Population Health Funding and Accountability to Community: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 5 Research and Evaluation

5

Research and Evaluation

Richard Vezina, a senior program officer at the Blue Shield of California Foundation, moderated the fourth and final panel of the workshop. The panelists included Seth A. Berkowitz, an associate professor of medicine at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Melissa Jones, the executive director of the Bay Area Regional Health Inequities Initiative (BARHII); and

Barbie Robinson, the executive director of Harris County Public Health in Texas. This panel discussion focused on the role of research and evaluation in population health funding and accountability to community.

Vezina opened with a brief overview of how research and evaluation serve many purposes in the health care and public health prevention fields but have a long history of sometimes being used in ways that were extractive or harmful to the communities it was trying to benefit. The panel drew on examples from a wide range of approaches to using research and evaluation to promote population health and ensure accountability to the communities most affected by health inequities.

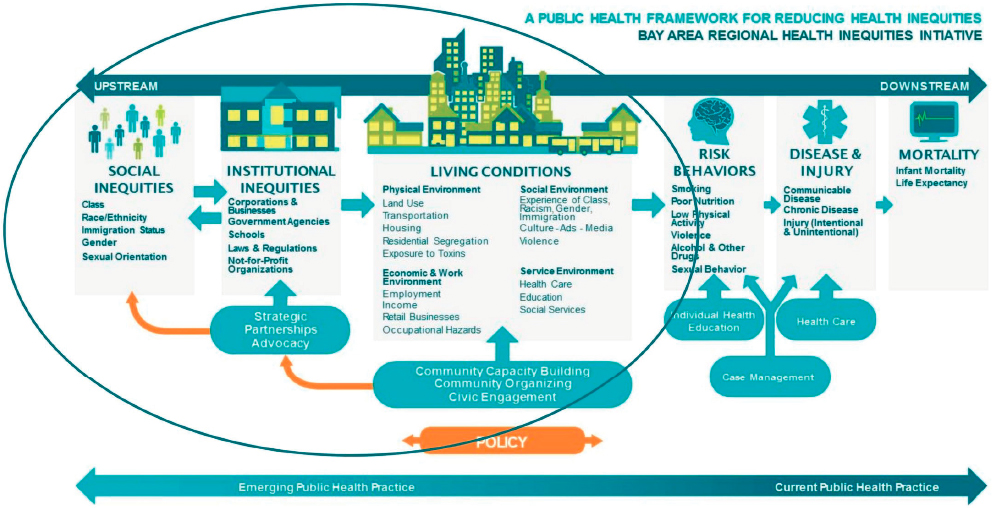

Vezina first introduced Melissa Jones, who began by explaining that BARHII is a coalition of Bay Area public health departments working in collaboration with the community. BARHII has a committee of senior leadership across the nine-county Bay Area, Jones said, which is focused on health equity and a very specific charge—“identifying and implementing regional initiatives related to the social determinants of health.” Jones listed a few examples of strong outcomes: prioritizing issues for regional training, establishing regional professional standards for equity issues, developing a protected space for peer learning, creating positive peer pressure for equity transformations inside departments, and creating relationships across departments to help equity advance across the region. She shared an image of the BARHII framework (see Figure 5-1), which is built on the understanding that much of what matters for health happens outside the doctor’s office. In other words, Jones said, community conditions, institutional factors, racism, sexism, and undue pressures affect individual health over time.

The BARHII framework is similar to one embraced by the World Health Organization, and it appears in many public health textbooks and was used by the California Department of Public Health to design the Office of Health Equity in California. The framework was used to advance three important BARHII initiatives during COVID-19, Jones said, which had clear life-saving outcomes for communities in the Bay Area. Often, conversations about evaluation center on individual health outcomes, Jones observed, but there is more that can be done at the intersection of health outcomes and community conditions.

First, BARHII put together research on the impact of evictions and housing stability on health. While this work had been done by BARHII over many years, there was a renewed need for it during COVID-19, Jones said. The work was shared with community groups across the region that were watching declines in income during COVID-19, becoming increasingly concerned with the high cost of living in the Bay Area, and concerned about residents being unable to pay rent, potential evictions, and the threat of homelessness. BARHII also shared the research

NOTE: BARHII = Bay Area Regional Health Inequities Initiative

SOURCE: Jones presentation, June 22, 2022; BARHII. https://barhii.org/framework (accessed August 22, 2023).

with communities in the Bay Area that did not have a previous history of county-wide tenant protections and supported these communities with additional research (e.g., sharing data sheets with food banks, housing counseling agencies, and others) to ensure they had real-time data to understand the need for an eviction moratorium. As a result, the Bay Area had full coverage in COVID-19 eviction moratoriums, which created momentum for the statewide eviction moratorium and the federal eviction moratorium that followed. This was an incredibly important outcome, Jones said, adding that research from universities in Southern California has shown that lives were likely saved as a result of the eviction moratoriums that kept people out of homelessness during COVID-19.

Second, as shutdowns were happening in the Bay Area and across the country, there was a lot of uncertainty about the risk of COVID-19 when being outside in parks. BARHII worked with the deputy health officer and the Bay Area park directors to develop indicators and design strategies that kept the transmission risk low, keeping the parks open. As a result, parks in the Bay Area reopened and remained open so that families had a place for recreation, health, and reduced stress during the pandemic. This work is very important, Jones said, and shows the value of collaboration among community partners, universities, deputy health officers, and park directors across the region.

Finally, early in the pandemic there was no individual person assigned specifically to address issues surrounding equity, Jones said, and so BARHII, in partnership with collaborators across the country, collected data on how equity was being integrated in COVID-19 responses. BARHII shared the findings in a report, webinars, and trainings across California, including work with the Public Health Alliance of Southern California. BARHII also hosted a local monthly community of practice for equity officers in the Bay Area, which resulted in getting equity officers assigned across nearly every county in the region. BARHII supported these equity officers in identifying places where a disproportionate number of deaths and losses occurred, while collaborating with skilled nursing facilities on improvements. The work extended to community task forces and partnerships, including farm workers and other groups highly affected by COVID-19, to ensure adequate responses to their needs and allocation of recovery resources.

Jones pointed to “this type of momentum” as emblematic of BARHII’s commitment to evidence-based outcomes at the intersection of health disparities. Momentum across the region and the public health field can save lives. In the last 20 years, she said, the field of public health has progressed and changed, but BARHII still firmly believes that research, data, and stories must play a critical role in understanding the design of the next phases of the work. Jones pointed out that “there are limits to what government can do without community, what health care can do without

public health” and that strong community partnerships and evaluation are undeniably important components of the work. At BARHII, conversations about the recovery from COVID-19 and the scale of economic recovery are now focused on what is needed after 3 years of global change. Jones said that the vision for recovery is to create a more equitable situation than in 2008, when there were dramatic differences in housing, tenure of home ownership, and rent burden rates for people who never fully recovered. There are also now federal resources to change these patterns and an opportunity to use the experience of managing an ongoing crisis and treating health equity as an emergency.

Jones concluded by proposing actions that organizations and people engaged in this work should consider:

- Developing a national, racial health justice action lab1 focused on quick learning, fast sharing of what works, and immediate implementation, similar to what BARHII did for COVID-19 in prioritizing eviction moratoriums and other strategies;

- Producing resources for community coalitions on the ground that build on the Ryan White Care Act, which provided a level of baseline infrastructure for HIV/AIDS work;

- Continuing to implement race-specific strategies, following in the steps of over 220 jurisdictions that have passed “racism as a public health crisis” proclamations; and

- Developing regional infrastructure models for collaboration.

Vezina then introduced Barbie Robinson, the executive director of Harris County Public Health in Texas. Robinson discussed a major initiative called the ACCESS (Accessing Coordinated Care and Empowering Self Sufficiency) Harris County Initiative. ACCESS provides a framework for a “coordinated, client-centered, service delivery model” for improving the “well-being, self-sufficiency, and economic independence of the county’s most vulnerable individuals,” Robinson said.

The model was created in the Bay Area of California, while Robinson was director of health services for Sonoma County. ACCESS is a model for delivering services to vulnerable populations within the community, specifically focusing on the challenges that local governments face with siloed programming, access to information and data, and funding, all of which affect the ability to provide care for vulnerable populations. The model brings together county frontline staff across the safety net (e.g., health, human, law enforcement, and criminal justice partners) to integrate

___________________

1 For more information, see https://housingimpactbayarea.org/documents/2021/06/action-menu-for-racial-equity-action-lab.pdf/ (accessed August 24, 2023).

service delivery goals and strategies for vulnerable populations in need of services. The model is governed by the Safety Net Collaborative, which includes the executive leadership of all county and community-based organization departments. The value proposition is knowing that meaningful outcomes can be achieved collaboratively, Robinson said, whether that is getting people housed or getting people into mental health services or compliant with a medication regimen.

Robinson said that “collaboration without integration is really just another form of fragmentation.” The ACCESS model brings together partners to integrate services and systems to achieve more effective outcomes compared to when each works individually. She said that ACCESS allows partners to be accountable to communities by delivering individualized services, “an intensive wrap-around service delivery structure,” and that the model uses enabling technology from all safety net departments and community-based organizations to create a “holistic, 360-degree perspective of each of the clients that are participating.” Robinson explained that through this model, partners can understand individuals based on their specific needs, the different systems they use or intersect with, and how to support them. As individuals become more self-sufficient or stabilized in their needs, the services back away to allow individuals to move forward.

While in Sonoma County, Robinson used the integrated data hub to identify the most vulnerable populations and partners and used the data to advocate for policy and appropriations at different levels of government. This approach created an opportunity to prioritize the model of care, interventions, and services that were most important in meeting the needs of individuals.2

There is a lot of discussion around “engaging community and being accountable to community,” Robinson said. However, community engagement often gets stalled in “listening to the community,” when the reality is that partners need to continuously have conversations with the community and understand their needs. Conversations need to move beyond “I need X more widgets of inpatient beds or housing choice vouchers,” she said, toward how to bring these services to the most vulnerable and enable individuals to access and use these services across the safety net.

This type of model approach allowed for identifying and addressing inequities, especially those magnified by COVID. Robinson said the ACCESS model reflects one of her favorite African proverbs, which is that “when spider webs unite, they can tie up a lion.” Similar to a spider web,

___________________

2 Robinson said that in Sonoma County, experience with the ACCESS model demonstrated that African Americans were only 1 percent of the population yet were three times more likely to be in the safety net system or intersect with the systems of criminal justice, homelessness, economic assistance, or food assistance.

individual government organizations have limited resources and services, but when many join, they gain the strength to have a great impact. By bringing together different frontline staff, blending and pooling resources, the ACCESS model creates the enabling technology to fund this type of work. In other words, Robinson said, partners “tie up the lions of inequity as it relates to housing instability, economic insecurity, lack of access to health care, etc.” The model has the potential to achieve optimal outcomes and be replicated across the country. Partners have responsibility for the outcomes and service delivery to populations, and it is critical for them to be accountable to the community.

Vezina next introduced the final speaker on this panel, Seth A. Berkowitz, a primary care doctor and associate professor at the University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill. Berkowitz provided an overview of a study called Healthy Food First, a randomized clinical trial that is ongoing and, at the time of this workshop, still in the process of enrolling participants. The study is funded by North Carolina Blue Cross Blue Shield, and within UNC the co-investigators, along with Berkowitz, are Alice Ammerman in the Department of Nutrition and Darren DeWalt in General Medicine.

Healthy Food First is an intervention designed for people with food insecurity and high blood pressure.3 Its goals are to improve blood pressure as well as to inform policy design and address issues based on data-driven results. Berkowitz said that the study has three dimensions: testing a food subsidy versus a delivered food box to address food insecurity, a lifestyle intervention carried out with or without a community health worker, and duration, with the intervention lasting either 6 or 12 months. The goal is to maximize impact across the dimensions.

Berkowitz identified three important equity strategies that emerged from the research. The first was the use of a multi-sector collaboration with a health insurer, organizations that deliver health care, and community organizations. In this study, the food subsidy was delivered by Reinvestment Partners, which is a local nonprofit organization that focuses on issues of food and housing justice; the delivery of food boxes relied on a network of local food hubs that connect local agriculture to a distribution center. The second equity strategy was to adapt the lifestyle intervention, which is delivered by community health workers, to the local context. In this study, the curriculum adapted the principles of a Mediterranean diet to the North Carolina context (e.g., the Med-South diet), with the support from community partners over an extended period. The third equity strategy was to adopt evaluation strategies that appropriately addressed

___________________

3 What is Healthy Food First? https://www.unchealthcare.org/health-alliance/healthy-food-firstresearch-study/ (accessed October 3, 2022).

health-related needs or other social determinants of health. Berkowitz said that while a rigorous evaluation strategy is important, randomized clinical trials are not the only appropriate evaluation design. A research study should be designed so that everybody benefits or receives something for participating.

Berkowitz said that researchers need to be accountable to issues uncovered in the context of a study and consider the implications for recruitment and generalizability, given the subset of people who might be willing to sign up for a study. He also emphasized that minimizing participant burden can both help ensure scientific validity and respect participants’ time. In this study, food boxes were delivered to people’s homes, food subsidies were issued through an electronic card, and the lifestyle intervention was delivered over the phone or video at the patient’s preference. Additionally, primary data collection was done over the phone, and such information as blood pressure was collected from electronic health records during routine care. Berkowitz reiterated the need to “minimize participant burden” and posed the question, “If you are going and getting your blood pressure measured by the doctor’s office, do we really need to make you come in for a study visit just to do it?”

Berkowitz said that the Healthy Food First study demonstrated the ability to capture multiple effects beyond a single primary outcome. Evaluation strategies should aim to capture as many outcomes as possible, he said; otherwise, the intervention is underestimating the accomplishments. For instance, capturing blood pressure, a clinical outcome, can be complemented with health-related social needs (e.g., food insecurity improvements) and participant-reported outcomes, such as health-related quality of life, which are not easily captured in electronic health record or claims data. While this approach requires dedicated data collection, it also leads to a better understanding of how addressing food insecurity and improving diet affects health-related quality of life. Additionally, it provides insights into health care use and costs, which affect the design of health insurance benefits and the sustainability of interventions. Ultimately, Berkowitz said, this work demonstrated the importance of multisector collaboration, community involvement, rigorous study design, and evaluation of a broad range of outcomes.

AUDIENCE DISCUSSION

Vezina opened the discussion with questions for Robinson regarding how ACCESS is funded. Specifically, Vezina asked about the relationship between funding and results and how the model integrates different teams to meet the diverse needs of the communities served. To address the second question, Robinson pointed to the value proposition

of ACCESS and the expectation that all safety net departments within the county and community deliver results, whether it pertains to housing, access to a medical provider, or enrolling in medical care. The value proposition does not only require delivering the expected outcomes or services that get individuals into the safety net, she said, but also getting them out of the safety net and improving well-being and self-sufficiency. Robinson noted that one challenge of the work was providing effective mental health services to individuals who are homeless. People in need of both housing and mental health services first need to be stable enough to use the housing effectively.

Robinson also discussed how, within the criminal justice system, local jails say they are “running the largest mental health facilities in the country” because people with mental health or other economic challenges (e.g., poverty, trauma) are intersecting with that system. The reality, she said, is that these people should be served by other places on the safety net continuum. Robinson reiterated that “the value proposition for the executive leadership across those systems, as well as the expectations of elected leadership is what led to everyone leaning in and coming to the table and collaborating.” Every executive, including the public hospital system director, sheriff, probation chief, and executives within public health and housing is at the table because they understand the value proposition and the expectation to deliver results.

Elected leaders passed resolutions in both Sonoma County and Harris County, Robinson continued, telling government “You will not divide the body up and silo it and compartmentalize how you deliver those services.” In most cases, frontline staff are already committed to delivering effective outcomes and value the ACCESS model. In response to the question related to funding, Robinson said that ACCESS pools together resources from health, human probation, and hospital partners to fund the technology that drives the development of care plans, uses and aggregates the data from a policy perspective, and prioritizes funding requests. Partners collectively “peel back the layers” to determine which initiatives need funding.

Vezina observed that much of this work involves building political will and asked all three panelists if they could speak to the use of data, evaluation, and research in building political will and influencing policy. Jones began by discussing how, for a coalition of public agencies hoping to affect health equity more quickly, data and audience are important to understanding which policies are having the most impact on community health. It is also important to share results with the community and other jurisdictions and to understand how historic patterns and policies shape existing ones. Jones offered the example of BARHII working on eviction moratoriums in the Bay Area even prior to COVID, given an already

high-cost housing market. In this case, BARHII already knew how to help prevent people from sliding into homelessness. Policy analysis helped BARHII assess a range of outcomes that matter for health, including family stress, economic and mental stress, and the likelihood of becoming homeless. BARHII used the data with administrators, elected officials, and community partners to better understand what policies would and would not work.

Berkowitz underscored the importance of knowing your audience and pointed to the role of narrative stories in driving momentum on policy priorities. However, even with compelling stories, Berkowitz said, it is still important for narratives to be aligned with data and evidence. The work of research and evaluation often benefits from having a human face to illustrate the issue or impact. “It is critical that data is alive and used in an operational and administrative way,” he said. The next step, Robinson continued, is taking the aggregate and the data hub and identifying those who are most vulnerable. For example, the policy lab at University of California, Berkeley, was able to define vulnerability based on the systems that people interact with, the types of services used, and the cost of those services. This provided a snapshot of vulnerable populations in Sonoma County and highlighted their specific needs.

Next, Vezina asked the panelists to speak about how to ensure that data and the results of evaluation work get back to community members and community organizations. Robinson said that because the work is directly tied to affecting those experiencing the safety net system, it is critical to share data and outcomes that drive equity. As a former member of BARHII, Robinson said she recognized the work Jones has done to help frame and drive access work in Sonoma County, including a powerful portfolio of interventions, services, and policy areas that supported communities, especially during COVID.

Jones added that the goal of BARHII is to publish brief reports that are publicly available. BARHII has found that limiting reports to three to five pages and incorporating accessible graphic design allows practitioners, elected officials, and community members to easily understand and review the key findings. As a former evaluator, Vezina agreed with the importance of providing “brief and highly accessible” information. He next asked the panelists how they navigate findings that are “not glowing” and how policy makers, funders, and partners can make sense of findings when they are not was what was hoped for.

As a government official at the local level, Robinson emphasized the importance of “managing and communicating about how difficult this work is,” particularly in the context of historical institutional racism and disparities coupled with complex, population-level challenges. This work requires time to achieve the outcomes funders want to see. There

is also urgency in this work to avoid continuing a “multi-generational cycle of disparities” and reframe discussions on how to best address the challenges that are faced. Berkowitz added that for any kind of empirical study, including research evaluation, the focus is on answering a technical question rather than on answering general moral questions on what should or should not be done. Research cannot answer whether it is good to help people who are experiencing homelessness or good to try to address health-related social needs. “That is a moral judgment that we all need to make,” he said. The research can help make sense of whether interventions are leading to the desired outcomes and whether people are benefiting from other safety net programs or federal income support.

In closing, Vezina asked the panelists to provide insights on opportunities for the audience to use their research, evaluation, and data in service of being accountable to communities. Jones recommended identifying “bright spots” of success across the nation and figuring out how to scale those interventions to other locations. Jones clarified that scaling does not necessarily mean one organization or program growing bigger but is about creating the innovation network across the country to get to health equity faster. Even if evaluation work has disappointing results, Jones sees this as an opportunity for adaptive leadership and to think differently and reframe an issue to get the transformations envisioned. Berkowitz offered a “comparative effectiveness frame” for answering technical questions, in which issues are identified and then the research or evaluation is used to help identify plausible approaches to get to the desired outcomes. Finally, Robinson pointed to the importance of research that lends itself to setting up policy discussions for both operational and administrative outcomes.

This page intentionally left blank.