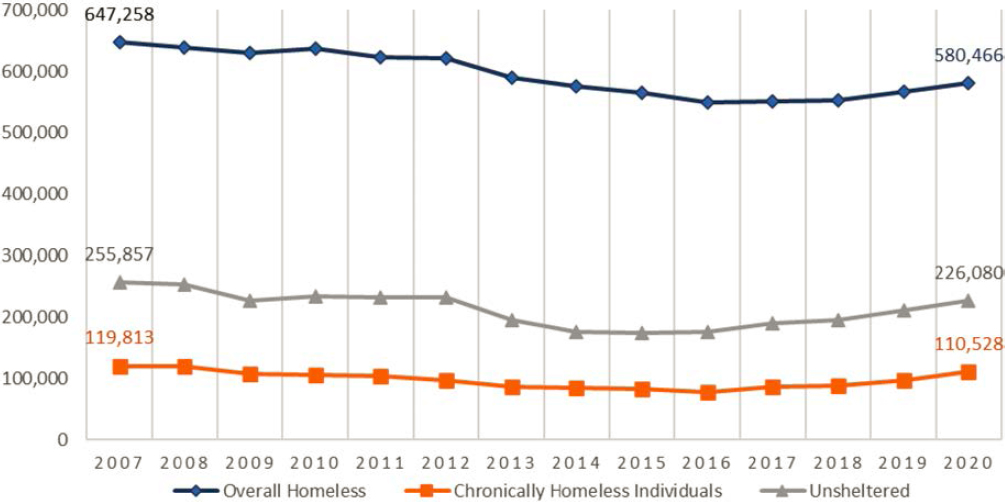

In 2016, the United States experienced the fewest number of people experiencing homelessness (547,928) since the high in 2007, where almost 650,000 people experienced homelessness in a given night (Henry et al. 2021). After years of reductions in the numbers of people experiencing homelessness, in 2017 the number began to increase, countering nearly a decade of progress of steady declines in the number of people experiencing homelessness on a single night (Henry et al. 2021). Particularly concerning is the steady increase on unsheltered individuals, as shown in Figure 1. By 2020, the number of people experiencing homelessness had grown to 580,466 (Henry et al. 2021). Figure 1 provides a visualization of the number of people experiencing homelessness in the United States between 2007 and 2020 (National Alliance to End Homelessness n.d.).

Since 2019, homelessness in the United States has increased by 2%; it had primarily been on the decline from 2007 to 2017. Unsheltered homelessness grew 7% nationally between 2019 and 2020 (Henry et al. 2021). In 2020, of the people experiencing homelessness, 39% lived unsheltered, with the rest living in emergency shelters or transitional housing (U.S. Department of

Figure 1. Homelessness national counts from 2007 to 2020.

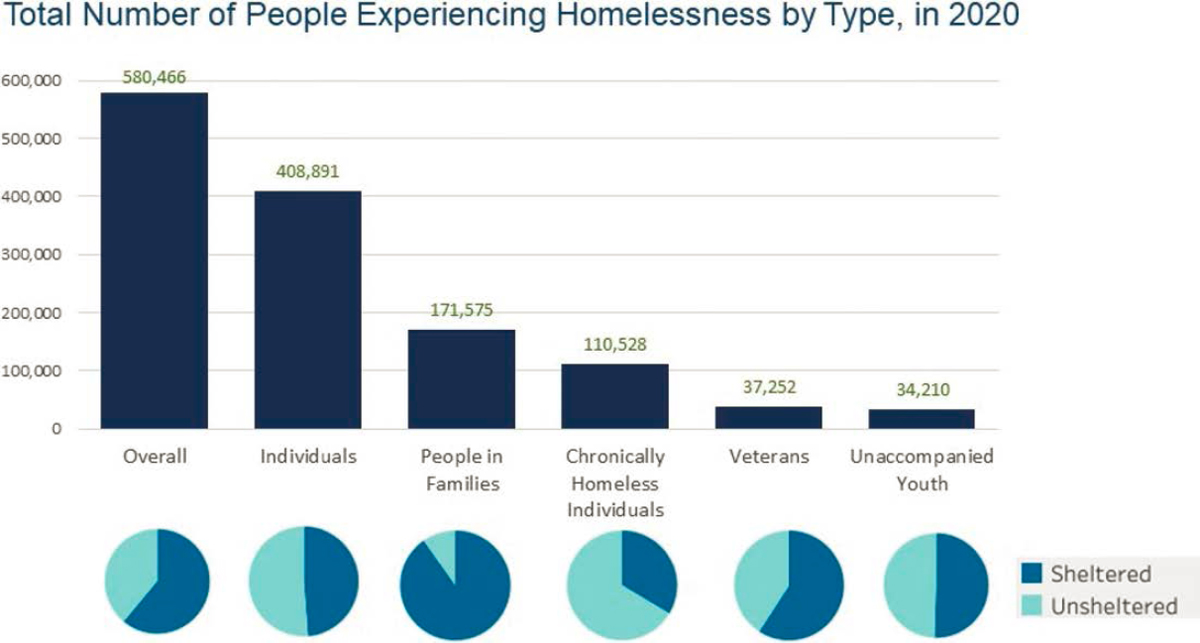

Housing and Urban Development 2021a). The growth of unsheltered homeless populations means that even more people slept on sidewalks, in tents, or in cars, or called transit stations or facilities “home.” States throughout the West had the highest rates of unsheltered homelessness, and California alone accounted for 51% of all the people experiencing unsheltered homelessness nationwide (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development 2021a). Figure 2 shows the number of people experiencing homelessness in 2020 demographically and by whether they were sheltered or unsheltered (National Alliance to End Homelessness n.d.).

Homelessness is a complex societal problem, caused in part by an inadequate safety net in the United States that affects food, health, income, and housing security. Insufficient income and lack of affordable housing are the leading causes of homelessness. According to the most recent annual survey by the U.S. Conference of Mayors, major cities across the country report that the top causes of homelessness among families were (1) lack of affordable housing, (2) unemployment, (3) poverty, and (4) low wages, in that order (U.S. Conference of Mayors 2017). The United States has a shortage of 7 million rental homes affordable and available to those with “extremely low incomes,” as classified by HUD, whose household incomes are at or below the poverty line, or 30% of their area median income. Extremely low-income renters face a shortage of affordable and available rental homes in every state and major metropolitan area. Among the 50 largest metropolitan areas in the United States, the supply ranges from 13 to 50 affordable and available rental homes for every 100 extremely low-income renter households (National Low Income Housing Coalition 2022b).

The number of people experiencing homelessness in the United States has been increasing in places with affordable housing crises (National Low Income Housing Coalition 2022a; 2022b). There is growing evidence that housing market conditions, such as the availability and cost of rental housing, have much more influence on the prevalence of homelessness than factors traditionally believed to have, such as poverty, drug use, mental illness, weather, and the amount of public assistance (Colburn and Aldern 2022). In many cases, the state of homelessness of an individual is not caused by one specific factor but rather several of these compounding factors.

While people have been experiencing homelessness throughout history, most recent narratives focus on what is described as the “contemporary” era of homelessness. Beginning in the

Figure 2. Selected demographics of people experiencing homelessness and their sheltered status.

late 1970s and early 1980s, the number of people experiencing homelessness grew significantly (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2018). Driven by large reductions of federal funding for affordable housing and a recession, people with lower incomes faced additional challenges to accessing and staying in safe housing (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2018). At the same time, a federal rollback in social service funding, coupled with criticisms of treatment at psychiatric hospitals, led to the closure of mental health facilities nationwide. Funding to support community-based mental health support and housing did not follow (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2018). Furthermore, the “war on drugs” disproportionately targeted people of color, leading to higher rates of incarceration and felony convictions that, in turn, made accessing housing more difficult (Jensen et al. 2004).

What this means today is that a lack of affordable housing in a region drives homelessness rates (Colburn and Aldern 2022; Glynn and Fox 2019; Honig and Filer 1993). One study (Nisar et al. 2019) calculated the homelessness rate in areas with “tight, high-cost markets” as 37 per 10,000 people, while the rate in places with more affordable housing markets was 11.4 to 10,000 people, a 69% decrease. In areas with high rents and tight (low-vacancy) housing markets, homelessness rates increase.

For public transportation agencies in areas experiencing a growth in unsheltered homelessness, housing market forces likely explain the changes they are witnessing. In low-vacancy, high-cost rental markets, people may work full time and still find an apartment out of reach financially. According to the National Low-Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC) as of 2022:

Thirty states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and over 50 counties and municipalities now have minimum wages higher than the federal minimum wage, but even taking into account higher state and county minimum wages, the average minimum-wage worker must work 96 hours per week (nearly two

and a half full-time jobs) to afford a two-bedroom rental home, or 79 hours per week (two full-time jobs) to afford a one-bedroom rental home at the fair market rent. (National Low Income Housing Coalition 2022b, p. 1)

For transit agencies in locations where unsheltered homeless populations are stable or shrinking, monitoring vacancy rates and rent costs can help alert the transit agencies to a potential growth in the number of people experiencing unsheltered homelessness.

2.3 Demographics of People Experiencing Homelessness

Rates of homelessness vary across sociodemographic groups. People with lower incomes will be less likely to avoid homelessness in the event of a major life disruption such as a job loss. Natural disasters can render people homeless for short or longer periods of time (National Coalition for the Homeless 2009). People with disabilities may experience discrimination in employment opportunities, and accessing social security may take considerable effort (Smalligan and Boyens 2019).

2.3.1 People of Color

People of color experience higher rates of homelessness than white community members.

- Black or African American people made up 39% of those experiencing homelessness nationwide in 2020, but were only 12% of the overall population (Henry et al. 2021; Olivet et al. 2021).

- Indigenous people (American Indian, Alaska Native, Pacific Islander, Native Hawaiian) made up 5% of those experiencing homelessness but around 1% of the overall population (Henry et al. 2021).

- Asian and Pacific Islander subpopulations may be experiencing homelessness at higher rates than an aggregate number of the summary Asian and Pacific Islander category indicates (Moses n.d.).

- Latinos of any race made up 23% of those experiencing homelessness, but only 16% of the overall population (Henry et al. 2021).

2.3.2 Age

In 2020, HUD estimated that 34,000 people under the age of 25 experienced “unaccompanied homelessness” (without a parent or guardian present) in the United States; this includes runaway youth (Henry et al. 2021). Using the broader definition of homelessness that includes children living “doubled-up,” the ED estimated that 1,280,866 students experienced homelessness in the United States during the 2019–2020 school year (National Center for Homeless Education 2021b). Racial disparities are greater among unaccompanied youth than among adults experiencing homelessness (Henry et al. 2021). In 2017, adults over 50 made up nearly 34% of those experiencing homelessness, a 10% increase over the previous decade (Henry et al. 2018). Homelessness among older adults was expected to continue rising, with one article forecasting that it would triple between 2015 and 2030 in several large cities (Culhane et al. 2019).

2.3.3 Gender and Sexual Orientation

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning, intersex, asexual, and more (LGBTQIA+) individuals experience homelessness at disproportionately high rates. Surveys show that approximately 8% of transgender adults and 3% of genderqueer sexual minorities

experienced some form of homelessness in the previous 12 months, compared with only 1% of cisgender, heterosexual adults (Wilson and Choi 2020). LGBTQIA+ youth also experience disproportionately high rates of homelessness: in a representative national sample, LGBTQIA+ youth made up more than 21% of all those ages 13 to 25 experiencing homelessness (Morton et al. 2018).

2.3.4 Disabilities

In 2020, about 21% of people experiencing homelessness had a severe mental illness, and 17% lived with substance use disorders (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development 2020b). Substance use disorders and mental illness can co-occur with each other or with chronic health conditions or physical disabilities (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2021). In 2020, people experiencing chronic homelessness and who had one or more disabling conditions made up about 25% of the total population of people experiencing homelessness (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development 2021a). Compared to a 39% overall rate of unsheltered homelessness, 66% of those experiencing chronic homelessness were unsheltered (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development 2021a). Increases in chronic, unsheltered homelessness has driven the increased homelessness rates in recent years (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development 2021a). People experiencing homelessness may also have physical disabilities, not just mental health disorders. In one analysis of homelessness in Los Angeles, 19% of people experiencing homelessness reported physical disabilities (Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority 2020; Los Angeles Almanac 2022). That number grew to 43% for the chronically homeless population.

2.4 Homelessness, Mental Illness, and Substance Use Disorders

Behavioral health challenges related to mental health or substance use are not a primary reason for homelessness. Estimates indicate that at least 30% of persons experiencing homelessness suffer from serious mental illness, and that approximately 50% have a substance use disorder (alcohol or drugs), with many suffering from both conditions (Lebrun-Harris et al. 2013). The compounding impact of substance use disorders, mental illness, unstable housing, unemployment, and poverty worsens chronic and episodic diseases, making the management of these diseases more difficult (Lebrun-Harris et al. 2013). An individual’s mental health condition or substance use disorder may make it harder to do activities necessary for obtaining or maintaining stable housing, leading to homelessness (Nilsson et al. 2019).

Stereotypes and preconceived notions that conflate homelessness with mental illness and substance use disorders are harmful. It is important to understand the variety and complexity of issues affecting individuals in the community and on the transit system. Transit systems are looking to address many of these issues under one umbrella, but it is important to not conflate the responses.

Historically, public perception about the causes of homelessness has not always agreed with what the data show. Housed community members may believe that people became homeless because of a substance use disorder or serious mental illness. However, perceptions have been changing. A public opinion study in 2016 found that, compared to 1990, respondents “endorsed more compassion, government support, and liberal attitudes about homelessness” (Tsai et al. 2017). Personal experience of hardship during the economic recessions of 2001 and 2007 through 2009 may have made it easier for the public to view homelessness as driven by issues related to the economy instead of individual behaviors such as a perceived unwillingness to work (Tsai et al. 2017). Similarly, Phillips (2014) found that the public attributed homelessness to poverty

and job availability, and then to substance use disorders and mental illness. Both studies still found that housed community members continued to view personal behaviors and disabilities as factors that contribute to homelessness. As transit agencies create or expand programs to respond to homelessness, understanding public perception about the causes of homelessness may help the transit agencies better respond to housed transit riders’ concerns.

2.5 Criminalization of Homelessness

Homelessness is stigmatized in the United States and often addressed with criminalization and hostile policies that may violate, rather than protect, the rights of the people involved. Negative stereotypes and misinformed preconceived notions can increase discrimination, violence, and hate crimes against people experiencing homelessness. Research has shown an association between the criminalization of homelessness (such as panhandling, vagrancy, and anti-camping laws) and distrust of police, unwillingness to seek help, and emotional response of feeling victimized (National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty 2015; Bailey et al. 2020). When people objectify or dehumanize individuals experiencing homelessness, it can make it easier to treat people poorly. Understanding and working to eliminate biases associated with homelessness help to humanize those individuals and promote effective change through empathy.

A rise in encampments and people living in public spaces and in the transit system has resulted in harmful public narratives and hostile policies. Cities and transit agencies may have legislation (e.g., ordinances on camping and loitering) and policies (e.g., banning certain items or rules related to the use of the system) in place to guide behavior on the system (Ding et al. 2021). These policies and regulations can be effective and, in some cases, necessary for safety, but they also force punitive responses to homelessness, which can put law enforcement officers in difficult situations and promote the criminalization of homelessness. The increased interactions with the criminal justice system and associated trauma can set people back on their path to housing and disrupt the work of ending homelessness.

Law enforcement officers are often put in positions to conduct sweeps, confiscate property, and cite, arrest, or commit individuals (Rankin 2021). These policies tend to look to remove individuals from locations, although these practices tend to only disperse or displace individuals temporarily. Homelessness advocates and researchers have called into question the effectiveness of these practices (Bailey et al. 2020; McNamara et al. 2013).

2.6 Federal Government Response to Homelessness

For many jurisdictions in the United States, the federal government is the main source of funding for affordable housing and homelessness services. In 2019, it provided $78 billion for housing and community development programs, $38 billion of which was transferred to state and local governments, equivalent to “two-thirds of state and local spending on these programs” (Urban Institute n.d.). HUD is the main federal department that implements homelessness policy and programmatic activities and disperses funding (U.S. Government Accountability Office n.d.).

While HUD drives homelessness response and funding, the federal government recognizes that the complexity of homelessness requires interagency support and coordination. The U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness (USICH) provides a collaborative space for the multiple agencies that provide responses to homelessness. USICH is a 19-member interagency and interdepartmental group. This group “coordinates the implementation of a federal strategic plan, strengthens the capacity of state agencies and community-based organizations, and provides

expert guidance and support to member agencies’ homelessness-related activities” (U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness 2021). USICH also provides guidance to local communities responding to homelessness.

Other agencies that address homelessness include the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and the U.S. Department of Transportation (U.S. DOT). The VA provides programmatic guidance and funding for housing and homelessness services for veterans. The U.S. DOT announced in 2022 that the FTA would invest $13 million in grants to address homelessness through affordable housing and transit planning (U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness 2022a). In support of the Biden Administration’s “House America” initiative, the federal–local partnership launched by HUD and USICH to address the homelessness crisis, the FTA is looking to prioritize transit-oriented development (TOD) planning grants in areas of high incidence rates of homelessness to integrate land use and public transportation planning with a new fixed-guideway or core-capacity transit capital investment.

In 2009, HUD created the CoC program to administer federal homeless services funding and programs at the local level. Begun in 2009 through federal legislation, this program:

is designed to promote community-wide commitment to the goal of ending homelessness; provide funding for efforts by nonprofit providers and state and local governments to quickly rehouse homeless individuals and families while minimizing the trauma and dislocation caused to homeless individuals, families, and communities by homelessness; promote access to and effect utilization of mainstream programs by homeless individuals and families; and optimize self-sufficiency among individuals and families experiencing homelessness. (HUD Exchange n.d.f.)

This legislation is implemented by CoCs across the country at a geographic scale akin to a county or city. Each CoC has its own jurisdictional boundary and staff members. The CoC works with homeless service providers to promote more efficient service delivery, identify service gaps, and create new programming and policies. A CoC administers HUD’s federal funding allocations to local communities and maintains its local homelessness management implementation system database. A CoC board oversees the work of the CoC staff and is composed of community stakeholders. CoCs are a likely place for transit agencies to identify partners and leverage their responses to homelessness.

To reach the Biden–Harris Administration’s Federal Strategic Plan goal to reduce homelessness by 25% by January 2025, HUD and USICH launched in 2021 House America: An All-Hands-on-Deck Effort to Address the Nation’s Homelessness Crisis to invite mayors, city and county leaders, tribal nation leaders, and governors into a national partnership to rehouse people and expand affordable housing under the Housing First approach. All In: The Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness is a multi-year, interagency blueprint to end homelessness and to provide everyone in the United States a safe, stable, accessible, and affordable home (U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness 2022b). The All In plan serves as a roadmap for federal action and coordination between agencies to ensure that state and local communities have sufficient resources and guidance to build the effective, lasting systems required to end homelessness.