Population Health Funding and Accountability to Community: Proceedings of a Workshop (2023)

Chapter: 3 Progress in Population Health and Health Equity Funding

Marsha Lillie-Blanton, an adjunct professor of health policy and management at the George Washington Milken School of Public Health, moderated the third panel, consisting of Kimberly DiGioia, a program officer at the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute; Suma Nair, the director of the Office of Quality Improvement at the Bureau of Primary Health Care in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Health Resources and Services Administration; and Lauren Taylor, an assistant professor in the Department of Population Health at the New York University Grossman School of Medicine.

Lillie-Blanton opened the discussion by saying that as a society, “we have been fed a steady diet of messaging that says what is needed to be healthier is more and better medical care.” And, she added, when her loved ones are sick or injured, she wants them to have access to the most advanced medical technology and skilled health professionals who are “capable of addressing their problems.” These statements, Lillie-Blanton said, illustrate why it is so challenging to in fund population health and rebalance a trillion-dollar health system to both ensure access to high-quality care and to support upstream factors (e.g., education, housing, neighborhoods) that are safe, effective, and equitable.

Although health is largely produced by investments outside of a traditional health system, Lillie-Blanton said, the public generally has limited understanding of the role of broader social determinants of population health. Instead, the public’s focus tends to be on what happens when people are ill or injured, and, in terms of funding, decision makers often focus on what the public values or understands as the forces driving their health outcomes. Still, despite this reality, the United States has made progress in “expanding resources” and changing mindsets in the realm of population health and health equity, Lillie-Blanton said. She offered three examples of progress:

- Although community benefit spending has historically focused on uncompensated care, as defined by hospitals, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) introduced new requirements for community health benefits, including a category called “community health improvement.” The change opened the door for state, local government, foundations, and community groups to partner with hospitals on population health investments.

- The Biden–Harris Administration has centered equity practices and outcomes across all sectors of government. The Department of Health and Human Services Equity Action Plan offers an example of how a federal agency operationalizes equity for underserved communities (HHS, 2022). Another example of how equity is centered by the administration is in the federal rule which defined

- equity as a central aspect in determining where the $350 billion funds of the American Rescue Plan Act get dispersed.

- Health systems, health insurers, and institutions in other sectors (e.g., the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Morgan Stanley, the Kresge Foundation, and the Local Initiatives Support Corporation) represent a new generation of funding, thought leadership, and investments aimed at creating greater equity in this country.

Lillie-Blanton then introduced Kimberly DiGioia, who provided an overview of findings from her previous dissertation research on the effects of Medicaid expansion on hospital community benefit expenditures (DiGioia, 2022). Nonprofit hospitals receive federal tax exemption in exchange for the charitable activities they offer, which are known as community benefits. DiGioia noted that about two-thirds of hospitals in the U.S. are nonprofits, spending between 8 and 9 percent of their total operating expenses on community benefits. DiGioia explained that the vast majority of community benefit spending goes toward the cost of care, charity care (called financial assistance), and unreimbursed Medicaid services while a small amount of this money goes to community health improvements, including education in the health professions, subsidized health services, research, and cash and in-kind contributions to community organizations.

The passage of the ACA, DiGioia said, generated a sense of optimism that hospitals would report more revenue and less uncompensated care as more patients gained access to coverage and affordable care. If the prediction held, this could also lead to “more spending” on community health improvements rather than just discounted care. The evidence has shown that more Americans are covered, she said, and “hospitals in expansion states reported increased Medicaid discharges and decreased uninsured discharges.” There was indeed a decline in uncompensated care, but this was offset by an increase in unreimbursed costs associated with caring for Medicaid patients. As a result, Digioia said, “community health improvement spending did not increase as expected.” A summary of her study, based on her slides and remarks, is provided in Box 3-1.

In closing, DiGioia added a few high-level observations from her research:

- Community hospitals supported a much higher increase in Medicaid shortfall compared with the reduction in financial assistance. The change in Medicaid shortfall was nonsignificant.

- Hospitals and counties at the highest rate of uninsurance reported a nearly 7 percent decrease in financial assistance expenditures associated with Medicaid expansion and about a 2 percentage point increase in Medicaid shortfall, but this was nonsignificant.

- Assuming an average total expenditure on community benefit of about $20 million, a 4 percent change can be the difference between $200,000 and $1 million.

- A close tradeoff between financial assistance and Medicaid shortfall was observed across hospitals in many different settings (e.g., urban, non-urban, teaching, large, small, high-poverty-rate, low-poverty-rate, etc.). Some hospitals may have increased charges to claim more Medicaid shortfall as their spending on financial assistance decreased. Alternatively, but perhaps less plausible, is that some patients previously covered under private insurance may have enrolled in Medicaid, which would account for an increase in Medicaid shortfall that was higher than expected.

- Findings should be considered in the broader context of how hospitals and communities interact. While many nonprofit hospitals continue to spend comparatively little on community health improvements, they are also actively pursuing patients for unpaid medical bills, reporting debt to credit agencies, suing patients, and garnishing wages.

- In related work, DiGioia found that community characteristics, such as unemployment rates and poverty rates, are associated with a higher likelihood of a hospital reporting patient medical debt to credit agencies. This is not just an issue of whether hospitals are contributing sufficient benefit to warrant their tax exemption or moving their community benefits upstream; it is also an equity issue.

DiGioia concluded that her research indicated that “hospitals may have capitalized on the rise in Medicaid patients to inflate their Medicaid shortfall and maintain the appearance of stable spending on community benefits, while the financial assistance they offer was going down. If the pattern persists, it implies that the Medicaid shortfall needs to be removed from what counts as community benefits.” Alternatively, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) could revise reporting requirements to better capture the information used to calculate the Medicaid shortfall. DiGioia said that this is also an opportunity to consider whether community benefits could be a viable national funding stream for population health improvements and that there may also need to be changes in what constitutes community benefit spending.

Lillie-Blanton next introduced Suma Nair, who began by explaining the mission of the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) Health Center Program, which is to improve the health of the nation’s underserved and vulnerable populations. The program is rooted in community-oriented primary care and over the years the work has

been nurtured and codified in community health centers. HRSA, Nair continued, provides grants to support primary care services, which represent approximately 20 percent of the overall operating budget of any given health center. Nair provided more statistics including that the payer mix at health centers is almost 50 percent Medicaid, 10 percent Medicare, and a range of uninsured patients, there are 1,400 health centers and nearly 14,000 service delivery sites across the United States, serving nearly 29 million people, and approximately 1 in 11 individuals in the United States is served by a health center. Nair said that the populations served are primarily special populations, including those experiencing homelessness, public housing residents, and agricultural workers. About one-quarter of patients are served in a language other than English, and 90 percent or more of patients live at or below 200 percent of the federal poverty line, she said.

Nair further discussed how the health center’s model of care was developed over 50 years ago as a grant-based program and was, by design, rooted in community-oriented primary care. She said that a few core fundamentals to both the model of care and community accountability are mission-critical to advancing population health in underserved communities served by health centers.

Expanding on these fundamentals, Nair said that health centers are located in an area of high need1 (i.e., areas or communities that have health profession shortages or medically underserved communities or populations). While there is a community health center in almost every community, there are a few communities across the country without one or without access to their full range of services. Nair said that HRSA program funding is focused on two key areas: (1) ensuring that a health center exists in every community that needs it, and (2) providing the full range of services to meet needs in a coordinated, integrated way for patients.

Second, Nair said, health centers provide comprehensive, integrated primary care (e.g., medical services, behavioral health, oral health, and enabling services). Enabling services support people in continuing their engagement with health care and care delivery, and include translation, transportation, case management, care coordination, etc. She also said that many health centers provide mental health and substance use disorder services.

Third, Nair explained how health centers collaborate with other community providers to maximize the resources and services provided to the patients to help them improve their health. If a health center does not provide a certain service, Nair said, the center can partner with or

___________________

1 Find a Health Center. https://findahealthcenter.hrsa.gov/ (accessed August 22, 2023).

refer patients to hospitals, specialists, and other social service agencies to ensure the full complement of wraparound services.

Fourth, community health centers have a patient-driven and patient-majority board requirement focused on “health care for the community, by the community,” Nair said. The goal is for 51 percent of health center board members be community members who use health center services. Services are available to all, and fees are adjusted based upon ability to pay.

Fifth, Nair said that the health centers adopt a range of performance, clinical, financial, and administrative requirements to ensure that patients are receiving high-quality and effective care. Regular needs assessments and quality improvement efforts through regular site visits are used to document emergent demographic shifts, population needs, and complementary services and programs and, ultimately, drive the response of health centers. Additionally, she said that regular site visits ensure that all program requirements are in place and supporting broader goals. Finally, Nair said that HRSA ensures there is quality infrastructure in place, regular reporting to the board, and the appropriate interventions to address or close gaps where necessary.

In addition to compliance requirements, Nair continued, community health centers test investments and other strategies that advance community and population-level health. Nair provided an example of HRSA investing in infrastructure and the care delivery model early in the Recovery Act and ACA. In practice, this meant integrating service lines, meeting patients where they were, and taking a proactive, population approach. Health centers support a patient-centered medical home model for care delivery and adopt a variety of tools (e.g., electronic health records, health information technology tools, population health management tools, analytic tools, etc.) that allow care teams and the health centers to use data to support better quality improvement. The broader strategy aligns systems, investments, and technical assistance for partners at the national and state level. This type of approach, Nair said, has led to “tremendous strides” with common benchmarks, data sharing, and transfer of best practices. To support transparency, health center data is shared publicly on the HRSA website,2 including clinical quality measures, patients served, demographic mix, and compliance measures that support population community health improvement. Incentives are also integrated as part of the broader effort of closing health equity gaps, Nair continued, including dollars and resources for health centers that “improve against their own performance if they are among the top 30 percent of all health centers or if they exceed national benchmarks.”

___________________

2 Health Center Program uniform data system (UDS) data overview. https://data.hrsa.gov/tools/data-reporting/program-data (accessed August 22, 2023).

The key focus, Nair said, is now on “accelerating innovation” and developing an evidence base to better support health centers based on what the community needs, including supporting good data and focusing on equity. The community health centers (CHCs), Nair said, are beginning to collect de-identified patient-level data to better understand differences in care and outcomes; this also allows for stratifying data by various patient characteristics (e.g., sexual orientation, gender identity, race and ethnicity, income, insurance, etc.). Nair said that HRSA is focused on directing funding, training, and technical assistance toward health centers to support their progress in these areas.

QUALITIES OF THE HIGHEST-PERFORMING HEALTH CENTERS

High-performing CHCs have four common areas of focus, Nair said. They are:

- A focus on population health and the social determinants of health. They seek to align funding, training, technical assistance efforts, and partnerships to support health centers and advance performance across all domains, maximizing governance, workforce, population health, and patient engagement to improve community health.

- Routine screening for social risk factors. Almost 70 percent of health centers screen patients for health-related social risk factors, with the long-term goal of using that information to shape treatment and care delivery and provide referrals to other agencies.

- Data standardization. CHCs seek to ensure the interoperability of health information technology, standardization of data, and exchange of that data across social and health sectors to support and empower the community.

- Supportive investments. CHCs invest in activities that address social risk factors at the patient and community level, ultimately supporting upstream population health efforts

In closing, Nair identified two existing incentives. One was a prize challenge for health centers partnering with community organizations and others on new ideas that “improve access to health care and health outcomes.” Winning teams implement and scale ideas that move forward without the pressure of a grant. The second was a quality improvement fund focused on innovation. Nair offered virtual care as an example of an opportunity to optimize care for all patients who could benefit from the technology (e.g., farmworkers, individuals experiencing homelessness, patients with limited English proficiency). The next focus of innovation

for health centers, Nair said, will be issues of maternal health, specifically co-designing interventions and taking them to scale.

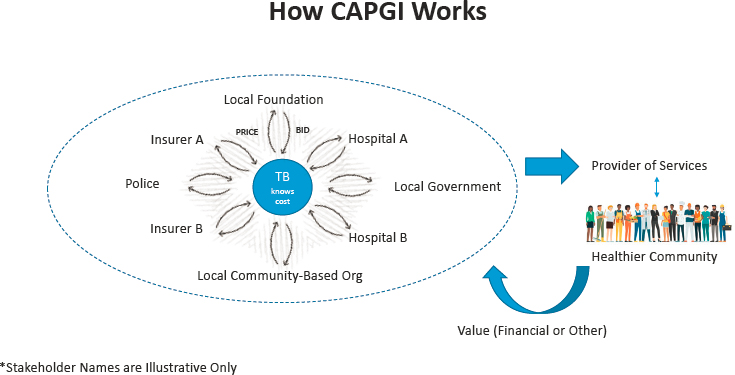

Lauren Taylor, an assistant professor in the Department of Population Health at New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine, provided an overview of Collaborative Approaches to Public Good Investments (CAPGI), a financing model for upstream community investments (Nichols and Taylor, 2018; Nichols et al., 2020). The model was developed in partnership with Len Nichols from the Urban Institute and piloted in 10 U.S. communities. The CAPGI model is one of many tools that can finance upstream social determinants of health investments and can be used along with government tax and spend, philanthropy, and others. In developing CAPGI, the team learned a lot about misplaced assumptions.

Taylor outlined the use cases for the model. CAPGI was designed “to be responsive to the classic free rider problem,” in which a benefit accrues to non-investors, and investors (anyone putting money on the table) may not recoup the value of an investment unless there is collaboration with non-investors. As an example of this problem, Taylor described Medicaid managed care plans, which may benefit from home delivered meals to enrollees but will not want to take a risk on that investment. Taylor said that if one plan invests in an enrollee, and this enrollee switches plans the following year, then the new plan will reap the benefit. This type of scenario, Taylor said, can be an opportunity for a competitor plan.

A different use case, not anticipated in but amenable to using CAPGI, are investments that warrant collaboration due to a better negotiated price. Take the example of child care, Taylor said, in which corporations can hire multiple child care providers in-house but assume a higher cost than building a community child care center. In this scenario, CAPGI offers a governance structure for collaboration across multiple organizations and multiple sectors and also enables price assignment, which is a difficult concept to implement when organizations have different amounts of financial resources that can contribute towards a project.

CAPGI provided a response to these types of problems by introducing four key roles into a negotiation:

- Trusted broker, which could be a backbone organization, foundation, piece of municipal government, or other community broker elected by the community pursuing the project. In Cleveland, the United Way served as the trusted broker on a CAPGI project.

- Stakeholders (or bidders), which are most often health care delivery organizations, hospitals, health systems, managed care plans or other insurers, along with a mix of community-based organizations, local government, and philanthropy.

- Vendors or service delivery organizations. In Cleveland, this was the Benjamin Rose Institute, a community-based organization with a large home-delivery meals program.

- Technical assistance or coaches. Taylor, her colleague, and a team of evaluators at the Altarum Institute led this work, but over time, as the model becomes more common and familiar, the utility of someone playing this role will diminish.

Taylor described what a CAPGI process looks like in action. First, a trusted broker convenes people and starts a discussion about a problem in the community. Once a community group has decided on the type of project, the trusted broker determines the project cost. The stakeholders—for instance, Hospital A and Hospital B, Insurer A and Insurer B—each submit a private bid on the project to the trusted broker. This allows fierce competitors, such as Hospital A and Hospital B or Insurer A and Insurer B, to contribute to the same project, as “their willingness to pay for a given intervention” is not public. The trusted broker sums the bids and identifies whether a “social surplus” exists. A surplus means the sum of the bids exceeds the cost and the project moves forward. If the bids do not meet the value of the project, the stakeholders can re-bid or walk away. If a surplus exists, the trusted broker receives the money from the stakeholders and holds the contract with the provider of services. Ultimately, “the value of that project ostensibly flows back to the individual stakeholders.”

Taylor clarified that on any given CAPGI project, competing groups may pursue joint financing of the same program, service, or structural change. Additionally, local partners (e.g., foundations, communities, organizations, the police, a government) form a CAPGI community coalition. Coalition members generally come together from other pre-existing coalitions, which can provide a strong base of trusting relationships. The reality is that the work takes time, “coalitions are born of voluntary action,” and people may not show up consistently. An overview of the CAPGI process is provided in Box 3-2, and a visual of the process is shown in Figure 3-1.

Taylor outlined the CAPGI process in three phases—Phase 1: coalition formation (or figuring out who needs to be at the table, including some non-financial bidders); Phase 2: launch and deliver services; and Phase 3: monitoring and evaluation. The CAPGI process took about 2 years with “capable leadership,” and while it may be possible to do it faster, Taylor reiterated the importance of time. In Cleveland, as a result of using the CAPGI model, the Benjamin Rose Institute successfully delivered more than 400 home-delivered meals to people who otherwise would not have had access to them.

NOTE: TB = trusted broker.

SOURCE: Taylor presentation, June 22, 2022.

CAPGI projects3 in Cleveland, Ohio, Albany, New York, and Waco, Texas, are examples of pilot projects that are up and running. Cleveland and Albany are in the process of rebidding CAPGI projects. Annapolis, Maryland, and Washington, D.C., are “green communities,” that is, communities that are expected to come online. The Washington, D.C., project is led by the Jane Bancroft Foundation, Taylor said, and has provided a “phenomenal community-engaged and participatory process of designing an intervention and then figuring out how to finance it,” with a focus on “Black women living east of the Anacostia River navigating cancer and economic mobility.” Finally, Taylor continued, “CAPGI is designed with project-specific funding in mind.” The model is strongly oriented toward health investments that “have public good qualities” and allows communities the flexibility to change projects from year to year.

In closing, Taylor reiterated that CAPGI is a voluntary undertaking. While there are protocols in place (e.g., letter of intent, grant guidelines), CAPGI does not guarantee community accountability. Community partners can come together without involving community-based organizations or meaningful community engagement, but this approach tends to slow down the process. The CAPGI project in Washington, D.C., offers an example of a strong group of volunteers coming together with a trusted broker, powerful leadership, and a thoughtful, community-engaged process.

AUDIENCE DISCUSSION

To begin the discussion portion of this panel, Lillie-Blanton asked DiGioia if her research examined Medicaid payment rates during the period in which community benefits were examined and whether those payments account for some of her findings. DiGioia said that she did not see a relationship with the findings, nor did she observe a consistent outlier for higher or lower payers on Medicaid rates.

Given the increasing prevalence of mental health issues, Lillie-Blanton asked Nair what is being done to help federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) strengthen the delivery of behavioral health services and whether FQHCs are discussing behavioral health needs with their communities. In health centers, Nair replied, dollars from the American Rescue Plan Act supported COVID-related activities and the maintenance of service capacity. During the pandemic, she added, there was an uptick in behavioral health services and telehealth as a key service line. This was an opportunity for discovering how to better support and address “unmet

___________________

3 Participating communities: https://capgi.urban.org/index.php/category/participatingcommunities/ (accessed August 22, 2023).

behavioral health needs,” Nair said. She added that, moving forward, this will be a key area of focus for investments, technical assistance, and training.

Next, Lillie-Blanton asked Taylor to explain the role of communities in CAPGI and how the trusted broker and coalitions engage with those who are most affected by health and social inequity. “As an example,” she said, “what if the community decides that the value of a project is worth investment, but the coalition of trusted brokers do not?” Taylor said CAPGI is a voluntary undertaking, and, as such, no formal requirement exists for a given project to be responsive to the communities it affects. Any given community could have more than one CAPGI project or create its own project to respond to a specific need. Taylor and her colleague work with communities to ensure that coalitions thoughtfully consider projects and that trusted brokers “collaborate across organizations for the public good.” Generally, she said, trusted brokers are foundations, community-based organizations, or nonprofits (e.g., United Way). However, there is nothing in the model that prohibits “individual citizens sitting at the table and potentially bidding” as a stakeholder on a project.

Lillie-Blanton followed with a question to DiGioia: Given what she knows about the law, what strategies would she suggest that state and local governments and nonprofit organizations take to drive greater efforts aimed at population health improvement? DiGioia offered suggestions for the IRS, state government, and hospitals. First, the IRS must “revise the definition of community benefit and require more transparent reporting,” and, second, eliminate “the distinction between community health improvement and community-building activities.” Housing for vulnerable populations and environmental improvements are generally considered community building, which means they are not considered community health improvements, a community benefit. Eliminating the distinction would allow hospitals to appropriately classify “population health improvement work” as community benefits. Second, state government should ensure that community benefit spending requirements align with community health needs assessments. Some communities are already doing this, she said, but “there is no current requirement at the federal level” to align spending with community needs. Third, hospitals must collaborate to better meet critical needs and measure population health improvements. Some hospitals in the District of Columbia have already started to do this.

Lillie-Blanton then asked Taylor if, in communities where the CAPGI model is thriving, the development of trust and power sharing has resulted in more engagement in decision making. Although there is evidence that trust is growing, Taylor said, it is hard to imagine hospitals sharing their negotiated rates for all plans. The CAPGI work suggests that

over time, “coalitions will grow more willing to take risks on what kinds of investments they might be willing to make together.”

Population health improvement is clearly in the mission of HRSA and community health centers. Lillie-Blanton asked Nair to talk about how HRSA and community health centers have embraced more upstream efforts to improve population health versus just focusing on the social-related health needs of the populations they currently serve. Health centers have long taken on roles as health care communities, Nair said, even before conversations on the social determinants of health or grant programs emerged. Health centers support a broad range of efforts to improve population health, including addressing food insecurity, housing, and providing educational programs on community gardens and nutrition. While the strength of these partnerships varies, health centers bring together critical partners to support civic engagement and lead work that improves the social determinants of health.