Population Health Funding and Accountability to Community: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 2 Context and Overview

2

Context and Overview

Meshie Knight, a program officer at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF), moderated the first panel, consisting of Karen Minyard, chief executive officer of Georgia Health Policy Center, and Kristin Giantris, the interim chief client services officer at the Nonprofit Finance Fund. Knight offered a brief overview of the work of RWJF on population health funding and accountability to community and the unprecedented moment to “harness the opportunitiaes” available at the local, state, and national level. In the wake of COVID-19, many people

are reimagining what it will take to “realize a more just and equitable society,” she said, and what must be done differently. She emphasized RWJF’s commitment to accountability to people, especially people with a history of marginalization. When speaking of accountability to community, Knight said, the question may arise “accountability to community for which sets of things?” The short answer, she said, is “well, everything.”

Knight called attention to the 2014 workshop on population health financing, where David Kindig—one of the roundtable’s founding co-chairs and an emeritus professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison—invited participants to think about how much money is needed and where to invest funds to generate the biggest impacts in improving health, along with reducing the health inequities that exist in the United States.1 Knight identified an important lesson learned during the interim: “only when communities are centered in the change that we see, their voices are heard, their ideas and solutions are sought, and they have influence over the decisions that affect their lives, will we realize a different, more equitable future.” Knight said that although population health has traditionally been driven by a transactional approach that prioritizes technical proficiency, the field needs to shift toward building community trust, power, and relationships that are “tantamount to success on any endeavor that seeks to reimagine” existing paradigms.

Knight outlined evidence of significant progress since 2014. Despite “a legacy system that was not designed for the type of collaboration and alignment that is necessary to realizing health,” she offered examples that show the power of working across sectors with greater transparency and shared accountability in financing to improving the public’s health, including:

- The role of regional collaboratives in encouraging, developing, and testing the implementation of new funding and financing models of population health, including ways in which health care and non-health care sectors integrate social services, experiment with governance structures, and effectively manage partnerships for population health interventions.

- Efforts that are closely examining the relationships between health care institutions and community-based organizations, power dynamics, and the importance of centering communities.

- The development of local wellness funds, a promising approach to sustainably assemble resources to finance community prevention efforts.

___________________

1 See the workshop page at https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/02-26-2014/resources-for-population-health-improvement-a-workshop (accessed October 3, 2022).

- Insights on new ways to think about hospital community benefits, including hospital charitable resources, how they are allocated, and how they benefit community wellness and prevention.

The field is at a crossroads, Knight asserted, as financial resources designated for structural improvements flow into communities and, based on lessons learned since the roundtable’s exploration of the topic in 2014, partners know more about what is needed to lead a successful intervention. The lessons learned inform the work aligning dependable, long-term revenue streams to fund effective population health efforts. An important insight, Knight said, is that the greatest opportunities for systems change are found in communities.

To begin the panel presentations, Knight introduced Karen Minyard, the chief executive officer of the Georgia Health Policy Center. Minyard described her professional path to understanding how money flows into communities and how her interest in this topic led her to pursue a Ph.D. Minyard studied how decisions regarding money are made and who decides where money goes in a community. Over the last 8 years, her work has focused on innovation and financing across sites in the United States, and, to illustrate, Minyard offered two examples of how communities on the ground are shaping broader population health impacts by showing a map with sites of community-based financing work that she has studied.

First, the Local Initiative Support Corporation Toledo, a community development financial institution, has a local focus that goes beyond giving grants and loans to building relationships with local partners. The institution invests in low-income housing and actively advocates for contracting opportunities for local and Black and Indigenous people and people of color. Minyard highlighted Toledo’s Twilight Market which showcases small businesses owned by Black and Indigenous people, other people of color, and immigrants. Then she described how in Yamhill, Oregon, a Medicaid-managed care company reinvests its health care savings (i.e., from quality incentives) into its local wellness fund, including requiring contractor contributions to the fund, having a community board that guides how the funds are used, and focusing on investing these funds upstream.

Minyard spoke about her center’s local wellness funds website,2 which provides opportunities and information to help people navigate the process of organizing local funds. Local wellness funds are intended to address crosscutting factors such as community voice, equity, racial

___________________

2 A local wellness fund is a “locally controlled pool of funds created to support community well-being and clinical prevention efforts that improve population health outcomes and reduce health inequities. For more information, see What is a Local Wellness Fund? https://localwellnessfunds.org/ (accessed September 14, 2022).

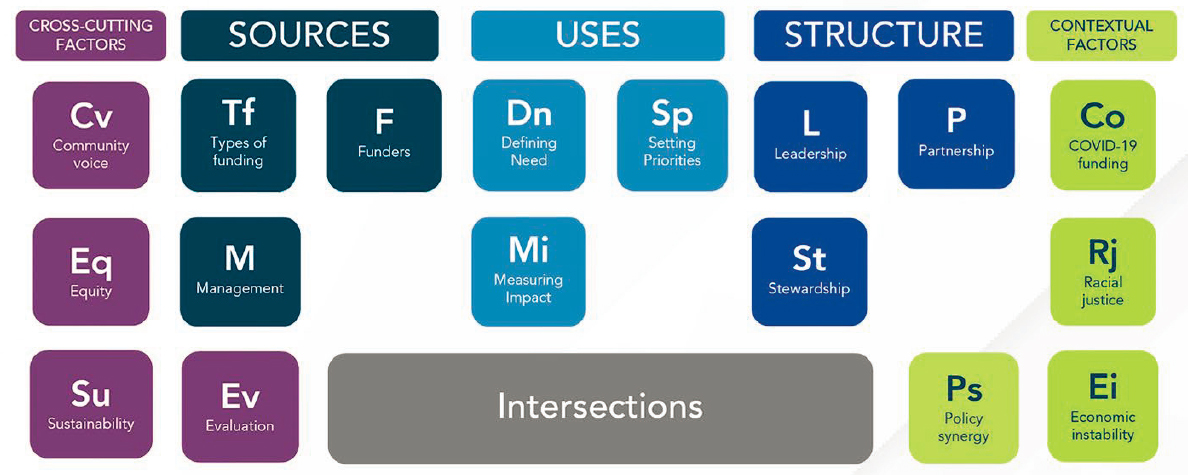

justice, and economic stability (see Figure 2-1). The website discusses the crosscutting factors, Minyard said, such as examining how a group overseeing a wellness fund can “get beyond having just one person at the table,” to creating an opportunity for community members to be involved in the decision making of where resources get directed.

The framework for the local wellness fund work, Minyard continued, is based on four key principles: purpose, data, governance, and financing. She said that the work led to a realization that community, community voice, equity, power dynamics, and trust are very important in meeting the goals and needs of the community. The local wellness fund website includes interactive resources for people to explore funding and tools to move toward meeting community goals and needs. The website also includes resources that address issues such as power sharing.

Minyard discussed the unprecedented funding opportunity in the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), comparing it and the infrastructure plan to the state attorneys general tobacco settlement (1998), the New Deal in the 1930s, and efforts to respond to the Great Recession. ARPA funding represents three times the amount of money spent on the Great Recession, she added. “Never in our history have we had this kind of money flowing to every town, every city, every county, every state,” she said. The funding opportunity allowed people in communities to work with their local governmental leaders and invest in community-driven priorities. ARPA funding, she added, provided an unusual opportunity for locally led efforts by removing the hurdle of communities having to go through the state or federal government to access the funding. The Department of Treasury allocated $350 billion to local governments, an amount augmented by funding from various federal government departments and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. The funding, Minyard noted, can be woven together with local, state, and federal money to support communities and address the social and economic disparities so clearly demonstrated during the pandemic. Minyard outlined four key principles that she and her colleagues at the Georgia Health Policy Center (GHPC) identified to get people connected to the money:

- Aligning the money for equity.

- Thinking about the short term and the long term. Some resources are available until 2026.

- Using intermediary organizations to help the money flow in easier and faster.

- Allowing communities to drive the change.

Minyard discussed an existing pilot program, using asynchronous modules, which trains people as funding navigators. The goal of that

SOURCE: Minyard presentation, June 22, 2022.

program is to create a “legion of funding navigation” where every community has support. Funding navigators would use the GHPC-developed FramingFunds.org website,3 which identifies all available ARPA funds by city, county, or state. Alternatively, a search by special interest and social determinant of health is also possible. Funding navigators would use the tool to help communities define how these unprecedented resources are used to improve well-being.

Kristin Giantris, the interim chief client services officer at the Nonprofit Finance Fund4 (NFF), was the next panelist to provide a presentation. Giantris first described the long history of the Nonprofit Finance Fund working with community-based and social sector organizations “rooted in community” and then introduced the Advancing Resilience and Community Health (ARCH) project, which operated between 2018 and 2021, as an example of a community-based organization (CBO) partnering with health care partners outside of existing ecosystems. ARCH began, Giantris said, with the hypothesis that networks of CBOs would be better equipped than CBOs working individually to meet the complex needs of clients and to contract with health payers looking to address the social determinants of health. Giantris identified three key benefits of the network approach: (1) scalable solutions to better address social determinants of health for everyone, (2) easier access to services for health care, and (3) a community-based voice to address power imbalances between CBOs and health care. The project was premised on a network of CBOs expanding their range of services, consolidating data sharing, negotiating power, and measuring success based on paid CBO contracts with health payers.

Three networks were part of ARCH—Twin Cities, New York, and Charlottesville—and together they addressed substance abuse, homelessness, housing, and multiple social services in frontline communities. The organizations involved in ARCH were “deeply connected to their community,” Giantris said, but they were also led by white men. ARCH partners were required to have strong relationships with health care partners, she said, particularly “partners who were well resourced, well established, and well connected” in making progress toward securing contracts with health payers, which was used as the measure of success. Had the project been conducted more recently, Giantris said, there would have been greater attention paid to centering organizations that did not have access.

Giantris highlighted three key takeaways from the project, based on feedback from the partner CBOs. First, growing financially viable partnerships between CBOs and health care organizations was not easy, even

___________________

3 For more information, see https://fundingnavigatorguide.org/dashboard/ (accessed August 28, 2023).

4 Nonprofit Finance Fund: https://nff.org/ (accessed August 28, 2023).

with networks. Partners operate with very different business models. While health care organizations are focused on treating individuals for health-related needs and reducing the cost of care, CBOs are looking to influence community outcomes on a different timeline and a different measure of cost. Second, frontline networks provided the critical glue to effectively bring a community together. The ARCH effort was not tapped into all the networks at the frontline of community needs (e.g., organizations led by people of color), and, as a result, it did not act to even the playing field for communities of color. Third, the outcome may not hold everywhere, but the investments ARCH pursued were not profitable, even for well-resourced organizations. The more removed organizations were from the health care establishment, the harder it was for them to demonstrate financial viability.

NFF partnered with Mathematica for qualitative research with ARCH participants and offered two additional observations (Jean-Baptiste, 2021), Giantris said. First, health institutions were focused on how to perform work that is focused on addressing the social determinants of health. In helping families address health-related social needs at the individual level, health institutions assess those families’ access to healthy food, consistent transportation, and affordable housing, which can all be measured in terms of return on investment. However, the view of the social determinants of health is broader for community-based organizations that operate further upstream, which prioritize equity-related issues and relationship building. Giantris’s second observation was it is important to find ways to invest in the “broader issues of structural need and structural change.” While health care institutions tend to focus on the “short-term vision” of the social determinants of health, CBOs focus on building relationships that require “a larger investment of time and resources to build trust.” There has been a move away from transactional and toward more relational approaches to addressing systemic inequities, she said.

In closing, Giantris said that there are no shortcuts to creating efficiencies, cost reductions, and ways to scale partnerships through networks. Large, long-term investments are needed to go beyond the partnership to address historic inequities. Giantris also identified the critical role of federal dollars and investments in “changing the structural inequities and allowing the incentives to be in place to invest in the system change.” This is a key component for these partners to come together, build trust, and develop equitable relationships, she said.

AUDIENCE DISCUSSION

To begin the discussion section of the panel, Knight asked the panelists to share what they have learned are potential catalysts for trust and

alignment to aim towards what’s possible. Minyard responded that trust takes time to establish. She also noted that tools that help people look at the continuum of power can be useful in identifying who holds power and how it can be shifted. People can make small shifts (e.g., being quiet a little bit longer to allow someone else to speak) that are valuable and important. Knight followed up with a question to Giantris about her remarks on redefining measures of success. The question was about how to work differently with measurement systems to reflect more equity and community engagement within efforts to improve population health. Giantris reinforced Minyard’s comments about “relationships moving at the speed of trust” and that building community trust takes place on many levels, whether through deeply embedded individuals or community organizations that understand the needs and how to respond. Authentic engagement, Giantris continued, means adopting community as “leading voices” that define the change. Engagement cannot be limited to “input,” needs assessments, or check-ins at the beginning and end of the process. Instead, she said, “those [community] voices have to be at the table the whole time,” including defining how the money will flow. In practice, this involves “time upfront with community leaders” and their continued investment throughout the process. Giantris told an anecdote about working in an organization that had been white led for 40 years and the realization that the assumptions based on technical knowledge are almost always wrong. Those seeking to bring about transformative change, she said, need to “listen and follow the lead of the people in the community.”

Knight asked Minyard to explain the urgency of the ARPA resources in the community and the timeframe for putting best practices into use with those funds. Minyard emphasized the fact that money is available in every town, city, and county and that it “has to be encumbered by the end of December 2024 and spent by 2026.” There is time for relationship building, including relationships between community collaboratives and their local governments. Minyard provided an example of a group with an existing relationship to a county commission. Instead of asking for more money for this year, Minyard recommended negotiating for an increase in the budget through 2026.

She also shared a story on building relationships:

One person told me that she went to every county commission meeting for years, and she wanted to have a relationship. She hoped that at some point they would give her money. This was before the pandemic. When they asked for someone to say the prayer at the county commission meeting, she volunteered. Every month she said the prayer. She got to know the county commissioner, and they got to know her. Then when the COVID money came, she was able to say to them, “You know me, I know you. Could we use some of this money for my project?”

These types of local relationships and communications for local money can happen now, Minyard said. There is also other ARPA money that can be combined. The Local Wellness Fund, Knight added, is one example of the different types of roles and governing structures that can exist “to accelerate the pace of some of these partnerships.”

Knight directed the next question to Giantris, which was to talk about the important factors that facilitate a real and living collaboration that includes trust and power sharing. Giantris reiterated the importance of established relationships as a lesson from the ARCH initiative. Giantris told the story of the Metropolitan Alliance of Connected Communities (MACC) in Minnesota, a 40-year-old organization that includes a variety of different types of CBOs, including human services and frontline organizations. This is an example of a trusted relationship where the Nonprofit Finance Fund provided support, she said, given MACC’s ability to “explore different types of partnerships with health payers” at the network level. MACC helped its members’ organizations understand how to adjust services, business models, and relationships “to facilitate those partnerships” and benefit from the changes. In the process, the ARCH team had to be very sensitive to the needs of partners. Giantris observed that network leaders benefitted from the opportunity to talk to each other. These one-to-one relationships did not require the interference of an outside facilitator and were conducive to peer learning.

The last question that Knight asked the panelists was whether they had any examples of a situation where harm was done and rectified and if relationships were strengthened as a result. Minyard provided an example of a short documentary about community relationships and community involvement. (The documentary is generally shown as part of a 90-minute interactive experience.) The story documented a longtime community collaborative with a university. A problem arose when the university received funding for a project built on the lessons learned from the community collaborative, but in their rush they did not inform the people in the community, leading to broken trust. The documentary transformed into an opportunity to lead a “mediated process of rebuilding the trust” and “to mend that history,” she said. Minyard explained that the broader issue is that people from various organizations go into communities to learn and conduct their work, often with good intentions, but they depart in ways that are “not generative to the community,” thus breaking trust and making the community less interested in partnering and supporting such work in the future. Rather than “coming in with anything” to the community, Giantris added, the role [of people representing institutions] should be to listen, learn, and respond “based on what has been asked of us from that community.” To build trust, she continued, the process needs to move from tight artificial timelines and measurement

that are not relevant to community and toward shifting power. Local, city, or county-level agencies regularly and repeatedly make the mistake, Giantris said, of pushing “innovative programs” in the community while moving too fast and without enough information “for a community to be actually engaged.”

Knight emphasized that “fundamental change in both accountability and financing improvements in population health is foremost about relationships.” Population health improvement work is also about reparative justice. Knight concluded by referring to a comment from the chat that “building trust is moving from a place of building trust to demonstrating trustworthiness.”